Chapter 114Prepurchase Examination of the Performance Horse

The purchase or prepurchase examination is a much discussed and sometimes feared subject for equine practitioners. Careless conduct and poor documentation can leave veterinarians wishing they had not agreed to perform the examination, whereas forethought and good planning can lead to a rewarding experience for the practitioner and the client. In the United States the examination is referred to as the purchase examination, because in many cases the deal already has been completed, whereas in Europe the examination usually is referred to as the prepurchase examination, because generally the purchaser has agreed to buy the horse subject to a satisfactory veterinary examination. In some countries (e.g., Holland), where many horses are sold through professional dealers, a horse may be purchased by the dealer and then examined by a veterinarian on behalf of the dealer before resale within a few days. In Europe young competition horses may be sold at auction and are subjected to a prepurchase examination before the sale. The terms of sale usually permit a purchaser to have an additional independent examination performed within a predetermined time after the sale.

Goals of the Examination

When requested to evaluate a horse for purchase, the veterinarian should keep several goals in mind. First, the examination should be an objective assessment of the horse’s physical condition. Second, the examination should be a fact-finding mission to aid the purchaser in his or her decision to make a purchase. This may involve the veterinarian in making some predictions based on experience and probability, but care must be taken to be factual and objective. Last, the examination can serve as a formal introduction to a horse for which the practitioner may provide long-term care. Such relationships may affect the veterinarian’s decision-making process relative to a client’s needs.

It is helpful to have knowledge of the disciplines for which the horse has been and is to be used. Various equine sports place differing demands on the horse, and the clinician should be aware of sometimes subtle, yet important, differences. Some physical characteristics or conditions may be acceptable for certain levels of performance but not acceptable for others. For example, a previous strain of a superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) may be an acceptable risk for a show hunter but may carry a high risk for an event horse. Veterinarians should avoid performing prepurchase examinations on horses that will be involved in disciplines with which they are not familiar.

The veterinarian needs to discuss the goals of the examination and horse ownership with the prospective purchaser. Understanding the client, the trainer, and what is expected of the horse will help the veterinarian in assessing the horse’s potential suitability. Passing or failing the horse is not the veterinarian’s job, but it is his or her role to advise on how existing conditions may affect the future use of the horse. It is therefore self-evident that prepurchase examinations should not be performed by recent graduates, who may be fully competent in performing clinical examinations but generally do not have the experience of how to interpret the findings of the examinations and are not in a position to evaluate risk. The prospective purchaser requires advice about the risks of proceeding with the purchase. Prior knowledge of clients, their expectations of the horse, and their attitude toward risk make offering such advice easier, compared with clients about whom clinicians know little.

A veterinarian must be open-minded and should consider himself or herself to be a facilitator for the sales contract: the vendor wishes to sell the horse, the purchaser may have searched for a long time to find a suitable horse, and the veterinarian’s role is to enable the transaction to take place if such is reasonable. Nonetheless, the veterinarian must be streetwise and recognize that a minority of unscrupulous vendors may try to misrepresent a horse. Caveat emptor. Veterinarians also should be aware that prospective purchasers often are keen to buy horses and in their enthusiasm may wish to overlook any problems that are identified during the examination. A veterinarian who believes that the risks of buying a horse are too high is responsible for trying to dissuade the purchaser from proceeding further. If the purchaser ignores the advice, it is essential that the veterinarian documents adequately his or her observations and advice. Purchasers can have remarkably selective memories when things start to go wrong.

The scope of the examination can range from a comprehensive clinical examination of the horse, using basic powers of observation, to a complex investigation using advanced techniques such as radiography, ultrasonography, endoscopy, thermography, scintigraphy, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The wishes of the buyer are important in determining the extent and depth of the examination, which also must be dictated to some extent by the value of the horse and its future athletic expectations. Some consideration to cost should be given, but not at the cost of the quality of the examination. The veterinarian should allow some latitude for deciding what is needed to answer questions posed by the clinical examination.

Contract

A veterinarian enters a business arrangement with a purchaser when he or she agrees to perform a prepurchase examination. It is imperative for the veterinarian to understand the buyer’s intentions for the horse and the expectations of the proposed examination. The terms, details, and costs of the examination should be discussed at the time of the initial request. The extent and depth of the examination and its limitations should be emphasized. This is straightforward when the veterinarian is dealing directly with the purchaser, assuming that the purchaser has knowledge of horses. The terms of agreement become more difficult when a veterinarian is speaking to an agent for the potential owner or to the prospective rider of the horse, when the actual purchaser has no knowledge of horses. Such persons may have expectations of the horse as if it were a mechanical object like a car.

Purchaser’s Reservations

The veterinarian is responsible for the following:

Purchase for Resale

If the horse is to be purchased for resale, this should be noted. The purchaser should be warned that the clinician’s interpretation of the findings may not be identical to that of another veterinary surgeon. The examining veterinarian may regard the horse as a reasonable risk for purchase, but this is not a guarantee that others have the same opinion. All observations should be well documented so that comparisons can be made should questions arise at a subsequent resale examination. Such notes may well help save a sale in the future and save face for the initial veterinarian.

Insuring the Horse

It is important to establish if the horse will be insured for loss of use for a specific athletic activity or for veterinary fees. The purchaser should be advised that the examining veterinarian may consider the horse a reasonable risk for purchase but that does not necessarily equate with the horse being a normal insurance risk. The veterinarian may consider that a small, well-rounded osseous opacity on the dorsal aspect of the distal interphalangeal joint is unlikely to be of clinical significance, but for an insurance company to place an exclusion on problems related to the joint would not be unreasonable. The veterinarian should advise the purchaser that if such problems arise, the purchaser should communicate with the insurance company before completing the purchase transaction.

Blood Tests and Limitations

The client should be informed clearly that the results presented are good for the day of examination, but predictions about future soundness and suitability are impossible. The limitations of analysis of blood for drugs must be detailed, bearing in mind the difficulties of detection of many drugs administered by the intraarticular route. The client should be warned that several days may elapse before the results of blood tests are known and that the purchase transaction should not be completed until the results are known. The veterinarian should discuss with the client how the findings will be transmitted and what kind of report will be issued.

Conflicts of Interest

Any potential conflicts of interest for the veterinarian must be disclosed to the buyer. Previous dealings with the vendor, although the vendor may not be a current client, could be perceived as a conflict of interest. In the horse world today, not to have such conflicts arise is difficult, but such conflicts should be acknowledged, and the buyer should be given the option of having someone else perform the examination.

Communication with the Vendor

The vendor must understand clearly what facilities are required for the examination and should be advised that the horse should be stabled before the examination and not worked earlier in the day. If the vendor is unable to be present at the examination, the veterinarian should establish the answers to a number of important questions in advance:

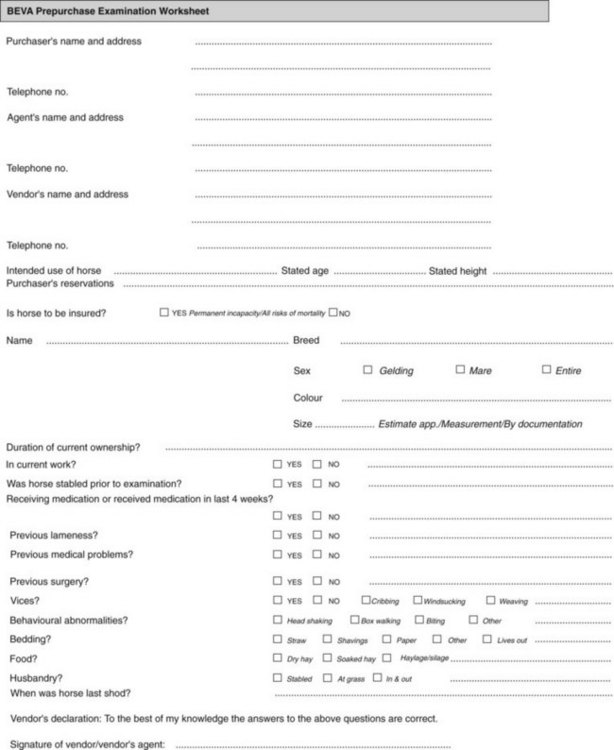

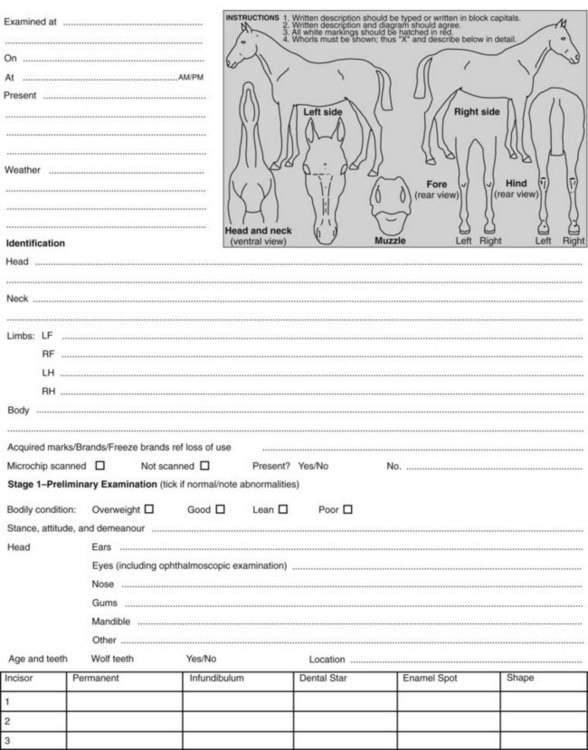

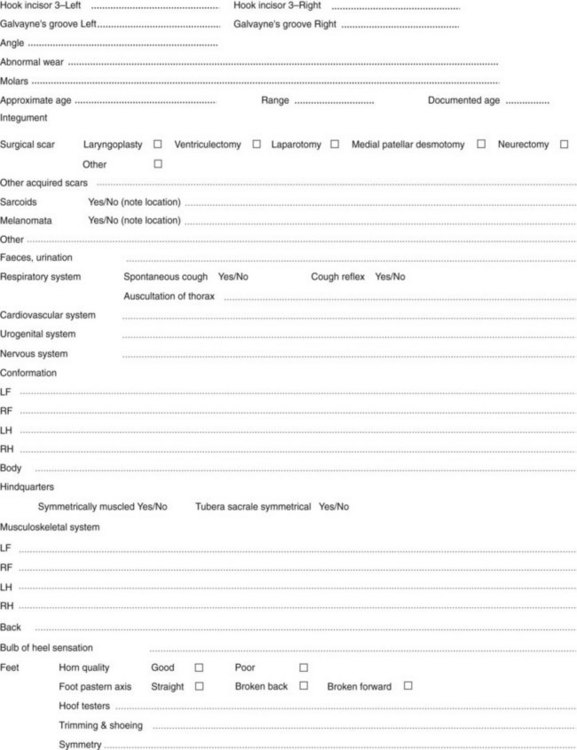

Ideally vendors should sign a copy of their responses to these questions (Figure 114-1).

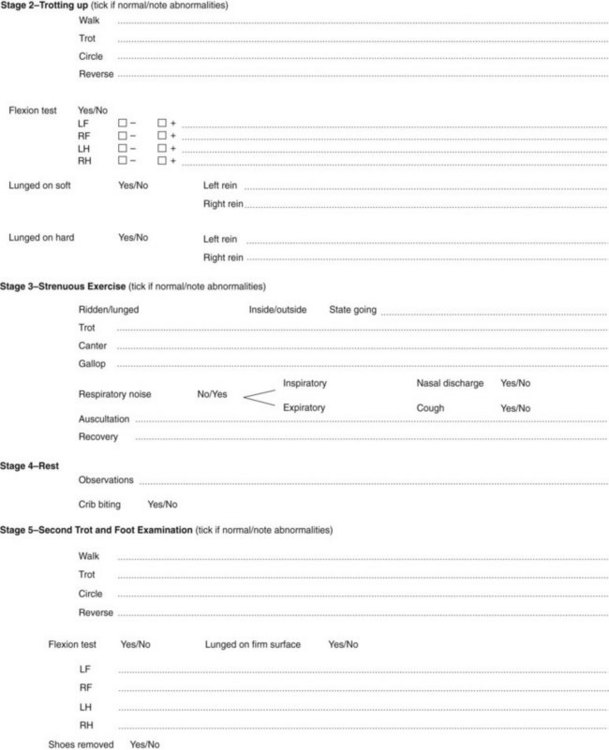

Fig. 114-1 British Equine Veterinary Association prepurchase examination worksheet. D, Dorsal; Di, distal; L, lateral; LF, left forelimb; LH, left hindlimb; M, medial; O, oblique; P, proximal; Pa, palmar; Pl, plantar; RF, right forelimb; RH, right hindlimb; URT, upper respiratory tract.

(Courtesy British Equine Veterinary Association.)

When the examination actually is performed, ideally all involved parties or their agents should be present. This provides an environment in which the veterinarian can ask pertinent questions of the buyer and seller regarding the horse’s history and future use and can assure the buyer that a complete examination has been performed. Problems that arise during the examination can be discussed with the purchaser.

The veterinarian should not compromise the standard of the examination because of physical conditions. If modifying the procedure of the usual examination technique is necessary, such should be noted in the subsequent report, and the purchaser should be advised accordingly. The limitations of the conclusions drawn from the examination should be documented. If an uncooperative vendor or agent makes conducting the usual examination difficult, the veterinarian may choose not to continue the examination to protect the interests of the buyer and personal interests.

Examination at a Distance

A client may request the veterinarian to examine a valuable competition horse that is a long distance away or possibly in a foreign country. A number of alternative strategies can be applied. It may be prudent to first have the horse undergo radiographic examination and proceed with visiting the horse only if these radiographs are considered acceptable. The veterinarian is of course relying on the honesty of everyone concerned that the radiographic images provided are current images of the horse in question. It is critical that the veterinarian provide clear guidelines of the views required and be prepared not to compromise on quality. Alternatively, the veterinarian can travel and examine the horse and be present for the radiographic assessment. However, this may mean that the clinical examination is compromised by inadequate riding facilities at a veterinary clinic or that substantial time is spent traveling between the site where the horse is examined and the veterinary clinic where ancillary tests are performed. However, clinic facilities may be required anyway for additional examinations such as ultrasonography or endoscopy.

A client may inform the veterinarian of an intended purchase of a horse from a foreign country and that it has been recommended that he or she employ a specific clinician from that country to carry out the prepurchase examination. The client should be warned that the method of carrying out and reporting the examination may differ from what he or she is used to seeing and may have limitations of which he or she is unaware. For example, in some countries in Europe the examination is much more limited and does not encompass assessment of conformation. It is not usual practice to examine the horse being ridden. It is worthwhile developing a group of professional colleagues whose clinical expertise and trustworthiness the veterinarian respects, one of whom can be recommended to the purchaser. The veterinary surgeon performing the examination should be requested to communicate with the client’s own veterinarian and to send radiographs for assessment. Discussion between two colleagues—one who has examined the horse and the other who knows the client—can result in a highly satisfactory outcome.

Clinical Examination at Rest

Various national bodies have established guidelines for the way in which a prepurchase examination should be carried out and reported, to which the veterinarian obviously should adhere. The legal responsibilities for the veterinary surgeon and the vendor may vary in different countries. For example, in Holland the expectations of the veterinary examination performed on behalf of an amateur purchaser are higher than for a professional purchaser. In Denmark, if clinically significant radiological abnormalities that obviously predate the purchase are discovered soon after purchase, the vendor is liable.

The clinical examination should evaluate all organ systems as comprehensively as possible. The examination should be methodical and repeatable. Using a checklist may help. The principal aims of this chapter are to focus on the examination of the musculoskeletal and neurological systems1,2 and to discuss the interpretation of abnormal findings.

The veterinarian should identify the horse, including name, breed, sex, age, markings, tattoos, freeze marks, brands, and height. In Europe a freeze brand L signifies that the horse has previously been a loss of use insurance case. The horse’s identity should be compared with its passport or vaccination certificate.

The horse first should be examined in the stable, with assessment of demeanor, attitude, stance, and conformation and thorough observation and palpation of the head, neck, back, and limbs as described in Chapters 4 to 6. Collection of blood samples may be performed at this stage or when the examination is completed and the veterinarian deems that purchase will probably be recommended. More comprehensive evaluation of the feet, overall conformation, and evaluation of muscle symmetry is best performed outside, where the horse can be viewed better from all angles.

If the horse will be used for show purposes, in which the cosmetic appearance of the horse is important, the veterinarian should draw the purchaser’s attention to all possible abnormalities, such as a prominent base (head) of the fourth metatarsal bone that a lay judge may misconstrue as a curb. If the purchaser has expressed reservations about a swelling such as a splint, the veterinarian should be sure to document its size and possible importance. If the purchaser is concerned about the horse’s hock conformation, recommending radiographic examination of the hocks is worthwhile, even if the veterinarian considers the conformation to be acceptable and the horse appears sound.

Conformation

Although assessment of conformation as far as it may influence future lameness is considered an important part of the examination in the United States and United Kingdom, this is not usual practice, and in Holland, for example, is not included. It is important to recognize that breed differences in conformation exist and that what might be acceptable in one breed does not necessarily apply to others. The relevance of conformational abnormalities in part is dictated by the discipline in which the horse is involved.1

Most Arabian horses have a short-coupled and slightly lordotic back; thus they are likely to have some degree of impingement of dorsal spinous processes. This is unlikely to compromise the horse’s show performance. However, a dressage horse with a short back may well develop a clinical problem associated with impinging dorsal spinous processes when working at an advanced level. In such a horse the flexibility of the back at rest and when the horse is moving in hand and ridden must be assessed with great care, paying great attention to the freedom and elasticity of the gaits. Even if the horse is currently free of clinical signs, the purchaser should be advised that problems may occur in the future.

Young Warmblood breeds have a relatively high propensity for intermittent upward fixation or delayed release of the patella, especially those with a straight hindlimb conformation. Although the condition may be manageable in some, in others it can become a chronic problem, albeit a subtle one, resulting in low-grade discomfort and unwillingness to work. The veterinarian should observe the horse carefully as it moves over in the stable, to assess smooth or jerky movement of the patella on the left and right sides, and should check carefully for a surgical scar and the size of the medial patellar ligament, which if enlarged is likely to reflect a previous desmotomy or desmoplasty.

Very straight conformation of the hocks and abnormal extension of the hind fetlock joints are predisposing factors for and may be indicative of proximal suspensory desmitis and suspensory branch injury. The client should be advised of the potential importance of such findings and asked whether he or she wishes the examination to be continued. It may be preferable that the examination be terminated at this stage rather than the veterinarian running up a large bill and antagonizing the vendor by wasting more time.

The clinician should pay particular attention to the conformation of the feet and relate this to the type of ground surface on which the horse will have to work. A horse with flat feet and thin soles is not a good candidate for endurance riding. A horse with crumbly hoof walls is predisposed to losing shoes, and this can be disastrous for Three Day Event horses. Although changing the horse’s nutrition and foot management may result in some improvement, accurate prediction of the degree of improvement that may be achieved is difficult. Sheared heels and underrun heels in the forelimbs or hindlimbs may be primary problems or predispose horses to altered ways of moving, causing soreness in the more proximal parts of the limbs. These findings are particularly important in jumping and dressage horses and those used for cutting and reining.

The veterinarian should assess the forelimb conformation carefully from the front and ensure that the foot is positioned symmetrically under the central limb axis of the more proximal parts of the limb. A disproportionately high incidence of distal limb joint problems occurs in horses in which the pastern and foot are set more to the outside, with a tendency for the medial wall to become more upright and the lateral wall to be flared (Figure 114-2).

Fig. 114-2 Dorsal view of a forelimb with clinically significant conformational abnormalities. Medial is to the left. Note the position of the foot and pastern relative to the central axis of the metacarpal region (dotted line). The hoof capsule is distorted, and the foot shape is asymmetrical.

Many Warmblood breeds naturally have much narrower and upright foot conformation than other breeds. This predisposes the horses to develop thrush, and careful stable hygiene and foot cleanliness are necessary to control this problem. Asymmetry of front foot shape and size always should be documented and may reflect previous lameness in the limb with the more contracted foot, but it also may reflect development of a mild flexural deformity of the distal interphalangeal joint when the horse was a foal, which may be of no long-term relevance. The veterinarian should beware if the feet are long and misshapen; this finding may mask underlying conformational problems or asymmetry in foot shape and size. Postponing further assessment of the horse until the feet have been trimmed and shod properly may be preferable.

Some conformational abnormalities, such as over at the knee, do not appear to influence a horse’s future soundness greatly but must be described. Failure to document observations leaves the veterinarian open to litigation if future problems arise.

Muscle Symmetry

Muscle asymmetry of the hindquarters may reflect previous or current hindlimb lameness, although it is not necessarily associated with future chronic lameness. Muscle asymmetry should alert the veterinarian to pay particular attention to the hindlimb gait in hand, on the lunge, and ridden and to the response to flexion tests. Asymmetry is an indication for flexion tests before and after ridden exercise. The potential clinical significance of muscle asymmetry must be discussed with the purchaser. Slight asymmetry of the tubera sacrale is a common finding and frequently is not of clinical significance. Nonetheless, the purchaser should be informed of its potential clinical significance.

Tendons and Ligaments

Particular attention should be paid to the size, shape, and stiffness of the tendonous and ligamentous structures of the metacarpal and pastern regions, bearing in mind that if the horse has sustained a bilateral tendon injury, both tendons may be enlarged slightly, and the clue to previous damage may be rounding of the margins of the tendons or abnormal stiffness. The clinical significance of a previous injury to the SDFT or suspensory ligament must be assessed in light of the horse’s previous and future career. These injuries carry a high risk of recurrence in racehorses, event horses, high-level show jumpers, and endurance horses. However, the horse may perform satisfactorily as a hunter, a dressage horse, or a pleasure horse or at a low level in more demanding sports. The purchaser should be advised that further information about the repair of the injury may be obtained by ultrasonographic examination. Further information about when the injury was sustained and what the horse has done since then may be helpful. Decision making must be based on the athletic expectations of the horse, all other aspects of the horse’s suitability, and whether the horse is being bought for resale. If the horse is a perfect schoolmaster for a junior rider and the price is reasonable, the risk/benefit ratio may be acceptable.

Assessment of Joints

Many horses have mild fetlock joint capsule distention or thickening. The relevance of distention must be assessed based on the environmental temperature: if it is cold, joint capsules are more likely to be tight than if it is warm. Asymmetry between left and right is of greater clinical significance than bilateral symmetry. The joints should be assessed carefully for any evidence of restricted range of motion or pain on manipulation. The range of motion varies among horses and is in part a reflection of age and work history, but asymmetry between left and right should be viewed with caution. The response to distal limb flexion and the horse’s action on the lunge on a hard surface must be assessed carefully. Distention of the antebrachiocarpal or middle carpal joint capsules is rarely an insignificant finding and even if unassociated with detectable lameness should prompt radiographic examination.

During hindlimb assessment, care should be taken to differentiate between pain on flexion of the proximal limb joints and reluctance to stand on the contralateral hindlimb, perhaps associated with sacroiliac pain. Abnormal limb flexion may be present if the horse is a shiverer. A high incidence of this condition occurs among high-performance Warmblood breeds, and it does not appear to compromise performance. However, an intending purchaser must be warned that the condition may be progressive and may make the horse difficult to trim and shoe.

Flexibility of the neck and back should be assessed, and the presence of any abnormal muscle tension or abnormal reaction to palpation of acupuncture trigger points should be noted. The veterinarian also should pay attention to the presence of sarcoids in a position where they may be abraded by tack. If a sarcoid is identified, the client always must be warned that such lesions may increase in number, but assuming that the client is aware of the risks, a small number of lesions at sites removed from the tack should not mitigate against purchase. The mouth should be examined carefully. Large hooks on the rostral aspect of the first upper cheek teeth are usually an indicator that large hooks also may be present on the caudal aspect of the lower caudal cheek teeth, which may be difficult to manage.

Sensation in the heel region of the forelimbs and the reaction to vigorous application of hoof testers should be assessed carefully to determine if a previous neurectomy may have been performed. The absence of a visible or palpable scar does not preclude previous surgery.

Assessment of Gait

The horse should be examined moving freely at a walk and trot on a firm surface, with particular attention directed to the stride length and lift to the stride relative to the horse’s type. The veterinarian should bear in mind that a horse with a bilateral forelimb or hindlimb lameness may not appear overtly lame, but merely may have a slightly restricted gait. The veterinarian should beware of the situation encountered particularly in a professional’s yard when the horse is encouraged by an assistant to trot excessively quickly, is unduly restrained, or is excessively fresh and trots crookedly. The horse must trot in a regular, relaxed rhythm with freedom of the head and neck; otherwise, lameness may be missed. The veterinarian should pay particular attention to how easily the horse turns when changing direction and the flexibility of the neck and back. If the horse trots in a particularly loose and extravagant way, the veterinarian should bear in mind that the horse may be mildly ataxic. Ataxia may not jeopardize a dressage horse when competing at lower levels, but when finer degrees of muscular strength and coordination are required in advanced dressage, performance may be compromised. The safety of a mildly ataxic horse jumping must be questioned. The veterinarian should watch the horse carefully as it decelerates, when signs of mild ataxia or jerky movement of the patella associated with its delayed release may be apparent. Watch the horse turning in small circles and moving backward, assessing flexibility of the neck and back, limb coordination and placement, and any quivering movement of the tail suggestive of shivering.

Flexion Tests

The interpretation of flexion and extension tests is controversial.3,4 The force applied, the duration of flexion, the way in which the joints are flexed, and the work history of the horse may all influence the response. Positive results of flexion tests in a horse that does not demonstrate lameness before flexion may not be a cause for termination of the examination, unless other suspicious clinical signs have been identified already. The horse should be evaluated on the lunge and ridden for evidence of lameness. Many positive results on flexion tests are found to change during the course of the exercise examination (perhaps as the horse warms up or loosens up), and these may not have clinical significance. A difference in response between distal limb flexion of the left and right forelimbs may be more important than a symmetrical response. A positive response to carpal flexion or to proximal limb flexion of a hindlimb must be viewed with caution. Veterinarians should aim to perform flexion tests as consistently as possible so that they know the ranges of response anticipated in clinically normal horses.

Lunging and Ridden Exercise

The requirements for lunging and ridden or driven exercise vary among the guidelines for prepurchase examinations in different countries and also are dictated by the type of horse under examination. The methods used for a 3-year-old Thoroughbred racehorse differ from those for a 6-year-old destined for eventing. Seeing the horse lunged on soft and hard surfaces and ridden is helpful to gain maximum information about any potential lameness problems. The vendor should be encouraged to use any protective boots or bandages that might be used normally. Subtle lameness or restriction in gait because of thoracolumbar or sacroiliac discomfort may not be evident until the horse performs specific movements when it is ridden.5,6 Small figure eights and upward and downward transitions may be particularly revealing. Watching the horse do what it specifically is intended to do is good practice. The veterinarian should watch the horse being tacked up and mounted to learn about any cold back behavior or evidence of back pain or other behavioral abnormalities. The horse should be worked reasonably hard relative to its fitness. In many European countries, evaluating a ridden horse is not standard practice, and if an examination is being performed on behalf of the client by a foreign veterinarian, the client should be advised accordingly.

Clinicians who have the prerequisite skill and experience may wish to evaluate horses further by riding or driving them themselves. Feeling the horse in this fashion may answer questions regarding a peculiar gait or way of going and may aid the evaluation of subtle lameness or respiratory noises. Such practice should be done with caution, because legal problems could arise from an unfortunate accident. A signed disclaimer may be helpful in this situation.

After strenuous exercise the horse should be allowed to stand for 15 to 20 minutes before being reevaluated in hand at the walk and the trot. This is a mandatory part of the examination in the United Kingdom but is not practiced widely in the rest of Europe. Previously inapparent lameness now may become evident. Any previously questionable response to flexion tests may be reassessed.

Evaluation of Identified Problems

The veterinarian should now have gained enough information either to discontinue the examination after consultation with the purchaser or to make recommendations for further special examinations. If the horse is lame and a potential cause that may resolve is obvious (e.g., nail bind), reevaluating the horse on a subsequent occasion may be worthwhile, but the veterinarian should try to ensure that the horse has been worked properly for several days before the reexamination.

The veterinarian should always bear in mind that in a mature competition horse, it is relatively unusual not to identify some problems. Taking no risks and advising against purchasing the horse is easy, but that actually may be doing the purchaser, the vendor, and the veterinary profession a disservice. It is important to weigh the risks and describe them to the purchaser as objectively as possible, based on previous experience. At this point having in-depth knowledge of the purchaser, his or her aspirations for the horse, and the attitude to risk and financial ability to take the consequences of risk is most valuable. Further information obtained from radiographic and ultrasonographic examinations may help provide further objective information on which decisions can be based. Decisions also must be related to the horse’s recent competition record, its age, and the future expectations for athletic performance. Low-grade hindlimb lameness associated with mild radiological changes of the distal hock joints might be an acceptable risk for a horse as a schoolmaster for a young rider, but similar abnormalities identified in a 6-year-old about to step up a level in competition must be regarded as potentially more serious. A veterinarian always must bear in mind that minor problems may become major problems with a change of rider, work pattern, and environment.

Rectal Examination

Rectal examination is not a routine part of a prepurchase examination and should be performed only with the vendor’s consent if indicated clinically or if a mare is to be used later for breeding or has a recent history of breeding.

Radiographic Examination

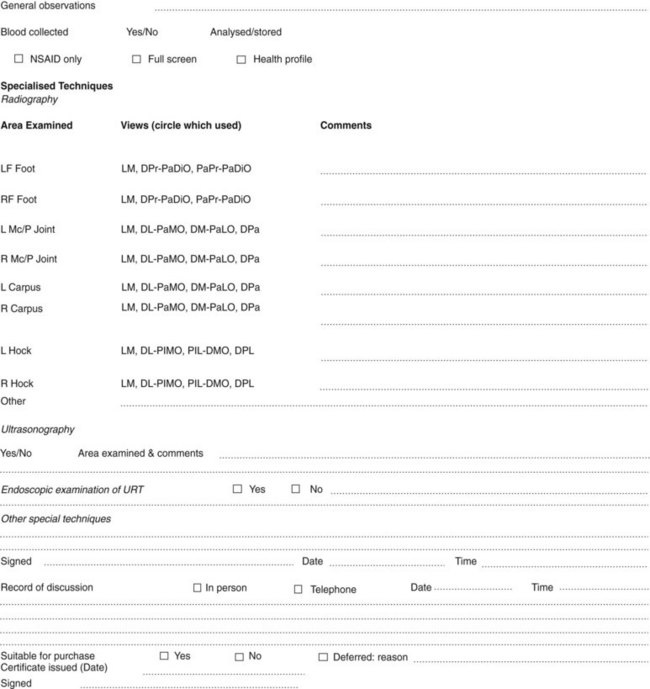

Radiographic examination is not a standard part of a prepurchase examination. The extent of routine radiographic examination in the United States and some European countries is probably higher than elsewhere. In Holland and Germany a strict grading system for evaluation of radiographs is used. The purchaser must be made aware that the presence of some radiological abnormalities is not necessarily synonymous with future lameness and the absence of radiological changes does not preclude future lameness.7 If radiographs are to be obtained for a specific area, then a comprehensive set of radiographs should be ordered to avoid missing lesions apparent on only one images. In many European countries, obtaining only three images in evaluation of the hocks and omitting a dorsomedial-plantarolateral oblique image are common. This practice may risk the veterinarian missing lesions such as periarticular osteophytes, which are present only on the dorsolateral aspect of the joints (Figure 114-3).

Fig. 114-3 Dorsomedial-plantarolateral oblique radiographic images of the left (A) and right (B) hocks of a 9-year-old Grand Prix show jumper. There is a small osteophyte on the proximal aspect of the third metatarsal bone (MtIII) (arrow), and subtle modeling of the articular margins of the centrodistal joint is present in each hock. The horse was clinically sound. C and D, The same horse 24 months later. At this stage the horse showed right hindlimb lameness that was alleviated by intraarticular analgesia of the tarsometatarsal joint. Considerable periarticular osteophyte formation (arrows in D) involves the centrodistal and tarsometatarsal joints of the right hock (D). The spur on the dorsoproximal aspect of the left MtIII was little changed (arrow).

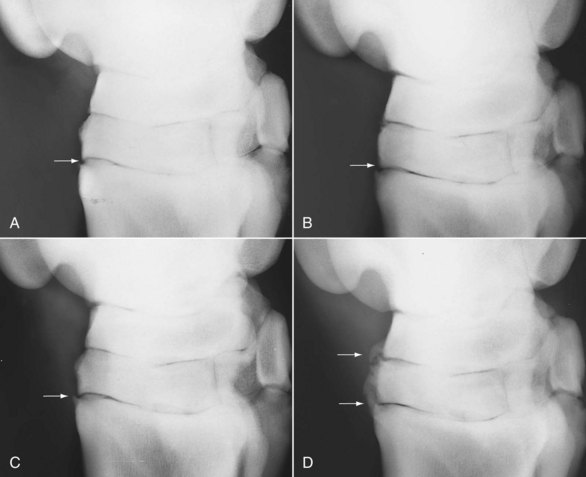

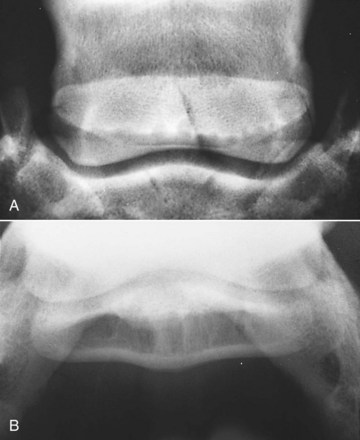

The regions to be examined and the interpretation of findings are dictated by the previous and intended career of the horse and the results of the clinical examination. Examination of the front feet, fetlock, and hock joints is considered routine in many countries. Evaluation of the carpi, hind fetlock and pastern joints, stifles, and dorsal spinous processes of the thoracic region may be considered. It is, however, important not to overinterpret the clinical significance of some radiological abnormalities, bearing in mind the variability among breeds and the knowledge that even some obvious changes may be clinically insignificant. For example, Warmblood breeds have a tendency to have a greater number of radiolucent zones along the distal border of the navicular bone than do Thoroughbreds (Figure 114-4). A relatively high incidence of spur formation on the dorsoproximal aspect of the middle phalanx occurs in Warmbloods (Figure 114-5), but this rarely is associated with lameness. However, one of the authors (RDM) recognizes a higher incidence of clinically significant osteoarthritis (OA) of the proximal interphalangeal joint in Warmblood horses compared with other breeds.

Fig. 114-4 A, Dorsoproximal-palmarodistal oblique image of the right front foot of a clinically normal 6-year-old Dutch Warmblood horse with good foot conformation. Note the large size and number of the radiolucent zones along the distal border of the navicular bone. The horse competed successfully for many years with no evidence of foot pain. B, Palmaroproximal-palmarodistal oblique image of the same foot. Note the large, oval-shaped lucent zones in the medulla of the navicular bone.

Fig. 114-5 Lateromedial radiographic image of the left front pastern of a clinically normal 7-year-old Belgian Warmblood show jumper. Note the modeling of the dorsoproximal aspect of the middle phalanx (arrow). Such spurs are a common finding in Warmblood breeds and usually are not associated with lameness.

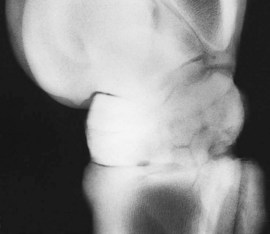

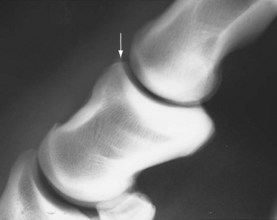

Evidence of abnormal radiolucent zones in the proximal sesamoid bones (sesamoiditis) (Figure 114-6) should alert the veterinarian to reevaluate the branches of the suspensory ligament. An ex-racehorse may have periosteal new bone on the dorsal aspect of one or more carpal bones, but this is unlikely to influence the horse’s career as an event horse. A horse with a small osteochondral fragment on the dorsal aspect of the distal interphalangeal or metacarpophalangeal joint is often asymptomatic.

Fig. 114-6 Dorsolateral-palmaromedial oblique image of a 6-year-old Thoroughbred that had raced previously on the flat and was used now for eventing. Note the large lucent zones in the lateral proximal sesamoid bone. The horse had no history of lameness.

A small spur on the dorsoproximal aspect of the third metatarsal bone (MtIII) is a frequent incidental finding.8 However, such findings also must be described to the purchaser, and the potential future clinical significance must be discussed. Small spurs on the dorsoproximal aspect of the MtIII do not necessarily reflect OA but may reflect entheseous new bone at the attachment of the fibularis (peroneus) tertius or cranialis tibialis. Despite the fact that these spurs are a common finding, accurately predicting the future behavior is impossible. Some spurs may reflect OA and may be progressive (see Figure 114-3). A 3-year-old that has done little work and has small osteochondral fragments at the cranial aspect of the intermediate ridge of the tibia may be asymptomatic, but if fragments became unstable with increased work, it might result in distention of the tarsocrural joint capsule, and surgical removal may be indicated. Such a finding in a mature competition horse is usually of no consequence. Complete fusion of the centrodistal (distal intertarsal) joint may be identified unassociated with any other radiological change of the hock (Figure 114-7). Some horses may compete successfully with such changes for many years, but occasionally lameness subsequently develops because of pain associated with the talocalcaneal-centroquartal (proximal intertarsal) or tarsometatarsal joints. Well-rounded osseous opacities frequently are identified distal to a proximal sesamoid bone (Figure 114-8). These are often innocuous, but ultrasonographic evaluation of the distal sesamoidean ligaments may be indicated. Evidence of osteochondrosis of the trochleas of the femur is of concern in a 3-year-old, even if the horse is asymptomatic, whereas mild flattening of the lateral trochlear ridge of the femur in a 10-year-old jumper free from lameness would be of no concern.

Nuclear Scintigraphic Examination

Nuclear scintigraphic examination is not a routine part of a prepurchase examination. If the horse is clinically normal, the interpretation of results of whole body screening is difficult. This practice should be discouraged. In selected horses when interpretation of the clinical significance of specific radiological abnormalities may be in dispute, focused nuclear scintigraphic examination may be helpful.

Ultrasonographic Examination

Ultrasonographic examination of the limbs requires three important prerequisites: high-class image quality, experience of interpretation (knowledge of normal anatomy and its variations and the ability to detect abnormality and to interpret its potential clinical significance), and client compliance. A number of clinical situations occur in a prepurchase examination in which ultrasonographic examination provides invaluable clinical information not otherwise available. These situations include the following:

Interpretation of findings in a horse with no identifiable clinical abnormality may not be straightforward, but enlargement of a tendon or ligament usually does reflect previous injury, the future relevance of which depends on the intended use of the horse, chronicity of the lesion, severity of the lesion, and degree of healing.

If ultrasonographic examination is recommended but is refused by the vendor or the purchaser, this should be noted on the prepurchase examination certificate.

Thermographic Examination

Thermography also may provide a useful indicator of low-grade inflammation and help to identify signs of early tendonitis, suspensory desmitis, and splint development. However, a normal thermographic appearance does not preclude the presence of a subclinical tendon lesion.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The availability of MRI (especially the standing application) may lead to requests for more “thorough” examinations. MRI should be discouraged as a routine procedure because of the high probability of finding lesions in otherwise sound mature performance horses. It may be appropriate in situations where unusual radiological or ultrasonographic lesions are found, to further assess the possible clinical significance.

Blood Tests

The use of blood tests is controversial, and limitations should be discussed with the prospective purchaser. Screening for nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, mood-altering drugs, sedatives, and possibly also corticosteroids is advisable, but the purchaser must be aware that blood tests are less sensitive for these drugs and metabolites than is urine analysis. If the vendor knows in advance that the horse will be tested, this knowledge may provide a deterrent to the unscrupulous. Alternatively, blood may be collected and stored suitably and be analyzed only if a problem arises within the first few weeks of purchase. In the United Kingdom the Veterinary Defence Society and the Horse Race Forensic Laboratory run a scheme jointly. The vendor signs a form to permit collection of the sample in a specialized container provided by the Horse Race Forensic Laboratory, to which is applied a bar-coded label. The purchaser can elect to have the sample analyzed immediately for a fee or it can be stored at the Horse Race Forensic Laboratory at no charge with the potential for analysis at a later date. This system has proved to be legally robust.

The purchaser must be aware that drugs administered intraarticularly may not be detectable, depending on the nature of the drug and the time of administration relative to the time of examination. In professional dealers’ yards in Europe, a high incidence of joint medication to mask lameness occurs.

If the horse is being purchased in one country for export to another, testing for evidence of specific diseases may be necessary. For example, horses entering the United States should be tested for equine infectious anemia, dourine, glanders, and piroplasmosis. A horse from an area where African horse sickness has occurred should be tested. Testing stallions going to the United States for equine viral arteritis is advised. Positive horses may not be permitted back into the European Union and other regions without extensive testing and potential limitations.

Screening for contagious equine metritis may be indicated. Use of hematological and serum biochemical screening and other assays, such as measurement of cortisol and insulin, as an aid to detect equine Cushing’s syndrome in older horses is controversial. Routine hematology and serum biochemistry may be useful to ensure that the horse is healthy at the time of the examination. Serum testing for equine protozoal myelitis potentially is misleading and should be actively discouraged.

Nerve Blocks

In some circumstances, nerve blocks may aid interpretation of clinical findings. A horse may appear completely sound under all circumstances but have an unusually short forelimb stride. Does this reflect bilateral foot pain, or is this gait completely normal and natural for this horse? With the vendor’s permission this question could be answered by bilateral perineural analgesia of the palmar nerves at the level of the proximal sesamoid bones. However, nerve blocks are not without complications and only establish the region of the pain causing lameness at best. Pursuing this course may prove frustrating and not elucidate the cause of the lameness

If a horse is lame but the vendor claims that the horse has never been lame previously, the situation should be discussed with the purchaser. Reexamining the horse on a subsequent occasion may be best, but the vendor should be advised that after resolution of the lameness the horse must be worked for at least a week before reassessment. The veterinarian should ask the vendor to sign a form declaring that the horse has been worked properly and has not received medication, and the veterinarian should collect blood for medication testing when the horse is reexamined.

The examining veterinarian’s role is not to perform a lameness investigation; this would be unethical. A lameness investigation is a job for the vendor’s own veterinarian.

Summary of Observations

The veterinarian should summarize the basic assessment of the horse’s physical condition for the buyer. Abnormalities of conformation, clinically insignificant swellings, and any clinical abnormality should be discussed and documented. The initial report should be made verbally to the client or the client’s agent. When dealing with an agent, informing the agent that the client also will be receiving a complete written report is wise. Comments should be as factual as possible, with minimal personal bias, but findings must be interpreted and the risk assessed and documented.

Although the veterinarian is working for the buyer, the veterinarian does have an obligation to the seller. The findings should not be discussed with anyone other than those involved in the sale. With permission of the buyer, the veterinarian can divulge any and all information to the seller.

A written report reviewing the findings of the examination should be provided to the buyer. The American Association of Equine Practitioners has an excellent set of guidelines for reporting the prepurchase examination (www.aaep.org/purchase_exams.htm). This report can serve as documentation of clinically significant findings for future reference.

The veterinarian should advise the buyer about the risks of purchase, without making the decision for the buyer. The veterinarian is not responsible for assessment of the suitability of the horse for a rider or for determining an appropriate value for the horse. However, if the horse is clearly likely to be unsuitable for the purchaser because of temperament or ease of management or riding, the purchaser should be advised accordingly.

Guidelines for Reporting Prepurchase Examinations

The American Association of Equine Practitioners has approved the following guidelines for reporting equine prepurchase examinations. The spirit of these guidelines is to provide a framework that aids the veterinarian in reporting a purchase examination and to define that the buyer is responsible for determining if the horse is suitable. These guidelines are neither designed for nor intended to cover any examinations other than prepurchase examinations (e.g., limited examinations at auction sales and other special purpose examinations such as lameness, endoscopic, ophthalmic, radiographic, and reproductive examinations). Although compliance with all of the following guidelines helps to ensure a properly reported prepurchase examination, the veterinarian has the sole responsibility for determining the extent and depth of each examination. The American Association of Equine Practitioners recognizes that for practical reasons not all examinations permit or require veterinarians to adhere to each of the following guidelines.