Chapter 25 Thermography

Use in Equine Lameness

Infrared thermography has been used in equine orthopedics for a number of years.1 Improvements in imaging quality and technology now yield images that are easier to interpret. The systems are also more cost effective. Thermography pictorially represents the surface temperature of an object and is a noninvasive method of detecting superficial inflammation and thus can have a role in lameness diagnosis. It is a physiological imaging modality, as is gamma scintigraphy, and thus has a lower reproducibility than anatomical imaging modalities such as radiography and ultrasonography. Superficial blood flow is a dynamic system and is likely to be variable and is also prone to artifacts, which has led some people to doubt its clinical applicability. Others consider it useful in the diagnosis of a large number of diverse conditions.2 With experience and care in interpretation, thermography can be a useful adjunct to lameness evaluation, as part of an integrated clinical and imaging approach. Eddy and co-workers reported a 63% correlation among thermographic findings in 64 horses and ultrasonography, nuclear scintigraphy, and radiography.3

Heat is lost through the skin by radiation, convection, conduction, and evaporation.4 Thermal cameras assess infrared radiation from an object; this is optically focused, collected, and transformed by detector arrays into an electronic signal that in modern systems then generates a real-time video image. The skin and hoof derive their heat from tissue metabolism and local circulation, and because the former is generally constant, variation in superficial temperature normally relates to changes in local tissue perfusion. Radiation from the equine foot and limb is more important than reflection, and lighting levels are not a major concern. Thermographic evaluation of the foot and distal aspect of the limb is complicated by the thermoregulatory role of the distal aspect of the limb, whereby the blood supply can be dramatically reduced to conserve heat in cold conditions.5 Thus an understanding of the physiology of the distal aspect of the limb is essential for optimal image interpretation.

Several different thermal imaging systems are available. Older systems were primarily developed for military or industrial applications and are relatively cumbersome and have poor image quality. The top-end systems have a cooling system to ensure temperature stability of the detector, and this increases the fragility of the system and the maintenance costs. Uncooled camera technology is preferable in a veterinary environment because it is cheaper, lighter, and more robust. These systems have become more available recently, and the system cost for diagnostic-quality thermographic imaging is no longer prohibitive. There is still wide variation in the image quality among different systems, and it can be difficult to compare different systems, but the user becomes used to the particular thermal patterns produced by each machine. Some systems are also radiometers and allow an accurate temperature measurement to be obtained, whereas other systems do not measure the absolute temperature but are able to determine the difference between two areas within the same image. Although a radiometer is not essential, it does assist in comparisons among different examinations. Higher image quality leads to a greater ease of interpretation of the image. The quality of image processing software is also improving, but the majority of interpretation is carried out in real time. Images can be stored in a variety of digital formats for archiving and later comparison. Infrared thermographic instrumentation is far more sensitive than human hands in detecting temperature changes in an object. There may be variability of up to 1° C attributed to the camera in clinical imaging,6 and differences of over 1° C are normally deemed as being potentially clinically significant in image interpretation.

Image Acquisition

Imaging should be performed in a relatively bare room without radiant heat sources, drafts, or sunlight. Some clinicians recommend allowing the horse to thermally equilibrate in the environment in which it is to be imaged. Equilibration can take up to 1 hour, but although the absolute temperature changes, there is little change in the relative thermal pattern.6 Thus equilibration is not necessary for clinical imaging. The optimal ambient temperature for imaging is 20° to 25° C. Below this temperature the distal aspect of the limbs are more prone to thermal cutoff,5,7 and above this range the contrast between the horse and the background is lost. Thus in colder temperate climates it can be advantageous to have a “hot box” to raise the ambient temperature if thermal cutoff prevents diagnostic imaging. It can also be advantageous to image the feet after the horse has been trotted and lunged, which increases the blood supply to the limbs and hence increases the inherent contrast of the digit relative to the background.

A long hair coat acts as an insulator and reduces the contrast within the image. Irregular patterns of clipping, topical applications, and dirt can complicate interpretation of images. Bandages and rugs should be removed at least 20 minutes before imaging. The feet should be clean for thermographic imaging of the digit and should be picked out and brushed to remove external contamination.

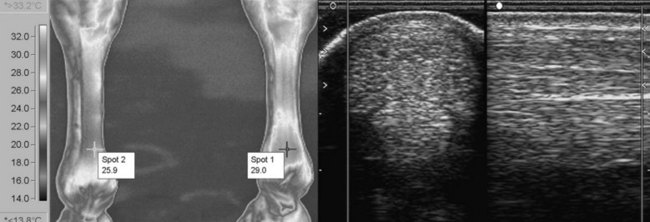

The distal aspect of the limb should be imaged from a dorsal position, from a palmar or plantar direction, and from the left and right sides. The limbs are then lifted, and a solar view is obtained of the feet (Figure 25-1; Color Plate 1). The joints of the proximal aspect of the limbs should be imaged cranially and laterally. The neck is imaged from the side. The back and hindquarters should be imaged as dorsally as is possible. Close-up images of regions of interest can then be performed if necessary. Comparisons should be made between sides; it can be helpful to repeat the imaging on another occasion if the results are uncertain.

Fig. 25-1 Normal dorsal, palmar, left lateral, and solar thermographic images of the distal aspect of the forelimbs of a horse. There is good symmetry between the limbs. The coronary band is the warmest area, and the rest of the hoof becomes colder in a regular pattern closer to the ground surface. The palmar image shows a normal increase in heat between the heel bulbs. On the solar image there is a V-shaped pattern of increased heat representing the sulci of the frog.

It is normally most intuitive to image using a rainbow color palette, with as great a range of color depth as the system allows. There is variability in the absolute temperature of the distal aspect of the limb; therefore the thermal range should be adjusted for each individual horse. The coronary band is normally the warmest area within the image, reflecting its high vascularity. The temperature level and span of the camera are adjusted to use the whole color range for the image. The coronary band normally appears white, and the coldest part of the image is blue or black, thus maximizing the visual contrast within the image. Some cameras have an automatic setting that constantly readjusts the image in this way. This does not allow comparison of left-to-right symmetry and thus is not useful clinically.

The camera should be carefully focused, and a series of still images obtained. The absolute temperature of points of interest can be determined using a radiometer so that absolute temperature differences can be calculated. Some systems allow more detailed analysis of the images on a computer, including calculation of mean temperature within regions of interest or graphically along lines of interest. The software tends to be expensive, and there is a greater need for such images in research than in a clinical setting.

Clinical Imaging

Figure 25-1 demonstrates a series of normal images of the distal aspect of the limb and digit. The coronary band is the warmest part of the image, and the hoof becomes progressively cooler toward the ground surface. The bulbs of the heel are also warm. On the solar image, the frog sulci appear warmest, as there is less tissue depth in this area. Heat generally follows the pattern of blood vessels so the medial metacarpal region is normally warmer than the lateral. Ideally the limbs appear symmetrical, but there can be variation in normal horses, especially at low ambient temperatures.4,5 Thermoregulatory cutoff is variable, and there are intermittent periods of vasodilatation, which is not necessarily symmetrical between left and right4 nor front and hind feet. Reevaluation of the horse some hours later may yield a different image. Exercising the horse for approximately 20 minutes or administering vasodilators such as acepromazine can increase the temperature to allow diagnostic imaging. Thermoregulatory cutoff in the distal aspect of the limb dramatically reduces the temperature and thus the contrast; therefore, subtle lesions may be missed. However, severe inflammation causes a sufficiently increased blood flow to be detectable.

Thermography is sensitive at detecting the presence of superficial inflammation within the foot, and in my opinion this is one of the more useful areas to image clinically.8 Conditions such as subsolar or coronary band infections result in a marked increase in temperature; corns and subsolar bruising may also be associated with increased temperature. Horses with chronic palmar foot pain and navicular syndrome do not show superficial inflammation and have either normal thermographic patterns or a colder pattern than normal, especially in the heel region. The temperature in the heel does not increase after the horse is exercised,6,7 probably because of a decrease of loading in this area rather than inherent ischemic disease. Superficial foot inflammation can obviously be diagnosed clinically without thermographic imaging in the majority of horses. Thermography is helpful in horses for which there is the suspicion of deep pathology, but also for those with mild signs of inflammation and response to hoof testers. Thermography can be helpful in optimizing the efficiency of a lameness evaluation, especially close to competition and in an extremely fractious horse, where it is advantageous to minimize the amount of diagnostic local analgesia employed. Thermography can also be used to assess foot balance. When a horse with metal shoes is trotted on a hard surface and immediately imaged, the side taking the greatest load appears warmer when the shoe is imaged. In horses with substantial mediolateral imbalance that land lateral wall first and roll over to the medial side during weight bearing, there can be an increased temperature over the coronary band medially, rather than on the side that lands first.

Thermographic evaluation can also be useful in monitoring laminitis. In acute laminitis there is increased heat within the foot.4 The normal gradation of temperature from the coronary band to the sole is lost as the temperature on the dorsal hoof wall approaches that of the coronary band. On solar images there may be an increased temperature in the region of the tip of the distal phalanx. In chronic laminitis there may be areas of decreased temperature in the dorsal aspects of the coronary band and the hoof wall, indicating decreased perfusion and laminar separation. This is a poor prognostic indicator.

Joints are best evaluated from the dorsal aspect and tend to be cool in comparison to surrounding tissues except where there are superficial vessels. Acute inflammation can occasionally give an increased heat pattern, but chronic pathology is not normally detectable. Early signs of joint inflammation can reportedly be detected 2 weeks before lameness resulting from osteoarthritis in Thoroughbred racehorses,9 allowing modification of training regimens to decrease the risk of serious injury.

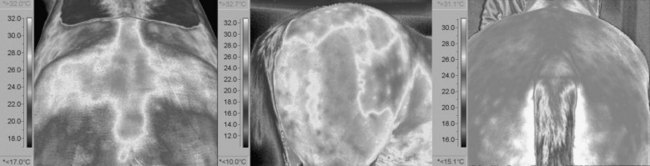

The superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) can be usefully imaged thermographically. The midportion of the tendon is bilaterally symmetrical, whereas the proximal and distal portions are reduced in temperature. The majority of horses with tendonitis have localizing clinical signs and ultrasonographic abnormalities. Thermography can be useful as a routine screening procedure when dealing with a large number of horses in training, to help identify subclinical pathology (see Figure 117-5). It can also be useful in a horse with recurrent tendonitis, with preexisting ultrasonographic abnormalities, in which it is important to determine if there is inflammation and recurrent injury (Figure 25-2; Color Plate 2).

Fig. 25-2 An advanced event horse with previous history of midbody superficial digital flexor tendonitis of the right forelimb. More recently peritendonous edema had developed distally in the right forelimb. Ultrasonographic images show increased cross-sectional area of the superficial digital flexor tendon, and areas of hyperechogenicity and hypoechogenicity. It was not possible to determine if there was active pathology or if this was the level of healing that had been reached from the previous injury. The palmar thermographic image shows rectangular clip artifacts on both limbs. There is a clinically significant increase in temperature of the distal palmar aspect of the right forelimb compared with the left, indicating inflammation, and thus the image suggests recurrent tendon injury.

Ligaments are more difficult to image. The proximal aspect of the suspensory ligament is positioned deeply, and in my experience there is no characteristic thermal pattern associated with desmitis. The midbody of the suspensory ligament may have increased temperature if it is inflamed, and thermography can be useful to accurately localize inflammation in horses with complex pathology affecting the splint bone and/or suspensory ligament. Active suspensory branch desmitis may be detected thermographically.

The majority of long bones are covered in muscle and cannot be imaged thermographically. However, the dorsal aspect of the third metacarpal bone can be evaluated in horses with sore shins. Thermography may be useful for screening and for grading of severity of injury.2

Muscle inflammation can be identified as areas of increased temperature, although some acute injuries with edema appear cool10 (Figure 25-3; Color Plate 3). This is clinically useful, as the clinical localization of muscle strains can be difficult. Look for a consistent left-right asymmetry.

Fig. 25-3 Three examples of muscle injury. The left thermographic image shows a left gluteal injury with increased heat signature. The middle image shows an increase in heat over the biceps femoris muscle. The right image is of a chronic gluteal injury with fibrosis, which has a cooler thermal pattern.

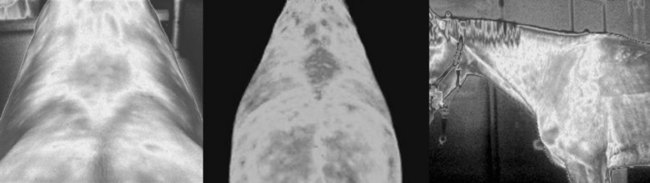

The neck should be bilaterally symmetrical, with care taken that the camera settings are not altered between the two sides. It can be helpful to reevaluate the first side after assessing the contralateral side, to ensure that any differences are genuine. Some horses with cervical pathology have interference with the sympathetic outflow and may show increased superficial blood flow at the affected dermatomes (Figure 25-4; Color Plate 4). The back has a normal, central stripe of increased temperature. Imaging laterally is prone to artifacts, and the images should be obtained as far dorsally as possible from an elevated position behind the horse. Some people image using the reflection from a stainless steel mirror positioned at an angle above the horse. The diagnosis of neck and back lesions is controversial. Some use thermography to guide acupuncture or osteopathic treatment11 and consider that back pain can be a sympathetic associated pain syndrome. I tried sympatheticolytic drugs in a number of horses with back pain and saw improvement neither in the thermographic nor the clinical signs. In my experience thermography can detect areas of back inflammation associated with muscle injuries, impinging dorsal spinous processes, or supraspinous ligament injuries (see Figure 25-4), although the sensitivity and specificity are poor. It may be useful as part of a combined imaging approach. Thermography may also be helpful in assessment of saddle fit.

Fig. 25-4 The left and middle thermographic images are caudodorsal views of the back, showing areas of increased heat associated with clinical signs of back pain and impinging dorsal spinous processes evident radiologically. The lateral view of the neck is from a horse with marked caudal cervical facet joint osteoarthritis. There is an increase in superficial blood flow in this region.

Thermography has also been used to detect methods of counterirritation12 and is being employed by the Fédération Equestre Internationale at competitions as an adjunct to medication control.

Conclusion

Thermographic imaging can be a useful adjunct to a standard lameness and orthopedic evaluation. It requires a considerable investment of time to gain the necessary experience to differentiate between normal variation and patterns suggestive of pathology. Improvements in technology have brought high-quality imaging within the reach of the equine practitioner, which consequently makes image interpretation much easier. A standard protocol for imaging is important for obtaining accurate results, as is critical evaluation of the findings to integrate them into the total clinical picture. Although not necessary in the vast majority of horses with lameness, there are some horses in which thermography can be helpful. It has roles in screening populations of horses in training to pick up early signs of disease.