Chapter 124Lameness in the Driving Horse

Description of the Sport

This chapter deals with horses used for competitive driving purposes, those driven privately for pleasure, and those used as beasts of burden as a mode of transportation. The sport of driving horses in competition is relatively new and has many variations, requiring different types of horses performing different tasks. Certain breeds or breed types are perfectly suitable for one form of driving sport but not another, and variation in the size, type, and breed of horse used is considerable. Horses and ponies are used, and the term horse is used in this chapter to refer to both, except when specific reference to a pony is required.

In the United Kingdom and Europe there is a much greater availability of a variety of driving competitions than currently exists in North America. The sport is growing in Australia, South Africa, and South America. Pleasure driving includes presentation classes in the show ring and general driving on roads and tracks. Presentation classes are grouped broadly into hackney and nonhackney types, the difference being based on the phenotype of the horse as opposed to a breed registry. A competitor pays close attention to the harness, the attire of the driver, and an appropriate carriage to suit the horse, because judging is subjective and relies on strict adherence to tradition, based on a suitable match of horses and carriage. The horses perform movements requested by the judges, and style and quality of the gaits are scored subjectively. These horses compete at the walk and trot (a park pace being roughly equal to a slow working trot). Pleasure driving events also can include drives at the walk or trot on roads and tracks of up to 5 to 10 miles.

Competitive driving includes combined driving or horse driving trials and scurry driving. Scurry driving is seldom seen in North America but has a strong following in the United Kingdom and other parts of Europe. Scurry driving consists of a single horse (mainly ponies) or more commonly pairs of horses competing over a tight, coned course in a show ring against the clock. The horses and carriages are often small to allow the narrow gates (the gap between a pair of cones) and corners to be negotiated at speed. Horse driving trials are a driven form of horse trials, or eventing, and like its ridden counterpart, driving is a highly athletic, physically demanding sport for the horse and driver.

Driving trials as an international equestrian sport started in 1968, when the Fédération Équestre Internationale (FEI) international rules were drawn up under the instigation of HRH Prince Philip, who was then the President of the Federation. The first international horse driving trials event took place in 1971 in Hungary. Initially the competition was only for horse teams (four-in-hand). A team is composed of four horses, two before two; those in front are called leaders, and those closer to the coach, wheelers. As the sport developed and individuals of more modest means entered the fray, competitions for singles (one horse), tandems (two horses harnessed one behind the other), and pairs (two horses harnessed side by side) rapidly blossomed. These classes were further divided into those for ponies (less than 148 cm or 14.2 hands high) and horses. The sport is now structured at various levels depending on the ability of the driver and horse(s). Disabled driving has recently been introduced. The FEI is responsible for the international rules that cover the World and European championships and selected international events such as the Royal Windsor International Driving Grand Prix. The national associations liaise with the FEI and are responsible for running the national events and championships and producing national rules. Local driving clubs (found in Europe, the United Kingdom, and the United States) also run local events that may differ substantially in standards and requirements of competitors, but they essentially mimic FEI rules. Important events include the Royal Windsor (United Kingdom), Aachen and Riesenbeck (Germany), Breda (Holland), Saumur (France), Waregem (Belgium), St Gallen (Switzerland), and Fair Hill (United States). World championships are held every 2 years for singles, pairs, and teams for horses, and a European championship is held for pony teams. The World Equestrian Games, held every 4 years, which also host World Championships, allow four-in-hands only to compete. The first World Pony Championships (singles, pairs, and teams) were held in Saumur in 2003. Competitions in Europe run from April to September, with championships held toward the end of this period. However, in the last 5 years there has been a growth in indoor driving events, culminating in the FEI World Cup, which is a series of events within Europe. Indoor driving competitions often consist of three phases: precision and paces, cone driving, and time driving through marathon obstacles.

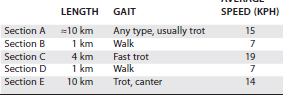

Horse driving trials consist of three phases—dressage, marathon, and cones—usually spread over 3 days, but in lower standard competition all three may take place over 1 to 2 days. The first phase is a driven dressage test, which consists of a set sequence of movements that are judged by a number of officials against a standard of absolute perfection. The test is designed to highlight the obedience, paces, and suppleness of the horse(s), and the skill of the driver in handling of the reins. The second stage is the marathon, which tests the fitness and stamina of the horse(s) and the judgment of pace and horsemanship of the driver. The cross-country marathon can be divided into three or five sections (depending on the level of competition); for each section a maximum and minimum time are allowed (Table 124-1).

The speeds and time allowances are adjusted for different classes, especially ponies. At the end of sections B and D are mandatory 10-minute halts. During the second of these, the horses are subjected to veterinary checks for lameness, injuries, and fitness (respiratory rate, pulse rate, dehydration, temperature, and speed of recovery). Section E has eight obstacles. Each obstacle is made up of a number (up to six) of lettered gates. The aim is to drive through these gates (between white and red markers) within each obstacle in the correct alphabetical sequence in the shortest possible time. Most injuries occur on the marathon, although lameness may not become apparent until later, just before the third phase, the cone competition. The object of the cone phase is to test the fitness and suppleness of the horse after the marathon phase by driving through a course of narrowly spaced pairs of cones (up to a maximum of 20) within an allotted time. Each cone has a ball balanced on top of it that is dislodged easily if the horse or carriage strikes the cone. The winner of the competition is the competitor with the fewest penalty points.

Veterinary inspections of horses taking part in an event also occur before the dressage day, at the end of the marathon, and at the beginning of the cone competition. Lameness at any of these inspections usually leads to elimination from the event, although considerable variation exists in the definition of working soundness among veterinarians, particularly regarding hindlimb problems.

Horses used by Amish and Mennonite sects (United States) as beasts of burden are nearly always Standardbreds or American Saddlebred horses and are driven as singles. The horses are driven when needed, with no structured fitness training, and lameness is common.

Types of Horses Used

The type of horses used for driving varies considerably with the particular form of the sport or use to be undertaken. For pleasure and presentation driving, the type of horse used is related mainly to the size and type of the carriage and the overall effect the driver is trying to convey to the judges (e.g., country or town turnout, meaning an informal or formal appearance of the coach, harness, and driver’s attire). Horses used include Shires, Clydesdales, and Percherons in heavy horse turnouts such as drays; Hackneys (including crosses), Thoroughbreds, and Warmbloods in smart town turnouts; Cobs, larger pony types such as Welsh Cobs, Welsh Section C, Dales, Fells, Fiordlanders, and Friesians in country turnouts; and smaller pony types such as Welsh Mountain Section A, Shetlands, New Forest, and Dartmoor in small carriage turnouts. The aforementioned breeds primarily cover the variety seen in the United Kingdom and Europe. In the United States Warmblood, Warmblood crosses, Welsh, Hackney, Morgan, and Friesians are used most often for pleasure and driving trials. Most presentation and pleasure driving is undertaken with a single horse turnout. The horses range from 4 to 20 years of age, and many have been or are used for other equestrian disciplines. Scurry driving usually involves single or pairs of small ponies or pony-type horses such as Shetlands, Welsh Mountain, New Forest, and Dartmoor. These ponies are often younger than pleasure-driving horses and are less likely to be used for other equestrian sports, except perhaps combined driving trials.

Horses used for driving trials must be older than 4 years of age before they can compete, and records show 19-year-old horses competing at world championship level. Many of the best driving trial horses are 12 to 19 years of age and have been used earlier for other purposes. This long working life and slow introduction to work at a young age, together with little high-speed and more slow-speed conditioning work and regular winter breaks, has a considerable effect on the type of lameness seen in these horses. The types of horses and ponies used vary greatly. In continental Europe, Warmblood breeds are particularly popular; for example, Gelderlanders, Swedish Warmbloods, Dutch Warmbloods, Hanoverians, and Holsteiners, with a modern trait being ever-increasing size. In the United Kingdom less uniformity occurs in the horses used; for example, Hackney crosses, Cobs, Welsh Cobs, Lipizzaners, Lusitanians, Orlovs, and some Warmbloods and Thoroughbred crosses. The most popular ponies used for driving trials in Europe are Welsh Sections A, B, and C, Haflingers, and New Forest crosses.

In the practice radius of one of the authors (KK) is a unique opportunity to observe, evaluate, and diagnose lameness conditions in driving horses used by members of the Amish and Mennonite religious sects as a mode of transportation. Several regions throughout North America have populations large enough to provide a reasonable number of horse owners for which to provide veterinary services. The incidence of lameness is influenced by the necessity of driving reasonably long distances on asphalt surfaces (up to 30 miles [48 km] in one day), with sometimes a single horse pulling a Meadowbrook cart containing up to seven family members. Electricity is not used by the Amish sect and is consequently not available, so a veterinarian must be guided by the ability to palpate precisely and interpret the findings often without the adjunct diagnostic procedures relied on daily, such as radiography and ultrasonography. The veterinarian also faces great pressure because a lame horse may strand an Amish owner.

Training

The training regimen for driving horses varies considerably depending on the type of driving to be undertaken and the level of competition to be attempted. Top-class horse driving trial horses require a regimented fitness program of up to several hours daily, with techniques for such fitness varying from trainer to trainer. In addition some time is spent practicing cone driving, and hazard training through schooling obstacles set up to mimic what is seen in competition. In pleasure or presentation driving, horses normally are worked intermittently, mainly on roads and tracks at the walk and trot, usually in the summer months, with a rest or turnout to grass in the winter. With the introduction of indoor winter competition, winter breaks may be reducing. In scurry driving the training required is more intense, with a combination of regular road work at the walk and trot to increase overall fitness, alongside school and field work concentrating on bending, suppleness, and turning at speed with accuracy. The scurry driving season can extend over longer periods of the year, when competition comes indoors. Amish horses attain a less quantitative level of fitness through irregular use and essentially no training.

Conditioning exercise tends to start in February, aiming for the first events in late April. Competitions are then available almost every weekend (Thursday to Sunday) throughout the summer, culminating in the national and international championships in August to October.

The type or breed of horse used in driving and the way the horse is trained have an important effect on the type and incidence of lameness. Differences in conformation, gait, and size have an influence. Generally, ponies are less likely to develop lameness, are easier to train to fitness, and are more agile. When compared with horses, pony conformation and foot shape are better and they carry less weight. Unfortunately, alongside this general toughness is all too frequently allied a “cussed” temperament. Cob-types are similar to ponies in temperament and hardiness but are heavier and more powerful, often leading to low-grade osteoarthritis (OA) in later life. They often require considerable training to allow the necessary control and obedience to be obtained. Welsh Cobs and hackney-types and crosses have particularly exaggerated natural forelimb actions, which over long periods of use may increase wear-and-tear injuries in the forelimbs such as metacarpophalangeal joint problems. Some of the larger breeds, such as the Warmbloods, have poor conformation, especially in the hindlimbs, such as straight in the stifle and hock, which has a major effect on the incidence of lameness. Most driving horses are not broken to harness until they are 3 to 4 years old and are not worked until they are 5 to 6 years old. Therefore conditions prominent at an earlier age, such as osteochondrosis of the tarsus and stifle, are uncommon.

The incidence of lameness in driving horses is much influenced by a long working life; the training, which is mainly flat work at the walk and trot; the different stresses and strains placed on them by the carriage (increased pressure on the hindlimbs, especially distally); the regular rest periods during the driving career; slow start in life; and whether they have been used for other purposes, previously or concurrently. All of these factors contribute to a low incidence of lameness, especially from fractures or acute soft tissue injuries seen in racehorses, but an increased incidence of low-grade wear-and-tear injuries, particularly of the hindlimb joints. In recent years the increasing competition and prestige at the top end of the sport, particularly internationally, have led to increased demands on horses, less patience to wait for horses to mature or to become seasoned, and consequently more lameness.

Ground Conditions

Training is usually carried out on roads or tracks of varying surfaces, depending on the region and country involved. In the United Kingdom this is mainly tarmacadam roads and firm tracks, whereas in the eastern United States, tarmacadam, dirt, and gravel roads and precut paths through agricultural fields predominate. Training for dressage and cones is usually in grass paddocks, although some drivers have access to all-weather areas. The variable, often hilly terrain in the United Kingdom and United States helps develop fitness. In Europe some of the competitions and areas for training are flat and have a sandy soil, which gives an even, absorbent, good surface for exercise. The firm surfaces on which many driving horses train and work tend to increase concussion to the feet and joints; recent evidence has shown bone density is increased (strengthened) by driving on such surfaces, but firm surfaces are unlikely to prevent injury to tendons and ligaments as was once thought. Repeated concussion over many years may contribute to low-grade joint disease and means that good foot conformation and shoeing are imperative to help offset some of this constant trauma. The variable and unpredictable ground conditions present on marathon courses contribute to injuries to joints, such as the fetlock, and to ligaments and the digital flexor tendon sheath (DFTS).

Conformation

The huge variety of breeds and types of horses used in driving means that no particular traits of conformation have been established as representative of this type of work. Many of the Warmbloods, which are the most common breeds on the continent of Europe and are now becoming so popular elsewhere in the world for riding and driving, have a conformation that appears to predispose them to OA of the distal hock joints. The hindlimbs are often straight through the hock and stifle, but some horses are sickle hocked and cow hocked. There is a high prevalence of osteochondrosis in Warmbloods, especially of the tarsocrural and stifle joints, which may manifest itself later in the working life of the horse. The headlong dash in recent years for bigger and stronger Warmblood driving horses has in our opinion led to a heavier, less agile horse, often with small feet and limited bone, which cannot help the horse cope with work over the many years that the horse is driven. Foot conformation in some of the carriage breeds, such as the Hackney, Orlov, Gelderlander, and Lipizzaner, can be upright and boxy, which may decrease concussion protection by the foot and increase trauma reflected up the limb. Many of the native breeds or crosses have good conformation and inherent limb soundness, which is reflected in their low level of lameness. The exception to this statement is the pleasure or presentation pony that is worked irregularly and kept at grass in the summer. The overweight (show condition) nature of these ponies and the access to large amounts of grass predispose them to laminitis, which more reflects owner management than suggests inherent unsoundness.

Lameness Examination

Examination of lameness in the driving horse differs little from the standard approach. The major objectives are to decide if the horse is lame, to determine which limb or limbs and which portion or portions of the limb(s) are affected, and to determine a pathological process. This process is complicated in a driving horse, particularly as the horse ages, because of the possibility of old or unimportant lesions and the low-grade and often bilateral nature of some causes of lameness. Further problems are related to intermittent or variable lameness. Identification of lameness is more difficult in a driving horse when being driven, especially lameness in a hindlimb, than in a ridden horse.

The history should consist of typical questions asked before any standard lameness evaluation—for example, how the lameness was first recognized, what the duration of the lameness has been, whether the lameness is worse on hard or soft ground, and whether the horse has responded to any treatments used. In addition, because driving horses are exercising between two poles that are parallel to the ground, straightness is generally fairly easy for the driver to observe. Is the horse resting one hip on the right or left shaft? Is the horse leaning more on one rein than the other? With pairs and four-in-hand, is one horse taking more of the workload, indicating unwillingness of the other horse to pull an equal load? Have any changes in tack or harness been made? The veterinarian should observe the stance and attitude of the horse, areas of muscle atrophy, limb and foot conformation, and the presence of swellings before assessing the horse moving in hand at the walk and trot on a hard, flat surface. Examination in harness and carriage is rarely useful, because lameness is sometimes less evident while the horse is pulling, rather than moving freely and without restriction on a lunge line. When a driver or trainer feels that the lameness for which the horse is being presented is observed only when in work, that is, driven, seeing the horse in harness then may be necessary. Standard flexion tests of the forelimbs and hindlimbs are useful, but as a horse ages the likelihood of a positive result in an otherwise working, sound horse increases. Exercise on the lunge or in hand on a circle is helpful in horses with bilateral or mild lameness. Exercise on different surfaces (hard and soft) and when possible on a slight incline uphill and downhill can be useful.

Identification of the affected lame limb(s) should be followed by detailed palpation and manipulation of the limb(s), with the limb bearing weight and in a flexed position. Assessment of any swelling by digital palpation and manipulation of the limb(s) to determine whether pain can be elicited can help to differentiate old, clinically insignificant lesions. In older horses distention of fetlock and tarsocrural joint capsules and DFTSs is a common, clinically insignificant finding. Skin scars and areas of fibrosis from previous trauma may further complicate the localization of the site of pain causing lameness. Careful examination of the foot with hoof testers is important. The use of diagnostic analgesia is considered vital to rule out incidental lesions or previously managed chronic problems.

Diagnostic Analgesia

Many of the causes of lameness in driving horses are related to chronic wear-and-tear injuries in one or more joints. Distention of a joint capsule or DFTS can be an incidental finding. Localization of pain by a logical system of regional analgesia is central to our approach to lameness diagnosis and is particularly useful in horses with bilateral or multiple limb lameness, because such an approach allows the effect on the gait of one or more of the lame limbs to be removed, allowing identification of additional lame limb(s). In most horses localization of pain is initially undertaken by a sequence of perineural analgesic techniques beginning distally and moving proximally in a logical manner. In the forelimbs the sequence is palmar digital; palmar (abaxial sesamoid); low palmar and palmar metacarpal (four point); high palmar (subcarpal); and median, ulnar, and musculocutaneous. In the hindlimb the sequence is plantar (abaxial sesamoid); low six point; analgesia of the proximal aspect of the suspensory ligament (SL) (see Chapter 10 for numerous described techniques); intraarticular blocks of either specific joints of the tarsus or suspected stifle joints; and then tibial and fibular (peroneal) nerve blocks. Nerve blocks of the antebrachium or crus are useful when the veterinarian is uncertain if the lesion is above or below midlimb. Once that has been determined, more specific blocks may be planned proximally or distally as needed. If the veterinarian suspects a particular site, performing an intraarticular block at that site first may be more efficient. It may be necessary to perform intraarticular blocks after perineural analgesia. Sites for intrasynovial analgesia are prepared aseptically (with or with out clipping, at the discretion of the veterinarian), and fresh bottles of mepivacaine or bupivacaine, needles, and syringes are used. Gloves are mandatory for intrasynovial techniques. Assessment of response can be difficult in horses with mild or intermittent lameness or when several painful sites exist. The veterinarian should be as certain as possible of the degree of improvement in the lameness, but unfortunately this is sometimes equivocal. In a driving horse the most common intrasynovial structures injected are, in the forelimb, the distal interphalangeal (DIP), proximal interphalangeal (PIP), and metacarpophalangeal joints and the DFTS; and, in the hindlimb, the PIP, metatarsophalangeal, tarsometatarsal (TMT), centrodistal, and tarsocrural joints and the DFTS. Local infiltration of local anesthetic solution around areas of possible damage, such as periosteal reactions and ligament insertions, may be helpful in horses with specific injuries.

Imaging Considerations

Many causes of lameness in a driving horse, especially in older horses, are related to problems in the distal aspect of the limb and the hock joints. Considerable variation in the radiological appearance of these structures can occur, representing normal anatomical variability, old injuries, incidental findings, or wear and tear. Only by localizing the site of pain to a particular joint by intraarticular analgesia is interpreting these findings possible. Standard radiographic images are obtained. Upper limb injuries are often induced by trauma, are not localized easily by diagnostic analgesia, and are difficult to examine with small x-ray machines. Ultrasonography is particularly useful in examining some of these injuries, not only to differentiate the soft tissue components (e.g., hematoma, muscle injury, edema, and wounds), but also to examine the cortical outline of the bones in the proximal aspect of the limb (shoulder and stifle regions) for evidence of fractures or other damage. Comparison with the opposite limb is helpful in determining what is normal in these areas.

Ultrasonography is essential for examining the DFTS and associated structures and for definitive diagnosis and monitoring of desmitis of the SL or the accessory ligament of the deep digital flexor tendon (ALDDFT). It may also be useful for evaluation of joints for detection of collateral ligament or joint capsule injury and identification of periarticular modeling or articular cartilage damage.

Difficulties in Diagnosis

The most difficult problem in diagnosing pain causing lameness in a driving horse is an intermittent, often low-grade lameness that may flare up with increased exercise or competition. Many lame driving horses have bilateral hindlimb problems, often with several sites of pain contributing to lameness. If making progress in these horses by standard examination techniques is impossible, scintigraphic examination may be useful. The advantages of scintigraphy include the ability to cover many areas of the body (forelimbs and hindlimbs, back and pelvis) at one session, the noninvasive nature of the technique, and its use to monitor healing. The disadvantages include cost, lack of local availability, and lower sensitivity of the technique in localizing chronic sites of inflammation compared with acute injuries. Several sites may be detected as having increased radiopharmaceutical uptake, and other techniques, such as local analgesia, are necessary to assess clinical significance. Making a definitive diagnosis is not always possible, but it is important to treat what is diagnosable or visible and to monitor the horse’s progress carefully during convalescence. A reassessment of the horse at regular stages may cast further light on the problem. We frequently tell clients that the best option is to treat what we are able to identify and monitor the progress of such treatment through periodic reassessment. Rest may be easy to accomplish in driving horses because they have a long working life, and in pairs and teams a spare horse may be available to take the lame horse’s place, allowing competition to be continued.

A problem occasionally encountered in lameness from harness and carriage use is an abnormal gait, often intermittent, seen only while the horse is working in harness, usually with the carriage. Lameness often is manifested at the collected trot in the forelimb, and an extra lift in the shoulder movement during protraction is apparent. Usually only one forelimb is affected. The horse appears normal at the walk and extended trot, and the problem is not exacerbated by exercise. The actual diagnosis of this condition remains obscure, but one possible theory revolves around the effect of a neck collar on the action of the scapula while the horse is in harness: a mechanical interference. In some horses, changing from a neck collar to a breast band harness appears to stop the problem.

Shoeing

Most driving horses are shod conventionally, with few special techniques or shoes. Many are shod with flat, fullered shoes set rather short and tight at the heels to minimize interference injuries to the horse and the other member(s) of the pair or team. Other reasons for such shoeing given by farriers and owners include minimizing shoe loss in the varying surfaces of the competition and preventing inadvertent removal by the wearer or another horse by standing on the shoe. Short-shoeing a horse, with a tight fit in the heel, exacerbates poor foot conformation, whether the horse has upright, boxy feet or long-toed and low, weak-heeled feet.

The use of studs and occasionally calks, especially in the hind feet, is common in an attempt to increase grip in the marathon phase of competition. In the teams, the wheelers, where the power is mainly delivered, often have studs or calks. If studs have to be used, we prefer to see them put in only for the marathon and, if possible, only for the obstacles. The extra grip studs can give may lead to ligament or joint damage, particularly in the lower limb. The use of studs or calks all the time, especially on hard tracks and roads, increases heel trauma and changes the forces transmitted up the limbs. Unilateral studs and calks are not acceptable, and their use should be actively discouraged.

Ten Most Common Lameness Conditions

A 15-year retrospective study of the clinical practice of one of the authors (KK) led to the formation of the following list of common lameness conditions, in order of incidence. Some variation in incidence occurs from leaders to wheelers in four-in-hand teams and in other countries, such as the United Kingdom.

Diagnosis and Management of Lameness

Suspensory Desmitis

Desmitis of the SL, both body and branches, is common, particularly in Amish and Mennonite carriage horses. Seventy percent of the Amish carriage horses are Standardbreds, nearly all of which have raced previously and have preexisting chronic, healed, or healing suspensory desmitis. Forelimbs (80%) and hindlimbs (20%) are affected. Body and branch lesions occur with similar prevalence in forelimbs, but branch injuries predominate in hindlimbs.

Suspensory desmitis may cause an acute-onset, moderate lameness, but often a low-grade insidious lameness is reported by the owner or driver. There is often considerable swelling and inflammation associated with the SL. Horses with branch lesions especially have a positive response to a lower limb flexion test. Diagnosis usually is based on clinical examination and is confirmed by ultrasonography, but in some horses diagnostic analgesia is required to confirm that the SL is the source of pain.

With branch lesions radiological examination of the proximal sesamoid bones (PSBs) and splint bones is required to identify concurrent fractures or sesamoiditis, which influence prognosis. PSB fractures usually are seen in Standardbred horses that have raced previously and were retired with a fracture, pain from which becomes apparent after a second career as an Amish driving horse. Amish and Mennonite horses with a less-than-good prognosis may be culled.

Rest is essential. The duration is determined by improvement in lameness, reduced sensitivity on palpation, and improvement in fiber pattern assessed by ultrasonography. In the initial, acute stages, cold hosing, icing for a few days, and support wrapping are recommended. The combined oral use of dexamethasone and a diuretic is helpful in decreasing inflammation and filling without masking pain. It is important to provide appropriate palmar or plantar support, and if necessary an egg bar shoe is used to increase the weight-bearing surface.

In horses with the most severe injuries, and in situations in which economics does not play a role in selection of treatment, a more aggressive approach may be considered. Very good results have been obtained with surgical treatment of horses with large core lesions in the body of the SL. After perineural analgesia and localization of the core lesion by ultrasonography, we use a sharpened teat bistoury to enter the core lesion with the limb bearing weight. A rigid 18-week slow progressive exercise schedule is then employed. Alternatively, intralesional injections of autologous platelet-rich plasma (PRP) or stem cells can be performed. Several different commercial kits are available for retrieval and harvesting of biological material. We are encouraged by the results to date, but the number of driving horses managed using these techniques is insufficient to report the level of success.

Some clients prefer to turn out a horse with suspensory desmitis rather than adhere to a structured rehabilitation. Our impression is that lesions heal more slowly, often with less acceptable cosmetic results, compared with horses in which controlled exercise is used. Horses with branch injuries are treated conservatively with a long, slow progressive exercise schedule, with periodic ultrasonographic monitoring. Therapeutic ultrasound treatment also is recommended.

Prevention of suspensory desmitis is achieved primarily by selecting well-conformed horses with a good hoof-pastern axis and good feet and continually reassessing hoof balance, the adequacy of heel support, and the angle of the pastern relative to the limb conformation.

Foot Lameness

Foot lameness is common in driving horses and is traumatic, degenerative, or inflammatory. Lameness varies from simple trauma (puncture wounds and bruises) to infectious conditions such as thrush, degenerative conditions such as navicular syndrome, and a host of lesions caused or affected by quality of shoeing.

Carriage horses receive a moderate amount of direct trauma resulting in wounds to the digit. The lack of available prepared and manicured training surfaces often necessitates fitness work on gravel roads and through streams and wooded areas, and solar punctures by stumps or sharp objects are not uncommon. Injuries to the coronary region of horses in pairs and four-in-hand occur when driving conditions are difficult, as in the hazards, when one or more horses may be stepped on by an adjacent horse.

Although wounds of the coronary band are generally obvious, a puncture of the sole may not be readily apparent. A horse with a puncture may or may not be lame at the time of injury. The excitement of competition allows horses to continue without overt signs of discomfort, even with frank injury to the sole. Once back in the stable or sometimes the following day, lameness becomes apparent. Many wounds of the sole and frog are difficult to see, and they can be missed easily. Frog and sole tissue tends to close over the entry site, particularly if the offending object was sharp. If foreign material remains in the foot, severe lameness is usually present. We recommend being very aggressive with “unroofing” sole or frog puncture sites in horses with severe lameness, because it may be the only way to tell if vital structures are contaminated, and removal of organic material is imperative. Most horses respond well to curettage and soaking in antiseptic solutions, but protracted lameness is usually a sign of infection. Contrast radiology is useful to detect direction and depth of a tract. When a veterinarian cannot determine if vital structures are involved, surgical exploration or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination may be indicated.

Bruises and corns are diagnosed by localizing pain to the sole or heel, evaluating the history, ruling out other causes of foot lameness, and identifying areas of solar discoloration. Treatment for bruising is directed at protecting the sole. In susceptible horses with a chronic tendency toward bruising, use of foot soaks or preferably packing gel with dimethyl sulfoxide with an overwrap frequently is indicated for flare-ups. Horses with corns require changes in shoeing to relieve pressure on the heel and constant monitoring of the heel growth to discourage an underrun, rolled in heel.

Synovitis of the DIP joint occurs as an acute or, less commonly, as a recurrent condition. Effusion of the DIP joint and lameness generally are exacerbated by distal limb flexion. Diagnosis is confirmed by intraarticular analgesia. Treatment consists of phenylbutazone (2 g sid) or flunixin meglumine (500 mg sid) for several days, icing of the digit, and intramuscular administration of a polysulfated glycosaminoglycan (PSGAG), with or without intraarticular administration of hyaluronan or corticosteroids.

Navicular syndrome may be more prevalent in carriage horses of certain breeds. The European Warmbloods, particularly the heavier horses, appear to be at risk. Navicular syndrome is nearly nonexistent in driving ponies. Horses with navicular syndrome have an insidious lameness that usually resolves with palmar digital analgesia. Occasionally a horse has sudden onset of moderate-to-severe lameness without any history of a chronic problem. These horses may have dramatic lesions apparent radiologically without a reasonable explanation for why the lameness occurred suddenly rather than gradually. A critical evaluation of hoof balance is important, and we recommend using bar or egg bar shoes. Very good results have been obtained by intrathecal injection of the navicular bursa with hyaluronan and triamcinolone acetonide (4 to 6 mg) along with improved shoeing. Horses with more pronounced lameness may also be treated with phenylbutazone (1 to 2 g orally [PO] sid).

The greatest number of carriage horses with foot pain fit into a broad category of palmar foot pain (also see Chapter 30). Lengthy drives on hard surfaces result in chronic contusions to the hoof capsule and subsequent lameness. Palmar foot pain often is correlated with the degree of work the horse is undertaking currently and may occur seasonally in susceptible horses. Lameness varies from slight to moderate and is exacerbated by circling on hard ground with the affected limb on the inside of a circle. Hoof tester examination may reveal pain from the medial or lateral sulcus across to that quarter, but a large number of horses have no reaction. Lameness is eliminated by perineural analgesia of the palmar digital nerves. Intraarticular analgesia of the DIP joint and intrathecal analgesia of the navicular bursa ideally should be performed to rule out these structures as sources of pain. Radiological examination usually is unrewarding.

Assessment of hoof balance and shoeing is necessary, and until any imbalance has been corrected, recommending other therapies is pointless. We have had good results from increasing the length of support or ground surface in the dorsal or palmar direction of the hoof, without any other therapy. Many horse owners do not understand when instructed to move the weight-bearing surface farther palmarly, and they simply raise the heel. Talking directly with the farrier and providing explanatory diagrams to the client are worthwhile. If the heels are too weak or inadequate to allow for corrective trimming, using egg bar shoes until heel growth is adequate may be necessary.

Distal Hock Joint Pain

OA of the distal hock joints is common, particularly in older and larger horses (>10 years old). Many of these horses are not presented by the owner or driver as overtly lame but with a history referring to lack of performance or action, stiffness, back problems, or poor bending. Some horses with OA, especially from teams, are not identified until veterinary inspections at events. Many older driving horses, particularly those in horse driving trials at a high level, have an uneven hindlimb gait, especially when trotted in hand, and have a positive response to upper limb flexion tests. The horse often is said to warm or work into its work (warm out of lameness), and owners do not request investigation. A high percentage of these horses have low-grade OA of the distal hock joints. In some horses acute lameness or gradual worsening of lameness (often described as unilateral lameness by the driver) leads to lameness investigation. In the Warmblood breeds an earlier incidence of this problem has become apparent in recent years, with horses of 5 to 8 years old showing severe OA and even ankylosis of affected joints. Many have poorly conformed and small hocks, and in some OA appears to be a sequela to developmental orthopedic disease in a young, growing horse.

Diagnosis is based on clinical examination, intraarticular analgesia, and radiology. Many horses have bilateral lameness, with one limb worse than the other, and evidence of gluteal muscle atrophy. Poor hock conformation (sickle hocked, straight, or cow hocked) predisposes some horses to OA. Shoe and hoof wear may indicate toe dragging or abnormal lateral breakover. Swelling may be palpable or visible at the seat of spavin. Tarsocrural joint distention is a common incidental finding, but it may indicate proximal intertarsal (talocalcaneal-centroquartal) joint involvement. The gait often is characterized by reduced foot flight arc and hock flexion, leading to toe dragging, and adduction of the limb medially underneath the body to land and then breakover laterally. On the lunge, lameness of the inside hindlimb may be worse, with shortening of the cranial phase of the stride and a tendency to fall toward the handler. Bilateral lameness is common, although one limb is often worse, leading to a choppy or stilted gait.

Flexion tests of the upper hindlimb are often positive bilaterally, but the response varies enormously depending on the stage and extent of the disease and the individual horse. Positive flexion test results in the hindlimbs of older driving horses are common, even in the absence of lameness.

Initially, lameness can be localized to the hock region using perineural analgesia, although intraarticular analgesia is more specific. Previously the centrodistal and TMT joints were blocked separately, but more recently only the TMT is blocked, on the basis of recent research confirming the high rate of diffusion of mepivacaine between the two joints.

A poor correlation exists between the degree of lameness and the extent of radiological abnormalities. Scintigraphic examination may be indicated in the absence of radiological abnormalities.

Treatment depends on a variety of factors including the degree of lameness, other concurrent causes of lameness (e.g., back problems), the type and extent of radiological abnormalities, the age of the horse, the level of work, the competition undertaken, the time and cost constraints, and the response to previous treatment. Conservative treatments often are used when financial constraints exist, when lameness is mild, or when radiologically the disease is advanced, or simply to assess the effects of treatment before more radical therapy is considered. Surgical treatments involve the willingness of the owner to make the financial investment and subject the horse to the risk of general anesthesia. We usually assess all aspects on an individual basis before embarking on a standard treatment plan, involving three monthly clinical and radiological examinations.

In general, because of the low-grade and chronic nature of the complaint in driving horses, a horse initially may be treated conservatively with corrective shoeing (graduated toe heel shoe, rolled at the toe, with or without lateral extension), a controlled graduated exercise program (up to 90 minutes) placing an emphasis on walking and trotting in a straight line (ridden or driven), and oral medication with variable levels of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (usually phenylbutazone) to control pain and encourage a more normal action. Many driving horses make considerable clinical progress with this regimen, but few high-level driving trial horses are able to return to competition quickly. Resolution of lameness may take up to 18 months and in some horses never happens if conservative treatments are used. Predicting the course of the disease and ultimate result in any one horse is difficult early and requires consideration of all the clinical and radiological findings. Many horses improve, but they do not become sound and have minimal progression of radiological abnormalities over 6 to 12 months. Horses with more obvious lameness, or those that are unable to cope with exercise with orally administered phenylbutazone, may be candidates for intraarticular injections with long-acting corticosteroid preparations (10 mg triamcinolone acetonide or 40 mg methylprednisolone acetate per joint). This may result in improvement for 3 to 6 months, and repeated injection usually is required. The use of NSAIDs or corticosteroids is not allowed in official competitions, and drugs must be withdrawn according to the manufacturers’ recommendations before any competition. The use of tiludronate has increased with mixed results. Pentosan polysulfate (Cartrophen) is used by some clinicians, but there is controversy over its efficacy, and the drug is not licensed for use in the horse in Europe.

Arthrodesis is used in horses that fail to respond to conservative or intraarticular treatment or are in too much pain to achieve ankylosis by exercise, and when time to return to performance soundness is important. In horses with minimal radiological changes, intraarticular injection of sodium monoiodoacetate is performed using general anesthesia. In horses with more advanced radiological abnormalities or those in which monoiodoacetate has failed to achieve ankylosis, surgical treatment using three drill holes is used in each joint. Controlled exercise postoperatively is essential for success with either treatment. Although many driving horses with OA of the distal tarsal joints are useable with treatment, complete resolution of lameness is unusual.

Exertional Rhabdomyolysis

Carriage horses have isolated episodes of tying up during competition or strenuous exercise, and this is a true exertional rhabdomyolysis. Competition horses may develop mild signs of muscle stiffness affecting the hindquarters, during or at the conclusion of an exertional session, such as the marathon. The condition may become apparent in the 10-minute box, during the formal veterinary examination section, or before the marathon course. Clinical signs are invariably subtle and may be interpreted as fatigue by an inexperienced competitor. Affected horses should be withdrawn from the competition to avoid further skeletal muscle damage. Treatment should include administering antiinflammatory drugs and low doses of acepromazine (5 to 25 mg total dose) and ensuring adequate hydration. Horses should not be walked out of the stiffness and should be moved by trailer from the 10-minute box to a treatment stall.

To prevent further episodes, the feeding up to and including a competition and a horse’s fitness program should be evaluated and amended as necessary. Teaching drivers how to assess a horse’s fitness by measurement of temperature and pulse and respiratory rates on the stress days of training sessions is particularly valuable.

Acute, severe rhabdomyolysis (tying up) also occurs in horses driven by the Amish and Mennonites. These are frequently emergency situations. Horses have true, severe exertional rhabdomyolysis and are often in recumbency when examined. The clinical signs in nonrecumbent horses are extreme muscle stiffness and swelling over the topline and gluteal muscle groups, increased heart rate, sweating, and coliclike symptoms. The history is consistent: the horse became stiff while being driven, but the driver needed to continue to a destination and may have been driven another 1 to 15 miles [1.6 to 24 Km]. The condition in colloquial Amish terminology is referred to as kidney shot.

Rehydration and controlling pain and shock are imperative. Tranquilizers are particularly helpful, and measurement of packed cell volume and total protein concentration is useful for monitoring hydration. Measurement of creatine kinase may be useful prognostically in recumbent horses, although the initial response to treatment and the ability to get the horse on its feet are primary factors in determining whether the horse can be saved. Creatine kinase concentrations are often 400,000 to 800,000 IU/L (normal 130 to 400 IU/L), and we have treated horses successfully with levels up to 600,000 IU/L. Without prompt emergency attention, nearly all of the more severely affected horses die or are ultimately humanely destroyed. Most horses that remain recumbent after 24 hours are lost.

Horses are viewed by Amish farmers as utilitarian and necessary for transportation, and prevention of fatal exertional rhabdomyolysis is not necessarily easy. Owners should be advised of the need to match exercise with the intake of concentrates. If possible, the horse’s entire body can be clipped if the onset of summer or warm weather is sudden or the winter coat is still present. Clipping can be done using a gas-powered generator for the clippers. Clipped horses have less risk of severe dehydration, and a clipped horse apparently is less prone to rhabdomyolysis than a hirsute horse.

Tenosynovitis of the Digital Flexor Tendon Sheath

Tenosynovitis of the DFTS is a common cause of acute hindlimb lameness. Often extreme swelling of the DFTS occurs and is turgid and firm, which contrasts to chronic, benign distention of the DFTS in which fluid in an overly stretched sheath can be balloted from side to side.

With horses with acute tenosynovitis there is a substantial response to lower limb flexion, and in some horses (5%) a non–weight-bearing lameness develops. Using perineural analgesia is unnecessary, but intrathecal analgesia using 6 to 10 mL of mepivacaine can be used to confirm the source of pain. Synoviocentesis is best performed distal to the fetlock and is facilitated by applying a disposable elastic bandage around the distal metatarsal region to push the fluid into the distal outpouching of the sheath on the plantar aspect of the pastern (Figure 124-1). Once the sheath has been entered, an assistant cuts off the bandage, and local anesthetic solution is injected.

Fig. 124-1 A, Application of a pressure bandage isolates fluid in the distal, plantar outpouching of the digital flexor tendon sheath, facilitating synoviocentesis. B, An assistant cuts the compression bandage during injection.

Radiological examination is usually negative, but is necessary to be certain that no unexpected lesion is missed. Ultrasonographic examination is essential to determine if tenosynovitis is associated with a lesion of the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT), which requires a longer convalescence, and horses have a more guarded prognosis than those with primary tenosynovitis.

Treatment is based on reducing inflammation and controlling exercise. Uncontrolled turnout results in prolonged healing, and stall rest followed by walking in hand is preferable. A horse with an acute injury is treated with icing for 40 minutes twice a day, for 2 to 3 days, and orally administered NSAIDs. Intrathecally administered hyaluronan is beneficial. Caution should be exercised in the use of corticosteroids, which may provide temporary relief and often give the client a false sense of security regarding the rate of healing. Isoflupredone acetate is recommended, is short acting, and may control the acute flare-up without having any long-term effect that makes monitoring progress difficult. Methylprednisolone acetate lasts at least twice as long and may predispose the horse to develop dystrophic mineralization in the sheath. We have had better long-term results with conservative medical management than with surgical treatment by desmotomy of the plantar annular ligament.

Prevention of tenosynovitis and tears of the DDFT is difficult, because most injuries are acute and unforeseeable, occurring during strenuous exercise. A team horse previously used as a wheeler may be better placed as a leader. The foot should be kept well balanced, with a full-fitting shoe providing adequate plantar support.

Chronic Osteoarthritis of the Lower Limb Joints

Many driving horses develop chronic OA of the DIP, PIP, and metacarpophalangeal joints as a result of wear and tear because of the work they undertake, the length of time they are used, and other factors such as conformation, foot shape, and shoeing. Radiological examination of these joints, especially in the hindlimbs and in larger horses, often reveals a variety of intraarticular and periarticular abnormalities that may be associated with lameness. Older driving horses often live with low-grade hindlimb gait abnormalities associated with low-grade joint pain. This low-grade, chronic, and often multiple leg or multiple joint pain can be exacerbated by excessive or different exercise regimens, leading to acute flare-ups, increased lameness (often unilateral), joint flexion pain, periarticular heat, and joint swelling. Radiographs obtained at this time reveal little more than the preexisting abnormalities. Intraarticular analgesia may be essential to localize the pain causing lameness, but multiple limb and joint involvement can make localization difficult. Nuclear scintigraphy may be helpful, but it is expensive, and often it is used only after early treatment has proved unsuccessful.

Treatment of horses with acute flare-ups of OA involves cold therapy such as cold hosing or ice packs, compression bandaging, systemic NSAIDs, topical applications of various antiinflammatory substances, and intraarticular or systemic medications such as corticosteroids, hyaluronan, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein (IRAP), and PSGAGs. Rest and a controlled, graduated return to exercise are important. Management of horses with chronic OA involves a careful review and possible modification of the horse’s work program, judicious use of NSAIDs, physiotherapy techniques such as laser or ultrasound treatment, and systemic medication with hyaluronan or PSGAGs. The prognosis varies enormously depending on the severity and extent of the problem, the way in which the individual horse responds to pain, and the level of work required to keep the horse sound and competing. In many horses, if the hindlimbs are affected and especially if the condition is bilateral and the horse is part of a pair or team, then the chronic low-level lameness is not observed, is undiagnosed, or is ignored. An acute flare-up may lead to recognition of the problem and diagnosis. Prognosis for horses with the first acute flare-up is reasonable, but those with further occurrences warrant more aggressive management, which if unsuccessful worsens the overall prognosis.

Stifle Lameness

A definitive diagnosis of the cause of stifle pain in driving horses is often difficult to determine. Most horses with stifle lameness are wheelers of a four-in-hand or one of a pair. It is generally accepted that wheelers supply 60% of the workload in pulling, which may affect the incidence of stifle lameness. Lameness is usually acute in onset and unilateral, with no stifle effusion or other localizing clinical signs. Stifle flexion may cause more obvious accentuation of lameness than other hindlimb flexion tests. Lameness is improved by intraarticular analgesia.

Radiographs uniformly are negative. Ultrasonographic examination may sometimes reveal a lesion, but in more than 80% of horses no cause of pain can be identified. However, with digital ultrasonographic imaging and improved operator skill the likelihood of establishing a diagnosis may improve. Arthroscopic exploration may be warranted, but this is expensive, and only a limited part of the stifle can be assessed. The prognosis generally is guarded for horses with a known meniscal or cruciate ligament injury and for those without a specific diagnosis. The best results have been achieved after intraarticular treatment with hyaluronan, combined with systemic administration of PSGAG and rest or rigidly controlled exercise, walking in hand.

We recommend that horses not resume work until 60 days after complete resolution of lameness and when they no longer manifest a positive response to stifle flexion.

Direct Trauma

Traumatic injuries to the limbs and body of a driving horse are common.

Interference Injuries

Distal limb lacerations of varying severity are common, especially in horses that are part of a team, particularly in combined driving, and are caused by overreaching (forelimbs) or by interference from other horses. The most common lesions involve the heel and coronary band (Figure 124-2), although wounds to the midpastern and distal palmar (plantar) aspect of the metacarpal (metatarsal) region occur frequently. Many wounds are superficial and consist only of contaminated skin, but it is essential to check for injury to the digital flexor tendons and the DFTSs, joint integrity, and damage to the coronary band. The horse should be restrained properly, the affected area clipped and vigorously cleaned, and the damage assessed before medical or surgical treatment is initiated. In some horses detailed examination using digital palpation with sterile gloves, radiography, ultrasonography, and even surgical exploration may be necessary. Early and aggressive treatment may improve the prognosis considerably in the short and long term.

Injuries to the Brisket, Lower Neck, Antebrachium, Stifle, and Crus

Injuries usually occur during the marathon phase of driving trials, especially in the obstacles, or after runaways and accidents in any driven horse. The tendency of some drivers in combined driving in recent years to drive the carriage as a battering ram through the obstacles has increased the incidence of these injuries. Skin lesions occur, especially in the brisket and caudal aspect of the neck and upper forearm regions, and can range from full-thickness lacerations to mild hair loss and deeper bruising (Figure 124-3). In some horses little is visible externally except mild swelling to suggest the site of impact. Stiffness or lameness often develops several hours later. Severe trauma, particularly involving broken shafts or obstacles, can lead to life-threatening injuries to the chest, abdomen, or vital vascular structures.

Fig. 124-3 A severe traumatic injury to the upper forelimb and brisket regions caused by a collision with an obstacle in the marathon.

The injured area should be examined carefully, particularly when lacerations are present. In these, thorough lavage and cleaning, followed by digital exploration using sterile gloves to assess for additional deeper damage, are essential. Surgical repair may be necessary. Horses with blunt soft tissue damage and bruising benefit from light walking in hand, cold therapy, topical and systemic antiinflammatory medication, and physiotherapy techniques.

Desmitis of the Accessory Ligament of the Deep Digital Flexor Tendon

Desmitis of the ALDDFT is a common cause of forelimb lameness. Older horses, including ponies, are more likely to be affected, and injury can occur at exercise or during turnout. Onset is usually acute, with unilateral forelimb lameness occurring during or immediately after exercise. Swelling of the ALDDFT occurs with edematous swelling of the surrounding soft tissues. In horses with severe desmitis, periligamentous hemorrhage can occur. Palpable pain is rare, but heat usually is apparent.

Ultrasonographic examination is used to determine the extent of injury. Diffuse lesions are more common than focal core lesions. Damage to other tendon structures is uncommon, but adhesions to the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) or DDFT do occur, particularly in horses with chronic recurrent injuries.

Treatment of horses with acute injuries includes cold therapy, compression bandaging, box rest, and topical or systemic antiinflammatory medications. We regularly recommend the use of systemic PSGAG therapy and therapeutic ultrasound physiotherapy from 7 days after injury. Graduated walking in hand is encouraged from 7 days after injury, increasing in duration up until 12 weeks, when limited free exercise is allowed. Ultrasonography is essential to determine when healing is sufficient to allow exercise to begin. A total convalescent period of 6 to 15 months may be required. Some injuries, particularly in older horses, do not heal satisfactorily. Occasionally horses with chronic injuries with adhesions have been treated by desmotomy of the ALDDFT, but the prognosis for return to full soundness is guarded. Recently a small number of horses with severe injuries have been treated with PRP, but it is too early to evaluate success.

Superficial Digital Flexor Tendonitis

Superficial digital flexor tendonitis is not common in a driving horse, although the condition is seen occasionally as a flare-up of a lesion sustained previously in another discipline, or in wheelers when the going during the marathon phase has been soft and deep. Most lesions are in the distal half of the metacarpal region and are generally mild. Diagnosis is based on clinical and ultrasonographic examinations. The prognosis for return to full work as a driving horse is generally good, because most of the injuries are mild and the type of work to be undertaken is usually slow.