CHAPTER 48 Elbow

SKIN AND SOFT TISSUE

SKIN

Cutaneous vascular supply

The skin overlying the cubital fossa receives its blood supply on its anterolateral side by small perforating vessels from the radial collateral artery, together with some small musculocutaneous perforators from the radial recurrent artery which traverse brachioradialis (Fig. 45.4). On the anteromedial side, skin is supplied by small branches from the anastomosis between the inferior ulnar collateral artery and the anterior ulnar recurrent artery and by small branches from the brachial artery.

A plexus of anastomosing vessels covers the posterior aspect of the elbow region. On the medial side, the plexus is supplied by small branches from the superior and inferior ulnar collateral arteries and the posterior ulnar recurrent artery, and on the lateral side from the middle collateral artery and the posterior interosseous recurrent artery.

Cutaneous innervation

The skin of the cubital fossa and the epicondylar regions is innervated by the medial and lateral cutaneous nerves of the forearm (Fig. 45.15). A small proximal area on the lateral aspect is supplied by the distal part of the lower lateral cutaneous nerve of the arm. The skin over the olecranon region is innervated by the distal branches of the posterior cutaneous nerve of the arm, together with proximal branches of the posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm.

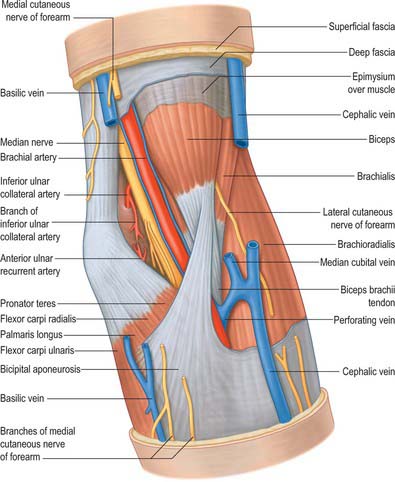

SOFT TISSUE: CUBITAL FOSSA

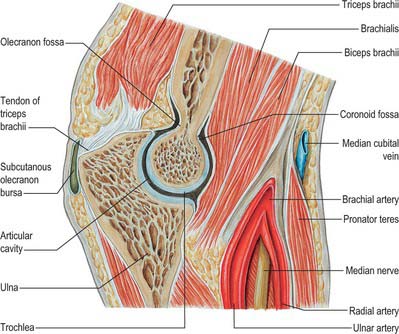

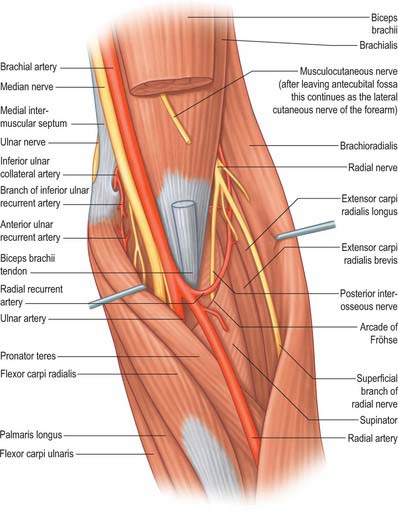

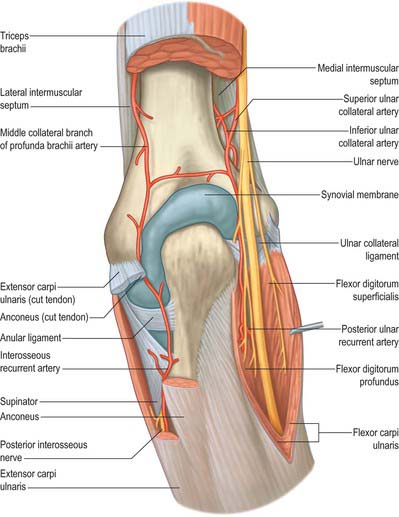

The cubital fossa forms a triangular depression in the middle of the upper part of the anterior aspect of the forearm (Fig. 48.1). The superior border of the fossa is an imaginary line, which joins the two epicondyles of the humerus. The fleshy elevation which constitutes its medial border is formed by the lateral margin of pronator teres and the elevation which forms the lateral border is the medial edge of brachioradialis. The roof of the fossa is formed by the deep fascia of the forearm, reinforced by the bicipital aponeurosis on the medial aspect. The median cubital vein lies on this deep fascia crossed superficially (or sometimes deeply) by the medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm. Brachialis and supinator form the floor of the fossa.

Fig. 48.1 Anterior aspect of the left elbow, superficial structures. The subcutaneous veins have been cut to reveal the subfascial structures. Compare with Fig. 48.6.

From medial to lateral, the fossa contains the median nerve, the terminal part of the brachial artery together with the start of the radial and ulnar arteries and accompanying veins, the tendon of biceps and the radial nerve just under cover of brachioradialis.

JOINTS

The humerus articulates with both the radius and the ulna at the elbow joint. The radius and ulna articulate by synovial superior (proximal) and inferior (distal) radio-ulnar joints and by an intermediate interosseous membrane and ligament, which constitute a fibrous middle radio-ulnar union.

ELBOW JOINT

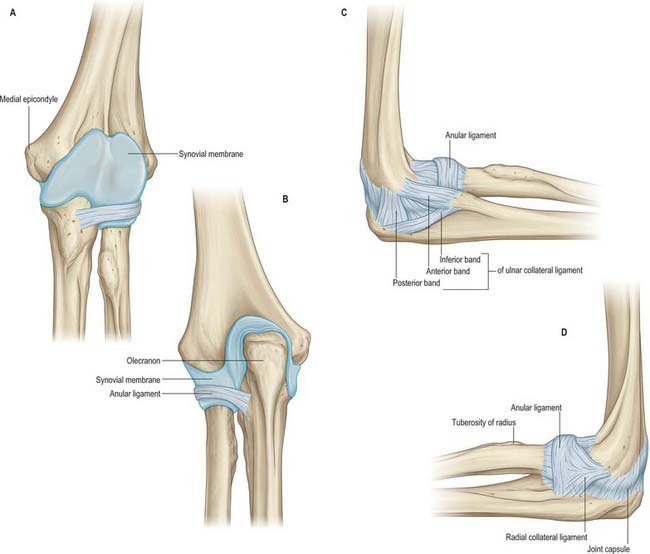

The elbow joint is a synovial joint. Its complexity is increased by continuity with the superior radio-ulnar joint. It includes two articulations (Fig. 48.2). These are the humero-ulnar, between the trochlea of the humerus and the ulnar trochlear notch, and the humero-radial, between the capitulum of the humerus and the radial head.

Fig. 48.2 A–D, The left elbow joint. A, Synovial cavity partially distended: anterior aspect. The fibrous capsule of the elbow joint has been removed but the thick part of the anular ligament has been left in situ. Note that the synovial membrane (blue) descends below the lower border of the anular ligament. B, Synovial cavity partially distended: posterior aspect of the specimen represented in A. In A and B a small part of the ulnar (medial) collateral ligament may be seen. C, Medial aspect. D, Lateral aspect.

The articular surfaces are the humeral trochlea and capitulum, and the ulnar trochlear notch and radial head. The trochlea is not a simple pulley because its medial flange exceeds its lateral, thus projecting to a lower level. This means that the plane of the joint, approximately 2 cm distal to the inter-epicondylar line, is tilted inferomedially; the trochlea is also widest posteriorly where its lateral edge is sharp. The trochlear notch is not wholly congruent with it: in full extension the medial part of its upper half is not in contact with the trochlea and a corresponding lateral strip loses contact in flexion. The trochlea has an asymmetrical sellar surface, largely concave transversely, convex anteroposteriorly: sections show that these profiles are compounded spirals. Swing is therefore accompanied (as in all hinge joints) by screwing and conjunct rotation. The olecranon and coronoid parts of the trochlear notch are usually separated by a rough strip, devoid of articular cartilage and covered by fibroadipose tissue and synovial membrane. The capitulum and the radial head are reciprocally curved; closest contact occurs in midpronation with a semiflexed radius. The rim of the head, which is more prominent medially, fits the groove between humeral capitulum and trochlea.

The humero-ulnar and humero-radial articulations form a largely uniaxial joint which is one of the most congruent, and therefore most stable, joints in the body. The static soft tissue stability of the joint is derived from the anterior capsule and lunar and radial collateral ligaments.

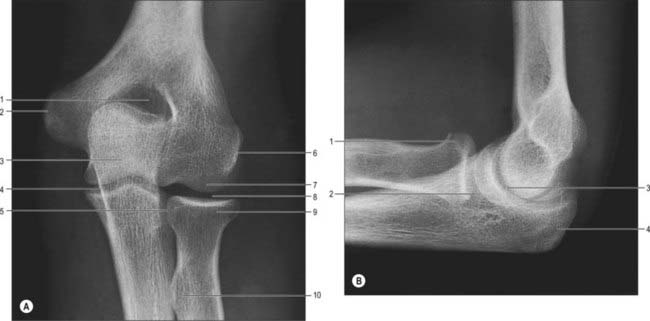

The fibrous capsule (Fig. 48.2, Fig. 48.3, 48.4) is broad and thin anteriorly. It is attached proximally to the front of the medial epicondyle and humerus above the coronoid and radial fossae, and distally to the edge of the ulnar coronoid process and anular ligament, and is continuous at its sides with the ulnar and radial collateral ligaments. Anteriorly it receives numerous fibres from brachialis. Posteriorly the capsule is thin and attached to the humerus behind its capitulum and near its lateral trochlear margin, to all but the lower part of the edge of the olecranon fossa, and to the back of the medial epicondyle. Inferomedially it reaches the superior and lateral margins of the olecranon and is laterally continuous with the superior radio-ulnar capsule deep to the anular ligament. It is related posteriorly to the tendon of triceps and to anconeus.

Fig. 48.3 Radiographs of the left elbow joint of an adult. A, Anteroposterior view: 1. Olecranon fossa. 2. Medial humeral epicondyle. 3. Shadow of olecranon superimposed on trochlea. 4. Humero-ulnar joint. 5. Radial head articulating with radial notch of ulna. 6. Lateral humeral epicondyle. 7. Capitulum. 8. Humero-radial joint. 9. Head of radius. 10. Radial tuberosity. B, Lateral view: 1. Head of radius. 2. Profile of capitulum. 3. Profile of trochlea. 4. Olecranon.

The humero-ulnar and humeroradial articulations have ulnar and radial collateral ligaments.

This is a triangular band, consisting of thick anterior, posterior and inferior parts united by a thin region (Fig. 48.2C). The strongest and stiffest anterior part is attached by its apex to the front of the medial epicondyle and by its broad distal base to a proximal tubercle on the medial coronoid margin. The posterior part, also triangular, is attached low on the back of the medial epicondyle and to the medial margin of the olecranon. Between these two bands intermediate fibres descend from the medial epicondyle to an inferior, oblique band, often weak, between the olecranon and coronoid processes. This converts a depression on the medial margin of the trochlear notch into a foramen, through which the intracapsular fat pad is continuous with extracapsular fat medial to the joint. The anterior band is taut throughout most of the range of flexion, while the posterior band becomes taut between half and full flexion.

The ulnar collateral ligament is related to triceps, flexor carpi ulnaris and the ulnar nerve. Along it, anteriorly, the attachment of flexor digitorum superficialis extends from the medial epicondyle to the medial coronoid border.

This is attached low on the lateral epicondyle and to the anular ligament (Fig. 48.2D). Some of its posterior fibres cross the ligament to the proximal end of the supinator crest of the ulna. It intimately blends with attachments of supinator and extensor carpi radialis brevis. It is taut throughout most of the range of flexion.

The synovial membrane (Figs 48.2-48.4) extends from the humeral articular margins, lines the coronoid, radial and olecranon fossae, the flat medial trochlear surface, the deep surface of the capsule and the lower part of the anular ligament. Projecting between the radius and ulna from behind is a crescentic synovial fold, which partly divides the joint into humero-radial and humero-ulnar parts. Irregularly triangular, it contains extrasynovial fat (Fig. 48.5). Between the capsule and synovial membrane are three other pads of fat: the largest, at the olecranon fossa, is pressed into the fossa by triceps during flexion; the other two, at the coronoid and radial fossae, are pressed in by brachialis during extension. They are all slightly displaced in contrary movements. Smaller synovial-covered tags of fat project into the joint near constrictions flanking the trochlear notch, and cover small non-articular areas of bone.

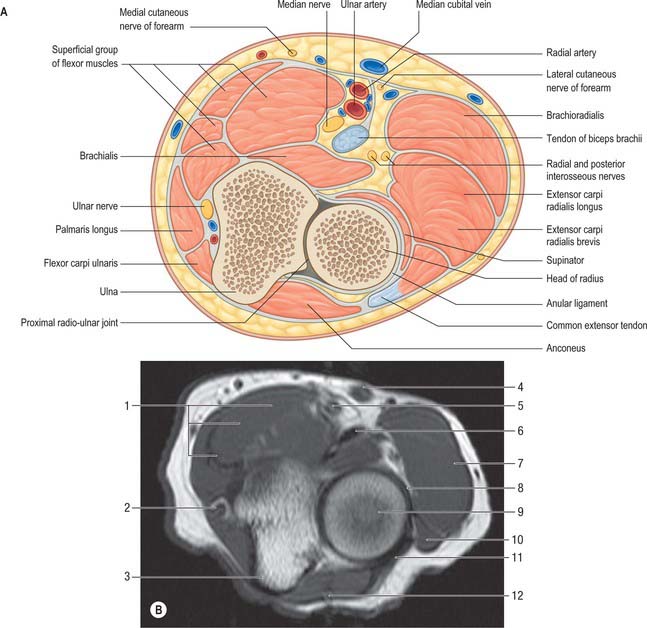

Fig. 48.5 The proximal left radio-ulnar joint. A, Transverse section. B, Axial MRI scan: 1. Superficial group of flexor muscles. 2. Ulnar nerve. 3. Ulna. 4. Median cubital vein. 5. Brachial artery and median nerve. 6. Biceps tendon. 7. Brachioradialis. 8. Anular ligament. 9. Head of radius. 10. Extensor carpi radialis brevis. 11. Common extensor tendon. 12. Anconeus.

A small bursa, the olecranon bursa, lies between the elbow joint capsule and the insertion of triceps tendon. Pressure and friction can lead to inflammation and enlargement of this bursa.

Vascular supply and lymphatic drainage

Articular arteries are derived from the numerous periarticular anastomoses (Fig. 47.6).

Articular nerves are mainly from branches of the musculocutaneous and radial nerves, but the ulnar, median, and sometimes anterior interosseous nerves also contribute. The musculocutaneous branch is from the nerve to brachialis and innervates an anterior part of the capsule; branches of the radial supply posterior and anterolateral regions and come from the nerve to anconeus and the ulnar collateral branch to the medial head of triceps. The ulnar nerve supplies the ulnar collateral ligament behind the medial epicondyle. These articular nerves accompany blood vessels supplying the synovial membrane, fat pads and epiphyses; they presumably contain vasomotor fibres as well as afferent fibres serving pain and proprioception.

Being a uniaxial joint, the elbow allows flexion and extension, the ulna moving on the trochlea, and the radial head on the capitulum. However, ulnar flexion–extension is not a pure swing but is accompanied by slight conjunct rotation, the ulna being slightly pronated in extension, supinated in flexion. Since the capitulum is smaller than the radial facet, the head of the radius can be felt at the back of the joint in full extension, which is limited by tension in the capsule and muscles anterior to the joint (extension being the close-packed position) and the entry of the tip of the olecranon into the olecranon fossa. Flexion is limited chiefly by apposition of soft parts: in full flexion the rim of the radial head and the tip of the ulnar coronoid process enter the radial and coronoid fossae of the humerus respectively.

When the forearm is fully extended and supinated, it diverges laterally forming with the upper arm a ‘carrying angle’ of approximately 163°; its ulnar border cannot contact the lateral surface of the thigh. The ‘carrying angle’ is caused partly by projection of the medial trochlear edge about 6 mm beyond its lateral edge and partly by the obliquity of the superior articular surface of the coronoid, which is not orthogonal to the shaft of the ulna. Tilt of the humeral and ulnar articular surfaces is approximately equal, hence the carrying angle disappears in full flexion, the two bones reaching the same plane. When the adducted arm is flexed the little finger meets the clavicle, because of the position of the resting humerus; when the humerus is rotated laterally, the hand reaches the front of the shoulder. The carrying angle is also masked by pronation of the extended forearm, which brings the upper arm, semipronated forearm and hand into line, increasing manual precision in full extension of the elbow or during extension.

These are limited to slight ulnar screwing, abduction and adduction, and anteroposterior translation of the radial head on the capitulum. In translation the radial head moves on the ulnar radial notch and the anular ligaments are slewed backwards and forwards, more so when the elbow is semiflexed.

Flexion: brachialis, biceps brachii and brachioradialis. In slow flexion or its maintenance against gravity, brachialis and biceps are principally involved, even for light loads. With increasing speed, activity in brachioradialis is increasingly prominent; its attachments determine that it acts most effectively in midpronation. Against resistance, pronator teres and flexor carpi radialis may also act.

Extension: triceps, anconeus and gravity. In rapid extension, brachioradialis may be active.

PROXIMAL (SUPERIOR) RADIO-ULNAR JOINT

The proximal radio-ulnar joint is a uniaxial pivot joint.

The articulating surfaces are between the circumference of the radial head and the fibro-osseous ring made by the ulnar radial notch and anular ligament.

The proximal radio-ulnar joint has anular and quadrate ligaments.

This is a strong band, which encircles the radial head, holding it against the radial notch of the ulna. Forming about four-fifths of the ring, it is attached to the anterior margin of the notch, broadens posteriorly and may divide into several bands. It is attached to a rough ridge at or behind the posterior margin of the notch; diverging bands may also reach the lateral margin of the trochlear notch above and proximal end of the supinator crest below. The proximal anular border blends with the elbow joint capsule, except posteriorly where the capsule passes deep to the ligament to reach the posterior and inferior margins of the radial notch. From the distal anular border a few fibres pass over reflected synovial membrane to attach loosely on the radial neck. The external surface of the anular ligament blends with the radial collateral ligament and provides an attachment for part of supinator. Posterior to it are anconeus and the interosseous recurrent artery. Internally the ligament is thinly covered by cartilage where it is in contact with the radial head; distally it is covered by synovial membrane, reflected up onto the radial neck.

The synovial membrane is continuous with that of the elbow joint so that the proximal radio-ulnar joint and elbow joint form one continuous synovial cavity. It is attached to the articular margins and lines the capsule and anular ligament. It is prevented from herniation between the anterior and posterior free edges of the anular ligament by the quadrate ligament.

Articular arteries are derived from the numerous periarticular anastomoses (Fig. 47.6).

The prime stabilizing factor (Fig. 48.2, Fig. 48.3) is the anular ligament which encircles the radial head and holds it against the radial notch of the ulna.

Movements and muscles producing movement

See the description of the distal radio-ulnar joint (p. 468).

Injuries around the elbow

Posterior dislocation of the elbow joint with ulnar abduction can be complicated by fracture of the coronoid process as it impinges against the trochlea of the humerus. The normal triangular relationship between the olecranon and the two humeral epicondyles is disrupted. The brachial artery and/or median and ulnar nerves can occasionally be damaged in these injuries. The strength of the collateral ligaments is such that the medial epicondyle is frequently torn off in lateral dislocations.

Subluxation of the radial head through the anular ligament arising from a sudden jerk on the arm is a relatively common injury in young children (known as ‘pulled elbow’). This is because the anular ligament has vertical sides in children compared with more funnel-shaped sides in adults. Reduction involves forcefully supinating and flexing the elbow which snaps the ligament back into place.

Supracondylar distal humeral fractures are usually seen in children following a fall on the outstretched hand. The distal fragment in usually displaced posteriorly. The jagged end of the proximal fragment can sometimes injure the brachial artery or the median nerve.

DISTAL (INFERIOR) RADIO-ULNAR JOINT

Movements at the radio-ulnar joint complex pronate and supinate the hand. The distal radio-ulnar joint and the movements which occur during supination and pronation are described on page 468.

VASCULAR SUPPLY AND LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE

ARTERIES

Brachial artery

The brachial artery is central and divides near the neck of the radius into its terminal branches, namely the radial and ulnar arteries (Fig. 48.1, Fig. 48.6). The skin, superficial fascia and median cubital vein are anterior, separated by the bicipital aponeurosis. Posteriorly, brachialis separates it from the elbow joint. The median nerve is medial proximally but is separated from the ulnar artery by the ulnar head of pronator teres. Lateral are the tendon of biceps and the radial nerve, the latter concealed between supinator and brachioradialis.

Radial artery

The radial artery passes deep to brachioradialis and gives off the radial recurrent artery before continuing into the forearm (Fig. 48.1, Fig. 48.6).

The radial recurrent artery (Fig. 47.6, Fig. 48.6) arises just distal to the elbow, passing between superficial and deep branches of the radial nerve to ascend behind brachioradialis, anterior to supinator and brachialis. It supplies these muscles and the elbow joint, anastomosing with the radial collateral branch of the profunda brachii.

Ulnar artery

The ulnar artery gives off the anterior and then the posterior ulnar recurrent arteries before passing deep to pronator teres to continue its course in the forearm (Fig. 48.1, Fig. 48.6). In the forearm, the posterior interosseous artery (a branch of the ulnar artery via the common interosseous artery), gives rise to the posterior interosseous recurrent artery which passes proximally to supply the elbow region.

The common interosseous, anterior interosseous and posterior interosseous arteries, and muscular branches of the ulnar artery, are described on p. 852.

Anterior ulnar recurrent artery

The anterior ulnar recurrent artery (Fig. 47.6) arises just distal to the elbow, ascends between brachialis and pronator teres, supplies them and anastomoses with the inferior ulnar collateral artery anterior to the medial epicondyle.

Posterior ulnar recurrent artery

The posterior ulnar recurrent artery (Fig. 47.6) arises distal to the anterior ulnar recurrent, and passes dorsomedially between flexors digitorum profundus and superficialis, ascending behind the medial epicondyle; between this and the olecranon, it is deep to flexor carpi ulnaris, ascending between its heads with the ulnar nerve. It supplies adjacent muscles, nerve, bone and elbow joint, and anastomoses with the ulnar collateral and interosseous recurrent arteries (Fig. 47.6).

Posterior interosseous recurrent artery

The posterior interosseous recurrent artery is a branch of the posterior interosseous artery. It passes proximally through supinator to lie deep to anconeous posterior to the lateral epicondyle. It gives off branches which take part in the anastomotic cutaneous plexus around the olecranon.

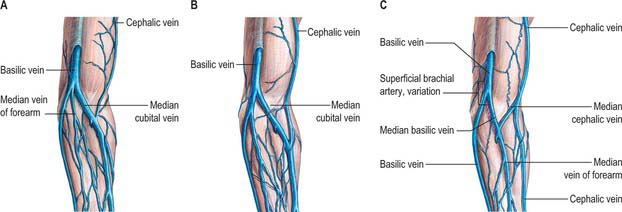

VEINS

The deep and superficial veins supplying the elbow and related structures are described on page 853. Fig. 48.7 shows the common variants of the superficial veins of the cubital fossa: their easy access means that the cubital veins are common sites for venous blood puncture and intravenous fluid and drug administration.

LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE: SUPRATROCHLEAR NODES

One or two supratrochlear nodes (Fig. 45.6) are superficial to the deep fascia proximal to the medial epicondyle and medial to the basilic vein; their efferents accompany the vein to join the deep lymph vessels.

Small isolated nodes sometimes occur along the radial, ulnar and interosseous vessels, in the cubital fossa near the bifurcation of the brachial artery, or in the arm medial to the brachial vessels.

INNERVATION

Median nerve

In the cubital fossa the median nerve lies medial to the brachial artery, deep to the bicipital aponeurosis and anterior to brachialis (Fig. 48.1, Fig. 48.6).

This is an uncommon entrapment neuropathy of the median nerve occurring in the elbow region. Entrapment can occur typically at four sites. The first occurs at the site of the ligament of Struthers. This ligament represents an anatomical variant and when present connects a small supracondylar spur of bone to an accessory origin of pronator teres. The median nerve can be compressed as it passes under this ligament. The nerve may also be trapped as it passes deep to the bicipital aponeurosis; the aponeurotic edge of the deep head of pronator teres muscle; or the tendinous aponeurotic arch forming the proximal free edge of the radial attachment of flexor digitorum superficialis.

The syndrome presents with pain on the volar aspect of the distal arm and proximal forearm. The symptoms may be aggravated by flexing the elbow against resistance, pronating the forearm against resistance, or flexion of superficialis to the middle finger against resistance, depending on the precise cause of the entrapment. If the anterior interosseous nerve is also compressed there is weakness of all the muscles innervated by the median nerve, including abductor pollicis brevis and the long finger flexors, and sensory impairment on the palm of the hand. Treatment involves exploration of the nerve and surgical decompression.

Musculocutaneous nerve

In the cubital fossa the musculocutaneous nerve lies at the lateral margin of the biceps tendon where it continues on as the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm.

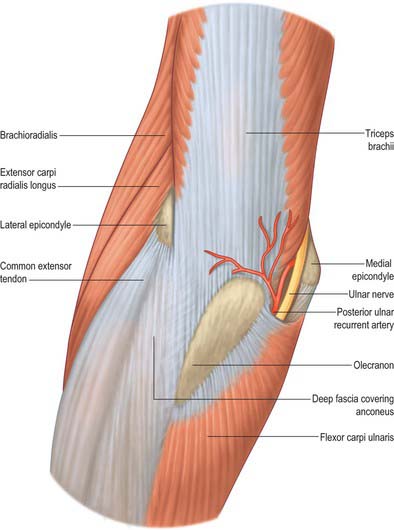

Ulnar nerve

At the elbow the ulnar nerve is in a groove on the dorsum of the medial epicondyle. It enters the forearm between the two heads of flexor carpi ulnaris superficial to the posterior and oblique parts of the ulnar collateral ligament (Fig. 48.6, Fig. 48.8, Fig. 48.9).

Articular branches to the elbow joint arise from the ulnar nerve between the medial epicondyle and olecranon.

Typically the ulnar nerve can be compressed in the tunnel formed by the tendinous arch connecting the two heads of flexor carpi ulnaris at their humeral and ulnar attachments. Other local causes of compression and neuritis at this site include trauma, inflammatory arthritis, compression by the medial head of the triceps, osteophytes, recurrent subluxation of the nerve across the medial epicondyle of the humerus and abnormal muscular variants such as the anconeus epitrochlearis.

The symptoms are pain at the medial aspect of the proximal forearm together with paraesthesia and numbness of the little finger and ulnar half of the ring finger and the ulnar side of the dorsum of the hand. These symptoms are typically worse on forced elbow flexion. There may also be associated weakness of the muscles of the forearm and the intrinsic muscles of the hand innervated by the ulnar nerve. Interestingly, flexor carpi ulnaris and profundus to the ring and little fingers are frequently spared, presumably because the fascicles supplying these muscles are located on the deep aspect of the nerve. Clawing of the hand is therefore unusual in this syndrome.

Surgical treatment involves decompression of the tunnel by division of the aponeurosis of flexor carpi ulnaris with or without subsequent anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve.

Ulnar nerve division at the elbow

– The ulnar nerve is in a vulnerable position as it lies between the medial epicondyle and the olecranon: it lies on bone covered only by a thin layer of skin. It is easily damaged if the ulnar groove is shallow and the nerve may become more prominent than the medial epicondyle or the olecranon when the elbow is fully flexed.

Division of the nerve at the elbow paralyses flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor digitorum profundus to the ring and little fingers and all the intrinsic muscles of the hand (apart from the radial two lumbricals). The clawing of the hand is less intense than occurs after division of the ulnar nerve at the wrist, reflecting the imbalance in action between the long flexors and extensors to the ring and little fingers when finger flexion is produced only by superficialis. In addition there is sensory loss over the little finger and the ulnar half of the ring finger.

Radial nerve

The radial nerve at the elbow lies deep in a groove between brachialis and brachioradialis proximally and extensor carpi radialis distally. It divides into the superficial terminal branch and the posterior interosseous nerve just anterior to the lateral epicondyle (Fig. 48.6).