Collecting Information

You now have a better understanding of the methods for involving individuals, events, observations, and artifacts in your study. Now let us explore the various strategies you can use to collect information or data. This chapter provides an overview of the action process of gathering information to answer research questions or queries. A number of strategies are discussed, some of which are used exclusively in experimental-type research or in naturalistic inquiry. Subsequent chapters examine the specific approaches used in each research tradition.

In experimental-type research, data collection is a distinct action phase that represents the crossroads between the thinking processes involved in question formation, development and implementation of design, and the action process of analysis. Strategies for data collection involve actions that are pertinent to the research problem and consistent with the design. In turn, the types of data collected and the methodological approach used to obtain information shape both the type and nature of the analytical process and the understandings and knowledge that can emerge.

In naturalistic inquiry, gathering information stems from the initial query. However, it is embedded in an iterative, abductive approach that involves ongoing analysis, reformulation, and refinement of the initial query.

Principles of information collection

Three basic principles characterize the process of collecting information within the different research traditions (Box 15-1).

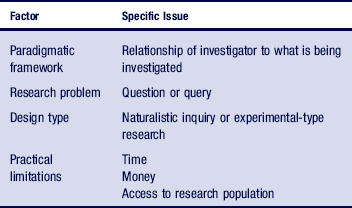

First, the aim of collecting information, regardless of how it is conducted, is to obtain data that are both relevant and sufficient to answer a research question or query. Second, the choice of a data collection or information-gathering strategy is based on four major factors: the researcher’s paradigmatic framework, the nature of the research problem, the type of design, and the practical limitations or resources available to the investigator (Table 15-1). Third, although the overall data collection strategy reflects the researcher’s basic philosophical perspective, a specific procedure, such as observation or interview, may be used by researchers conducting either a naturalistic or an experimental-type study. Many researchers find it useful to collect data and information with more than one procedure or technique to be able to answer a question or query more fully. The use of multiple collection techniques is referred to as “triangulation” or “crystallization” and is useful for increasing the accuracy of information.1 We discuss this technique in subsequent chapters.

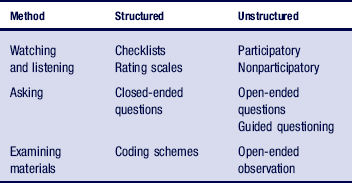

In general, the action process of data and information collection uses one or more of the following strategies: (1) looking, watching, listening, reading, and recording; (2) asking; and (3) obtaining and examining materials. Each of these strategies can be structured, semistructured, or open-ended, depending on the nature of the inquiry (Table 15-2). Also, each strategy can be used in combination with another.

Looking, watching, listening, reading, and recording

One important data collection and information-gathering strategy involves systematic observation. The process of observation includes five primary activities, which may be interrelated: looking, watching, listening, reading, and recording. The record produced by the investigator comprises the data set. The way in which the researcher looks, watches, reads, and listens may range from being structured to unstructured, participatory to nonparticipatory, narrowly to broadly focused, and time limited to ongoing and fully immersed.2

In the experimental-type tradition, observation is usually time limited and structured. Criteria to look, watch, listen, read, and record are determined a priori to gathering data, and the data are recorded as a structured measurement system. For example, checklists may be used that indicate the frequency (or only the presence or absence) of a particular behavior or object under study. Or a text may be read, and the occurrences of a particular phrase to denote “power language” might be counted and recorded. Phenomena other than those specified before entering the field are omitted from or remain outside the investigator’s record. Rating scales may also be used to record observations; the investigator rates the observed phenomenon on a scale with a predetermined point system (see Chapter 16).

Looking, watching, listening, reading, and recording take on an inductive quality in naturalistic designs, with varying degrees of participation and interaction between the investigator and the phenomena of interest. The investigator broadly defines the boundaries of observation (e.g., a community health center), then moves to a more focused observational approach (e.g., particular locations, navigation patterns, staff–client interactions, language, signs, images) as the process of collecting and analyzing information from previous observations unfolds.

Asking

Health and human service providers routinely ask a wide range of questions to obtain information for professional purposes. Similarly, in research, “asking” is a systematic and purposeful aspect of a data collection plan. As in observation, questions can vary in structure and content, from unstructured and open-ended questions to structured and closed-ended questions or fixed-response queries that use a predetermined response set.

Naturalistic research relies more heavily on open-ended types of asking techniques, whereas experimental-type designs tend to use structured, fixed-response questions. Focused, structured asking is used to obtain data on a specified phenomenon, whereas open-ended asking is used when the research purpose is discovery and exploration.

When asking, you can pose questions through interviews or questionnaires.

Interviews

Interviews are conducted through verbal communication; they may occur face-to-face, by telephone, or through virtual communication, and may be either structured or unstructured. Interviews are usually conducted with one individual. Sometimes, however, group interviews are appropriate, such as those conducted with couples, families, and work groups. Group interviews of five or more individuals may involve a focus group methodology in which the interaction of individuals is key to the information the investigator wants to obtain. This technique is particularly useful in attitudinal and participatory research in which group think is desirable.3 An audiotape of the group interview is transcribed, and the narrative (along with investigator notes) forms the information base, which is then analyzed. (See Chapter 17 for more detail.)

Structured interviews rely on a written questioning protocol (sometimes referred to as an interview schedule) in which maximum researcher control is imposed on the content and sequencing of questions. Each question and its response alternatives are developed and placed in sequential order before an interview is conducted. Interviewers are instructed to ask each question precisely as it is written in the protocol. Most questions are closed-ended or fixed; that is, subjects select one response from a predetermined set of answers. Closed-ended questions vary with regard to the type of response alternatives (Box 15-2). Each response set forms a different type of scale, as discussed later in this chapter.

In a structured interview, the investigator may use a few open-ended questions. However, responses are then examined to derive categories, which are coded and, in effect, changed into a closed-ended response set on a post hoc analytical basis; that is, the investigator develops a numerical coding scheme based on the range of responses obtained and assigns a code to each subject. The numerical response is then analyzed.

Unstructured interviews are primarily used in naturalistic research and in exploratory studies with experimental-type designs. The researcher initially presents the topic area of the interview to a respondent, then uses probing questions to obtain the desired level of detailed information. The interview may begin with an explanation of the study purpose and a broad statement or question such as, “Could you please describe your experience at our assistive technology center?” Other probing questions emerge as a consequence of the information provided from this initial query. Probes are statements that are neutral or, to the extent possible, that do not bias the respondent to answer in any particular way. Probes are used to encourage the respondent to provide more information or to elaborate. A probe (e.g., “Tell me more about it,” or simply repeating a question) encourages a respondent to discuss an issue or elaborate on an initial response.

Quantitative researchers sometimes use unstructured interviews in pilot studies to uncover domains and response codes for future inclusion in a more structured interview-and-question format.

Questionnaires

Questionnaires are written instruments and may be administered face-to-face, by proxy, through the mail, or over the Internet. Similar to interviews, questionnaires vary as to whether questions are structured or unstructured. (The process of developing questionnaires is examined in Chapter 16 as part of the discussion on measurement in experimental-type research.)

Each way of asking—structured or unstructured—has strengths and limitations that the researcher must understand and weigh to determine the most appropriate approach. There is no “best way” of collecting information. The strengths and limitations of structured (closed-ended) questions must be evaluated in terms of the researcher’s purpose (Boxes 15-3 and 15-4). Consider the following example.

Using this example, now consider the advantages of open-ended (unstructured) questions (Box 15-5). Then, identify the limitations of an open-ended approach and see whether you can apply these to the example (Box 15-6).

As you can see, both structured asking and unstructured asking have merits and limitations, depending on the research purpose, phenomena to be studied, and study population.

Obtaining and examining materials

Materials are defined as objects, information, phenomena, or data that already exist. There are numerous reasons to seek out and use existing materials. First, direct observation and interview may not be possible, and thus an investigator may try to answer the research question by seeking a data set that has already been generated in the topic area of interest. Consider the investigator who is conducting inquiries of a sensitive nature, where informants may not want or be able to share their experiences. Seeking information that has already been obtained and organized not only makes sense for the researcher but also saves further discomfort on the part of respondents. Second, the use of existing materials eliminates the attention factor, or the Hawthorne effect4 (change in respondent’s answer as a consequence of participating in the research process). Third, using existing materials allows the researcher to view phenomena in the past and over time, which may not be possible with a primary data collection strategy that occurs at one point.

As with asking and observing, securing and examining materials in experimental-type design are structured by criteria before the research field is entered. In naturalistic inquiry, the selection of materials to observe or examine emerges as a consequence of the investigative process. Although there are many ways to use existing materials, we organize them here into three distinct approaches: (1) unobtrusive methodology, (2) secondary data analysis, and (3) artifact review.

Unobtrusive Methodology

Unobtrusive methodology involves the observation and examination of documents, objects, and environments that bear on the phenomenon of interest.5 This methodology is nonreactive; that is, there is minimal or no discernible investigator effect in the research setting.

Consider also the investigator who examines text and interactions on social networking Web sites to ascertain the answer to a research question. Investigators may use many sources for text-based materials in their analysis (Box 15-7).

Secondary Data Analysis

In secondary data analysis, the researcher reanalyzes one or more existing data sets.6 By “data set,” we mean information that has been obtained and organized for the purpose of research.

The purpose of a secondary analysis is to ask different questions of the data from the data set analyzed in the original work. Researchers use several large, national health and social service data sets for secondary data analysis. For example, the census tracts, Kids Count, National Health Interview Surveys, National Health Care Data Set, Medicare and Medicaid data, Annual Housing Survey, and court report recordings are important sources for secondary analysis in health and human service research.

Geographic Data

Geographic data are increasingly being used to answer research questions of interest to health and human service providers. With the expansion and advancing sophistication of computer programs that can map and depict levels of spaces and geographies, questions regarding the public health and service needs of regions, as well as place-related epidemiology, risks and strengths, health disparities, and resources can be systematically informed. Because health and human service problems, needs, and efforts are geographically situated, contemporary statistical modeling methods and geospatial inquiry delimited to local communities provide the tools through which to develop models relevant to health and human service questions. Moreover, these models can be statistically manipulated to predict the relationships among social and health problem prevalence and the availability, proximity, and nature of prevention resources in a geographic area.

There is a wide range of applications and complexity in geographic analysis, from static, slice-in-time snapshots, to temporally changing dynamic modeling.7 What all geographic data have in common are the use of visual spatial locations as delimiters of information and analysis. The Geographic Information System (GIS) relies on two overarching spatial paradigms, raster and vector. Raster GIS carves geography into mutually exclusive spaces and then examines the attributes of these. Thus, the attributes of one space can be represented and compared with the attributes of another.

Vector GIS relies on location points. This approach locates points and identifies spaces and the attributes delimited inside of them by the lines that connect the points. Each approach has its strengths and limitations, but both have valuable applications.

Information in the Virtual and Information Technology Environment

As we have discussed throughout this chapter and the book, the Internet, among other digital formats such as podcasts, text messaging, and cellular images, is becoming a major source of information and thus provides a rich environment for obtaining information in all research traditions. Experimental-type and naturalistic data on the Internet can parallel the structure and content of data in the physical world. Thus, survey data can be generated, secondary data can be obtained, and data for naturalistic observation and analysis can be developed and or unobtrusively accessed, as we have discussed. However, some information can only be created or accessed virtually, as exemplified by geospatial data that is rendered in multidimensional layers. Two major advantages of conducting research in the virtual environment are reach and multiplicity of formats.

Reach refers to the global scope of the internet. Information can be obtained instantaneously from across the continent, the ocean, or even beyond. We can now connect to the Internet and cellular towers in airplanes, allowing for information to be obtained and considered from locations that are not even situated on terra firma.

Multiplicity of formats refers to the capacity of the virtual environment to present information in text, orally and in images. Because the virtual environment is a digital medium, the survey in the previous example could be obtained in text, oral, or image format on a cellphone, MP3 player, or computer. Of course, you would test differences related to format in your research, because this could be a confounding variable or influence in shaping knowledge.

Artifact Review

Artifact review is a technique primarily used to ascertain the meaning of objects in research contexts. For example, archaeologists examine ruins to learn about ancient cultures. Artifact review in health and human service research may include the examination of personal objects in a patient’s hospital room or client’s home to determine interests and preferred ways of arranging the environment as a basis for intervention planning.

Summary

Three basic principles guide the action process of obtaining information: (1) collecting relevant and sufficient information for the research question or query; (2) choosing an information-gathering or data-collecting strategy that is consistent with the research question, epistemological foundation, design, and practical constraints of the research effort; and (3) recognizing that methods can be shared across traditions. The categories of collecting information in all designs are looking, watching, reading, listening, and recording; asking questions; and examining materials.

We are now ready to examine specific data collection strategies in experimental-type design (Chapter 16) and gathering information in naturalistic design (Chapter 17).

References

1. Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S. Handbook of qualitative research, ed 2. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2000.

2. Patton, M. Qualitative evaluation and research methods, ed 3. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2001.

3. Bloor, M., Frankland, J., Thomas, M., Robson, K. Focus groups in social research. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2001.

4. Babbie, E. Practice of social research, ed 12. Belmont, Calif: Wadsworth, 2009.

5. Lee, R.M. Unobtrusive measures in the social sciences. Boston: Open University Press, 2000.

6. Stewart, D.W., Kamins, M.A. Secondary research: information sources and methods, ed 2. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 1992.

7. Worboys, M.F. Modeling changes and events in dynamic spatial systems with reference to socio-economic units. In: Frank A.U., Raper J., Cheylan J.P., eds. Life and motion of socio-economic units. London: Taylor and Francis; 2001:129–138.

8. Albrecht, J. Key Concepts and Techniques in GIS. Sage Publications, 2007.

Let us examine the concept of “intelligence” to illustrate different observational approaches. In experimental-type studies, intelligence testing relies largely on the use of a structured instrument that involves paper-and-pencil or computer-based tests and a tester observing a subject’s performance in a laboratory setting. Measurements are obtained on dimensions that have been predefined as composing the construct of intelligence. Typically, a score or set of scores will denote the magnitude of an individual’s intelligence. In a naturalistic approach, however, rather than using predefined criteria, the investigator may watch and listen to persons in their natural environments to reveal the meaning of intelligence and the ways it is recognized and responded to in a particular culture. Each approach has its value in addressing specific types of research questions or queries. Structured observation of intelligence is appropriate for the investigator who wants to compare populations or individuals, measure individual or group progress and development, or describe population parameters on a standard indicator of intelligence. In contrast, naturalistic observation of intelligence is useful to the researcher attempting to develop new understandings of the construct.

Let us examine the concept of “intelligence” to illustrate different observational approaches. In experimental-type studies, intelligence testing relies largely on the use of a structured instrument that involves paper-and-pencil or computer-based tests and a tester observing a subject’s performance in a laboratory setting. Measurements are obtained on dimensions that have been predefined as composing the construct of intelligence. Typically, a score or set of scores will denote the magnitude of an individual’s intelligence. In a naturalistic approach, however, rather than using predefined criteria, the investigator may watch and listen to persons in their natural environments to reveal the meaning of intelligence and the ways it is recognized and responded to in a particular culture. Each approach has its value in addressing specific types of research questions or queries. Structured observation of intelligence is appropriate for the investigator who wants to compare populations or individuals, measure individual or group progress and development, or describe population parameters on a standard indicator of intelligence. In contrast, naturalistic observation of intelligence is useful to the researcher attempting to develop new understandings of the construct.