Chapter 14 Abnormal labour

Spontaneous onset of labour followed by efficient uterine activity and delivery around a time of 8 hours for multiparous and 12–14 hours for primiparous women is accepted as normal. Labour complicated by problems of uterine contractility or integrity (powers), adequacy of the pelvis (passage) and fetal complications (passenger) is considered abnormal.

ABNORMAL UTERINE ACTIVITY

False labour (spurious labour)

Braxton Hicks or practice contractions may be exceptionally uncomfortable or of longer duration, thus giving the impression that labour has started. Repeated episodes of false labour or spurious labour on the other hand can signify fetal compromise and the need for early delivery to avoid fetal death.

Management

Precipitate labour and delivery

Labour resulting in delivery less than 2 hours after onset of uterine contractions is accepted as rapid or precipitate. Dangers include delivery in an unsuitable or non-sterile environment with risk of fetal and maternal trauma. Precipitate labour and delivery are possible in the following conditions:

Management

Sudden cessation of labour

When labour stops suddenly suspect uterine rupture. Uterine rupture is usually, but not always, preceded by evidence of fetal distress and continuous lower abdominal pain.

Management

Box 14.1 gives more information on uterine rupture.

Classification

Rupture may be incomplete (intact peritoneum) or complete (uterine cavity communicates directly with peritoneum cavity). This complication occurs in between 1 in 140 and 1 in 300 labours with a uterine scar.

Associations

PROLONGED LABOUR

Labour is prolonged if it lasts more than 24 hours. This concept is dangerous if it suggests the mistaken connotation that labour can continue for 24 hours before delay is diagnosed. Labour should be considered prolonged once it lags behind the normal partogram by 2–3 hours. This definition draws attention earlier to development of abnormality. Labour is prolonged because of:

Abnormal contractions (powers)

Infrequent weak contractions (hypotonic uterine activity)

Most likely reason is misdiagnosis of labour. It has been said that the overstretched uterus does not labour well but evidence for this is thin.

Frequent strong contractions (hypertonic contractions)

These can follow the inappropriate use of oxytocics. Prolonged labour associated with strong contractions is seen principally in multiparous mothers with disproportion. The practised uterus mounts an increased effort to overcome the obstruction. The resultant frequent strong contractions and increased uterine tone result in both maternal and fetal distress. If allowed to continue tetanic uterine activity can occur. A retraction ring denoting the junction between the strong contracting upper uterine segment and the overstretched lower segment is observed as a late sign of imminent uterine rupture.

Management

Incoordinate uterine activity

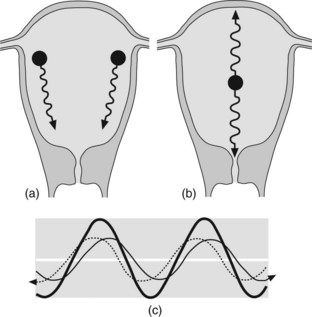

The pacemaker for myometrial activity is normally situated at the cornu of the uterus. When pacemaker activity develops at alternative sites and interrupts fundal dominance, irregular uterine contractions are produced and incoordinate uterine activity results. Incoordinate uterine activity produces poor uterine propulsive effort, increased uterine tone and intermittent painful strong uterine contractions (Figure 14.1). This is usually, but not exclusively a condition of primiparous women in whom an element of disproportion is present. This condition is more likely if the woman is frightened, distressed or anxious as in a first labour, particularly if she is over the age of 35 years.

Figure 14.1 Fundal dominance with (a) normal pacemaker activity and (b) ectopic pacemaker and incoordinated uterine activity. (c) Schematic illustration of ectopic pacemaker activity resulting in high amplitude and attenuated contraction waves of incoordinated activity.

Passenger

Another cause for failure to progress is due to problems with the passenger (fetus/fetuses). There are four main factors:

It is essential to exclude these factors when poor progress presents. Malposition can sometimes be corrected by the use of oxytocin but its injudicious use in the other situations may result in uterine rupture.

The occipitoposterior position (see Chapter 16) is a common cause of slow progress, particularly in primigravid mothers. Frequently this malposition is associated with backache and early membrane rupture. Potential for deflection, hence a larger fetal head diameter, together with need to rotate from a posterior position to a more optimum occipitoanterior position contributes to prolonged labour. Adequate uterine activity is necessary to ensure rotation. In an android pelvis, failure to achieve rotation to occipitoanterior results in arrest at occipitotransverse. This will need assisted rotational delivery if the fetal head is low down and disproportion is excluded. At mid-pelvic level the correct approach is for delivery by caesarean section.

Fetal abnormality includes conjoined twins or tumours, for example, cystic hygromas. In contemporary practice most of these are identified antenatally on ultrasound scanning. In twin labour, consider ‘locking’ when there is failure of descent despite ideal conditions. Caesarean section is usually required. The risk is highest when the first twin is breech.

Fetal abnormality also includes growth restriction. See Box 14.2 for procedures in cases of intrauterine growth restriction.

Box 14.2 Intrauterine growth restriction

Abnormal descent (passage)

Any condition, which hinders descent, will prolong labour. Obstruction to descent is due to the following:

Management

Deficient/delayed cervical dilatation (passage)

Poor cervical dilatation reflects or contributes to the slow progress of labour.

CONSEQUENCES OF PROLONGED LABOUR

Fetus

The consequences for the fetus include trauma, acidosis, hypoxic damage, infection and increased perinatal mortality and morbidity.

Mother

The consequences for the mother are reduced morale, exhaustion, dehydration, acidosis, infection and risk of uterine rupture. The need for surgical intervention increases mortality and morbidity. Ketoacidosis by itself can result in poor uterine activity and prolonged labour.

General management

TRIAL OF LABOUR

All labour can be considered a trial. The term ‘trial of labour’ is reserved for situations where possible complications of labour are anticipated. The trial assesses the adequacy of the pelvis and the ability of the fetus or mother to withstand labour.

Contraindications

Requirements

Failed trial of labour

The trial must be abandoned when:

If the anticipated problem is limited to the pelvic outlet and instrumental delivery is considered, the term trial of forceps or ventouse is used. Delivery is by caesarean section if the trial of labour or trial of instrumental delivery fails. Caesarean section is required for subsequent pregnancies if the fetal size is the same or larger.

TRIAL OF SCAR OR VAGINAL DELIVERY

This term is used when vaginal delivery is considered after a previous lower segment caesarean section, or on occasion, a hysterotomy where the midline incision is sited in the lower half of the uterus.

Contraindications

Requirements

Many obstetricians are loath to allow vaginal delivery after any caesarean section. Caesarean section is not without risk and when conditions are satisfactory vaginal delivery can be safer and provide the woman with an experience of normal childbirth. In less than ideal conditions attempts at vaginal delivery can result in uterine rupture. It is, therefore, important that:

The uterine scar may be weakened after each successive vaginal delivery. Repeated vaginal delivery after previous caesarean section must be conducted with extreme caution.

Adamson SL. Arterial pressure, vascular input impedance, and resistance as determinants of pulsatile blood flow in the umbilical artery. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 1999;84:119-125.

Alfirevic Z, Neilson JP. Doppler ultrasonography in high risk pregnancies: systematic review with meta-analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;172:1379-1387.

CESDI CESDI, 5th Annual Report 1998 Maternal and child health research consortium. London

Chang TC, Robson FC, Spencer JA, et al. Prediction of perinatal morbidity at term in small fetuses: comparison of fetal growth and Doppler ultrasound. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1994;101:422-427.

Divon MY, Ajglund B, Niselo H, et al. Fetal and neonatal mortality in the post term pregnancy: the impact of gestational age and fetal growth restriction. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;178:726-731.

Kiserud T, Eik-Nes SH, Vlaas HG, et al. Ductus venous blood flow velocity and the umbilical circulation in the seriously growth retarded fetus. Ultrasound Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1994;4:109-114.

Phelan JP, Clarke SL, Daiz MA, et al. Vaginal birth after Caesarean. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1987;157:1510-1515.

Piper JM, Xenakis EM, McFarland M, et al. Do growth retarded premature infants have different rates of perinatal morbidity and mortality than appropriately grown premature infants?. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;87:169-174.

Tyson JE, Kennedy K, Broyles S, et al. The small for gestational age infant: accelerated or delayed pulmonary maturation? Increased or decreased survival?. Paediatrics. 1995;95:534-538.