Chapter 9 Eliminative behavior

Chapter contents

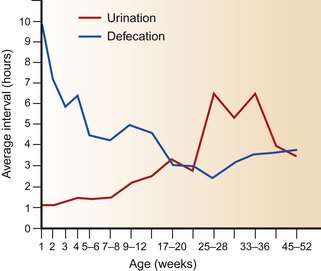

Development of eliminative responses

As a reflection of the changing nature of water balance from neonate to juvenile and the concurrent shift in diet, the frequency of urination decreases as that of defecation increases with maturity (Fig. 9.1). By 5 months of age, defecation has plateaued from approximately twice per day in the first week of life so that it occurs every 3–4 hours.1 Urination, on the other hand, declines from an hourly event to one that occurs about six times per day.1 Perhaps because they can tolerate greater distensions of their bladders, filly foals are generally twice as old as colts when they first urinate (10.77 hours post-partum versus 5.97).2

Defecation

Horses can be prompted to defecate by the sight of feces or the action of another horse defecating. Drinking is also thought to provide a stimulation to dung,3 possibly via a gastro-colic reflex.4 Arousal in the form of both fear and excitement can also stimulate horses to defecate,5 sometimes to the extent of intestinal hurry, as manifested by the presence of undigested grain. It is currently unclear whether feces and urine from fearful horses provide olfactory warning cues to conspecifics, as has been shown in cattle and pigs.6,7

Horses tend to show considerable care in selecting defecation sites since they return repeatedly to areas that are not used for grazing. Fecal material makes the grass in latrine areas less appealing, even though the grass itself is readily consumed if presented to horses without the fecal material.8 This response, which develops in foals as they mature and become less attached to their dams,9 prompts the development of so-called latrine and lawn areas.1 The tendency to defecate in soiled areas means the main body of pasture carries fewer parasites. This strategy is appropriate for free-ranging horses that have a virtually unlimited range but in smaller fenced grazing areas it behoves management to institute rotational grazing to break the lifecycle of endoparasites.

The vestiges of dunging strategy are sometimes evident in stabled horses that show an attempt to select sites. As noted by Mills et al,10 when given the choice between two bedding substrates in looseboxes joined by a passageway, horses defecated in the passageway more than in either box. This could reflect the association between movement (between boxes when exercising choice) and hindgut motility, but should prompt further investigation into the aversiveness felt by horses to fecal material and the extent to which welfare may be compromised by making horses stand in close proximity to their own excrement for extended periods, as is the case in standard husbandry. Certainly, pastured horses tend to move forward after defecation.9 Porcine studies have provided a possible model by demonstrating the olfactory threshold of the pigs for concentrations of ammonia in the air.11 Since urine and fecal material may be offensive, not least because of their ammonia content but also because they attract flies, compounds such as sodium bisulfate that have been shown to decrease ammonia concentrations and behavior typical of horses being bothered by flies should be integrated in the stable hygiene routine.12

Some owners who note that their horses (often geldings rather than mares) repeatedly defecate in feed buckets, sometimes interpret this behavior as a form of protest. A more likely explanation is the establishment of a habitual dunging pattern that coincides with relatively little space and therefore few alternatives other than that in which the receptacle is routinely placed. Hanging the haynet over the favored site (and ensuring that plenty of hay is contained within it) is usually effective in keeping the horse oriented appropriately and capitalizing on the innate equine tendency to move away from a foraging site prior to defecation. Despite such efforts, some horses do seem to target their food and water receptacles and repeatedly compromise their own ingestive activities as a result. Intriguingly, it appears that Thoroughbreds are more likely to perform this behavior than other breeds.13 Ethologists note that the response is seen mainly in buckets that are placed on the wall next to the stable door and suggest that barrier frustration may contribute to the etiology.13

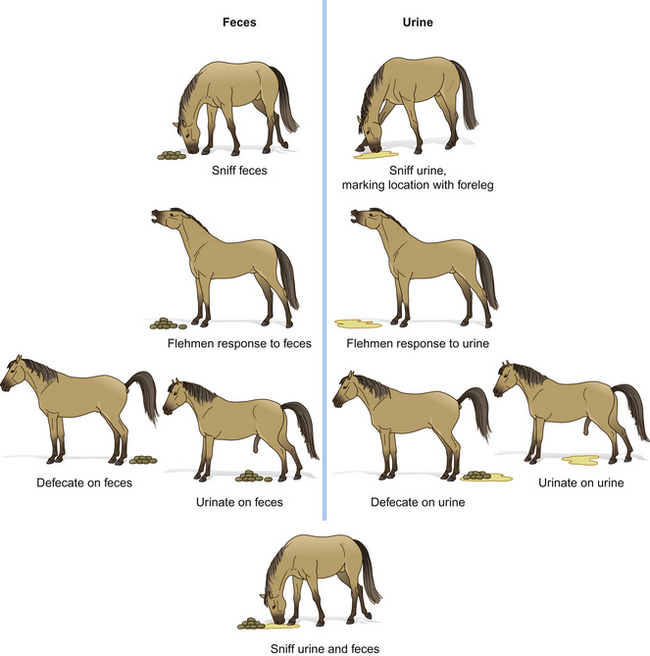

Despite the rarity of territories, stallions indicate their presence by piling their feces. About 25% of interactions between stallions occur in the vicinity of fecal piles (see Ch. 6).14 Regular marking by stallions and dung-pile rituals are effective means of avoiding fighting and confrontation between stallions. As a cardinal feature of such interactions, a behavioral sequence that includes defecation is performed by them, either in succession or in unison.15 It has been suggested that the dominant stallion is usually the last to defecate on the pile.16 The culmination of these rituals is mutual passive withdrawal, the subordinate being pushed away, or a full-scale fight. The sequence of behaviors targeted on the pile runs as follows:

The entire sequence, or elements within it, are repeated.

In the free-ranging state, dung piles may serve as orientation marks for stallions. Domestic stallions often accumulate fecal piles beside fencelines because this is the nearest they can get to conspecifics.17 Occasionally, geldings create fecal piles,9 but greeting rituals involving them have not been reported. Whereas stallions usually move over fecal material and defecate or urinate on top of it (Fig. 9.2), mares and, to a lesser extent, geldings tend to sniff feces within latrine areas and defecate without much movement. This has the effect of spreading the area of rank grass6,18,19 and the resultant repugnance and lack of close cropping facilitates the growth of weed species, including thistle (Cirsium spp.) and ragwort (Senecio jacobaea).6,20

Figure 9.2 The elimination/marking sequence of harem stallions involves voiding feces and urine after the olfactory investigation of urine and feces recently voided by harem members.

(After McDonnell SM. A Practical Field Guide to Horse Behavior – The Equid Ethogram. Lexington, KT: The Blood Horse Inc; 2003.)

Urination

As with defecation, horses prefer to visit latrine areas to urinate. However, movement toward latrine areas occurs less reliably prior to urination than it does prior to defecation.9 The number of urinations per day is related to water intake but, because of water loss through sweating, it is also negatively correlated with temperature and exercise.3

Generally mares and stallions adopt a similar posture before urinating. The croup is lowered and the tail is raised, with the hindlegs abducted and extended posteriorly. Both colts and fillies are sometimes seen urinating on top of fecal material.1 While this trait disappears in females as they approach puberty, it becomes more obvious in males. When a stallion encounters a mare’s dung, he urinates on it, apparently in a bid to mask its odor.21 After being turned-out, some stallions mark with their urine as a priority ahead of greeting conspecifics.8

Mares are sometimes seen spurting urine, for example, in combination with kick threats when herded by stallions. Urination in mares becomes elaborate when they are in estrus, since they maintain a straddled stance for longer periods than when in anestrus and often tilt their hindtoes until one no longer bears weight (Fig. 9.3). This stance may act as an inviting visual signal for stallions since they have been observed rushing excitedly toward urinating mares.1 In pony mares the tail is generally not held to one side as it is by horse mares.22 The clitoral winking that occurs in all mares after urination is far more frequent when they are in estrus. In estrus, mares also pass less urine at each urination.22 Urination often occurs as a spontaneous solicitation and in response to teasing.23

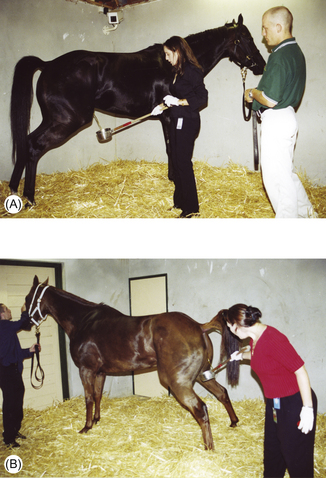

In an apparent bid to avoid having their legs splashed by their own urine, horses select soft substrates on which to urinate. This is thought to be the origin of straw being a classically conditioned stimulus for urination in stabled horses. The association is routinely used to aid urine collection in performance horses (Fig. 9.4). Bedding is often removed from stables during the day for hygiene or economy reasons. While laudable if used only as a means of drying the stable floor while the horse is at pasture, this intervention can have unwelcome consequences if the horse remains in the stable without bedding since it deters both recumbency and urination. The growing trend towards the use of rubber matting in place of traditional bedding substrates may have similar effects on the inclination to urinate and merits investigation. A similar impediment to comfortable urination is thought to apply to urban horses, such as draft animals used in cities for tourism.

Figure 9.4 (A) Gelding and (B) mare providing post-race urine samples. Familiar bedding materials and whistling are used as classically conditioned stimuli for urination in racehorses. Anecdotal evidence suggests that females are less easy to train to urinate on cue than males.

Increased frequency of urination has been noted as an indicator of social distress in isolated horses.24 Although it may reflect urinary calculi and cystitis,25 polyuria is usually a consequence of polydipsia that can be organic or psychogenic in origin (see Ch. 8). The usual presenting sign is an excessively wet bed. Determining water intake is an important step in defining the extent of the problem, and direct observation of the horse’s drinking and eating behavior can help to identify contributing behavioral anomalies such as excessive use of salt licks.

References

1. Tyler SJ. The behaviour and social organization of the New Forest ponies. Anim Behav Monogr. 1972;5:85–196.

2. Jeffcott LB. Observations on parturition in pony mares. Equine Vet J. 1972;4:209–213.

3. Schafer M. The language of the horse. London: Kaye & Ward, 1975.

4. Ganong WF. Review of medical physiology, 14th edn. California: Lange Medical Publications, 1989.

5. Houpt KA, Hintz HF, Pagan JD. Maternal-offspring bond of ponies fed different amounts of energy. Nutr & Behav. 1983;1:157–168.

6. Boissy A, Terlouw C, Neindre PL. Presence of cues from stressed conspecifics increases reactivity to aversive events in cattle: evidence for the existence of alarm substances in urine. Physiol Behav. 1998;63:489–495.

7. Vieuille-Thomas C, Signoret JP. Pheromonal transmission of an aversive experience in domestic pig. J Chem Ecol. 1992;18:1551–1557.

8. Kiley-Worthington M. The behaviour of horses in relation to management and training. London: JA Allen, 1987.

9. Ödberg FO, Francis-Smith K. A study on eliminative and grazing behaviour – the use of the field by captive horses. Equine Vet J. 1976;8(4):147–149.

10. Mills DS, Eckley S, Cooper JJ. Thoroughbred bedding preferences, associated behaviour differences and their implications for equine welfare. Anim Sci. 2000;70(1):95–106.

11. Jones JB, Wathes CM, Persaud KC, et al. Acute and chronic exposure to ammonia and olfactory acuity for n-butanol in the pig. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2001;71(1):13–28.

12. Sweeney CR, McDonnell S, Habecker PL, Russell GE. Effect of sodium bisulfate on ammonia levels, fly population and manure pH in a horse barn. Proc AAEP. 1996;42:306–307.

13. Perry PJ, Houpt KA. Aetiology of faecal soiling of buckets by horses. In: Overall KL, Mills DS, Heath SE, Horwitz D. Proceedings of the Third International Congress on Veterinary Behavioural Medicine. UK: UFAW; 2001:139–141.

14. Miller R. Male aggression, dominance and breeding behaviour in Red Desert feral horses. Z Tierpsychol. 1981;64:97–146.

15. McDonnell SM. Haviland JCS. Agonistic ethogram of the equid bachelor band. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1995;43:147–188.

16. McCort WD. Behaviour of feral horses and ponies. J Anim Sci. 1984;58(2):493–499.

17. McDonnell S. Reproductive behavior of stallions. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract: Behav. 1986:535–555.

18. Carson K. Wood-Gush DGM. Equine behaviour, ii: A review of the literature on feeding, eliminative and resting behaviour. Appl Anim Ethol. 1983;10:179–190.

19. Rees L. The horse’s mind. London: Stanley Paul, 1984.

20. Edwards PJ, Hollis S. The distribution of excreta on New Forest grassland used by cattle, ponies and deer. J Appl Ecol. 1982;19(3):953–964.

21. Kimura R. Volatile substances in feces, of feral urine and urine-marked feces of feral horses. Can J Anim Sci. 2001;81(3):411–420.

22. Asa CS. Sexual behavior of mares. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract: Behav. 1986:519–534.

23. Fraser AF. The behaviour of the horse. London: CAB International, 1992.

24. Strand SC, Tiefenbacher S, Haskell M, et al. Behaviour and physiologic responses of mares to short-term isolation. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2002;78:145–157.

25. Waring GH. Horse behavior: the behavioral traits and adaptations of domestic and wild horses including ponies. Park Ridge, NJ: Noyes, 1983.