7 Massage techniques

The first section of this chapter contains information about the lubricants and essential oils that may be used in massage. Stance, posture, movement and safety issues, in relation to both the therapist and the patient, are also addressed. The second section describes the techniques and manipulations of classical massage, and also includes those of neuromuscular technique and deep transverse frictions.

Lubricants (massage media)

Massage may be performed either with or without a lubricant; both methods have ardent supporters who are prepared to dispute the merits of the opposing point of view. To enable the therapist to form her own opinion on this question, some of the most common points for and against are presented here.

Points for massage with a lubricant

• Friction on the skin is reduced;

• Fragile skin is protected from being stretched;

• Very hairy skin is protected from being pulled;

• Some oils (e.g. wheatgerm, olive) are said to aid skin nutrition;

• Perspiration can be absorbed by a powder lubricant;

• The gliding effect of some massage manipulations is enhanced;

• Perfumed oil has a beneficial psychological effect on the patient;

• Essential oils can be selected for their therapeutic properties; and

• Lubricants make it easier to perform a comfortable massage.

Points for massage without a lubricant

• Massage can be applied more deeply in the tissues;

• Oil is messy to use and easily spilled;

• A lubricant may cause an allergic reaction;

• Lubricants create an increased risk of infection;

• The tissues are more easily palpated;

• The massage can be more stimulating;

• Tissues are more easily manipulated if they are not slippery;

• Commercial massage oils are over-priced and highly scented; and

A balanced approach to these opposing viewpoints is recommended. Clearly there are occasions when a lubricant is desirable and times when it is not. The following factors may be taken into account when deciding whether the use of a lubricant is appropriate to a specific treatment:

Condition of the skin

On hairy, fragile or scaly skin a lubricant will aid patient comfort and prevent irritation.

Possibility of allergic reactions

Some people are allergic to nuts and will have an anaphylactic reaction (which causes shock, an acute fall in blood pressure, laryngeal oedema and bronchospasm, and can be fatal) if they are exposed to oil derived from nuts. Peanuts are the most common allergen: about 1 in 500 of the population is affected (Demain 1996). This type of allergy is becoming more common and exists whereby very young children are sensitised (Ewan 1996). Arachis oil is derived from peanuts and many commercial massage lotions use a nut oil, such as almond or hazel, in their preparation. The therapist should always question the patient concerning allergies before using any lubricant and be fully aware of the constituents of any lubricant she has not prepared herself.

Safety

Talc can be inhaled into the lungs where it can cause irritation. It can also cause eye irritation. It is no longer in use in the UK National Health Service for this reason.

Necessity for skin traction

Massage manipulations that grasp and lift the superficial tissues are ineffective if too much lubricant is used, making the surface of the skin slippery, and a highly viscous oil can cause excess skin traction. A small amount of oil or powder can, however, make these techniques more comfortable for the patient and prevent friction. It is not appropriate to use a lubricant for massage manipulations where the therapist's hand does not glide on the skin, but specifically moves the skin on underlying tissue. For these manipulations it is important for there to be traction between the massaging hand and the patient's skin; a lubricant would not serve any purpose.

Categories of lubricant

The literature contains many examples of lubricants that have been used in massage, some of which have waned in popularity in recent years.

Lubricants of vegetable origin

Oils: corn, safflower, sesame, soyabean, sunflower, wheatgerm, coconut, almond, hazel, grapeseed, arachis (peanut), olive, avocado. Powder: corn starch.

Lubricants of mineral origin

Baby oil, petroleum jelly, liquid paraffin, French chalk, talc, cold cream.

Lubricants of animal origin

Historically, various animal-based media has been used including wool fat, lanolin, soap solution, neat's-foot oil (neat is an old Saxon word meaning animals of the ox kind), hog's lard.

Other categories

This includes commercial preparations of oils, creams and lotions. Many of these use petrochemicals as a base; some use vegetable oil; and some are water based and easily removed from clothing by washing. Many commercial products do not list the ingredients and it is therefore impossible to determine whether they are suitable for use on a patient with specific allergies.

Comments

It is advisable for the therapist to sample a variety of the available lubricants and to try using them on her own skin. This will enable the therapist to judge their suitability for massage and experience the type of sensation that a patient may feel when they are used. (N.B. The authors do not recommend the use of hog's lard.)

Oils of vegetable origin are generally the most pleasant to use and are suitable as a carrier with essential oils. It has been found to penetrate transcutaneously in neonates (Solanki 2005), whereas the molecular structure suggests that it is unlikely to penetrate this deeply in adults (Zatz 1993). Mineral oil does not penetrate the skin well and is therefore unsuitable for carrying volatile oils into the tissues. The lack of this property does, however, convey an advantage for general massage purposes, as it tends to stay on the surface of the skin and less is needed. There is some controversy concerning the use of mineral oil. Taken internally in large quantities it can interfere with the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins, but there is no evidence to suggest that it is detrimental when used as a massage lubricant (Skiba 1993). Some vegetable oils are more viscous than others (e.g. olive, wheatgerm) and should be added in small quantities to a lighter oil. Vegetable oils can become rancid; keeping supplies refrigerated in a well-sealed container slows this process, as does the addition of 5% wheatgerm oil, which has antioxidant properties. A therapist with sweaty palms may find that powder is a more suitable lubricant as it absorbs some of the moisture. A fine non-perfumed talc has traditionally been a useful addition to the therapist's equipment; some patients prefer it to oil and it does not degrade. Consent should be obtained from the client before using talc and great care should be taken to ensure it does not invade the atmosphere and that it cannot be inhaled by either the client or the therapist.

Essential oils

The medium used in massage can be therapeutic in its own right. Although oils can be used solely as lubricants for massage, they can also be the vehicle for the absorption of a particular substance, selected for its own therapeutic properties, into the body. Liniments, for example, have long been rubbed into the skin to affect the underlying tissues.

Aromatherapy is the name given to application of essential oils, which are the oils that provide the scent and/or flavour to flowers, fruit and herbs. They have been extracted from the plants and used for this purpose for thousands of years (Tisserand 1994), as herbal medicines, inhalations or compresses. Pure oils can be extracted from the leaves, flowers or seeds of plants and used for specific therapeutic purposes. Many have a pleasant smell which produces a psychological effect, a feeling of well being. Inhalation also ensures that they enter the bloodstream quickly through the highly vascular lung and respiratory tract fields; a popular method of inhalation entails heating the oils in an aromatherapy burner. Alternatively, they may be added to a warm bath for inhalation and skin absorption. They can therefore be self-administered, used simply to create a pleasant smell and atmosphere in a room, or can be skilfully prescribed and blended by an aromatherapist. Detailed discussion of each oil, sufficient to guide professional aromatherapy prescription, is beyond the scope of this book. However, the principles are described here to a sufficient depth to assist massage therapists to select a limited number of oils for safe use as a therapeutic or pleasantly scented medium.

Massage is a particularly popular way of applying essential oils, and results in a slow penetration. The oils are dissolved in a carrier oil and used as the medium for massage, allowing the effects of the oils to combine with the therapeutic effects of the massage. Relaxation massage should be used (see, for example, the one described in Chapter 10). As with any therapeutic substance that enters the body, dangers and side effects may be present and anyone using these oils for any purpose should be aware of them. This applies particularly to a therapist using oils in health care settings where clients may have a variety of health problems. Unfortunately, research into the effects of the oils is patchy and knowledge is based predominantly on oral tradition. Where research has been undertaken, it has often focused on the main chemical constituents of the oils, so pure oils should be used in which the constituents are known. Good quality oils from professional suppliers are the purest, and inexpensive ones should be avoided. Air, heat and light can cause degradation of oils. This results in a changed chemical composition which may be less effective or more toxic; therefore oils should be kept in a cool, dark environment and not kept for longer than 6 months once opened unless in a fridge. This safety advice is important as degradation and oxidation may make the oils more likely to become carcinogenic, although the transfer of research conducted on rats to humans is not straightforward (Tisserand 1996).

Any therapy which has been used throughout history becomes refined through experience and often the knowledge surrounding its use is accurate. Present-day researchers are attempting to deepen this knowledge of essential oils in the light of current scientific methods by isolating specific constituents of the oils and testing their effects. Albert-Puleo (1979) reviewed the literature concerning the oestrogenic properties of fennel and anise, as identified by numerous animal experiments conducted in the 1930s and 1940s. He suggested that the oestrogenic active ingredients are anethole polymers. Work by Taylor (1964) has shown fennel to have low toxicity and no demonstrable carcinogenicity. Thyme (Thymus capitatus) has been found to have strong fungitoxic properties (Arras & Usai 2001).

Other researchers have attempted to define the effects of individual oils and isolate their mechanism of action. An example is the work by Aqel (1991) in which he applied oil of rosemary to rabbit and guinea-pig tracheal muscle samples. The oil inhibited muscular contractions induced by histamine and acetylcholine. Aqel suggested that the oil is a calcium modulator. Hills and Aaranson (1991) agreed with this suggestion, following similar work on the effects of peppermint oil on smooth muscle. Oil of orange diffused through a dental waiting room was found to have a relaxant effect (Lehrner et al 2000). Cooke and Ernst (2000) conducted a systematic review and concluded that aromatherapy massage has a mild, transient anxiolytic effect, useful for relaxation but not strong enough for the treatment of anxiety. Anderson et al (2000) found that tactile contact between mother and child in the form of massage improved childhood ectopic eczema but that adding essential oils was not more beneficial. A number of studies into the clinical effects of lavender oil in, amongst others, depression (Akhondzadeh et al 2003), postpartum perineal discomfort (Dale & Cornwell 1994), during radiotherapy (Graham et al 2003), anxiety and self-esteem (Rho et al 2006) and dementia (Snow et al 2004) have been conducted. The evidence remains unclear in all except for anxiety. Tea tree oil has attracted research interest as laboratory studies have found antimicrobial properties (Christoph et al 2000). Human studies, mostly on fungal infections, remain inconclusive (Arweiler et al 2000, Martin & Ernst 2004, Satchell et al 2002).

There is concern about the possibility of adverse effects of oils. Research in this area has often been conducted on animals using huge dosages of the oil, so transferability of findings to humans is difficult. Elliot (1993) reported a case of tea-tree oil poisoning, but suggested it may have been an allergic reaction. There is a growing body of literature on this topic (such as Prashar et al 2004) and this should be studied in detail by anyone qualified to prescribe essential oils for massage. This is also the case for interactions of essential oils with drugs. This does, however, highlight the fact that ingestion of these oils can carry some risk, the extent of which is unknown where there has been insufficient research. Studies into microbiological effects are easiest to conduct under controlled, scientifically valid conditions. Bassett et al (1990) found tea-tree oil to be as effective as 5% benzoyl peroxide in the treatment of acne, with fewer side effects. Carson and Riley (1994) found that terpinen-4-ol was the main antimicrobial component of tea-tree oil. It was tested against 12 organisms, including Staphylococcus aureus, Candida albicans and Lactobacillus acidophilus, and only one of the 12 (Pseudomonas aeruginosa) was found to be resistant to the oil. A detailed literature review of essential oils will not be undertaken here, but the clinically based studies are often inconclusive, conducted on animals and not readily transferable to humans. Caution is therefore needed and external application is safer than internal use. Aromatherapists should understand as much as possible about the oils they prescribe, and attempts are being made to examine and address safety issues (Tisserand & Balacs 1995).

Use of essential oils in massage

Choice and prescription of oils can be interesting. The principles of perfumery and medicine are used: asking what types of scents the patient prefers and blending from a base note (fixative), middle note (relates to bodily functions, with a longer lasting scent) and top note (volatile and stimulatory, often smelled immediately the top is removed from a bottle). It is possible to buy an essential oil preparation or a massage oil containing an essential oil. The massage therapist should ensure that contraindications for any oil are understood if these are to be used. Blending of essential oils must not be carried out by anyone not qualified to make such a preparation and local rules/laws on such manufacture should be followed. Medical history and present complaints are examined in detail to identify any contraindications or potential sensitivities to a particular oil (for example: Are migraine attacks provoked by strong odours? Is the individual epileptic?) and to use the blend to specific effect. The exact amount of carrier oil required varies with the absorptive properties of individual skin, but blending 3–12 drops of essential oil in 30 ml carrier oil is a useful guide. To ensure a pleasant blend, essential oil should be added to the carrier drop by drop, using as little as is required. Blending should only be undertaken by those qualified in aromatherapy. It should be noted that drop size differs between manufacturers and therefore dosage is approximate. The therapist cannot be sure of the exact dose administered (Olleveant et al 1999).

The massage is usually a full body massage as this ensures that a good dosage is absorbed into the bloodstream. The oils are volatile and evaporate readily, so more is blended than is actually absorbed into the skin. None the less, a full body massage administers a good dose and should therefore not be given more than once per week. The therapist should be aware of the potential dose she is receiving herself: four massages are regarded as maximal in any one day. Both therapist and client should drink plenty of water after massage as the oils have a diuretic effect and can lead to dehydration and headaches: they can often be tasted after a massage, so encouraging clients to drink is not difficult.

Contraindications

There are few specific recorded contraindications to general aromatherapy, although individual oils have their own specific contraindications and cautions. Obviously, the contraindications for massage should be respected and allergic reactions guarded against. On no account should essential oils come into contact with the eyes. If they do, the eyes should be douched with water and medical help sought. Tea-tree oil should not be used in childbirth as it has been found to reduce uterine contractions in rats (Lis-Balchin et al 2000).

Users of aromatherapy should be aware of a t study reported in the journal Food and Chemical Toxicology which examined the toxic effects of dill, peppermint and pine (Lazutka et al 2001). To summarise: all three oils were found to cause cytotoxic genetic mutations on human lymphocytes. These are worrying findings which raise concerns across all essential oil use. Until more is known about safe doses in humans, it would be wise not to use dill, pine or peppermint oils in massage.

Precautions

Precautions for each oil should be understood. In general (in relation to massage), certain oils should not be used in pregnancy as they have been found to cross the placental barrier in high doses. Oils that contain bergapten (bergamot) can produce ultraviolet sensitisation and phototoxic reactions have been reported (Kaddu et al 2001), so care should be taken, particularly in summer. Oils can cause contact dermatitis. Increased use of lavender flowers around the home and in pillows has been found to cause contact dermatitis (Sugiura et al 2000). Lavender, jasmine, rosewood, laurel, eucalyptus and pomerance have been reported to cause skin reactions (Schaller & Korting 1995). Severe contact dermatitis reactions to tea-tree oil have also been reported (Khanna et al 2000) as has hypersensitivity (Mozelsio et al 2003). Great care should be taken to ensure that susceptibility to adverse reactions is assessed prior to massage. It should also be noted that chemical constituents often behave differently when combined together, so the therapist should be aware that research on individual oils will not provide a total picture. Damaged skin is best avoided except when the practitioner is highly experienced; oils that may provoke sensitivity should not be used on babies and young children.

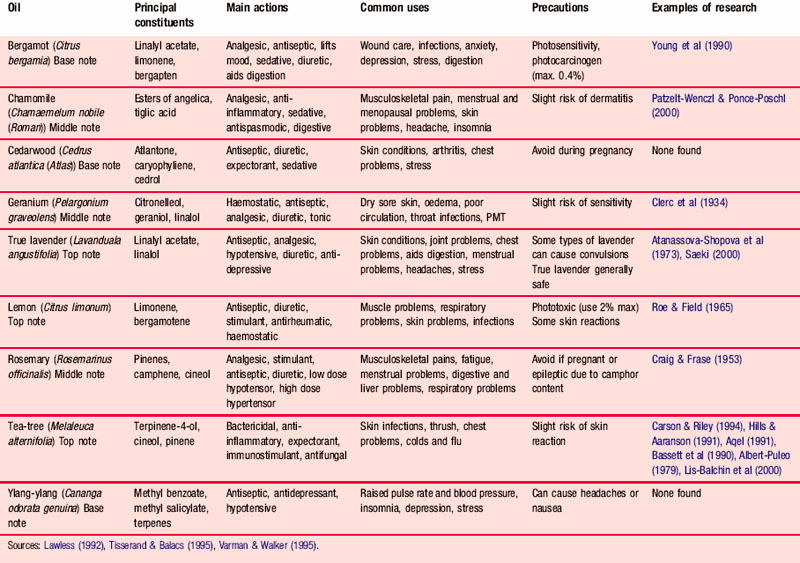

Table 7.1 lists the oils in common use, together with their constituents, main actions and uses. It also summarises the precautions for each oil.

Applying the lubricant

• The lubricant should be at skin temperature. Oil in a sealed container can be warmed by standing it in hot water. Talc can be warmed by being left close to a heat source.

• Avoid spillages. Oil can be transferred into a small squeeze bottle; this is probably the safest method. Alternatively it can be put into a shallow dish and placed on a surface close to the treatment couch but where it is not likely to be upset.

• The therapist's hands should be washed before beginning the massage.

• The patient's clothing should be protected.

• Application. The lubricant, be it oil or talc, is first rubbed onto the therapist's hands and then transferred to the skin of the patient. This method safeguards against applying too much lubricant or spilling it on the patient's clothing; it also protects the patient from the unpleasant sensation of feeling a sudden dollop of oil.

• The lubricant is spread on the skin by stroking or effleurage.

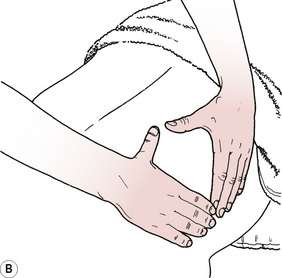

• Reapplication. During the massage treatment it may be necessary to reapply the lubricant and sometimes it is desirable not to lose physical contact with the patient. The technique is achieved by keeping the dorsum of one hand in contact with the patient so that the palm is upwards and can receive the lubricant from the other hand. The hands are rubbed together, maintaining patient contact, and the lubricant is then reapplied to the skin in the usual way. To achieve this method gracefully the lubricant should be within easy reach of the treatment couch.

• Hygiene. To ensure there is no risk of cross-infection, at the end of treatment the therapist should dispose of any oil that may have become contaminated and thoroughly wash her hands.

Stance, posture and movement

Therapists who perform massage regularly are aware that the activity places demands upon their physical capacities. Unless stance, posture and movement are addressed initially by the student therapist she will find that giving massage treatments is fatiguing. Just as in any repetitive physical activity, the therapy also has the potential to induce overuse syndrome. To achieve maximum effectiveness the therapist should comply with ergonomic principles. This means giving attention to the safety of her stance and posture and to the economy of her movements. Although this may seem complicated when first learning how to massage, the student therapist should not feel disheartened. As with any other psychomotor skill, the refinements of the technique are achieved with practice; expect less than perfect coordination when you first begin.

Base of support

The position of the feet is important for three reasons. First, correct foot positioning enables the therapist to reach all parts of the patient's body without strain. The joints of the hands, arms and spine can be held in a stress-free position if body-weight is transferred from one foot to the other, thus reducing the need to reach.

Second, the direction in which the feet face is important to enable weight transference without trunk rotation. The knee to which the weight is transferred flexes, resulting in a lunge posture.

Third, foot position is important for balance. The body relies on the feet for its base of support—the area that encloses the feet and includes the space between them. The further apart the feet are, the wider the base of support. The weight of the body is transferred to the ground through the line of gravity; the body is most stable when the line of gravity falls in the centre of the base. If the line of gravity falls outside the base, the body will not be able to balance; this displacement is unlikely to occur when the base of support is large. Stability and balance enable the body to remain relaxed and free the muscles to perform the massage without strain on the therapist.

Stance

The therapist faces the direction of the massage manipulations. This varies according to the area of the body to be treated. The following examples can be adapted to encompass other massage techniques.

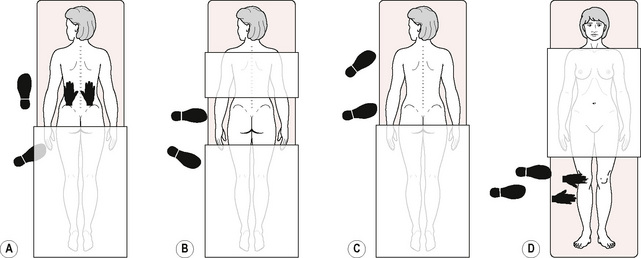

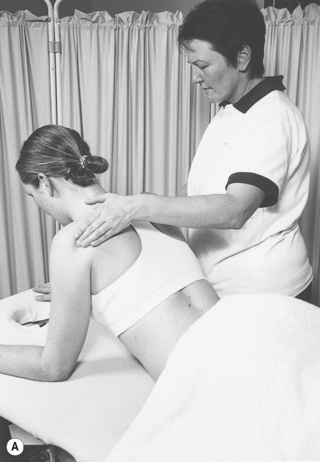

Long manipulations

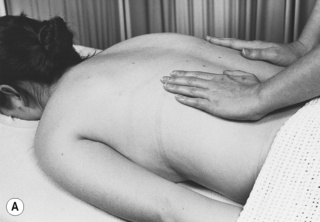

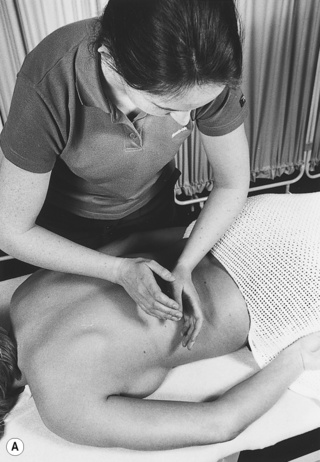

For effleurage to the back, for example (Fig. 7.1A), the therapist stands close to the left of the treatment couch where she can place her hands at the start of the stroke with no trunk rotation. The left foot is a comfortable stride forward of the right one; the left foot points towards the head of the treatment couch and the right foot is angled. At the start of the stroke there is more weight on the right foot than on the left; the therapist is using some body-weight to create the pressure of the stroke. As the stroke progresses up the back, weight is transferred from the right foot to the left; the left knee flexes so that a lunge position is adopted.

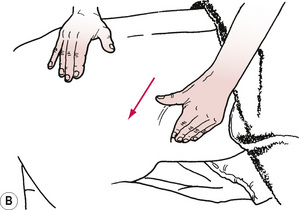

Transverse manipulations

For wringing the back, for example (Fig. 7.1B), the therapist stands close to the treatment couch facing across the patient's back. The left foot is on a level with the thoracolumbar junction, which is where the manipulation begins. The right foot is angled so that the right lumbar segment can be treated with no trunk rotation. As the strokes move towards the buttocks, the therapist transfers weight to her right leg and flexes the knee. To massage the right thoracic region, the therapist adjusts her foot position so that the right foot is now on a level with the thoracolumbar junction. The procedure is repeated.

Small-range manipulations on a specific structure

For frictions, for example (Fig. 7.1C), the therapist faces the structure to be treated; the left foot is forwards of the right. The left hand is supporting the patient's thigh while the right hand performs the manipulation. There is more weight being taken through the right foot than the left and, as this is a deep manipulation, there is substantial weight transference to the patient through the therapist's arms to exert pressure on the tissues.

Posture and movement

The therapist should apply the same general principles of safe posture when giving massage as she would with any task that has an element of risk to the musculoskeletal system. The major areas of risk are identified below and suggestions are made about prevention:

• Excessive reaching causes unsafe trunk movements and is linked with muscle fatigue and soft tissue injury.

Prevention: The therapist should stand close to the treatment couch. The correct stance will ensure that she is able to reach all parts of the area to be treated. When a small therapist is treating a very tall patient, it may be helpful to divide the treatment area into sections so that the therapist can change position between segments.

• Prolonged elevation of the arms necessitates static loading of the shoulder girdle muscles and is fatiguing, causing soft tissue damage and compromise to peripheral nerves.

Prevention: Ensure the height of the work surface is correct. This should be just below waist level so that it is rarely necessary to flex the shoulders beyond a 45° angle from the therapist's body.

• Excessive compressive forces can cause joint injury. The wrist and joints of the fingers and thumbs are those at greatest risk when massaging.

Prevention: Avoid prolonged repetition of movements and hyperextension of these joints. When performing manipulations that require compressive forces, keep the joints in a near-neutral position.

• Prolonged muscular activity of the arms and hands causes muscle fatigue.

Prevention: Avoid using muscles to create pressure. This is best achieved by transferring body-weight to the patient through the massaging hands. The therapist's shoulder, arm and hand should be free of tension. All movements should be kept to the minimum necessary to achieve the desired effect.

• Poor balance leads to faulty movement.

Prevention: Adopt the correct stance. A wide base of support lowers the centre of gravity and so aids equilibrium. Dynamic balance is achieved by a transfer of weight, at the correct time, from one foot to the other.

Environment and safety

The safety and comfort of the patient are paramount and it is the therapist's responsibility to ensure that high standards are maintained.

The environment

This should be tidy with equipment moved away from the area so that there is nothing the patient or therapist could bump into or trip over. For sedative massage, noise should be kept to a minimum if possible and, if not, as in a busy hospital department, it may be helpful to play music if the patient likes it. If music is played it should be relaxing and appropriate to the patient. It is always worth enquiring whether the chosen piece of music is acceptable to the patient, as associations triggered by particular music may produce unwanted effects that conflict with the aim of the massage.

The temperature of the environment should be comfortable for the patient. Steps should be taken to ensure that there is no interruption during the treatment session. Protecting the patient's privacy and dignity is essential.

All the equipment needed for the massage, such as lubricants, covers and pillows, should be placed near to the treatment couch. The couch should be prepared with fresh linen and be ready to receive the patient.

The therapist

If a uniform is not worn then the mode of dress is optional, provided it is appropriate to the task. Appropriate, in this context, means that the therapist should be professional in appearance and that her clothing should not constrain her movements. The therapist should remove any jewellery that could come into contact with the patient, for example long necklaces, watches, bracelets and rings. Long hair should be tied back. Fingernails should be trimmed so that they do not protrude beyond the fingertips. Before each treatment the therapist should wash her hands and ensure they are warm.

Infection control

The therapist who works in a hospital or clinic will find that there are existing infection control policies and she should strictly adhere to these. The following are the minimum standards that should be applied to protect against the transmission of infections or viruses borne by blood or body fluids:

• Practise high standards of basic hygiene, with regular hand-washing; the minimum frequency of hand-washing is between each client.

• Disposable plinth covers should be used and destroyed after each client.

• Treatment couches should be washed down regularly.

• Cover all skin wounds or lesions with a waterproof dressing.

• Protect the mucous membranes of the eyes, mouth and nose from blood or body fluids.

• Wearing rubber gloves, clear up blood, urine, vomit and faeces immediately; disinfect surfaces.

Patient positioning and draping

Adhere to the following principles:

• The patient must be comfortable and warm.

• The body part to be massaged should be free from clothing and jewellery.

• The body part to be massaged and the joints distal and proximal to it should be supported.

• Extra supplies of linen, pillows, blankets and towels should be nearby in case they are needed during the treatment.

The ideal patient position is lying on a treatment couch of adjustable height. For treatment to the arm and hand it is equally convenient to have the patient seated with the upper limb supported on a small table, with the therapist seated opposite. Massage to the neck and upper back can be performed with the patient sitting on a seated massage chair or seated at a table or on the couch. Pillows are piled up to a height that allows the patient to be supported anteriorly, with the upper limbs resting on the table. If the patient is not comfortable in any of these positions, the therapist should devise a suitable position which supports the body part to be treated and is also comfortable for the therapist.

Patient prone-lying on a treatment couch

• The couch should have a removable section for the face; if it does not, two pillows can be placed in an inverted ‘V’ shape so that there is a space for the patient to breathe.

• A folded sheet may be placed under the patient's chest. This can be wrapped around the back, or, when that area is being treated, it can be draped over the upper arms.

• A female patient who has large breasts may require a pillow under her chest.

• A pillow may be placed under the abdomen to reduce lumbar lordosis.

• A rolled towel or small pillow is placed under the ankles so that they are not in an extreme range of plantarflexion and the knees are slightly flexed.

• The patient is covered with a sheet; a blanket may also be required.

• The body part to be massaged is exposed by drawing back the cover from that area.

Patient side-lying on a treatment couch

• The patient may require one or two pillows under the head.

• The upper arm and upper leg are supported anteriorly by pillows.

• A heavily pregnant woman may require pillows to support her abdomen.

• The patient is covered with a sheet; a blanket may also be required.

• The body part to be massaged is exposed by drawing back the cover from that area.

Techniques and manipulations

This section of the chapter describes the techniques and manipulations of classical massage, together with neuromuscular technique and deep transverse frictions. Specialised techniques such as myofascial release, manual lymphatic drainage and acupressure are covered in Chapter 9.

Technique: stroking

Manipulation: long stroking

Procedure

The manipulation begins at the most proximal part of the area to be treated.

The therapist places the whole of her hands in contact with the skin (Figs. 7.2A, B).

A gentle but firm pressure is maintained.

The hands are drawn towards the therapist, leading the movement with the heel of the hand (Figs. 7.2C, D).

An even depth of pressure is maintained while the hands mould to the body contours.

The hands are lifted off smoothly at the distal region of the treatment area without trailing the fingers.

The following stroke overlaps the first, continuing until the whole of the body region is covered.

The manipulation may be adapted for small areas by the therapist using only one hand, the fingers or thumbs.

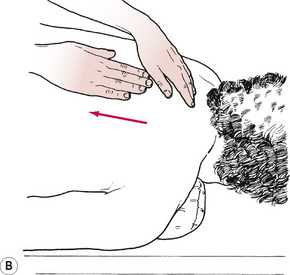

Manipulation: thousand hands

Procedure

The therapist places one hand in contact with the skin at the proximal part of the area to be treated.

The therapist strokes distally for about 15 cm.

The alternate hand begins an overlapping stroke, along the same line of treatment, before the first hand is lifted off (Fig. 7.3).

There is always one hand in contact with the skin.

The fingers should not trail on the skin when lifting off.

The strokes are continued to the distal part of the treatment area.

The manipulation is repeated on an adjacent area until the whole of the region has been covered.

Technique: effleurage

Features

The manipulation is commonly utilised at the start and end of a massage treatment and often between the various petrissage manipulations.

On fragile or hairy skin, oil or talc is applied liberally to avoid stretching the tissues or dragging the hair.

The manipulation is always performed towards the lymph glands.

Depending on the size and shape of the body region to be treated, the therapist may use one or both hands, fingers or thumbs.

Manipulation: effleurage

Procedure

The stroke begins at the distal part of the area to be treated.

The therapist contacts the skin and applies an even pressure to sink into the superficial tissues.

A sweeping movement is made to the proximal part of the treatment area, moulding to the body contours and maintaining the same depth of pressure throughout the stroke (Figs. 7.4A, B).

The stroke is rhythmic and slow to facilitate the movement of fluid.

The stroke is completed, over the site of lymph glands, with a slight pause and overpressure which is almost imperceptible to the patient.

The hands are lifted and repositioned at the start of the next stroke which overlaps the previous one.

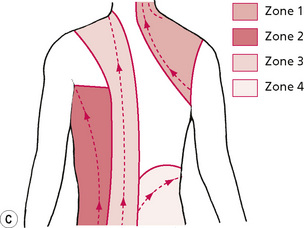

The strokes are continued until the whole of the body segment has been covered (Fig. 7.4C).

If there are no lymph glands in the body segment, effleurage is then continued to the site of the nearest lymph glands.

On cylindrical body segments, the hands or fingers are wrapped around the treatment area to perform the manipulation (Figs. 7.4D, E).

Technique: petrissage

Categories: kneading; wringing; rolling; picking up; shaking

Purpose

To aid venous and lymphatic return.

To aid removal of chemical irritants.

To increase mobility and length to fibrous tissue.

To restore mobility between tissue interfaces.

To aid interchange of tissue fluid.

To improve the appearance and mobility of subcutaneous tissue.

To increase extensibility and strength of connective tissue.

Features

Petrissage manipulations first compress the soft tissues; they are then lifted, squeezed or rolled, and taken to the tissue end-feel.

The manipulation is performed on superficial tissue, muscles or ligaments.

Petrissage manipulations should be avoided on sensitised tissue, where they may be painful.

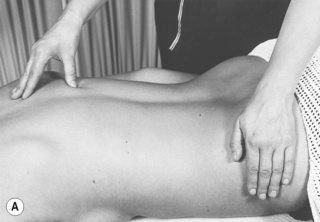

Manipulation: kneading

Procedure

The manipulation is performed with one or both hands (Figs. 7.5A, B), or the pads of fingers or thumbs, depending on the size and shape of the area to be treated.

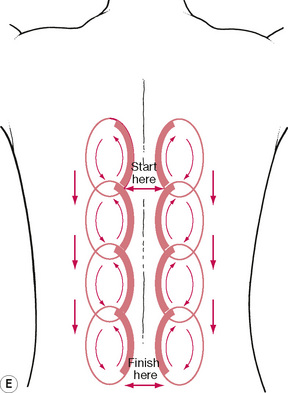

The stroke begins at the proximal part of the area to be treated and moves distally.

The therapist contacts the skin and compresses the tissues.

The skin is moved on the underlying tissues; there is no glide.

The hands or digits are moved in a circular motion, which causes skin wrinkling ahead of the movement and a slight stretch behind it.

When both hands are used to perform the stroke they are moved alternately: the right hand moves clockwise and the left hand in an anticlockwise direction.

Hands can be placed on opposite aspects of the limb to apply extra compression (‘box’ kneading).

There is a pressure phase when the tissues are compressed on to the deeper structures.

The position of hands for the pressure phase requires a slight adjustment for flat and cylindrical body segments (Figs. 7.5C, D).

After the first circular stroke a light glide is effected on the skin to reposition the massaging hand at the start of the next stroke.

The strokes are continued on adjacent areas, overlapping the previous stroke, until the whole of the treatment area has been covered (Fig. 7.5E).

When extra compression is required the manipulation is performed with one hand on top of the other to give reinforcement.

The therapist should take care to maintain finger and thumb joints in a near-neutral position when using the digits to perform the manipulation.

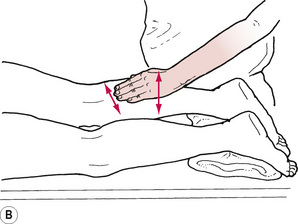

Manipulation: wringing

Procedure

Wringing may be performed on skin and superficial tissue using the pads of the fingers and thumbs (Figs. 7.6A, B).

Wringing may be performed on muscle using the whole of the hands (Figs. 7.6C, D).

The therapist places her hands on the skin with the fingers adducted and the thumbs abducted.

The fingers and thumbs are squeezed together so that a roll of tissue or muscle gathers between them.

The therapist pushes one hand away and draws the other hand towards her; the roll of tissue is twisted (Figs. 7.6E, F).

The twist is then applied in the opposite direction by changing the position of the hands.

The manipulation progresses along muscle in the direction of the fibres, beginning at one end and finishing at the other.

On superficial tissue the manipulation progresses forwards across the body region and then adjacently until the whole of the area has been covered.

Manipulation: rolling

Procedure

Rolling of small muscles and superficial tissue is performed with the pads of the fingers and thumbs.

Rolling of large muscles is performed with the whole of the hands.

The therapist places her hands on the skin with the fingers adducted and the thumbs abducted.

The index fingers and thumbs of opposite hands are in contact to create a diamond shape between them (Figs 7.7A, B).

Keeping contact with the skin, the fingers are pulled towards the thumbs, creating a roll of tissue (Figs. 7.7C, D).

The thumbs are pushed forwards while the fingers travel backwards so that the tissue rolls away from the therapist (Figs. 7.7E, F).

Care must be taken to avoid pinching the tissues.

The roll of tissue gradually diminishes in size towards the end of the stroke where the fingers and thumbs of each hand make contact.

The following stroke is begun on an adjacent area of tissue and continues until the whole of the area has been covered.

On muscle, the manipulation is applied across the fibres beginning at one end and finishing at the other.

Manipulation: picking up

Procedure

Picking up may be performed with one hand or with two hands working alternately.

The therapist places her hand on the skin with the fingers adducted and the thumb abducted.

The therapist makes a scooping motion with the massaging hand (Figs. 7.8A, B), at the same time bringing the fingers and thumb together to lift the tissues and gently squeeze them (Figs 7.8C, D).

The resultant roll of tissue is then pulled in the opposite direction and taken to the tissue end-feel.

The tissues are released and the next stroke begun in the adjacent area, progressing until the whole of the treatment area has been covered.

Manipulation: shaking

Procedure

Shaking is performed on muscle.

Small muscles may be shaken between the pad of the index finger and thumb.

On large muscles the manipulation is performed with the whole length of the fingers and thumb.

The patient is positioned so that the muscle is in mid-range.

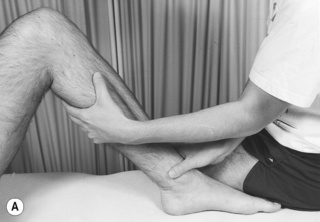

The therapist grasps the belly of the muscle between fingers and thumb and lifts it away from the underlying bone (Fig. 7.9).

Technique: friction

(Cyriax friction technique is described later in this chapter.)

Features

Manipulation 1

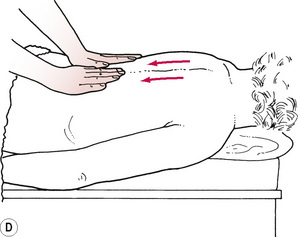

Performed with the whole hand, moving the skin back and forth on the underlying tissues (Fig. 7.10).

Manipulation: friction

Procedure

Manipulation 1

The manipulation may be performed with one hand or two hands working alternately.

The therapist places her hands on the skin with thumb and fingers adducted (Fig. 7.10).

The therapist moves her hands back and forth repeatedly and briskly.

The following stroke begins adjacently and is continued until the whole of the treatment area has been covered.

Manipulation 2

The therapist places the tip of her thumb or finger(s) on the skin over the structure to be treated.

The tissues are compressed to the depth of the structure to be treated.

Small rotary movements are performed on the structure while maintaining a constant pressure.

There is no glide on the skin.

The superficial tissues are moved on the underlying structures.

Technique: tapotement

Manipulation: clapping

Procedure

The therapist's fingers and thumbs are adducted, with the thenar and hypothenar eminences in opposition so that a cup shape is formed by the relaxed hand (Fig. 7.11).

The therapist's elbows are flexed and the arms abducted.

The arms are alternately flexed and extended so that the borders of the hands and fingers strike the skin.

The strokes are rapid, light and brisk.

Air is trapped between the hands and the skin, and produces a hollow sound as contact is made.

Manipulation: hacking

Procedure

The therapist's arms are abducted and her elbows flexed to near 90° (Figs. 7.12A, B).

Her wrists are fully extended and the fingers relaxed (Figs. 7.12C, D).

Her hips are flexed so that the shoulders are over the area to be treated.

The medial borders of the hands and fingers strike the skin alternately, lightly and rapidly.

The movement is at the radio-ulnar joint, which pronates and supinates.

Very light hacking is performed by the fingers only striking the skin.

Manipulation: pounding

Procedure

The therapist's arms are abducted and her elbows flexed to near 90°.

Her wrists are extended and the fingers flexed loosely into a fist (Fig. 7.13).

Her hips are flexed so that the shoulders are over the area to be treated.

The medial borders of the fifth fingers strike the skin alternately and rapidly.

The movement is at the radio-ulnar joint, which pronates and supinates.

Manipulation: vibration

Procedure

The manipulation is performed with one hand.

The therapist's shoulder is abducted and the elbow is slightly flexed.

The hand is placed on the skin with fingers adducted (Fig. 7.14).

The tissues are alternately compressed and released while performing small oscillations by movement of the whole arm, which produces a trembling effect.

The vibration travels through the patient's tissues.

When working in small areas, the fingertips may be used to perform the manipulation.

Technique: neuromuscular technique

Manipulation: neuromuscular technique

Procedure

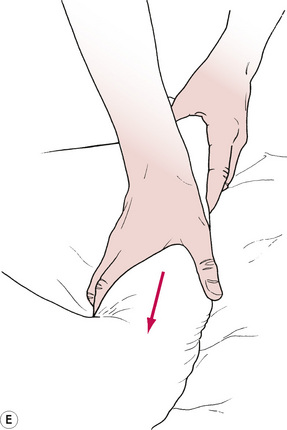

The web space between the therapist's thumb and index finger should be stretched.

The therapist's finger and thumb tips should be placed on the patient's skin.

The thumb should be slid slowly 5–8 cm towards the fingers (Fig. 7.15).

The fingers are then lifted off the skin and moved away from the thumb.

The stroke is then repeated, overlapping with the previous one.

Lesions found are treated by a repetitive application of the stroke or other appropriate techniques.

The stroke can be applied with the fingers if the thumb is too large for any area.

Technique: deep transverse frictions (cyriax friction massage)

This is a specialised technique developed by Dr James Cyriax for the treatment of soft tissue lesions. It is a very specific, localised technique applied to the point of injury of a structure. It is aimed at producing a widthways stretching across the fibres, separating them to lengthen the cross-bridges between collagen fibres, restoring interfibre mobility. This has the effect of restoring longitudinal stretch and widthways expansion to the structure, allowing the broadening of a contracted muscle. The stress applied by this technique ensures that remodelling of connective tissue is stimulated appropriately by precipitating plasticity of molecular bonding in the linear region of the stress–strain curve. Frictions are said to produce a reactive hyperaemia (Chamberlain 1982), which can be useful in healing and chronic scarring.

Frictions should be applied at the correct phase of healing. If they are used too early (within 48 hours of injury), the delicate fibrous network may be disturbed. However, beyond that stage, movement is important as it helps to limit adhesions and scar formation by encouraging proteoglycan synthesis and stimulating new collagen fibres to be aligned in the direction of stress.

The technique is well described in orthopaedic medicine textbooks (Cyriax & Cyriax 1993, Ombregt et al 1995). In addition, there is a limited amount of good research literature on the subject (Stasinopoulos & Johnson 2004). De Bruijn (1984) assessed the onset and duration of the analgesic effects by treating 13 patients with a variety of soft tissue injuries by deep transverse frictions (DTFs). He reported that the range in duration of friction massage was 0.4–5.1 (average 2.1) minutes before analgesia was achieved. In 10 sessions with five patients, the post-massage analgesia lasted between 0.3 minutes and 48 hours (mean 26 hours). It is postulated that the analgesic effect is useful as it facilitates earlier movement following soft tissue injury. Troisier (1991) used DTFs to the common extensor tendon below the epicondyle in 131 patients suffering from tennis elbow. ‘Good and excellent’ results were achieved in 63% of patients. Unfortunately the English abstract of this French paper does not give further detail of the study or method of measuring improvement. A further study (Pellechia et al 1994) compared two regimens in the treatment of patellar tendinitis. The first comprised iontophoresis (movement of a drug through the skin by the application of an electrical current) of dexamethasone and lidocaine (lignocaine). The second protocol consisted of transverse frictions, moist heat and phonophoresis (movement of a drug through the skin by the application of ultrasound) of 10% hydrocortisone and a cold pack. Some 17 men and 9 women were studied, age range 14–43 years. Symptoms had been present between 3 days and 10 years. They received six sessions and were changed to the other protocol if the symptoms persisted at session 7. Iontophoresis showed significant improvement in measures of a visual analogue pain scale, a functional index questionnaire, a rating of palpation tenderness and the number of step-ups needed to elicit pain. Only the last measure improved significantly following the combination treatment protocol. The conclusion reached was that iontophoresis is the most effective treatment. Obviously, this study did not examine the separate components of the combined treatment. Further work to analyse this programme would be useful. A more curious study was undertaken in which changes in biting force were measured following DTFs to the masticatory muscles of 10 cerebrovascular accident victims. The improvement in bite was primarily attributed to facilitation of muscle tone (Iwatsuki et al 2001), although there were no differences between affected and non-affected sides.

Other research has attempted to demonstrate the exact effects of DTFs. Walker (1984) studied the effects of frictions on the healing of a minor sprain in the medial collateral ligament of the rabbit. Twelve rabbits received a sprain on the right side; the left sides were used as healthy controls. A further six rabbits were additional untreated controls. Tissue samples showed no differences between treated and untreated ligaments. Unfortunately, there were no clinical signs of inflammation following the sprains. The earliest any of the tissues was examined following injury was 11 days, in which case healing would be well advanced in a small animal. As there were no differences between sprained and unsprained ligaments, the injuries may have been too negligible to have been influenced by this technique. Unfortunately, then, this study does not enhance our knowledge of the effects of DTFs.

A Cochrane systematic review concluded that there is no evidence of clinically important benefits of DTFs for treating iliotibial band syndrome, but acknowledged that more studies are needed before any conclusions relating to practice can be drawn (Brosseau et al 2002). (See Chapter 13 for discussion of the use of DTFs in bursitis.)

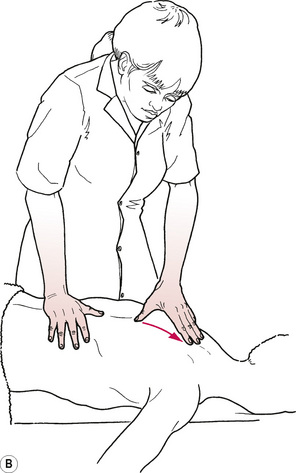

Manipulation: deep transverse frictions

Features

Must be applied accurately to the exact site of damage.

Must be applied at 90° to the direction of the fibres, across the structure.

Must take the tissues through their full sweep, i.e. to their end-feel.

The skin must move with the therapist's fingertips.

The patient must be warned that the technique will be painful until numbing is achieved (after approximately 2 minutes).

Position

Patient

Comfortable, fully supported, body position.

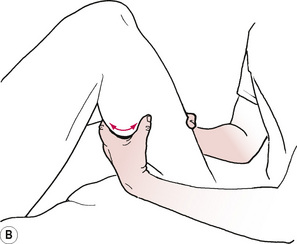

Structure exposed, e.g. shoulder laterally rotated for infraspinatus tendon (Figs. 7.16A, B); internally rotated for supraspinatus.

Ligaments—on stretch (Figs. 7.16C, D).

Tendons without sheath—either taut or short (Figs. 7.16E, F).

Procedure

Contact made between pad of index or middle finger.

Reinforce with adjacent finger.

Apply counterpressure with the other hand.

Sweep back and forth across the lesion using the large muscles of the arm.

Ensure the therapist's fingertips and patient's skin move together.

A full sweep should be achieved—to the end-feel of the tissue.

Continue for up to 15 minutes (expect a numbing effect after about 2 minutes).

Akhondzadeh S., Kashani L., Fotouhi A., et al. Comparison of Lavandula angustifolia Mill. tincture and imipramine in the treatment of mild to moderate depression: a double-blind, randomized trial. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2003;27(1):123-127.

Albert-Puleo M. Fennel and anise as estrogenic agents. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 1979;2:337-344.

Anderson C., Lis-Balchin M., Kirk-Smith M. Evaluation of massage with essential oils on childhood ectopic eczema. Phytother. Res.. 2000;14(6):452-456.

Aqel M.B. Relaxant effect of the volatile oil of Romarinus officinalis on tracheal smooth muscle. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 1991;33:57-62.

Arras G., Usai M. Fungitoxic activity of 12 essential oils against four postharvest citrus pathogens: chemical analysis of thymus capitatus oil and its effect in subatmospheric pressure conditions. J. Food Prot.. 2001;64(7):1025-1029.

Arweiler N.B., Donos N., Netuschil L., et al. Clinical and antibacterial effect of tea tree oil—a pilot study. Clin. Oral Investig.. 2000;4(2):70-73.

Atanassova-Shopova S., Roussinov K., Boycheva I. On certain central neurotropic effects of lavender essential oil. II. Communication: studies on the effects of linalool and of terpineol. Bulletin of the Institute of Physiology. 1973;15:149-156.

Bassett I.B., Pannowitz D.L., Barnetson R. A comparative study of tea tree oil versus benzoylperoxide in the treatment of acne. Med. J. Aust.. 1990;153:455-458.

Brosseau L., Caslmiro L., Milne S., et al. Deep transverse friction massage for treating tendinitis: a systematic review. Cochrane Library. (issue 1):2002. Oxford

Carson C.F., Riley T. The antimicrobial activity of tea tree oil [letter]. Med. J. Aust.. 1994;160:236.

Chamberlain G.J. Cyriax's friction massage: a review. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther.. 1982;4(1):16-22.

Christoph F., Kaulfers P.M., Stahl-Biskup E. A comparative study of the in vitro antimicrobial activity of tea tree oil s.l. with special reference to the activity of beta-triketones. Planta Med.. 2000;66(6):556-560.

Clerc A., et al. Experiments on dogs with certain substances which lower the surface tension of the blood. Current Reviews of Society of Biology. 1934;116:864-867.

Cooke B., Ernst E. Aromatherapy: a systematic review. Br. J. Gen. Pract.. 2000;50(455):444-445.

Craig J.O., Frase M.S. Accidental poisoning in childhood. Arch. Dis. Child.. 1953;28:259-267.

Cyriax J.H., Cyriax P.J. Cyriax's Illustrated manual of orthopaedic medicine, second ed. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1993.

Dale A., Cornwell S. The role of lavender oil in relieving perineal discomfort following childbirth: a blind randomized clinical trial. J. Adv. Nurs.. 1994;19(1):89-96.

De Bruijn R. Deep transverse friction: its analgesic effect. Int. J. Sports Med.. 1984;5:35-36.

Demain S. Departmental danger of death [letter]. Physiotherapy. 1996;82(1):71.

Elliot C. Tea tree oil poisoning [letter]. Med. J. Aust.. 1993;159:830-831.

Ewan P. Clinical study of peanut and nut allergy in 62 consecutive patients. Br. Med. J.. 1996;312:1074-1077.

Graham P.H., Browne L., Cox H. Inhalation aromatherapy during radiotherapy: results of a placebo-controlled double-blind randomized trial. J. Clin. Oncol.. 2003;21(12):2372-2376.

Hills J.M., Aaranson P.I. The mechanism of action of peppermint oil on gastro-intestinal smooth muscle. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:55-65.

Iwatsuki H., Ikuta Y., Shinoda K. Deep friction massage on the masticatory muscles in stroke patients increases biting force. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2001;13(1):17-20.

Kaddu S., Kerl H., Wolf P. Accidental bullous phototoxic reactions to bergamot aromatherapy oil. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.. 2001;45(3):458-461.

Khanna M., Qasam K., Sasseville D. Allergic contact dermatitis to tea-tree oil with erythema multiform-like id reaction. Am. J. Contact Dermat.. 2000;11(4):238-242.

Lawless J. The encyclopaedia of essential oils. Shaftesbury, Dorset: Element, 1992.

Lazutka J.R., Mierauskiene J., Slapsyte G., et al. Genotoxicity of dill (Anethum graveolens L.), peppermint (Menthaxpiperita L.) and pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) essential oils in human lymphocytes and Drosophila melanogaster. Food Chem. Toxicol.. 2001;39(5):485-492.

Lehrner J., Eckersberger C., Walla P., et al. Ambient odor of orange in a dental office reduces anxiety and improves mood in female patients. Physiol. Behav.. 2000;71(1–2):83-86.

Lis-Balchin M., Hart S.L., Deans S.G. Pharmacological and antimicrobial studies on different tea-tree oils (Melaleuca alternifolia, Leptospermum scoparium or Manuka and Kunzea ericoides or Kanuka), originating in Australia and New Zealand. Phytother. Res.. 2000;14(8):623-629.

Martin K.W., Ernst E. Herbal medicines for treatment of fungal infections: a systematic review of controlled clinical trials. Mycoses. 2004;47(3–4):87-92.

Mozelsio N.B., Harris K.E., McGrath K.G., et al. Immediate systemic hypersensensitivity reaction associated with topical application of Australian tea tree oil. Allergy Asthma Proc.. 2003;24(1):73-75.

Olleveant N.A., Humphris G., Roe B. How big is a drop? A volumetric assay of essential oils. J. Clin. Nurs.. 1999;8(3):299-304.

Ombregt L., Bisschop P., ter Veer H.J., et al. A system of orthopaedic medicine. London: W B Saunders, 1995.

Patzelt-Wenczler R., Ponce-Poschl E. Proof of efficacy of Kamillosan cream in atopic eczema. Eur. J. Med. Res.. 2000;5(4):171-175.

Pellechia G.L., Hamel H., Behnke P. Treatment of infrapatellar tendinitis: a combination of modalities and transverse friction massage versus iontophoresis. J. Sport Rehabil.. 1994;3:135-145.

Prashar A., Locke I.C., Evans C.S. Cytotoxicity of lavender oil and its major components to human skin cells. Cell Prolif.. 2004;37(3):221-229.

Rho K.H., Han S.H., Kim K.S., et al. Effects of aromatherapy massage on anxiety and self-esteem in Korean elderly women: a pilot study. Int. J. Neurosci.. 2006;116(12):1447-1455.

Roe F.J.C., Field W.E.H. Chronic toxicity of essential oils and certain other products of natural origin. Food Cosmet. Toxicol.. 1965;3:311-324.

Saeki Y. The effect of foot-bath with or without the essential oil of lavender on the autonomic nervous system: a randomized trial. Complement. Ther. Med.. 2000;8(1):2-7.

Satchell A.C., Saurajen A., Bell C., et al. Treatment of interdigital tinea pedis with 25% and 50% tea tree oil solution: a randomized, placebo-controlled, blinded study. Australas. J. Dermatol.. 2002;43(3):175-178.

Schaller M., Korting H.C. Allergic airborne contact dermatitis from essential oils used in aromatherapy. Clin. Exp. Dermatol.. 1995;20(2):143-145.

Skiba B. The mineral oil myth. Massage. 1993;44:40-41.

Snow L.A., Hovanec L., Brandt J. A controlled trial of aromatherapy for agitation in nursing home patients with dementia. J. Altern. Complement. Med.. 2004;10(3):431-437.

Solanki K., Matnani M., Kale M., et al. Transcutaneous absorption of topically massaged oil in neonates. Indian Pediatr.. 2005;42(10):998-1005.

Stasinopoulos D., Johnson M.I. Cyriax physiotherapy for tennis elbow/lateral epicondylitis. Br. J. Sports Med.. 2004;38:675-677.

Sugiura M., Hayakawa R., Kato Y., et al. Results of patch testing with lavender oil in Japan. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;43(3):157-160.

Taylor J.M. Fennel. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol.. 1964;6:378-387.

Tisserand R. The art of aromatherapy. Essex: C W Daniel, 1994.

Tisserand R. Essential oil safety. I. International Journal of Aromatherapy. 1996;7(3):28-32.

Tisserand R., Balacs T. Essential oil safety: a guide for health professionals. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1995.

Troisier O. Les tendinites epicondyliennes. Rev. Prat.. 1991;41(18):1651-1655.

Varman S., Walker A. Introduction to aromatherapy for physiotherapists [course notes]. Norwich: University of East Anglia, 1995.

Walker J.M. Deep transverse frictions in ligament healing. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther.. 1984;62:89-94.

Young A.R., Walker S.L., Kinley J.S., et al. Phototumorigenesis studies of 5-methoxypsoralen in bergamot oil: evaluation and modification of risk of human use in an albino mouse skin model. J. Photochem. Photobiol.. 1990;7:231-250.

Zatz J.L. Scratching the surface: rational and approaches to skin permeation. In: Zatz J.L., editor. Skin permeation: fundamentals and application. Wheaton: Allured, 1993.