Analysis in Naturalistic Inquiry

We now turn our attention to the way in which researchers approach the analysis of data in naturalistic inquiry. As you probably surmise at this point, the action process of conducting analyses in naturalistic inquiry is quite different from the actions taken during statistical decision making in experimental-type research. Analysis in naturalistic research is a dynamic and iterative process. Also, as noted in Chapter 18, keep in mind that organizing information in naturalistic inquiry is an analytical action, and it is difficult to separate organization and management actions from analytical actions.

Although all analytical strategies reflect a logical approach, there is no step-by-step, recipe-like set of rules that can be followed by an investigator in naturalistic inquiry. Many organizational and analytical strategies can be used at different points in the process. The analytical process also depends on the type of data that are collected, and it will vary depending on whether the data are narrative, observational, visual, musical, diaries, or other data formats.

After you read this chapter, you may want to refer to other literature sources to obtain more in-depth and specific understanding of particular analytical approaches in naturalistic inquiry.1–4 Here we provide a full introduction to and overview of the basic principles that underlie the general thinking and action processes of researchers involved in various forms of analysis across the traditions of naturalistic inquiry.

Strategies and stages in naturalistic analysis

Many purposes inform the analytical process in naturalistic inquiry. The selection of a particular approach to analysis depends on the primary purpose of the research study, the scope of the query, and the particular design. Table 20-1 summarizes the basic purpose and analytical approach used by seven designs in naturalistic inquiry.

TABLE 20-1

Purpose and Analytical Strategy of Naturalistic Study Designs

| Study Design | Main Purpose | Basic Analytical Strategy |

| Endogenous | Varies | Varies |

| Participatory action research | Varies | Varies |

| Phenomenology | Identifies essence of personal experiences | Groups statements based on meaning; develops textual description |

| Heuristic | Discovers personal experiences | Describes meaning of experience for researcher and others |

| Life history | Provides biographical account | Describes chronological events; identifies turning points |

| Ethnography | Describes and explains cultural patterns | Identifies themes and develops interpretive schema |

| Grounded theory | Constructs or modifies theory | Provides constant comparative method to name and frame theoretical constructs and relationships |

Some analytical strategies in naturalistic inquiry are extremely unstructured and interpretive, such as in phenomenology, heuristic approaches, and some ethnographic studies. Other analytical strategies are highly structured, as in grounded theory. Still other types of naturalistic inquiry may incorporate numerical descriptions and may vary in the type of analysis used, as in certain forms of ethnography, endogenous approaches, and participatory action research. Further, some forms of naturalistic inquiry are highly interpretive but use a specific analytical strategy, such as in life history. In this type of study, the investigator searches for “epiphanies,” or key turning points, in the life of the individual(s) under study, using a chronological or biographical account as the basis from which interpretations are derived. Each analytical approach provides a different understanding of the phenomenon under study and reveals a distinct aspect of field experience. Furthermore, in any given study, a researcher may use a combination of analytical strategies at different points in the course of fieldwork.

Therefore, you would need to use three analytical approaches in this study. Each approach would reflect a specific purpose and yield a particular understanding of the phenomenon of interest. The findings from each approach would then be integrated to contribute to a comprehensive and integrative understanding of the initial research query (e.g., “What is the experience and meaning of living in assisted living?”).

Although each type of naturalistic design uses a different analytical strategy, the basic process across any type of naturalistic design can essentially be conceptualized as occurring in two overlapping and interrelated stages. The first stage of analysis occurs at the exact moment the investigator enters the virtual, conceptual, or physical field. It involves the attempt to make immediate sense of what is being observed and heard, or what is referred to as “learning the ropes.”2 At this stage the purpose of analysis is primarily descriptive and yields “hunches” or initial interpretations that guide data collection decisions made in the field. The second stage follows the conclusion of fieldwork and involves a more formal review and analysis of all the information that has been collected. The investigator refines or evolves an interpretation that is recorded in a written report for dissemination to the scientific community.

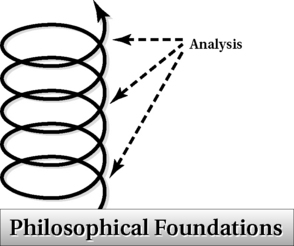

At each stage, the researcher may use a different analytical approach. The actions during each stage are best conceptualized as a “spiral” in which each loop of the spiral involves a set of analytical tasks that lead to the next loop in successive fashion until a complete understanding of the field or phenomenon under study is derived.

Stage one: analysis in the field

As shown in previous chapters, the process of naturalistic inquiry is iterative. Let us examine what this means in the initial analytical stage. First, data analysis occurs immediately as the researcher enters the field, and analysis continues throughout the investigator's engagement in the field. Analysis is the basis from which all subsequent field decisions are made: who to interview, what to observe, and which piece of information to explore further. Data collection efforts are inextricably connected to the initial impressions and hunches that are formulated by the investigator; that is, an observation, or datum, gives rise to an initial understanding of the phenomenon under study. This initial understanding informs or shapes the next data collection decision. Each collection-analytical action builds successively on the previous action.

Thus, during fieldwork, the researcher begins the process of systematically examining data—field notes, recorded observations, and transcriptions of interviews—to obtain initial descriptions, impressions, and hunches. It is important to note that transcriptions are usually completed immediately or shortly after the completion of an interview or observation to enable the investigator to evaluate the data and make subsequent field decisions to further the data collection efforts. The investigator also keeps careful records of his or her perceptions, biases, or opinions and begins to group information into meaningful categories that describe the phenomenon of interest. This descriptive analysis is especially critical in the early stages of fieldwork. It is essential to the process of reframing the initial query and setting limits or boundaries as to who and what should be investigated.

This initial set of analytical steps involves four interrelated thinking and action processes (Box 20-1). Keep in mind that these interrelated thinking and action processes are dynamic. That is, the four processes are not neat, separate steps or entities that occur in sequence at a particular time in fieldwork. Rather, they are ongoing, overlapping processes that lead to refinement of interpretations throughout the data-gathering effort.

Investigators, particularly those new to this type of inquiry, may feel overwhelmed and initially lost in this process. The sheer quantity of information generated in a short time can also make the investigator feel inundated. However, these feelings are a natural part of the experience of conducting naturalistic inquiry. The researcher must be able to feel comfortable with being in “limbo” at first, that is, not knowing the whole story and letting it unfold.

Engaging in Thinking Process

Naturalistic inquiry is based on either an inductive or an abductive thinking process (see Chapter 1). This thinking process is key to all the analytical approaches of naturalistic inquiry. One of the first analytical efforts of the researcher is to engage in a thoughtful process. This may seem basic to any research endeavor, but the active engagement of the investigator in thinking about each datum in naturalistic inquiry assumes a different quality and level of importance than in other research endeavors. David Fetterman described this basic analytical effort in ethnographic research as follows:

The best guide through the thickets of analysis is at once the most obvious and most complex of strategies: clear thinking. First and foremost, analysis is a test of the ethnographer's ability to process information in a meaningful and useful manner.5

More specifically, an inductive and abductive thinking process is characterized by the development of an initial organizational system and the review of each datum. The organizational system must emerge from the data. The investigator must avoid imposing constructs or theoretical propositions before becoming involved with the data. For example, in the case of data collected through an interview, the researcher will read and reread the transcriptions. From these initial readings, ideas and hunches will be formulated. In a phenomenological, heuristic, or life history approach, the investigator will continue working inductively until all meanings of an experience are explicated.

In an abductive approach, the thinking process begins inductively with an idea. The investigator explores information or behavioral actions and formulates a working hypothesis, which is examined in the context of the field to see whether it fits. The investigator works somewhat deductively to draw implications from the working hypothesis as a way of verifying its accuracy. This process characterizes the actions of the investigator throughout the field experience, especially for grounded theory6 and ethnography.7

In ethnography, Fetterman labeled this process “contextualization,” or the placement of data into a larger perspective.5 While in the field, the investigator continually strives to place each piece of data into a context to understand the “bigger picture” or how the parts fit together to make the whole. One way the investigator strives to understand how a datum fits into the larger context is by grouping information into categories.

Developing Categories

A voluminous amount of information is gathered within a short period in the course of fieldwork. The researcher will feel the need to manage the immense amount of data collected so quickly. Consider when you have had to review a large body of literature for a course in college. Perhaps you first went to the library to obtain information from the literature. You probably realized that your notes from the readings soon became overwhelming and that you needed to develop some organization to make sense of the information you gathered. The same principle applies in the initial stages of analysis in naturalistic inquiry. The researcher must find a way to organize analytically and make sense of the information as it is being collected.

One of the first meaningful ways in which the investigator begins to organize information is to develop categories, or “affinities.” We prefer the term categories for clarity and word recognition. Northcutt and McCoy8 noted the similarities between categories and variables, indicating that categories are single phenomena that can be named and in which multiple elements must occur. This action process represents a major step in naturalistic analysis. How do categories emerge? As Wax described:

The student begins “outside” the interaction, confronting behaviors he finds bewildering and inexplicable: the actors are oriented to a world of meanings that the observer does not grasp … and then gradually he comes to be able to categorize peoples (or relationships) and events.9

The researcher enters the field to see and understand phenomena without imposing concepts, labels, categories, or meanings a priori. Thus, categories emerge from researcher–field interactions and the initial information that is obtained and synthesized. Preliminary categories are developed and become the tools used to sort and classify subsequent information as it is received.

Categories represent the initial attempt to group in a meaningful way observations or phenomenon. Spradley and McCurdy10 described the process of generating categories as one of classifying objects according to their similarities and differences from other objects. Categories such as “student,” “provider,” and “client” make it easier to anticipate the behavior of individuals in these groups and to identify the cultural rules that govern their behavior. Categories are basic cultural elements that enable people to organize experiences. Categories are social inventions, because objects are not grouped in any natural way. These groupings change from culture to culture, time to time, and context to context. Categories can also reflect ways people describe their experience. For example, let's say you want to examine the way in which neighborhoods shape behaviors of community members. Your first level of analysis may be to group study participants' statements about and experiences in their neighborhoods by categories such as the physical dimensions, role of neighbors, and accessible and inaccessible features. Categories must be embedded within and reflect a cultural context and reveal at the most basic level the way in which a culture or group of study participants classifies objects and establishes a system of meanings.

How do you find or identify categories? In identifying categories, researchers must stay as close to the data as possible and not impose their own cultural categorization and labeling systems. One strategy is to search for commonalities among different objects, experiences, statements, images, or events. Agar7 suggested that recurrent topics are prime candidates for categories.7 Consider the following example:

As the data collection activity proceeds, the naturalistic investigator uses the original categories as the basis for analyzing new data. New data either are classified into existing categories or may serve to modify or create new categories to depict the phenomenon of interest accurately. Lofland, Snow, Anderson, and Lofland12 suggested that the researcher “file” data by placing them into categories on the basis of characteristics that the data share. The researcher decides on the filing scheme and considers both descriptive and analytical cataloging. Data placed in the descriptive categories answer “who, what, where, and when” queries and do not involve interpretation. Analytical or more interpretive categories answer “how and why” queries. Any one datum can be categorized in several ways. Thus, cross-coding or referencing the same excerpt or piece of information in multiple ways is important and adds another level of complexity to the coding process.

The development of categories is based on repeated review and examination of narrative, video, or other types of information that have been collected. The investigator assigns codes to each category. A number of methods can be used, depending on the investigator's personal style and preferences of working. For example, some researchers generate multiple copies of a data set (e.g., transcription from an interview) and literally cut sections from the transcript that reflect the identified categories. Each cut section is pasted in a notebook or on an index card and filed by the category it represents. (As discussed in Chapter 18, some researchers prefer to use word processors to organize data.)

Computer software programs (e.g., Nudist, Zyindex, Ethnograph, NVivo) facilitate the coding process for large data sets and can help the researcher develop separate files of information that reflect multiple categories. These programs automatically assign codes to similar passages or keywords identified by the investigator. For example, the researcher may program the computer to assign the code “self-care” to every datum that has the term “bathing” in it. Keywords can be selected based on categories that arise from the data set, and the computer can be programmed to assign codes automatically based on a keyword list.

Developing Taxonomies

A taxonomy is a system of categories and relationships. Taxonomies have also been called “typologies” and “mindmaps.”8 Developing a taxonomy represents the next level of organizing information. Taxonomic analysis involves two processes: (1) organizing or grouping similar or related categories into larger categories and (2) identifying differences between sets of subcategories and larger or overarching categories.

Related subcategories are grouped together in the taxonomic process. For example, basic categories such as “whales” and “dogs” belong to the larger category of “animals”; basic categories such as “blocks” and “dolls” belong to the larger category of “toys.” In taxonomy, sets of categories are grouped on the basis of similarities. The investigator must uncover the threads or inclusionary criteria that link categories. Taxonomic analysis is therefore an analytical procedure that results in an organization of categories and that describes their relationships. In a taxonomic analysis, the focus is on identifying the relationship between wholes and parts.

Discovering Underlying Themes

One of the main purposes of analysis in naturalistic research is to understand how each observation or part fits into the whole to make sense of and interpret the layers of meanings and the multiple perspectives that compose the field experience. The major inductive method to accomplish this task is to search for relationships among categories and to reveal the underlying theme or meaning in categories and their components beyond what is immediately visible. Agar suggests that it is from the “simple” process of first establishing topics, categories, and codes that “you begin building a map of the territory that will help you give accounts, and subsequently begin to discuss what ‘those people’ are like.”7

According to Corbin and Strauss,6 the researcher engages in the thinking process of “integrating,” in which he or she finds relationships among categories and further searches for overlap, exclusivity, or hidden meanings among categories. Investigators in grounded theory use the term “theoretical sensitivity” to refer to the researcher's sensitivity and ability to detect and give meanings to data, to go beyond the obvious, and to recognize what is important in the field.6,13

The ethnographer looks for patterns of behavior by examining repeated actions.10 Have14 reminded us that we are not seeking to interpret intrapsychic phenomena; rather, in “ethnomethodology,” we focus on activity as the basis for analysis and meaning. Categories and taxonomies are compared, contrasted, and sorted until a discernable thought or behavioral pattern becomes identifiable and the meaning of the pattern is revealed. As exceptions to rules emerge, variations on themes are detectable. As themes are developed on the basis of abstractions (categories and taxonomies), they are examined in light of ongoing observations. At this point, the investigator may use a literature review or other theoretical concepts to derive an understanding and explanation of the categories based on what has already been investigated or theoretically posited.

These rigorous methods are part of an inductive approach to analysis, and they move the researcher up each loop of the spiral toward understanding and interpretation. Each analytical step from category and taxonomy to thematic identification allows the researcher to uncover the multiple meanings and perspectives of individuals and to develop complex understandings of their experiences and interactions.

In his study of the culture of a nursing home, Savishinsky noted the multiple levels of insights that occur in naturalistic inquiry and the way in which new data can influence previously held notions:

The lives of the residents were absorbing because beneath the deceptively simple style in which they told their stories, there was often depth of passion, or the moral twists of fable, or one small detail which transformed the meaning of all the other details.15

Stage two: formal report preparation

Analysis is a critical and active component of the data collection process. As noted, it begins early in the action process of data collection and continues after the investigator formally leaves the field and has completed collecting information. This final stage of the process is a more formal and analytical step in which the investigator enters into an intensive report preparation effort that furthers the interpretive process. The main objective is to consolidate the investigator's understandings and impressions by writing one or more manuscripts, a final report, or even a book. This reporting effort involves a self-reflective and highly interpretive process, the ease of which often depends on how well the investigator initially organizes and cross-references the voluminous records and field notes. In this more formal analytical stage, the investigator reexamines materials and refines categories, taxonomies, and themes and derives an interpretation. The investigator must also purposely and carefully select quotes and examples to illustrate and highlight each aspect of the refined interpretation. Selections are carefully made to (1) ensure adequate representation of the interpretation or themes the investigator wants to convey, (2) remain true to the voices and experiences being referenced, and (3) depict accurately the context in which the narrative occurred.

In the final interpretation, the investigator moves beyond each datum or piece of information to suggest a deeper understanding of the whole through theory development or an explication of the themes and general principles that emerge from the study of the phenomenon of interest.

Examples of analytical processes

Researchers use the basic analytical processes somewhat differently and often label these activities distinctly. In this section, we examine these similarities and differences in diverse naturalistic approaches. We highlight aspects of the analytical process of grounded theory to demonstrate its highly structured approach in naturalistic inquiry.

Grounded Theory

One of the most formal and systematic analytical approaches is found in grounded theory. The purpose of this approach is to develop theory. Corbin and Strauss6 suggested specific procedures to examine data. Their approach to grounded theory systematizes the inductive incremental analytical process and the continuous interplay between previously collected and analyzed data and new information. The authors labeled their analytical approach the constant comparative method. As information is obtained, it is compared and contrasted with previous information to fit all the pieces inductively together into a larger puzzle. Patterns emerge from the data set and are then coded (placed in a category). Data filing occurs by categorizing and coding. In the constant comparative method, researchers not only search for themes to emerge but also code each piece of raw data according to the categories in which it belongs.

Initially, codes are open, which refers to a “process of breaking down, examining, comparing, conceptualizing and categorizing data.” Axial coding then occurs, which refers to “a set of procedures whereby data are put back together in new ways after open coding by making connections between categories.” Selective coding occurs next, which is the “process of selecting the core category, systematically relating it to other categories.”6 Codes reflect the similarities and differences among themes and continue to test the category system through analysis of each datum and categorical assignment as data are collected. In this way, the analysis is grounded in and emerges from each datum. Theory emerges from the data, is intimately linked to the field reality, and reflects a synthesis of the information gathered.

Grounded theory may be the most systematic and procedure-oriented process in naturalistic inquiry. In various books, Corbin, Strauss, and Glaser—together, individually, and with other authors—systematically walk the researcher through each analytical step of coding and categorizing and use a prescribed language to identify each procedure and task (see References).

Ethnography

Most ethnographic field studies use a range of analytical approaches, based on the specific purpose and nature of the study. The researcher may borrow techniques from grounded theory or use a more general thematic analysis, depending on the particular philosophical stance and analytical orientation of the researcher. To illustrate one way in which a field study analysis may be conducted from beginning to end, we examine DePoy and Archer's study, which was designed to discover the meaning of the quality of life and independence to nursing home residents.16

Because of the limited theory that explained the quality of life and meaning of independence from the perspective of the elderly residents, in their classic study, DePoy and Archer initially chose a qualitative approach to address their research query.16 As the primary data collector, Archer began by examining the “social situation,” or what Spradley and McCurdy10 referred to as the place where the research takes place, of a nursing home in rural New England. Archer recorded her data by separating her observational log into two categories: the physical environment and the human environment. This organizational framework is based on an “environmental competence model” that envisions a person's competence as influencing and, in turn, being influenced by aspects of the physical and social surroundings where behaviors occur.

Archer answered three basic queries with this organizing scheme: (1) What bounds the environment in which the residents live? (2) What physical characteristics does the environment display? and (3) What types of interaction occur within the physical environment? Data were collected and preliminary analyses evolved, determining the similarities between objects to derive descriptive categories. After Archer was able to collect descriptive data about the environment and who was in it, she and DePoy sampled segments of the data set to examine relationships and types of interaction patterns that occurred within the environment. After reading and rereading observational notes, they identified a pattern of the daily schedule followed by both residents and formal providers in the institution. This schedule was conceived as a category of its own, and Archer returned to the field to observe specific times of the day to elaborate or broaden the meaning of this category. For example, she observed morning care, mealtimes, and visiting hours. This set of observations provided greater insight as to the reasons people acted in the way that they did during these times and the meaning of the activity for these individuals. Thus, the initial query was reformulated as, “Why do they do what they do, and what is the meaning of the activity?”

In addition to developing descriptive categories, DePoy and Archer16 used constant comparison14 and taxonomic analysis.4,10 When the constant comparison approach was used, two categories of resident activity emerged from the first set of field notes: self-care and rehabilitation. For example, Archer documented in her field notes an observation of a woman dressing herself with the assistance of an occupational therapist. This datum was initially coded as reflecting two categories of self-care and rehabilitation. The coding occurred as a result of constant comparison in which the observation was compared with previous data in each category and was determined to be sufficiently similar to be included in both.

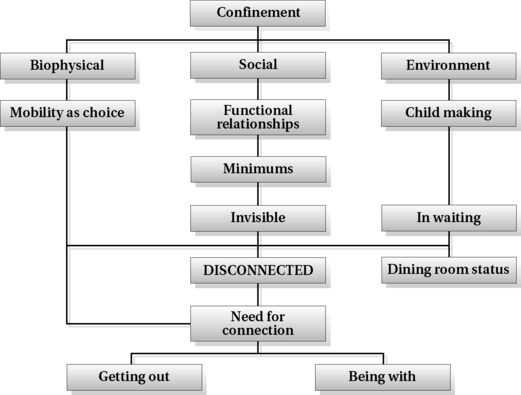

However, as a consequence of comparing new and previous data, discrepancies emerged. This dissonance required reflection and action involving the revision of the category scheme initially developed to depict the nature of the datum. Further along in fieldwork, DePoy and Archer's constant comparisons revealed that the category of “self-care” was characterized by residents conducting their morning routine with assistance in dressing by the occupational therapist. However, other observations revealed that numerous residents were sitting in their beds during the morning self-care time schedule, calling for nursing staff. Did these observations fit into the category of self-care? Because the residents were exercising their right to obtain help from staff, the data could have been coded as self-care. However, because residents appeared to need and be dependent on requested assistance, the data did not seem to fit the concept of independence inherent in the category of self-care. Self-care was thus reconceptualized to reflect a new meaning and was eliminated as a category by itself. The example of the woman dressing with the assistance of the occupational therapist was now coded as “functional relationships,” whereas observations of those remaining in their beds were revised as subcategories of “in waiting” and “confinement” (Figure 20-1).

Figure 20-1 Taxonomy for a study of independence and quality of life in nursing home residents. (From DePoy E, Archer L: Top Geriatr Rehabil 7:64-74, 1992.)

As categories emerged from the data set and became clarified by constant comparison, DePoy and Archer examined relationships among them. Figure 20-1 depicts the simple taxonomy of nursing home experience that inductively emerged from the full data set. As you can see, the lines demonstrate bidirectional connections among categories of findings. For example, the category of “confinement” was divided into three subcategories: biophysical, social, and environmental confinement. Biophysical confinement was both caused by and resulted in mobility choices that were intimately related to the category of “functional relationships” (relationships between residents and staff based on resident need).

Accuracy and rigor in analysis

In naturalistic research a major concern is obtaining an in-depth, rich description and explanation of phenomena. The investigator may not be concerned with the generalizability or external validity of study findings. Rather, the primary focus is obtaining a comprehensive and truthful representation of a particular context. At this point, however, you may be wondering how you, as a consumer of naturalistic research, can trust an investigator's final interpretations as representing scientific “truth.” How can you determine the accuracy or the truth value of an investigator's interpretation of field data? How can you be assured that the experiences of research participants are “accurately” represented in a final report? Of concern is whether the findings of naturalistic inquiry reveal meanings that would have emerged if another researcher would have conducted the same set of interviews, observations, and analytical orientation. That is, do findings reflect the realities of the culture, community, or individuals studied or rather that of the investigator The issue of validity and truth is important.

In naturalistic research the debate continues over how best to construct standards for conducting and evaluating data-gathering and analytical efforts. Denzin and Lincoln, as well as Guba, labeled this as a concern with the trustworthiness or credibility of an account.17,18 Using a rather structured approach, these authors and others have identified a number of strategies by which an investigator can enhance the confidence in the truth of the findings from naturalistic inquiry.8 The concern with credibility of an account or interpretive scheme is similar to the issue of internal validity in experimental-type research. In reading a report involving naturalistic inquiry, the critical reader needs to ask two primary questions: (1) To what extent are the biases and personal perspectives of the investigator identified and considered in the data analysis and interpretation? and (2) What actions has the investigator taken to enhance the credibility of the investigation?

To enhance the accuracy of representation of data and the credibility of interpretation, researchers often use six basic actions (Box 20-2). When reading a published study using naturalistic inquiry, check whether the investigator has used any of these strategies. Let us review each approach to see how it applies to the analytical process. (Also see the discussion of these techniques in Chapter 17.)

Triangulation (Crystallization)

Triangulation, which more recently has been referred to as crystallization, is a basic aspect of data gathering that also shapes the action process of data analysis. In triangulation, one source of information is checked against one or more other types of sources to determine the accuracy of hypothetical understandings and to develop complexity of understanding. For example, one approach to triangulation may involve the comparison of a narrative from an interview with published materials such as a journal. Triangulation enables the investigator to validate a particular finding by examining whether different sources provide convergent information. The term “crystallization” has been applied to reflect the comprehensive analytical understanding that occurs as a result of the comparison of different and diverse sources to explain a phenomenon.

Saturation

Saturation refers to the point at which an investigator has obtained sufficient information from fieldwork. As you may recall, there are several indicators that data collection can be terminated (see Chapter 17). For example, the investigator obtains saturation when the information gathered does not provide additional insights or new understandings. Another indication that saturation has been achieved is when the investigator can guess what a respondent is going to say or do in a particular situation. If saturation is not achieved, the investigator reports only partial information that is preliminary, and a credible and comprehensive account or interpretive schema cannot be developed.

Member Checking

Member checking is a technique in which the investigator checks an assumption or a particular understanding with one or more informants. Affirmation of a particular revelation from a research participant strengthens the credibility of the interpretation and decreases the potential of introducing investigator bias. This technique is often used throughout the data collection process. It is also introduced in the formal stage of analysis to confirm the truth value of specific accounts and investigator impressions.

Reflexivity

In the final report or manuscript, it is important for the researcher to discuss his or her personal biases and assumptions in conducting the study and how these affect the research process. Personal biases are revealed in the course of collecting data and during the active process of reflexivity (self-examination). The investigator purposely engages in a reflexive process to examine his or her perspectives and personal biases to determine how these may have influenced not only what is learned but also how it is learned.

Audit Trail

Another way an investigator can increase truth value is by using an audit trail. Denzin and Lincoln17 suggest that an investigator should leave a path of his or her thinking and coding decisions so that others can review the course of logic and decision making that was followed. The principle here is that the investigator needs to be able to articulate clearly the analytical pathways so that others can agree or disagree or question the decisions that have been made. Remember that research is a critical thinking process in both experimental-type and naturalistic traditions.

Peer Debriefing

Peer debriefing is another strategy that can be used to affirm emerging interpretations. In this approach the investigator purposely involves peers in the analytical process. An investigator may convene a group of peers to review his or her audit trail and emerging findings, or the researcher may ask a peer to code independently a randomly selected set of data. The investigator compares the outcomes with his or her coding scheme. Areas of agreement and disagreement are identified and discussed. Either approach provides an opportunity for the investigator to reflect on other possible competing interpretations of the data. Peer debriefing may occur at various junctures in the analytical process.

Summary

Analysis in naturalistic inquiry has many purposes and strategies. Some researchers seek to generate theory, whereas others aim to reveal and interpret human experiences. Each purpose yields a different analytical strategy. Regardless of study purpose, however, the essential characteristic of the analytical process is that it involves an ongoing inductive and abductive thinking process that is interspersed with the activity of gathering information. Although the analytical process has well-described essential components, each form of naturalistic inquiry approaches this action process differently.

One of the most difficult aspects of naturalistic inquiry is being prepared for the voluminous amount of data that is obtained. Even in a small-scale study, such as a life history of a single individual, the amount of information obtained and the analytic process can initially be overwhelming. The analytical process begins with the simple act of reading and reviewing on multiple occasions the interviews, observational notes, or video images collected. This step begins the thinking process that is essential to the analytic processes of naturalistic inquiry. Through inductive and abductive reasoning, the boundaries of the study become reformulated and defined, and initial descriptive queries are answered. Further data collection efforts are determined by the need to explore the depth and breadth of categories more fully and to answer “why” and “how” type of queries. As data are obtained, they are coded and organized into meaningful categories. The boundaries and meanings of categories are further refined through the process of establishing relationships among categories. Queries that ask “Why?” and “How?” lead to the development of taxonomies. This in turn leads to emergent patterns, meanings, and interpretations of how observations fit into a larger context. Existing theoretical frameworks or constructs in the literature may be brought into the analytical process to refine emerging interpretations or to serve as points of contrast. A refined and final interpretation is usually derived after the investigator exits the field and begins the writing process. Gubrium eloquently summarized the analytical process as follows:

Analysis proceeds incrementally with the aim of making visible the native practice of clarification, from one domain of experience to another, structure upon structure.3

Throughout the analytical process, the investigator must remain flexible and open to constantly challenging his or her emerging interpretive framework.

References

1. Wolcott, H.F. Transforming qualitative data: description, analysis, and interpretation. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 1994.

2. Gubrium, J.F., Holstein, J.A. The new language of qualitative method. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

3. Gubrium, J. Analyzing field reality. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage, 1988.

4. Miles, M.B., Huberman, A.M. The qualitative researcher's companion. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2002.

5. Fetterman, D.L. Ethnography step by step. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2009;94.

6. Corbin, B., Strauss, A. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2007;62.

7. Agar, M.H. The professional stranger: an informal introduction to ethnography, ed 2, San Diego: Academic Press; 1996:105.

8. Northcutt, N., McCoy, D. Interactive qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2004.

9. Wax, M. On misunderstanding verstecken: a reply to Abel. Sociol Soc Res. 1967;51:323–333.

10. Spradley, J.P., McCurdy, D.W. The cultural experience: ethnography in a complex society. Prospect Heights, Ill: Waveland Press, 1988.

11. Gitlin, L.N., Luborsky, M., Schemm, R. Emerging concerns of older stroke patients about assistive devices in rehabilitation. Gerontologist. 1998;38:169–180.

12. Lofland, J., Snow, D., Anderson, L., Lofland, L. Analyzing social settings: a guide to qualitative observation and analysis, ed 3. Belmont, Calif: Wadsworth, 2005.

13. Glaser, B.G. Theoretical sensitivity: advanced in the methodology of grounded theory. Mill Valley, Calif: Sociology Press, 1978.

14. Have, P.T. Understanding qualitative research and ethnomethodology. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2004.

15. Savishinsky, J.S. The ends of time: life and work in a nursing home. New York: Bergen & Garvey, 1991;21.

16. DePoy, E., Archer, L. Quality of life in a nursing home. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 1992;7:64–74.

17. Denzin, N., Lincoln, Y.S. Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage, 2007.

18. Guba, E.G. Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Educ Commun Technol J. 1981;29:75–92.

Assume you are conducting a microethnographic study of the meaning of daily life in an assisted-living facility for elder residents. You decide to use several data collection strategies, such as interviewing residents and family members, observing daily activities, and video-recording staff interactions with residents. The initial purpose of your analysis is to describe daily routines and behaviors of the residents. One analytical strategy may involve counting the number of activities in which residents are engaged, then grouping activities by the categories they represent (e.g., self-care, leisure, social). Another purpose of the analysis is to identify themes that explain the meanings attributed by residents to their daily life in the facility. Analysis will involve an interpretive process to identify statements that reflect core meanings of the experience of assisted living. On the basis of these two analytical steps, suppose you discover that staff relationships are a salient factor in the experiences of residents. To better understand this particular finding, you may add another analytical strategy, such as frame-by-frame video analysis of staff–resident verbal interactions.

Assume you are conducting a microethnographic study of the meaning of daily life in an assisted-living facility for elder residents. You decide to use several data collection strategies, such as interviewing residents and family members, observing daily activities, and video-recording staff interactions with residents. The initial purpose of your analysis is to describe daily routines and behaviors of the residents. One analytical strategy may involve counting the number of activities in which residents are engaged, then grouping activities by the categories they represent (e.g., self-care, leisure, social). Another purpose of the analysis is to identify themes that explain the meanings attributed by residents to their daily life in the facility. Analysis will involve an interpretive process to identify statements that reflect core meanings of the experience of assisted living. On the basis of these two analytical steps, suppose you discover that staff relationships are a salient factor in the experiences of residents. To better understand this particular finding, you may add another analytical strategy, such as frame-by-frame video analysis of staff–resident verbal interactions.