Foundations of Splinting*

1 Define the terms splint and orthosis.

2 Identify the health professionals who may provide splinting services.

3 Appreciate the historical development of splinting as a therapeutic intervention.

4 Apply the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF) to optimize evaluation and treatment for a client.

5 Describe how frame-of-reference approaches are applied to splinting.

6 Familiarize yourself with splint nomenclature of past and present.

7 List the purposes of immobilization (static) splints.

8 List the purposes of mobilization (dynamic) splints.

9 Describe the six splint designs.

10 Define evidence-based practice.

11 Describe the steps involved in evidence-based practice.

12 Cite the hierarchy of evidence for critical appraisals of research.

Determining splint design and fabricating hand splints are extremely important aspects in providing optimal care for persons with upper extremity injuries and functional deficits. Splint fabrication is a combination of science and art. Therapists must apply knowledge of occupation, pathology, physiology, kinesiology, anatomy, psychology, reimbursement systems, and biomechanics to best design splints for persons. In addition, therapists must consider and appreciate the aesthetic value of splints. Beginning splintmakers should be aware that each person is different, requiring a customized approach to splinting. The use of occupation-based and evidence-based approaches to splinting guides a therapist to consider a person’s valued occupations. As a result, those occupations are used as both a means (e.g., as a medium for therapy) and an end to outcomes (e.g., therapeutic goals) [Gray 1998].

Therapists must also develop and use clinical reasoning skills to effectively evaluate and treat clients with upper extremity conditions, and when necessary splint them. This book emphasizes and fosters such skills for beginning splintmakers in general practice areas. After therapists are knowledgeable in the science of splint design and fabrication (including instructing clients on their use and on precautions regarding them, checking for proper fit, and making revisions as deemed appropriate), practical experience is essential for them to become comfortable and competent.

Definition of a Splint

Mosby’s Medical, Nursing, and Allied Health Dictionary (2002) defines a splint as “an orthopedic device for immobilization, restraint, or support of any part of the body” (p. 1618). The text also defines orthosis as “a force system designed to control, correct, or compensate for a bone deformity, deforming forces, or forces absent from the body” (p. 1237).

Today, these health care field terms are often used synonymously. Technically, the term splint refers to a temporary device that is part of a treatment program, whereas the term orthosis refers to a permanent device to replace or substitute for loss of muscle function.

Splints and orthoses not only immobilize but also mobilize, position, and protect a joint or specific body part. Splints range in design and fabrication from simple to complex, depending on the goals established for a particular condition.

Historical Synopsis of Splinting

Reports of primitive splints date back to ancient Egypt [Fess 2002]. Decades ago, blacksmiths and carpenters constructed the first splints. Materials used to make the splints were limited to cloth, wood, leather, and metal [War Department 1944]. Hand splinting became an important aspect of physical rehabilitation during World War II. Survival rates of injured troops dramatically increased because of medical, pharmacologic (e.g., the use of penicillin), and technological advances. During this period, occupational and physical therapists collaborated with orthotic technicians and physicians to provide splints to clients: “Sterling Bunnell, MD, was designated to organize and to oversee hand services at nine army hospitals in the United States” [Rossi 1987, p. 53]. In the mid 1940s, under the guidance of Dr. Bunnell many splints were made and sold commercially. During the 1950s, many children and adults needed splints to assist them in carrying out activities of daily living secondary to poliomyelitis [Rossi 1987]. During this time, orthotists made splints from high-temperature plastics. With the advent of low-temperature thermoplastics in the 1960s, hand splinting became a common practice in clinics.

Today, some therapists and clinics specialize in hand therapy. Hand therapy evolved from a group of therapists in the 1970s who were interested in researching and rehabilitating clients with hand injuries [Daus 1998]. In 1977, this group of therapy specialists established the American Society for Hand Therapy (ASHT). In 1991, the first certification examination in hand therapy was given. Those therapists who pass the certification examination are credentialed as certified hand therapists (CHTs).

Specialized organizations (e.g., American Society for Surgery of the Hand and ASHT) influence the practice, research, and education of upper extremity splinting [Fess et al. 2005]. For example, the ASHT Splint Classification System offered a uniform nomenclature in the area of splinting [Bailey et al. 1992].

Splintmakers

A variety of health care professionals design and fabricate splints. Occupational therapists (OTs) constitute a large population of health care providers whose services include splint design and fabrication. Certified occupational therapy assistants (COTAs) also provide splint services. Along with OTs and COTAs, physical therapists (PTs) specializing in hand rehabilitation often fabricate splints for their clients who have hand injuries. PTs are frequently involved in providing splints for the lower extremities. In addition, certified orthotists (COs) are trained and skilled in the design, construction, and fitting of braces and orthoses prescribed by physicians. Dentists frequently fabricate orthoses to address selective dental problems. Occasionally, nurses who have had special training fabricate splints.

Splint design must be based on scientific principles. A given diagnosis does not specify the splint the clinician will make. Splint fabrication often requires creative problem solving. Such factors as a client’s occupational needs and interests influence a splint design, even among clients who have common diagnoses. Health care professionals who make splints must allow themselves to be creative and take calculated risks. Splintmaking requires practice for the clinician to be at ease with the design and fabrication process. Students or therapists beginning to design and fabricate splints should be aware of personal expectations and realize that their skills will likely evolve with practice. Therapists with experience in splinting tend to be more efficient with time and materials than novice students and therapists.

Occupational Therapy Theories, Models, and Frame-of-Reference Approaches for Splinting

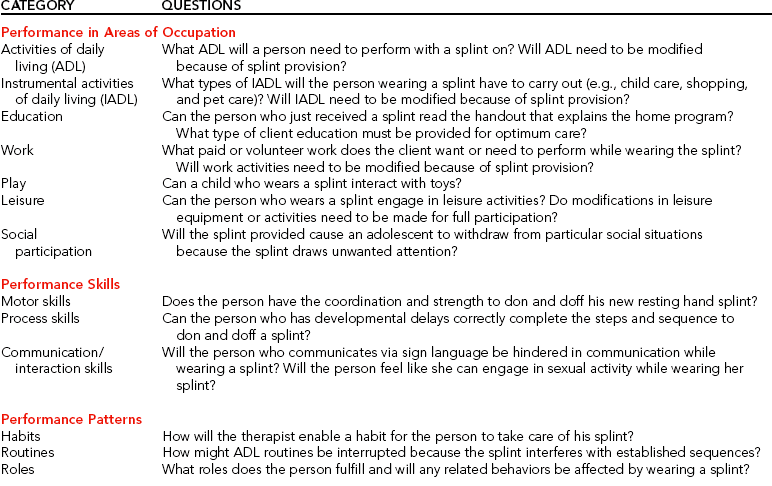

The OTPF outlines the occupational therapy process of evaluation and intervention and highlights the emphasis on the use of occupation [AOTA 2002]. Performance areas of occupation as specified in the framework include the following: activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), education, work, play, leisure, and social participation. Performance areas of occupation place demands on a person’s performance skills (i.e., motor skills, process skills, and communication/interaction skills). Therapists must consider the influence of performance patterns on occupation. Such patterns include habits, routines, and roles. Contexts affect occupational participation. Contexts include cultural, physical, social, personal, spiritual, temporal, and virtual dimensions. The engagement in an occupation involves activity demands placed on the individual. Activity demands include objects used and their properties, space demands, social demands, sequencing and timing, and required actions, body functions, and body structures. Client factors relate to a person’s body functions and body structures.Table 1-1 provides examples of how the framework assists one in thinking about splint provision to a client.

Table 1-1

Examples* of the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework and Splint Provision

*Examples are inclusive, not exclusive.

The practice of occupational therapy is guided by conceptual systems [Pedretti 1996]. One such conceptual system is the Occupational Performance Model, which consists of performance areas, components, and contexts. A therapist using the Occupational Performance Model may influence a client’s performance area or component while considering the context in which the person must operate. The therapist is guided by several treatment approaches in providing assessment and treatment. The therapist may use the biomechanical, sensorimotor, and rehabilitative approaches. The biomechanical approach uses biomechanical principles of kinetics and forces acting on the body. Sensorimotor approaches are used to inhibit or facilitate normal motor responses in persons whose central nervous systems have been damaged. The rehabilitation approach focuses on abilities rather than disabilities and facilitates returning persons to maximal function using their capabilities [Pedretti 1996]. (See Self-Quiz 1-1.)

Each approach can incorporate splinting as a treatment intervention, depending on the rationale for splint provision. For example, if a person wears a tenodesis splint to recreate grasp and release to maximize function in activities of daily living, the therapist is using the rehabilitation approach [Hill and Presperin 1986]. If the therapist is using the biomechanical approach, a dynamic (mobilization) hand splint may be chosen to apply kinetic forces to the person’s body. If the therapist chooses a sensorimotor approach, an antispasticity splint may be used to inhibit or reduce tone.

Pierce’s notions [Pierce 2003] of contextual and subjective dimensions of occupation are powerful concepts for therapists who appropriately incorporate splinting into a client’s care plan. Understanding how a splint affects a client’s occupational engagement and participation are salient in terms of meeting the client’s needs and goals, which may result in an increased probability of compliance. Contextual dimensions include spatial, temporal, and sociocultural contexts [Pierce 2003]. Subjective dimensions include restoration, pleasure, and productivity.Box 1-1 explicates both contextual and subjective dimensions of occupation. In Chapter 3, Pierce’s framework is used to structure questions for a client interview.

Splint Categorization

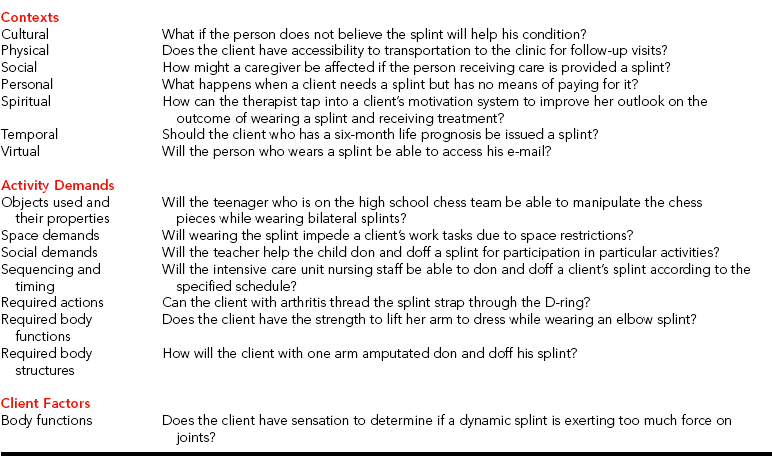

According to the ASHT [1992], there are six splint classification divisions: (1) identification of articular or nonarticular, (2) location, (3) direction, (4) purpose, (5) type, and (6) total number of joints (Figure 1-1).

Figure 1-1 Expanded splint classification system division. [From Fess EE, Gettle KS, Philips CA, Janson JR (2005). Hand and Upper Extremity Splinting: Principles and Methods, Third Edition. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby.]

Articular/Nonarticular

The first element of the ASHT classification indicates whether or not a splint affects articular structures. Articular splints use three-point pressure systems “to affect a joint or joints by immobilizing, mobilizing, restricting, or transmitting torque” [Fess 2005, p. 124]. Most splints are articular, and the term articular is often not specified in the technical name of the splint.

Nonarticular splints use a two-point pressure force to stabilize or immobilize a body segment [Fess et al. 2005]. Thus, the term nonarticular should always be included in the name of the splint. Examples of nonarticular splints include those that affect the long bones of the body (e.g., humerus).

Location

Splints, whether articular or nonarticular, are classified further according to the location of primary anatomic parts included in the splint. For example, articular splints will include a joint name in the splint [e.g., elbow, thumb metacarpal (MP), index finger proximal interphalangeal (PIP)]. Nonarticular splints are associated with one of the long bones (e.g., ulna, humerus, radius).

Direction

Direction classifications are applicable to articular splints only. Because all nonarticular splints work in the same manner, the direction does not need to be specified. Direction is the primary kinematic function of splints. Such terms as flexion, extension, and opposition are used to classify splints according to direction. For example, a splint designed to flex the PIP joints of index, middle, ring, and small fingers would be named an index–small-finger PIP flexion splint.

Purpose

The fourth element in the ASHT classification system is purpose. There are four purposes of splints: (1) mobilization, (2) immobilization, (3) restriction, and (4) torque transmission. The purpose of the splint indicates how the splint works. Examples include the following:

• Mobilization: Wrist/finger-MP extension mobilization splint.

• Immobilization: Elbow immobilization splint.

• Restriction: Elbow extension restriction splint.

• Torque transmission: Finger PIP extension torque transmission splint, type 1 (2). (The number in parentheses indicates the total number of joints incorporated into the splint.)

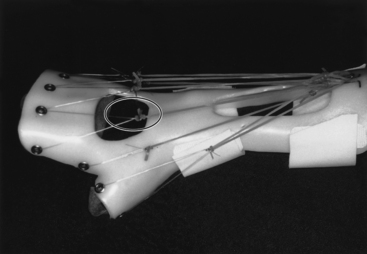

Mobilization splints are designed to move or mobilize primary and secondary joints. Immobilization splints are designed to immobilize primary and secondary joints. Restrictive splints “limit a specific aspect of joint range of motion for the primary joints” [ASHT 1992, p. 9]. Torque transmission splints’ purposes are to “(1) create motion of primary joints situated beyond the boundaries of the splint itself or (2) harness secondary ‘driver’ joint(s) to create motion of primary joints that may be situated longitudinally or transversely to the ‘driver’ joint(s)” [Fess et al. 2005, p. 126]. Torque transmission splints, illustrated inFigure 1-2, are also referred to as exercise splints.

Figure 1-2 Torque transmission splints may create motion of primary joints situated longitudinally (A) or transversely (B) according to secondary joints. [From Fess EE, Gettle KS, Philips CA, Janson JR (2005). Hand and Upper Extremity Splinting: Principles and Methods, Third Edition. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby.]

Type

The classification of splint type specifies the secondary joints included in the splint. Secondary joints are often incorporated into the splint design to affect joints that are proximal, distal, or adjacent to the primary joint. There are 10 joints that comprise the upper extremity: shoulder, elbow, forearm, wrist, finger MP, finger PIP, finger distal interphalangeal (DIP), thumb carpometacarpal (CMC), thumb metacarpophalangeal (MP), and thumb interphalangeal (IP) levels. Only joint levels are counted, not the number of individual joints. For example, if the wrist joint and multiple finger PIP joints are included as secondary joints in a splint the type is defined as 2 (PIP joints account for one level and the wrist joint accounts for another level, thus totaling two secondary joint levels). The technical name for a splint that flexes the MP joints of the index, middle, ring, and small fingers and incorporates the wrist and PIP joints is an index–small-finger MP flexion mobilization splint, type 2. If no secondary joints are included in the splint design, the joint level is type 0.

Total Number of Joints

The final ASHT classification level is the total number of individual joints incorporated into the splint design. The number of total joints incorporated in the splint follows the type indication. For example, if an elbow splint includes the wrist and MPs as secondary joints the splint would be called an elbow flexion immobilization splint, type 2 (3). The number in parentheses indicates the total number of joints incorporated into the splint.

Splint Designs

In the past, splints were categorized as static or dynamic. This classification system has its problems and controversies. However, in some clinics ASHT splint terminology is not often used. Therefore, therapists must be familiar with the ASHT classification system as well as other commonly used nomenclature. Static splints have no movable parts [Cailliet 1994]. In addition, static splints place tissues in a stress-free position to enhance healing and to minimize friction [Schultz-Johnson 1996]. Dynamic splints have one or more movable parts [Malick 1982] and are synonymous with splints that employ elastics, springs, and wire, as well as with multipart splints.

The purpose of a splint as a therapeutic intervention assists the therapist in determining its design. Splinting design classifications include (1) static, (2) serial static, (3) dropout, (4) dynamic, and (5) static-progressive [Schultz-Johnson 1996].

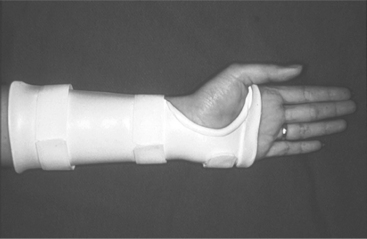

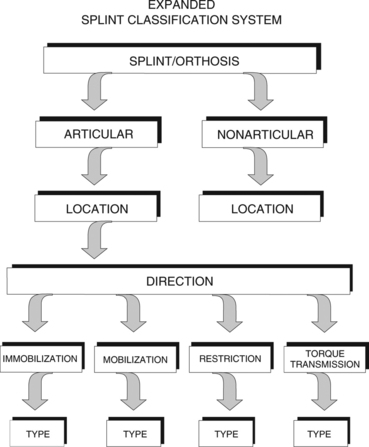

A static splint (Figure 1-3) can maintain a position to hold anatomical structures at the end of available range of motion, thus exerting a mobilizing effect on a joint [Schultz-Johnson 1996]. For example, a therapist fabricates a splint to position the wrist in maximum tolerated extension to increase extension of a stiff wrist. Because the splint positions the shortened wrist flexors at maximum length and holds them there, the tissue remodels in a lengthened form [Schultz-Johnson 1996].

Figure 1-3 Static immobilization splint. This static splint immobilizes the thumb, fingers, and wrist.

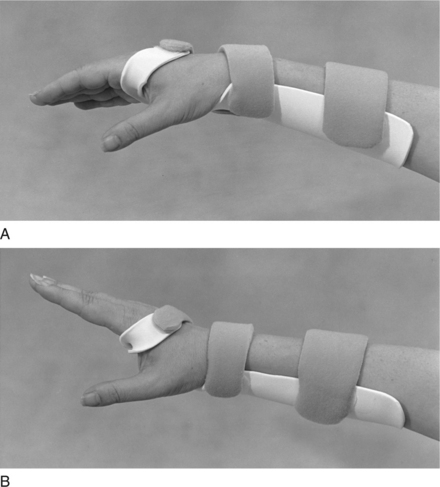

Serial static splinting (Figure 1-4) requires the remolding of a static splint. The serial static splint holds the joint or series of joints at the limit of tolerable range, thus promoting tissue remodeling. As the tissue remodels, the joint gains range and the clinician remolds the splint to once again place the joint at end range comfortably. Schultz-Johnson [1996] pointed out that circumferential splints that are nonremovable require no cooperation from those who wear them, except to leave them on.

Figure 1-4 Serial static splints (A and B). The therapist intermittently remolds the splint as the client gains wrist extension motion.

A dropout splint (Figure 1-5) allows motion in one direction while blocking motion in another [ASHT 1992]. This type of splint may help a person regain lost range of motion while preventing poor posture. For example, a splint may be designed to enhance wrist extension while blocking wrist flexion [Schultz-Johnson 1996].

Figure 1-5 Dropout splint. A dorsal–forearm-based dynamic extension splint immobilizes the wrist and rests all fingers in a neutral position. A volar block permits only the predetermined MCP joint flexion. [From Evans RB, Burkhalter WE (1986). A study of the dynamic anatomy of extensor tendons and implications for treatment. Journal of Hand Surgery 11A:774.]

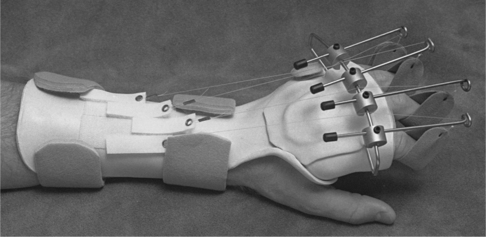

Elastic tension dynamic (mobilization) splints (Figure 1-6) have self-adjusting or elastic components, which may include wire, rubber bands, or springs [Fess and Philips 1987]. A splint that applies an elastic tension force to straighten an index finger PIP flexion contracture exemplifies an elastic tension/traction dynamic (mobilization) splint.

Figure 1-6 Elastic tension splint. This splint for radial nerve palsy has elastic rubber bands and inelastic filament traction. [Courtesy of Dominique Thomas, RPT, MCMK, Saint Martin Duriage, France, from Fess EE, Gettle KS, Philips CA, Janson JR (2005). Hand and Upper Extremity Splinting: Principles and Methods, Third Edition. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby.]

Static progressive splints (Figure 1-7) are types of dynamic (mobilization) splints. They incorporate the use of inelastic components such as hook-and-loop tapes, outrigger line, progressive hinges, turnbuckles, and screws. The splint design incorporates the use of inelastic components to allow the client to adjust the line of tension so as to prevent overstressing of tissue [Schultz-Johnson 1995]. Chapter 11 more thoroughly addresses mobilization and torque transmission (dynamic) splints.

Figure 1-7 Static progressive splint. A splint to increase PIP extension uses hook-and-loop mechanisms for adjustable tension.

Many possibilities exist for splint design and fabrication. A therapist’s creativity and skills are necessary for determining the best splint design. Therapists must stay updated on splinting techniques and materials, which change rapidly. Reading professional literature and manufacturers’ technical information helps therapists maintain knowledge about materials and techniques. A personal collection of reference books is also beneficial, and continuing-education courses provide ongoing updates on the latest theories and techniques.

Evidence-Based Practice and Splinting

Calls for evidence-based practice have stemmed from medicine but have affected all of health care delivery, including splinting [Jansen 2002]. Sackett and colleagues [1996, pp. 71-72] defined evidence-based practice as “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual clients. The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research.”

The aim of applying evidence-based practice is to “ensure that the interventions used are the most effective and the safest options” [Taylor 1997, p. 470]. Essentially, therapists apply the research process during practice. This includes (1) formulating a clear question based on a client’s problem, (2) searching the literature for pertinent research articles, (3) critically appraising the evidence for its validity and usefulness, and (4) implementing useful findings to the client case. Evidence-based practice is not about finding articles to support what a therapist does. Rather, it is reviewing a body of literature to guide the therapist in selecting the most appropriate assessment or treatment for an individual client.

Sackett et al. [1996] and Law [2002] outlined several myths of evidence-based practice and described the reality of each myth (Table 1-2). A misconception exists that evidence-based practice is impossible to practice or that it already exists. Although we know that keeping current on all health care literature is impossible, few practitioners consistently review research findings related to their specific practice. Instead, many practitioners rely on their training or clinical experience to guide clinical decision making. Novel clinical situations present a need for evidence-based practice.

Table 1-2

Evidence-Based Practice Myths and Realities

| MYTH | REALITY |

| Evidence-based practice exists | Practitioners spend too little time examining current research findings |

| Evidence-based practice is difficult to integrate into practice | Evidence-based practice can be implemented by busy practitioners |

| Evidence-based practice is a “cookie cutter” approach | Evidence-based practice requires extensive clinical experience |

| Evidence-based practice is focused on decreasing costs | Evidence-based practice emphasizes the best clinical evidence for individual clients |

Some argue that evidence-based practice leads to a “cookie cutter” approach to clinical care. Evidence-based practice involves a critical appraisal of relevant research findings. It is not a top-down approach. Rather, it adopts a bottom-up approach that integrates external evidence with one’s clinical experience and client choice. After reviewing the findings, practitioners must use clinical judgment to determine if, why, and how they will apply findings to an individual client case. Thus, evidence-based practice is not a one-size-fits-all approach because all client cases are different.

Evidence-based practice is not intended to be a mechanism whereby all clinical decisions must be backed by a random controlled trial. Rather, the intent is to address efficacy and safety using the best current evidence to guide intervention for a client in the safest way possible. It is important to realize that efficacy and safety do not always result in a cost decrease.

Important to evidence-based practice is the ability of practitioners to appraise the quality of the evidence available. A hierarchy of evidence is based on the certainty of causation and the need to control bias.Table 1-3 [Lloyd-Smith 1997] shows this hierarchy. The highest quality (gold standard) of evidence is the meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Next in the hierarchy is one study employing an individual random controlled trial. A well-designed nonrandomized study is next in the hierarchy, followed by quasi-experimental designs and nonexperimental descriptive studies. Last in the hierarchy is expert practitioner opinion.Box 1-2 presents a list of appraisal questions used to evaluate quantitative and qualitative research results.

Table 1-3

| STEP | DESCRIPTION |

| 1A | Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials |

| 1B | One individual randomized controlled trial |

| 2A | One well-designed nonrandomized controlled study |

| 2B | Well-designed quasi-experimental study |

| 3 | Nonexperimental descriptive studies (comparative/case studies) |

| 4 | Respectable opinion |

Throughout this book, the authors made an explicit effort to present the research relevant to each chapter topic. Note that the evidence is limited to the timing of this publication. Students and practitioners should review literature to determine applicability of contemporary publications. The Cochrane Library, CINAHL (Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature), MEDLINE, EMBASE (comprehensive pharmacological and biomedical database), OT Index, HAPI (Health and Psychosocial Instruments), ASSIA (Applied Social Sciences Index of Abstracts), and HealthStar are useful databases to access during searches for research.

1. What health care professionals provide splinting services to persons?

2. What are the three therapeutic approaches used in physical dysfunction? Give an example of how splinting could be used as a therapeutic intervention for each of the three approaches.

3. How might the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework assist a therapist in splint provision?

4. What are the six divisions of the ASHT splint classification system?

5. What purposes might a splint be used for as part of the therapeutic regimen?

6. What is evidence-based practice? How can it be applied to splint intervention?

7. In evidence-based practice, what is the hierarchy of evidence?

References

American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2002;56:609–639.

American Society of Hand Therapists. Splint classification system. Garner, NC: The American Society of Hand Therapists, 1992.

Bailey, J, Cannon, N, Colditz, J, Fess, E, Gettle, K, DeMott, L, et al. Splint Classification System. Chicago: American Society of Hand Therapists, 1992.

Cailliet, R. Hand Pain and Impairment, Fourth Edition. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1994.

Daus, C. Helping hands: A look at the progression of hand therapy over the past 20 years. Rehab Management. 1998:64–68.

Fess, EE. A history of splinting: To understand the present, view the past. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2002;15:97–132.

Fess, EE, Gettle, KS, Philips, CA, Janson, JR. A history of splinting. In: Fess EE, Gettle KS, Philips CA, Janson JR, eds. Hand and Upper Extremity Splinting: Principles and Methods. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2005:3–43.

Fess, EE, Philips, CA. Hand Splinting Principles and Methods, Second Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, 1987.

Gray, JM. Putting occupation into practice: Occupation as ends, occupation as means. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1998;52(5):354–364.

Hill, J, Presperin, J. Deformity control. In: Intagliata S, ed. Spinal Cord Injury: A Guide to Functional Outcomes in Occupational Therapy. Rockville, MD: Aspen Publishers; 1986:49–81.

Jansen, CWS. Outcomes, treatment effectiveness, efficacy, and evidence-based practice. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2002;15:136–143.

Law, M. Introduction to evidence based practice. In: Law M, ed. Evidence-based Rehabilitation. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 2002:3–12.

Lloyd-Smith, W. Evidence-based practice and occupational therapy. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1997;60:474–478.

Malick, MH. Manual on Dynamic Hand Splinting with Thermoplastic Material, Second Edition. Pittsburgh: Harmarville Rehabilitation Center, 1982.

Pedretti, LW. Occupational performance: A model for practice in physical dysfunction. In: Pedretti LW, ed. Occupational Therapy: Practice Skills for Physical Dysfunction. Fourth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996:3–12.

Pierce, DE. Occupation by Design: Building Therapeutic Power. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 2003.

Rossi, J. Concepts and current trends in hand splinting. Occupational Therapy in Health Care. 1987;4:53–68.

Sackett, DL, Rosenberg, WM, Gray, JA, Haynes, RB, Richardson, WS. Evidence-based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. British Medical Journal. 1996;312:71–72.

Schultz-Johnson, K. Splinting the wrist: Mobilization and protection. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1996;9(2):165–177.

Taylor, MC. What is evidenced-based practice? British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1997;60:470–474.

War Department. Bandaging and Splinting. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1944.