Theory in Research

Think of a particular field of inquiry or a particular research question or query of interest to you, and ask yourself the following two questions:

What do we know about this phenomenon?

What do we know about this phenomenon?

What theories have been developed to explain or understand the phenomenon?

What theories have been developed to explain or understand the phenomenon?

You will want to keep asking these basic questions as you engage in the research process and explore different problems of interest. For each research question or query that you pose, the way in which you answer these basic questions will largely determine the type of research actions (e.g., design strategy, analysis, and reporting) that you will implement. As discussed in previous chapters, the level of knowledge and theory development in a particular field shapes how a research question or query is framed and a design strategy is implemented. Theory has a critical role in both experimental-type and naturalistic research as well as in integrated methodologies.

Why is theory important?

When people hear the word “theory,” they often feel overwhelmed and assume that the term is not relevant to their daily lives or is too abstract and complicated to understand. However, think about how difficult life would be without theory. Theory informs us each day in many aspects of our lives, from knowing how to prepare for the weather to guiding our professional practice. For example, predicting the weather is based on existing theory. The meteorologist looks at present weather conditions and past weather patterns and makes a prediction in the form of a forecast.

In health and human service delivery, you make a decision about which intervention to use with a patient or client on the basis of theory. You use a theory to guide your decisions, even though you may not be fully cognizant that you are actually doing so.

As discussed in Chapter 1, a primary purpose of research is directly linked to theory. In experimental-type designs, one primary purpose of research is to test theory using deductive processes. In naturalistic inquiry, the purpose is usually to generate theory using induction or abduction. This chapter introduces another important aspect in the relationship between research and theory: that is, you must have a theoretical framework to conduct adequate research. This is the primary point of this chapter.

As discussed throughout this text, thinking and action processes are equally important parts of research. Critical to the thinking processes are the set of human ideas that can be organized to understand human experience and phenomena. As described later in this chapter, these ideas are theories or parts of theories. Even though we may not realize it, theory frames how we ask, look at, and answer questions. Theory provides conceptual clarity and the capacity to connect the new knowledge obtained through data collection action processes to the vast body of knowledge to which it is relevant. Without theory, we do not have conceptual direction. Data that are derived without being conceptually embedded in theoretical contexts do not advance our understanding of human experience and ultimately are not useful. Remember, “usefulness” is an important component of our definition of research. Of importance is that theory helps a researcher see the forest instead of just a tree. That is, it helps the researcher make sense of details and place them within a larger context. If we only focus on a single tree or detail, we lose sense of the whole and how that one detail or observation functions or relates to the larger context.

Let us examine more closely why theory must inform or shape research actions by considering the meaning and use of common terms such as “race” and “ethnicity.”

What is theory?

By now you might be asking, “So what is theory?” Definitions range from traditional views of theory as systems to organize, describe, and predict a single reality; to abstract systems of language symbols that provide multiple interpretations and ideas of phenomena; to ideological foundations for social action.3

We draw on Kerlinger's classic definition of theory because we believe it is the most comprehensive and useful for investigators and students of research. Kerlinger defines theory as “a set of interrelated constructs, definitions, and propositions that present a systematic view of phenomena by specifying relations among variables, with the purpose of explaining or predicting phenomena.”4 In this definition, theory is a set of related ideas that has the potential to explain or predict human experience in an orderly fashion, and it is based on data. The theorist develops a structural map of what is observed and experienced in an effort to promote understanding and facilitate the ability to predict outcomes under specific conditions. Through deductive research approaches or empirical investigations, theories are either supported and verified or refuted and falsified. Through inductive approaches, theories are incrementally developed to explain and give order to observations of human experience.

As implied in Kerlinger's definition, four interrelated structural components are subsumed under theory and range in degree, or level, of abstraction. Although numerous taxonomies for the parts of a theory have been proposed,5 we suggest that the four basic structures of theory are concepts, constructs, relationships, and propositions or principles. Let us first examine the meaning of abstraction and then discuss each level.

Levels of Abstraction

Abstraction often conjures up a vision of the ethereal, the “not real.” In this book, however, we use the term “abstraction” as it relates to theory development, to depict a symbolic representation of shared experience. For example, if we all see a form that has fur, a tail, four legs, and barks, we name that observation a “dog.” We have shared in the visual experience and have created a symbol (the word “dog”) to name our sensory experience.

All words are merely symbols to describe and communicate experience. Words are only one form of abstraction; different words represent different levels of abstraction, and a single word can represent multiple levels of abstraction.

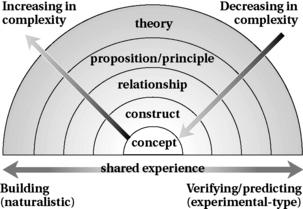

Figure 6-1 displays the four levels of abstraction within theory and their interrelationships. Shared experience is the foundation on which abstraction is built. It is important to recognize that we do not use the term “reality” as the foundation. Reality implies that there is only one viewpoint from which to build the basic elements of a theory. In contrast, this text is based on the premise that humans experience multiple realities and multiple perspectives about the nature of reality. As such, levels of abstraction must be built on shared experience, defined as the consensus of what we obtain through our senses. For experimental-type researchers who work deductively, shared experience is usually thought of as sense data, or that which can be reduced to observation and measurement. For researchers working inductively and abductively in the naturalistic tradition, shared experience may include meanings and interpretations of human experience.

Let us use the example of the “furry being with four legs and a tail that barks” to illustrate the multiple meanings that can be attributed to shared experience. Shared experience tells each of us that this is a dog, but the word “dog” may also carry with it diverse meanings, such as fear or happiness.

Each type of experience is equally important to acknowledge, as are the different meanings attributed to a single word.

Concepts

As depicted in Figure 6-1, a concept is the first level of abstraction and is defined as a single, first-order symbolic representation of an observable or experienced referent.6 By first order, we mean that there is no abstract level between shared experience and concept. Concept is directly inferred from observations and other sense data. Concepts are the basic building blocks of communication because they provide us with the means to tell our experiences and ideas to one another. Without concepts, we would not have language.6 In the case of the “furry being,” the word “dog” can function as a concept. At this basic level of abstraction, the term “dog” describes an observation shared by many. The words “furry,” “tail,” “four legs,” and “bark” are also concepts because they are directly sensed.

In experimental-type research, concepts are selected before a study is started and are defined to permit direct measurement or observation. In naturalistic research, concepts are derived primarily through direct observations and continual engagement with the phenomenon of interest in the context in which it occurs.

Constructs

A construct, the next level of abstraction, does not have an observable or a directly experienced referent in shared experience. Meanings become important to consider at this level of abstraction, because two individuals who articulate the same construct may attribute disparate meanings to it. If we look again at the term dog as a construct rather than a concept, the word may mean “fear” to some and “happiness” to others. Although we stated earlier that dog is a concept, in this case, “dog” functions as a construct because what is observable is not the communicated meaning. Rather, the meaning of the term takes on the feelings evoked by “dog,” such as fear or happiness.

Fear and happiness are also examples of constructs. What may be observed are the behaviors associated with fear or happiness, that is, someone who sweats, shakes, and turns pale at the site of a dog or someone who smiles, approaches, and pets the dog, respectively. These observations of both feelings are synthesized into the constructs of fear and happiness. Thus, fear and happiness are not directly “observed” but are surmised by observations of human behavior and are based on a constellation of behavioral concepts.

Categories provide additional examples of constructs. The category of “mammal” or “canine” is an example of a construct. Although each category or construct is not directly observable, it is composed of a set of concepts that can be observed.

Other examples of constructs relevant to health and human service inquiry include quality of life, health, wellness, life roles, rehabilitation, poverty, illness, disability, functional status, and psychological well-being. Although not directly observable, each is made up of parts or components that can be observed or submitted to measurement. Think about the construct of “quality of life”; which concepts is this construct composed of? Examples of concepts that compose quality of life can include health status, self-efficacy, or positive mood. If you consider that even this relatively low level of abstraction is multifaceted, you can begin to understand why health and human service research is so complex.

Relationships

So far, we have been discussing single-word symbols or units of abstraction. At the next level of abstraction, single units are connected to form a relationship. A relationship is defined as an association of two or more constructs or concepts. For example, we may suggest that the size of a dog is related to the level of fear that a person experiences. This relationship has two constructs, “size” and “fear,” and one concept, “dog.” Think about the construct of “quality of life” and consider the concepts it is composed of and their relationship as it is relevant for a specific population you work with or have an interest in (e.g., elderly, children with mobility impairments, individuals with spinal cord injury, prisoners). For example, research suggests that quality of life in older adults is related to the extent to which functional limitations curtail activity participation. Thus, the relationship between two concepts, disability and activity restriction, is critical to the construct of quality of life as it pertains to older adults living at home.

Propositions (Principles)

A proposition is the next level of abstraction. A proposition, or principle, is a statement that governs a set of relationships and gives them a structure. For example, a proposition suggests that fear of large dogs is caused by negative childhood experiences with large dogs. This proposition describes the structure of two sets of relationships: (1) the relationship between the size of a dog and fear and (2) the relationship between childhood experiences and the size of dogs. It also suggests the direction of the relationship and the influence of each construct on the other. Let's revisit the construct of quality of life. Can you develop a proposition based on the relationship between functional difficulty and activity limitation? One proposition may be that quality of life is affected by the extent to which having a functional difficulty limits participation in valued activities. That is, having a functional difficulty leads to poor quality of life to the extent that activities one wants to participate in are affected or curtailed.

Design Selection and the Four Levels

We conclude our discussion of levels of abstraction with principles that relate these levels to the selection of a particular research design or approach to studying a phenomenon of interest. We view abstraction as the symbolic naming, representation, and frequent communication of shared experience. The further a symbol is removed from shared experience, the higher the level of abstraction. Each level of abstraction moves farther away from shared experience (see Figure 6-1). The higher the level of abstraction, the more complex your design becomes. This principle is based on common sense. If the scope of your study is to examine a construct, a complex investigation may not be necessary, such as that required for the development or testing of a full-fledged theory.

Although concepts, constructs, relationships, and propositions or principles provide the basic language and building blocks of any research project, each research tradition handles the levels of abstraction differently.

Role of theory in design selection

How does theory shape the selection of research design strategies? When theory is well developed and conceptually fits the phenomenon under investigation, deductive studies will likely be implemented, as in the tradition of experimental-type research. When theory is poorly developed or does not fit the phenomenon under study, inductive and abductive studies that generate theory may be more appropriate, as in the tradition of naturalistic inquiry. The degree of knowledge development and relevance of a theory for the particular phenomenon under investigation determines in part the nature and type of research that needs to be conducted.

The relationship of theory and design can be illustrated by considering the classic theory of moral development advanced by Lawrence Kohlberg, a well-known scholar. He suggested three basic levels of moral reasoning that develop and unfold throughout the life span: preconventional, conventional, and postconventional.7 Briefly, in the preconventional reasoning stage, individuals develop notions of right and wrong, based on reward or punishment; in conventional reasoning, individuals use accepted norms of right and wrong to guide their moral decisions; and in postconventional reasoning, humans use their own intrinsic notions of morality to formulate decisions and actions. Many investigators have accepted this theory as truth and have attempted to characterize and predict the moral reasoning of different populations. Scales to measure moral reasoning have been developed on the basis of Kohlberg's theory and have been used with different groups of people representing diverse socioeconomic, age, and gender groups. Based on these studies, populations and individuals have been categorized according to the level of moral reasoning they exhibit. This information has been extremely valuable in promoting our understanding of morality in humans. The characterization of moral reasoning based on Kohlberg's theory is an example of a deductive relationship between theory and research; that is, the theory has been accepted as true, and subsequent studies intend to verify and advance the application of the theory in varied populations.

In most studies of moral reasoning in adults based on Kohlberg's theoretical framework, however, women were reported to reason at a lower level than men. Researchers therefore concluded that women were not as morally advanced as men. Although this conclusion makes no sense, this type of deductive illogic is common practice, particularly when a theory is developed for one group and automatically applied to another without consideration of its “fit.”

Recognizing this illogic with regard to women, researchers using different theoretical frameworks have begun to tackle the issue. For example, researchers using a feminist framework have not accepted Kohlberg's theory as true for women because it is intuitively contrary to what is experienced and believed. These researchers have argued that although knowledge has been well developed in this area, Kohlberg's theory does not seem to fit or to be relevant to the experiences of women. Therefore, investigations of moral reasoning in women as well as for other groups (e.g., individuals from diverse race and ethnic groups) have been developed by applying inductive research strategies. Collectively these studies have shown that women and other groups are not less moral than men but rather base their moral decision making on criteria that were substantially different from those initially identified by Kohlberg's theory and those operationalized in the scales developed to reflect his theory. Thus, research shows that Kohlberg's notions do not explain moral reasoning for a particular group-women. By using inductive strategies, researchers have been able to identify and show the processes by which women and other groups reason and function and thus develop theory that reflects their specific thought processes. Given that Kohlberg developed his theory of moral reasoning by studying white men, the deductive strategy was most valuable in expanding knowledge of the moral reasoning in this group, but not necessarily in women or others from diverse backgrounds. Use of an inductive research strategy illustrates the relationship between theory and naturalistic inquiry; in other words, naturalistic inquiry is extremely valuable as a theory-generating tool, but it also can be used to verify or refute a theory.

Another example more relevant to health and human service practice involves the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF).8 In response to difficulties encountered by experimental-type researchers in applying ICF concepts and classifications to culturally diverse populations and countries, the World Health Organization and National Institutes of Health jointly implemented the Cultural Applicability Research (CAR) study initiative. The purpose of CAR is to develop guidelines for implementing classification schemas and instrumentation across cultural groups. CAR identifies the contextual, multilevel consequences of applying diagnostic conditions and provides empirical knowledge to inform use and interpretation of ICF taxonomy.9

These examples show the limitations of applying theory and knowledge developed on one group to other diverse groups and how this generates both inductive and deductive systematic inquiry in health and human service research.

Now you have a sense of the meaning of theory and how it relates to research knowledge development and the selection of design strategies. Let us now consider the role and relationship of theory and research for each of the specific research traditions.

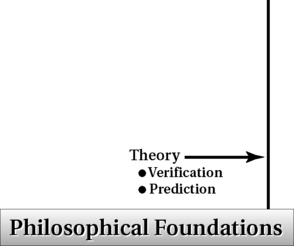

Theory in experimental-type research

Experimental-type researchers begin with a theory and seek to simplify and reduce abstraction by making the abstract observable, measurable, and predictable (see Figure 6-1). This process of theory testing typically involves specifying a theory and then developing testable hunches or hypotheses. A hypothesis is linked to a theory and is a statement about the expected relationships between two or more concepts that can be tested. A hypothesis indicates what is expected to be observed and represents the researcher's “best hunch” as to what may exist or may be found, on the basis of the principles of the theory.

Consider the example of defensive attribution theory. Building on general attribution theory, it has been used as the theoretical foundation in investigations concerning individual and community responses to victims of sexual assault. Defensive attributions are unconscious, self-protective mechanisms10–13; when invoked, they function subconsciously to reduce the observer's fear and threat by attributing character and behavioral blame to the victim. A major hypothesis stemming from this theory is that there is a positive association between perceiving a similarity to the victim and victim blaming.14 That is, the more an individual feels at risk, the more likely she or he is to accept explanations that attribute blame to the victim on the basis of some fault of her own. The hypothesis is based on the theoretical tenet that victim blame identifies the circumstance, which can be avoided and thus can diminish the perceived threat of assault.

On the basis of the development and directionality suggested in underlying theory, hypotheses can be written in two forms, nondirectional or directional (see Chapter 7). The following nondirectional hypothesis can be derived from defensive attribution theory:

A hypothesis can also indicate the direction or nature of a relationship between two concepts or constructs, as in the following example of a directional hypothesis:

Consider yet another example. The Life Span Theory of Control is based on the premise that control over one's immediate life space or personal environment and daily activities is an important human invariant that transcends cultural groups.15 This theory suggests that humans, by their nature, must exert some level of control over behavior-event contingencies in everyday life. Applied to the field of rehabilitation, the theory suggests that persons with physical difficulties resulting in limitations in performing daily activities may be threatened by or experience loss of control. This threat of or actual loss of control may in turn result in feelings of anxiety, which may lead to depression unless strategies, either cognitive or behavioral actions, are implemented to help the person achieve control between behavior and outcomes or a sense of efficacy. By using strategies that enhance control, people experience a sense of enhanced well-being, and positive outcomes are attained.

On the basis of this theory, what do you think are some of the hypotheses that may be generated and tested? One directional hypothesis might be that use of adaptive technology enhances self-efficacy in people who have activity limitations resulting from physical impairments. Now, can you think of other meaningful hypotheses based on this theory?

Consider the hypotheses you thought of and those we suggested. What can you conclude about a hypothesis? As shown in Figure 6-2, a hypothesis is the initial reduction of theory to a more concrete and observable form. On the basis of the hypothesis, the researcher develops an operational definition of a concept so that it can be measured by a scale or other instrumentation. The operational definition of the concept further reduces the abstract to a concrete, observable form. An operational definition of a concept specifies the exact procedures for measuring or observing the phenomenon. In the example of attribution theory, the investigator needs to operationalize identification with the victim and victim blaming. The process of operationalizing a concept is not easy or straightforward. Likewise, in the example of personal control theory, the investigator needs to operationalize self-efficacy and behavioral outcomes. Each researcher may develop his or her own way of operationalizing these key concepts. This process is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 16, in which we examine issues related to measurement and instrument construction and selection.

Using an operational definition, the researcher makes observations that result in data points, which are then analyzed. Analysis determines whether the findings verify, refute, or modify the theory. This is the fundamental premise of the scientific process. Reducing abstraction to measurable components is used primarily to test relationships among concepts of a theory, and it is ultimately used to determine the adequacy of a theory to make predictions and thus control the phenomena under study.

Box 6-1 lists the basic characteristics of the use of theory by experimental-type researchers. The process, referred to as logical deduction, begins with an abstraction and then focuses on discrete parts of phenomena or observations. Constructs are defined and simplified and then operationalized into concepts that can be observed to allow measurement. This process moves from a more abstract to a less abstract level, or to a more concrete and observable level.

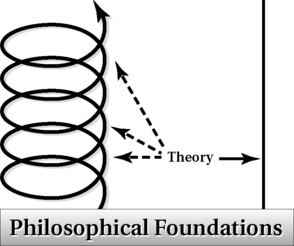

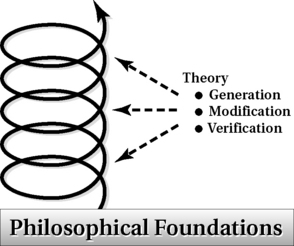

Theory in naturalistic inquiry

Whereas theory testing is the primary goal of researchers in the experimental-type tradition, researchers working in the naturalistic tradition are usually developing or expanding on theory from observations. Thus, in naturalistic inquiry, the researcher begins with shared experience and then represents that experience at increasing levels of abstraction. In this approach, definitions of concepts and constructs are not necessarily set before a study is begun; rather, definitions emerge from the data collection and analytical processes. In many of the orientations of naturalistic research, the aim is to “ground” or link concepts and constructs to each observation or datum. This theory-method link,16 or grounded-theory approach, is described in a classic work by Glaser and Strauss in this way:

Generating a theory from data means that most hypotheses and concepts not only come from the data, but are systematically worked out in relation to the data during the course of the research. Generating a theory involves a process of research.17

As discussed later in this text, each strategy classified as naturalistic inquiry is based on a different set of assumptions about how we come to know human experience. However, all researchers in the naturalistic tradition tend to use qualitative methodologies to ground theory in observations. That is, definitions of concepts and then constructs emerge from the investigative process and analysis of the documentation (the data) of shared experience.16 On the basis of emergent concepts and their relationships, the investigator develops theory to understand, explain, and give meaning to social and behavioral patterns.

Although each design structure describes this process somewhat differently, Figure 6-1 illustrates the basic idea of the inductive process.

In some naturalistic inquiries, theory is used in a similar manner to experimental-type research. Once immersed in observations, the investigator frequently draws on well-established theories to explain these observations and make sense of what is being observed. Consider how the previous discussion of victim blaming might provide the ethnographer with an understanding of cultural views of sexual assault victims. In the process of observing how groups perceive, describe, and respond to sexual assault victims, the ethnographer may be reminded of a defensive attribution theory that seems to fit with the data set. Thus, the theory is applied to the data set as an explanatory mechanism. However, the use of theory in this example occurs after the data have been collected and analyzed. When an investigator is proceeding inductively, theory does not guide data collection and is not imposed on the data; rather, the data may suggest which theory, if any, might be relevant to understanding and explaining observations.

This is not to say that naturalistic inquiry is atheoretical. Theory use, however, has a different function than in experimental-type research. All research begins from a particular theoretical framework based on assumptions of human experience and reality and how we can come to know them. This theoretical framework is not substantive or content-specific, but is structural and process oriented and frames the research approach assumed by the investigator.

Theory can be used in naturalistic inquiry in many ways. One way is that the researcher may begin a study by using a substantive theoretical framework to explore its particular meaning for a specific group of people or in specified situations. For example, an investigator might examine how individuals with disability adapt to their physical changes to achieve control in their environment and the meaning of control for this group. In this case, as in most naturalistic traditions, the function of the substantive theory is to place boundaries on the inquiry rather than fit the data into the theoretical framework by reducing concepts to predefined measures. Alternatively, one or more theories may be used to explain emerging themes or to understand observations. Finally, the purpose of a naturalistic study may be to generate a theory of a particular human behavior or health problem. Theory generation serves primarily to reveal the multiple meanings and subjective understandings of the phenomena under study. In this process of theory construction, knowledge emerges from informants or study participants with concepts and constructs grounded in observations. In the global context, naturalistic research is increasingly used to generate theory about geographies and cultures that have not been studied. Naturalistic theory building ensures that the theory emerges from what is observed rather than being imposed where it may not be accurate.

Box 6-2 summarizes the basic characteristics of the use of theory in naturalistic inquiry. As we illustrate, the treatment of theory occurs primarily within inductive and abductive processes that move from shared experience to higher levels of abstraction.

Table 6-1 presents an overview of the use of theory in both experimental-type and naturalistic research traditions, as well as how theory can be used in an integrated research design.

Summary

In this chapter, we have discussed the following five major points:

1. Theory is fundamental to the research process.

2. Theory consists of four basic components that reflect different levels of abstraction. These levels are concepts, constructs, relationships, and propositions (principles).

3. The level at which a theory is developed and its appropriateness to your phenomenon under study determine in part the nature and structure of research design.

4. Experimental-type research moves from greater to lesser levels of abstraction by reducing theory to specific hypotheses and operationalizing concepts to observe and measure as a way of testing the theory.

5. Naturalistic inquiry moves from less abstraction to more abstraction by grounding or linking theory to each datum that is observed or recorded in the process of conducting research.

References

1. Ahmad, W., Sheldon, T. Race and statistics. In: Hammersley M., ed. Social research: philosophy, politics and practice. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage; 1992:30.

2. Rodriguez, R. Brown: the last discovery of America. New York: Penguin, 2003.

3. Seidman, S. Contested knowledge: social theory in the post-modern era, ed 2. Malden, Mass: Blackwell, 1998.

4. Kerlinger, F.N. Foundations of behavioral research, ed 2. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1973.

5. Mosey, A.C. Applied scientific inquiry in the health professions: an epistemological orientation. Rockville, Md: AOTA, 1992.

6. Wilson, J. Thinking with concepts. Cambridge, Mass: Cambridge University Press, 1966.

7. Kohlberg, L. The psychology of moral development. New York: Harper & Row, 1984;6.

8. International classification of functioning, disability, and health, ed 10, Geneva, World Health Organization, 2004. www.who.int/classifications/icf/en.

9. Ustun, T.B., Catterji, S., Rehm, J., et al. Disability and culture: universalism and diversity. Seattle: Hogrefe & Huber, 2002.

10. Heider, F. The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: Wiley, 1958.

11. Fiske, S.T., Taylor, S.E. Social cognition, ed 2. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1991.

12. Shaver, K.G. Defensive attribution: effects of severity and relevance on the responsibility assigned for an accident. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1970;14:101–113.

13. Thorton, B., Ryckman, R., Robbins, M. The relationship of observer characteristics to beliefs in the causal responsibility of victims of sexual assault. Hum Relations. 1982;35:321–330.

14. Peters, J. Validation of the domestic violence myth acceptance scale. Bangor, University of Maine, 2002. [unpublished Ph.D. dissertation].

15. Schulz, R., Heckhausen, J., O'Brien, A.T. Control and the disablement process in the elderly. Soc Behav Personality. 1994;9:139–152.

16. Patton, M.Q. Qualitative evaluation and research methods, ed 3. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage, 2001.

17. Glaser, B., Strauss, A. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine, 1967.

Assume you are a health or human service professional working in a psychiatric hospital. A new member comes to your group therapy session with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. Theoretically, you know that this diagnosis is associated with a set of symptoms and behaviors, particularly self-degradation, faulty thinking, and melancholia. On the basis of this cognitive-behavioral theoretical understanding of the symptoms, as well as the prediction of the individual's behavioral outcomes, you approach this client with support and engage him or her in a cognitive-behavioral program in which self-degrading ideation is incrementally decreased. Consider the role of theory in your clinical decision making. Without the theory, you would not have known how to work skillfully with this client.

Assume you are a health or human service professional working in a psychiatric hospital. A new member comes to your group therapy session with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. Theoretically, you know that this diagnosis is associated with a set of symptoms and behaviors, particularly self-degradation, faulty thinking, and melancholia. On the basis of this cognitive-behavioral theoretical understanding of the symptoms, as well as the prediction of the individual's behavioral outcomes, you approach this client with support and engage him or her in a cognitive-behavioral program in which self-degrading ideation is incrementally decreased. Consider the role of theory in your clinical decision making. Without the theory, you would not have known how to work skillfully with this client.