Occupation-Based Splinting

“Man, through the use of his hands as they are energized by mind and will, can influence the state of his own health” [Reilly 1962, p. 2].

1 Define occupation-based treatment as it relates to splint design and fabrication.

2 Describe the influence of a client’s occupational needs on splint design and selection.

3 Review evidence to support preservation of occupational engagement through splinting.

4 Describe how to utilize an occupation-based approach to splinting.

5 Review specific hand pathologies that create the potential for occupational dysfunction.

6 Describe splint design options to promote occupational engagement.

7 Apply knowledge of application of occupation-based practice to a case study.

As stated eloquently by Mary Reilly [1962], this phrase reminds us that the hand, as directed by the mind and spirit, is integral to function. Occupation-based splinting is an approach that promotes the ability of the individual with hand dysfunction to engage in desired life tasks and occupations [Amini 2005]. Occupation-based splinting is defined as “attention to the occupational desires and needs of the individual, paired with the knowledge of the effects (or potential effect) of pathological conditions of the hand, and managed through client-centered splint design and provision” [Amini 2005, p. 11].

Prior to starting the splinting process, the therapist must adopt a personal philosophy that supports occupation-based and client-centered practice. Multiple models of practice exist that adopt this paradigm, including the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance (COPM), The Contemporary Task-Oriented Approach [Kamm et al. 1990], and the Model of Human Occupation and Occupational Adaptation [Law 1998]. In addition, the occupational therapist should understand the tenets of the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF) and its relationship to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF).

The profession of occupational therapy adopted the use of splints, an ancient technique of immobilization and mobilization, in the mid part of the twentieth century [Fess 2002]. According to Fess, the most frequently recorded reasons for splinting include increasing function, preventing deformity, correcting deformity, protecting healing structures, restricting movement, and allowing tissue growth or remodeling [Fess et al. 2005]. Such reasons for splinting relate to changing the condition of the neuro-musculoskeletal system and body functions within the client factors category of the OTPF. However, body components comprise only a part of the overall occupational behavior of the client, and despite the importance of assisting the healing or mobility of the hand the therapist must immediately and concurrently tend to the needs of the client that transcend movement and strength of the body.

This chapter provides definitions of client-centered and occupation-based practice. The process of combining both approaches to splinting is presented, with suggested assessment tools and treatment approaches that are compatible with such practice approaches. Splinting options that promote occupational functioning are described.

Client-Centered versus Occupation-Based Approaches

Client-centered and occupation-based practice are compatible, but a distinction is made between the two [Pierce 2003]. Client-centered practice is defined as “an approach to service which embraces a philosophy of respect for, and partnership with, people receiving services” [Law et al. 1995, p. 253]. Law [1998] outlined concepts and actions of client-centered practice, which articulate the assumptions for shaping assessment and intervention with the client (Box 2-1).

Occupation-based practice is “the degree to which occupation is used with reflective insight into how it is experienced by the individual, how it is used in natural contexts for that individual, and how much the resulting changes in occupational patterns are valued by the client” [Goldstein-Lohman et al. 2003]. Methods of employing empathy, reflection, interview, observation, and rigorous qualitative inquiry assist in understanding the occupations of others [Pierce 2003]. Christiansen and Townsend [2004] described occupation-based occupational therapy as an approach to treatment that serves to facilitate engagement or participation in recognizable life endeavors. Pierce [2003] described occupation-based treatment as including two conditions: (1) the occupation as viewed from the client’s perspective and (2) the occupation occurring within a relevant context. According to the OTPF, context relates “to a variety of interrelated conditions within and surrounding the client that influence performance” [AOTA 2002, p. 613]. Contexts include cultural, physical, social, personal, spiritual, temporal, and virtual aspects [AOTA 2002]. Thus, you should consider both factors when working with clients.Box 2-2 describes the contexts.

Occupation-Based Splint Design and Fabrication

Occupation-based splinting is a treatment approach that supports the goals of the treatment plan to promote the ability of clients to engage in meaningful and relevant life endeavors. Unlike a more traditional model of splinting that may initially focus on body structures and processes, occupation-based splinting incorporates the client’s occupational needs and desires, cognitive abilities, and motivation. When using occupation-based splinting, the therapist recognizes that the client is an active participant in the treatment and decision-making process [Amini 2005]. Splinting as occupation-based and client-centered treatment focuses on meeting client goals as opposed to therapist-designed or protocol-driven goals. Body structure healing is not the main priority. It is a priority equal to that of preservation of occupational engagement.

Occupation-based splinting can be viewed as part of a top-down versus bottom-up approach to occupational therapy intervention. According to Weinstock-Zlotnick and Hinojosa [2004], the therapist who engages in a top-down approach always begins treatment by examining a client’s occupational performance and grounds treatment in a client-centered frame of reference. A therapist who uses a bottom-up approach first evaluates the pathology and then attempts to connect the body deficiencies to performance difficulties. To be truly holistic, one must never rely solely on one method or frame of reference for treatment. Treating a client’s various needs is a first and foremost priority.

Occupation-Based Splinting and Contexts

According to the OTPF, occupational therapy is an approach that facilitates the individual’s ability to engage in meaningful activities within specific performance areas of occupation and varied contexts of living [AOTA 2002]. The performance areas of occupation define the domain of occupational therapy and include activities of daily living (ADLs), instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), leisure, play, work, education, and social participation [AOTA 2002]. Context is a strong component of occupational engagement that permeates all levels of treatment planning, intervention, and outcomes.

An often overlooked issue surrounding splinting is attention to the client’s cultural needs. Unfortunately, to ignore culture is to potentially limit the involvement of clients in their splint programs. For example, there are cultures whereby the need to rely on a splint is viewed as an admission of vulnerability or as a weakness in character. Such feelings can exist due to large group beliefs or within smaller family dynamic units. Splinting within this context must involve a great deal of client education and possibly education of family members. Issuing small, unobtrusive splints that allow as much function as possible may diminish embarrassment and a sense of personal weakness [Salimbene 2000].

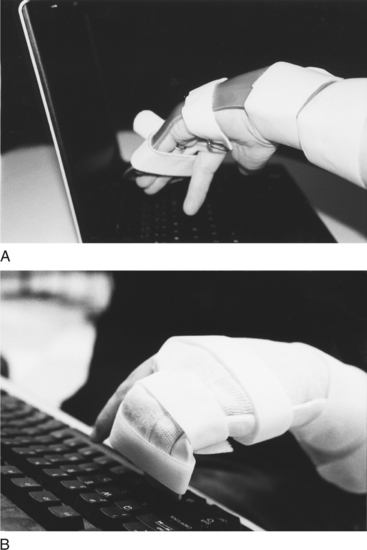

A knowledge of physical environments may contribute to an understanding of the need for splint provision. Physical environments may also hamper consistent use if clients are unable to engage in required or desired activities. For example, if a client needs to drive to work and is unable to drive while wearing a splint he might remove it despite the potential for reinjury.Figure 2-1A depicts a young woman wearing a splint because she sustained a flexor digitorum profundus injury. She found that typing at her workplace while wearing the splint was creating shoulder discomfort. She asked the therapist if she could remove her splint for work, and with physician approval the therapist created a modified protective splint (Figure 2-1B). The newly modified splint allowed improved function and protected the healing tendon.

Figure 2-1 (A) Excessive pronation required to accurately press keys while using standard dorsal blocking splint. (B) Improved ability to work on computer using modified volar-based protective splint.

Social contexts pertain to the ability of clients to meet the demands of their specific group or family. Social contexts are taken into consideration with splint provision. For example, a new mother is recently diagnosed with de Quervain’s tenosynovitis and is issued a thumb splint. The mother feels inadequate as a mother when she cannot cuddle and feed the infant without contacting the infant with a rigid splint. In such a case, a softer prefabricated splint or alternative wearing schedule is suggested to maximize compliance with the splint program (Figure 2-2).

Personal context involves attention to such issues as age, gender, and educational and socioeconomic status. When clinicians who employ occupation-based splinting fabricate splints for older adults or children, they consider specific guidelines (see Chapters 15 and 16). The choices in material selection and color may be different based on age and gender. For example, a child may prefer a bright-colored splint whereas an adult executive may prefer a neutral-colored splint. Concerns may arise about the role educational level plays in splint design and provision. For clients who have difficulty understanding new and unfamiliar concepts, it is important to have a splint that is simple in design and can be donned and doffed easily. Precautions and instructions should be given in a clear manner.

Although it is typically considered a cognitive function, expression of spirituality can be potentially affected by changes to the physical body. For example, some clients are not able to pray or to attend religious services because parts of their bodies are restricted by splints. All clients should be asked if their splints are in any way inhibiting their ability to engage in any life experience. Almost all splints affect a person’s ability to perform activities. The impact is a matter of degree, and consideration needs to be given to the tradeoff between how it enables clients (if only in the future) and how it disables them. Therapists must be aware of the balance between enablement and disablement and do their best to appropriately modify the splint or the wearing schedule or to provide an adaptation to facilitate clients’ occupational engagement.

Temporal concerns are addressed through attention to issues such as comfort of the splint during hot summer months or the use of devices during holidays or special events such as proms or weddings. An example is the case of a bride-to-be who was two weeks postoperative for a flexor tendon repair of the index finger. The young woman asked repeatedly if she could take off her splint for one hour during her wedding. A compromise reached between the therapist and the client ensured that her hand would be safe during the ceremony. A shiny new splint was made specifically for her wedding day to immobilize the injured finger and wrist (modified Duran protocol). The therapist discarded the rubber-band/finger-hook component (modified Kleinert protocol). This change made the splint smaller and less obvious. The client was a happy bride and her finger was well protected.

Virtual context addresses the ability to access and use electronic devices. The ability to access devices (e.g., computers, radios, PDAs, MP3 players, cell phones) plays an important role in many people’s lives. Fine motor control is paramount when using these devices and should be preserved as much as possible to maximize electronic contact with the outside world. Attention to splint size and immobilizing only those joints required can facilitate the ability of clients to manipulate small buttons and dials required to use such devices. “While use of a keyboard tends to be a bilateral activity, many devices (such as radios, PDAs, and cell phones) do not require bilateral fine motor skill. As technology improves with cordless and voice-activated systems, the needs for fine motor skill in operation of some electronic devices may decrease. A therapist is the ideal person to introduce this technology to the client” [personal communication, K. Schultz-Johnson, October 5, 2005].

For a splint to be accepted as a legitimate holistic device, it must work for the client within the context(s). Splints might perpetuate dysfunction and may prolong the return to meaningful life engagement without attention to the specifics of how and where clients live their lives. To ignore the interconnection of function to where and how function plays out is to practice a reductionist form of treatment that emphasizes isolated skills and body structures, without regard to clients’ engagement in selected activities.

Occupation-Based Splinting and Intervention Levels

Pedretti and Early [2001] described four intervention levels: adjunctive, enabling, purposeful activities, and occupations. Adjunctive methods prepare clients for purposeful activity and they do not imply activity or occupation. Examples include exercise, inhibition or facilitation techniques, and positioning devices. Enabling activities precede and simulate purposeful activity. For example, simulated activities (e.g., driving simulators) begin to prepare the client for participation in actually driving a vehicle. Purposeful activities are goal directed and have meaning and purpose to the client. In the case of driving, when a client actually gets into a vehicle and drives, the intervention level is considered purposeful activity. Occupation is the highest level of intervention. Clients participate in occupations in their natural context. The ability to drive to one’s employment site is considered an occupation.

At first blush, splinting could appear to be less than occupation oriented because it is initiated prior to occupational engagement and discontinued when hand function resumes. From an occupation-based perspective, splinting is not a technique used only in preparation for occupation. For appropriate clients, splints are an integral part of ongoing intervention to support occupational engagement at all levels of intervention: adjunctive, enabling, purposeful activity, and occupation. For example, some clients may receive a splint to decrease pain while simultaneously being allowed engagement in work and leisure pursuits.

Splinting as a Therapeutic Approach

The OTPF intervention approaches are defined as “specific strategies selected to direct the process of intervention that are based on the client’s desired outcome, evaluation data and evidence” [AOTA 2002, p. 632]. These treatment approaches include processes to (1) create or promote health, (2) establish or restore health, (3) maintain health, (4) modify through compensation and adaptation, and (5) prevent disability [AOTA 2002].

From an occupation-based perspective, when splints enable occupation it seems to elevate splint status to that of an integral approach to treatment versus an adjunctive technique. Custom fitted splints within the context of clients’ occupational experience can promote health, remediate dysfunction, substitute for lost function, and prevent disability. When teamed with a full occupational analysis and knowledge of the appropriate use of splints for specific pathologies (supported by evidence of effectiveness), splinting options are selected to produce the outcomes that reach the goals collaboratively set by the client and the practitioner.

Splinting as a Facilitator of Therapeutic Outcomes

Within the context of occupation-based practice, splinting is a therapeutic approach interwoven through all levels of intervention. Splinting is a facilitator of purposeful and occupation-based activity. The OTPF describes specific therapeutic outcomes expected of intervention. Outcomes are occupational performance, client satisfaction, role competence, adaptation, health and wellness, prevention, and quality of life [AOTA 2002]. Positive outcomes in occupational performance are the effect of successful intervention. Such outcomes are demonstrated either by improved performance within the presence of continued deficits resulting from injury or disease or the enhancement of function when disease is not currently present.

Splinting addresses both types of occupational performance outcomes (improvement and enhancement). Splints that improve function in a person with pathology result in an “increased independence and function in an activity of daily living, instrumental activity of daily living, education, work, play, leisure, or social participation” [AOTA 2002, p. 628]. For example, a wrist immobilization splint is prescribed for a person who has carpal tunnel syndrome. The splint positions the wrist to rest the inflamed anatomical structures, thus decreasing pain and work performance improves. Splints that enhance function without specific pathology result in improved occupational performance from one’s current status or prevention of potential problems. For example, some splints position the hands to prevent overuse syndromes resulting from hand-intensive repetitive or resistive tasks.

Satisfaction of the entire therapeutic process is increased when the client’s needs are met. When clients are included as an integral part of the splinting process, they are more likely to comply and to use the splint. Inclusion of clients in treatment planning is important to creating splints that minimally inhibit function and take the client’s lifestyle into consideration.

Role competence is the ability to satisfactorily complete desired roles (e.g., worker, parent, spouse, friend, and team member). Roles are maintained through splinting by minimizing the effects of pathology and facilitating upper extremity performance for role-specific activities. For example, a mother who wears a splint for carpal tunnel syndrome should be able to hold her child’s hand without extreme pain. Holding the child’s hand makes her feel like she is fulfilling her role as a mother.

Splints created to enhance adaptation to overcome occupational dysfunction address the dynamics of the challenges and the client’s expected ability to overcome it. An example of splinting to improve adaptation might involve a client who experiences carpal ligament sprain but must continue working or risk losing employment. In this case, a wrist immobilization splint that allows for digital movements may enable continued hand functions while resting the involved ligament.

Health and wellness are collectively described as the absence of infirmity and a “state of physical, mental, and social well-being” [AOTA 2002, p. 628]. Splinting promotes health and wellness of clients by minimizing the effects of physical disruption through protection and substitution. Enabling a healthy lifestyle that allows clients to experience a sense of wellness facilitates motivation and engagement in all desired occupations [Christiansen 2000].

Prevention in the context of the OTPF involves the promotion of a healthy lifestyle at a policy creation, organizational, societal, or individual level [AOTA 2002]. When an external circumstance (e.g., environment, job requirement, and so on) exists with the potential for interference in occupational engagement, a splinting program may be a solution to prevent the ill effects of the situation. If it is not feasible to modify the job demands, clients may benefit from the use of splints in a preventative role. For example, a wrist immobilization splint and an elbow strap are fitted to prevent lateral epicondylitis of the elbow for a client who works in a job that involves repetitive and resistive lifting of the wrist with a clenched fist. In addition, the worker is educated on modifying motions and posture that contribute to the condition.

Of great concern is the concept of quality of life [Sabonis-Chafee and Hussey 1998]. Although listed as a separate therapeutic outcome within the OTPF, quality of life is a subjective state of being experienced by clients. Quality of life entails one’s appraisal of abilities to engage in specific tasks that beneficially affect life and allow self-expressions that are socially valued [Christiansen 2000]. One’s state of being is determined by the ability of the client to be satisfied, engage in occupations, adapt to novel situations, and maintain health and wellness. Ultimately, splinting focused on therapeutic outcomes will improve the quality of life through facilitating engagement in meaningful life occupations.

The Influence of Occupational Desires on Splint Design and Selection

The occupational profile phase of the evaluation process described in the OTPF involves learning about clients from a contextual and performance viewpoint [AOTA 2002]. For example, what are the interests and motivations of clients? Where do they work, live, and recreate? Tools (i.e., Canadian Occupational Performance Model; Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand; and the Patient-Rated Wrist Hand Evaluation) that offer clients the opportunity to discuss their injuries in the context of their daily lives lend insight into the needs that must be addressed.Table 2-1 lists such tools. When used in conjunction with traditional methods of hand and upper extremity assessment (e.g., goniometers, dynamometers, and volumeters), they help therapists learn about the specific clients they treat and assist in splint selection and design.

Table 2-1

| TOOL | GENERAL DESCRIPTION | CONTACT INFORMATION |

| Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) [Law et al. 1994] | The COPM is a client-centered approach to assessment of perceived functional abilities, interest, and satisfaction with occupations. This interview-based valid and reliable tool is scored and can be used to measure outcomes of treatment. | The COPM can be purchased through the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists at http://www.caot.ca. |

| Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) assessment [Hudak et al. 1996] | DASH is a condition-specific tool. The DASH consists of 30 predetermined questions addressing function within performance areas. Clients are asked to rate their recent ability to complete skills on a scale of 1 (no difficulty) to 5 (unable). The DASH assists with the development of the occupational profile through its valid and reliable measure of clients’ functional abilities. | DASH/QuickDASH web site at http://www.dash.iwh.on.ca. |

| Patient-Rated Wrist/Hand Evaluation (PRWHE) [MacDermid and Tottenham 2004] | The PRWHE is a condition-specific tool through which the client rates pain and function in 15 preselected items. | MacDermid JC, Tottenham V (2004). Responsiveness of the disability of the arm, shoulder, and hand (DASH) and patient-rated wrist/hand evaluation (PRWHE) in evaluating change after hand therapy. Journal of Hand Therapy 17:18-23. |

The assessment tools listed inTable 2-1 emphasize client occupations and functions as the focus of intervention. Information obtained from such assessments supports the goal of occupation-based splinting, which is to improve the client’s quality of life through the client’s continued engagement in desired occupations.

A splint that focuses on client factors alone does not always treat the functional deficit. For example, a static splint to support the weak elbow of a client who has lost innervation of the biceps muscle protects the muscle yet allows only one angle of function of that joint. A dynamic flexion splint protects the muscle from end-range stretch yet allows the client the ability to change the arm angle through active extension and passive flexion. Assessment tools that measure physical client factors exclusively (e.g., goniometry, grip strength, volumeter, and so on) must remain as adjuncts to determine splint design because physical functioning is an adjunct to occupational engagement.

Canadian Occupational Performance Measure

The COPM is an interview-based assessment tool for use in a client-centered approach [Law et al. 1994]. The COPM assists the therapist in identifying problems in performance areas, such as those described by the OTPF. In addition, clients’ perceptions of their ability to perform the identified problem area and their satisfaction with their abilities are determined when using the COPM [Law et al. 1994]. A therapist can use the COPM with clients from all age groups and with any type of disability. Parents or family members can serve as proxies if the client is unable to take part in the interview process (e.g., if the client has dementia). When the COPM is readministered, objective documentation of the functional effects of splinting through comparison of pre- and post-intervention scores is made.

When using the COPM, contextual issues will arise during the client interview about satisfaction with function. Clients may indicate why certain activities create personal dissatisfaction despite their ability to perform them. An example is the case of a woman who resides in an assisted living setting. During administration of the COPM, she identifies that she is able to don her splint by using her teeth to tighten and loosen the straps. She needs to remove the splint to use utensils during meals. However, she is embarrassed to do this in front of other residents while at the dining table. The use of the COPM uncovers issues that are pertinent to individual clients and must be considered by the therapist.

Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand

The Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) is a condition-specific tool that measures a client’s perception of how current upper extremity disability has impacted function [DASH 2005]. The DASH consists of 30 predetermined questions that explore function within performance areas. The client is asked to rate on a scale of 1 (no difficulty) to 5 (unable) his or her current ability to complete particular skills, such as opening a jar or turning a key. The DASH assists the therapist in gathering data for an occupational profile of functional abilities. The focus of the assessment is not on body structures or on the signs and symptoms of a particular diagnostic condition. Rather, the merit of the DASH is that the information obtained is about the client’s functional abilities.

An interview, although not mandated by the DASH, should become part of the process to enhance the therapist’s understanding of the identified problems. The therapist must also determine why a functional problem exists and how it may be affecting quality of life. The DASH is an objective means of measuring client outcomes when readministered following splint provision or other treatment interventions [Beaton et al. 2001].

When selecting the DASH as a measure of occupational performance, the therapist may consider several additional facts. For example, the performance areas measured are predetermined in the questionnaire and may limit the client’s responses. In addition, the DASH does not specifically address contextual issues or client satisfaction or provide insight into the emotional state of the client. Additional information can be obtained through interview to gain insight needed for proper splint design and selection.

Patient-Rated Wrist Hand Evaluation

The Patient-Rated Wrist Hand Evaluation (PRWHE) is a condition-specific tool through which clients rate their pain and functional abilities in 15 preselected areas [MacDermid and Tottenham 2004]. PRWHE assists with the development of the occupational profile through obtaining information about clients’ functional abilities. The functional areas identified in the PRWHE are generally much broader than those in the DASH. Similar to the DASH, the PRWHE’s questions to elicit such information are not open-ended questions as in the COPM. Information about pain levels during activity and client satisfaction of the aesthetics of the upper limb are gathered during the PRWHE assessment.

The PRWHE does not specifically require an inquiry into the details of function, but such information would certainly assist the therapist and make the assessment process more occupation based. The PRWHE does not include questions related to context. Therefore, the therapist should include such questions in treatment planning discussions.

Following the data collection part of the evaluation process, the analysis of occupational performance can occur. If a therapist uses one of the aforementioned tools, analysis of the performance process has been initiated. Further questions will be asked based on the answers of previous questions. The therapist continues to gain specific insight into how splinting can be used to remediate the reported dysfunction.

During the analysis phase, the therapist may actually want to see the client perform several functions to gain additional insight into how activity affects, or is impacted by, the diagnosis or pathology. For example, a client states that he cannot write because of thumb carpometacarpal (CMC) joint pain. Therefore, the therapist asks the client to show how he is able to hold the pen while describing the type of discomfort experienced while writing. The therapist may begin splint design analysis by holding the client’s thumb in a supported position to simulate the effect of a hand-based splint. The client will actively participate in the process by giving feedback to the therapist during splint design and fabrication.

After a client-centered occupation-based profile and analysis is completed, an occupation-based splinting intervention plan is developed. Measuring only physical factors to create a client profile will result in a therapist seeing only the upper extremity and not the client. The upper extremity does not dictate the quality of life. Rather, the mind, spirit, and body do so collectively! (See Self-Quiz 2-1.)

Evidence to Support Preservation of Occupational Engagement and Participation

Fundamental to occupational therapy treatment is the belief that individuals must retain their ability to engage in meaningful occupations or risk further detriment to their subjective experience of quality of life. If humans behaved as automatons–completing activities without drive, interest, or attention–correcting deficits would become reductionist and mechanical. A reductionistic approach could guarantee that an adaptive device or exercise could correct any problem and immediately lead to the continuation of the required task (much like replacing a spark plug to allow a car to start). Fortunately, humans are not automatons and occupational therapy exists to support the ability of the individual to engage in and maintain participation in desired occupations.

The literature supports the premise that any temporary or permanent disruption in the ability to engage in meaningful occupations can be detrimental [Christiansen and Townsend 2004]. For example, with a flexor tendon repair therapists must follow protocols to facilitate appropriate tissue healing. Such a protocol typically removes the hand from functional pursuits for a minimum of six to eight weeks. However, occupational dysfunction must be effectively minimized as soon as possible to maintain quality of life [McKee and Rivard 2004].

Evidence to Support Occupational Engagement

Supported by research, in addition to anecdotal experiences and reports of therapists, is the importance of multidimensional engagement in meaningful occupations. Originally described by Wilcock [1998], the term occupational deprivation is a state wherein clients are unable to engage in chosen meaningful life occupations due to factors outside their control. Disability, incarceration, and geographic isolation are but a few circumstances that create occupational deprivation. Depression, isolation, difficulty with social interaction, inactivity, and boredom leading to a diminished sense of self can result from occupational deprivation [Christiansen and Townsend 2004]. Occupational disruption is a temporary and less severe condition that is also caused by an unexpected change in the ability to engage in meaningful activities [Christiansen and Townsend 2004]. Additional studies conducted by behavioral scientists interested in how individual differences, personality, and lifestyle factors influence well-being have shown that engagement in occupations can influence happiness and life satisfaction [Christiansen et al. 1999].

Ecological models of adaptation suggest that people thrive when their personalities and needs are matched with environments or situations that enable them to remain engaged, interested, and challenged [Christiansen 1996]. Walters and Moore [2002] found that among the unemployed, involvement in meaningful leisure activities (not simply busy-work activities) decreased the sense of occupational deprivation.

Palmadottir [2003] completed a qualitative study that explored clients’ perspectives on their occupational therapy experience. Positive outcomes of therapy were experienced by clients when treatment was client centered and held purpose and meaning for them. Thus, when a client who has an upper extremity functional deficit receives a splint the splint should meet the immediate needs of the injury while meeting the client’s desire for occupational engagement.

According to Ludwig [1997], consistency and routine help older adult women maintain the ability to meet their obligations and maintain activity levels and overall health. In addition, routines control and balance ADLs, self-esteem, and intrinsic motivation for activities. Such consistency and routine can be maintained through splinting techniques that allow function while simultaneously decreasing the effects of pathology.

Research offers evidence that splints of all types and for all purposes are indeed effective in reaching the goals of improved function [Dunn et al. 2002, Li-Tsang et al. 2002, Schultz-Johnson 2002, Werner et al. 2005]. Four examples are presented to demonstrate such evidence. A study was conducted on the effects of splinting dental hygienists who had osteoarthritis. The researchers indicated that such splints can reduce the effect of pain on thumb function [Dunn et al. 2002]. Schultz-Johnson [2002] concluded that static progressive splints improve end-range motion and passive movements that cannot be obtained in any other way. Such splints make a difference in the lives of clients.

Li-Tsang et al. [2002] found splinting of finger flexion contractures caused by rheumatoid arthritis to be effective. Clients experienced statistically significant improvements in the areas of hand strength (pinch and grip) and active range of motion in both extension and flexion after a program of splinting [Li-Tsang et al. 2002]. Nocturnal wrist extension splinting was found to be effective in reducing the symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome experienced by Midwestern auto assembly plant workers [Werner et al. 2005]. This evidence leads us to conclude that splinting with attention to occupational needs can and should be used to preserve quality of life.

Utilizing an Occupation-Based Approach to Splinting

With guiding philosophies in place, the therapist using an occupation-based approach to splinting will begin the following problem-solving process of splint design and fabrication.

Step 1: Referral

The clinical decision-making process begins with the referral. Some splint referrals come from physicians who specialize in hand conditions. A referral may contain details about the diagnosis or requested splint. However, some orders may be from physicians who do not specialize in the treatment of the hand. If this is the case, the physician may depend on the expertise of the therapist and may simply order a splint without detailing specifics. An order to splint a client with a condition may also rely on the knowledge and creativity of the therapist. At this step, the therapist must begin to consider the diagnosis, the contextual issues of the client, and the type of splint that must be fabricated.

Step 2: Client-Centered Occupation-Based Evaluation

Therapists use assessments such as the COPM, DASH, or PRWHE to learn which occupations the client desires to complete during splint wear, which occupations splinting can support, and which occupations the splint will eventually help the person accomplish. The therapist and the client use this information for goal prioritization and splint design in step 4.

Step 3: Understand/Assess the Condition and Consider Treatment Options

Review biology, cause, course, and traditional treatment of the person’s condition, including protocols and healing timeframes. Assess the client’s physical status. Research splint options and determine possible modifications to result in increased occupational engagement without sacrificing splint effectiveness. When a splint is ordered to prevent an injury, the therapist must analyze any activities that may be impacted by wearing the splint and determining how it may affect occupational performance.

Step 4: Analyze Assessment Findings for Splint Design

Analyze information about pathology and protocols to reconcile needs of tissue healing and function (occupational engagement). Consider whether the condition is acute or chronic. Acute injuries are those that have occurred recently and are expected to heal within a relatively brief time period. Acute conditions may require splinting to preserve and protect healing structures. Examples include tendon or nerve repair, fractures, carpal tunnel release, de Quervain’s release, Dupuytren’s release, or other immediate post-surgical conditions requiring mobilization or immobilization through splinting.

If the condition is acute, splint according to protocols and knowledge of client occupational status and desires. Determine if the client is able to engage in desired occupations within the splint. If the client can engage in occupations while wearing the splint, continue with a custom occupation-based treatment plan in addition to splinting.

Step 5: Determining Splint Design

If the client is unable to complete desired activities and functions within the splint, the therapist must determine modifications or alternative splint designs to facilitate function. Environmental modifications or adaptations may be needed to accommodate lack of function if no further changes can be made to the splint.

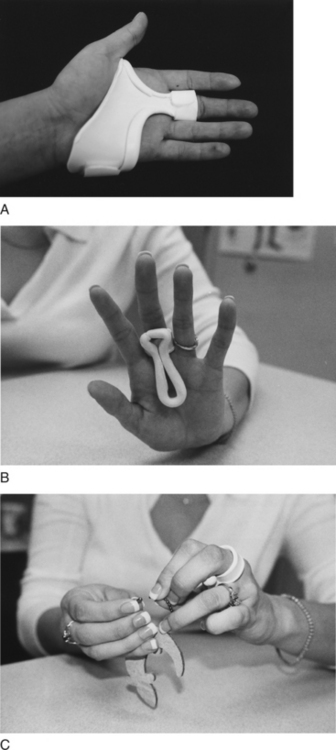

Figure 2-3A is an example of a hand-based trigger finger splint that allows unrestricted ability of the client to engage in a craft activity. Compare the splint shown inFigure 2-3B to the splint (shown inFigure 2-3C) previously issued, which limited mobility of the ulnar side of the hand and diminished comfort and activity satisfaction.

Figure 2-3 (A) Confining hand-based trigger finger splint. (B) Finger-based MP blocking trigger finger splint. (C) Functional ability while using finger-based trigger finger splint.

To ensure that an occupation-based approach to splinting has been undertaken, the occupation-based splinting (OBS) checklist can be used (Form 2-1). This checklist focuses the therapist’s attention on client-centered occupation-based practice. Using the checklist helps ensure that the client does not experience occupational deprivation or disruption.

Splint Design Options to Promote Occupational Engagement and Participation

The characteristics of a splint will have an influence on a client’s ability to function. The therapist faces the challenge of trying to help restore or protect the client’s involved anatomic structure while preserving the client’s performance. To achieve optimal occupational outcomes, specific designs and materials must be used to fabricate splints that are user friendly. The therapist must employ clinical reasoning that considers the impact on the injured tissue and the desires of the client. Such consideration will result in a splint that best protects the anatomic structure at the same time it preserves the contextual and functional needs of the client.

Summary

Engagement in relevant life activities to enhance and maintain quality of life is a concept to be considered with splint provision. The premise that splinting the hand and upper extremity can improve the overall function of the hand is supported in the literature. Hence, splinting that includes attention to the functional desires of the client is a valid occupation-based treatment approach that enhances life satisfaction and facilitates therapeutic outcomes.

1. According to this chapter, what is the definition of occupation-based splinting?

2. According to Fess [2002], what are the reasons therapists provide splints to clients who have upper extremity pathology?

3. Why is it important for the client to be an active participant in the splinting process?

4. Why is attention to the context of the client integral to occupation-based splinting?

5. Why should a therapist be knowledgeable about tissue healing and treatment protocols despite the fact that such factors do not imply occupation-based treatment?

References

American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2002;56:609–639.

Amini, D. The occupational basis for splinting. Advance for Occupational Therapy Practitioners. 2005;21:11.

Beaton, DE, Katz, JN, Fossel, AH, Wright, JG, Tarasuk, V, Bombardier, C. Measuring the whole or parts? Validity, reliability and responsiveness of the disabilities of the arm, shoulder, and hand outcome measure in different regions of the upper extremity. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2001;14:128–146.

Christiansen, C. Three perspectives on balance in occupation. In: Zemke R, Clark F, eds. Occupational Science: The Evolving Discipline. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis; 1996:431–451.

Christiansen, C. Identity personal projects, and happiness: Self construction in everyday action. Journal of Occupational Science. 2000;7:98–107.

Christiansen, C, Backman, C, Little, B, Nguyen, A. Occupations and subjective well-being: A study of personal projects. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1999;53:91–100.

Christiansen, C, Townsend, E. Introduction to Occupation: The Art and Science of Living. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2004.

DASH Outcome Measure, Institute for Work and Health. Retrieved February 13, 2005, from www.dash.iwh.on.ca.

Dunn, J, Pearce, O, Khoo, CTK. The adventures of a hygienist’s hand: A case report and surgical review of the effects of osteoarthritis. Dental Health. 2002;41:6–9.

Fess, E. A history of splinting: To understand the present, view the past. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2002;15:97–132.

Fess, EE, Gettle, KS, Philips, CA, Janson, JR. Hand and Upper Extremity Splinting: Principles and Methods, Third Edition. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby, 2005.

Goldstein-Lohman, H, Kratz, A, Pierce, D. A study of occupation-based practice. In: Pierce D, ed. Occupation by Design: Building Therapeutic Power. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis; 2003:239–261.

Kamm, K, Thelen, E, Jensen, JL. A dynamical systems approach to motor development. Physical Therapy. 1990;70:763–775.

Law M, ed. Client-Centered Occupational Therapy. Thorofare, NJ: Slack, 1998.

Law, M, Baptiste, S, Carswell, A, McCall, MA, Polatajko, H, Pollock, N. Canadian Occupational Performance Measure. Ottawa, ON: CAOT, 1994.

Law, M, Baptiste, S, Mills, J. Client-centered practice: What does it mean and does it make a difference? Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1995;62:250–257.

Li-Tsang, C, Hung, L, Mak, A. The effect of corrective splinting on flexion contracture of rheumatoid fingers. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2002;15:185–191.

Ludwig, F. How routine facilitates wellbeing in older women. Occupational Therapy International. 1997;4:213–228.

MacDermid, J, Tottenham, V. Responsiveness of the disability of the arm, shoulder and hand (DASH) and patient-rated wrist/hand evaluation (PRWHE) in evaluating change after hand therapy. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2004;17:18–23.

McKee, P, Rivard, A. Orthoses as enablers of occupation: Client-centered splinting for better outcomes. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2004;71:306–314.

Palmadottir, G. Client perspectives on occupational therapy in rehabilitation services. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2003;10:157–166.

Pedretti, LW, Early, MB. Occupational performance and models of practice for physical dysfunction. In: Pedretti LW, Early MB, eds. Occupational Therapy Practice Skills for Physical Dysfunction. St. Louis: Mosby; 2001:3–12.

Pierce, D. Occupation by Design: Building Therapeutic Power. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 2003.

Reilly, M. Occupational therapy can be one of the great ideas of 20th century medicine. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1962;16:2.

Sabonis-Chafee, B, Hussey, S. Introduction to Occupational Therapy, Second Edition. St. Louis: Mosby, 1998.

Salimbene, S. What Language Does Your Patient Hurt In? St. Paul, MN: EMCParadigm, 2000.

Schultz-Johnson, K. Static progressive splinting. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2002;15:163–178.

Walters, L, Moore, K. Reducing latent deprivation during unemployment: The role of meaningful leisure activity. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2002;75:15–18.

Weinstock-Zlotnick, G, Hinojosa, J. Bottom-up or top-down evaluation: Is one better than the other? American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2004;58:594–599.

Werner, R, Franzblau, A, Gell, N. Randomized controlled trial of nocturnal splinting for active workers with symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2005;86:1–7.

Wilcock, A. An Occupational Perspective of Health. Thorofare, NJ: Slack, 1998.