Formulating Research Questions and Queries

Research Questions in Experimental-Type Design

Level 1: Questions That Seek to Describe Phenomena

Level 2: Questions That Explore Relationships Among Phenomena

Level 3: Questions That Test Knowledge

Research Queries in Naturalistic Inquiry

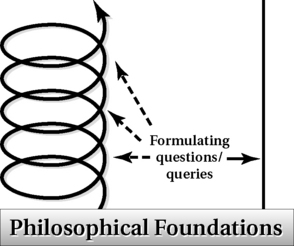

Up to now you have learned about specific thinking and some action processes, such as the role of theory in research (Chapter 6), ways to identify and frame research problems (Chapter 4), and the purpose of and methods for conducting the literature review (Chapter 5). All these processes are part of the important work of refining the structure and content of any type of inquiry. Now you are ready to move beyond these initial starting blocks as we examine how to develop specific questions within the experimental-type tradition and queries within the naturalistic tradition. Developing a question or query represents the first formal point of entry into a study.

We have just used two distinct terms, “question” and “query,” to describe these initial formal points of entry into a study. These terms reflect the different approaches to research used in each tradition. Your research question or query will guide all other subsequent steps and decisions, such as how you collect information and what other types of procedures you will follow.

Research questions in experimental-type design

In experimental-type research, entry into an investigation requires the formulation of a very specific question with a prescribed structure. That is, from a broad topic of interest to you, you must articulate a specific question that will guide the conduct of the investigation. This question must be concise and narrow and must establish the boundaries or limits as to what concepts, individuals, or phenomena will be examined in the study. The question also must be posed a priori, or before engaging in the research process. The question becomes the foundation or basis from which all subsequent research action processes are developed and implemented and on which the rigor of the design is determined.

The purpose of the research question in the experimental-type tradition is to articulate not only the concepts, but also the structure and scope of the concepts that will be studied. The research question leads the investigator to highly specified design and data collection action processes that involve a form of observation or measurement to answer the question. Research questions are developed deductively from the theoretical principles that exist and are presented in the literature.

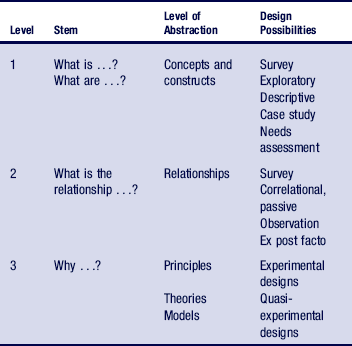

Each type of question reflects a different level of knowledge and theory development concerning the topic of interest. Questions that seek to describe a phenomenon, referred to as Level 1 questions, are asked when little to nothing is empirically known about the topic. Level 2 questions explore relationships among phenomena and are asked when descriptive knowledge is known but relationships are not yet understood. Level 3 questions test existing theory or models and are asked when a substantial body of knowledge is known and well-defined theory is developed.

Level 1: Questions That Seek to Describe Phenomena

Questions that aim to describe phenomena are referred to as Level 1 questions. Level 1 questions are descriptive questions designed to elicit descriptions of a single topic or a single population about which there is theoretical or conceptual material in the literature but little or no empirical knowledge. Level 1 questions lead to exploratory action processes with the intent to describe an identified phenomenon.

For example, a body of knowledge exists regarding the attitudes of occupational therapy faculty toward including students with disabilities in occupational therapy education. However, little is known about the attitudes of other public health faculty toward including these students in graduate education. Therefore, research based on a Level 1 question will be meaningful and appropriate to describe the attitudes of public health faculty toward accepting and teaching students with diverse disabilities in their graduate classes. Level 1 questions focus on a description of one concept or variable in a population. To describe a variable, which can be defined as a characteristic or phenomenon that has more than one value, you must first derive a lexical definition of the concept from the literature and operationalize or define it in such a way as to permit its measurement. Thus, Level 1 questions focus on measuring the nature of a particular phenomenon in the population of interest.

In response to the changing context of practice, a recent study conducted by Hoppes and Hellman2 examined the attitudes of occupational therapy students toward community practice. Although there was a growing body of literature on the need to educate students for community practice, Hoppes and Hellman were concerned that “students’ voices have seldom been heard in the discussion about assimilating community engagement into occupational therapy education”. To inform progressive occupational therapy education that would be meaningful to students, these investigators initiated a descriptive study to answer the following research questions:

Do students believe there are specific actions they can take to address community needs?

Do students feel a moral obligation to help in their communities?

How do students perceive the costs and benefits of helping in their communities?

To what extent are students aware that needs exist in their communities?

To answer these questions, the investigators identified specific items on the Community Service Attitudes Survey that measured each of the variables names in the four Level 1 questions. Occupational therapy students were used as their population of interest. Box 7-1 presents additional examples of Level 1 questions. Note that they answered the questions “what?” and “how much?”

Think about the basic, descriptive research questions in the previous examples. What is the main concept or variable that will need to be measured in Question 1? It is the most common adaptive equipment being requested. What is the primary population that will need to be recruited? It is elders in Sweden applying for grants for assistive devices. Question 2 seeks to describe the variable of functional status over time, and Question 3 measures the variable of family problems, defined as substance use, psychopathology, compulsive disorders, and violence in a population of social work students.

As you can see, the focus of a Level 1 question is on “the what” and “how much.” Level 1 questions focus on the description of one concept or variable in a population. A variable can be defined as a characteristic or phenomenon that has more than one value. To describe a variable, you must first derive a lexical definition of the concept (description of the term in words) from the literature and then operationalize it (define a concept by how it will be measured). As an example, in the study by Sellers and Hunter,4 the lexical definition of family problems is defined by the presence of substance use, psychopathology, compulsive disorders, and violence in one’s family of origin or childhood.

Level 1 questions focus on measuring the nature of a particular phenomenon in the population of interest. These types of questions use the stem of “what are” or “what is” and refer to one population. As shown in the examples, only one population is identified, such as elders applying for financial support in Sweden, elders with depressive symptoms, and social work students. Also, single concepts are examined in each study, such as assistive devices, functional status, and family disorders. Each of these concepts can be defined in such a way to permit their measurement; that is, they can be examined empirically.

Level 1 questions describe the parts of the whole. Remember, the underlying thinking process for experimental-type research is to learn about a topic by examining its parts and their relationships. Level 1 questioning is the foundation for clarifying the parts and their specific nature. In the scheme of levels of abstraction, Level 1 questions target the lowest levels of abstraction: concepts and constructs (see Chapter 6).

As discussed in later chapters, Level 1 questions lead to the development of descriptive designs, such as surveys, exploratory or descriptive studies, trend designs, feasibility studies, need assessments, and case studies.

Level 2: Questions That Explore Relationships Among Phenomena

The Level 2 relational questions build on and refine the results of Level 1 studies. Once a “part” of a phenomenon is described and there is existing knowledge about it in the context of a particular population, the experimental-type researcher may pose questions that are relational. Level 2 reflects relational questions and builds on and refines the results of Level 1 studies. The key purpose of Level 2 type of questioning is to explore relationships among phenomena that have already been identified and described. Here the stem question asks, “What is the relationship?” or a variation of this (e.g., “association”), and the topic contains two or more concepts or variables. “What is the relationship between exercise capacity and cardiovascular health in middle-aged men?” In this case, the two identified variables that are measured are exercise capacity and cardiovascular health. The specific population is middle-aged men. As you can surmise, Level 1 research must have been accomplished for the two variables to be defined and operationalized.

Returning to the example of attitudes of public health faculty, suppose we now want to know the relationship between attitudes and numbers of students admitted into public health majors. We would pose a Level 2 question such as, “What is the relationship between faculty attitudes and number of public health majors with mobility impairments. This Level 2 question would lead us to measure and look at the association between two variables, attitudes and number of majors admitted to public health programs. Suppose we found that negative attitudes were related to low numbers of public health majors with mobility impairments. We would be able to claim an association but not a causal relationship between the two variables.

Let us revisit the Level 1 examples and see how they can be modified to become Level 2 questions. Suppose we have conducted studies to address the Level 1 questions in Box 7-1. If we continue our research agenda in each of these areas of inquiry, we would be ready for the relational questions in Box 7-2.

Level 2 questions address relationships between variables. Studies with this level of questioning represent the next level of complexity above Level 1 questions. These questions continue to build on knowledge in the experimental-type framework by examining their parts, their relationships, and the nature and direction of these relationships. Level 2 questions primarily lead to research that uses passive observation design, as discussed later in the text. Refer to the levels of abstraction in Chapter 6 and see where Level 2 questions fit in the schema of building knowledge in the experimental tradition.

Level 3: Questions That Test Knowledge

Level 3 questioning builds on the knowledge generated from research conducted in Level 1 and Level 2 investigations. A Level 3 question asks about a cause-and-effect relationship among two or more variables, with the specific purpose of testing knowledge or the theory behind the knowledge. We refer to this as a predictive question. Given the findings of the Level 2 question, it would be important to know whether attitudes are causal of barriers to public health education for students with mobility impairments. A Level 3 question would therefore be indicated. Building on the knowledge already generated, we now would be able to ask the following question: “To what extent do faculty attitudes influence the number of students with mobility impairments who are accepted into public health majors?” The resultant study will test the theory behind the reasons that negative attitudes create educational barriers, and the study will be able to predict the opportunity for these students to be accepted into public health majors on the basis of faculty attitudes. At this level of questioning, the purpose is to predict what will happen and provide a theory to explain the reason(s). On the basis of a Level 3 question, specific predictive hypotheses, statements predicting the outcome of one variable on the basis of knowing another, are formulated. Action based on this knowledge can be taken to promote educational opportunity if you know where, why, and how to intervene.

In a Level 3 question, it is already established that two concepts are related, based on previous research findings (from Level 2 research). The point of study at Level 3 is to test these concepts in action by manipulating one to affect the other. Level 3 is the most complex of experimental-type questioning. Once the foundation questions formulated at Levels 1 and 2 are answered, Level 3 questions can be posed and answered to develop knowledge—not only of parts and their relationships, but of how and why these parts interact to cause a particular outcome. Level 3 questions examine higher levels of abstraction, including principles, theories, and models.

Consider these examples from the two studies discussed earlier that contain Level 3 questions:

1. What factors predict a change over 3 years in depressive symptoms?

2. Do socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, and race/ethnicity) and the type and number of family problems affect the likelihood that master’s students in social work will view their decision to pursue a career in the field as influenced by a history of family problems?

Knowledge generated from these types of Level 3 studies would provide guidance to identify specific strategies for decreasing depressive symptoms and for recruitment of social work students, respectively. In other words, each study would provide knowledge regarding where, why, and how to act.

Now consider another type of Level 3 question.

Level 3 questions assume that two concepts are related, based on findings from previous Level 2 research studies. The main purpose of Level 3 studies is to test these concepts in action by manipulating one to affect the other. Level 3 is the most complex of experimental-type questioning. Once the foundational questions formulated at Levels 1 and 2 are answered, Level 3 questions can be posed and answered to develop knowledge of not only the parts and their relationships but also how and these parts interact to cause a particular outcome. Level 3 questions examine higher levels of abstraction, including principles, theories, and models (see Chapter 6).

To answer a Level 3 question, research action processes capable of revealing causal relationships among variables must be implemented. A true experimental design or a variation would need to be conducted.

Developing Experimental-Type Research Questions

As you see, question formulation for experimental-type research is relatively straightforward. You can refer to Table 7-1 as a basic guide in helping you develop research questions at the three levels. Also, Box 7-3 provides helpful rules for developing questions at the appropriate level.

Keep in mind that one challenge in developing an experimental-type research question, particularly for new researchers, is proposing a question that is (1) very specific, (2) not too broad, and (3) feasible to study. One tendency is to develop a question that is too “big.” If your question can be broken down into subquestions, you know you have not yet developed an appropriate research question.

Hypotheses

As discussed in previous chapters, experimental-type researchers frequently engage in studies that involve hypotheses. A classic definition of hypothesis is “a proposition to be tested or a tentative statement of a relationship between two variables.”5

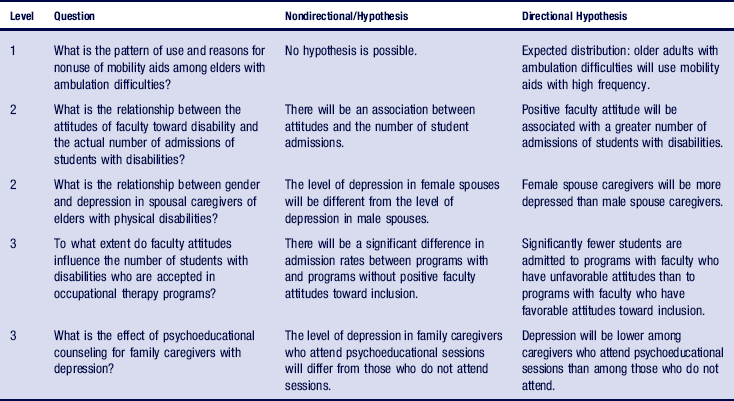

As the definition implies, hypotheses are primarily necessary and developed for Level 2 and Level 3 questions. For a Level 1 question, the experimental-type researcher usually has a “hunch” about the expected distribution of a single variable; however, a statement about a single variable is no a hypothesis. By definition, a Level 1 question does not have the essential elements of at least two variables and a statement of expected relationship.

Although a hypothesis is a researcher’s best hunch about a phenomenon, this “guess” does not emerge from thin air. Rather, it must be based on existing literature and theory and must stem from the research question guiding the study.

Hypotheses serve important purposes in experimental-type research. First, they form an important link between the research question and the design of the study. In essence, hypotheses rephrase the research question and turn it into a testable or measurable statement. Second, hypotheses may identify the anticipated direction of the proposed relationship between stated variables. Information regarding directionality of a relationship between variables is usually not contained in the actual research question.

The two types of hypothesis are directional hypothesis and nondirectional hypothesis. As an example, in formulating a hypothesis on the causal relationship between faculty attitudes and educational opportunity in public health majors, we might state a nondirectional hypotheses such as:

A directional hypotheses might look like:

Negative faculty attitudes are associated with lower admission rates for students with mobility impairments in public health curricula.

Notice that this statement does not suggest or state an expected cause but rather states a direction in a proposed relationship.

A third and critical purpose of hypotheses is that these purposefully constructed statements “set the stage” for the type of statistical analyses that will be used. We discuss these logical thinking processes and actions later in the book.

Table 7-2 provides examples of hypotheses for each type of experimental-type research question.

Research queries in naturalistic inquiry

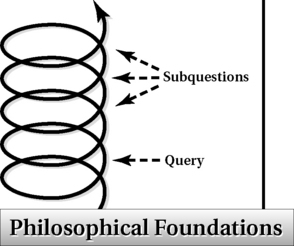

Now we turn to a completely different approach to formulating research. In naturalistic inquiry, formal entry into a study requires the initial development of a broad query. Although various philosophical perspectives inform inquiry within naturalistic research, as previously discussed, and although the task of framing the problem and query are somewhat different among varied approaches, there is some underlying similarity to problem development.

Researchers in the naturalistic tradition generally begin by identifying a topic and a broad problem area or specifying a particular phenomenon from which a query is pursued. We thus use “query” to refer to a broad statement that identifies the phenomenon or natural field of interest and to distinguish naturalistic and experimental-type traditions in this action step.

The natural field where the phenomenon occurs forms the basis for discovery from which more specific and limited questions evolve in the course of conducting the research. Thus, the initial entry into the field is based on a query statement that identifies the phenomenon of interest and the location and population or community that will be the focus. Then, once in the field and as new insights and meanings are obtained, the initial problem statement and query are reformulated. On the basis of new insights and issues that emerge in the field, the investigator formulates smaller, concise subquestions that are subsequently pursued in the field. These smaller questions are contextual; that is, they are derived inductively from the context itself and are rooted in the investigator’s ongoing efforts to understand the broad problem area. In turn, each smaller question that is posed may lead the investigator to use a different methodological approach. This interactive questioning-data gathering-analyzing-reformulating of the questions and initial query represents a critical and core action process of naturalistic inquiry.

Let us examine the process by which a research query is developed and then reformulated in three qualitative methodological approaches within the naturalistic tradition. As you read on, think about what is similar and what is different about the formulation and reformulation of queries.

Classic Ethnography

As the primary research approach in anthropology, ethnography is concerned with describing and interpreting cultural patterns of groups and understanding the cultural meanings people use to organize and interpret their experiences.6 In this approach, the researcher assumes a “learning role” to interpret and experience different cultural settings. The information gathered bridges the world and culture of the researcher to that of the researched.7 After the ethnographer has identified a phenomenon and cultural setting, a query is pursued.8 There is always a strong descriptive element in ethnography, so the ethnographic question must implicate what the ethnographer is to describe. You haven’t posed an ethnographic question until it is clear what the ethnographer is to look at and to look for at least with sufficient clarity to initiate an inquiry.

If time and resources allow, the luxury of such broad questions as what is going on here or what do people in this setting have to know in order to do what they are doing are adequate for an inquiry.8

Further, Wolcott highlighted the purposive aspect of ethnographic questions.

As you can see, experimental-type questions and hypotheses stand in stark contrast to the interpretative-opened, purposive query posed initially by the ethnographer.

As the processes of data gathering and analysis proceed in tandem, specific questions emerge and are pursued. These questions emerge in the field as a consequence of what Agar classically labeled as breakdowns, or disjunctions, a concept which we still find useful and central to ethnographic inquiry. “A breakdown is a lack of fit between one’s encounter with a tradition and the schema-guided expectation by which one organizes experience.”6 A breakdown represents the difference between what the investigator observes and expects to observe. These differences stimulate a series of questioning and further investigation. Each subquestion is related to the broader line of query and is investigated to resolve the breakdown and develop a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon in its entirety. An ethnographic query therefore establishes the phenomenon, the setting of interest, or both. The query also sets up the thinking and action processes necessary to understand the boundaries.

To summarize, once a query has been posed, questioning occurs simultaneously with collecting information and making sense of it. One process drives the other. The interactive questioning, data gathering, and analytical processes result in the reformulation and refinement of the problem and the structuring of small subquestions. These subquestions are then pursued in the field to uncover underlying meanings and cultural patterns.

Health and human service professionals have used ethnographic methods, such as interviewing and participant observation (discussed more fully in subsequent chapters), to examine cultural variations in response to disability, adaptation, health services utilization, health care practices, and other related areas.

Phenomenology

The purpose of the phenomenological line of inquiry is to uncover the meaning of a human experience or phenomenon typically of more than one individual, through the description of those experiences as they are lived by individuals.9 The first research step from this perspective is to identify the phenomenon of investigation.

This approach is different from ethnography in that phenomenological queries focus on particular experiences (e.g., grief, birth of a child, divorce, illness, and disability) from the perspective of the individuals and do not seek to understand group or cultural patterns. However, similar to ethnography, the research begins with a broad query. On the basis of what the investigator knows through the action of conducting the research, subquestions and specific inquiries are developed that further inform the overarching query related to the meaning of experience for the individuals participating in the study.

As example, Vikers used a phenomenological approach to explore the experience of people with multiple sclerosis who have left work.10 Different from assumptions that loss of health and function from the disease was the primary cause, Vikers found that this phenomenon was experienced in diverse ways with diverse meanings beyond the disease process.

Grounded Theory

Grounded theory is a method in naturalistic research that is used primarily to generate theory.11 The researcher begins with a broad query in a particular topic area and then collects relevant information about the topic. As the action processes of data collection continue, each piece of information is reviewed, compared, and contrasted with other information. From this constant comparison process, commonalities and dissimilarities among categories of information become clear, and ultimately a theory that explains observations are inductively developed. Thus, queries that will be answered through grounded theory do not relate to specific domains but to the structure of how the researcher wants to organize the findings (Box 7-4).

As you can see, each query indicates that the research aim is to reveal theoretical principles about the phenomenon under study. Grounded theory can also be used to modify existing theory or to expand on or uncover differences from what is already known. In the two queries in Box 7-5, grounded theory is structured to address current theory from a new and inductive perspective.

Narrative

Although there is no single definition of narrative,12 all have two common elements, storytelling and meaning making. In general, narrative methods are interpretive strategies used in diverse disciplines and fields but are particularly popular in postmodern studies such as women’s studies and disability studies. Synthesizing the diverse definitions of narrative, we define it as a naturalistic method in which stories are told and inductively analyzed for meaning. Stories can be generated by an individual or group in response to a query or can exist in the form of text or even image. However, regardless of the form, the data must tell a story that can be interpreted. Mesinga13 demonstrated five different approaches to narrative, all of which investigated career choice. Although the studies themselves did not identify specific queries, the initial entry point into each was a broad statement about the evolution of career choice and its meaning to the informants who generated the stories. Life history is a type of narrative in that it tells a story about the chronology of a life and the meaning of events within that life.

Developing Naturalistic Research Queries

Ethnography, phenomenology, and grounded theory reflect distinct approaches in naturalistic inquiry. Queries developed within each methodology and design reflect a different purpose and a preferred way of knowing and are shaped by the particular resources available to the investigator. Nevertheless, underlying each of these approaches is an essential iterative process of query-subquestion-reformulation that is central to the structuring of the research enterprise in naturalistic inquiry.

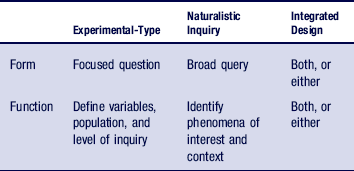

Integrating research approaches

Another important category of research is referred to as integrated designs. Table 7-3 includes this category in summarizing experimental and naturalistic question/query formulation. Integrated designs combine different research traditions and approaches and, by their nature, may be complex. As such, these designs may rely on the formulation of a query, a question, or both and may order the formulation of these in diverse ways to accomplish the overall research purpose.

Consider the following examples to highlight the differences in approach among the experimental-type and naturalistic research traditions and an integrated design.

A health care research team is interested in studying disparities in access to end-of-life health care among individuals whose income is just above the poverty line. On the basis of the large body of literature on access to health care, the researchers conduct a secondary analysis of case data to answer the following Level 1 experimental-type question:

In this study, the investigators find that there is a disproportionate underrepresentation of low-income individuals in palliative care, and they thus set out to investigate why.

Once again, relying on theory and research that has been generated in similar studies, they develop a study in which they identify the variables of provider recommendation and geographic diversity that promote or inhibit palliative care and pose the following Level 2 questions:

How is provider recommendation related to a family’s decision to seek palliative care for a dying family member in a low-income population?

What differences in urban versus rural populations exist in decisions to seek palliative care?

While the Level 1 and Level 2 questions are productive in identifying variables that may be predictive of a decision to seek palliative care, the investigators decide that the literature does not provide sufficient theory about decision-making processes. They therefore plan a naturalistic study to answer the following queries:

How do low-income families decide to seek palliative care for their loved ones?

What experiences and life circumstances are important in decisions to seek or not to seek palliative care?

The investigators in this example initially isolated constructs and variables relevant to their areas of study that favor experimental-type design. The constructs posed in the research question were identified from reading the research literature, from practice experience, or from federal funding initiatives that define poverty level and related health benefits and that suggest geographic differences. Thus, Level 1 and Level 2 questions were appropriate. However, once decision-making processes and experiences became central to the research agenda, the investigators moved to an epistemological framework based in naturalistic tradition. The investigators proceed inductively, on the basis of the framework that there are multiple decision pathways, experiences, and realities that need to be discovered and understood to derive a comprehensive view of the decision to seek palliative care. Based on an understanding of different realities of and choices to pursue end-of-life options which will emerge in the course of the study, comprehensive clinical guidelines can then be developed and further evaluated.

An integrated study may pose both a concise question and a query, and the studies may be conducted sequentially or simultaneously.

As shown, integrated designs can be complex. Therefore it is important for the investigators to clearly articulate the specific questions and queries that are posed jointly and to delineate how each contributes to the other.

Summary

There are many ways to frame a research problem. Each approach to problem formulation and query or question development differs within the two traditions of research design. In experimental-type design, the question drives each subsequent research step. Refinement of a research question occurs before any further action processes can be implemented. Conciseness and refinement are critical to the conduct of the study and are the hallmarks of what makes the research question meaningful and appropriate. Experimental-type questions are definitive, structured, and derived deductively before the researcher engages in specified actions.

In naturalistic inquiry, the query establishes the initial entrance and boundaries for the study but is reformulated in the actual process of collecting and analyzing data. The researcher fully expects and prepares for new queries and subquestions to emerge in the course of conducting the study. That is, refinement of query and question emerges from the action of conducting the research. The development of specific questions occurs inductively and emerges from the interaction of the investigator within the field or with the phenomenon of the study. Thus, an initial research question and query have different levels of meaning and implications for the conduct of studies in experimental-type design and naturalistic research. Research queries and subquestions are dynamic, ever changing, and derived inductively.

Integrated studies use the strengths of both experimental-type and naturalistic traditions to pose questions and queries that can reveal, describe, relate, or predict.

References

1. Gitlin, L.N., Levine, R., Geiger, C. Adaptive device use in the home by older adults with mixed disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:149–152.

2. Hoppes, S., Hellman, C. Understanding occupational therapy Students' attitudes, intentions, and behaviors regarding community services. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2007;61(5):527–534.

3. Mann, W., Johnson, J., Lynch, L., et al. Changes in impairment level, functional status, and use of assistive devices by older people with depressive symptoms. Am J Occup Ther. 2008;62:9–17.

4. Sellers, S.L., Hunter, A.G. Private pains, public choices: Influence of problems in the family origin on career choices among a cohort of MSW students. Social Work Education. 2005;24:869–881.

5. Neuman, W.L. Social research methods: qualitative and quantitative approaches, ed 5. Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 2003.

6. Agar, M. Speaking of ethnography. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage, 1986;21.

7. Farber, M. The aims of phenomenology: the motives, methods, and impact of Husserl’s thought. New York: Harper & Row, 1966.

8. Wolcott, H.F. Writing up Qualitative Research, 3rd ed. Sage Publications, 2009.

9. Creswell, J. Qualitative inquiry and research design. Thousand Oaks: CA, Sage, 2007.

10. Vickers, M.H. Why people with MS are really leaving work: From a Clayton’s choice to an ugly passage. Rev Disabil Studies Int J. 2008;4:43–57.

11. Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis (Introducing Qualitative Methods series). Sage Publications, 2006.

12. Clandinin, M. Narrative inquiry: a methodology for studying lived experience. Res Studies Music Educ. 2006;27:44–54.

13. Mensinga, J. Storying career choice: employing narrative approaches to better understand students’ experience of choosing social work as a preferred. Qual Soc Work. 2009;8:193–209.

You are a therapist working in a rehabilitation center. One of your responsibilities is to introduce patients to a range of adaptive equipment that they may need or may find useful in the hospital and on their return home. You notice, however, that some of your older patients appear hesitant to use this equipment, and you are not convinced that they continue to use the issued assistive devices once they are home. Because this has important practice, policy, and cost implications, you and your department consider this concern important enough to investigate.

You are a therapist working in a rehabilitation center. One of your responsibilities is to introduce patients to a range of adaptive equipment that they may need or may find useful in the hospital and on their return home. You notice, however, that some of your older patients appear hesitant to use this equipment, and you are not convinced that they continue to use the issued assistive devices once they are home. Because this has important practice, policy, and cost implications, you and your department consider this concern important enough to investigate.