Chapter 13 Assessment of Acute-Onset, Severe Lameness

Field Diagnosis of the Injured Horse

The assessment of an acutely lame horse presents a challenge in diagnosis and in dealing with the people associated with the horse, particularly if lameness occurs at a competition. The horse may have fallen and been lame immediately or may have pulled up lame, and the veterinary surgeon may be called to examine the horse on course in full view of the public.

Ideally the horse should be transported to an examination area for comprehensive evaluation, but the veterinary surgeon must establish whether the injured limb requires support before the horse is moved. Although the horse may be very lame, establishing a definitive diagnosis for the cause of the lameness at this stage may be difficult.

This may surprise riders, trainers, and owners, and maintaining their confidence in what is an emotionally charged situation can be quite difficult. If a fracture is suspected, pressure to destroy the horse humanely without delay may be felt. Although some fractures are catastrophic and merit immediate destruction of the horse on humane grounds (e.g., a spiral fracture of the humerus), other serious fractures can be repaired. Therefore as much information as possible about the site of the fracture and its configuration should be obtained before a decision is made. The limb should be supported appropriately before the horse is moved for radiographic examination. If a horse must be destroyed on humane grounds at a competition, this should be done off the course.

Although a diagnosis may be obvious in some horses immediately after the onset of lameness, the veterinarian must recognize that severe lameness may occur without an evident cause. Serial reexaminations over the following hours or days may be required before a diagnosis can be reached. Sometimes the lameness resolves spontaneously within 12 to 18 hours and its cause is never established.

The clinician must be aware of the most common causes of acute-onset, severe lameness, which include the following:

When lameness occurs during training or competition, a spectrum of other injuries must be considered. However, a history of acute-onset, severe lameness during exercise must not mislead the clinician into thinking that lameness must be caused by internal or external trauma associated with exercise. Lameness may still be caused by pain from a subsolar abscess.

This chapter describes a systematic approach to management of a horse with sudden-onset, severe lameness and focuses particularly on injuries that occur during work.

Assessment

Medical History

While performing an initial visual appraisal of the horse, establishing a history is useful. The examiner must determine the following:

The clinician should also be aware of common injuries in the discipline in which the horse is competing.

The horse may be distressed because of the severity of pain and excited because of the atmosphere of a competition and thus difficult to restrain and examine adequately. Sedation with romifidine or detomidine, with or without butorphanol, may be necessary to facilitate examination of the horse. A horse with an acute hindlimb muscle tear or hemorrhage may show evidence of pain mimicking signs of colic.

The horse’s posture should be observed while it stands still and walks a few steps. If the horse bears weight only on the toe, it may be inapparent that the horse has lost some support of the fetlock because of rupture of the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) in the metacarpal region or at the musculotendonous junction in the antebrachium, unless it walks a few steps.

Limb Examination

The veterinarian should establish whether the horse is able and willing to bear weight on the limb, bearing in mind that after a fall a neurological component may contribute to the lameness, in addition to the pain. The horse’s demeanor should be assessed; the degree of pain and distress usually but not invariably reflects the severity of the injury. The horse may be greatly distressed, shifting weight constantly between limbs, and may be reluctant to move. Reluctance to move may be caused by a bilateral problem (e.g., bilateral severe superficial digital flexor [SDF] tendonitis) or a more generalized problem such as equine rhabdomyolysis (tying up).

The horse should be carefully appraised visually to identify areas of swelling or a laceration. If the horse’s limbs are covered in mud or grease (commonly applied to the limbs during the speed and endurance phase of a Three Day Event), this should be washed off before one proceeds with the evaluation. Boots, bandages, and the saddle and martingale should also be removed. Temporary studs in the shoes should be removed because they may be more difficult to remove later if the injury is severe.

The horse may be obviously lame on a hindlimb or forelimb, but this may mask a similar, less severe injury in a contralateral limb or a different injury; therefore all limbs should be assessed carefully. For example, a racehorse may develop a lateral condylar fracture of the third metacarpal bone in one limb and SDF tendonitis in the contralateral limb. Although the former injury results in a more severe lameness, the latter may be more important to the horse’s long-term prognosis.

Occasionally, forelimb and hindlimb lameness are concurrent. Each limb should be palpated systemically with the horse bearing weight and not bearing weight. The examiner should pay careful attention to heat, swelling, abnormal muscle texture, pain on firm pressure, pain induced by manipulation of a joint, restriction of flexibility of a joint, an abnormal range of motion of the joint, audible or palpable crepitus, and the intensity of the digital pulse amplitudes.

The position of the shoe should be assessed carefully. A shoe that has moved slightly may result in nail bind. Hoof testers should be systemically applied across the wall and sole, gently at first and then firmly. Percussion should also be applied to the sole of the foot with the limb picked up and to the wall with the limb bearing weight. The clinician should not forget that if the sole is very hard, eliciting pain with hoof testers may not be possible, despite the presence of a subsolar abscess.

The limbs should be carefully assessed for lacerations. Serious damage to underlying structures may have occurred if the laceration was sustained while the horse was moving at speed, and the position of the laceration and the site of damage to underlying structures may not coincide.

Shoulder and Chest

Injuries to the shoulder region usually result from a fall or collision, which may result in severe bruising only or a fracture. A fracture of the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula results in severe lameness (Figure 13-1). Slight soft tissue swelling may develop, usually without audible or palpable crepitus, and pain on palpation may be difficult to differentiate from that caused by severe bruising alone. Articular fractures of the scapula may be associated with audible crepitus on manipulation of the limb. Fractures of the body of the scapula or the humerus are usually associated with severe lameness, soft tissue swelling, and pain in that area.

Fig. 13-1 • Mediolateral radiographic image of the left shoulder of an advanced event horse that had fallen during competition 3 days previously and developed severe left forelimb lameness from a displaced comminuted fracture of the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula.

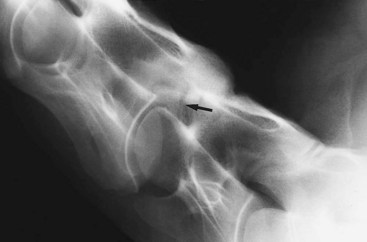

After collision with a fixed object, or occasionally a fall, the scapulohumeral joint may become luxated or subluxated, with or without a fracture of the glenoid cavity of the scapula. The horse bears weight on the limb reluctantly, soft tissue swelling develops rapidly, and the distal aspect of the scapular spine may become more difficult to palpate. The limb may appear straighter than usual. A collision also may result in collateral instability of the shoulder, so-called shoulder slip, usually caused by trauma to nerves of the brachial plexus. The horse may have pain-related lameness because of bruising, together with mechanical lameness caused by neurological dysfunction (Figure 13-2).

Fig. 13-2 • Lateral radiographic image of the midcervical region of a 6-year-old event horse that fell on a cross-country course. The horse was not bearing weight on the left forelimb and showed moderate hindlimb ataxia. The synovial facet joints were fractured between the sixth and seventh cervical vertebrae (arrow). A cause of the forelimb lameness was not identified, and the lameness resolved within 24 hours. The horse had a complete functional recovery but had some residual neck stiffness.

Although major fractures of the scapula and humerus are usually readily evident by clinical signs, most other shoulder injuries require radiographic and sometimes ultrasonographic examination for a diagnosis to be reached.

Pectoral muscle tears may result in similar clinical signs, with severe lameness and distress. Repeated clinical examinations may reveal the site of muscle rupture, with increasing evidence of hemorrhage, inflammatory effusion, and edema.

Rib fractures can also result from direct trauma or from falls and occur most commonly in steeplechasers and polo ponies. Fractures in the region of the scapula and triceps result in acute, severe forelimb lameness. More caudal fractures may result in extreme stiffness and may cause severe respiratory embarrassment.

Lameness associated with the upper forelimb may also be caused by strain of the biceps brachii or brachiocephalicus muscles or hematoma formation. Careful, deep palpation of these muscles is required to identify focal pain and possibly swelling or abnormal muscle texture.

Elbow and Carpus

Acute-onset lameness associated with pain arising from the elbow region is rare, except as the result of a fall or kick. Fracture of the olecranon process of the ulna is the most common injury (Figure 13-3). If the fracture is nondisplaced, the horse may stand normally but with severe pain; or if the fracture is complete with loss of triceps function, the horse stands with a dropped elbow.

Fig. 13-3 • Mediolateral radiographic image of left elbow of an event horse that was very lame after a fall and stood with the elbow dropped. The olecranon of the ulna sustained a displaced, comminuted fracture.

Acute-onset lameness associated with the carpus occurs most commonly in racehorses, both flat racehorses and steeplechasers, and usually is associated with a chip or slab fracture or less commonly with hemarthrosis. Synovial effusion within the antebrachiocarpal or middle carpal joint usually develops rapidly. The horse may resent maximal flexion of the carpus, and direct palpation of the carpal bones may elicit pain. Fracture of the accessory carpal bone usually results from a fall and occurs most commonly in steeplechasers; such fractures may be associated with effusion within the carpal sheath. Acute tears of the accessory ligament of the SDFT sometimes occur in polo ponies and rarely in trotters, with associated distention of the carpal sheath. Tenosynovitis caused by hemorrhage most often causes acute, severe lameness, but pain can be transient and intermittent.

Forelimb Soft Tissue Injuries

Injuries of the forelimb suspensory ligament (SL) (proximal, midbody, and branch lesions) and of the forelimb SDFT occur most commonly in racehorses and event horses, whereas desmitis of the accessory ligament of the deep digital flexor tendon (ALDDFT) occurs more commonly in show jumpers, older steeplechasers, and polo ponies.

Severe, apparently acute-onset lesions of the SDFT occasionally occur in show jumpers, especially those of international standard. Evaluation of the posture of the limb and the presence of heat, pain, and swelling are important for accurate diagnosis. Clinical signs associated with these injures can vary markedly. Substantial lesions of the SDFT can develop without detectable lameness, whereas a large tear can result in acute, severe, non–weight-bearing lameness. Bilateral tears may result in extreme distress, a reluctance to move, and a laminitic-like stance. In event horses, lameness can develop after the speed and endurance phase of a Three Day Event, associated with SDF tendonitis, but no clinical signs may suggest the injury. Swelling or localized heat and pain may take several days to develop despite improvement or resolution of the lameness. Therefore careful reappraisal of the horse over the next few days is strongly recommended if an event horse develops an acute-onset, forelimb lameness for which no diagnosis can be identified.

Rupture of the SDFT results in hyperextension of the fetlock with normal foot placement. Elevation of the toe with normal angulation of the fetlock indicates disruption of the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT). Hyperextension of the fetlock and elevation of the toe reflect laceration or rupture of the SDFT and the DDFT. Sinking of the fetlock to the ground indicates disruption of the suspensory apparatus, with or without the flexor tendons.

Severe lameness and distress, with hyperextension of the fetlock, without obvious swelling in the metacarpal region suggest rupture of the SDFT at the musculotendonous junction. This injury occurs most commonly in steeplechasers. Rupture of the SDFT usually is a sequela to a previous injury; therefore the tendon is generally chronically enlarged. Detection of the rupture is easiest at the peracute stage, before exudate and hemorrhage fill the deficit. The site of rupture is usually in the midmetacarpal region.

Desmitis of the ALDDFT usually causes acute-onset, moderate-to-severe lameness with rapid development of soft tissue swelling in the region of the ligament. However, recurrent injuries can develop with no detectable alteration of a chronically enlarged ligament. The degree of lameness associated with a SL injury varies from mild to moderate but may be worse if a concurrent fracture of the second or fourth metacarpal bone or of the apex of a proximal sesamoid bone exists, and these structures should be evaluated carefully. Some severely lame horses with proximal suspensory desmitis have no palpable abnormalities.

Each of the tendons and ligaments in the metacarpal region should be palpated carefully, from proximally to distally, with the limb bearing weight and picked up. The size, shape, and consistency of the tendons and ligaments and any pain on palpation should be carefully assessed. With severe SDF tendonitis, the horse may be distressed, and peritendonous edema rapidly develops, which makes accurate palpation of the tendon difficult. Partial rupture may be associated with a palpable soft defect in the tendon. Bilateral SDF tendonitis sometimes occurs, with the only detectable palpable abnormality being slight enlargement of each tendon and rounding of its margins. The clinician must be aware of this, because these lesions may be missed if one assumes that because the limbs feel symmetrical, the tendons are normal.

A caudal radial osteochondroma or exostosis may cause episodic acute severe lameness associated with dorsal tearing of the DDFT. When lameness is apparent there may be distention of the carpal sheath and/or pain on passive flexion of the carpus. Lameness and other associated clinical signs may resolve rapidly.

Fractures of the Distal Aspect of the Limbs

A fracture of the lateral, or more rarely the medial, condyle of the third metacarpal or metatarsal bone results in acute-onset, severe lameness. If the fracture is incomplete and nondisplaced, no palpable abnormality may be detectable, although some effusion in the metacarpophalangeal joint usually develops within 12 to 24 hours. The horse may resent fetlock flexion; however, some horses become so distressed that in the acute phase, determining whether pressure or joint manipulation causes pain is impossible. The same can apply for a fracture of the proximal phalanx.

Subluxation of the metacarpophalangeal joint occasionally occurs, with disruption of a collateral ligament, with or without an associated fracture. The horse may be very lame, but during normal load bearing the joint may appear to be aligned normally. Instability of the joint may be detectable only with the joint stressed with the limb not bearing weight.

Feet

Trauma to the palmar aspect of the pastern may result in an innocuous skin wound but severe damage to the underlying soft tissue structures. The branches of the SDFT, the DDFT, and the digital flexor tendon sheath are particularly vulnerable. Posture of the limb should be carefully assessed to determine which structure or structures may be involved.

An overreach injury on the bulb of the heel can result in severe, deep-seated bruising and lameness, especially on hard ground. Injuries of the foot are common, especially in event horses. The differential diagnosis should include subsolar hemorrhage (especially corns), nail bind, a subsolar abscess, and a fracture of the distal phalanx.

If the horse shows any reaction to percussion of the foot or pressure applied with hoof testers, the shoe should be removed for further exploration of the foot. If the horse is very lame, removal of each nail individually using nail pullers may be preferable to levering off the shoe. The absence of reaction to hoof testers and normal digital pulse amplitudes does not preclude the existence of either laminitis or a subsolar abscess.

Hindlimb Injuries

When one examines a horse with acute hindlimb lameness that developed during exercise, consideration should always be given to tying up, even if the hindlimb musculature feels soft, local pain cannot be elicited, and the horse is not unduly distressed. The clinical manifestations of tying up vary considerably from acute, severe bilateral or unilateral hindlimb lameness with obvious firmness of the muscles of the hindquarter, with or without swelling, to a moderate unilateral hindlimb lameness that developed after the horse was not moving as freely as normal, with no detectable palpable abnormality. This lameness may persist for several hours but usually resolves within 12 to 18 hours. Occasionally, tying up can affect forelimbs, alone or together with the hindlimbs.

Measurement of substantially raised serum creatine kinase concentration 3 to 24 hours after the onset of lameness may be the only way to reach a definitive diagnosis. Alternatively, a horse may not be moving as freely as normal during a competition and subsequently may be withdrawn; further clinical signs may not develop.

Major hindlimb muscle rupture of quadriceps, semimembranosus, gastrocnemius, adductor, gracilis, or abdominal muscles results in severe lameness and distress, but diagnosis may be difficult. Careful palpation may reveal a site of rupture. Detection of acute muscle strains may be possible when superficial muscles are involved. Pain on palpation and sometimes swelling may be present; however, this is not always the case, and evaluation of deep muscles is limited. Swelling may become more apparent over the next several days.

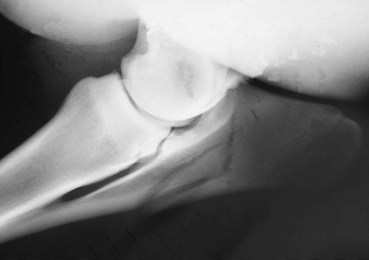

Stifle trauma is common in horses that jump fixed fences at speed, even if the rider cannot recollect the horse hitting a fence. Lameness caused by a fracture may be sudden and severe in onset, and the horse may pull up, but in some horses it does not become apparent until the horse has finished.

Because the cranial aspect of the stifle is relatively poorly covered with soft tissues, the bones are particularly susceptible to bruising or fracture (Figure 13-4). The degree of pain on palpation does not necessarily reflect accurately the severity of the injury. Development of femoropatellar or femorotibial effusion or marked periarticular soft tissue swelling suggests a fracture. Sometimes a displaced fragment of bone can be palpated. The superficial location of the femoropatellar joint capsule also makes it vulnerable to puncture and the introduction of infection, and effusion and severe lameness may develop rapidly.

Fig. 13-4 • Cranioproximal-craniodistal oblique radiographic image of right stifle of an event horse that hit the penultimate fence at the World Equestrian Games. The horse completed the course, pulled up slightly lame, and was very lame within a few hours. The arrows show an articular fracture of the medial pole of the patella.

Most horses with stifle injuries require radiographic examination to establish or confirm the presence of a fracture. Although lameness associated with bruising may initially be severe, the horse generally rapidly improves within 24 to 48 hours, whereas with most fractures the lameness usually persists unchanged. The horse may be reluctant to extend the stifle and tends to stand with the limb semiflexed and the weight on the toe, a posture also typical of severe foot pain. Occasionally, severe ligamentous injury that cannot be detected radiologically occurs in the stifle.

Periarticular hemorrhage around the patellar ligaments can result in acute pain and lameness characterized by a shortened cranial phase of the stride at the walk, but less severe lameness at the trot. Swelling may be subtle, resulting in loss of definition of the patellar ligaments; diagnosis is dependent on ultrasonographic examination.

Rupture of the fibularis tertius usually results from a traumatic episode, with the limb getting trapped in an extended position, and results in a severe lameness with the horse unwilling to load the limb fully. Passive extension of the hock is pathognomonic.

Acute injuries to the hock are uncommon, unless the horse has a severe fall resulting in damage to the hock joint capsules and the collateral ligaments or a lateral malleolar fracture of the distal aspect of the tibia. The horse usually is severely lame and rapidly develops distention of the tarsocrural joint capsule and periarticular soft tissue swelling. Radiographic examination is indicated to determine the extent of the damage. Less commonly, slab fractures of the central or third tarsal bone or incomplete sagittal fractures of the talus cause acute, severe lameness, often with no localizing clinical signs. Kick injuries may result in a fracture. Whereas intuition would suggest that kick wounds should most likely involve the lateral aspect of the tarsus, often the medial tarsal or proximal metatarsal region is involved. Careful interpretation of radiographs may be necessary to detect small fragments displaced from the sustentaculum tali, on the distal medial aspect of the calcaneus.

Displacement of the SDFT from the tuber calcanei may occur suddenly, resulting in marked distress, especially if the tendon continues to move on and off the tuber calcanei. The tendon may slip laterally, or less commonly medially, and occasionally splits. Peritendonous soft tissue swelling develops rapidly. The horse is reluctant to bear weight on the limb and characteristically shows extreme distress, caused by pain or instability. Careful palpation usually confirms the diagnosis, although acute soft tissue swelling may make this difficult in the initial period after injury.

Periarticular cellulitis of the tarsal region results in an extreme lameness associated with the rapid development of extensive soft tissue swelling, which is exquisitely sensitive to touch (see Chapter 107). The horse is often lamer than with a fracture, and swelling is more extensive than with synovial infection.

Injuries to the soft tissue structures of the metatarsal and pastern regions are less common than those of the metacarpal and forelimb pastern regions. Suspensory branch injuries are the most common injuries resulting from direct blunt trauma. Acute tears of the DDFT may occur within the digital flexor tendon sheath, with rapid development of effusion. Fractures of the third metatarsal bone and phalanges are also less common than in the forelimbs, except in barrel racing or cutting horses or polo ponies. Plantar process fractures of the proximal phalanx are rare but do occur in racehorses and result in moderate-to-severe lameness, with pain on manipulation of the fetlock, effusion, and in some horses periarticular soft tissue swelling, especially on the plantar aspect. Stability of the fetlock should be assessed carefully.

Stress Fractures

In young Thoroughbred racehorses the possibility of a fatigue or stress fracture must always be considered. The most common sites are the humerus, radius, ilial wing, tibia, third metacarpal bone, and tarsus. With the exception of ilial wing fractures, in which asymmetry of the tubera sacrale and pain on palpation in this area may be obvious, localizing clinical signs may otherwise be absent. A definitive diagnosis can rarely be made by clinical examination alone.

Hemarthrosis

Hemarthrosis may occur in any joint and results in acute-onset, non–weight-bearing lameness associated with distention of the joint capsule. Lameness often improves rapidly within the following 48 hours. Diagnosis is based on ultrasonography and synoviocentesis. Draining blood from the joint produces rapid relief of clinical signs.

Transportation

In any horse with severe lameness in which making a tentative diagnosis based on a preliminary but thorough clinical examination is not possible, a decision has to be made about whether the horse is fit to travel, whether any risks are involved in travel, and whether the horse should be stabled as close as possible and be reassessed later or the following day (if this is practical). Whether the horse is insured should be established, together with the terms of the insurance policy.

The majority of horses can be taken safely to the nearest adequate diagnostic facility, which ideally should have a loading ramp, a veterinarian experienced in orthopedics, facilities for hospitalization, and high-standard radiographic, ultrasonographic, and possibly nuclear scintigraphic equipment.

Facilities for orthopedic surgery are not necessarily essential, although they are desirable, because the first step must be to reach an accurate diagnosis. When a diagnosis has been reached, the limb may then be appropriately supported to minimize risks of exacerbating the injury, if the horse is to be treated conservatively; during induction of general anesthesia; or for transfer to a suitable surgical facility. If a hindlimb fracture is suspected, the horse should be tied up (cross-tied). For transport for further diagnostic investigation or surgical treatment the injured limb should usually be supported using a Robert Jones bandage,1 with or without splints, or an appropriate commercial splint, bearing in mind the proposed site of injury2 (see Chapters 86 and 104). For forelimb injuries the horse should ideally travel facing backward, although some low-loading ambulances are not designed for loading from the front.3 When possible a low-loading trailer should be used, but if this is not available, the ramp of the vehicle should be placed on a slope to minimize the gradient for loading and unloading. If a diagnosis has been made for a horse with an injury that requires rapid surgical treatment, the limb should be supported in the most appropriate way and the horse referred to the nearest surgical facility, or to the best surgical facility in close proximity to the horse’s place of origin, or to the person with the most expertise and experience dealing with that kind of injury. Provided that the limb is adequately immobilized and adequate pain relief is possible, the horse should be fit to travel several hours safely and humanely.

Guidelines for Humane Destruction of an Injured Horse

If the horse is insured for all risks of mortality, owners, trainers, and other interested people may request humane destruction. The American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) and the British Equine Veterinary Association (BEVA) have issued guidelines indicating the requirements that should be fulfilled to satisfy a claim under a mortality insurance policy. Nonetheless, the decision to advise an owner to destroy a horse on humane grounds must be the responsibility of the attending veterinary surgeon, based on the assessment of clinical signs at the time of the examination or examinations, regardless of whether the horse is insured. The veterinary surgeon’s primary responsibility is always to ensure the welfare of the horse. On occasion the attending veterinary surgeon will advise euthanasia, but such a decision may not necessarily lead to a successful insurance claim. It is important that all parties be aware of these potential conflicts of interests before a horse is destroyed. The owner’s responsibility is to ensure compliance with any policy contract with an insurer.

The AAEP has issued the following guidelines for recommending euthanasia:

The AAEP recommends that the following criteria should be considered in evaluating the immediate necessity for intentional destruction of a horse. It should be pointed out that each case should be addressed on its individual merits and that the following are guidelines only. Not all criteria must be met in each case.

Justification for euthanasia of a horse for humane reasons should be based on medical grounds, not economic considerations; and further the same criteria should be applied to all horses regardless of age, sex or potential value.

The BEVA guidelines for compliance for a mortality insurance policy are as follows:

That the insured horse sustains an injury, or manifests an illness or disease, that is so severe as to warrant immediate destruction to relieve incurable and excessive pain, and that no other options of treatment are available to that horse, at that time.

If immediate destruction cannot be justified, then the attending veterinary surgeon should provide immediate first aid treatment before:

It is essential that the attending veterinary surgeon keep a written record of the injuries sustained by the horse, its identification, and the date, time, and place. The owner or agent should whenever possible sign a form consenting to euthanasia. Insurance companies frequently require some form of examination after death and may request an independent postmortem examination, and this must be borne in mind when arranging for disposal of the carcass.