Chapter 6 Communication

Chapter contents

Body language

Monitoring of Przewalski horses has shown that a band’s behavior can be synchronized between 50% and 98% of the time.1 Communication between members of a social group of horses facilitates this synchrony. Horses most often communicate without using their voices. This is because they are social prey animals that must organize themselves as a group but without attracting predators. Used to scan for responses after vocalization, the ears are the most important body part in equine non-vocal communication. When flattened, they generally qualify all concurrent interactions as agonistic, and the extent to which they are pinned back correlates with the gravity of a threat.2 An important feature of bite threats, ear pinning may have evolved simply as a means of avoiding ear injury during fighting, but it has taken on an additional signaling function. Rather than being pinned back, ears are simply turned to point backwards during avoidance responses as horses retreat as a display of submission.3

Ears are not central to expressions of threatened aggression alone. Indeed they are focal to a series of expressions elegantly described by Waring & Dark.4 Neck posture changes significantly during agonistic encounters between horses, being flexed during approach responses and often arched in response to threats, especially by stallions.3 It is important to note that such arching is extremely transient and therefore cannot plausibly be cited as a natural analogue of the prolonged hyperflexion seen in Rollkur or so-called long-deep-and-round training.5 Head bowing that involves rhythmic exaggerated flexing of the neck to the extent that the muzzle may touch the pectoral region is seen as a synchronous display by two stallions as they approach one another head to head.3

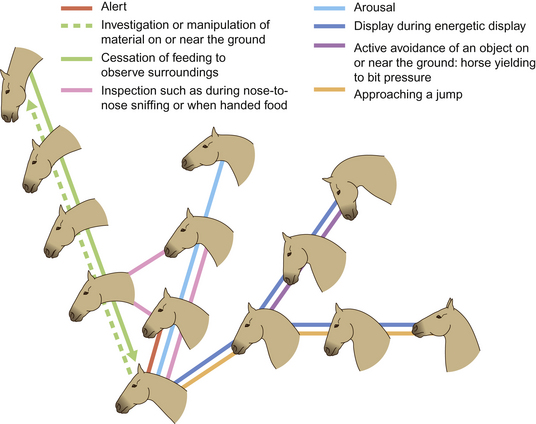

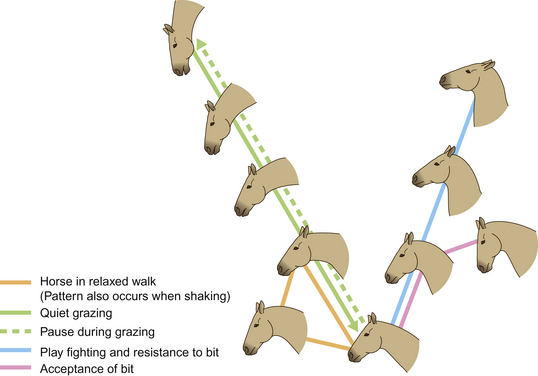

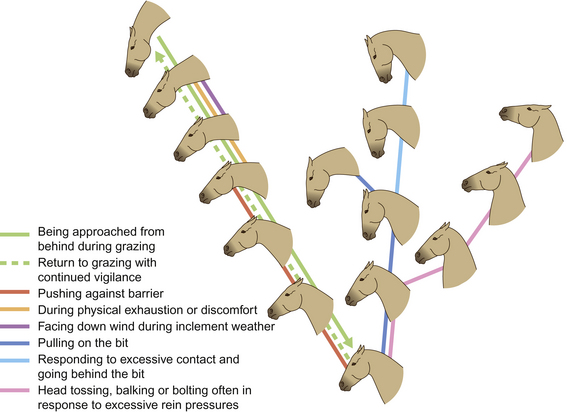

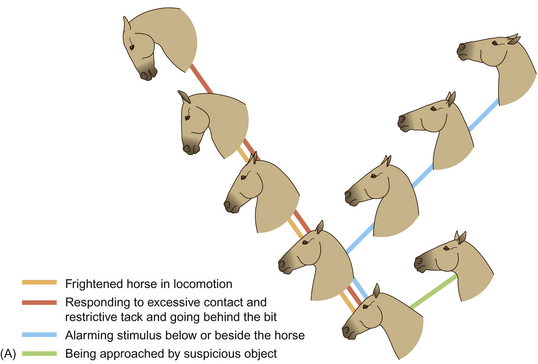

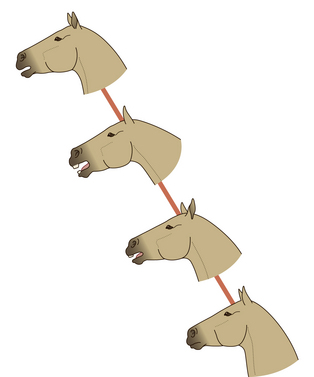

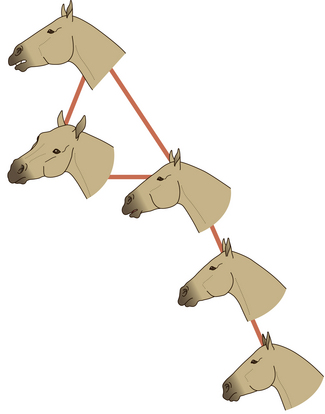

The series of illustrations in this chapter demonstrates the importance in communication of various features of the equine head, including the nostrils or nares. The nares dilate and constrict with changes in mood. For example, during forward attention, as a horse sniffs the ground, they are moderately dilated whereas during aggression they become drawn back to form wrinkles on their aboral edge. In combination with head position, the ears and nares contribute to expressions of forward attention (Fig. 6.1), lateral attention (Fig. 6.2), backward attention, alarm, aggression, submission and pleasure.

Figure 6.1 Expressions of forward attention.

(Redrawn from Waring2, after Waring & Dark4, with permission.)

Figure 6.2 Expressions of lateral attention.

(Redrawn from Waring2, after Waring & Dark4, with permission.)

When ears are pointing forward the horse is, as one might expect, attending to a stimulus in front of it. Horses are sometimes seen pointing their ears in two directions (see, for example, Fig. 2.14 on p. 48). Swiveling of the ears is associated with pain; e.g. a horse with colic may swivel its ears back in the direction of its abdomen before it gets to the stage of kicking at its belly.

The positions of horses’ ears in a moving band seems to be predicated on the spatial positions of those horses in the group. Horses at the front of a moving group tend to have their ears forward while those to the rear orient their ears backwards. This suggests that, in this instance, ears are used chiefly for surveillance rather than for signaling. To that extent, horses that are not leading may have the rear under surveillance (Fig. 6.3). This strategy makes sense for the safety of the group since it allows the leaders to concentrate on hazards ahead of the group. Some racehorse trainers use blinkers to reduce the influence of other horses (Fig. 6.4).

Figure 6.3 Expressions of backward attention.

(Redrawn from Waring2, after Waring & Dark4, with permission.)

Figure 6.4 A racehorse wearing blinkers to modify its flight response and reduce distraction from other horses.

(Photo courtesy of Sandra Jorgensen.)

When horses are frightened by or simply suspicious of a stimulus, their alarm is often indicated by switching the direction of the ears and by a tense mouth and dilated nostrils. Alarmed horses tend to withdraw from such stimuli with rather jerky movements that alert conspecifics and contribute as a survival strategy because they confound a predator’s ability to predict the horse’s intended route of escape. The same unpredictable responses can make frightened horses dangerous to lead and ride and thus alarm conspecific companions (see Ch. 15).

Aggressive horses look similar to alarmed horses (Fig. 6.5). Indeed, one expression can give rise to the other, except that aggressive horses tend to pin their ears back and wrinkle the aboral edge of their nares, sometimes to the extent that their teeth are exposed. When driving his mares (see Ch. 11), a stallion feigns snapping2 and drops his head below the horizontal with additional nodding and swinging movements. These embellishments to the posturing of regular aggression represent expressive movements that qualify the signal as a driving cue rather than direct aggression.

Figure 6.5 Expressions of (A) alarm and (B) aggression.

(Redrawn from Waring2, after Waring & Dark4, with permission.)

The reasons for horses to signal submission have been dealt with in the previous chapter but it is worth emphasizing that, in the midst of a conflict between horses, it is often the appeasement signals that determine the outcome. These may be very subtle. Mindful of the example offered by Clever Hans (see Ch. 4), we would do well to remember that, with their excellent vision, horses are able to detect minute cues in animals around them. When submitting, a horse will look away from the threat and try to shuffle away, often with its croup and tail lowered. If trapped in a melée, submissive horses raise their heads and often show the whites of their eyes.

Head nodding forms part of the greeting a stallion makes when he approaches a new mare or a mare that may be in estrus. Head lowering and lip-licking have been identified as signs of submission in roundpen exercises and indeed they tend to precede movement of the horse towards the trainer. Because these responses have not been recorded in scientific literature on studies of free-ranging horses, it remains difficult to interpret them. Therefore there is a need for studies of physiological responses that coincide with such behaviors. It is possible that these behaviors are not so much signals as signs of conflict. Regardless of their true meaning, the trainer can capitalize on these responses by withdrawing to reinforce appropriate behaviors. For example, when the horse slows down or looks towards the trainer after showing these responses, the trainer can reward the horse by retreating and reducing the threats offered by his posture.

Although still the source of some controversy, the snapping action of youngsters is regarded as an attempt to communicate (Fig. 6.6). The extent to which it is successful remains unclear. Since prevalence is inversely correlated with the age of the performer, it may be that its relevance wanes as its refinement peaks. It is not offered exclusively to horses, having been observed being offered to cows, humans and horse-rider pairs. Although sometimes accompanied by sucking and tongue clicking sounds, it is chiefly a visual signal that is marked by the assumption of a characteristically extended neck, head lowering and exposure of the teeth.2 The performer often lolls its ears laterally but maintains visual focus on its target.

Figure 6.6 Juvenile greeting used on adults.

(Redrawn from Waring2, after Waring & Dark4, with permission.)

While the lips are usually drawn back to expose the incisors during snapping displays, they are often pursed as part of a head threat display.3 The teeth and masseter muscles may be clenched during pain even though the lips may appear loose. The same loose-lipped appearance has been noted in some sexually receptive mares and many older animals.

During mutual grooming, horses often extend the upper lip (Fig. 6.7) and move it from side to side and sometimes tilt their head and swivel their eyes laterally. With the panoramic quality of equine vision, it is possible that a grooming partner is able to detect this response as a signal that it has located a seat of irritation. This response, also seen when a solitary horse uses a scratching post, is sometimes accompanied by deep respiratory excursions and some luxuriant groaning.

Figure 6.7 During pleasurable stimulation the upper lip may extend and twitch and on some occasions the head may turn.

(Redrawn from Waring2, after Waring & Dark4, with permission.)

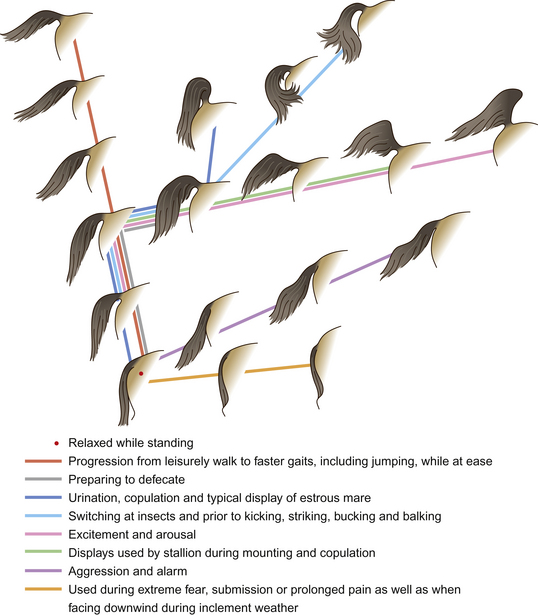

Although rarely used in isolation from other forms of body language, the tail, or more especially its position, is an important indicator of mood or intention (Fig. 6.8). Horses are likely to be able to see the tail of another herd member if they cannot see its ears. So the tail plays a key role when horses are sorting out social spacing while at rest or while grazing in close formation. Tail movements form a characteristic element in kick threats and as such are most commonly seen in play and courtship rather than in disputes over resources such as food or shelter.

As a characteristic of anti-insect responses, swishing movements of the tail are a sign of irritation. Riders often report this response when a horse resists or enters behavioral conflict (see Ch. 13). The significance of tail-swishing in dressage competitions is recognized by the rules, which stipulate that such signs of resistance should attract penalties. However, dressage judges struggle to agree on signs of resistance in horses competing at the elite level.6 Tail-raising is generally associated with the high postural tonus of arousal and an intention to move forward, while tail-lowering signals to observing horses that the bearer is intending to decelerate.7 The tail is also lowered in horses as they withdraw from threatening stimuli. It is unfortunate that, in recognizing the importance of tail carriage in articulating demeanor, humans have chosen to interfere with it for the sake of supposed competitive success in the show ring. For example, in a bid to mask excitement, horses shown as Western pleasure horses, which are judged partly on an absence of reactivity to stimuli, may have their tails deadened by local anesthetic or even neurectomy.8 Similarly, weights are regularly integrated into the tail hairs of show horses to lower the tail carriage (Cameron Wood, personal communication). Conversely, Arabian show horses are expected to have an elevated tail carriage as a measure of their reactivity and therefore, to raise the tail of some unfortunate individuals, irritants such as ginger are inserted per rectum.8 Unfortunately, in contrast to tail deadening, which can be detected by an electromyogram, ‘gingering’ is difficult to confirm.8

These abuses, along with ‘soring’ (the application of caustic material to the pasterns) to accentuate the extension of the forelimbs of Tennessee Walkers8 are more likely to be controlled if veterinarians remain aware of them and prioritize the welfare of the animals in their care. Legislation may have outlawed many such interventions, but policing the emergent rules relies on the cooperation of the profession and greater empowerment of stewards.

Other movements of the tail accompany urination and defecation. Clitoral winking and the increased frequency of urination of mares during estrus serve as visual signals that attract stallions to investigate the performer. Meanwhile, the characteristic flagging of the stallion’s tail during coitus is used by stud managers as evidence of ejaculation.

Lifting of the fore- or hindlegs is used as part of striking or kicking threats, respectively. Pawing is recorded in free-ranging horses as they attempt to unearth hidden water soaks or remove snow from forage. A similar foot-stamping response is seen as a sign of frustration in domestic contexts, e.g. after administration of unpleasant-tasting oral anthelmintics. Pawing is often seen in combination with restraint, especially when a ridden horse is held back from joining the rest of the group, when a horse is denied access to food, or when a stallion is required to wait before approaching a mare in a service area.9 The response can be inadvertently reinforced by feeding10 and can readily be trained as a trick.2

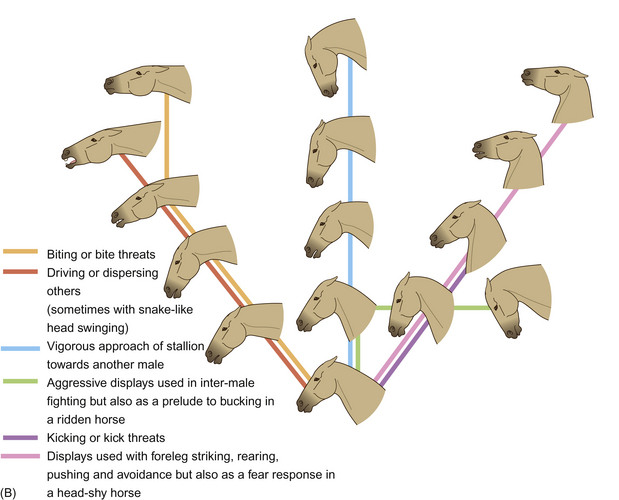

Ritualized displays between stallions

There are generally thought to be five possible steps in the display sequence exchanged by stallions before they get as far as actually fighting.2 Partially driven by the need to prevent mixing of natal bands, these displays are performed at a distance and allow demonstrations of resource-holding potential without combat as a reflection of the possible cost of fighting between stallions. While it should be noted that any element may be omitted, the five steps in the characteristic interactions between stallions are described in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1 Five stages that occur in recurring sequences when stallions meet

| Core response | Additional movements | Vocalization |

|---|---|---|

| Standing and staring at one another while separated | Tail switchingPawing | Whinnying |

| Scanning for other bands | ||

| Ears forward | ||

| Posturing and mobile displays with elevated trotting action | Arching of neckFlexing of the poll | Snorting |

| Nodding | ||

| Tail elevated | ||

| Ears forward | ||

| Pawing of fecal piles | ||

| Sniffing of fecal piles | ||

| Advance towards one another and conduct olfactory investigation during close encounter | Start by sniffing the nostrils and muzzle then often moving over neck, withers, flank, groin, rump and perineum | Snorting followed by sudden squealing |

| Threats and pushing | Bite threats | Squealing |

| Strike threats | ||

| Biting | ||

| Striking | ||

| Circling and occasional hindleg kicking | ||

| Defecating on a fecal pile either one after the other or simultaneously (see Fig. 9.2) | Smelling the pile usually before and after defecation |

After Waring.2

After any stage in the sequence of responses a pair of stallions may separate. After the fecal pile display, the sequence either as a whole or in parts may be revisited. With each sequence, one element may be accentuated and the threats tend to escalate.2

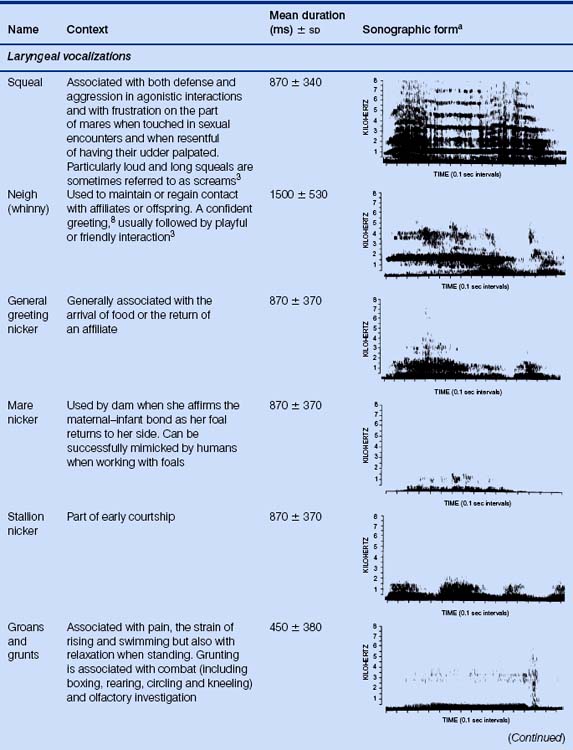

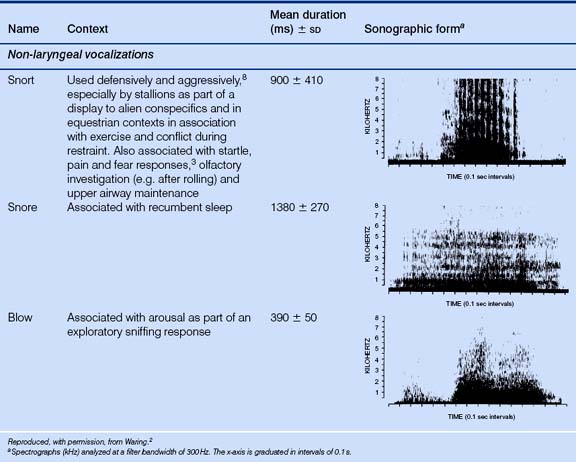

Sounds

Noises produced by the larynx are considered more important in communication between horses than the non-laryngeal noises such as groaning, which are, to an extent, byproducts of the expiratory effort as it passes through the upper airways. For example, groaning is often made by swimming horses, chiefly because the respiratory excursions are made very difficult when the thorax is immersed (David Evans, personal communication 2002). Coughing and sneezing are other sounds linked to upper-airway maintenance. Kiley-Worthington7 notes that waves of sneezing may occur in groups of horses in stables and at exercise. This may be a result of an irritant common to all affected members of the group or may even represent social facilitation. Under-saddle, horses make deep but gentle nasal exhalations when they appear to relax during a training session (Andrew McLean, personal communication).

When they use their voices, horses capitalize on their voluminous sinuses to produce sounds that travel well. Indeed in the case of a stallion, snorts and nickers can be heard from 30 m and 50 m, respectively, while his neigh can be heard by humans 1 km away.2 Depending on the sound that is being produced, the mouth may be opened or closed during vocal communication. For example, squeals are usually emitted through a closed mouth whereas whinnies are generally produced with the mouth slightly open.3 Laryngeal and non-laryngeal vocalizations are considered in Table 6.2.

Other noises made by horses without involvement of the larynx include the rhythmic sloshing sound made by the sheath of some, but not all, males during trotting and the footfalls that other horses use to help locate conspecifics. The sound of footfalls, especially the characteristic pattern emitted when a horse investigates a novel stimulus,2 can communicate the possible need for flight.

Recognition of sounds

Field studies suggest that, by 3 weeks of age, foals can recognize their dam’s neighs.11 Other interesting observations imply that band members may respond only to the calls of affiliates that have been absent from the group for some time.11 The importance of the neigh as a means of connecting affiliates is demonstrated by its increased frequency when one places a horse in unfamiliar company. The sight of another horse often prompts neighing, presumably in a bid to ascertain whether the conspecific is familiar. Like humans, horses seem capable of cross-matching unique auditory and visual/olfactory information from known individuals. In one study, horses watched a herd member being led towards and then behind a screen, before a recorded vocalization from that herd member or from a different affiliate was played from a loudspeaker near the screen.12 Observer horses looked more quickly and for longer when presented with incongruent combinations that violated their expectations, i.e. when they were shown one affiliate before hearing the call of a different affiliate.

By playing back recordings of equine vocalizations, we can begin to measure the extent to which individual calls can be recognized by their intended recipients. Compared with recorded squeals and nickers, neighs elicit more attention.13 There is evidence that mares are better at recognizing recordings of their foal’s calls than vice versa.14

Tactile communication

As social creatures, horses have a behavioral need for tactile communication. Foals are first licked (immediately post-partum), and nuzzled (during suckling) by their dams. In return, mares are regularly nibbled by their offspring in attempts to initiate mutual grooming and play. This sets the pattern for interactions between the pair and with other horses in general. Tactile contact with the conspecific’s shoulder, flank and groin forms a pivotal stage when two horses greet.2 Unfortunately, stable managers often find that meeting the need for tactile contact is made unattractive by the risk of neighbors fighting and causing injuries as they become familiar with one another. The traditional design of standing stalls in coach houses prevented contact by the inclusion of high sides at the head end of the partitions between horses. Abnormal behaviors are commonly associated with stable designs that deny tactile communication between neighbors.15

Communication by odors

Although they very often squeal and strike afterwards, horses sniff each other and each other’s breath as part of greeting and recognition (Fig. 6.9). This had led some authors7 to advocate blowing up the noses of horses as a means of saying ‘hello’. Until we more fully understand the function of the squeal-and-strike epilogue to sniffing, this practice remains appropriate only for experienced personnel, since novices may misread the signals that the horse sends back to this overture and injuries may result.

As demonstrated by the accuracy with which mares can recognize the odor of their own foals, horses use odor to identify group members. Similarly they are sensitive to the odors of alien conspecifics, and this is why they investigate excrement carefully when given the opportunity. When presented with samples of their own feces and those of familiar and unfamiliar conspecifics, horses distinguished their own from conspecifics’ but did not differentiate between familiarity and sex.16 They focused most on the feces of familiar horses from which they had had the greatest amount of aggressive interaction. There is evidence that horses can use urine odor to discriminate between conspecifics, but that the detail that can be garnered from urine may be limited to broad differences, such as sex or reproductive status.17 However, when offered samples of urine, feces and body odor samples (acquired by rubbing fabric on the bodies of conspecifics), mares sniffed the body-odor samples for longer.17

By leaving a sample of urine, mares are able to communicate their proximity to estrus. Stallions investigate mares’ urine using the characteristic flehmen response that is thought to facilitate sampling of pheromones (see Ch. 2).18 Typically, the flehmen response includes rolling back the upper lip, rotating the ears to the side and extending the neck while the head is elevated.3

Estrous urine does not elicit more of a flehmen response than non-estrous urine, so it seems that visual displays including an increased rate of urination in estrous mares and their clitoral winking help to excite the stallion’s interest in their deposits.19,20 Approximately 50% of female urinations may be inspected by the natal band stallion.21 His usual response after sampling the volatile odors from the urine is to walk forward slightly, urinate on top of the mare’s urine and then turn to sample the composite odor that remains. The composition of stallion urine varies in its fatty acid, phenol, alcohol, aldehyde, amine and alkane content according to maturity, sex and stage in the breeding season.22 Because of the high concentration of cresols in the urine of stallion urine during the breeding season it has been suggested that one role of urinating on top of a mare’s feces is to mask their odor and presumably thus thwart other stallions’ attempts to locate potential breeding partners.22

Olfactory communication between stabled stallions and mares that are expected to breed can be enhanced by personnel delivering samples of both urine and feces from the stallion to the mare and vice versa. There are anecdotal reports that this practice reduces injuries when partners are brought together for mating.

Marking strategies

Marking, especially with feces, enables horses to communicate their presence and status and to be able to know the whereabouts of other groups of horses. Because rank may dictate the order in which bachelors eliminate onto one another’s excrement, the highest-ranking member of the group may try to ensure that his scent, be it from rolling (see Ch.10), urine or feces, prevails. Regular marking by the natal band stallion is an effective means of avoiding fighting and confrontation between neighboring stallions. The significance of stallion piles lies in their utility as sources of both visual and olfactory signals. They do not occur only at the periphery of a stallion’s range but rather are throughout the area he patrols. This makes sense given their role in inter-stallion displays, which are by no means limited to home-range boundaries.

Donkey communication

Donkeys have a more limited repertoire of vocalizations than horses. Five types of vocalizations have been described: grunts, growls, snorts, whuffles and brays.23 While many calls are similar to those of horses, the most obviously different is the bray. Brays can carry over several kilometers and as a result they allow donkeys to stay in touch across sparsely populated areas. Braying choruses are a feature of social communication, but donkeys other than harem leaders usually reserve braying for attracting other donkeys when isolated, anticipating food or searching for a mate (Jane French, personal communication 2001).

In the free-ranging state, breeding donkey stallions bray most often. Unless part of a braying chorus, subordinate males rarely bray in the presence of higher-ranking males. The bray is used to affirm the stallion’s status and advertise the group’s presence in and possession of the area. Free-ranging jennies and foals usually bray only in response to the braying of a stray group male or when separated from the group. In domestic conditions, they often bray in response to other brays, when expecting food, or when they or their companions are in estrus (see Chs 11 and 12). When braying, the donkey’s message is qualified by the position of its ears. During greeting rituals, usually prior to tactile contact, the ears are held back slightly. While they are flattened further back during agonistic challenges, the ears point forwards during courtship.

Summary of Key Points

• Because horses have excellent vision, the nuances of equine body language can be very subtle.

• Ear position and head posture are the most important variables in non-vocal communication.

• Tail positions can help to coordinate the movements of a group of horses.

• The olfactory cues in urine and the visual stimuli offered by characteristic estrous urination are used by mares to communicate their readiness to mate.

• Dung-piles and the rituals attached to them are effective means of avoiding aggressive interactions between stallions.

References

1. van Dierendonck MC, Bandi N, Batdorj D, et al. Behavioral observations of re-introduced Takhi or Przewalski horses in Mongolia. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1996;50:95–114.

2. Waring GH. Horse behavior: the behavioral traits and adaptations of domestic and wild horses including ponies. Park Ridge, NJ: Noyes, 1983.

3. McDonnell SM, Haviland JCS. Agonistic ethogram of the equid bachelor band. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1995;43:147–188.

4. Waring GH, Dark GS. Expressive movements of horses. Paper presented at Animal Behavior Society Annual Meeting, University of Washington, Seattle, 1978.

5. McGreevy PD, Harman A, McLean AN, Hawson LA. Over-flexing the horse’s neck: a modern equestrian obsession? JVet Behav. 2010;5:180–186.

6. Hawson LA, McLean AN, McGreevy PD. Variability of scores in the 2008 Olympics dressage competition and implications for horse training and welfare. J Vet Behav. 2010;5:170–176.

7. Kiley-Worthington M. The behavior of horses in relation to management and training. London: JA Allen, 1987. 265

8. Houpt KA. Equine welfare. In recent advances in companion animal behavior problems. Ithaca, NY: International Veterinary Information Services; 2001. A0810. 1201

9. Ödberg FO. An interpretation of pawing by the horse (Equus caballus Linnaeus), displacement activity and original functions. Säugetierk Mitt. 1973;21:1–12.

10. McGreevy PD. Why does my horse …? London: Souvenir Press, 1996.

11. Tyler SJ. The behavior and social organisation of New Forest ponies. Anim Behav Monogr. 1972;5:85–196.

12. Proops L, McComb K, Reby D. Cross-modal individual recognition in domestic horses (Equus caballus). Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106(3):947–951.

13. Ödberg FO. Bijdrage tot de studie der gedragingen van het paard (Equus caballus Linnaeus). Thesis, State University Ghent, Belgium, 1969.

14. Munaretto KR. Reciprocal voice recognition from auditory cues by a mare and her foal (Equus caballus). Unpublished Research Report, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, 1980. Cited in reference 2.

15. McGreevy PD, Cripps PJ, French NP, Green LE, Nicol CJ. Management factors associated with stereotypic and redirected behavior in the Thoroughbred horse. Equine Vet J. 1995;27:86–91.

16. Krueger K, Flauger B. Olfactory recognition of individual competitors by means of faeces in horse (Equus caballus). Anim Cogn. 2011;14:245–257.

17. Hothersall B, Harris P, Sörtoft L, Nicol CJ. Discrimination between conspecific odour samples in the horse (Equus caballus). Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2010;126:37–44.

18. Lindsay FEF, Burton FL. Observational study of ‘urine testing’ in the horse and donkey stallion. Equine Vet J. 1983;15:330–336.

19. Marinier SL, Alexander AJ, Waring GH. Flehmen behavior in the domestic horse: discrimination of conspecific odours. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1988;19:227–237.

20. Stahlbaum CC, Houpt KA. The role of the flehmen response in the behavioral repertoire of the stallion. Physiol Behav. 1989;45:1207–1214.

21. Feist JD, McCullough DR. Behavior patterns and communication in feral horses. Z Tierpsychol. 1976;41:337–371.

22. Kimura R. Volatile substances in feces, of feral urine and urine-marked feces horses. Can J Anim Sci. 2001;81(3):411–420.

23. Moehlman PD. Feral asses (Equus africanus): intraspecific variation in social organization in arid and mesic habitats. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1998;60(2–3):171–195.