Chapter 104Catastrophic Injuries

Surprisingly, it is difficult to define exactly what comprises a catastrophic injury, but one definition might be any injury that will unquestionably end athletic function and will require extensive treatment to save the horse’s life. Comminuted fractures, severe limb lacerations with major vascular damage and extensive tissue loss, and ligamentous injuries leading to overt joint instability are straightforward examples and are easily categorized as “catastrophic.” Problems arise when the gross appearance of an injury is initially not representative of its severity or when the severity of the injury is overestimated because of its gross appearance. The attending veterinarian often has to calm the client long enough to allow proper decision making. Most horses with catastrophic injuries can be stabilized well enough to be transported to a referral facility, or at least long enough to permit a complete investigation of therapeutic options and probable outcomes. A quick decision to euthanize might be the easiest and best option, but in some instances it may not be correct, and it most certainly is not revocable.

General principles for emergency first aid of severe distal limb injuries are as follows:

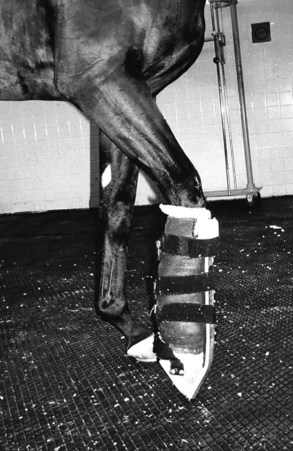

Fig. 104-1 A Kimzey Leg Saver has been applied to the right forelimb of a racehorse with traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus. Note that the distal aspect of the limb is held in position with a dorsal splint attached to a footplate that keeps the phalanges in alignment with the third metacarpal bone. When splinted horses usually comfortably bear weight when walking, they stand with the splinted limb forward in a flexed non–weight-bearing position (as shown). Excessive load is placed on the contralateral limb. Limb length disparity occurs as a result of the added length of the splint, making it necessary to elevate and pad the contralateral foot (not shown).

The reader is referred to Chapter 86, and there are two excellent recent reviews that detail emergency stabilization of equine fractures.1,2

Types of Catastrophic Injuries

Traumatic Disruption of the Suspensory Apparatus

Traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus is almost exclusively an injury that occurs in the forelimbs of Thoroughbred (TB) racehorses, but it can occur in the hindlimbs and in Standardbred (STB) and Arabian racehorses. It may occur more often in North America than in Europe, although any horse running at high speed may sustain this injury, including young foals that are chasing the dams in a pasture. Speed alone does not account for the injury, and it is likely that fatigue of the flexor muscles supporting the fetlock joint and digit leads to higher stresses in each component of the suspensory apparatus. There also may be a history of the horse being bumped or making a misstep.

The history and clinical presentation of adult horses with traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus are straightforward, because the horses are either breezing or racing and pull up acutely and severely lame. The fetlock joint drops as the horse attempts to bear weight. Many horses become anxious or even frantic as they attempt to control the injured limb. Obvious swelling and pain are present over the site of the injury. In foals the diagnosis is often not made as quickly.2,3 The typical history of a foal with traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus (or lesser injuries of the suspensory apparatus) is of being turned out in a large field with its dam and other mares and foals shortly after birth, or after confinement to a box stall for an extended period. As the mare runs with the other horses, the foal attempts to keep up, running at speed and to the point of exhaustion. This results in the same combination of speed and fatigue that leads to this injury in racehorses. The clinical signs of complete disruption of the suspensory apparatus in foals are similar to those in adult horses but less dramatic.

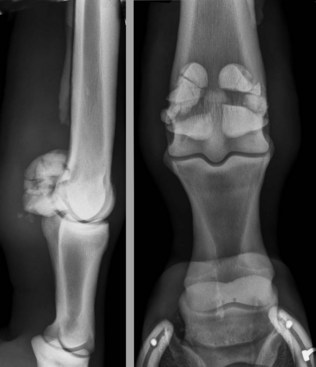

The hallmark clinical signs, fetlock drop and severe lameness, are seen in horses with complete disruption of any portion of the suspensory apparatus. The most common injury in both adult horses and foals is fracture of both proximal sesamoid bones (PSBs) (Figure 104-2). The fractures are often comminuted, especially in the basilar portions. The second most common type of traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus is complete avulsion of the distal sesamoidean ligaments. This is easily recognized radiologically by the proximal displacement of the intact PSBs (Figure 104-3). The least frequently recognized type of traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus is a complete tear of the body or both branches of the suspensory ligament (SL) (Figure 104-4). The Paso Fino, Peruvian Paso, and some other older horses have a degenerative condition of the SL that leads to suspensory apparatus failure that is particularly problematic in the hindlimbs. However, these horses do not have acute, severe lameness, which is typically seen in racehorses (see Chapter 72). In horses with traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus, excessive extension of the fetlock may result in stretching and damage to the digital vessels, which may cause avascularity or hypovascularity of the digit. Simultaneous damage to the superficial and deep digital flexor tendons is also common and should be assessed ultrasonographically if there is a suspicion of severe injury. Although PSB fractures and suspensory injuries are both common hindlimb injuries, the most severe breakdown injuries usually involve the forelimbs.

Fig. 104-2 Lateromedial (left) and dorsopalmar radiographic images of a Thoroughbred racehorse with traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus as a result of comminuted fractures of both proximal sesamoid bones. The radiographs were obtained with the horse in a non–weight-bearing position. This horse later underwent successful surgical management using fetlock arthrodesis.

Fig. 104-3 Lateromedial (left) and dorsopalmar radiographic images of a Thoroughbred racehorse with traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus as a result of complete rupture of the distal sesamoidean ligaments. Proximal displacement of the proximal sesamoid bones and hyperextension (drop) of the fetlock joint can be seen in these weight-bearing radiographic images.

Fig. 104-4 Lateromedial radiographic image of a horse with traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus as a result of a nearly complete tear of the body of the suspensory ligament. A similar appearance is observed in horses with severe injury of both branches of the suspensory ligament. Dorsal subluxation (hyperflexion) of the proximal interphalangeal joint occurs as a result of suspensory ligament disruption. Surgical or nonsurgical management can be chosen in horses with this injury.

Traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus is virtually always a career-ending injury. The only exceptions are horses with simple, displaced midbody fractures of both PSBs that can be individually repaired and suspensory body or branch injuries in some STBs. It is important to recognize the severity of the injury so that an informed decision can be made concerning treatment. Most horses can be saved as pasture sound or breeding horses, but treatment often is prolonged and expensive regardless of the therapeutic approach selected.

First Aid

As outlined previously, an important principle is to align the McIII and the phalanges using a homemade splint or a commercially available splint (see Figure 104-1). I much prefer the commercially available splint. Most horses are less anxious and are able to move comfortably immediately after the splint is applied. Other first aid measures include the administration of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), intravenous fluids to replace water and electrolytes lost through sweating, and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Antibiotics should be given even if the fracture is ostensibly closed. High concentrations of antibiotics in the fracture hematoma are desirable, because skin abrasions and lacerations over hypovascular tissue are common. The vascularity of the foot should be assessed by palpation of the digital vessels and assessment of hoof temperature. Aspirin may be of some value in limiting the vascular injury. Horses that are extremely anxious and difficult to calm should be given xylazine or detomidine, with or without butorphanol, as needed for restraint and to prevent further self-injury.

Nonsurgical Management

Nonsurgical management involves long-term splinting with a goal of achieving sufficient fibrosis of the injured tissues that satisfactory support of the fetlock returns. The primary advantage of this approach is avoiding the risks associated with operating in a hypovascular and possibly contaminated surgical site. The surgical and technical expertise and equipment required are modest, and the expense of initial treatment is relatively small. There are serious disadvantages of nonsurgical management. Developing fibrosis may not be adequate to support the fetlock joint in a horse exercising at pasture; this is more problematic in horses with distal sesamoidean ligament avulsions than fractured PSBs. Scar tissue may slowly fail when stallions enter a breeding shed or a mare carries a foal. Most horses are uncomfortable on the splinted limb and cannot use it normally because of an abnormal posture (see Figure 104-1), and they are at risk for supporting limb breakdown and laminitis. Long-term splinting also demands meticulous daily bandage changes to prevent rub sores at the proximal dorsal metacarpal region and suppurative dermatitis of the palmar aspect of the pastern and heel bulbs. In my opinion, nonsurgical management is not the best choice in most horses with traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus, especially those with comminuted fractures of the PSBs, or rupture of the distal sesamoidean ligaments.

Successful long-term splinting of horses with traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus involves meticulous nursing care. Most clinicians use a prefabricated splint because of the ease of its removal and application. The Kimzey splint can be improved for long-term use by welding on a heel extension to increase the load-bearing surface area. This helps minimize the tendency to develop rub sores at the proximal, dorsal edge of the splint. The prefabricated splints are not perfectly fitted for every horse. Therefore some modifications in padding may be required to avoid excessive pressure at the proximal, dorsal metacarpal region. Regardless of which type of splint is used, the limb should be checked daily for developing sores or dermatitis, particularly in the palmar aspect of the pastern. If the leg is washed, it should be dried before a bandage is applied. Skin infection can be very difficult to manage. Both systemic and local antibiotics are usually necessary. A shoe with a thick pad and heel elevation should be applied to the contralateral foot. A thick shoe is necessary to mitigate the limb-length discrepancy that exists when the contralateral limb is splinted, but it is difficult to give an exact degree of heel elevation.

The most critical decisions when using nonsurgical management of a horse with traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus with splints are when to remove the splints and how to gradually return the horse to more normal fetlock and digit joint angles. Upright splinting is used in most horses for approximately 6 weeks, but many, particularly those with distal sesamoidean ligament avulsions, may require much longer. The process of dropping the fetlock should be gradual. This can be done by splinting at decreasing angles (a difficult task when using a prefabricated splint) or using a fetlock support shoe incorporating an adjustable sling. Horses should be confined to a stall for a prolonged period (4 to 6 months), because a single misstep can lead to tearing of the still-maturing scar tissue. Although external coaptation has worked well in individual horses and in some clinicians’ hands, long-term results do not appear to be as good as surgical arthrodesis (fusion). Surgical fusion has considerable potential complications, but solid fusion of the fetlock joint is unlikely to slowly fail and cause progressive discomfort in horses used for breeding. Horses in which nonsurgical management was used appear to have more long-term lameness problems when compared with those in which surgical management was used. The more serious the injury, the less likely it is that a nonsurgical approach will prove satisfactory. Although a splint will definitely allow adequate early management, both laminitis at 6 to 8 weeks postinjury and chronic pain or instability when the splint is removed occur commonly.

Surgical Management

Surgical management of horses with traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus generally involves fetlock arthrodesis, although repair of simple, displaced midbody fractures of the PSBs can be performed to preserve some degree of fetlock joint function. The major advantage of arthrodesis is that the procedure usually affords the horse immediate, comfortable use of the limb and, barring surgical infection or failure, avoids the problems associated with prolonged overload of the contralateral limb. Because the fixation is usually very stable, postoperative immobilization is minimal, and the various complications of casts and splints can be avoided. The primary disadvantage of surgical arthrodesis is an increased risk of infection when compared with nonsurgical management. In addition, successful arthrodesis requires both surgical expertise and investment in equipment and facilities.

The most widely used technique for fetlock arthrodesis is the application of a dorsal plate and the creation of a tension band on the palmar aspect of the fetlock joint.3 Dorsal plating without a tension band on the palmar aspect of the fetlock is ill-advised because the plate is cycled in bending and the fixation may fail. Cyclic fatigue of even a large bone plate consistently results in plate failure unless a tension band technique of some sort is used. There are small variations in the techniques preferred by experienced surgeons with this procedure, but all have the same primary mechanical goals. I currently use a 10-hole, broad locking compression plate with a combination of 5.0-mm locking head screws and 5.5-mm cortex screws, and two 1.25-mm wires placed in figure-eight fashion along the palmar aspect of the fetlock joint.

The major complication of internal fixation for fetlock arthrodesis is infection. However, because this repair is very strong and stable, healing can occur even in the face of infection. The combination of instability and infection, however, rarely results in success, and reoperation on horses with unstable, infected sites is usually necessary to achieve fusion. Implant failure also is a concern, but proper technique and the use of large screws make this complication uncommon.

A common long-term complication associated with traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus is osteoarthritis of the proximal or distal interphalangeal joints. The joints are stressed by the fusion of the fetlock joint and often by the presence of serious injury to the digital flexor tendons and distal sesamoidean ligaments that insert on the phalanges.

Many horses with traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus sustain open, contaminated fractures or such extensive soft tissue damage that internal fixation may carry an unacceptable risk of infection. External skeletal fixation is an alternative means of managing horses with such injuries (see Chapter 87).

The prognosis for any horse with traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus depends on the specific nature and severity of the injury. Horses with distal sesamoidean ligament avulsions have a poorer prognosis than those with displaced fractures of the PSBs, because the latter tend to form fibrous scar tissue more quickly. Horses with the relatively uncommon suspensory body or bilateral branch tears have the best prognosis, because they seem to heal more quickly and have less fetlock joint instability. At least 60% to 75% of horses with closed disruptions of the suspensory apparatus and an intact blood supply should be saved with proper treatment. Horses with open injuries have a much poorer prognosis regardless of the therapy chosen, and those with open injuries with vascular compromise have a very poor prognosis.

Additional complications of traumatic disruption of the suspensory apparatus, regardless of treatment, include laminitis or breakdown of the contralateral limb. The primary complications of long-term splinting are rub sores and inadequate fibrosis, which lead to instability and chronic pain.

Other Catastrophic Distal Limb Fractures

Horses with other distal limb fractures have highly variable prognoses, but most horses with catastrophic fractures of the distal extremity can be successfully treated (for life if not function) if proper first aid and technically competent surgical treatment are performed. It is critical to prevent skin penetration of bone fragments, vascular injury, and prolonged delays in treatment. Because distal limb injuries can nearly always be temporarily immobilized relatively easily, decisions to euthanize should be made only after having informed discussions with the owner.

Severely comminuted fractures of the proximal and middle phalanges can be managed with the relatively simple technique of transfixation pin casting (Figure 104-5).4,5 The important advantages of transfixation techniques are that they are technically easy to perform and provide consistent early comfort. Without an open approach to the fracture site the surgeon can avoid causing further damage to already severely compromised tissues. The major disadvantages of transfixation techniques are catastrophic fractures through the pin holes and early loss of acceptable comfort from pin loosening or infection.

Fig. 104-5 Lateromedial and dorsopalmar radiographic images of a horse with a comminuted fracture of the proximal phalanx stabilized using transfixation pin casting. This type of fixation allows immediate weight bearing and obviates the need to invade the fracture site and further compromise injured soft tissues. Eventually both the metacarpophalangeal and the proximal interphalangeal joints will fuse, but horses with catastrophic phalangeal fractures can be salvaged using this technique.

Horses with major fractures above the carpus and tarsus are not as easy to deal with humanely on an emergency basis. It is certain that any overtly unstable fracture in the proximal limb will be an extremely expensive proposition to address surgically and that the prognosis is always guarded to poor at best. The only common exception might be horses with humeral fractures that may successfully heal with just stall confinement.