Splinting Processes, Tools, and Techniques

1 Identify splint material properties.

2 Recognize tools commonly used in the splinting process.

3 Identify various methods to optimally prepare a client for splinting.

4 Explain the process of cutting and molding a splint.

5 List common splinting items that should be available to a therapist for splint provision.

6 List the advantages and disadvantages of using prefabricated splints.

7 Explain the reasons for selecting a soft splint over a prefabricated splint.

8 Explain three ways to adjust a static progressive force on prefabricated splints.

9 Relate an example of how a person’s occupational performance might influence prefabricated splint selection.

10 Summarize the American Occupational Therapy Association’s (AOTA’s) position on occupational therapists’ use of physical agent modalities (PAMs).

11 Define conduction and convection.

12 Describe the indications, contraindications, and safety precautions for the use of PAMs in preparation for splinting.

Splinting requires knowledge of a variety of processes, tools, and techniques. This chapter reviews commonly used processes, tools, and techniques related to splinting. Splints and their purposes needed to address a variety of clients who require custom-made or prefabricated splint intervention are discussed. This chapter also outlines how PAMs may be used to prepare a client for optimal positioning during the splinting process.

Thermoplastic Splinting Materials

Low-temperature thermoplastic (LTT) materials are the most commonly used to fabricate splints. The materials are considered “low temperature” because they soften in water heated between 135° and 180°F and the therapist can usually safely place them directly against a person’s skin while the plastic is still moldable. These compare to high-temperature thermoplastics that become soft when warmed to greater than 250°F and cannot touch a person’s skin while moldable without causing a thermal injury. When LTT is heated, it becomes pliable, and then hardens to its original rigidity after cooling. The first commonly available low-temperature thermoplastic material was Orthoplast. Currently, many types of thermoplastic materials are available from several companies. Types of materials used in clinics vary on the basis of patient population, diagnoses, therapists’ preferences, and availability.

In addition to splint use, LTT material is commonly used to adapt devices for improving function. For example, thermoplastic material may be heated and wrapped around pens, handles, utensils, and other tools to build up the circumference and decrease the required range of motion needed to use such items.

Decisions regarding the best type of thermoplastic material to use for splint fabrication must be made. Decisions are based on such factors as cost, properties of the thermoplastic material, familiarity with splinting materials, and therapeutic goals. One type of thermoplastic material is not the best choice for every type or size of splint. If a therapist has not had experience with a particular type of thermoplastic material, it is beneficial to read the manufacturer’s technical literature describing the material’s content and properties. Therapists should practice using new materials before fabricating splints on clients.

Thermoplastic Material Content and Properties

Thermoplastic materials are elastic, plastic, a combination of plastic and rubberlike, and rubberlike [North Coast Medical 2006]. Thermoplastic materials that are elastic based have some amount of memory. (Memory is addressed in the properties discussion of this section.) Typically, elastic thermoplastic has a coating to prevent the material from adhering to itself. (Most thermoplastics have a nonstick coating, but there are a few that specify they do not.) Elastic materials have a longer working time than other types of materials and tend to shrink during the cooling phase.

Thermoplastics with a high plastic content tend to be drapable and have a low resistance to stretch. Plastic-based materials are often used because they result in a highly conforming splint. Such plastic requires great skill in handling the material (e.g., avoiding fingerprints and stretch) during heating, cutting, moving, positioning, draping, and molding. Thus, for novice splinters positioning the client in a gravity-assisted position is best to prevent overstretching of the material.

Thermoplastic materials described as rubbery or rubberlike tend to be more resistant to stretching and fingerprinting. These materials are less conforming than their drapier plastic counterparts. Therapists should not confuse resistance to stretch during the molding process with the rigidity of the splint upon completion. Materials that are quite drapey become extremely rigid when cooled and set, and the opposite is also true. In addition, the more contours a splint contains the more rigid it will be.

Some LTT materials are engineered to include an antimicrobial protection. Splints can create a moist surface on the skin where mold and mildew can form [Sammons et al. 2006]. When skin cells and perspiration remain in a relatively oxygen-free environment for hours at a time, it is conducive to microbe growth and results in odor. Daily isopropyl alcohol cleansing of the inside surface of the splint will effectively combat this problem. Splinting materials containing the antimicrobial protection offer a defense against microorganisms. The antimicrobial protection does not wash or peel off.

Each type of thermoplastic material has unique properties [Lee 1995] categorized by handling and performance characteristics. Handling characteristics refer to the thermoplastic material properties when heated and softened, and performance characteristics refer to the thermoplastic material properties after the material has cooled and hardened.

Handling Characteristics

Memory is a property that describes a material’s ability to return to its preheated (original) shape, size, and thickness when reheated. The property ranges from 100% to little or no memory capabilities [North Coast Medical 1999]. Materials with 100% memory will return to their original size and thickness when reheated. Materials with little to no memory will not recover their original thickness and size when reheated.

Most materials with memory turn translucent (clear) during heating. Using the translucent quality as an indicator, the therapist can easily determine that the material is adequately heated and can prevent over- or underheating. The ability to see through the material also assists the therapist to properly position and contour the material on the client.

Memory allows therapists to reheat and reshape splints several times without the material stretching excessively. Materials with memory must be constantly molded throughout the cooling process to sustain maximal conformability to persons. Novice or inexperienced therapists who wish to correct errors in a poorly molded splint frequently use materials with memory. Material with memory will accommodate the need to redo or revise a splint multiple times while using the same piece of material over and over. LTT material with memory is often used to make splints for clients who have high tone or stiff joints, because the memory allows therapists to adjust or serially splint a joint(s) into a different position. Clinicians use a serial splinting approach when they intermittently remold to a person’s limb to accommodate changes in range of motion.

Materials with memory may pose problems when one is attempting to make fine adjustments. For example, spot heating a small portion may inadvertently change the entire splint because of shrinkage. Therapists must carefully control duration of heat exposure. It may be best in these situations to either reimmerse the entire splint in water and repeat the molding process or prevent the problem and select a different type of LTT material.

Drapability

Drapability is the degree of ease with which a material conforms to the underlying shape without manual assistance. The degree of drapability varies among different types of material. The duration of heating is important. The longer the material heats the softer it becomes and the more vulnerable it becomes to gravity and stretch. When a material with drapability is placed on a surface, gravity assists the material in draping and contouring to the underlying surface. Material exhibiting drapability must be handled with care after heating. A therapist should avoid holding the plastic in a manner in which gravity affects the plastic and results in a stretched, thin piece of plastic. Therefore, this type of plastic is best positioned on a clean countertop during cutting. Material with high drapability is difficult to use for large splints and is most successful on a cooperative person who can place the body part in a gravity-assisted position.

Thermoplastic materials with high drapability may be more difficult for beginning splintmakers because the materials must be handled gently and often novice splinters handle the material too aggressively. Successful molding requires therapists to refrain from pushing the material during shaping. Instead, the material should be lightly stroked into place. Light touch and constant movement of therapists’ hands will result in splints that are cosmetically appealing. Materials with low drapability require firm pressure during the molding process. Therefore, persons with painful joints or soft-tissue damage will better tolerate materials with high drapability.

Elasticity

Elasticity is a material’s resistance to stretch and its tendency to return to its original shape after stretch. Materials with memory have a slight tendency to rebound to their original shapes during molding. Materials with a high resistance to stretch can be worked more aggressively than materials that stretch easily. As a result, resistance to stretch is a helpful property when one is working with uncooperative persons, those with high tone, or when one splint includes multiple areas (i.e., forearm, wrist, ulnar border of hand, and thumb in one splint). Materials with little elasticity will stretch easily and become thin. Therefore, light touch must be used.

Bonding

Self-bonding or self-adherence is the degree to which material will stick to itself when properly heated. Some materials are coated; others are not. Materials that are coated always require surface preparation with a bonding agent or solvent. Self-bonding (uncoated) materials may not require surface preparation, but some thermoplastic materials have a coating that must be removed for bonding to occur. Coated materials tack at the edges because the coating covers only the surface and not the edges.

Often, the tacked edges can be pried apart after the material is completely cool. If a coated material is stretched, it becomes tackier and is more likely to bond. When heating self-bonding material, the therapist must take care that the material does not overlap on itself during the heating or draping process. If the material overlaps, it will stick to itself. Noncoated materials may adhere to paper towels, towels, bandages, and even the hair on a client’s extremity! Thus, it may be necessary to apply an oil-based lotion to the client’s extremity. To facilitate the therapist’s handling of the material, wetting the hands and scissors with water or lotion can prevent sticking.

All thermoplastic material, whether coated or uncoated, forms stronger bonds if surfaces are prepared with a solvent or bonding agent (which removes the coating from the material). A bonding agent or solvent is a chemical that can be brushed onto both pieces of the softened plastic to be bonded. In some cases, therapists roughen the two surfaces that will have contact with each other. This procedure, called scoring, can be carefully done with the end of a scissors, an awl, or a utility knife. After surfaces have been scored, they are softened, brushed with a bonding agent, and adhered together. Self-adherence is an important characteristic for mobilization splinting when one must secure outriggers to splint bases (see Chapter 11) and when the plastic must attach to itself to provide support—for example, when wrapping around the thumb as in a thumb spica splint (see Chapter 8).

Self-finishing Edges

A self-finishing edge is a handling characteristic that allows any cut edge to seal and leave a smooth rounded surface if the material is cut when warm. This handling characteristic saves time for therapists because they do not have to manually roll or smooth the edges.

Other Considerations

Other handling characteristics to be considered are heating time, working time, and shrinkage. The time required to heat thermoplastic materials to a working temperature should be monitored closely because material left too long in hot water may become excessively soft and stretchy. Therapists should be cognizant of the temperature the material holds before applying it to a person’s skin to prevent a burn or discomfort. After material that is  inch thick is sufficiently heated, it is usually pliable for approximately 3 to 5 minutes (S. Berger, personal communication, 1995). Some materials will allow up to 4 to 6 minutes of working time. Materials thinner than

inch thick is sufficiently heated, it is usually pliable for approximately 3 to 5 minutes (S. Berger, personal communication, 1995). Some materials will allow up to 4 to 6 minutes of working time. Materials thinner than  inch and those that are perforated heat and cool more quickly.

inch and those that are perforated heat and cool more quickly.

Shrinkage is an important consideration when therapists are properly fitting any splint, but particularly with a circumferential design. Plastics shrink slightly as they cool. During the molding and cooling time, precautions should be taken to avoid a shrinkage-induced problem such as difficulty removing a thumb or finger from a circumferential component of a splint.

Performance Characteristics

Conformability is a performance characteristic that refers to the ability of thermoplastic material to fit intimately into contoured areas. Material that is easily draped and has a high degree of conformability can pick up fingerprints and crease marks (as well as therapists’ fingerprints). Splints that are intimately conformed to persons are more comfortable because they distribute pressure best and reduce the likelihood of the splint migrating on the extremity.

Flexibility

A thermoplastic material with a high degree of flexibility can take stresses repeatedly. Flexibility is an important characteristic for circumferential splints because these splints must be pulled open for application and removal.

Durability

Durability is the length of time splint material will last. Rubber-based materials are more likely to become brittle with age.

Rigidity

Materials that have a high degree of rigidity are strong and resistant to repeated stress. Rigidity is especially important when therapists make medium to large splints (such as splints for elbows or forearms). Large splints require rigid material to support the weight at larger joints. In smaller splints, rigidity is important if the plastic must stabilize a joint. Rigidity can be enhanced by contouring a splint intimately to the underlying body shape [Wilton 1997]. Most LTT materials cannot tolerate the repeated forces involved in weight bearing on a splint, as in foot orthoses. Most foot orthoses will have fatigue cracks within a few weeks [McKee and Morgan 1998].

Perforations

Theoretically, perforations in material allow for air exchange to the underlying skin. Various perforation patterns are available (e.g., mini-, maxi-, and micro-perforated) [PSR 2006]. Perforated materials are also designed to reduce the weight of splints. Several precautions must be taken if one is working with perforated materials [Wilton 1997]. Perforated material should not be stretched because stretching will enlarge the holes in the plastic and thereby decrease its strength and pressure distribution. When cutting a pattern out of perforated material, therapists should attempt to cut between the perforations to prevent uneven or sharp edges. If this cannot be avoided, the edges of the splint should be smoothed.

Finish, Colors, and Thickness

Finish refers to the texture of the end product. Some thermoplastics have a smooth finish, whereas others have a grainy texture. Generally, coated materials are easier to keep clean because the coating resists soiling [McKee and Morgan 1998].

The color of the thermoplastic material may affect a person’s acceptance and satisfaction with the splint and compliance with the wearing schedule. Darker-colored splints tend to show less soiling and appear cleaner than white splints. Brightly colored splints tend to be popular with children and youth. Colored materials may be used to help a person with unilateral neglect call attention to one side of the body [McKee and Morgan 1998]. In addition, colored splints are easily seen and therefore useful in preventing loss in institutional settings. For example, it is easier to see a blue splint in white bed linen than to see a white splint in white bed linen.

A common thickness for thermoplastic material is  inch. However, if the weight of the entire splint is a concern a thinner plastic may be used—reducing the bulkiness of the splint and possibly increasing the person’s comfort and improving compliance with the wearing schedule. Some thermoplastic materials are available in thicknesses of 1/16, 3/32, and 3/16 inch. Thinner thermoplastic materials are commonly used for small splints and for arthritis and pediatric splints, whereas the 3/16-inch thickness is commonly used for lower extremity splints and fracture braces [Melvin 1989, Sammons et al. 2006]. Therapists should keep in mind that plastics thinner than

inch. However, if the weight of the entire splint is a concern a thinner plastic may be used—reducing the bulkiness of the splint and possibly increasing the person’s comfort and improving compliance with the wearing schedule. Some thermoplastic materials are available in thicknesses of 1/16, 3/32, and 3/16 inch. Thinner thermoplastic materials are commonly used for small splints and for arthritis and pediatric splints, whereas the 3/16-inch thickness is commonly used for lower extremity splints and fracture braces [Melvin 1989, Sammons et al. 2006]. Therapists should keep in mind that plastics thinner than  inch will soften and harden more quickly than thicker materials. Therefore, therapists who are novices in splinting may find it easier to splint with

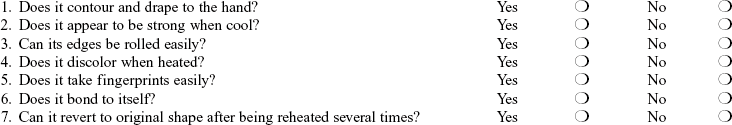

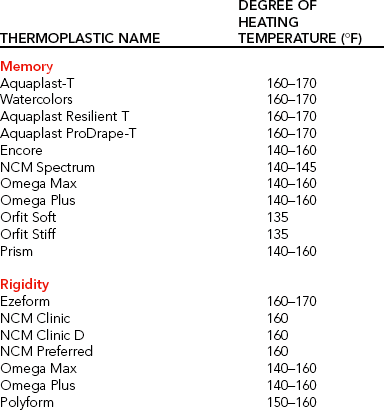

inch will soften and harden more quickly than thicker materials. Therefore, therapists who are novices in splinting may find it easier to splint with  -inch-thick materials than with thinner materials [McKee and Morgan 1998].Table 3-1 lists property guidelines for thermoplastic materials. (See also Laboratory Exercise 3-1.)

-inch-thick materials than with thinner materials [McKee and Morgan 1998].Table 3-1 lists property guidelines for thermoplastic materials. (See also Laboratory Exercise 3-1.)

Process: Making the Splint

Making a good pattern for a splint is necessary for success. Giving time and attention to the making of a well-fitting pattern will save the splintmaker’s time and materials involved in making adjustments or an entirely new splint. A pattern should be made for each person who needs a splint. Generic patterns rarely fit persons correctly without adjustments. Having several sizes of generic patterns cut out of aluminum foil for trial fittings may speed up the pattern process. A standard pattern can be reduced on a copy machine for pediatric sizes.

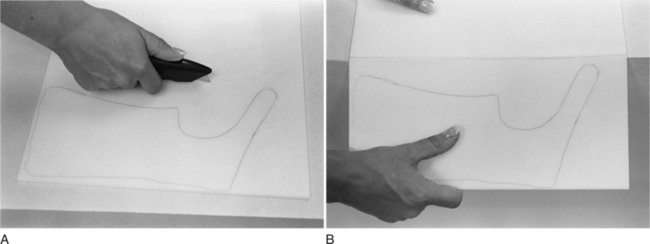

To make a custom pattern, the therapist traces the outline of the person’s hand (or corresponding body part) on a paper towel (or foil), making certain that the hand is flat and in a neutral position. If the person’s hand is unable to flatten on the paper, the contralateral hand may be used to draw the pattern and fit the pattern. If the contralateral hand cannot be used, the therapist may hold the paper in a manner so as to contour to the hand position. The therapist marks on the paper any hand landmarks needed for the pattern before the hand is removed. The therapist then draws the splint pattern over the outline of the hand, cuts out the pattern with scissors, and completes final sizing.

Fitting the Pattern to the Client

As shown inFigure 3-1, moistening the paper and applying it to the person’s hand helps the therapist determine which adjustments are required. Patterns made from aluminum foil work well to contour the pattern to the extremity. If the pattern is too large in areas, the therapist can make adjustments by marking the pattern with a pen and cutting or folding the paper. Sometimes it is necessary to make a new pattern or to retrace a pattern that is too small or that requires major adjustments. The therapist ensures that the pattern fits the person before tracing it onto and cutting it out of the thermoplastic material. It is well worth the time to make an accurate pattern because any ill-fitting pattern directly affects the finished product.

Figure 3-1 To make pattern adjustments, moisten the paper and apply it to the extremity during fitting.

Throughout this book, detailed instructions are provided for making different splint patterns. One should keep in mind that therapists with experience and competency may find it unnecessary to identify all landmarks as indicated by the detailed instructions. Form 3-1 lists suggestions helpful to a beginning splintmaker when drawing and fitting patterns.

Tracing, Heating, and Cutting

After making and fitting the pattern to the client, the therapist places it on the sheet of thermoplastic material in such a way as to conserve material and then traces the pattern on the thermoplastic material with a pencil. (Conserving materials will ultimately save expenses for the clinic or hospital.) Pencil lines do not show up on all plastics. Using an awl to “scratch” the pattern outline on the plastics works well. Another option is to use grease pencils or china pencils. Caution should be taken when a therapist uses an ink pen, as the ink may smear onto the plastic. However, the ink may be removed with chlorine.

Once the pattern is outlined on a sheet of material, a rectangle slightly larger than the pattern is cut with a utility knife (Figure 3-2). After the cut is made, the material is folded over the edge of a countertop. If unbroken, the material can be turned over to the other side and folded over the countertop’s edge. Any unbroken line can then be cut with a utility knife or scissors.

Figure 3-2 (A) A utility knife is used to cut the sheet of material with the pattern outline on it in such a way that the thermoplastic material fits in the hydrocollator or fry pan. (B) The score from the utility knife is pressed against a countertop.

Heating the Thermoplastic Material

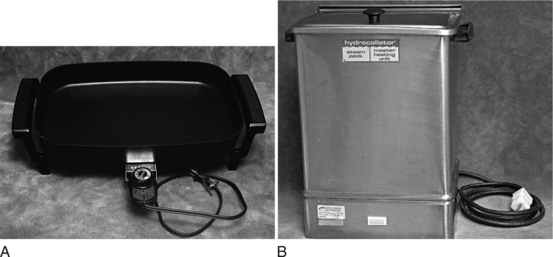

Thermoplastic material is softened in an electric fry pan, commercially available splint pan, or hydrocollator filled with water heated to approximately 135° to 180°F (Figure 3-3). (Some materials can be heated in a microwave oven or in a fry pan without water.) To ensure temperature consistency, the temperature dial should be marked to indicate the correct setting of 160°F by using a hook-and-loop (Velcro) dot or piece of tape. When softening materials vertically in a hydrocollator, the therapist must realize the potential for problems associated with material stretching due to gravity’s effects. If a fry pan is used, the water height in the pan should be a minimum of three-fourths full (approximately 2 inches deep).

Adequate water height allows a therapist to submerge portions of the splint later when making adjustments. If the thermoplastic material is larger than the fry pan, a portion of the material should be heated. When the material is soft, a paper towel is placed on the heated portion and the rest of the material is folded on the paper towel. A nonstick mesh may be placed in the bottom of a fry pan to prevent the plastic from sticking to any materials or particles. However, it can create a mesh imprint on the plastic. When the thermoplastic piece is large (and especially when it is a high-stretch material), it is a great advantage to lift the thermoplastic material out of the splint pan on the mesh. This keeps the plastic flat and minimizes stretch.

Cutting the Thermoplastic Material

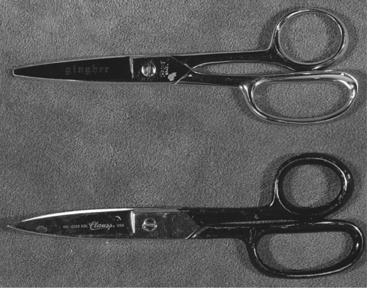

After removing the thermoplastic material from the water with a spatula or on the mesh, the therapist cuts the material with either round- or flat-edged scissors (Figure 3-4). The therapist uses sharp scissors and cuts with long blade strokes (as opposed to using only the tips of the scissors). Scissors should be sharpened at least once each year, and possibly more often, depending on use. Dedicating scissors for specific materials will prolong the edge of the blade. For example, one pair of scissors should be used to cut plastic, another for paper, another for adhesive-backed products, and so on. Sharp scissors in a variety of sizes are helpful for difficult contoured cutting and trimming. Splinting solvent or adhesive removers will remove adhesive that builds up on scissor blades.

Reheating the Thermoplastic Material

After the pattern is cut from the material, it is reheated. During reheating, the therapist positions the person to the desired joint position(s). If the therapist anticipates positioning challenges and needs to spend time solving problems, positioning should be done before the material is reheated to prevent the material from overheating [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, 1999]. During this time frame, the therapist explains that the material will be warm and that if it is too intolerable the client should notify the therapist. The therapist completes any pre-padding of boney prominences and covers dressings and padding (the LTT will stick to these if not covered with stockinette) prior to the molding process.

Positioning the Client for Splinting

There are several client positioning options. The client is placed in a position that is comfortable, especially for the shoulder and elbow. A therapist may use a gravity-assisted position for hand splinting by having the person rest the dorsal wrist area on a towel roll while the forearm is in supination to maintain proper wrist positioning. Alternatively, a therapist may ask the person to rest the elbow on a table and splint the hand while it is in a vertical position.

For persons with stiffness, a warm water soak or whirlpool, ultrasound, paraffin dip, or hot pack can be used before splinting. Splinting is easiest when persons take their pain medication 30 to 60 minutes before the session. For persons with hypertonicity, it may be effective to use a hot pack on the joint to be splinted. Then the joint should be positioned and splinted in a submaximal range. When splinting is done after warming or after a treatment session, the joints are usually more mobile. However, the splint may not be tolerated after the preconditioning effect wears off. Thus, the therapist must find a balance to complete a gentle warm-up and avoid aggressive preconditioning treatments [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, 1999]. Goniometers are used, when possible, to measure joint angles for optimal therapeutic positioning.

Molding the Splint to the Client

Once positioning is accomplished, the therapist retrieves the softened thermoplastic material. Any hot water is wiped off on a paper towel, a fabric towel, or a pillow that has a dark-colored pillowcase on it. (The dark-colored pillowcase helps identify any small scraps or snips of material from previous splinting activities that may adhere to the thermoplastic material.) The therapist checks the temperature of the softened plastic and finally applies the thermoplastic material to the person’s extremity. The thermoplastic material may be extremely warm, and thus the therapist should use caution to prevent skin burn or discomfort. For persons with fragile skin who are at risk of burns, the extremity may be covered with stockinette before the splinting material is applied. Some thermoplastic materials will stick to hair on the person’s skin, but this situation can be avoided by using stockinette or lotion on the skin before application of the splinting material.

Therapists may choose to hasten the cooling process to maintain joint position and splint shape. Several options are available. First, a therapist can use an environmentally friendly cold spray. Cold spray is an agent that serves as a surface coolant. Cold spray should not be used near persons who have severe allergies or who have respiratory problems. Because the spray is flammable, it should be properly stored. A second option is to dip the person’s extremity with the splint into a tub of cold water. This must be done cautiously with persons who have hypertonicity because the cold temperature could cause a rapid increase in the amount of tone, thus altering joint position. Similar to using a tub of cold water, the therapist may carefully walk the person wearing the splint to a sink and run cold water over the splint. Third, a therapist can use frozen Theraband and wrap it around the splint to hasten cooling. An Ace bandage immersed in ice water and then wrapped around the splint may also speed cooling [Wilton 1997]. However, Ace bandages often leave their imprints on the splinting material.

Making Adjustments

Adjustments can be made to a splint by using a variety of techniques and equipment. While the thermoplastic material is still warm, therapists can make adjustments to splints—such as marking a trim line with their fingernails or a pencil or stretching small areas of the splint. The amount of allowable stretch depends on the property of the material and the cooling time that has elapsed. If the plastic is too cool to cut with scissors, the therapist can quickly dip the area in hot water. A professional-grade metal turkey baster or ladle assists in directly applying hot water to modify a small or difficult-to-immerse area of the splint.

A heat gun (Figure 3-5) may also be used to make adjustments. A heat gun has a switch for off, cool, and hot. After using a heat gun, before turning it to the off position the therapist sets the switch to the cool setting. This allows the motor to cool down and protects the motor from overheating. When a heat gun is on the hot setting, caution must be used to avoid burning materials surrounding it and reaching over the flow of the hot air.

Heat guns must be used with care. Because heat guns warm unevenly, therapists should not use them for major heating and trimming. Use of heat guns to soften a large area on a splint may result in a buckle or a hot/cold line. A hot/cold line develops when a portion of plastic is heated and its adjacent line or area is cool. A buckle can form where the hot area stretched and the cooled material did not. Heat guns are helpful for warming small focused areas for finishing touches. When using a heat gun, it is best to continually move the heat gun’s air projection on the area of the splint to be softened. In addition, the area to be softened should be heated on both sides of the plastic. Attachments for the heat gun’s nozzle are available to focus the direction of hot air flow. Small heat guns are available and may assist in spot heating thinner plastics and areas of the splint that have attachments that cannot be exposed to heat (i.e., splint line) [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, 1999 and 2006].

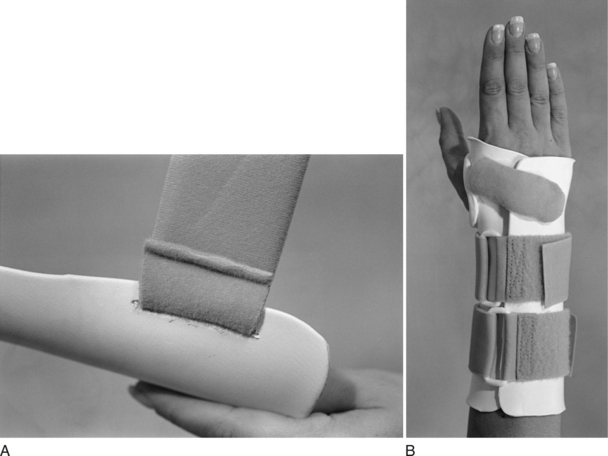

Strapping

After achieving a correct fit, the therapist uses strapping materials to secure the splint onto the person’s extremity. Many strapping materials are available commercially. Velcro hook and loop, with or without an adhesive backing, is commonly used for portions of the strapping mechanism. Velcro is available in a variety of colors and widths. Therapists trim Velcro to a desired width or shape. For cutting self-adhesive Velcro, sharp scissors other than those used to cut thermoplastic material should be used. The adhesive backing from strapping materials often accumulates on the scissor blades and makes the scissors a poor cutting tool. The adhesive can be removed with solvent. When a self-adhesive Velcro hook is used, the corners should be rounded. Rounded corners decrease the chance of corners peeling off the splint. Precut self-adhesive Velcro hook dots can be purchased and save therapists’ time not only in cutting and rounding corners but in keeping adhesive off scissors. A clinic may have an aid or volunteer cut self-adhesive Velcro hook pieces that have rounded corners to save therapists’ time. Briefly heating the adhesive backing and the site of attachment on the splint with a heat gun increases the bond of the hook or loop to the thermoplastic material.

Alternative pressure-sensitive straps, which attach to the Velcro hook, are available. Strapping materials are often padded to add comfort, but these tend to be less durable than Velcro loop. Some padded strapping materials, when cut, have a self-sealing or more finished look than others. Soft straps without self-sealing edges tend to tear apart with use over time. The therapist may cut extra straps and give them to the client to take home if necessary. Commercially sold splint strapping packs provide all the straps needed for a forearm-based splint in one convenient package.

Spiral or continuous strapping can be employed to evenly distribute pressure along the splint. A spiral or continuous strap is a piece of soft strapping that is spiraled around the forearm portion of a splint. Rather than several pieces of Velcro hook being cut to attach to selected sites on the splint, both sides of the forearm trough can be the sites for placement of a long strip of Velcro hook. The spiral or continuous strap attaches to the Velcro hook. Spiral or continuous straps can be used in conjunction with compression gloves for persons who have edematous hands. The spiral strapping and glove prevent the trapping of distal edema.

To prevent the person wearing the splint from losing straps, the therapist may attach one end of the strap to the splint with a rivet or strong adhesive glue. Another helpful technique is to heat the end of a metal butter knife with a heat gun and push it through the splinting material to make a slit. The area is cooled and the knife is removed. The therapist threads the strap through the slit, folds the strap end over itself, and sews the strap together (Figure 3-6A). D-ring straps are available commercially. This type of strapping material affords the greatest control over strap tension and splint migration (Figure 3-6B).

Figure 3-6 (A) Strap is threaded through a slit in forearm trough. The strap is overlapped upon itself and securely sewn. (B) D-ring strapping mechanism.

Strap placement is critical to a proper fit. Many therapists fail to place the straps strategically for joint control and render the splint useless. [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, 1999] particularly stresses wrist strap placement at the wrist, rather than proximal to the wrist.

Padding and Avoiding Pressure Areas

Therapists attempt to remediate portions of splints that may potentially cause pressure areas or irritations. The therapist can use a heat gun to push out areas of the thermoplastic material that may irritate bony prominences. Any bony prominences should be padded before splint formation. Padding should not be added as an afterthought. Padding over these areas or lining of an entire splint may also be considered to prevent irritation. Sufficient space must be made available for the thickness of the padding. Otherwise, the pressure may actually increase over the area.

Use of a self-adhesive gel disk (other paddings will work as well) is helpful in cushioning bony prominences, such as the ulnar head. To use gel disks, the therapist adheres the disk to the person’s skin and then forms the splint over the gel disk. Upon cooling of the splint, the gel disk is removed from the person and adhered to the corresponding area inside the splint. To bubble out or dome areas over bony prominences, a therapist can place elastomer putty over the prominence before applying the warm thermoplastic material.

If an entire splint is to be lined with padding, the therapist can use the splint pattern to cut out the padding needed. The therapist can trace the pattern ¼ to ½ inch larger on the padding if the intention is to overlap the self-adhesive padding onto the splint’s edges, as shown inFigure 3-7.

Gel lining is often used within the interior of the splint to assist in managing scars. Two types of gel lining are available: silicone gel and polymer gel. Silicone gel sheets, which are flexible and washable, can be cut with scissors into any shape. The silicone gel sheets are often positioned in conjunction with pressure garments or splints or positioned with Coban. Persons using silicone gel sheets must be monitored for the development of rashes, skin irritations, and maceration. Polymer gel sheets are filled with mineral oil, which is released into the skin to soften “normal,” hypertrophic, or keloid scars. Polymer gel sheets adhere to the skin and can be used with pressure garments or splints.

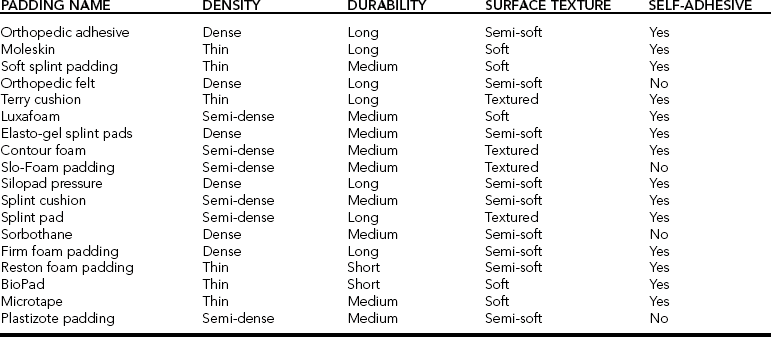

Various padding systems are commercially available in a variety of densities, durabilities, cell structures, and surface textures [North Coast Medical 1999]. A self-adhesive backing is available with some types of padding, which saves the therapist time and materials because glue does not have to be used to adhere the padding to a splint. Some cushioning and padding materials have an adhesive backing for easy application. Other types of padding are applied to any flat sheet of thermoplastic material and put in a heavyweight sealable plastic bag before immersion in hot water. The padding and thermoplastic material are adhered prior to molding the splint on the client. Putting the plastic with the padding adhered to it in a plastic bag prevents the padding from getting wet and can save the therapist time.Table 3-2 outlines available padding products.

Table 3-2

Padding Categorization Guidelines

From North Coast Medical Hand Therapy Catalog (1999), San Jose, California.

Padding has either closed or open cells. Closed-cell padding resists absorption of odors and perspiration, and can easily be wiped clean. Open-cell padding allows for absorption. Because of low durability and soiling, padding used in a splint may require periodic replacement. Some types of padding are virtually impossible to remove from a splint. Thus, when padding needs replacement so does the splint.

Edge Finishing

Edges of a splint should be smooth and rolled or flared to prevent pressure areas on the person’s extremity. The therapist may use a heat gun or heated water in a fry pan or hydrocollator to heat, soften, and smooth edges. Fingertips moistened with water or lotion help avoid finger imprints on the plastic. Most of the newer thermoplastic materials have self-finishing edges. When the warm plastic is cut, it does not require detailed finishing other than that necessary to flare the edges slightly.

Reinforcement

Strength of a splint increases when the plastic is curved. Thus, a plastic that has curves will be stronger than a flat piece of thermoplastic material. When the thermoplastic material has been stretched too thin or is too flexible to provide adequate support to an area such as the wrist, it must be reinforced. If an area of a splint requires reinforcement, an additional piece of material bonded to the outside of the splint will increase the strength. A ridge molded in the reinforcement piece provides additional strength (Figure 3-8).

Prefabricated Splints

In addition to making a custom-made splint, therapists have options to use prefabricated splints. The manufacturing of commercially available prefabricated splints is market driven. Therefore, changes in style or materials may appear from year to year. Styles and materials are also affected by the manufacturing processes. Manufacturers are slow to change materials and design even when the market requests it. When a prefabricated splint’s material, cut, or style does not sell well, it may be discontinued or replaced with a different design. Vendors often attempt to manufacture prefabricated splints for broad populations.

Manufacturing for a specific population is often costly and not financially rewarding unless that “specific population” has a large market. Improvements in the quality of prefabricated splints are affected by market economics, which stimulate companies to manufacture better products in terms of comfort, durability, and therapeutics. Current catalogs serve as the ultimate reference to what is available. Vendors selling prefabricated splints are listed at the end of this chapter.

In addition to market economics, the proliferation of various styles of prefabricated splints can be attributed to two factors. First, the proliferation of prefabricated splints is influenced by third-party payers’ willingness to reimburse for splints. For example, the variety of soft hand and wrist splints for the elderly is an outgrowth of Medicare reimbursement policies during the 1980s and early 1990s. In contrast, because pediatric splints are typically not well reimbursed (except for orthopedic injuries) the market is small. Pediatric splints marketed for orthopedic needs tend to be smaller versions of adult-size splints.

Another reason for the proliferation of prefabricated splints involves the conceptual advances in design and the recognition that a need for these types of splints exists. For example, the refinement of wrist and thumb prefabricated splints has been influenced by the advancement of ergonomic knowledge and the public’s awareness of the incidence and effects of cumulative trauma disorders.

Prefabricated splints are available from numerous vendors in a variety of styles, materials, and sizes. Prefabricated splints are available for the head, neck, joints of the upper and lower extremities, and trunk. Typically, prefabricated splints are ordered by size—and in some cases for right or left extremities. Some splints have a universal size, meaning that one splint fits the right or left hand. Before deciding to provide a prefabricated splint for a client, the therapist must be aware of the advantages and disadvantages of prefabricated splints.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Prefabricated Splints

The advantages and disadvantages of using prefabricated splints are listed inBox 3-1.

Advantages

An obvious advantage of using a prefabricated splint is saving of the therapist’s time and effort. The time required to design a pattern, trace and cut the pattern from plastic, and mold the splint to the person is saved when a prefabricated splint is used. However, one should keep in mind the time and expense involved in ordering and paying for the prefabricated splints. The costs and wage-hours involved in processing an order through a large facility are considerable. Maintaining inventory takes time and space.

If a prefabricated splint is in a clinic’s inventory, the ability to immediately assess the splint in terms of therapeutics and customer satisfaction is an advantage. After splint application, the client is readily able to see and feel the splint. When fabricating a custom splint, the therapist may find that it does not meet the client’s expectations or needs. When this occurs, a considerable amount of time and effort is expended in modifying the current splint or in designing and fabricating an entirely new splint. With prefabricated splints, an educated trial-and-error process can be used to find the best splint to meet the client’s goals and therapeutic needs.

A third advantage is the variety of materials used to make prefabricated splints. Many prefabricated splint materials offer sophisticated technology that cannot be duplicated in the clinic. For example, a prefabricated splint made from high-temperature thermoplastic material is often more durable than a counterpart made of low-temperature thermoplastic material. Softer materials (combinations of fabric and foam) may be more acceptable to persons, especially those with rheumatoid arthritis.

Soft splints can be more comfortable than the LTT ones usually used for custom splinting. In a study comparing soft versus hard resting hand splints in 39 persons with rheumatoid arthritis, Callinan and Mathiowetz [1996] found that compliance with the splint wearing was significantly better with the soft splint (82%) than with the hard splint (67%). However, therapists must realize that a person who needs rigid immobilization for comfort will not prefer a soft splint because soft splints allow some mobility to occur. Some clients may think that the sports-brace appearance of a prefabricated splint is more aesthetically pleasing than the medical appearance of a custom-fabricated splint. For these clients, wearing compliance may increase.

Disadvantages

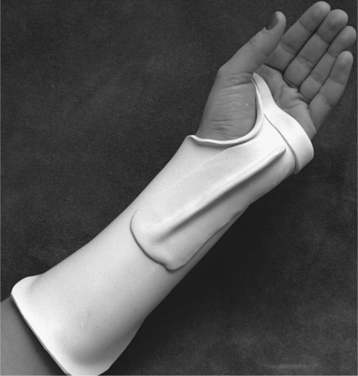

Several disadvantages must be noted with regard to prefabricated splints. A major disadvantage of using a prefabricated splint is that a custom, unique fit is often compromised. Soft prefabricated splints vary in how much they can be adjusted. If a high degree of conformity or a specialized design is needed, a prefabricated splint will usually not meet the person’s needs. LTT prefabricated splints can be spot heated and adjusted somewhat (Figure 3-9), but they will never conform like a custom-made splint of the same material. Some prefabricated splints require adjustments. For example, thumb splints may require adjustment of the palmar bar to prevent chafing in the thumb web space. Other preformed splints must be adjusted by trimming the forearm troughs for proper strap application.

Figure 3-9 Adjustments can be made to commercial LTT splints with the use of a heat gun. [Courtesy Medical Media Service, Veterans Administration Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina.]

The second disadvantage of prefabricated splints is related to the therapist’s lack of control over customization. When using prefabricated splints, therapists often have little or no control over joint angle positioning. Often a therapeutic protocol or specific client need prescribes a specific joint angle for positioning. In such instances, the therapist must select a prefabricated splint that is designed with the appropriate joint angle(s) or choose one that can be adjusted to the correct angle. If unavailable, a custom splint is warranted. For example, therapists must use prefabricated splints cautiously with persons who have fluctuating edema. The splint and its strapping system must be able to accommodate the extremity’s changing size. In addition, when conditions require therapists to create unique splint designs the desired prefabricated splints may not always be commercially available.

A third disadvantage of using a prefabricated splint is that the splint may not be stocked in the clinic and may have to be ordered. Many clinics cannot afford to stock a wide variety of prefabricated splints because of cost and storage restrictions. When a splint must be applied immediately and the prefabricated splint is not in the clinic’s stock, a time delay for ordering it is unacceptable. A custom-made splint should be fabricated instead of waiting for the prefabricated splint to arrive.

Once the advantages and disadvantages have been weighed, a decision must be made regarding whether to use a prefabricated or a custom-made splint. The therapist engages in a clinical reasoning process to select the most appropriate splint.

Selecting a Splint

Therapists rarely use custom or prefabricated splints for 100% of their clientele. The therapist uses clinical reasoning based on a frame of reference to select the most appropriate splint. There is little outcome research addressing custom and prefabricated splint usage. To determine whether to use a prefabricated or a custom-made splint, the therapist must know the specific splinting needs of the person and determine how best to accomplish them. Would a soft material or an LTT best meet the person’s needs? How would the function and fit of a prefabricated splint compare with that of a custom-made splint? To properly evaluate whether a prefabricated splint or a custom-made splint would best meet a person’s needs, the factors and questions discussed in the following sections must be considered and answered.

Diagnosis

Is a prefabricated splint available for the diagnosis? Which splint design meets the therapeutic goals? Is there a match between the therapeutic goals and the design of a prefabricated or soft splint? For example, if a therapist must provide a splint to immobilize a wrist joint in neutral a commercial splint must have the ability to position and immobilize the wrist in a neutral position.

Age of the Person

Is the client at an age where he or she may have an opinion about the splint’s cosmesis? What special considerations are there for a geriatric or pediatric person? (See Chapters 15 and 16.) For example, an adolescent may be unwilling to wear a custom-made elastic tension radial nerve splint at school because of its appearance. However, the adolescent might agree to wear a prefabricated wrist splint because of its less conspicuous sports-brace appearance.

Medical Complications

Does the person have compromised skin integrity, vascular supply, or sensation? Is the person experiencing pain, edema, or contractures? Medical conditions must be considered because they may influence splint design. For example, the therapist may choose a splint with wide elastic straps to accommodate the change in the extremity’s circumference for a person who has fluctuating edema.

Goals

What are the client’s goals? What are the therapeutic goals? The therapist determines the client’s priorities and goals from an interview. The therapist can facilitate clients’ compliance by understanding each person’s capabilities and expectations.

Splint Design

Which joints must be immobilized or mobilized? Will the splint achieve the desired therapeutic goals? Avoid over-splinting. Do not immobilize unnecessary joints. Any splint that limits active range of motion may result in joint stiffness and muscle weakness. For example, if only the hand is involved use a prefabricated hand-based splint to avoid limiting wrist motion.

Occupational Performance

Does the splint affect the client’s occupational performance? Does the splint maintain, improve, or eliminate occupational performance? Does wearing the splint interfere with participation in valued activities? Occupational performance should be considered, regardless of the age of the client. Stern et al. [1996] studied 42 persons with rheumatoid arthritis and reported that the “major use of wrist orthoses occurs during instrumental activities of daily living where greater stresses are placed on the wrist” (p. 30). Therapists should observe or ask the client about his or her occupational participation while wearing the splint. Functional problems that occur while the splint is being worn require problem solving. Resolution of functional problems may lead to a modification of performance technique, an adjustment in the wearing schedule, or a change in the splint’s design.

Person’s or Caregiver’s Ability to Comply with Splinting Instructions

Is the person or caregiver capable of following written and verbal instruction? Is the person motivated to comply with the wearing schedule? Are there any factors that may influence compliance? Forgetfulness, fear, cultural beliefs, values, therapeutic priorities, and confusion about the splint’s purpose and schedule may influence compliance. A therapist should consider a person’s motivation, cognitive functioning, and physical ability when determining a splint design and schedule.

Compliance tends to increase with proper education [Agnew and Maas 1995]. For example, persons receiving education often have a better outcome if instructions are presented in verbal and written formats [Schneiders et al. 1998]. Therapists often explain to clients that long-term gains are usually worth short-term inconvenience. When compliance is a problem, the splint program may have to be modified.

Independence with Splint Regimen

If there is no caregiver, can the person independently apply and remove the splint? Can the person monitor for precautions, such as the development of numbness, reddened areas, pressure sores, rash, and so on? For example, Fred (an 80-year-old man) is in need of bilateral resting hand splints to reduce pain from a rheumatoid arthritis exacerbation. His 79-year-old wife is forgetful. Fred’s therapist designs a wearing schedule so that Fred can elicit assistance from his wife. The therapist recommends putting the splints on the bed so that Fred can remind his wife to assist him in donning the splints before bedtime.

Comfort

Does the person report that the splint is comfortable? Does the person have any condition, such as rhumatoid arthritis, that may warrant special attention to comfort? Are there insensate areas that may be potentially harmed by the splint? A therapist should monitor the comfort of a commercial splint on each client. If the splint is not comfortable, a person is not likely to wear it. In studying three prefabricated wrist supports for persons with rheumatoid arthritis, Stern et al. [1997] concluded that “satisfaction ¼ appears to be based not only on therapeutic effect, but also the comfort and ease of its use” (p. 27).

Environment

In what type of environment will the person be wearing the splint? How might the environment affect splint wear and care?

Industrial Settings.: Industrial settings may warrant splints made of more durable materials such as leather, Kydex, or metal. For example, splints may need extra cushioning to buffer vibration from machinery or tools that often aggravate cumulative trauma disorders.

Long-Term Care Settings.: Therapists providing commercial splints to residents in long-term care settings must consider the influence of multiple caretakers and the fragile skin of many elders. The following suggestions may assist in dealing with multiple caretakers and elders’ fragile skin. Splints should be labeled with the person’s name. To avoid strap loss, consider attaching them to the splint or choose a splint with attached straps. Select splints made from materials that are durable and easy to keep clean. Colored commercial splints provide a contrast and may be more easily identified and distinguished from white or neutral-colored backgrounds.

School Settings.: Several factors relating to pediatric splints must be considered by the therapist. Pediatric prefabricated splints should be made of materials that are easy to clean. Splints for children should be durable. Consider attaching straps to the splint or choose a splint with attached straps. Because multiple caretakers (parents and school personnel) are typically involved in the application and wear schedule, instructions for wear and care should be clear and easy to follow. When the child is old enough, personal preferences as well as parental preferences should be considered during splint selection. If the splint is for long-term use, the therapist must remember that the child will grow. If possible, the therapist should select a splint that can be adjusted to avoid the expense of purchasing a new splint. In addition, splints with components that may scratch or be swallowed by the child should be avoided.

Education Format

What education do the client and caregiver need to adhere to the splint-wearing schedule? What is the learning style of the person and caregiver? How can the therapist adjust educational format to match the person’s and caregiver’s learning styles? Educating clients and caregivers in methods consistent with their preferred learning style may increase compliance. Learning styles include kinesthetic, visual, and auditory [Fleming and Mills 1993].

Written instructions should include the splint’s purpose, wearing schedule, care, and precautions. Because correct use of a splint affects treatment outcome, the client should demonstrate an understanding of instructions in the presence of the therapist. A therapist may complete a follow-up phone call at a suitable interval to detect any problems encountered by the client or caregiver in regard to the prefabricated splint [Racelis et al. 1998]. (See also Chapter 6.)

Fitting and Making Adjustments

If a decision is made to use a prefabricated splint and a selection is made, the therapist must evaluate it for size, fit, and function. Just as with custom splints, a particular prefabricated splint design does not work for every client. As professionals who provide splints to clients, therapists have an obligation and duty to fit the splint to the client rather than fitting the client to the splint! The implications of this duty suggest that clinics should stock a variety of commercial splint designs. Although a large clinic’s overhead is expensive, limiting choices may result in poor client compliance [Stern et al. 1997]. When a variety of splint designs are available, a trial-and-error approach can be used with commercial splints because most clients are able to report their preference for a splint after a few minutes of wear. When fitting a client with a commercial splint, the therapist should ask the following questions [Stern et al. 1997]:

• Does the splint feel secure on your extremity?

• Does the splint or its straps rub or irritate you anywhere?

• When wearing the splint, does your skin feel too hot?

• What activities will you be doing while wearing your splint?

• When you move your extremity while wearing the splint, do you experience any pain?

• Does the splint feel comfortable after wearing it for 20 to 30 minutes?

In addition to fit and size, therapists must evaluate the prefabricated splint’s effect on function. Stern et al. [1996] investigated three commercial wrist splints for their effect on finger dexterity and hand function. Dexterity was reduced similarly across the three splints. In addition, dexterity was significantly affected when the splints were used during tasks that required maximum dexterity. In such cases, therapists and clients should decide whether dexterity reduction outweighs the known benefits of splinting.

Jansen et al.’s [1997] research indicated that grip strength decreased when clients wore wrist splints. However, for women with rheumatoid arthritis grip strength increased during splint wear [Nordenskiöld 1990]. A reduction in grip strength occurs because wrist splints prevent the amount of wrist extension required to generate maximal grip strength in the “normal” population. Those with rheumatoid arthritis have poor wrist stability. Thus, the splints allow them to generate improved grip strength because of improved stability. Prefabricated splints often require adjustments to appropriately fit the person and condition.

Technical Tips for Custom Adjustments to Prefabricated Splints

The following points describe common adjustments made to commercial splints.

• Therapists should ensure that splints do not irritate soft tissue, reduce circulation, or cause paresthesias [Stern et al. 1997]. Adjustments may include flaring ends, bubbling out pressure areas, or addition of padding.

• Although soft splints are intended to be used as is, minor modifications to customize the fit to a person can be accomplished. Some soft splints can be trimmed with scissors to customize fit. If a soft splint has stitching to hold layers together, it will need to be resewn. (Note that it is beneficial to have a sewing machine in the clinic.)

• Modification methods for preformed splints include heating, cutting, or reshaping portions of the LTT splint. Minor modifications can be made with the use of a heat gun, fry pan, or hydrocollator to soften LTT preformed splints for trimming or slight stretching.

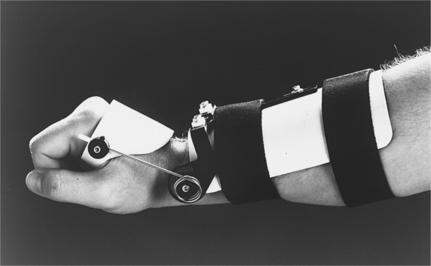

• Some elastic traction/tension prefabricated splints may be adjusted by bending and repositioning portions of wire, metal, or foam splint components. Occasionally, technical literature accompanying the splint describes how to make adjustments in the amount of traction. Often traction can be adjusted with the use of an Allen wrench on the rotating wheels on a hinge joint, as shown inFigure 3-10. When there are no instructions describing how to make adjustments on prefabricated splints, the therapist must use creative problem-solving skills to accomplish the desired changes.

Figure 3-10 Tension is adjusted with an Allen wrench on the rotating wheels on the hinge joint of this splint.

• When a static prefabricated splint is used and serial adjustments are required to accommodate increases in passive range of motion (PROM), the splint must be reheated and remolded to the client. It is advantageous to select a prefabricated splint made of material that has memory properties to allow for the serial adjustments.

• The amount of force provided by some static-progressive splints is made through mechanical adjustment of the force-generating device. Force may be adjusted by manipulating the splint’s turnbuckle, bolt, or hinge.

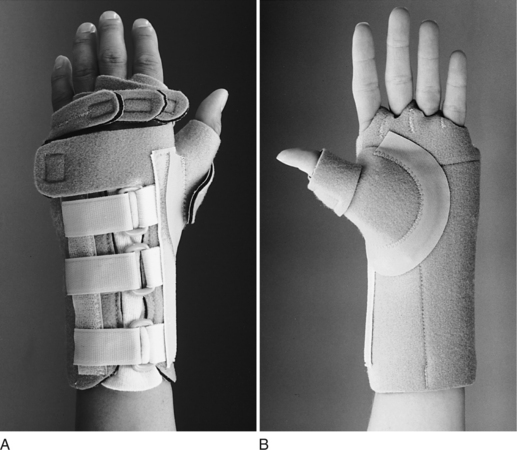

• The force exerted by elastic traction components of a prefabricated splint is also made through adjustments of the force-generating device. Therapists can adjust the forces by changing elastic component length by gradually moving the placement of the neoprene or rubber band–like straps on a splint throughout the day, as shown inFigure 3-11.

Figure 3-11 (A) The Rolyan In-Line splint with thumb support can be adjusted by loosening or tightening the neoprene straps. (B) Volar view of the Rolyan In-Line splint with thumb support. [Courtesy Rehabilitation Division of Smith & Nephew, Germantown, Wisconsin.]

• Adding components to prefabricated splints can be helpful. For example, putty-elastomer inserts that serve as finger separators can be used in a resting hand splint. Finger separators add contour in the hand area to maintain the arches. A therapist may choose to add other components, such as wicking lining or padding.

• Prefabricated splints can be modified by replacing parts of them with more adjustable materials. For example, if a wrist splint has a metal stay replacing it with an LTT stay results in a custom fit with the correct therapeutic position.

• It is often necessary to customize strapping mechanisms for prefabricated splints. The number and placement of straps are adjusted to best secure the splint on the person. Straps must be secured properly, but not so tightly as to restrict circulation. Straps coursing through web spaces must not irritate soft tissue. The research by Stern et al. [1997] on commercial wrist splints indicates that clients with stiff joints experienced difficulty threading straps through D-rings. Clients reported having to use their teeth to manipulate straps. Straps that are too long also appear to be troublesome because they catch on clothing [Stern et al. 1997].

• Stern et al. [1994] showed that although commercial splints are often critiqued for being too short, some persons prefer shorter forearm troughs. Shorter splints seem to be preferred by clients when wrist support, not immobilization, is needed.

After the necessary adjustments are completed and a proper fit is accomplished, a therapist determines wearing schedule.

Wearing Schedule

Although there are no easy answers about wearing protocols, experienced therapists have several guidelines for decision making as they tailor wearing schedules to each client [Schultz-Johnson 1992].

• For splints designed to increase PROM, light tension exerted by a splint over a long period of time is preferable to high tension for short periods of time.

• For joints with hard end feels and PROM limitations, more hours of splint wear are warranted than for joints with soft end feels.

• Persons tolerate static splints (including serial and static-progressive splints) better than dynamic splints during sleep.

• When treatment goals are being considered, wearing schedules should allow for facilitation of active motion and functional use of joints when appropriate.

As with any splint provision, the splint-wearing schedule should be given in verbal and written formats to the person and caregiver(s). The wearing schedule depends on the person’s condition and dysfunction and the severity (chronic or acute) of the problem. The wearing schedule also depends on the therapeutic goal of the splint, the demands of the environment, and the ability of the person and caregiver(s).

Care of Prefabricated Splints

Always check the manufacturer’s instructions for cleaning the splint. Give the client the manufacturer’s instructions on splint care. If a client is visually impaired, make an enlarged copy of the instructions. For soft splints, the manufacturer usually recommends hand washing and air drying because the agitation and heat of some washers and dryers can ruin soft splints. Because air drying of soft splints takes time, occasionally two of the same splint are provided so that the person can alternate wear during cleaning and drying. The inside of LTT splints should be wiped out with rubbing alcohol. The outside of LTT splints can be cleaned with toothpaste or nonabrasive cleaning agents and rinsed with tepid water. Clients and caregivers should be reminded that LTT splints soften in extreme heat, as in a car interior or on a windowsill or radiator.

Precautions

In addition to selecting, fitting, and scheduling the wear of a prefabricated splint, the therapist must educate the client or caregiver about any precautions and how to monitor for them. There are several precautions to be aware of with the use of commercial splints. These are discussed in the section following.

Dermatological Issues Related to Splinting

Latex Sensitivity.: Some prefabricated splints contain latex. More latex-sensitive people, including clients and medical professionals, are being identified [Jack 1994, Personius 1995]. Therapists should request a list of both latex and latex-free products from the suppliers of commercial splints used.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis.: Recently, dermatologic issues related to neoprene splinting have come to therapists’ attention. Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) and miliaria rubra (prickly heat) are associated in some persons with the wearing of neoprene (also known as polychloroprene) splints [Stern et al. 1998]. ACD symptoms include itching, skin eruptions, swelling, and skin hemorrhages. Miliaria rubra presents with small, red, elevated, inflamed papules and a tingling and burning sensation. Before using commercial or custom neoprene splints, therapists should question clients about dermatologic reactions and allergies. If a person reacts to a neoprene splint, wear should be discontinued and the therapist should notify the manufacturer. An interface such as polypropylene stockinette may also serve to resolve the problem.

Clients need to be instructed not only in proper splint care but in hygiene of the body part being splinted. Intermittent removal of the splint to wash the body part, the application of cornstarch, or the provision of wicking liners may help minimize dermatologic problems. Time of year and ambient temperatures need to be considered by the therapist. For example, neoprene may provide desired warmth to stiff joints and increase comfort while improving active and passive range of motion. However, during extreme summer temperatures the neoprene splint may cause more perspiration and increase the risk of skin maceration if inappropriately monitored.

Ordering Commercial Splints

A variety of vendors sell prefabricated splints. Companies may sell similar splint designs, but the splint names can be quite different. To keep abreast of the newest commercial splints, therapists should browse through vendor catalogs, communicate with vendor sales representatives, and seek out vendor exhibits during meetings and conferences for the ideal “hands-on” experience.

It is most beneficial to the therapist and the client when a clinic has a variety of commercial splint designs and sizes for right and left extremities. Keeping a large stock in a clinic can be expensive. To cover the overhead expense of stocking and storing prefabricated splints, a percentage markup of the prefabricated splint is often charged in addition to the therapist’s time and materials used for adjustments.

Splint Workroom or Cart

Having a well-organized and stocked splinting area will benefit the therapist who must make decisions about the splint design and construct the splint in a timely manner. Clients who need splint intervention will also benefit from a well-stocked splint and splinting supply inventory. Readily available splinting materials and tools will expedite the splinting process.

Clinics should consider the services commonly rendered and stock their materials accordingly. In addition to a stocked splinting room, therapists may find it useful to have a splint cart organized for splinting in a client’s room or in another portion of the health care setting. The cart can assist the therapist in readily transporting splinting supplies to the client, rather than a client coming to the therapist. For therapists who travel from clinic to clinic, splinting supply suitcases on rollers are ideal. Splinting carts or cases should contain such items as the following:

Documentation and Reassessment

Splint provision must be well documented. Documentation assists in third-party reimbursement, communication to other health care providers, and demonstration of efficacy of the intervention. Splint documentation should include several elements, such as the type, purpose, and anatomic location of the splint. Therapists should document that they have communicated in oral and written formats with the person receiving the splint. Topics addressed with each person include the wearing schedule, splint care, precautions, and any home program activities.

In follow-up visits, documentation should include any changes in the splint’s design and wearing schedule. In addition, the therapist should note whether problems with compliance are apparent. The therapist should determine whether the range of motion is increasing with splint wearing time and draw conclusions about splint efficacy or compliance with the program. Function in and out of the splint should be documented. For example, the therapist determines whether the person can independently perform some type of function as a result of wearing the splint. The therapist must listen to the client’s reports of functional problems and solve problems to remediate or compensate for the functional deficit. If function or range of motion is not increased, the therapist will need to consider splint revision or redesign or counsel the client on the importance of splint wear.

The therapist should perform splint reassessments regularly until the person is weaned from the splint or discharged from services. Facilities use different methods of documentation, and the therapist should be familiar with the routine method of the facility. (Refer to the documentation portion of Chapter 6 for more information.)

Physical Agent Modalities

PAMs are defined as those modalities that produce a biophysiologic response through the use of light, water, temperature, sound, electricity, or mechanical devices [AOTA 2003, p. 1]. The AOTA’s PAM position paper indicates that “physical agent modalities may be used by occupational therapy practitioners as an adjunct to or in preparation for intervention that ultimately enhances engagement in occupation; physical agents may only be applied by occupational therapists who have documented evidence of possessing the theoretical background for safe and competent integration into the therapy treatment plan” [AOTA 2003, p. 1]. Therapists must comply with their respective state’s scope of practice requirements regarding the use of PAMs as preparation for splinting.

Experienced therapists often use PAMs as an adjunctive method to effect a change in musculoskeletal tissue. Select PAMs may be used before, during, or after splint provision for management of pain, to increase soft-tissue extensibility, reduce edema, increase tendon excursion, promote wound healing, and decrease scar tissue. Occasionally, PAMs are used to prepare the upper extremity for optimal positioning for splinting. Prior to using any PAM, the therapist must develop and use clinical reasoning skills to effectively select and evaluate the appropriate modality; identify safety precautions, indications, and contraindications; and facilitate individualized treatment outcomes.

The type of PAM selected and the parameter setting(s) affects the neuromuscular system and tissue response. Changes in tissue response depend on how sensory information is processed to produce a motor response. Thermotherapy (heat) and cryotherapy (cold) have a significant effect on the peripheral nervous system and on neuromuscular control, and may enhance sensory and motor function when applied as an adjunctive method.

Therapists who use PAMs to effect a change in soft tissue, joint structure, tendons and ligaments, sensation, and pain level must consider the agent’s effects on superficial structures within the skin (i.e., epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis). Because splints are usually applied to an extremity (e.g., hand or foot), therapists must consider which sensory structures are stimulated and which motor responses are expected when applying a PAM prior to splinting. PAMs can be generally categorized in numerous ways. An overview of superficial agents commonly used to position the client for splinting follows.

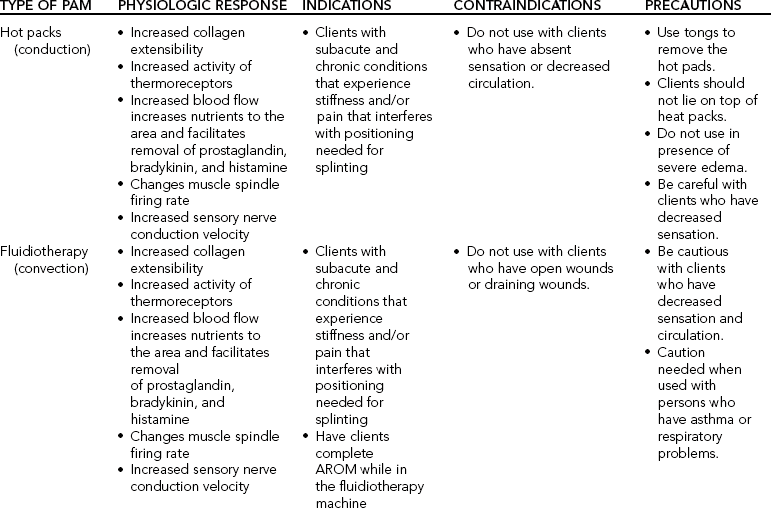

Superficial Agents

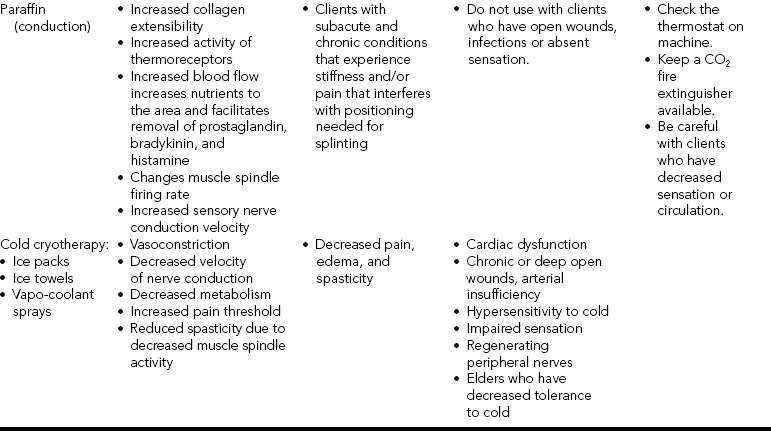

Superficial agents penetrate the skin to a depth of 1 to 2 cm [Cameron 2003]. These heating agents or thermotherapy agents include moist hot packs, fluidotherapy, paraffin wax therapy, and cryotherapy.Table 3-3 lists superficial agents and their physiologic responses, indications, contraindications, and precautions.

Heat Agents

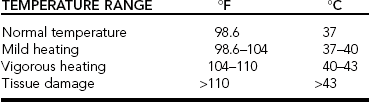

Heat is transferred to the skin and subcutaneous tissue by conduction or by convection. Conduction transfers heat from one object to another. Heat is conducted from the higher-temperature object to the lower-temperature material (such as moist heat packs or paraffin).Table 3-4 lists the temperature ranges for heat application.

Table 3-4

Temperature Ranges for Heat Application

Slack

Data from Bracciano A. Physical Agent Modalities: Theory and Application for the Occupational Therapist. Thorofare, NJ: Slack 2002.

Hot Packs

Superficial heat may be used for the relief of pain with noninflammatory conditions, general relaxation, and to stretch contractures and improve range of motion prior to splinting. For example, a client fractures her wrist and upon removal of the cast demonstrates limited wrist extension. The therapist intends to gain wrist extension by applying a moist hot pack to her wrist to increase the extensibility of the soft tissue. After application of the heat, the therapist is able to range the wrist into 10 degrees of wrist extension (an improvement from neutral). The client is splinted in slight wrist extension. A serial static splinting approach is used to gain a functional level of wrist extension.

Heat may be used to decrease muscle spasms by increasing nerve conduction velocity. According to Cameron [2003, p.159]: “Nerve conduction velocity has been reported to increase by approximately 2 meters/second for every 1°C (1.8°F) increase in temperature. Elevation of muscle tissue to 42°C (108°F) has been shown to decrease firing rate of the alpha motor neurons resulting in decreased muscle spasm.” Thus, in some cases heat is applied to reduce muscle spasms with a client who needs a splint.

Fluidotherapy

Convection transfers heat between a surface and a moving medium or agent. Examples of convection include fluidotherapy and whirlpool (hydrotherapy). Fludiotherapy is a form of dry heat consisting of ground cellulose particles made from corn husks. Circulated air heated to 100° to 118°F suspends the particles, creating agitation that functions much like a whirlpool turbine. Fluidotherapy is frequently used for pain control and desensitization and sensory stimulation. It is also used to increase soft tissue extensibility and joint range of motion and to reduce adhesions. Fluidotherapy is often used prior to applying static and dynamic hand splints for increasing soft-tissue extensibility. Fluidotherapy can increase edema due to the heat and dependent positioning of the upper extremity. Caution must be taken when using fluidotherapy on those who have asthma or when using fluidotherapy around those near the machine who have respiratory conditions, as particles can trigger a respiratory attack.

Paraffin Wax Therapy

Heated paraffin wax is another source of superficial warmth that transfers heat by conduction. The melting point of paraffin wax is 54.5°C (131°F). Administration includes dipping the clean hand in the wax for 10 consecutive immersions. The hand is then wrapped in a plastic bag and covered with a towel. Clients with open wounds, infections, or absent sensation should not receive paraffin therapy. Clients with chronic conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis may benefit from paraffin therapy to reduce stiffness prior to splinting.

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy is defined as the therapeutic use of cold modalities. Cold is considered a superficial modality that penetrates to a depth of 1 to 2 cm and produces a decrease in tissue temperature. Cold is transferred to the skin and subcutaneous tissue by conduction. Examples of cold modalities include cold packs, ice packs, ice towels, ice massage, and vapor sprays. Cold packs are usually stored at −5°C (23°F) and treatment time is 10 to 15 minutes. The effectiveness of the cold modality used depends on intensity, duration, and frequency of application.