Chapter Two Research planning

Introduction

Before the actual collection of information or data begins, researchers generally invest considerable time and effort in the planning of their investigations. The first step is to select and to justify the research problem. The second step is to transform the problem into clear researchable aims and research questions and, in the case of quantitative research, hypotheses are also usually specified. Research planning includes the selection of an appropriate research strategy for providing the required evidence to answer the research question. The selection of the appropriate research strategy may depend not only on the research questions being asked, but also on ethical issues and resource constraints that may define the scope and form of the investigation.

Sources of research questions

Advances in health research depend on the identification of questions and problems that promote the development of more powerful theories of health, illness and disability, and then devising more effective ways of assessing, treating and preventing health problems. This advancement depends very much on researchers asking the ‘right’ questions and identifying solvable problems and then applying sound investigation methods to these questions and problems.

The formulation of research questions depends on the expertise of researchers who have a combination of theoretical knowledge and practical experience for identifying problems and asking the right questions. The professional background of researchers is an important consideration, as one’s educational background and practices will influence what are seen as theoretically and professionally interesting problems.

The formulation of even apparently simple research questions is often the culmination of intensive preliminary observations, spending long hours in the library reading through and critically analysing related research, discussing the issues and thinking through a range of issues.

The health care setting in which the researcher works may also have a strong influence on the formulation of research questions. For example, it is an important consideration if the researcher works in a laboratory, a hospital, a community clinic or in private practice. These settings will often influence how the patients’ problems are perceived, and how researchers define professionally relevant solutions to these problems.

In many areas of health care, including areas such as rehabilitation, community health and neurosciences, researchers sharing similar interests may join together in multidisciplinary research teams. Because of the broad range of expertise and perspectives, such teams may be in a position to formulate interesting research questions that can be simultaneously addressed from these different perspectives.

The formulation of research questions

The formulation of research questions is a creative act. It draws upon consideration of previous relevant work in the area under study. This work may be reviewed and the review may give rise to questions that have not been answered by previous work. A literature review is the usual way in which knowledge gaps are identified. The purpose of the review is to answer the questions ‘What do we know?’ and ‘What do we not know?’

Inspiration for research questions often stems from personal experience. Exposure to an issue or problems may raise questions suitable for a research study. Most health practitioners constantly pose questions like ‘What is the best and most effective method of treating this condition?’ and ‘How can we ensure that patients or clients get what they want from this service?’

The justification of research questions

When researchers call on public funds to conduct their studies, they must explain in what way their intended study will contribute to scientific knowledge and/or clinical practice. In ‘pure’ or ‘basic’ scientific research, a proposed investigation is justified in terms of its potential contribution to existing knowledge. In the context of ‘applied’ health research, the investigator may be required to demonstrate that the research will in some way contribute to the improved practice of health care, and benefit patients.

Before embarking on the design and conduct of a research project, the investigator must review previous work and publications relevant to the aims of the intended project. This process is essential, both for providing the appropriate background and context for the investigation, and for justifying the investigation in contributing to existing knowledge. It is a waste of money to duplicate very similar research (although deliberate replication of previous studies may be a legitimate activity if there are uncertainties about the validity of a previous study).

Literature searching may be carried out at appropriate research centres or libraries where scientific and professional journals are stored and, of course, by using the Internet. There are powerful web-based search methods that can simplify the search. The most widely used search tool for health research publications is probably PubMed, the web-based Public Medline (see http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/). Professional library staff can help you to locate the relevant literature. However, the critical evaluation of the literature depends on the application of research methods for the identification of controversies or ‘gaps’ in the available evidence.

Formulation of research aims

Hypotheses in quantitative research

Quantitative research is normally structured so as to test a research hypothesis. Hypotheses are propositions about relationships between variables or differences between groups that are to be tested. Hypotheses may be concerned with relationships between observations or variables (for example, ‘Is there an association between level of exercise and annual health care expenditure?’) or differences between groups (for example, ‘Do patients treated under therapy x exhibit greater improvement than those treated under therapy y ?’). A variable is a property that varies, for example the room temperature, the ages of the patients, or their improvement on a clinical measurement scale.

Some quantitative research projects do not have a hypothesis to be tested in any formal sense. For example, if you are assessing the health needs of a local community, there need not be any specific expectation or hypothesis to be tested. The purpose of the research may be simply to describe accurately the characteristics of the study sample and target population. The goal is not to test a specific hypothesis. This does not mean the research is deficient; it just means it has a different objective from other types of quantitative research projects. So hypothesis testing is a characteristic of many, but not all, quantitative projects.

Qualitative research does not usually test hypotheses. It is concerned with understanding the personal meanings and interpretations of people concerning specified issues. However, most qualitative researchers work with specified research aims and questions to guide their investigation.

The formulation of adequate research aims generally involves a process during which the researcher gradually refines a broadly based issue into more specific operationally defined statements. This process must take into account the logical requirements of designs for information and data collection and ethical standards for conducting health research. In addition, the research aims must inform a realistic data collection procedure which can be supported by the resources available for researchers. We will examine these issues in the rest of this chapter.

Research strategies

Research planning also involves the selection or formulation of research strategies. Research strategies are established procedures for designing and executing research. The research strategies that are outlined in this book include experimental and quasi-experimental strategies, single case research, surveys and qualitative research. Before detailed discussion of the differences between these strategies is undertaken in the following sections, it is instructive to compare the basic structures of survey research and experimental research. As we shall see in subsequent sections, these are fundamentally different ways of conducting research.

Survey research strategies

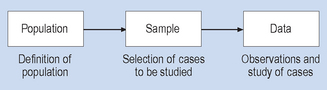

The three essential steps involved in survey research strategies are shown in Figure 2.1. You will note in Figure 2.1 that the researcher defines the population of interest, selects the cases to be studied and then observes or studies them, generating the data. There is no intended active intervention in the situation by the researcher. Indeed, intervention that would change the phenomenon being studied is discouraged and avoided. In this type of research strategy there is a constant tension between the requirements for close and detailed observation (proximity to the phenomenon under study) and the possibility that the behaviour of the research participants under study may change because they are being studied. There are techniques for dealing with this problem, such as the use of unobtrusive measures and participant observation, which will be discussed in subsequent chapters.

Experimental research strategies

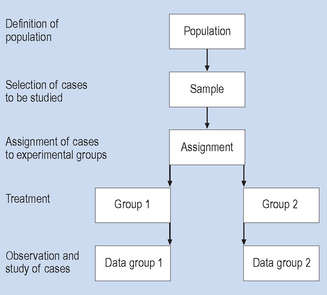

Experimental research strategies involve a sequence of steps, as illustrated in Figure 2.2. As with the survey research strategy, cases are selected for study from a defined population. However, these cases are then assigned (generally by chance or random method) to a treatment (intervention) or non-treatment (non-intervention) group, and then given the intervention or, in clinical contexts, the treatment. The term ‘treatment’ is used here in the sense that the subject or event is being systematically influenced or manipulated by the investigator; that is, in a broader sense than with medical or physical treatment. For this reason the broader term ‘intervention’ is often used in place of the term ‘treatment’. The intervention and non-intervention groups are then observed and compared. If everything went according to plan, any differences in the results for the intervention and non-intervention groups should be a result of the effects of the intervention. This type of design is often called a randomized controlled (sometimes clinical) trial or RCT. In some review systems such as the Cochrane Collaboration system, the RCT is considered to be the ‘best’ level of evidence to establish the effectiveness of an intervention.

Thus, there is quite a difference in the structure of experimental and survey (non-experimental) and qualitative research strategies. Cook & Campbell (1979) proposed a separate class of ‘quasi-experimental’ strategies (which are really just tightly structured non-experimental strategies) that we will also cover later in this book.

The decision of the investigator to adopt specific research strategies depends on the phenomenon being studied and the specific question type of research (causal or descriptive) being investigated.

Research planning: ethical considerations

In health research, where the health and lives of people participating in the study may be at stake, ethical considerations play a key role in research planning and implementation. For instance, consider the question of whether cigarette smoking has negative impacts on health. One way of investigating this question would be through experiments, which are generally considered to be the design best suited to establishing causal relationships. However, it would be ethically unacceptable to have a number of people randomly assigned to a group involved in long-term, heavy cigarette smoking as this would very likely damage their health. Clearly, to meet ethical criteria, evidence must come from studies in which investigators observe the effects of smoking in persons who have themselves chosen to smoke.

A research process is judged to be ethical by the extent to which it conforms to or complies with the set of standards or conventions in the context in which the research is to be carried out. In differ-ent countries, the various medical research councils have developed detailed statements concerning these standards. In the United Kingdom the Medical Research Council has a series of statements and publications available at its web-site (http://www.mrc.ac.uk), as does the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council on its web-site at http://www.nhmrc.gov.au. Canada has the statements by the Interagency Advisory Panel on Research Ethics (http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca). In the United States there is a proliferation of bodies with research ethics guidelines, mostly based upon the 1979 work by the Belmont group. All of these guidelines draw upon the pioneering 1964 Helsinki declaration from the World Medical Association.

Most health services and higher education institutions now have their own ethics committees to oversee health research involving humans and/or animals. Ethics committees, along with the researcher, are responsible for interpreting and enforcing ethical standards. It should be noted, however, that even when a given research proposal is judged to be ethical, it may not be seen as moral by specific individuals or groups in a community. A good example is animal experimentation when the research involves painful or stressful procedures such as surgery. According to the value systems of some persons and groups, such work may be considered to be intrinsically immoral. From this viewpoint, there may be no acceptable justification for inflicting suffering on animals, even when the results may be beneficial for humans. Others may argue that such procedures are morally justified, given that they are necessary for the advancement of the biological and medical sciences and provided that reasonable steps are taken to limit the suffering of the animals. There are no absolute solutions for such controversies as they involve human values, but discussing these issues in public may help to establish a degree of consensus in the community and guidance for the ethical decisions of researchers.

It is beyond the scope of this discussion to examine in full the ethics of health research, but the following issues are central to making decisions in these areas:

A responsible investigator is required to take into consideration ethical principles and to plan research projects accordingly so that no, or the minimum possible, harm is caused. Therefore, the health researcher must use considerable ingenuity in designing valid investigations, while maintaining ethical values. One of the roles of ethics committees is to guide investigators on complex issues, and to ensure that research is conducted in accordance with accepted community principles.

Selection of research strategies: economic considerations

Selection of appropriate research strategies can also be influenced by the resources available to investigators. Some projects involving the evalu-ation of the safety and effectiveness of new drugs, or the identification of risk factors in cardiac disease, have taken tens of millions of dollars to finance. Research planning takes into account economic issues, such as:

The availability of resources strongly influences the scope of the research programme and also the research strategy selected by the investigator. A research project must be shown to be feasible from a cost viewpoint before it is initiated. It is only after the ethical constraints and economic resources have been evaluated that the researchers’ questions can be transformed into clearly defined hypotheses or aims.

It is important when conducting research that the identities of all supporting agencies and individuals are disclosed to the participants in order that their agreement to participate is fully informed.

Steps in research planning

The following steps should be considered in quantitative research before actual data collection begins. The term ‘data’ refers to the set of observations recorded during an investigation.

The above points are written up in the form of a research protocol. This protocol is submitted to supervisors, colleagues or ethical committees, for scrutiny of methodological and ethical problems. It is only when the protocol is acceptable to all these parties that the actual data collection begins. It is often desirable to carry out a small-scale preliminary study, called a ‘pilot’. This is an economical way of identifying and eliminating potential problems in the large-scale investigation.

Summary

The planning of a research project requires the transformation of a vague question or problem into clearly stated aims or questions. To achieve this, the researcher should review the relevant literature and evaluate ethical considerations and economic constraints in conducting the investigation. Next, an appropriate research strategy needs to be selected. On the basis of the above, the researcher is in a position to state precisely the aims or hypotheses being investigated.

Before data collection begins, a protocol for the complete investigation is scrutinized by colleagues to correct methodological problems, or to prevent unethical research.

Self-assessment

Explain the meaning of the following terms: