Chapter 117Lameness in the Three Day Event Horse

Sport of Eventing

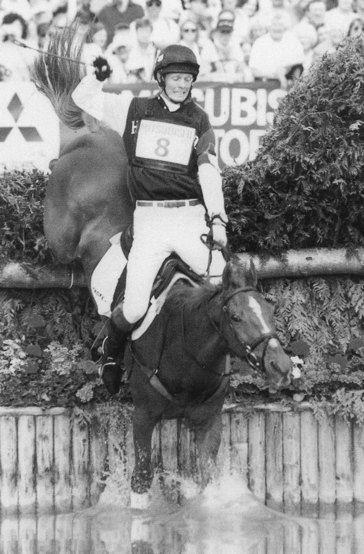

The sport of eventing generally is considered the most all-around test of a horse’s athletic ability, and therefore the horses tend to be jacks-of-all-trades rather than excelling in any one particular area. The competition consists of three disciplines, namely dressage, show jumping, and cross-country, with the latter being the most influential phase. The Three Day Event or Concours Complet International (CCI) is the pinnacle of the sport (Figure 117-1) and is run over 4 days: 2 days of dressage, followed by a day for the speed and endurance phases and a day of show jumping. In the traditional long-format event the speed and endurance test consists of roads and tracks at trotting speed, a steeplechase, and the actual cross-country phase over fixed obstacles. This is a severe athletic test, and horses normally compete in only two or maximally three such competitions in a year. Since 2004 a “short format” Three Day Event has been introduced, which excludes the steeplechase and endurance phases but leaves the cross-country phase. This is cheaper to stage and potentially requires a smaller site on which to run the competition. At CCI**** level the course must be 6720 to 6840 m in length, with up to 45 jumping efforts at an optimum speed of 570 mpm, to therefore be completed within 11 to 12 minutes. It has resulted in some horses competing in three or occasionally four such competitions in one year.

Fig. 117-1 Example of a cross-country fence at CCI**** level.

(Courtesy Kit Houghton Photography, Bridgewater, Somerset, United Kingdom.)

CICs (international One Day Events), One Day Events or Horse Trials, compress the same disciplines into a shorter time frame but without the roads and tracks and steeplechase phases. The distance and thus time for the cross-country phase are also much shorter, and there are fewer jumping efforts, so that many such competitions may be completed in a season. For most advanced horses, One Day Events are used as training for the Three Day Events, although a large number of recreational competitors aspire to compete in only One Day Events. There are an increasing number of relatively high–prize money CICs, encouraging international level horses to compete more frequently. The emphasis of this chapter is the Three Day Event horse, because the extreme demands placed on this horse give characteristic patterns of lameness, whereas the novice One Day Event horse can be considered a standard riding club or recreational horse from a veterinary point of view.

Eventing is an established Olympic sport and a substantial equine industry. The highest grade of competition is the four-star event (CCI****). Traditionally these have been the English events of Badminton and Burghley, although there are now more elite level competitions around the world including Lexington, Kentucky, United States and Lumhulen, Germany. The sport has a high-risk element for rider and horse, and a noticeable recent trend has been to try to make courses safer, with the introduction of fences with frangible pins to try to minimize the frequency of rotational falls.

The sport includes substantial veterinary involvement. During a Three Day Event, the horse is examined by the official veterinarians on arrival, the day before commencing the dressage, before and after the cross-country, and the morning before show jumping. The horse must be deemed fit to compete—that is, the horse must be sound—throughout the competition, and thus any orthopedic disorders are of great clinical significance. A mild degree of hindlimb gait asymmetry may be acceptable to the Inspection Panel, but any noticeable forelimb lameness normally is not permitted.

Horse Types

Because the Three Day Event places great emphasis on the horse’s speed and stamina, there is a preference toward the Thoroughbred (TB) or predominantly TB crossbreeds. A substantial proportion of horses are of uncertain or unknown breeding. Exceptions have been notable, but Warmbloods and classic Irish hunter types normally do not have the endurance required at the top level. Such horses often may do extremely well at the lower levels, however, because they move and jump better than the pure TB. Figure 117-2 demonstrates what could be considered the ideal modern eventing stamp, a highly successful New Zealand TB. A horse’s ability and mental aptitude are the most important determinants, and other body types are successful (Figure 117-3). An average ideal size would be 16.2 hands, but the rules are not hard and fast. The short-format Three Day Event has perhaps slightly reduced the emphasis on pure galloping ability, and because the courses usually have the same number of jumping efforts, sometimes in a shorter course, there is a need for the horses to be quick and nimble.

Fig. 117-2 An ideal modern eventing stamp. This 16.1-hand–high New Zealand Thoroughbred gelding was an individual Olympic and World Championship gold medalist.

(Courtesy Badminton Speciality Feeds, Oakham, Rutland, United Kingdom.)

Fig. 117-3 Example of a successful but tall and hunter-bred horse. This 17-hand–high gelding Thoroughbred-cross Irish draft horse was a Badminton CCI**** winner and Open European Championship Team gold medalist.

(Courtesy Kit Houghton Photography, Bridgewater, Somerset, United Kingdom.)

The financial value of event horses is considerably lower than that of racehorses, show jumpers, or dressage horses, so any horse with outstanding ability in one of these phases is likely to be used in that sport first. If the horses do not succeed, then they may be tried as potential event horses. These horses bring with them any injuries they may have accumulated, but because of the different stresses imposed during eventing, this may not be a problem. For example, event horses tolerate low-grade carpal pathological conditions from previous race training. A small number of horses are bred specifically for eventing. Stallions generally are considered to lack the courage required to compete at the top level, and because the horse takes a number of years to reach its peak, choosing proven sires is a problem. The predominantly TB Irish sports horse and the relatively larger-boned New Zealand and Australian TBs are sought after.

Event horses normally commence dressage and show jumping training at 4 years of age and start competing in prenovice and novice One Day Events from the age of 5. Depending on the horse’s ability and rider’s skill and patience, a horse usually competes in its first (graded as a CCI* or CCI**) Three Day Event at 6 to 7 years of age. A substantial proportion of horses do not have the ability, courage, or physical durability to proceed beyond the CCI** or CCI*** level to the top grade of CCI****.

Influence of the Sport on Lameness

Event horses are generally skeletally mature when they commence training and are not trained at the same speed or intensity as racehorses. They therefore have different patterns of injury, although most of the problems are still related to training. Primary long bone pathological conditions are rare. Soft tissue injuries such as tendonitis are common and often career limiting. The amount of endurance training necessary produces repeated cyclic loading, and problems such as osteoarthritis (OA) are common. The other subset of event horse injuries is acute traumatic injuries sustained during competition. Because the horses are jumping large fixed obstacles at speed, they are prone to falls and to direct traumatic fractures. The short format does not seem to have led to a dramatic difference in the type or incidence of injuries. Horses may tolerate low-grade soft injuries better than with the long format, and in the long run there might be a decrease in the incidence of injuries.

Fence design has changed in recent years. Square-shaped fences are avoided, and rounded top contours are now more common. These fences give horses more leeway to correct mistakes and cause less severe direct impact trauma. The fences may be 1.2 to 1.4 m high, with a 2-m spread and a 2-m drop, so substantial strain can be placed on the supporting structures of the limbs on landing. The quality of the terrain also appears to have an important impact on the incidence of lameness problems. The competitions are run predominantly on turf, the nature of which depends on the soil type, local weather, and management factors. At the lower level, financial constraints generally preclude much improvement on the quality of the ground, but some of the top events try to maintain a permanent track that is tended carefully.

The prolonged period and intensity of training required for horses to reach an elite level means that those horses not metabolically or physically suited to the sport are selected out. For instance, few elite horses have recurrent exertional rhabdomyolysis or navicular syndrome. Three Day Events are regulated by the Fédération Équestre Internationale. A strict medication control program is enforced and permits only emergency medication at the competition after official veterinary approval or the use of a small number of permitted forms of medication, including antibiotics, rehydration fluids, and preparations for treating gastric ulcers.

Training Methods

Event horses train in all three disciplines, with the actual methods varying greatly among riders. A complete description of training methods is available elsewhere.1 Most competing horses have natural cross-country ability, so little time generally is spent on training for this, because the progression of competitions provides sufficient experience. Event horses normally are selected for natural jumping action, but jumping technique during the cross-country phase is different from that needed for show jumping. Therefore event horses may not be as careful when show jumping and can have a tendency to touch poles. Most event horses are show jumped regularly, especially during the off season. The event horse’s weakest link is usually the dressage phase. The movements required are no more than a medium level of pure dressage, but the different breeding and level of fitness of these horses means that the major challenge can be to control the horse’s temperament. Most of the skills training revolves around dressage, and a high standard now is required to be competitive at the top level.

Fitness training is a major component of the preparation for a Three Day Event and is where most orthopedic damage is incurred. The horse is likely to undergo a 3- to 4-month training period for the target Three Day Event. Training methods vary greatly among riders and often depend on local factors such as the availability of hills for trotting or all-weather gallops. Restricting the horse to training solely on an artificial surface is not advisable, because this seems to predispose the horse to injury when the horse actually competes on a natural surface.

Event horses normally receive a 6-week initial period of walking and trotting on the roads, and then commence cantering exercise. Different riders vary in their use of conventional or interval training but usually peak the quantity of work at around three canters of 8 minutes, or shorter if a hill is available. The quality of the work usually is increased closer to the Three Day Event to include faster work. One Day Events are used to monitor the horse’s fitness and as additional training. The dressage and jumping training also substantially contributes to the fitness regimen. Older, experienced horses can get to major competitions with relatively few preparatory runs in comparison with less experienced horses, making it easier to manage low-grade injuries.

The majority of riders have not substantially reduced the intensity of their training for short-format competitions. The initial impression was that horses were finishing short-format competitions more tired than at a long-format competition. This was unexpected because of the lower overall effort of the shorter format. It may have been a result of the more intense nature of jumping the same number of fences in a shorter course. There may also have been an element of riders not preparing their horses as intensively for what was thought to be a less demanding competition. A study comparing cross-country recovery rates at a CCI** in long and short formats showed no significant difference between the two groups.2

Conformation and Lameness

Although the horse’s stamp may vary the basic conformation must be correct. Eventing is unforgiving to conformational defects compared with show jumping and dressage. The general principles are the same as for any equine athlete. Serious conformational defects include being back at the knee, having upright pasterns and hocks, and having a moderate or severe toed-out conformation. Of slightly lesser importance are having a long or short back, being over at the knee, or having long, sloping pasterns. Defects such as offset knees and a slight-to-moderate toed-in conformation seem to be less important. A good foot conformation is always desirable, but many event horses have the TB trait of weak feet with collapsed heels.

The prepurchase examination for a young event prospect with hopes of a Three Day Eventing career is likely to be strict. The conformation should be assessed critically at this stage. Although the horse may have sufficient talent, defects in conformation may not allow it to stand up to the 5 or so years of training necessary to reach the top level of the sport. Conversely, it is possible to be more lenient in the interpretation of subtle problems when performing a prepurchase examination on an older, experienced horse. The horse’s competitive record should be assessed carefully, because advanced horses are likely to have accumulated wear-and-tear changes during an extended career. Any conformational or subtle soundness queries can be addressed in light of the horse’s proven ability to perform its task.

Clinical History

A routine lameness history should be obtained, emphasizing and obtaining the following information:

Lameness Examination

My standard approach is described, and the regions requiring particular attention and the most rewarding procedures are outlined for horses with subacute or chronic lameness problems. Care should be taken to palpate all limbs and the back thoroughly, because many concurrent or compensatory injuries can be found that way. Because many problems are subtle, the horse should be examined on a variety of surfaces and at different gaits.

Particular attention should be paid to the feet. The size, shape, and conformation should be assessed in relation to the size and breed of horse. The suitability of the shoe type for that horse should be determined, because farrier preference may have been influenced by fashion. The fit of the shoe should be correlated with stage in the shoeing cycle. Fortunately, the trend is to move away from the traditional problem of shoeing the horse short and tight at the heel. The hoof should be palpated for heat and any cracks or defects. The sole should be pared and hoof testers carefully applied over the entire solar surface, assessing the solar compliance and any pain response. Horses with recurrent bruising associated with soft soles may not have demonstrable pain on examination, but the lack of solar rigidity is clearly evident. Percussion may be helpful in a small proportion of horses. An increased digital pulse amplitude can be helpful in determining the presence of any inflammation in the foot and is especially important if the amplitude is asymmetrical in a limb or between feet. A subtle increase in digital pulse amplitude is best evaluated after trotting the horse in hand on a hard surface.

The horse should be palpated carefully for distention of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) and metacarpophalangeal or metatarsophalangeal (fetlock) joint capsules. The range of joint flexion and any resentment to flexion should be assessed carefully. Particular attention should be paid to the palmar metacarpal structures for presence of subtle, diffuse filling and any discrete swelling, heat, or pain in the tendonous or ligamentous structures. Owners and riders of event horses tend to be thorough in their own palpation of this region and often know the normal contours of their horse well. However, they often are misled by distention of the medial palmar vein or diffuse swelling from a more distal inflammatory lesion.

In the hindlimbs, pain on palpation over the cunean bursa and in response to the Churchill test should be determined. The medial femorotibial and femoropatellar joint capsules should be palpated to detect distention. The muscle tension in the back and hindquarters should be assessed carefully. Trigger points and painful foci should be determined, and the range of spinal flexibility in response to running a blunt object along the back should be assessed.

During the static examination the horse should be assessed for symmetry. The horse’s condition and degree of muscling should be assessed in relation to its level of fitness. The freeness of stride, dynamic foot placement, and foot flight arcs should be assessed at the walk. At the trot any head nod and the range of gluteal excursion should be assessed to determine any lameness. Lunging in a circle on a hard surface frequently is used to exacerbate subtle lameness. However, it is also critical to see the horse lunged on a soft surface, a portion of the lameness examination that often is omitted. Different lameness conditions may be evident on different surfaces, and this comparison is valuable. For instance, a horse may have a low-grade concussive distal limb lameness evident when lunged on the hard surface. However, the primary problem may be proximal suspensory desmitis (PSD), pain from which is evident only when the horse is lunged on a soft surface. Notwithstanding the value of evaluating all the lameness problems present, many of these horses have numerous, low-grade sites of pathological conditions to which they have adapted. Evaluating these can be a frustrating business, and it is important to determine the current problem noticed by a knowledgeable owner or rider. Event horses are often remarkably tolerant of low-grade pain to which they become accommodated compared with dressage horses. Evaluation of the horse while the horse is being ridden can be more difficult, but this form of movement can exacerbate low-grade lameness. Riding may be the only way of observing problems evident during certain movements, such as lack of hindlimb impulsion during a change of gait or when jumping. Seeing the horse ridden by a different, preferably more experienced rider can be helpful in some horses suspected of having back pain or when schooling or behavioral problems are present.

Determining the normal range of soundness is a difficult and contentious issue. Because of age and level of work, most top-level event horses have some degree of orthopedic pathological condition. I prefer to score lameness on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being sound and 10 being non–weight bearing. An advanced horse should be sound in the forelimbs when trotted in a straight line, but a large proportion demonstrate a 1 of 10 bilateral forelimb lameness when trotted in a circle on a hard surface. Some horses that are competing satisfactorily may show a greater degree of symmetrical lameness, but asymmetry in lameness may indicate that an important problem exists. Advanced horses can demonstrate up to a 2 of 10 hindlimb lameness when trotted in a straight line, without being penalized for this in a trot-up at a Three Day Event. Many have a 2 to 3 of 10 bilateral hindlimb lameness while circling on a hard surface. Hindlimb lameness evident on soft surfaces is likely to produce lower dressage scores, because the horse will exhibit poor and asymmetrical action.

Flexion tests are useful to exacerbate any subtle lameness problems, but these tests are not specific. Flexion tests can be particularly helpful in evaluating horses with lameness evident only immediately after they have completed an event. These horses can be frustrating, because they are often clinically sound when evaluated subsequently. A persistent positive response to flexion that can be alleviated by diagnostic analgesic techniques is important. Limb protraction, retraction, adduction, and abduction can be helpful in exacerbating upper-limb pain. Turning the horse in a tight circle can be used to assess coordination and flexibility. The range of cervical movement is assessed by observing the horse reach for food (voluntary movement) and by manual manipulation (forced movement). Many horses can cheat and reach the flank by rotation of the upper cervical region, rather than by full lateral flexion of the entire neck.

Different considerations apply when examining the horse with a history of an acute, severe lameness, usually after the cross-country phase of a competition. A comprehensive evaluation of an acutely lame horse must be performed (see Chapter 13) and is described in detail elsewhere.3 Unfortunately, localizing signs may be minimal, the horse may be in cardiovascular shock, and initial efforts must be directed at providing support to the horse and the suspected region of injury. Fractures are caused most commonly by external trauma. Particular attention should be paid to the shoulder region for signs of fracture of the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula and to the stifle for effusion or periarticular swelling associated with patellar or other fractures. Soft tissue injuries such as severe suspensory desmitis or superficial digital flexor (SDF) tendonitis may cause acute, severe lameness.

Diagnostic Analgesia

Diagnostic analgesia is an important tool in lameness diagnosis in event horses. Because the horse may have many palpable abnormalities, differential diagnosis is important. However, no localizing clinical signs may be apparent, and diagnostic analgesia is critical to identifying the painful region. Specific treatment can be given if a problem is identified accurately. A positive response to intraarticular analgesia usually means a horse is likely to respond to intraarticular medication, leading to a quicker return to work. In horses with lameness problems too subtle for accurate interpretation of diagnostic blocks, intraarticular administration of corticosteroids may be useful to assess the long-term response to treatment. Even with experienced riders this method of management can have a placebo effect, because the rider may desire for the problem to be veterinary rather than from schooling.

Perineural and intrasynovial analgesic techniques are used commonly. Intraarticular analgesia is particularly helpful because many problems are joint related, and a quick and definitive diagnosis can be achieved. Owners greatly resist clipping of the hair during the competition season, and clipping is not necessary in fine-coated animals if a thorough scrub is performed. The preferred techniques for the most commonly performed blocks are described subsequently.

The palmar digital nerve block should be performed as far distal as possible, angling the needle axially and distally to the cartilages of the foot. Separate medial and lateral blocks may be helpful to localize the pain to a specific heel. Blocking the palmar nerves at the level of the fetlock is less likely to desensitize the fetlock joint with a block performed just below the base of the proximal sesamoid bones (PSBs), rather than at the level of the PSBs. The palmar portion of a low four-point block should be performed just proximal to the digital flexor tendon sheath (DFTS) to decrease the risk of proximal migration of local anesthetic solution, taking care to go above or below the communicating branch of the palmar nerves. The lateral palmar nerve block is a satisfactory method of achieving proximal palmar metacarpal analgesia. Because the middle carpal joint is not a likely source of pain in event horses, the risk of confusing pain from this site with that from the origin of the suspensory ligament is minimal.

The DIP joint is injected most easily at a site on the dorsal midline, using a vertically directed needle. Six milliliters or less of local anesthetic solution should be used to decrease the risk of diffusion from the joint. For the fetlock joints I prefer the lateral sesamoidean ligament approach because most horses do not have gross joint distention and the fixed anatomy of this approach is reliable.

In the hindlimbs the DIP, proximal interphalangeal, and metatarsophalangeal joints often are overlooked sources of pain. Perineural analgesia normally starts with plantar blocks performed at the base of the PSBs, followed by a low six-point block if necessary. Analgesia of the proximal plantar metatarsal region can be performed most easily by blocking the lateral plantar nerve 1 cm distal to the tarsometatarsal (TMT) joint. This blocks the nerve before it branches into the plantar metatarsal nerves and carries a minimal risk of inadvertent penetration of the distoplantar outpouchings of the TMT joint capsule.

Imaging Considerations

Radiography

Radiography is the mainstay of imaging, but a few special considerations are necessary in event horses. Lateromedial and dorsopalmar radiographs of the digit can be helpful in assessing foot balance. The palmaroproximal-palmarodistal oblique image often is underused in assessing subtle pathological conditions of the navicular bone and the palmar processes of the distal phalanx. Some fractures of the distal phalanx are only detectable in this radiographic image. The flexed cranioproximal-craniodistal image of the stifle is especially valuable for assessing the medial aspect of the patella for fractures. It is important to angle the x-ray beam so that the trochlear ridges are not superimposed over the patella, because some fractures or evidence of comminution may otherwise be obscured. A relatively underexposed and undercollimated lateromedial image is also beneficial to detect small, displaced fragments, which otherwise may be missed.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonographic evaluation of the palmar metacarpal structures is a vital part of the lameness evaluation of an event horse. SDF tendonitis is a common and career-threatening injury, and if the veterinarian has any doubt about even a subtle problem, an ultrasonographic examination should be performed. Even when primary forelimb lameness is located at a distal site, the most important lesion may be a compensatory tendonitis in the contralateral limb.

It is usually not necessary to clip the coat, particularly if the hair is fine, and diagnostic images can be obtained after thorough scrubbing and the liberal application of alcohol and gel. The coat may be clipped to obtain maximal detail if subtle tendonitis needs to be investigated. Clients are often reluctant to have the coat clipped for a precautionary scan during the competitive season, because they perceive that the horse will be flagged as having a problem when it next competes. In my experience, sufficient detail is visible in fine-coated horses without clipping, although the clients are warned that greater image quality can be obtained with clipping, and if the image quality is nondiagnostic, the coat needs to be clipped. Often the difficulty is not in identifying abnormalities within the tendon but in determining the relevance of any changes that are present. Many advanced horses have changes in fiber pattern of the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT). Transverse and longitudinal views should be obtained in a systematic fashion. Different focus, gain, and frequency settings optimize evaluation of different structures. The cross-sectional area (CSA) of the SDFT should be obtained routinely, because sequential monitoring of this may allow the early detection of tendonitis. Determining the CSA also assists in assessing the current importance of chronic lesions, which is an important and helpful part of the ultrasonographic examination and should not be omitted.

Ultrasonography also can be helpful in assessing articular and periarticular pathological conditions in structures such as the patellar ligaments. Examination of the ventral sacroiliac ligaments per rectum also can be valuable when pain in this region is suspected.

Scintigraphy

Nuclear scintigraphy is a useful technique for evaluating some lame event horses. Scintigraphy commonly is used in horses with hindlimb lameness, back problems, multiple limb lameness, and forelimb lameness with an equivocal or negative response to diagnostic analgesia. Image quality can be a concern, because event horses are skeletally mature and the degree of pathological bone conditions is low. Normal bone uptake can be limited, except in horses with acute trauma. Good technique is therefore essential to obtain diagnostic images, and postprocessing techniques, such as using motion-correction software, can be helpful. Case selection is also important, because the more chronic and low-grade the problem, the lower the likelihood of finding an obvious focal region of increased radiopharmaceutical uptake (IRU). Examples of conditions for which scintigraphy can be rewarding include nonlocalized foot pain (pedal osteitis and insertional injury of the deep digital flexor tendon [DDFT] attachment), stress fractures (although these are rare overall), and OA of the thoracolumbar synovial articulations (facet joints).

Normal scintigraphic patterns are described elsewhere.4 Regions that commonly have greater radiopharmaceutical (RU) than elsewhere in event horses, but without associated pathological conditions, include the distal phalanx, the subchondral bone of the proximal interphalangeal joint, the subchondral bone of the fifth and sixth cervical and sixth and seventh cervical articulations, and the distal tarsal bones. The distal aspect of the tarsus appears to have active bone remodeling when evaluated scintigraphically, but many event horses do not show lameness or a positive response to either flexion tests or local analgesia. In a study evaluating the accuracy of scintigraphy in horses with confirmed distal hock joint pain, we found a positive predictive value of 0.70 and a negative predictive value of 0.91 for focal IRU.5 Because of this high false-positive rate, scintigraphy should be used with thorough clinical examination. Although relying on scintigraphy in fractious horses may be tempting, authenticating the diagnosis using diagnostic analgesia is important.

Thermography

Thermography has been used for more than 30 years but is still a developing diagnostic modality. The technology has improved recently, and thermography units are now affordable. The handheld infrared imaging cameras are particularly attractive. Thermographic imaging provides a sensitive representation of skin surface temperature, but many confounding variables make interpretation of these images difficult. To develop expertise involves a steep learning curve, and considerable amounts of time and experience are necessary to make consistently useful interpretations. Major advantages include that the technique is noninvasive and is performed quickly. Thermography is similar to scintigraphy because it is a physiological rather than an anatomical imaging technique. Given the high prevalence and importance of soft tissue injuries in event horses, thermography has applications in detection and in monitoring response to therapy. Because of low specificity, however, thermography should be used with other imaging techniques.

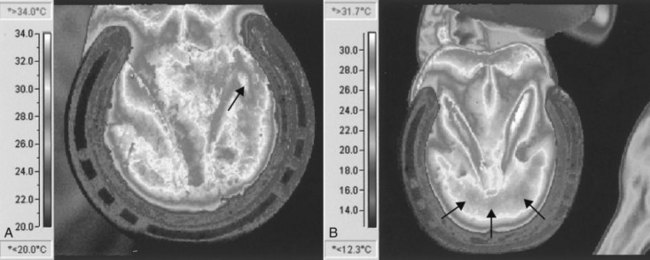

Thermographic imaging is useful in evaluating foot balance and in differentiating various types of inflammation of the foot (Figure 117-4; Color Plate 10). Examinations before and after exercise are particularly useful for this purpose. Similarly, preexercise and postexercise thermograms are helpful in identifying specific superficial muscle injuries. Accurate identification of local muscle strain permits treatment to be focused on the affected area, with a consequently shortened convalescent period. Thermography is also a useful tool in evaluating neck and back problems, although interpretation is more complex in these regions.

Fig. 117-4 Examples of different thermographic foot patterns (solar images). A, This horse has a medial corn, manifested as a focal hot spot (white) (arrow) within an area of increased temperature. B, This horse has subacute laminitis, with a pattern of increased heat in the region of the tip of the distal phalanx (arrows).

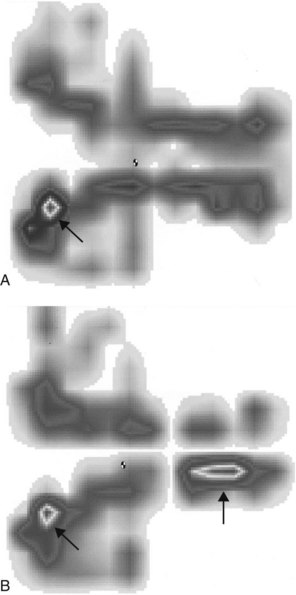

Thermography can be particularly useful in monitoring SDF tendonitis and can be used as part of a routine screening procedure, with regular examinations in the run up to a Three Day Event. Thermography can detect small lesions before clinical signs are evident, or it can be helpful in determining if a chronic lesion is active (Figure 117-5; Color Plate 11). If thermography suggests a lesion is present, then ultrasonographic examination is indicated. During the convalescent phase after injury, regular thermographic screening allows detection of any signs of inflammation in the affected region, as the plane of exercise is increased. Care must be taken to avoid artifacts from bandaging, previous clipping, and topical medication.

Fig. 117-5 Palmar thermographic image and subsequent transverse (on the left) and longitudinal ultrasonographic images of the metacarpal region of an advanced event horse 10 days after successfully completing a Three Day Event. The horse was having a routine examination, and no clinical localizing signs were evident in the tendon. The thermogram (top) demonstrates a focal hot spot over the distal aspect of the left superficial digital flexor tendon (arrow), and the ultrasonographic images reveal a hypoechogenic core lesion in the same region.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The increased availability and use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have revolutionized the diagnosis and management of foot lameness in recent years. Diagnostic images can now be obtained in a standing horse, without the risk and expense of general anesthesia. This imaging modality is thus much more likely to be used early in the investigation of a lameness problem (see Chapter 21). In horses with foot lameness with no clinically significant radiological signs nor obvious superficial inflammation or pain, MRI can be helpful. Even if there are no relevant findings, the horse can be managed with corrective farriery and a relatively early return to exercise once the lameness has subsided, with a greater degree of confidence that there is not an underlying soft tissue injury that will be adversely affected. It can also be helpful in assessing the degree of activity of ultrasonographic findings in more proximal soft tissues, and indeed in detecting lesions that are not evident ultrasonographically. Evidence of bone trauma may be detected that is not radiologically apparent.

Saddle Pressure Analysis

Computerized saddle pressure analysis using a force-sensing array system allows an objective assessment of pressure distribution beneath the saddle (Figure 117-6; Color Plate 12). Poor saddle fit is an important problem in event horses and is discussed elsewhere in greater detail (see page 1132). Computerized saddle pressure analysis is straightforward to perform and is complementary to conventional saddle fitting. By allowing an objective assessment, computerized saddle pressure analysis can be useful to confirm a problem to a rider, owner, or saddler. The better systems allow dynamic assessment of saddle fit at exercise, which is not otherwise possible.

Fig. 117-6 Computerized saddle pressure analysis images. Cranial is to the left, and left is to the bottom. A, This image shows a poorly fitting saddle, with a focal pressure point in the left wither region (arrow). B, This image demonstrates failure of a gel pad to alleviate the pressure point and the development of an additional pressure point caudally (arrows).

Proceeding without a Diagnosis

Although a diagnosis can be made in most lame event horses, factors such as the experience level of the veterinarian, the thoroughness of the lameness workup, the number of imaging modalities available, and the nature, severity, and stage of the disease process affect diagnostic ability. If a horse is seen repeatedly on a first-opinion basis, stepping back and reassessing the horse as if from the start is sometimes necessary. It may be necessary to refer the horse for a second opinion or for advanced imaging techniques, such as scintigraphy, if these have not been performed. In some horses the precise diagnosis continues to remain elusive. In horses with obscure forelimb lameness, I routinely perform an ultrasonographic examination of the palmar metacarpal soft tissue structures, because tendonitis and desmitis are important and highly prevalent. Serial CSA measurements of the SDFTs should be obtained, because the most relevant problem with an undiagnosed low-grade lameness may be a compensatory tendonitis in another limb. Any evidence of tendonitis indicates that exercise level should be decreased. Similarly, any persistent clinical signs of swelling in the palmar metacarpal structures should prompt a cautious approach. Even in the absence of ultrasonographic changes, mild swelling should alert the veterinarian to the possibility of a subclinical problem with tendonitis or desmitis. It is important not to rely too much on ultrasonography for diagnosis of soft tissue injuries, because early lesions may not be apparent.

Generally in horses with low-grade, undiagnosed lameness the response to a period (a few days to weeks) of rest should be assessed. If the response is poor, then most horses with an undiagnosed, low-grade hindlimb lameness can be continued in work, with or without the use of a systemic nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) such as phenylbutazone. Greater caution normally is advised in horses with undiagnosed forelimb lameness, because the risk of developing a career-limiting injury with continued exercise is greater compared with similar injuries in the hindlimbs. If a subtle problem persists, then it may be necessary to increase exercise intensity to exacerbate the problem to a point at which diagnostic local analgesia can be performed. If a competition is imminent, the owner or rider may apply considerable pressure to treat the most likely problem in the hope of rendering the horse sufficiently sound to compete.

If lameness is severe without initial diagnosis, then the horse should be given box rest, and the workup should be repeated until a diagnosis is achieved. If an upper limb soft tissue problem or a back problem is suspected, then a physiotherapeutic, chiropractic, or osteopathic opinion can be helpful. Although veterinary opinion is divided on the validity and value of these techniques, an owner frustrated by the lack of a veterinary diagnosis is likely to turn to these. Horses with poor performance may have schooling or behavioral problems. Assessment by an experienced and different rider can be helpful.

Shoeing Considerations

Foot problems are a major problem in event horses, and the importance of high-quality farriery in minimizing the incidence of lameness cannot be overemphasized. Regular and good farriery is critical in maintaining good medial-to-lateral and dorsal-to-palmar (plantar) hoof balance. Types of shoes vary among the traditional fullered hunter-type shoes, continental flat shoes, four-point style shoes, and various types of bar shoes. For routine shoeing the conventional fullered shoe offers the advantage of superior grip. Many farriers prefer the extra width of the flat section shoe, because this shoe is easier to fit, has sufficient width at the heel, and gives extra sole cover. If not applied correctly, flat-section shoes may cause excessive sole pressure in horses with flat feet. Traction devices are necessary if flat section shoes are put on horses working on tarmac. Natural balance shoeing has become popular recently in event horses, but although the technique suits some horses, others may actually develop lameness because of improper shoeing technique. However, the natural balance concept of a more palmar location for the breakover point has been well accepted. Seeing horses shod with the shoe set well back is now common, and quarter clips rather than toe clips are most common. This is helpful in horses with long-toe conformation, OA of the DIP joint, or navicular syndrome. A rolled-toe shoe may give a similar effect, although bringing the breakover point back to the same degree is difficult, and care must be taken to set the shoe back sufficiently.

The most common therapeutic shoe used in event horses is the bar shoe. The egg bar shoe is used commonly to manage horses with navicular syndrome and other causes of palmar foot pain and to provide support in horses with a collapsed heel. Egg bar shoes are heavy if they protrude beyond the heel bulbs and may be pulled off. Shoe loss is an important issue in event horses, more so than in other sports horses. As a compromise the straight bar shoe may provide additional foot stability while reducing the risk of shoe loss. In horses that require egg bar shoes, overreach boots can be used to reduce the risk of shoe loss, and by using a more palmar point of breakover, the front feet may leave the ground more quickly compared with horses with conventional shoes. In horses with a weak heel or quarter, laminar separation, or focal osteitis of the distal phalanx, an egg bar shoe may provide inadequate support and a heart bar shoe can be beneficial. This shoe is heavy, does not project as far beyond the heel as does the egg bar shoe, and transfers some portion of weight-bearing load to the frog. In horses with pain localized to one heel bulb or quarter, a half bar shoe can provide sufficient support and is lighter than a full heart bar shoe.

Pads are used relatively infrequently in event horses. Although pads may provide short-term benefit in horses with sole pain, they promote excess movement of the clenches and premature shoe loosening. Full pads cause a poor microenvironment of the foot. Packing the soles of the hoof has become popular in recent years because it is thought to protect the soles and to have anticoncussive effects, but without the risk of premature shoe loosening. Modern synthetic hoof repair materials can be beneficial in horses that have lost portions of the hoof wall, because the defect can be filled and shoe nails can be placed subsequently. However, routine use of hoof repair materials to augment hoof wall in horses with poor-quality, cracking, and flaking feet should be discouraged and may even cause the problem to persist. If used, repair material should be removed at the end of the season, and the horse should be turned out without shoes. The foot may break up initially but will grow back stronger without the repair materials.

Steel shoes are used routinely, but some riders switch to aluminum shoes at a Three Day Event. The foot must be of sufficient quality to cope with the lower degree of support offered by the more flexible aluminum shoe, and switching is not recommended if the horse has any history of foot-related lameness. Any speed and recovery benefits of the lighter shoes do not appear to be obvious in event horses. Synthetic shoes rarely are used.

Road nails or studs often are used, especially in broad section shoes, to decrease the risk of slipping on the roads during walking and trotting exercise. Improper use of road nails or studs may cause hoof imbalance. If the grip point is positioned near the middle of the foot (rather than near the heel), the foot may rock over this point during weight bearing. Event horses commonly wear studs for competition. Some advocate that a single stud be worn simply on the basis that if the stud is on the outside, the risk of the horse treading on itself is less. With a single stud, the foot can still twist, causing less jarring to the limb overall. Conversely, a single stud severely imbalances the foot, and because the roads and tracks phase of a long-format Three Day Event often includes sections of metaled road or tracks, this could induce excessive strain on the joints (Figure 117-7). Studs should be avoided for the roads and tracks phase if logistically possible. However, some horses will jump with confidence only if two or more studs per foot are applied. The studs always should be chosen based on ground conditions, and a blunt inside stud decreases problems from tread injury. Care should be taken to avoid positioning a stud hole over an area of defective hoof wall. Horses are normally reshod 1 week before a Three Day Event, because if a horse is pricked or any foot soreness occurs after shoeing, the horse has time for recovery.

Tack Considerations

Saddle fit is of great importance in event horses. Injuries to the withers and back may manifest as poor performance in the dressage or show jumping phases of competition. Different saddles are required for the different disciplines of eventing, predisposing the horse to fitting problems. The fit of the saddle to the horse is sometimes a secondary consideration to riders, who may have a particular saddle in which they feel secure. Event horses often have high withers, and fitting a saddle is often difficult. Saddle fit can be affected adversely by the tendency of event horses to lose weight dramatically in the run up to a Three Day Event. Therefore a saddle that is fitted 2 weeks before an event can sit too low by competition time. Unfortunately, the use of pads and numnahs to correct poor saddle fit is not effective. Computerized saddle pressure analysis has shown that even gel pads are ineffective in alleviating focal pressure points, and that numnahs and pads placed beneath well-fitting saddles can be detrimental (see Figure 117-6).6 Thick or numerous pads elevate the saddle and put pressure on the midline and over the dorsal spinous processes, a situation that impedes spinal flexibility.

Opinions vary on the benefits of protective leg wear. Tendon boots are used almost universally for the cross-country phase, because the risk of direct traumatic injury to the distal aspect of the limb is high. However, the additional insulation increases the temperature of the distal aspect of the limb. There are theoretical concerns that elevation in temperature could damage tenocytes and predispose the horse to tendonitis, although no clinical evidence indicates that this occurs. Some boots have reinforced sections to give additional protection against speedy cut injuries to the palmar aspect of the tendons, but the large rigid section may rub against the tendons at exercise and cause abrasions. Conversely, some of the flimsy boots do not give sufficient protection against this kind of laceration. Bandages give a greater degree of conformity, but they are more difficult to apply correctly and require inclusion of a reinforcing layer if they are to provide substantial protection. Neither bandages nor boots reduce risk of tendon strain but simply protect against direct trauma.

Ten Most Common Lameness Conditions

Some conditions are more common during training, and others are more common at competitions. The overall prevalence is as follows:

Diagnosis and Management of Lameness

Thoracolumbar and Cervical Soreness and Restriction

Neck and back soreness are common clinical findings in event horses, although they do not always limit performance. Soreness may be secondary to lameness as occurs, for example, when pain on palpation of the brachiocephalicus muscle is found in horses with distally located forelimb lameness. Primary problems may be subtle, and determining the importance of clinical findings can be difficult. To know an individual horse’s normal degree of sensitivity and flexibility can be extremely helpful, because any changes can be correlated with the onset of a performance problem. Questioning a knowledgeable owner, groom, or physiotherapist can be helpful. Sometimes the clinical significance of any soreness can be assessed only by the horse’s response to treatment.

Event horses are particularly prone to muscle soreness when exercise intensity is varied or increased. Intense dressage training initially causes a transient period of lumbar muscle soreness, especially during the sitting trot. Areas of focal pain and muscle spasm may be easily palpable, but assessing flexibility and range of movement is also important. Radiographs are not helpful in diagnosing the relevance of dorsal spinous process impingement, and clinical signs, scintigraphic examination, and a positive response to local analgesia or treatment are necessary to confirm if a lesion is active and/or causing pain. Ultrasonographic examination can be helpful in diagnosing supraspinous ligament injury. Thermography is helpful in detecting acute soft tissue injuries in the thoracolumbar region (see Chapter 25).

Many horses with neck and back pain respond well to physiotherapy. If range of movement is decreased, then mobilization of the affected region is beneficial (see Chapters 93 to 95), which then can be followed by continued stretching exercises, performed by the owner or rider. Massage is beneficial but yields only temporary improvement. Various modalities such as laser, therapeutic ultrasound, and neuromuscular stimulation can be helpful. Results with extracorporeal shock wave therapy have been encouraging in some horses. In some horses, chiropractic manipulation is beneficial. Acupuncture also can be effective if performed by an experienced practitioner. Given the range of physiotherapeutic treatment options available, the degree of experience necessary for optimal treatment results, and the nature of these therapeutic modalities, I suggest that veterinarians work with an experienced and qualified therapist. It behooves the veterinarian to be familiar with these techniques, because case selection and palpation skills can improve.

Horses with caudal cervical restriction caused by OA of the synovial articulations (articular facet joints) may show a positive response to intraarticular medication with triamcinolone acetonide (5 mg) injected under ultrasonographic guidance. Each affected facet joint is injected, and the horse is rested for 2 weeks, after which time improvement is normally dramatic. Horses with mild to moderate impingement of the thoracic dorsal spinous processes can be treated successfully using local injection of methylprednisolone acetate (40 mg) and Sarapin (6 mL). The horse is lunged or long reined for 2 weeks and then returned to exercise. The duration of effect can be as short as 6 weeks, but in a large proportion of horses, the problem resolves without repeat medication. Marks provides a review of the various veterinary options in treating back pain.7 The importance of management and riding factors in treating these conditions cannot be overemphasized. Rehabilitation and reschooling of horses with moderate-to-severe pain are necessary to build up the local musculature and to develop flexibility.

Foot Soreness (Bruising, Imbalance, and Nail Bind)

Foot soreness is a common clinical problem in event horses. Transient sole bruising is frequent, especially in flat- and thin-soled horses. Foot imbalance predisposes horses to soreness, and medial-to-lateral hoof imbalance is commonly present. In horses with a collapsed heel, pain to hoof testers and corns are commonly found. Horses with persistent foot lameness may have laminar separation or focal osteitis of the distal phalanx, and scintigraphy is helpful in differential diagnosis. Poor foot conformation in many horses can predispose them to nail bind or pricking when shod. Shoes often are pulled off, which can lead to breakup of the wall and further problems with shoe security. Regular, high-quality farriery is more important in maintaining good hoof quality than is the feeding of supplements or use of topical applications. Good stable hygiene is also important. Shoeing aspects have been discussed (see page 1131).

Osteoarthritis

Distal limb joints are especially prone to traumatic joint disease, especially in the forelimb. OA of the DIP joint is most common, followed by that of the metacarpophalangeal joint. OA of the proximal interphalangeal joint is rare. Diagnosis is confirmed by observing a positive response to intraarticular analgesia, effusion or fibrosis, a positive response to flexion, and low-viscosity synovial fluid. Radiographs are often unremarkable in horses with early or low-grade OA. Response to intraarticular medication is normally excellent. Combining hyaluronan with a low dose of corticosteroid such as triamcinolone acetonide (5 mg) produces the greatest therapeutic effect. Hyaluronan alone produces an inconsistent response, and low doses of triamcinolone acetonide have been shown to be chondroprotective. Medium-viscosity hyaluronan usually is used initially based on economic factors, but high-molecular-weight products may give a greater effect in some horses. Systemic administration of hyaluronan (intravenously) or polysulfated glycosaminoglycan (intramuscularly) is not nearly as effective as is specific intraarticular medication. Systemic medication does not carry the same risk of iatrogenic infection and is easier to administer and so is used frequently as an adjunct therapy. Prophylactic use of systemic therapy frequently is used in horses in the run up to a Three Day Event or to manage those with pathological conditions of numerous joints or generalized stiffness. Feeding of nutraceuticals such as chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine is also common practice. Although in vitro evidence of efficacy is substantial, no convincing clinical studies demonstrate efficacy in vivo. In fact, studies have demonstrated a lack of oral absorption of chondroitin sulfate8-10 and glucosamine10 in horses.

In horses with OA of the DIP and metacarpophalangeal joints that has been unresponsive to medication, and especially with radiological evidence of osteochondral fragmentation, arthroscopic evaluation can be beneficial. Focal areas of cartilage and subchondral bone damage may be identified, and the horse often responds positively to debridement. Access is limited in the DIP joint, but lesions often are found on the extensor process of the distal phalanx.

OA of the TMT and centrodistal joints is not infrequent, but the distal tarsal joints show scintigraphic evidence of remodeling even in normal event horses. Horses with authentic OA of these joints usually respond well to medication with low doses of long-acting corticosteroids (40 mg of methylprednisolone acetate). The condition rarely seems to progress sufficiently to necessitate chemical or surgical arthrodesis.

Superficial Digital Flexor Tendonitis

Although not the commonest lameness problem in event horses, tendonitis is the most substantial cause of wastage11 because of prolonged convalescence and high recurrence rates. Although tendonitis can occur as a single-event injury, especially if the horse falls,12 stumbles, or trips badly, the condition most commonly results from repetitive cyclic loading. Unlike the suspensory ligament, tendons in adult horses do not strengthen in response to exercise and therefore are prone to develop accumulated microdamage during intense training. This damage can give the prodromal signs of slight filling or heat in the palmar metacarpal structures. The clinical signs of a SDFT strain then may develop acutely after a training canter or competition. For horses to develop subclinical tendonitis after a Three Day Event is not uncommon. The condition may not be apparent during the rest period after the competition but develops into clinical tendonitis when the horse resumes training or competitive work, even after 3 to 6 months. Close monitoring is thus essential, and I recommend routine ultrasonography after each Three Day Event. Ultrasonographic evaluation is important to assess the severity of injury and to determine a prognosis and an appropriate treatment plan. Lesion length and percentage of CSA involvement should be determined. Tendons may increase in CSA up to 10% normally with intense training, but this tends to return to baseline at the end of the season. If ultrasonographic examination is performed soon after injury, the extent of the lesion may not be apparent and severity may be underestimated. Severity of tendon damage is assessed most accurately 1 to 4 weeks after injury.

Initial treatment of event horses with SDF tendonitis is aimed at limiting inflammation and preventing any further tendon damage. The horse should be given box rest for 2 to 4 weeks, and antiinflammatory therapy should be commenced. Systemic NSAIDs appear to decrease swelling and pain, and no evidence indicates that they impede healing. Conversely, prolonged corticosteroid administration may interfere with fibroplasia, although a single systemic dose helps decrease inflammation without any apparent detrimental effects.

Support bandages or firm stable bandages should be applied for the first few weeks to reduce swelling. Topical dimethyl sulfoxide can be useful to decrease inflammation early after injury but should not be used for more than 5 days, because it can weaken collagen fibers and blister the skin. Local treatment with cold water hosing and ice application is beneficial while the signs of acute inflammation persist. For horses with mild-to-moderate injuries, the benefits of being able to perform local therapy seem to outweigh the greater external support that can be provided by application of a Robert Jones bandage.

In horses with severe SDF tendonitis in which loss of support (sinking) of the metacarpophalangeal joint has occurred, external support using a Robert Jones bandage is recommended. A heel wedge should be applied if the horse is severely lame. Heel elevation theoretically does not decrease load on the SDFT but appears to provide analgesia to horses that stand with the heel off the ground. In horses with severe breakdown injury, support with a proprietary splint, such as a Kimzey Leg Saver (Kimzey, Woodland, California, United States) is recommended.

Controlled exercise, to encourage development of a longitudinal fiber pattern but without placing excessive load on the tendon to damage the healing fibers, is the mainstay of recuperation. Serial ultrasonographic examinations are helpful to determine the appropriate rate of progress and the response to increasing exercise. After the period of box rest, walking in hand normally is commenced. Mechanical horse walkers appear detrimental in the early stages of healing, because constant turning places excessive load on a weak tendon. However, such walkers are extremely helpful after the initial 4 to 6 weeks of walking in hand, when duration of walking is increased. A major problem during this stage is degree of tolerance shown by the horse to this restricted level of exercise. Many horses are too excitable to be walked safely in hand, but they behave appropriately on a horse walker or if ridden under saddle. Exercise programs must be tailored to account for rider competence and the horse’s behavior. Once trotting has been commenced, the horse normally settles down into the exercise regimen.

A large number of treatment options exist for managing event horses with tendonitis. Tendon splitting, usually performed percutaneously in the standing horse, appears beneficial in horses with acute core lesions. Tendon splitting may decompress the core lesion and allow neovascularization but is most effective when performed in the first 10 days after injury. Intralesional injection of hyaluronan or a polysulfated glycosaminoglycan has not proved beneficial. Initial clinical studies investigating intralesionally administered β-aminopropionitrile fumarate unfortunately lacked representative control groups, and a licensed product is no longer available.

Intralesional injections of growth factors have been tried. Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and equine growth hormone, which induces the production of IGF-1, have been studied. I have had success in a small number of horses using transforming growth factor–β (TGF-β) in horses with tendonitis. The drug appears to promote fibroplasia. Although this gives a quicker healing rate and horses have returned to work successfully, whether the expected increase in strength and decrease in elasticity are desirable is theoretically debatable. I have had rewarding results using TGF-β in horses with chronic tendonitis. When ultrasonographic evidence of poor infilling exists, intralesional injection of TGF-β improves fiber pattern, and horses are able to withstand increased exercise intensity. After treatment, some horses have returned to CCI**** level and have completed successfully in up to three events. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) has been used more for ligamentous than tendonous injuries.

Desmotomy of the accessory ligament of the superficial digital flexor tendon (superior check desmotomy) also can be beneficial in selected horses, and performing the technique tenoscopically carries a much lower risk of postoperative incisional problems. Because of the risk of general anesthesia, I reserve its use for horses with recurrent tendonitis when there are very high owner expectations and for horses in which the ultrasonographic appearance of the SDFT deteriorates inappropriately during the controlled exercise regimen. In a small number of horses in trotting exercise after tendonitis, increased CSA and decreased echogenicity are observed. Even after the plane of exercise is reduced to walking for another 6 to 8 weeks or even longer, the ultrasonographic appearance of the SDFT does not change. After desmotomy, however, these horses tolerate an increased plane of exercise without ultrasonographic deterioration or subsequent recurrence of tendonitis. Because the procedure may increase the risk of suspensory desmitis after surgery, desmotomy should not be used in horses with a concurrent pathological condition of the suspensory apparatus. In a comparative discussion of outcomes for National Hunt horses with tendon injuries treated with different methodologies, superior check ligament desmotomy was the only one to show a significant improvement in outcome in comparison with conservative management, with shock wave therapy, IGF-1, and firing showing only trends toward improved outcomes.13

Stem cell therapy has become popular in some quarters (see Chapter 73), but I have not yet seen any clinically significant improvement in outcome and await the results of long-term studies. The expense and the delay in instigating treatment are off-putting. I currently use intralesional injections of bone marrow concentrate, made by processing bone marrow in a commercial system usually used for preparing PRP. This should yield some stem cells as well as growth factors and can be done on an outpatient basis.

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) can be beneficial. Subjectively I have felt that there is an improvement in the longitudinal fiber pattern. It is particularly useful in horses with mild or chronic tendonitis when there is no clear core lesion for injection.

Systemic medication with a polysulfated glycosaminoglycan is used as an adjunct treatment in horses with tendonitis. Ease of administration and lack of potential complications make such treatment popular, but no evidence indicates that any systemic medication, or feed supplement for that matter, has beneficial effects in tendon healing.

My current approach tends toward combined therapies, as none of the treatments individually have been shown to make any dramatic difference in outcome. Horses with core lesions would be treated with intralesional medication, followed by a course of ESWT and superior check ligament desmotomy if finances and the severity of the lesion justified it.

The total convalescent period depends on severity of initial injury, how well the injury appears to heal determined by ultrasonography, and the degree of compliance with the controlled exercise regimen. In horses with mild tendonitis (subtle loss of fiber pattern and <10% increase in CSA) as few as 6 weeks of walking exercise is sufficient. Horses with loss of fibers and frank tendonitis require a convalescent period of 9 to 15 months. Recurrence rate is less in horses that are given at least a year to recuperate before commencing full work. After tendonitis, many horses can be managed successfully to complete one Three Day Event, but sustaining the horse through a number of Three Day Events without recurrence is more difficult. A small number of horses seem to suffer recurrent clinical signs regardless of management protocol, and these are best restricted to One Day Events, in which they will often then compete successfully for many years.

Suspensory Desmitis

The two main levels of suspensory injury in the Three Day Event horse are branch desmitis and PSD. Midbody desmitis is rare. Suspensory branch desmitis can be considered an occupational disease of event horses. Advanced horses commonly develop inflammation and enlargement of the branches after a Three Day Event, and the condition is often transient with no associated lameness. Viewed by ultrasonography, the branches have periligamentous fibrosis with no areas of obvious hypoechogenicity, although some loss of longitudinal fiber pattern may occur. In many horses this pathological condition is missed or ignored, and the horse is just turned out. Even a short period of controlled exercise often decreases the risk of recurrence, however. Some degree of synovitis of the metacarpophalangeal joint commonly occurs and usually responds favorably to intraarticular medication.

PSD is a common cause of forelimb lameness.11 Lameness may be acute in onset, with inflammation obvious after exercise, or the disease can be insidious without any localizing signs. Diagnostic analgesia is mandatory, and ultrasonographic examination is valuable. Radiographic and scintigraphic examinations are useful adjunct tools. Most horses have true desmitis, although a small number have enthesopathy and associated bone remodeling, with clinically significant IRU and minimal ultrasonographic abnormalities. Most horses respond well to 4 to 9 months of controlled exercise, and no convincing evidence exists that any intralesional medications are beneficial. ESWT is commonly used to treat horses with suspensory desmitis. The analgesic effect may encourage a premature return to full exercise, thus increasing the risk of recurrence, and patience is still required in the rehabilitation of horses with acute injuries. ESWT is useful in horses with chronic, active desmitis, especially those with bone involvement that does not respond appropriately to controlled exercise.

I feel that PSD in hindlimbs is a most important but underdiagnosed condition. Similar to that seen in forelimbs, hindlimb PSD may cause acute or chronic lameness. The prognosis is generally much poorer for horses with hindlimb PSD, however, because of the development of a local compartment syndrome and associated pressure on the plantar metatarsal nerves. Thus most horses remain chronically lame, even after the ligament appears healed on ultrasonographic images. I have had success in treating event horses with persistent, chronic lameness with static or healed ligaments resulting from hindlimb PSD using local infiltration of triamcinolone acetonide (10 mg). Although lameness abates, treatment needs to be repeated at 6-month intervals and may be detrimental to the ligament in the long term. Thus a surgical technique has been developed for use in horses with chronic desmitis that has yielded extremely good results.14

The surgical technique involves the resection of a 4-cm segment of the common (deep) branch of the plantar metatarsal nerve, distal to its origin from the lateral plantar nerve. This is combined with incision of the fascia (fasciotomy) overlying the origin of the suspensory ligament. This technique combines decompression with analgesia and has allowed horses to return to a normal level of work within 3 months. The horses are restricted to walking only for the first month, after which time turnout and ascending exercise are permitted. I have operated on hundreds of horses, with a long-term success rate of around 75% and a low risk of more extensive suspensory ligament damage developing.

External Trauma

Event horses are prone to traumatic lacerations during competition, the most common being overreach injuries to the heel bulbs and skin abrasions and lacerations, particularly to the carpus and stifles.11 Standard principles of treatment apply, although owners often apply pressure to minimize healing time during the competition season. Aggressive early treatment is advised, and horses with deep foot or pastern wounds should be managed with a fiberglass cast for 10 to 14 days, a treatment that may shorten the convalescent period. Wounds should be assessed carefully for synovial penetrations. Thorn penetrations from brush or hedge fences can lead to infectious arthritis of the carpal or stifle joints, with only minimal clinical signs evident initially.

Direct trauma from jumping solid fences is common. Trauma directly over bone can lead to a severe, transient lameness. Acute lameness from this type of bone bruising can be difficult to differentiate from a fracture on an initial clinical examination. Trauma over the soft tissues may lead to the development of a considerable hematoma or edema, so local cold and pressure are indicated in the early stages.

Pain in the Sacroiliac Region

A low-grade form of sacroiliac disease is common in event horses and is manifest as a loss of impulsion and scope when jumping, with a reduced hindfoot flight arc. Most advanced event horses have bony pelvic asymmetry when critically assessed. Clinical signs include pain on palpation around the tubera sacrale and resentment of gentle lateral rocking action when the horse is in a weight-bearing position, with the opposite hindlimb held up. Often, associated muscle soreness and spasm are present in the surrounding musculature, notably the middle gluteal muscle. Most of these horses appear to have sacroiliac joint instability, but minimal evidence of IRU is seen on scintigraphic examination. Clinical signs can be localized by assessing the response to infiltration of local anesthetic solution around the dorsal aspect of the sacroiliac joint, using a spinal needle angled ventrocraniolaterally from just caudal to the opposite tuber sacrale. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the ventral sacroiliac ligaments per rectum also can be helpful to localize any pathological abnormality. The condition usually occurs when the horse is unfit and being brought into work or when the plane of exercise is increased. Sacroiliac pain often is self-limiting because the musculature increases as the plane of exercise increases and stabilizes the sacroiliac joint. Administering a systemic NSAID such as phenylbutazone helps the horse work through the period of lameness. Physiotherapy can assist in treating the local muscle spasm, and some horses improve with chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation. Horses with refractory pain sometimes improve after the local infiltration of methylprednisolone acetate (120 mg) or a sclerosing agent (e.g., P2G Solution [50 mL], Martindale Pharmaceuticals, Romford, United Kingdom), using the same approach as for local analgesia. Horses are continued in the same plane of work, and improvement normally is reported within a week. The duration of response varies, and some horses do not require repeat treatments.

Fractures in the Stifle Region

Fractures of the patella are common in event horses,15 and the imaging aspects have already been discussed. For medial fractures, surgical removal offers the best prognosis. The original surgical description is for an incision 15 to 25 cm in length, but I prefer to use arthroscopic guidance, enabling me to create a minimal surgical incision (5 to 7 cm) centered directly over the fragment. This is satisfactory for small fragments and also allows for thorough evaluation of the femoropatellar joint and easy removal of any loose fragments.

Other Fractures

Fractures caused by direct trauma of the distal phalanx and second and fourth metacarpal bones are not uncommon. Occasionally, condylar fractures of the third metacarpal or metatarsal bones or sagittal fractures of the proximal phalanx occur during training or competition, although they are rare. The standard considerations apply for evaluation and treatment. Vertebral or upper limb fractures can occur after a fall, and the initial evaluation can be complicated by adrenaline dominance.

Rhabdomyolysis

Recurrent rhabdomyolysis is relatively rare in advanced-level horses, because horses prone to this disease are selected out at the lower levels. Sporadic episodes are common at Three Day Events, however. Many potential trigger factors exist, including the stress of travel, stabling away from home, the competition itself, dehydration, climate changes, electrolyte imbalance, and dietary changes. I have noted a particularly high incidence in horses that were switched to haylage products immediately before a competition. This practice is done frequently because of the greater convenience of the small, packaged bales. A period of at least 4 to 6 weeks is recommended to allow adaptation to the new diet. The clinical manifestations at a Three Day Event can vary from collapse and recumbency on the roads and tracks phase in long-format competition to slight stiffness developing many hours after the completion of the cross-country phase of either short- or long-format competition.

To reduce the risk of rhabdomyolysis, attention should be paid to avoiding the trigger factors. Vitamin E levels are frequently low in event horse diets. Many commercial electrolyte preparations do not contain sufficient quantities of salt, and horses may be at risk if owners follow manufacturers’ recommendations. Routine blood sampling to monitor the muscle-derived enzymes aspartate transaminase and creatine kinase is performed frequently, but considerable fluctuation in asymptomatic event horses can occur,16 making interpretation difficult. This variation tends to decrease as horses become fitter, as the muscle cells appear less leaky. With the recognition of polysaccharide storage myopathy as a cause of rhabdomyolysis, some event horses have been successfully managed on a diet high in fat and low in soluble carbohydrates, although actual diagnosis is difficult to confirm.

Prevention of Lameness

When considering the time involved to train a horse to the top level and the potential for a long athletic career, preventing lameness is especially desirable in event horses. However, many important factors are beyond the veterinarian’s influence. The number and frequency of competitions, having the opportunity to choose events with good going and an appropriate riding surface, and a high standard of riding ability are factors difficult to control. The veterinarian may be able to assist with other factors such as a high standard of farriery and optimizing training programs. Regular veterinary monitoring can be valuable by allowing the early detection and treatment of any lameness problems. Monitoring for incipient SDF tendonitis by performing periodic clinical examinations, using thermographic and ultrasonographic examinations, and monitoring serum markers of tendonitis can be useful. Serial determination of markers such as cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) holds promise. Initial studies have shown that COMP increases as training intensity increases, and higher COMP levels are found in horses that subsequently developed SDF tendonitis.17 The concurrent use of all of these maximizes the veterinarian’s ability to detect subclinical tendonitis.

Many medications and supplements are sold with the aim of decreasing the risk of orthopedic disease. In racehorses, intramuscularly administered polysulfated glycosaminoglycan and intravenously administered hyaluronan have been shown to decrease the number of races missed, although the incidence of injuries was not decreased. Thus these drugs seem to be acting as antiinflammatory rather than as disease-modifying agents. Many commercial feed supplements are available but have unproven efficacy and variable and uncertain composition.