10 Relaxation massage

Stress

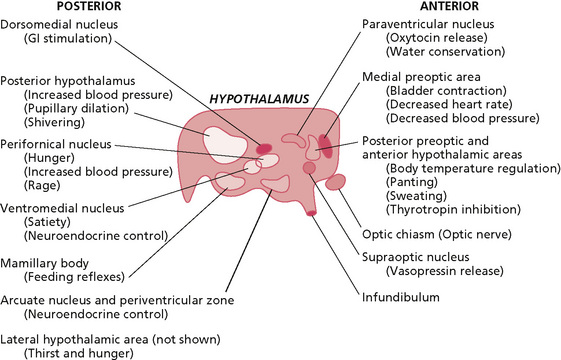

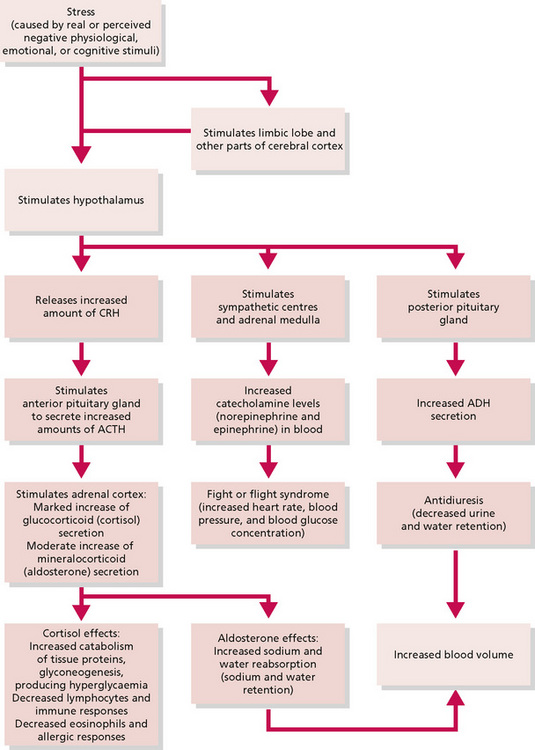

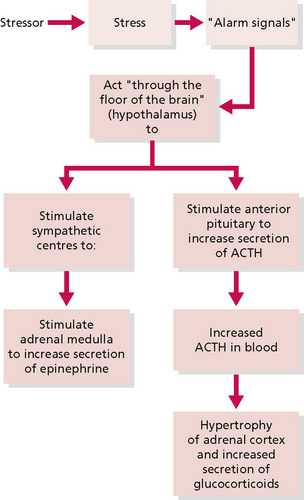

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) was discussed in Chapter 3 in connection with the reflex effects of massage. That discussion is extended here, applied specifically to stress and autonomic arousal. The relevant function of the ANS to relaxation massage is that when an individual experiences severe fear or pain, or has a strong emotional reaction, the hypothalamus is stimulated to transmit impulses to the spinal cord which cause a sympathetic discharge, resulting in the alarm response, or general adaptation syndrome (Seyle 1982) (Fig. 10.1). This is the protective mechanism which prepares an animal or human for ‘flight or fight’, to ensure that, whichever of these actions is chosen, the animal is physiologically prepared for vigorous activity. The changes include an increase in blood levels of glucose, cortisol, adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine), and an increase in blood pressure, blood flow to skeletal muscles, muscle tone and heart rate—the sympathetic stress response (Figs. 10.2 and 10.3).

Figure 10.1 • • Control centres of the hypothalamus.

Reprinted from Textbook of Medical Physiology 8e, Guyton (1991) with permission from Elsevier.

Figure 10.2 • • Current concepts of the stress syndrome.

Reprinted from Anatomy and Physiology 6e, Thibodeau & Patton (2007) with permission from Elsevier.

Figure 10.3 • • Seyle's hypothesis about activation of the stress mechanism.

Reprinted from Anatomy and Physiology 6e, Thibodeau & Patton (2007) with permission from Elsevier.

In Chapter 3 the concept of a stressor was briefly examined in relation to various types of touch and other stimulation via the sense organs. A stressor acts to arouse the sympathetic branch of the ANS; massage is frequently used to achieve the opposite effect, the aim being to provoke a decrease of activity in the sympathetic branch and an increase of activity in the parasympathetic branch of the ANS, thus returning the body to a normal balance.

Arousal is the result of an individual's personal response to any stimulus perceived as a threat. Clinical stress may occur if the arousal persists and the individual develops feelings of being unable to cope; thus, stress can be viewed as a form of chronic arousal. Prolonged stress may result in raised levels of cortisol, which can have further harmful effects, such as decreased immunity and hypertension. Unremitting stress is undesirable for the human organism. To maintain health there must be a reversal of the arousal and a return to a normal baseline state of homoeostasis (Table 10.1).

Table 10.1 Stress-related diseases and conditions

| Target organ or system | Disease or condition |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular system | Coronary artery disease |

| Hypertension | |

| Stroke | |

| Disturbances of heart rhythm | |

| Muscles | Tension headaches |

| Muscle contraction backache | |

| Connective tissues | Rheumatoid arthritis (autoimmune disease) |

| Related inflammatory diseases of connective tissue | |

| Pulmonary system | Asthma (hypersensitivity reaction) |

| Hay fever (hypersensitivity reaction) | |

| Immune system | Immunosuppression or immune deficiency |

| Autoimmune diseases | |

| Gastrointestinal system | Ulcer |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | |

| Diarrhoea | |

| Nausea and vomitting | |

| Ulcerative colitis | |

| Genitourinary system | Diuresis |

| Impotence (erectile dysfunction) | |

| Frigidity | |

| Skin | Eczema |

| Neurodermatitis | |

| Acne | |

| Endocrine system | Diabetes mellitus |

| Amenorrhea | |

| Central nervous system | Fatigue and lethargy |

| Type A behaviour | |

| Overeating | |

| Depression | |

| Insomnia |

From Anatomy and Physiology 6e, Thibodeau & Patton (2007), Elsevier.

Some people with clinical stress initially require pharmacological intervention, but longer term therapies focus principally on developing coping strategies which may be in the form of:

Therapists who work in mental health care find that massage is a useful component when teaching body awareness techniques; this is often the first stage of physical treatment which attempts to reverse the musculoskeletal aspects of stress, such as muscle tension. Massage is not used in isolation but as an integral part of the rehabilitation programme; it may enhance relaxation and also promote integration of the physical senses.

Outside the orthodox health care setting, people often seek massage for ‘stress’, which has become a common term used to describe feelings of fatigue, tension and general weariness brought on by, for example, overwork, lack of sleep and worry. This condition is clearly to be differentiated from clinical stress, but massage is an appropriate prophylaxis if used in conjunction with exercise and other activities which promote physical and mental well being.

Anxiety and depression

Feeling anxious or depressed is a normal response to harrowing life events such as bereavement, loss of a job or financial difficulties. In healthy people these feelings reduce as the person adapts to the situation, uses coping strategies and returns to a state of mental well being. Anxiety and depression become mental disorders when the feelings are prolonged and constant.

In anxiety states people may experience irrational fears concerning everyday activities or the carrying out of normal routine tasks. They may exhibit physical symptoms consistent with increased sympathetic nervous system activity, such as muscle tension, palpitations, sweating and insomnia. Training in relaxation should be a component of anxiety management for these patients, and for many individuals massage will be a valuable prelude to this. Most patients with anxiety states have forgotten how it feels to be physically relaxed and massage is valuable in preparing these people for subsequent self-relaxation techniques.

A depressed patient will express profound sadness and social withdrawal; other symptoms may include impaired concentration, loss of interest in life, emotional lability, eating disorders, fatigue, irritability, insomnia, early morning waking and suicidal thoughts. Treatment is often long term and complex. Antidepressant medication is commonly prescribed together with occupational, physical and psychotherapy. Initially a patient with depression may be more comfortable with a passive type of treatment. Some depressed patients will also have symptoms of anxiety and for these people a sedative massage is appropriate but, to reduce the risk of therapy dependence developing, the therapist may encourage the individual to learn self-massage or self-acupressure as a component of a relaxation strategy. Dependence is less likely to result if it is explained that any passive treatment administered by the therapist is a preliminary to the patient being taught how to massage him- or herself or to start active exercises. This explanation will also help to prevent any feelings of rejection when the massage treatment comes to an end.

Many patients with chronic stress, anxiety or depression will also exhibit dysfunctional posture and movement patterns. This reflects the effect of the psyche on physical function and exemplifies non-verbal communication of the emotions of an individual. These dysfunctions signal the need for body awareness training, the object of which is to create the conditions necessary for a patient to begin to integrate sensory information, thus becoming more aware of posture and movement. For these patients massage may be the chosen treatment to help reduce muscle tone and to facilitate physical activities. It may also be of benefit by prompting the patient to connect with pleasant physical sensations, thereby promoting a positive body image and, ultimately, helping to restore self-esteem.

Massage may be the only regular experience of caring touch for a large proportion of the population. Sedative massage is used frequently as a treatment by therapists, particularly nurses, for those who are tactually deprived. This client group is largely found among elderly people being cared for within institutions, the terminally ill and the chronically sick. The importance of massage to these groups is that, in its absence, they may experience not only tactual deprivation but also sensory deprivation, as the opportunities for normal sensory input are not currently a feature of many hospitals and other residential care environments. The massage session also provides an opportunity to establish an effective therapeutic relationship by enhancing the rapport between patient and therapist.

Group therapy

This approach to treatment works well with groups of clients who are survivors of abuse, provided an experienced therapist supervises and counselling is available should the need arise. Mutual support groups for carers may also benefit from learning how to give relaxation massage to each other; carers are often tense and so benefit from relaxation techniques and caring touch.

Massage can be used as a means of promoting trust and cohesion within the group. Hand or foot massage should be demonstrated by the therapist and, under her supervision, massage can be given and received by group members. Even individuals who initially are tactually defensive may be drawn into this activity when they recognise the benefit that other members derive from the massage. Members of such a group tend to become enthusiastic learners. Inevitably the activity leads to questions from individuals about the benefit of massage, which presents an opportunity for the therapist to discuss topics of health education.

Other uses of relaxation massage

A further area for the use of sedative massage is as a prophylaxis against musculoskeletal dysfunction secondary to occupational stresses. Many workers sit, stand or move in ways that engender pathologically increased tone in some muscle groups. A classic example is the computer operator who frequently has increased tone in the upper back and neck muscles, as a result of prolonged static contraction of these muscle groups. The condition may go undetected until the therapist begins to massage the involved muscles, which are often painful. Once an employee is alerted to the potential problems he/she should be advised on how to work with ergonomic efficiency, to take regular breaks and to maintain good posture. Intervention at an early stage may help to avoid chronic muscle tension, muscle imbalance, adverse neural tension and postural dysfunction.

Although we have discussed in this section specific groups of people who are likely to benefit from massage as a relaxation therapy, there is no intention to suggest that the therapy should be confined to those with specific medical disorders. A large section of society chooses to have massage for the pleasurable experience and the positive psychological feelings of health it can give. Many people are now taking responsibility in promoting their own health and engaging in illness prevention. They are turning to various complementary therapies which they believe give them some control over their own health care. A growing fitness and leisure industry promotes activities that encourage an increasing number of people to become actively involved in maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Receiving regular massage is often a part of that endeavour.

The research

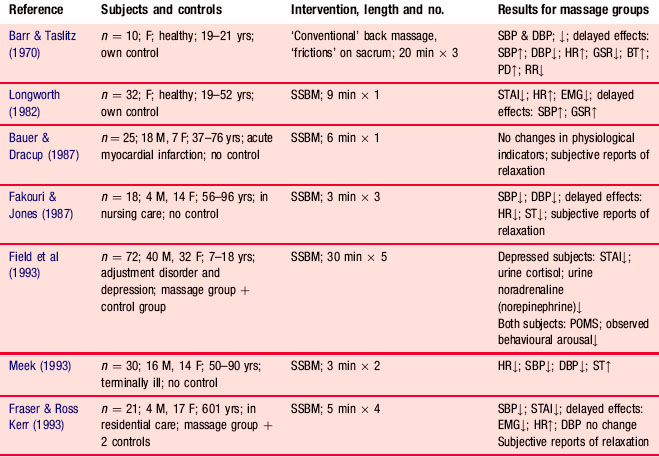

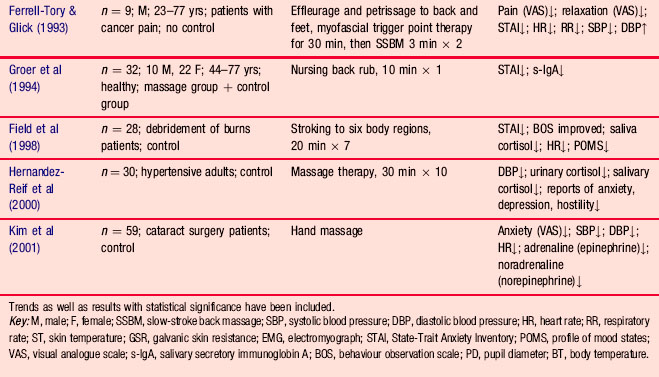

Several studies have explored the link between massage, autonomic effects and/or perceived levels of anxiety (Table 10.2). While some of the studies have shown significant changes of indices of autonomic activity, self-reported anxiety, or both, others present conflicting results, making interpretation of the studies as a whole difficult. Many of the studies have methodological and statistical limitations, and demonstrate potential internal bias. There are differences in sample sizes, populations, types of massage employed, time scales and number of massages. Some are pilot studies carried out to ascertain the relevance of massage to a particular profession working with a certain client group, and as such the results cannot be generalised. Despite these deficiencies it is possible to draw some inferences from the studies viewed as a whole. It is clear, for example, that studies which used a population who were residing in potentially stressful circumstances or with disease states (as opposed to a normal population) show results that appear to be more consistent, even when a widely different methodology was employed.

Table 10.2 Table of studies which have examined the link between massage and ANS sympathetic activity and anxiety

Two of the studies, those of Fakouri and Jones (1987) and Meek (1993), show consistent results, suggesting a decrease in autonomic arousal. However, the one measurement that shows consistent results across the studies in which it was employed is that of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, suggesting that this is a more predictable indicator of anxiety than the more traditionally used physiological measurements of autonomic arousal. The importance of the studies, taken as a whole, is that there appears to be no clear link between autonomic arousal and self-reported anxiety. The assumption that there is a correlation between autonomic arousal and perceived anxiety needs to be reappraised since, in the light of these studies, the link appears to be tenuous.

The results suggest that the hypotheses of future studies of this genre would be better tested by the employment of psychological measurements. A paradigm shift may be necessary to ensure that what is being tested is clinical effectiveness, which is defined as ‘the scientifically proven usefulness of a treatment in alleviating symptoms or combating disease’ (Ernst & Fialka 1994). Research in this area has traditionally focused on physiological effects, rather than clinical effectiveness. As it is widely accepted, in the present context, that massage is used as a coping mechanism and not a cure, physiological measures will not translate as showing clinical effectiveness. Weze et al (2007) demonstrated statistically significant improvement in self-reported stress, anxiety and depression following four 1-hour sessions of static touch. It is evident that further randomised longitudinal field studies capable of measuring self-reported anxiety and any consequent changes in behaviour and function are needed.

Forms of sedative massage

A full body massage will usually take from 45 to 90 minutes, depending on the time available, the variety of strokes used and regions of the body that may require extra attention. When increased muscular tone is found, the therapist may spend more time working in this region until a decrease in tone is achieved. Alternatively, it can occasionally be advantageous to continue with the full body massage and then return to troublesome areas, which may then be found to have reduced in tone. It is unlikely that very ill patients would tolerate a full body massage. With the very ill it is advisable to concentrate on one area, such as the back, the neck and shoulders, or the face. In addition, many therapists working in a health care environment are so constrained by time that a full body massage is not possible. It is suggested that a 3-minute slow-stroke back massage may prove effective in these circumstances (Fakouri & Jones 1987, Labyak & Metzger 1997, Meek 1993). If possible, the patient should lie prone. The therapist, using both hands, should use reciprocal strokes bilaterally over the posterior rami from the occiput to the sacrum in slow and rhythmical movements.

The starting point for the full body massage can be variable and is best decided upon by the preferences of the client and therapist. At the first massage the client may prefer to start in the prone position with the therapist beginning work on the back; for anyone who is anxious or ill at ease, this is the least threatening position.

When giving a relaxation massage the strokes should be light but firm, care being taken not to be so light as to stimulate rather than sedate. The therapist must be calm and avoid giving the impression that she is in a hurry—if the therapist is not feeling relaxed, then neither will the patient. Appropriate music may be played if the patient finds it soothing.

The lubricant may be applied by superficial stroking of the body region to be massaged; for a sedative massage it is acceptable to use slightly more than the normal quantity of oil as traction of the skin is unnecessary and undesirable. Essential oils may be used for their therapeutic properties and to enhance the pleasurable qualities of the massage (see Chapter 7).

Box 10.1 presents a suggested sequence for a full body sedative massage in the absence of complicating factors. The depth of pressure should be light to moderate and the strokes should be made slowly and rhythmically.

Box 10.1 Full body sedative massage

Sequence of massage and manipulations

Begin all the regions by stroking:

• The back: effleurage, light palmar and finger kneading, effleurage, transverse stroking, effleurage.

• The back of the legs: effleurage, light kneading, effleurage.

The patient turns to supine, pillows under the head and knees:

• The front of the legs: effleurage, light kneading, effleurage.

• The arms: effleurage, light kneading, effleurage.

• The abdomen: effleurage, transverse stroking, effleurage.

• The chest, shoulders and neck: effleurage, light finger kneading, effleurage.

• The face: effleurage, light finger kneading, plucking, effleurage.

Barr J.S., Taslitz N. The influence of back massage on autonomic functions. Phys. Ther.. 1970;50(12):1679-1691.

Bauer W.C., Dracup K.A. Physiological effects of back massage in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Focus Crit. Care. 1987;14(6):42-46.

Ernst E., Fialka V. The clinical effectiveness of massage therapy: a critical review. Forsch. Komplementarmed.. 1994;1(5):226-232.

Fakouri C., Jones P. Relaxation treatment: slow stroke back rub. J. Gerontol. Nurs.. 1987;13(2):32-35.

Ferrell-Tory A.T., Glick O.J. The use of therapeutic massage as a nursing intervention to modify anxiety and the perception of cancer pain. Cancer Nurs.. 1993;16(2):93-101.

Field T., Morrow C., Valdeon C., et al. Massage reduces anxiety in child and adolescent psychiatric patients. International Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 1993:125-131. (July)

Field T., Peck M., Krugman S., et al. Burn injuries benefit from massage therapy. J. Burn Care Rehabil.. 1998;19(3):241-244.

Fraser J., Kerr J.R. Psychophysiological effects of back massage on elderly institutionalized patients. J. Adv. Nurs.. 1993;18:238-245.

Groer M., Mozingo J., Droppleman P. Measures of salivary secretory immunoglobin A and state anxiety after a nursing back rub. Appl. Nurs. Res.. 1994;7(1):2-6.

Guyton A.C., Hall J.E. Textbook of medical physiology, eleventh ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2006.

Hernandez-Reif M., Field T., Krasnegor J., et al. High blood pressure and associated symptoms were reduced by massage therapy. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther.. 2000;4(1):31-38.

Kim M.S., Cho K.S., Woo H., Kim J.H. Effects of hand massage on anxiety in cataract surgery using local anesthesia. J. Cataract Refract. Surg.. 2001;27(6):884-890.

Labyak S.E., Metzger B.L. The effects of effleurage backrub on the physiological components of relaxation: a meta-analysis. Nurs. Res.. 1997;46(1):59-62.

Longworth J.C.D. Psychophysiological effects of slow stroke back massage in normo-tensive females. ANS Adv. Nurs. Sci.. 1982;6:44-61.

Meek S.S. Effects of slow stroke back massage on relaxation in hospice clients. J. Nurs. Scholarsh.. 1993;25(1):17-21.

Seyle H. History and present status of the stress concept. In: Goldberger L., Breznitz S., editors. Handbook of stress: theoretical and clinical aspects. New York: Macmillan, 1982.

Thibodeau G.A., Patton K.T. Anatomy and physiology, sixth ed. St Louis: Mosby Elsevier, 2007.

Weze C., Leathard H.L., Grange J., et al. Healing by gentle touch ameliorates stress and other symptoms in people suffering with mental health disorders or psychological stress. Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2007;4(1):115-123.