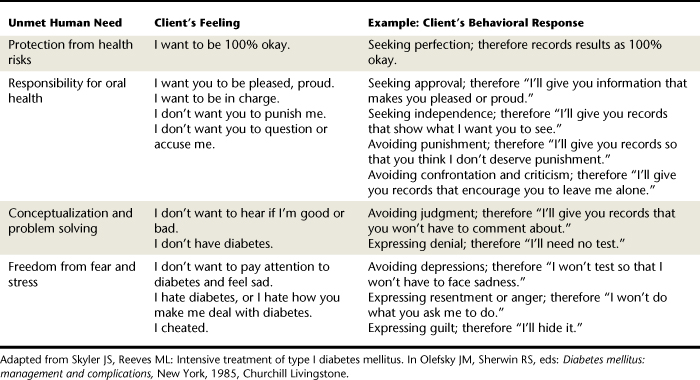

CHAPTER 45 Persons with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection

Treat clients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) using a healthcare team approach.

Treat clients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) using a healthcare team approach.The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and is one of the largest public health challenges facing the world. HIV/AIDS cause gradual impairment of the host immune system so that the disease is accompanied by other chronic health problems. Knowledge of the continuum of immunodeficiency—from infection with HIV on one end to debilitating disease from AIDS on the other—has heightened public awareness of and concern for individuals with HIV/AIDS. Although still not curable, HIV infection and AIDS are now treatable, chronic medical conditions owing to the many scientific advances in understanding the virus since it was first identified in 1983.

The dental hygienist must be aware of conditions commonly accompanying HIV/AIDS, knowledgeable about client care, and comfortable treating clients with HIV/AIDS. Although the knowledge base regarding HIV/AIDS is vast, it is far from complete. The HIV/AIDS epidemic serves as a potent reminder that infectious diseases have not been conquered and that epidemics are not events of the past.

BEGINNINGS OF THE EPIDEMIC

Immunosuppression is the decreased ability of the body to mount natural immune defenses to disease-causing agents. Unusual opportunistic infections, such as illnesses associated with severe immunosuppression, were first identified in several young, previously healthy homosexual males who were found to have a rare and aggressive pneumonia usually associated only with severe immunodeficiency. These first documented cases of AIDS in the United States were reported in June 1981 by the Centers for Disease Control, but the disease was not given a name until considerably later. HIV was identified and associated with these unusual conditions in 1983. Subsequently, multiple cases of oral Kaposi’s sarcoma were identified in the homosexual population. Previously Kaposi’s sarcoma, a rare cancer of blood vessels characterized by dark red or purple papular lesions, had been found only in elderly men of Mediterranean heritage, and then only on the legs.

After these peculiar epidemiologic findings, several deaths in the United States and abroad in the 1970s were suspected of being caused by the same agent. In a retrospective analysis, frozen serum samples from those cases revealed the presence of HIV antibodies. In the early 1980s, similar occurrences of immunodeficiency-related deaths, which would later be identified as early AIDS cases, were also reported in Haiti, in several countries in Africa, and in populations requiring routine blood transfusions (e.g., hemophiliacs).

Although the disease was first recognized among men who have sex with men, from the early days, HIV/AIDS have also been observed in heterosexual populations, especially in Africa where the epidemic is particularly severe. Today, HIV infection has become a worldwide epidemic. Globally, 33.2 million people are estimated∗ to be infected; most of them live in sub-Saharan Africa.1

HIV includes two closely related viruses, HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is the more common of the two viruses and is predominant in most of the world, including the United States. HIV-2 is primarily found in West Africa and is more closely related to the simian immunodeficiency virus isolated from sooty mangabey monkeys (SIVsm). HIV-1 is known to have at least nine subtypes, or clades, identified on the basis of genetic sequencing.2

PATHOGENESIS OF HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS

The HIV virion, or virus particle, is composed of a core of ribonucleic acid (RNA) encapsulated with a lipid coating. A serologic marker on the coating binds to receptor sites on CD4+ T lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell that is important for cell-mediated immunity. CD4+ T lymphocytes do not have cytotoxicity, or the ability to kill a cell, but they do play an important role in activating cytotoxic T lymphocytes. The virus infects by fusing with the cell membrane of the CD4+ T lymphocyte and entering the cell, where it releases its RNA. HIV is called a retrovirus because once within the cell it uses the enzyme reverse transcriptase to convert viral RNA into deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). This process is the “reverse” of what typically occurs in animal cells (i.e., the conversion of DNA into RNA).

After the viral RNA is released into the host cell and is changed into DNA, it can integrate into the host cell’s genome. This effectively allows HIV to “highjack” the host cell so that it produces more HIV viruses. When activated, the infected cell will synthesize viral protein, create more HIV virions, and kill the host immune cell. The HIV particles produced can then circulate and infect other cells of the immune system.3 The resultant destruction of immune cells, including CD4+ T lymphocytes and macrophages, weakens the host immune system. The characteristic immunodeficiency occurs when the virus suppresses the immune response, the body’s natural defenses against invasion by an organism.

Left untreated, the HIV infection leads to a gradually diminishing immune response due to depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes. The weakened immune response makes the host susceptible to opportunistic infections and malignancies.3 This explanation of the disease process is a very simple description of a complex immunologic reaction and is intended to present the general idea of how the virus replicates itself in the human body. For further information, refer to the Suggested Readings section on the  website.

website.

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS EXPOSURE AND INFECTION

HIV is transmitted through contact with semen, vaginal secretions, breast milk, and infected blood or platelets. Sexual contact is the primary source of infection among men who have sex with men, whereas intravenous drug users are at high risk owing to sharing blood-contaminated needles. HIV-positive mothers may transmit the virus to the fetus during pregnancy, at birth, or when breast-feeding the infant.

Acute Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection

Acute HIV infection syndrome occurs 6 to 56 days after exposure. Manifestations of initial infection vary but include some or all of the following signs and symptoms:

There is considerable variation in presentation of acute HIV infection, but it is reported that most persons who are undergoing seroconversion, the acquisition of the antibodies in the blood serum, are ill enough to seek medical attention. Acute HIV infection is also characterized by primary viremia, or the initial spike in viral levels in the bloodstream. Oral manifestations can include erythematous (red) round patches on the hard and soft palate, angular cheilitis, exudative tonsillitis, hairy leukoplakia on the lateral borders of the tongue, and oral ulcers that look similar to aphthous ulcers but may appear anywhere in the mouth or on the lips.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Latency and Immune Status

When primary viremia is suppressed by the body’s initial immune response, an asymptomatic period follows that may last for a variable period of time ranging from months to years. Even though symptoms are not present during this latency period, the virus is present and replicating. This asymptomatic period has been reported to lead to the loss of approximately 10% of CD4+ T lymphocytes per year in infected individuals.3

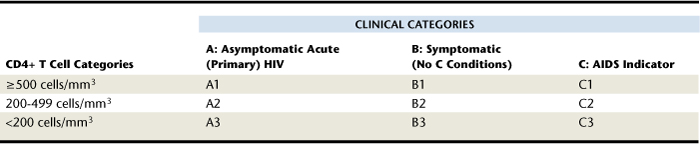

Depending on the health status of the human host, HIV infection can remain latent for several years. Only when certain conditions or clinical indicators called AIDS-defining illnesses become apparent is the HIV-infected individual classified as having AIDS. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classifies HIV-infected persons according to their immune status. The current system includes categories for asymptomatic infection, symptomatic infection, and AIDS indicator conditions.4 The classification system and case definitions are presented in Table 45-1, and the AIDS-defining conditions are listed in Table 45-2. The CDC also performs annual surveillance studies to document prevalence of HIV/AIDS in the United States based on these classification criteria.

TABLE 45-1 Classification System by Clinical Categories (A to C) and Levels of CD4+ T Cells for HIV Infection and AIDS in Adults4

TABLE 45-2 AIDS-Defining Conditions and Diagnostic Criteria4

| Condition | Signs and Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Candidiasis | Of the bronchi, trachea, lungs or esophagus |

| Cervical cancer | Invasive |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Disseminated or extrapulmonary |

| Cryptococcosis | Extrapulmonary |

| Cryptosporidiosis | Chronic intestinal (>1 month duration) |

| Cytomegalovirus disease | Other than liver, spleen, or nodes |

| Cytomegalovirus retinitis | With loss of vision |

| Encephalopathy | HIV-related |

| Herpes simplex | Chronic ulcer(s) (>1 month duration), or bronchitis, pneumonitis, or esophagitis |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated or extrapulmonary |

| Isosporiasis | Chronic intestinal (>1 month duration) |

| Kaposi’s sarcoma | Intraoral or extraoral |

| Lymphoma | |

| Mycobacterium avium complex or Mycobacterium kansasii | Disseminated or extrapulmonary |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Any site (pulmonary or extrapulmonary) |

| Pneumocystis carinii | Pneumonia |

| Pneumonia | Recurrent |

| Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy | — |

| Salmonella septicemia | Recurrent |

| Toxoplasmosis | Of brain |

| Wasting syndrome | HIV-related |

Women with HIV infection or AIDS may have gynecologic manifestations such as vaginal yeast infections, cervical lesions, and cervical cancer. However, there is no general agreement that other HIV-associated conditions behave the same in males and in females. Drug protocols have been studied much more extensively in men, so modification in those protocols when applied to women may become part of treatment in the future.

DRUG THERAPY

The first drugs used to control HIV infection were developed in the 1980s. These drugs targeted the reverse transcriptase enzyme that facilitates virus replication in the cells. They inhibited viral replication but were given in monotherapy, or treatment with just one drug. Monotherapy resulted in resistance mutations and eventually made the drugs ineffective at suppressing viral replication. In the 1990s other drugs were identified that targeted the enzyme in a variety of ways at different stages of retrovirus development. These have been found to be effective and have led to the use of multiple drugs, or the so-called “HIV cocktails,” by HIV-infected individuals. Treatment with at least three drugs, known as highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), is now considered the standard of care.

The process for determining the correct dosages of multiple drugs is extremely complex. It requires constant monitoring, clinical testing, and evaluation by the physician. The potent antiretroviral drug cocktails can have potentially serious adverse effects ranging from headache and nausea to lactic acidosis, severe skin reactions, lipid abnormalities, and organ failure. As one physician specializing in treating HIV cases reported, “Drug combining can be a real challenge. We know that combinations are much more effective than any one drug because they keep the virus from mutating or becoming drug resistant.” When administered and monitored properly, the correct combination will interact beneficially to control the infection, prevent the development of drug resistance, and prolong the lives of HIV-infected individuals.5

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS INFECTION AND ACQUIRED IMMUNODEFICIENCY SYNDROME

In the United States, only 33 states have complete, confidential, name-based HIV infection reporting data. The CDC estimated that in 2006, the total number of people living with HIV/AIDS in these 33 states was approximately 492,000.6 Precise estimates of HIV infection rates are not known because the incidence of new infection is difficult to track. However, the CDC estimated that the rate of diagnosis for adults, adolescents, and children in 2006 in the 33 reporting states was 19 new cases per 100,000 in the population. Overall the infection rate has decreased since 1997, but the absolute number of cases, or prevalence, continues to increase.6

Although women make up a minority of cases, the proportion of women contributing to the total population with HIV/AIDS is increasing steadily. Women accounted for 7% of adult and adolescent cases in 1987, but this increased to 18% by 1994, 23% by 1998, and 27% by 2005. Whereas men are more likely to contract HIV via homosexual contact, women are more likely to do so via heterosexual contact. It is believed that 61% of HIV-positive males contracted HIV through male-to-male sexual contact. In addition, most cases of HIV/AIDS were in individuals between 40 and 44 years of age, whereas persons aged 35 to 39 had the most new HIV diagnoses.7

Racial and ethnic minorities make up a disproportionately large percentage of the population of people living with HIV/AIDS. The demographic trends in 2005 surveillance data (Table 45-3) show that HIV was disproportionately common in black and Hispanic groups. In 2005, 47% of people living with HIV/AIDS were black, 34% white, 17% Hispanic, and less than 1% each were American Indian/Alaska Native or Asian/Pacific Islander.7 Current data are available online regarding the prevalence of HIV/AIDS cases among high-risk groups and are updated regularly. Table 45-4 summarizes HIV/AIDS cases in adults as of 2006 by gender and transmission category.

TABLE 45-3 Estimated Persons with HIV/AIDS, by Race or Ethnicity, and Sex, 2005—33 States with Confidential Name-Based HIV Infection Reporting (Revised June 2007)7

TABLE 45-4 Estimated Numbers and Proportions of Adults and Adolescents Living with HIV/AIDS through 2006 by Gender and Transmission Category (33 States Reporting)

| Exposure Category | Total Cases | Percent of Group Total |

|---|---|---|

| Males (Adults and Adolescents) | 353,825 | 100 |

| Homosexual contact | 218,676 | 62 |

| Injection drug use | 59,077 | 17 |

| Homosexual contact and injection drug use | 25,085 | 7 |

| High-risk heterosexual contact | 47,562 | 13 |

| Other∗ | 3,424 | 1 |

| Females (Adults and Adolescents) | 131,195 | 100 |

| Injection drug use | 33,470 | 26 |

| High-risk heterosexual contact | 95,403 | 73 |

| Other∗ | 2,321 | 2 |

| Children (Cumulative Data through 2006) | 6,703 | 100 |

| Perinatal | 6,143 | 92 |

| Other | 560 | 8 |

∗ Includes hemophilia, blood transfusion, perinatal exposure, and risk factor not reported or identified.

From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: HIV/AIDS surveillance report. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/2006report/pdf/2006SurveillanceReport.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2008.

RISK OF HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS INFECTION AMONG HEALTHCARE WORKERS

Healthcare workers are at risk for occupational exposure to HIV infection, as well as the viruses hepatitis B and hepatitis C, owing to their work-related contact with contaminated blood and bodily fluids. Each year approximately 500,000 healthcare workers experience a percutaneous blood exposure, an exposure to contaminated blood through a needle stick or cut from another sharp instrument. Because accidents can and do occur, it is important for the dental hygienist to understand the relative risk of contracting HIV from an occupational exposure.

The CDC reports that as of 2006 there were 57 confirmed and 140 unconfirmed seroconversions resulting from occupational HIV exposure. All documented transmissions were related to blood, visibly bloody fluids, or concentrated laboratory preparations. Needle penetrations accounted for 86% of the transmissions. None of the transmissions were to dentists or dental workers. Prospective studies of healthcare workers have estimated the risk of acquiring HIV infection from occupational exposure to be approximately 0.3%. In other words, the vast majority of exposures do not result in HIV infection.8 The risk of transmission by other routes such as exposure through the eye, nose, or mouth is even lower at approximately 0.1%.9 Table 45-5 lists the occupations and corresponding numbers of confirmed and possible HIV exposures.10

TABLE 45-5 Healthcare Personnel∗ with Documented and Possible Occupationally Acquired AIDS/HIV Infection, by Occupation, 1981-200610

| Occupation | Documented | Possible |

|---|---|---|

| Nurse | 24 | 35 |

| Laboratory worker, clinical | 16 | 17 |

| Physician, nonsurgical | 6 | 12 |

| Laboratory technician, nonclinical | 3 | — |

| Housekeeper or maintenance worker | 2 | 13 |

| Technician, surgical | 2 | 2 |

| Embalmer or morgue technician | 1 | 2 |

| Health aide or attendant | 1 | 15 |

| Respiratory therapist | 1 | 2 |

| Technician, dialysis | 1 | 3 |

| Dental worker, including dentist | — | 6 |

| Emergency medical technician or paramedic | — | 12 |

| Physician, surgical | — | 6 |

| Other technician or therapist | — | 9 |

| Other healthcare occupation | — | 6 |

| Total | 57 | 140 |

∗ Healthcare personnel are defined as those persons, including students and trainees, who have worked in a healthcare, clinical, or HIV laboratory setting at any time since 1978. See MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 41:823, 1992.

In 2001 a study of dental hygiene student exposure to blood and body fluids surveyed 143 (67%) of 214 U.S. dental hygiene programs. A total of 687 student exposures were reported between 1996 and 1998, involving more than 18,600 students. Most exposures (499) occurred in the second year of training. About 80% of exposures were instrument punctures; 12% were needle sticks among first-year students and 19% among second-year students. Nine contaminated splashes and two bites were also reported.11 These data emphasize the need for caution and inclusive application of prevention protocols.

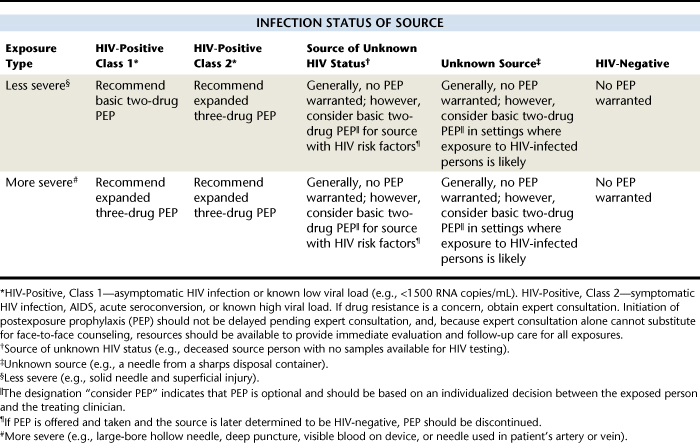

Although risk of contracting the HIV virus from an infected client is less than 1%, dental hygienists must follow best practices for infection control to minimize risk of percutaneous exposure, particularly by needle sticks. Using adequate sterilization and barrier infection control procedures (see Chapter 7) provides a sense of confidence and peace of mind. It is also important to have an action plan in the event that an occupational exposure does occur. This plan should include identification and testing of the source individual for blood-borne diseases, proper reporting of the exposure incident to the CDC, and initiation of a postexposure antiviral drug regimen if indicated. Table 45-6 shows the indications for HIV postexposure prophylaxis in the case of percutaneous exposures, reproduced from the CDC.12

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS INFECTION AND ITS RELATION TO PERIODONTAL STATUS

Previously it was thought that periodontal diseases were more severe in immunocompromised individuals; however, a Tanzanian study comparing the periodontal disease progression of both HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients revealed no significant differences between bleeding on probing, pocket formation, or attachment loss related to HIV status.13 Likewise, studies of HIV-positive men and women in Western countries indicate that attachment loss was similar for both HIV-positive and HIV-negative groups, and bone loss measured radiographically over time has been shown to be unaffected by HIV status.14,15 These data suggest that HIV is not a risk factor for the progression of periodontal diseases. However, for more complete assessment of this association, large-scale population studies remain to be completed.

ORAL MANIFESTATIONS ASSOCIATED WITH HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS AND ACQUIRED IMMUNODEFICIENCY SYNDROME

The oral manifestations of HIV/AIDS-related immunosuppression are amazingly complex. Considerable investigation has been conducted on the oral lesions associated with HIV infection because of their high incidence in HIV-infected individuals. It is important to recognize HIV-associated oral lesions because they are often among the first signs manifested by the HIV-positive individual.

Oral Candidiasis

The genus Candida is a fungus found in normal oral flora; however, it can proliferate in immunocompromised, malnourished, or debilitated persons. Candidiasis, the disease caused by Candida, is the most common HIV-associated oral lesion. Pseudomembranous candidiasis, atrophic or erythematous candidiasis, hyperplastic candidiasis, and angular cheilitis are common oral lesions in HIV-positive persons caused by the strain Candida albicans. Candidiasis is by no means unique to the HIV-infected population, nor is its presence necessarily indicative of HIV/AIDS.

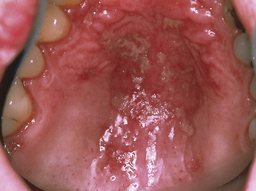

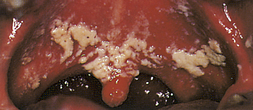

Pseudomembranous candidiasis (thrush) (Figure 45-1) appears as soft, yellow-white curdlike plaques on the oral tissues that when wiped away leave red, tender, and bleeding patches of mucosa. These plaques occur most frequently on the hard and soft palate and labial and buccal mucosa and contain desquamated epithelial cells, fibrin, and the fungus.

Pseudomembranous candidiasis (thrush) (Figure 45-1) appears as soft, yellow-white curdlike plaques on the oral tissues that when wiped away leave red, tender, and bleeding patches of mucosa. These plaques occur most frequently on the hard and soft palate and labial and buccal mucosa and contain desquamated epithelial cells, fibrin, and the fungus. Erythematous or atrophic candidiasis (Figure 45-2) manifests as smooth, red denuded patches on the tongue; red patches on the buccal or palatal mucosa; or desquamative gingivitis. These conditions usually result from the persistence of pseudomembranous candidiasis and loss of the pseudomembrane and are less obvious and more easily missed than white patches.

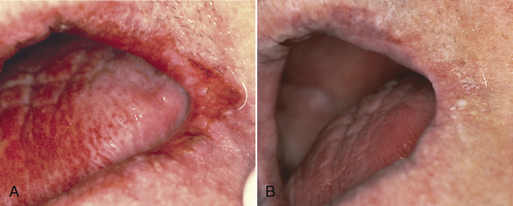

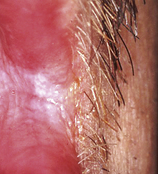

Erythematous or atrophic candidiasis (Figure 45-2) manifests as smooth, red denuded patches on the tongue; red patches on the buccal or palatal mucosa; or desquamative gingivitis. These conditions usually result from the persistence of pseudomembranous candidiasis and loss of the pseudomembrane and are less obvious and more easily missed than white patches. Hyperplastic candidiasis (Figure 45-3) manifests as speckled, homogeneous white lesions that appear on the lateral borders of the tongue or buccal mucosa and may be associated with oral leukoplakia.

Hyperplastic candidiasis (Figure 45-3) manifests as speckled, homogeneous white lesions that appear on the lateral borders of the tongue or buccal mucosa and may be associated with oral leukoplakia. Angular cheilitis appears as redness, cracks, crusting, or fissures at the commissures of the lips (Figure 45-4).The lesions are moderately painful, fissured, and eroded. Medical treatment of angular cheilitis resulting from Candida infection involves a variety of topical or systemic antifungal drugs.

Angular cheilitis appears as redness, cracks, crusting, or fissures at the commissures of the lips (Figure 45-4).The lesions are moderately painful, fissured, and eroded. Medical treatment of angular cheilitis resulting from Candida infection involves a variety of topical or systemic antifungal drugs.

Figure 45-1 Pseudomembranous candidiasis in an individual with AIDS, manifested as white-yellow curdlike plaques on the palate.

(Courtesy Dr. James R. Winkler, Marquette University, Minneapolis, Minnesota.)

Figure 45-3 Hyperplastic candidiasis at the corner of the mouth. Lesion has persisted despite use of systemic antifungal drugs.

Topical applications of nystatin or clotrimazole are commonly used to treat Candida infections. Usually, immunocompromised patients require systemic administration of amphotericin B, ketoconazole, fluconazole, or itraconazole. Please refer to a current dental drug manual for further information about how these drugs are prescribed.

Hairy Leukoplakia

Oral hairy leukoplakia (OHL) is a collection of thick, asymptomatic white lesions associated with the Epstein-Barr virus and usually seen on the lateral borders of the tongue (Figure 45-5). The lesions can be unilateral or bilateral, with long, fingerlike projections, or may have a corrugated appearance. OHL is found almost exclusively in persons with HIV/AIDS. Prevalence is approximately 20% in HIV-infected persons and up to 80% in those with AIDS.

Figure 45-5 Oral hairy leukoplakia of tongue before initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).

Treatment for OHL is usually not indicated, but the lesions respond to HAART. Accurate diagnosis of the lesion is imperative owing to its very high association with HIV infection. OHL is predictive of AIDS, with as many as 80% of individuals with a confirmed diagnosis progressing to the diagnosis of AIDS within 31 months.

Kaposi’s Sarcoma

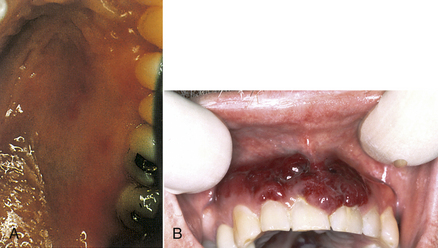

Kaposi’s sarcoma is a malignant, slow-growing, endothelial cell neoplasm seen in some persons with AIDS. It has several associated causative factors, including genetic predisposition, viral infection, environmental influences, and alterations in the immune system, and is particularly related to a newly discovered herpesvirus, Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV). Typically, Kaposi’s sarcoma appears as painless brownish-red nodules primarily on the skin of the extremities, but it can often occur intraorally. Approximately half of AIDS patients with Kaposi’s sarcoma develop oral lesions. The lesions may appear anywhere in the oral cavity and may be small, rather innocuous-looking, flat, reddish-blue or purple-brown lesions of varying size, including large nodular lesions (Figure 45-6).

Figure 45-6 A, Oral Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions on the palate of an individual with AIDS. B, Oral Kaposi’s sarcoma on the gingiva.

(A, Courtesy Dr. James R. Winkler, Marquette University, Minneapolis, Minnesota.)

Oral Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions often appear on the gingiva associated with the teeth. In these cases the tumors may be significantly enlarged by the presence of oral biofilm and calculus. Kaposi’s lesions on the gingiva associated with the teeth require excision or systemic therapy, as do Kaposi’s sarcomas located away from the teeth. Localized Kaposi’s lesions tend to diminish in size and are treated through surgical excision, laser excision, antiretroviral agents, cryotherapy, low-dose radiation treatment, intralesional injection with vinblastine, interferon-α, sclerosing agents, or antitumor chemotherapy.

Dental hygienists and dentists are sometimes hesitant to treat the gingival condition for fear of harming the Kaposi’s lesions or causing significant bleeding. However, periodontal care must be provided, and in some cases tumor reduction is achieved by nonsurgical periodontal care. Oral biofilm removal, scaling, and root planing are essential to maximizing the effects of periodontal therapy and may help reduce the size of the tumor before tumor-specific therapy.

Lesions of the Periodontium

Aggressive periodontitis has been reported in patients with HIV/AIDS, for example, necrotizing ulcerative periodontal diseases. Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG), a bacterial infection of the gingiva characterized by inflammation, bleeding, pain, fever, and halitosis (Figure 45-7), is a form of gingivitis not specific to HIV/AIDS. Its treatment will be the same as in HIV-negative patients, that is, cleaning and debriding the sensitive areas with cotton or gauze soaked in H2O2 and a topical anesthetic agent daily or every other day for about 1 week, twice-daily rinses for 30 seconds with 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate mouth rinse, introduction of meticulous oral biofilm control as soon as the client can tolerate it, then definitive scaling and root planing once the client has had some improvement in disease symptoms and healing. Initially the dentist may prescribe a systemic antibiotic and prophylactic antifungal medication in the presence of lymphadenopathy, systemic symptoms, and moderate to severe oral tissue destruction. The client should be advised to avoid alcohol and tobacco products and to eat a nutritious diet. Note that H2O2 mouth rinses are contraindicated in immunocompromised individuals. It is important to note that NUG appears without evidence of attachment loss.

NUG in the presence of rapid attachment and interproximal bone loss, no matter how extensive, is more properly diagnosed as necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis (NUP) (Figure 45-8). NUP is very painful, and sequestrum can occur. Extreme cases of exposed bone and sloughing tissue are sometimes referred to as necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis, a condition known as cancrum oris (noma) that is found in some underdeveloped countries. Treatment is similar to that for NUG. The dentist may need to remove affected bone for healing to occur (see discussion of treatment of NUP later in this chapter).

Figure 45-8 Necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis in an individual with AIDS showing color change, necrosis, and sloughing of the periodontal tissues.

(Courtesy Dr. James R. Winkler, Marquette University, Minneapolis, Minnesota.)

On examination of the periodontium of a client with HIV/AIDS, the gingiva may appear very red. This fiery-red soft tissue may sometimes appear as a line, either localized or generalized, along the gingival margin, called linear gingival erythema (LGE) (see Figure 45-7). The gingival changes that extend partly toward or directly onto the alveolar mucosa may have the more typical appearance of necrotizing ulcerative disease. In addition, the alveolar mucosa also may be bright red or have red petechia-like patches.

Subgingival oral biofilm of HIV-positive persons has been shown to harbor high proportions of the same periodontal pathogens found in HIV-negative persons with periodontal lesions along with Candida and herpesviruses. More subgingival yeasts have been identified in HIV-positive adults with periodontal disease than in HIV-negative people with periodontal disease.16 C. albicans may play a causative role in these exaggerated cases of gingival and periodontal diseases. These cases are typically unresponsive to simple mechanical removal of oral biofilm and calculus. Additional chemotherapeutic agents are often required to control the pathogens that cause the infection.

The precise mechanisms of the severe form of periodontal destruction sometimes seen in HIV-positive individuals are not clearly understood. The relationship among presence of increased amounts of Candida, herpesviruses, xerostomia, altered lymphocyte action, and potentially poor nutrition remains to be studied in this extremely destructive periodontal disease process. The client may have gingivitis extending into the alveolar mucosa, NUG, or NUP with exposed bone. Achieving successful clinical oral outcomes requires consultation with the dentist and physician.

Lymphadenopathy

Lymphadenopathy, or swollen lymph nodes, is a sign that frequently accompanies a range of human illnesses. Cervical lymphadenopathy, a disease affecting the lymph nodes of the neck and most often recognized by swelling, is commonly identified in HIV-positive persons. It is almost always present during the acute phase of HIV infection and is found frequently at later disease stages.

Oral Warts

Human papillomavirus is commonly found in HIV-infected individuals. This virus has many subtypes, one of which is associated with the formation of oral warts (Figure 45-9). Although oral warts can occur in any individual regardless of HIV status, recurrence after treatment is uncommon except in the case of HIV-infected individuals. HIV-associated oral warts can be large and multifocal and present aesthetic and functional problems. In HIV-positive individuals receiving antiretroviral therapy, an increase in oral warts and a decrease in OHL and oral candidiasis have been reported.

Recurrent Herpes Simplex Virus Infection

Most individuals have been exposed to primary herpetic infections, either clinical or subclinical in nature, at some time during their lives. Recurrent herpes simplex virus infection can occur in up to 40% of the HIV-positive population and is the usual manifestation of herpesvirus infection in individuals who are HIV-positive or have AIDS. Recurrence of herpes appears to be related to the breakdown in local immune activity or alterations in local inflammatory mediators that allow the herpesvirus to become active again. In general, recurrent herpetic lesions heal within 1 to 2 weeks and are not related to secondary infections. However, when they occur in the HIV-infected population they can be more severe and persistent. Herpetic lesions can also become secondarily infected with bacteria or fungi. The pain associated with herpes lesions can significantly restrict the HIV-positive individual’s intake of food, thus compromising adequate nutrition.

Less-Common Lesions

A variety of infections, neoplasms, and other oral lesions have been described in HIV-positive clients. Although rare, they should be recognized and treated. The dental hygienist plays a role in performing oral evaluations and informing clients of the presence of lesions so that referral for diagnosis and treatment may be encouraged. It is always important to be attentive to changes in health and to encourage clients to seek additional care immediately.

THE DENTAL HYGIENE PROCESS OF CARE IN HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS–INFECTED PATIENTS

The dental hygienist should be sensitive to the many challenges faced by HIV-positive clients. HIV-positive patients are commonly on complex, demanding drug regimens to control the disease process. They may be struggling to live with HIV while striving to maintain a healthy lifestyle. In addition to the medical challenges, people living with HIV/AIDS also encounter social stigma. The HIV-positive client may have been previously shunned and may fear the same when visiting the dental hygienist. This may cause the HIV-positive client to be reluctant or fearful of the clinician’s response to knowledge of his or her HIV infection, even though the client may be eager, cooperative, and happy to comply with recommendations for professional care. One effective way to initiate a professional relationship and restore a sense of safety to both client and dental hygienist is to shake hands on introduction. The courtesy of this polite touch infuses the professional relationship with confidence and defuses unwarranted fear and alienation.

Assessment

During the assessment phase of care the dental hygienist must be particularly sensitive to clues from the client’s health history, pharmacologic history, and observations of clinical conditions associated with HIV infection. Specific questions on the health assessment form should address the following:

The dental hygienist discusses these issues frankly and considers the client’s answers in a nonjudgmental way to stimulate dialogue. When clients indicate that they have been tested for HIV, the dental hygienist should explicitly ask if they are HIV-positive or HIV-negative. If HIV infection is revealed, the dental hygienist should assess the client’s support systems such as family and partners. While validating the health history and during the interview, the client may report recent hospital stays for conditions associated with HIV status, as listed in Table 45-2. The client may also report high-risk sexual behavior and/or intravenous drug use. Throughout assessment it is imperative to build trust with the client by reaffirming professional confidentiality and by showing a supportive attitude.

Medications that an HIV-positive person might be taking include combinations of the following antiviral drugs:

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) such as abacavir (ABC), zidovudine (AZT), or lamivudine (3TC)

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) such as abacavir (ABC), zidovudine (AZT), or lamivudine (3TC) Nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) such as efavirenz (Sustiva or Stocrin) or nevirapine (Viramune)

Nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) such as efavirenz (Sustiva or Stocrin) or nevirapine (Viramune)Extraoral assessment may reveal purplish-red nodules on the skin indicative of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Intraorally conditions may include the signs and symptoms associated with candidiasis, OHL, Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions, or necrotizing forms of periodontal disease. There might also be unusual lesions; such clients should always be referred to a dentist or physician for evaluation.

Dental Hygiene Diagnosis

Several of the human needs described in Chapter 2 are relevant to care for the HIV-infected individual. For example, clients may be extremely anxious about having acquired HIV. The dental hygienist can help alleviate this anxiety by pointing out that treatments have advanced greatly. Educating clients about how HIV infection affects the oral structures and how to prevent or lessen the severity of these oral problems may empower the patient to feel some control over the disease. This feeling of empowerment enhances the client’s sense of freedom from fear and stress. Dental hygiene care for HIV-infected individuals encourages clients to take responsibility for oral health and to understand oral and systemic health-related issues.

Planning Dental Hygiene Care

The dental hygiene care plan must include client education, therapeutic scaling and root planing, oral biofilm control, provision of posttreatment instructions, evaluation of care, and frequent continued care. Dental hygiene care must be integrated with the overall dental treatment plan in consultation with the physician. For example, prescription medication for oral candidiasis, oral biofilm control, or gingival inflammation may be needed. In addition, the oral healthcare team may want to obtain the client’s most recent blood test results from the physician. Clients’ platelet counts, prothrombin times, and partial prothrombin times are sometimes used to predict excessive postoperative bleeding before nonsurgical or surgical periodontal care is provided.

In the case of more severe forms of NUG and NUP and of oral lesions such as those of Kaposi’s sarcoma, dental hygiene care must always be in collaboration with the dentist and physician. Sometimes, as in the case of NUP, the need for surgical treatment is so urgent that periodontal surgical intervention may be done at the same appointment as the dental hygiene care.

HIV-positive persons can be very health-conscious and embrace preventive procedures such as brushing, interdental cleaning, and daily mouth rinsing with an effective antimicrobial agent. This focus on self-care can be a great advantage for the dental hygienist in designing and implementing a preventive program. The dental hygienist needs to evaluate the client’s knowledge of oral biofilm and oral disease processes as well as the person’s dexterity level before selecting strategies that lead the client to optimal oral health. Should deficits in skin and mucous membrane integrity be identified, this interest in prevention can be an asset in motivating the client to improve oral self-care. An over-the-counter American Dental Association (ADA)–accepted antibacterial mouth rinse or a prescribed 0.12% chlorhexidine mouth rinse may be recommended to assist in the control of supragingival bacterial plaque and gingivitis. Nutritional counseling may also be helpful to encourage a diet conducive to healing and oral maintenance. The client also may be consulting or may need to consult a nutritionist, and therefore the dental hygienist may be sharing responsibility with this member of the healthcare team.

Implementation

Once formulated, the plan of care is implemented according to the goals and priorities established by the client and the oral healthcare team.

Infection Control

Some HIV-infected individuals do not reveal their status to healthcare workers. This lack of disclosure may be either because the patient has privacy concerns or because the patient is yet unaware of the diagnosis. Standard precautions for infection control are essential for all clients and can be relied on to protect the dental hygienist and other members of the dental team.

Scaling and Root Planing

Some opinions suggest that scaling and root planing should be performed on HIV-positive patients using only hand-activated instruments because power scaling devices generate an aerosol. To date, there have been no documented cases of HIV infection through an aerosol exposure, so this proposed mechanism of aerosol transmission is not supported by the research evidence. In fact, the dental hygienist may prefer to perform therapeutic scaling and root planing procedures using ultrasonic instrumentation because there is generally less treatment time and because the procedures can often be performed without using injected local anesthetic agents, thereby reducing the possibility of needle punctures.

Generally, clients with HIV/AIDS present with typical oral needs. They can have gingivitis, periodontitis, xerostomia, dental carries, etc., and they can also have healthy, well-maintained oral conditions. They require meticulous oral biofilm control and periodontal debridement and are maintained at regular intervals of 2 to 3 months.

Treatment of Necrotizing Ulcerative Periodontitis

Treatment of NUP consists of the aggressive control of the microbial challenge and local irritants. In addition, periodontal surgery may be required to remove necrosed tissues, including bone. Local irrigation of the gingiva and affected tissues with 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate or povidone-iodine (Betadine) has also been recommended. Disposable syringes with blunt needles or cotton swabs are required to adequately flush the affected tissues. Persons treated for NUP require frequent monitoring and evaluation. Postoperative care requires good mechanical oral biofilm control and twice-daily 0.12% chlorhexidine rinses for chemical oral biofilm control throughout the mouth. Clients must be informed of possible side effects of chlorhexidine, including staining of the teeth, discoloration of the oral mucosa, calculus accumulation, and altered taste sensation. Antibiotics such as metronidazole to control oral anaerobic pathogens must be used with caution and in consultation with the treatment team. HIV-positive clients may experience overgrowth of other opportunistic organisms when some bacteria are suppressed, including Candida. The sequence of procedures for treating NUP in an HIV-positive client is presented in Procedure 45-1.

Procedure 45-1 DENTAL HYGIENE CARE FOR THE HIV-INFECTED CLIENT

STEPS

Client with Unexpectedly Severe Periodontal Signs and Symptoms and/or Oral Lesions

Evaluation

After comprehensive dental hygiene care has been completed, the dental hygienist should evaluate the client to ensure that the established goals have been met. Evaluation should take place at the expected intervals. In the case of initial therapy (phase I therapy) reevaluation should occur in about 4 weeks. This allows time for healing of the connective tissue so that the client can be probed and assessed accurately. Continued-care intervals should be 2 to 3 months. Frequent care intervals provide opportunities to assess the client’s oral health, self-care practices, and nutrition for a good long-term outcome. The evaluation phase of the dental hygiene process also provides the opportunity to identify other human needs related to oral health and disease that may require attention. As with all clients, the process of care is a continuum.

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Explain that periodontal health and oral conditions require frequent evaluation and maintenance, commonly every 2 to 3 months, to maintain and monitor oral health status.

Explain that periodontal health and oral conditions require frequent evaluation and maintenance, commonly every 2 to 3 months, to maintain and monitor oral health status.LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

KEY CONCEPTS

Risk of acquiring HIV infection from providing dental hygiene care to infected individuals is extremely low.

Risk of acquiring HIV infection from providing dental hygiene care to infected individuals is extremely low. Standard precautions (infection control) and efforts to eliminate risk of percutaneous exposure must always be taken.

Standard precautions (infection control) and efforts to eliminate risk of percutaneous exposure must always be taken. Most periodontal disease in HIV-positive individuals is indistinguishable from disease patterns seen in HIV-negative clients.

Most periodontal disease in HIV-positive individuals is indistinguishable from disease patterns seen in HIV-negative clients.CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge Dorothy A. Perry for her past contributions to this chapter.

Refer to the Procedures Manual where rationales are provided for the steps outlined in the procedure presented above.

1. UNAIDS/WHO. AIDS epidemic update: December 2007. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS and World Health Organization; 2007.

2. Kandathil A.J., Ramalingam S., Kannangai R., et al. Molecular epidemiology of HIV. Indian J Med Res. 2005;121:333.

3. Boswell S.L., Fuller J.D. Pathogenesis and natural history. In: Libman H., Makadon H.J., editors. HIV. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians, American Society of Internal Medicine, 2000.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case for AIDS among adolescents and adults, December 18, 1992. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00018871.htm. Accessed October 9, 2008.

5. Jacoby H.M., Currier J.S. Prevention of opportunistic infections. In: Libman H., Makadon H.J., editors. HIV. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians, American Society of Internal Medicine, 2000.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention: 2006 disease profile. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/Publications/docs/2006_Disease_Profile_508_FINAL.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2008.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and dependent areas, 2005. Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/2005report/pdf/2005SurveillanceReport.pdf. Accessed October 9, 2008.

8. Bell D.M. Occupational risk of human immunodeficiency virus infection in healthcare workers: an overview. Am J Med. 1997;102(Suppl 5B):9.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Exposure to blood: what healthcare personnel need to know. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; July 2003.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Surveillance of occupationally acquired HIV/AIDS in healthcare personnel, as of December 2006. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/bp_hcp_w_hiv.html#2. Accessed February 2008.

11. Tolle-Watts L., Saisbury M. Incidence of student exposures to blood and body fluids and postexposure management protocols in dental hygiene programs. J Dent Hygiene. 2001;75:214.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Updated U.S. Public Heath Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to HBV, HCV, and HIV and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. Available at: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5011a1.htm#box2. Accessed October 9, 2008.

13. Scheutz F., Matee M.I., Andsager L., et al. Is there an association between periodontal condition and HIV infection? J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:580.

14. Robinson P.G., Boulter A., Birnbaum W., Johnson N.W. A controlled study of relative periodontal attachment loss in people with HIV infection. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:273.

15. Perrson R.E., Hollender L.G., Perrson G.R. Alveolar bone levels in AIDS and HIV seropositive patients and in control subjects. J Periodontol. 1998;69:1056.

16. Zambon J.J., Reynolds H., Smutko J., et al. Are unique bacterial pathogens involved in HIV-associated periodontal diseases? In: Greenspan J.S., Greenspan D., editors. Oral manifestations of HIV infection. Chicago: Quintessence, 1995.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..