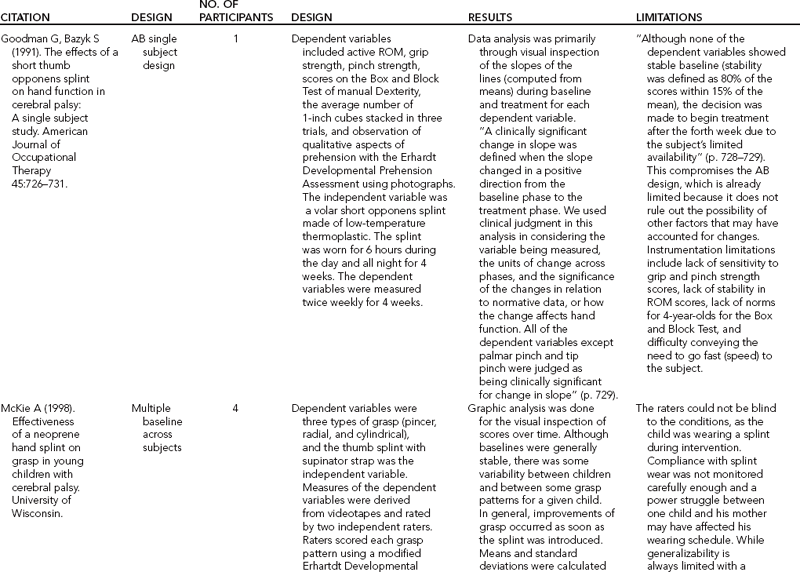

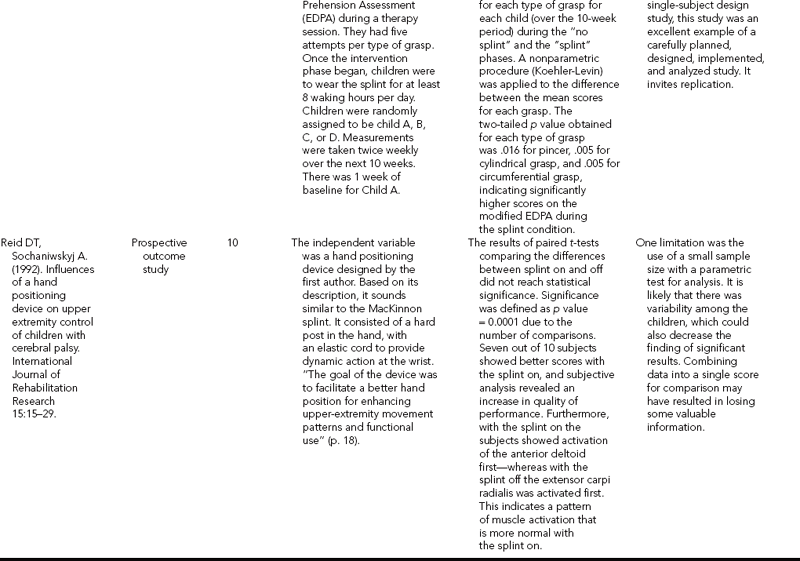

Pediatric Splinting

1 Identify the characteristics of children who need orthotic intervention.

2 Explain the impact of upper extremity splinting on the development of childhood occupations.

3 Describe the major features and purposes of a resting hand splint, wrist splints, thumb splints, serpentine splints, and weight-bearing splints.

4 Describe the process for fabricating each of these splints, as well as individual variations.

5 Identify resources for the purchase of prefabricated pediatric splints.

6 Explain precautions for these splints and their variations.

7 Justify an effective and reasonable wearing schedule.

8 Explain how to provide instructions to care providers to maximize correct application and usage of the splints.

9 Judge when a splint is fitting properly and identify and correct errors in the fit of a splint.

10 Examine evidence for splinting children and recommend future areas of needed research.

This chapter presents applications of general splinting principles to the selection, design, fabrication, or purchase of several basic hand splints. The splints presented in this chapter should be used as part of a comprehensive treatment program for children with a focus on children with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies. Like splints for adults, splints for children may be used to prevent deformity, to increase function, or to do both. However, splinting children involves more than just making a smaller splint pattern. The purpose of this chapter is to guide the beginning therapist in applying splinting knowledge to the special needs of children with developmental disabilities or birth defects of a neurologic or orthopedic nature, such as cerebral palsy or arthrogryposis multiplex congenita.

The resting hand, weight-bearing, wrist, thumb, and serpentine splints represent basic designs that are the focus of this chapter. In practice, the therapist should consider modifying these designs or creating entirely new ones to ensure that they meet the needs of an individual child. The therapist may use a single splint for a child or fabricate two splints for a child, which are worn alternately. For example, this alternate schedule is appropriate for children who have some functional use of their hands but are also at risk of developing contractures.

It may not be possible or desirable to accomplish all of the splinting goals with one splint. Attempting to do so may not meet any of the stated goals [Exner 2005]. Children with severe or complex hand problems may require a series of splints that addresses the most pressing needs first or that is serial in nature, with each new splint coming closer to the desired end product.

Before splinting decisions can be made, the therapist must establish overall treatment goals based on a frame of reference appropriate to the child and the environment. The splint, if appropriate, then becomes a component of this treatment program—which also includes goals for improving function and the child’s ability to participate in childhood occupations (including play, self-care, and such productive activities as schoolwork). Splint designs in this chapter are compatible with neurodevelopmental treatment, rehabilitative, and/or biomechanical frames of reference. Splinting decisions must also be compatible with the lifestyle, values, and culture of the child and the family—as well as with the child’s home, day care, community, and school environments.

Because the purpose of this chapter is to introduce basic concepts to beginning splinters, there are many types and variations of pediatric hand splints that will not be covered. A number of children may respond best to a splint designed to reduce spasticity (see Chapter 14). Children with traumatic injuries or burns can be approached in a manner similar to adults [Hogan and Uditsky 1998], which is described in previous chapters. Other children may benefit from the use of plaster or pneumatic splints for the elbow or hand (see Chapter 14). Some splints are part of interventions in advanced areas of practice, such as the neonatal intensive care unit. These complex or specialized splints are beyond the scope of this chapter. Readers are encouraged to read articles cited in the references at the end of this chapter for more information. Those who desire additional skills in these areas should explore continuing education courses or arrange for advanced study.

The previous chapters have described basic splinting principles, designs, and fabrication techniques that need not be repeated here. However, examples and applications in previous chapters focused primarily on adults. Successfully splinting a child is different from splinting an adult in many respects, including the following:

• Abnormal muscle tone has been present since birth or infancy and may differ qualitatively from abnormal muscle tone acquired after disease or injury.

• The child experiences the dynamic process of maturational and neurologic development, which has a continuous effect on the acquisition of functional hand skills. It is also important to realize that because of the plasticity and immaturity of the child’s systems inappropriate splints can result in harmful effects [Granhaug 2006].

• Muscles and tendons undergoing growth respond differently to stretch [Wilton 2003].

• Children experience continued growth of the upper extremities. As children grow, splints fit tighter and create pressure. During a growth spurt, the risk of deformity or skin breakdown may increase as a result of bone growth that exceeds growth or lengthening of muscles and soft tissues because of spasticity. Deformity may also occur secondary to a splint that has been outgrown and no longer fits properly.

• Many children must rely on adults, such as parents or teachers, to apply and remove their splints. Therefore, the level of understanding and cooperation of these adults is a factor.

• Children have a low tolerance for interference by adults and the imposition of a piece of equipment (splint) unfamiliar to them. Their cognitive level may be insufficient for them to understand abstract concepts such as prevention or to comprehend cause-and-effect relationships (if you wear this splint, then your hand will work better). They may resist holding still, become fearful and cry, or be able to cooperate only for brief periods of time because of a short attention span. Any or all of these factors may create greater challenges to the fabrication and application of the splint(s) for children. In addition, as the child asserts his or her autonomy, a power struggle may develop with adults and the child may resist donning or removal of the splint at home or school.

• The placement and molding of a splint on a child is more difficult than on an adult because the child’s hand is much smaller in proportion to the therapist’s hand.

Diagnostic Indications

The focus of this chapter is on splinting the child with a developmental disability or congenital anomaly. However, many of the principles and splints described also apply to adults with developmental disabilities. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), developmental disabilities are a diverse group of chronic conditions that result from a mental and/or physical impairment and interfere with major life activities [CDC 2006]. Many developmental disabilities, such as cerebral palsy, are accompanied by central nervous system dysfunction and abnormal muscle tone.

Central nervous system dysfunction can be the result of many types of brain injury, such as an intracranial hemorrhage, hypoxia, infections, tumors, or trauma. Abnormal muscle tone can include increased, decreased, or fluctuating tone and presents a number of splinting challenges. Lower motor neuron dysfunction may also occur at birth as the result of excessive stretch to the brachial plexus during delivery. Depending on the nature and extent of the nerve damage, this may result in developmental arm and hand dysfunction.

Other diagnoses in children for which splinting may be indicated include brachial plexus injury or congenital defects or anomalies of the hand or upper extremity, which are generally due to malformations of the musculoskeletal system. Malformations include finger flexion contractures, soft-tissue or bony fusion (syndactyly), and dysplasia of the ulna or radius. Children with brachial plexus injury (Erb’s palsy) may require splinting or casting of the hand and the entire upper extremity, especially after surgery. Another congenital or birth defect that may require orthotic intervention is arthrogryposis multiplex congenita.

According to Banker, “Arthrogryposis multiplex congenita is not a specific disorder but rather a symptom complex of congenital joint contractures associated with both neurogenic and myopathic disorders.…The main feature shared by these disorders appears to be the presence of severe weakness early in fetal development, which immobilizes joints, resulting in contractures” [Banker 1985, p. 30]. Programs that involve early passive stretching and serial splinting of contracted joints are recommended [Bayne 1986, Donohoe 2006, Palmer et al. 1985, Sala et al. 1996, Williams 1985]. Splints, such as a dynamic elbow flexion splint, have also been developed to compensate for lost muscle power [Kamil and Correia 1990].

Children with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies often present with indwelling thumbs (thumbs held adducted into the palm). This may be the result of abnormal muscle tone, weakness, or abnormal anatomy of the hand. To effectively grasp and manipulate objects, it is crucial that the thumb be positioned in opposition. Splinting, along with active movement, is often required to effectively position the thumb in opposition for grasp and optimal hand function.

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) is a systemic rheumatic disease that causes major disabilities in children younger than 16 years. Children with JRA may present with pain, fatigue, and reduced range of motion (ROM). These symptoms often result in difficulty performing school tasks and activities of daily living. In addition to medical management and interventions to promote participation, treatment for JRA may include splinting and passive and active ranging of the joints [Rogers 2005]. In summary, a number of pediatric diagnoses may indicate a need for splinting. However, rather than strictly on a specific diagnosis the final splinting decision is made on the basis of the limitations in specific movements, the type and severity of abnormal muscle tone, the extent of soft-tissue and bony involvement, the child’s functional level, the child’s environment, and the frame of reference guiding therapy.

Assessment

Before fabricating a splint, the therapist must complete a comprehensive assessment. According to the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) Occupational Therapy Performance Framework, the therapist should consider performance in areas of occupation first and then evaluate performance skills, performance patterns, context, activity demands, and client factors [AOTA 2002]. This chapter discusses areas of assessment in the categories of areas of occupation, client factors, performance skills, and context.

Areas of Occupation

Clinical observation of the child participating in his or her occupations, and/or an occupation-based assessment, is necessary to determine the overall direction of the intervention program—and more specifically whether and how a splint will contribute to that intervention program. Each child and family attaches meaning to different occupations, and it is participation in these valued occupations that ultimately determines the success of the intervention program.

When considering a splint, it is essential that the therapist consider the child’s strengths and level of participation as well as musculoskeletal problems. Although the child may use an “abnormal pattern,” this pattern may afford the child his or her only opportunity for participation in valued occupations. It may be necessary for a temporary loss of function in the short term in order to gain increased function in the long term. However, careful thought should be given to splinting choices before deciding on an option that will take away a child’s ability to function in favor of “fixing” the problem. As Armstrong [2005, p. 481] stated, “Is an important action being taken away to gain something else? Which is more important?”

The decision about whether to splint, and what type of splint should be made, should be client centered—and the assessments used to determine the effectiveness of the splint should also be client centered [McKee 2004]. According to McKee, “An occupation-based approach ensures that the central therapeutic aim for splinting remains that of enabling either current or future occupation rather than the mere provision of a splint” [McKee 2004, p. 307].

Client Factors

The quality and distribution of muscle tone should be assessed at rest and during functional activity. The therapist should also determine whether the amount of tone varies according to the child’s mood, physical health, amount of effort exerted, or state of alertness. Some children have greatly increased tone during active movement but minimally increased tone during rest or while asleep. If the child’s muscle tone is not significantly increased at night, there may be no need for a night splint [Exner 2005]. Children with decreased tone may need a splint to stabilize or support joints. Children who are severely hypotonic and lack active movement may need splints to offset the constant pull of gravity that could lead to contractures.

Range of Motion

The therapist should measure both active and passive ROM and compare measurements with those taken previously to determine whether range is increasing, decreasing, or remaining the same. Before moving the joint, the therapist must be sure that the child is well positioned and is as relaxed as possible. The therapist should look for compensatory patterns the child may use to fixate or stabilize specific joints, because this will affect available joint range.

It may also be helpful to prepare the child’s musculoskeletal system for movement before taking measurements. Because muscle tone and sometimes cooperation vary, it may be necessary to take measurements on several occasions to get the most accurate estimate. Goniometric measurements are more reliable when taken by the same therapist. Even so, measurement error can occur. The therapist should describe the child’s position and the position of adjacent joints when measuring ROM to increase the likelihood that subsequent measurements are taken in the same manner.

Contractures

The therapist should discriminate between types of joint end feel. When tightness at a joint is primarily the result of muscle and soft-tissue shortening, with full passive range still possible with effort, this effect is known as soft end feel. When the joint cannot be moved to the end of passive range, it is said to have a hard end feel. The latter, where full passive range cannot be obtained, is known as a contracture [Hogan and Uditsky 1998, Yamamoto 1993].

A limb with a contracture is also said to have a deformity. One has only to tour a program, school, institution, or group home for individuals with developmental disabilities (especially those with more severe disabilities) to see multiple cases of contractures that restrict functional use of the upper extremities and that make caring (i.e., dressing, toileting, seating, bathing, and feeding) for these children and adults difficult. Never underestimate the deforming forces of spasticity, or lack of active movement, especially during the formative period of childhood growth and development.

Active orthotic management or splinting during childhood may prevent many contractures and resulting deformities and thus improve the quality of life for children and their families. Early orthotic intervention is usually less costly to the medical and educational systems than attempts to treat a deformity after the fact. Prolonged stretching of soft tissue (such as that provided with a splint) appears to be of greater benefit in reducing contractures than repeated briefer stretch typical of passive ROM exercises [Hogan and Uditsky 1998, McClure et al. 1994]. Provision of some passive ROM is still necessary to keep the splinted joints mobile. Passive ranging is also important for joints that are not splinted.

Understanding the possible physiologic mechanisms for the formation of a contracture can assist the therapist in splint design and establishment of wearing schedules. Hogan and Uditsky [1998], McClure et al. [1994], and Watanabe [2004] provided useful discussions of this topic. Briefly, when a joint is held in a fixed position (for example, wrist flexion) the result “is a decrease in the functional length of the periarticular connective tissues and associated muscles that have been held in this shortened position.…The muscle then accommodates to this shortened immobilized position through biological changes that take place such as a loss in the number of sarcomeres” [Hogan and Uditsky 1998, p. 71].

Preventing contractures, or minimizing their severity, is one of the most important functions of splinting for children with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies. Even with ongoing intervention, prevention of all contractures in children who have severely increased tone can be difficult and may not be possible. However, even if an existing contracture cannot be improved splinting should be done to prevent the contracture from becoming worse. A moderate contracture is better than a severe contracture because the latter can result in problems with skin breakdown and can make care much more difficult. When working to decrease a contracture it is important to keep in mind that “soft tissue connective tissue responds better to low-load prolonged stress (LLPS) than high-load brief stress (HLBS)” [Granhaug 2006, p. 419].

Integrity of Skin, Bones, and Circulatory System

In severe cases, the therapist should use extreme caution when splinting a child with osteoporosis because stress to the bones could cause a fracture. Osteoporosis in children occurs as a result of lack of weight bearing while bones are growing. Children with tightly fisted hands are at risk of developing maceration or skin breakdown in the palms or between the fingers, and maintenance of skin hygiene becomes a priority.

Some children experience pain in certain positions or have very sensitive skin. Other children have poor circulation, which necessitates careful monitoring of the color and temperature of the skin during splint wear. Finally, some children who have developmental disabilities also have significant feeding problems and may be underweight. Children with little subcutaneous fat probably have more difficulty tolerating pressure on bony areas, thus affecting the splint’s design and wearing schedule.

Performance Skills

The therapist should evaluate components of reach, grasp, manipulation, release, bilateral hand use, and tactile and proprioceptive reactivity and discrimination. It is important to evaluate upper extremity function in various positions, such as supported sitting, unsupported sitting, and prone, supine, and side lying. This gives crucial information about the proximal stability needed for effective distal function of the hand. Sensory system modulation should be observed. Hyperreactivity or hyporeactivity to sensory stimuli affects how the therapist approaches the child and influences splint selection and fabrication.

The child’s level of cognitive ability also affects hand use, and the therapist should obtain information about the child’s cognitive level. Because one of the most important determinants of a successful splint is the improvement of hand function, the therapist should use an objective measure of hand function such as a criterion-referenced assessment tool. This allows the therapist to periodically reevaluate and compare the child’s performance over time. A qualitative description of how the child moves and performs should also be included to complete the functional assessment.

Context

Children with disabilities live, rest, play, and are productive in a variety of environments—including home, school, child care centers, and sometimes hospitals. The fabrication and monitoring of splints may occur in any of these environments. When selecting and designing a splint, persons who are responsible for donning the splint must be considered. Simplicity of design is desirable and may be a necessity in cases where the child interacts with multiple care providers in a variety of environments. Compliance with using the splint is likely to decline as the complexity with the donning and wearing schedule increases. In the hospital setting, care must be taken to obtain information from family members and the treating therapist (if applicable) about home and school settings that will influence splinting decisions.

Careful planning must be made when splinting in the intensive care units of the hospital because splints must be fabricated with minimal handling of the infant or child and while navigating carefully around life-supporting tubes and monitors. Consideration must be given to incorporation of the use of the splints in the daily medical care provided by nursing staff. The therapist must also be familiar with the child’s medical condition and be able to recognize signs of stress that can be harmful to the child. Practice in the neonatal intensive care unit requires advanced competencies, and therapists considering practice in this environment should obtain training beyond entry level [Hunter 2005].

When a splint is used in the school environment, it must contribute to the child’s ability to benefit from a specially designed program of instruction such as special education. It is important for a child to be able to reach, grasp, manipulate, and release learning materials and other objects in order to function in the classroom, lunchroom, playground, hallways, library, and gymnasium.

The therapist should include the purpose of a splint as a part of educationally related occupational therapy described by the individualized education plan (IEP) if the child is 3 to 21 years of age or the individualized family service plan (IFSP) if the child is under 3 years of age. Remember, the splint is a means to an end and not the end itself. Therefore, the IEP or IFSP goal would be a measurable statement describing the child’s performance skills, patterns, or client factors and not the fabrication of the splint. The splint is part of the intervention that allows or facilitates participation in educational programming. This distinction is important if personnel at the school question whether splinting is an educational or a medical intervention.

Information about the home environment should be obtained from interviews with the parents and caretakers, and if possible via a home visit. Splints with wearing schedules incompatible with family schedules or splints that family members do not understand will not be used effectively. The family should not be expected to follow a “one size fits all” splinting protocol. Rather, the therapist must individualize the splint design and wearing schedule not only to fit the child’s needs but to fit the family’s strengths and needs. The therapist should always bear in mind that families are expected to carry out other therapeutic, educational, or medical interventions in addition to meeting the challenges of day-to-day life with a child who has a disability.

After an assessment is completed, the therapist can establish therapeutic goals and intervention strategies for the child. A splint may be a component of this treatment plan. According to Schoen and Anderson, orthotic devices (like adaptive equipment) are an important part of intervention because they reinforce neurodevelopmental treatment therapeutic goals: “If preventative measures such as adaptive equipment and orthotic devices are provided, then the child will receive consistent input to prevent or reduce the occurrence of deformities and limitations” [Schoen and Anderson 1999, p. 107]. Once a decision is made to provide a splint for a child, the splinting process is initiated.

Overview of the Splinting Process

Position the child so that the effects of abnormal tone and postural reflexes on the arm and hand are at a minimum. This position depends on the results of the assessment of the individual child and may be different from how the child is typically positioned. It is important to provide external stability through equipment or handling for children who have not acquired internal stability of proximal joints. This may involve a seating system or other adaptive equipment. For the infant or young child, it may be possible for the parent to hold the child and provide external stability with the therapist’s instructions.

It is also important to reduce the child’s fearfulness and maximize his or her cooperation. If the therapist does not already have a relationship with the child, time must be provided to allow the child to warm up to a stranger. Even if the child knows the therapist, a brief time should be provided to allow the child to acclimate to the equipment and setup for splinting. The therapist should have toys, music, books, stickers, or other materials to establish a reciprocal interaction with the child before starting the fabrication process. With an infant, the therapist can talk in a soothing voice and touch the child in a playful manner before fabrication. With an older child, the therapist can show the child what to expect by first fabricating a “splint” on a doll or stuffed animal or by making “thermoplastic jewelry” or other play objects.

When appropriate, the child should be given the opportunity to touch and feel the material while it is warm and soft and again after it becomes cool and hard. The child’s response to tactile stimuli should be noted, and if signs of tactile defensiveness occur the therapist should follow sensory processing guidelines for improving sensory system modulation. If colored thermoplastic material is available, the child should be encouraged to select a color. Decorating the splint with stickers or leather stamps also encourages the acceptance of the splint for some children.

Giving children a role to play in the fabrication process may increase their cooperation. This could include keeping time by counting, holding the tail of the Ace wrap, or any other role the therapist can invent to keep them involved. However, if associated reactions are present it is best for the child to be involved without exerting effort—because this may increase tone. Although preparing the child may take a few extra minutes at the beginning of a splinting session, it can save hours of frustration in having to reschedule or remake a splint because of lack of cooperation.

Prepare the Environment

Thoughtful preparation is especially important when splinting children because of their short attention spans. In addition to having splinting and play materials close at hand, it is recommended that the therapist plan to have a second pair of adult hands to help with the fabrication process [Armstrong 2005]. This additional person might be a parent, teacher, paraprofessional, or another therapist. This is especially important if the child has increased tone, is not able to follow verbal instructions, or is likely to be uncooperative. The therapist must clearly explain the helper’s role so that efforts assist the process and not hinder it. This usually involves maintaining the child’s overall position, calming or entertaining the child, holding the arm just proximal to the joint being splinted, or stabilizing the material once in place and while it is cooling.

Selection of Splinting Materials

Pediatric splints may be made of many different types of materials, depending on the purpose of the splint and the age and needs of the child. Thermoplastic materials are commonly used for the fabrication of static splints or those that require restricting motion at certain joints. Soft splints are commonly made of materials such as neoprene. Soft splints may not totally immobilize a joint, but they provide support and allow greater freedom of movement. Children with athetosis or involuntary flailing movements should be protected from possible harm from the splint by selection of a soft material or by covering a thermoplastic material with a mitt or sock.

When splinting with neoprene, the therapist should be alert to the possibility of skin irritation or rash. According to Stern et al. [1998, p. 573], “skin contact with neoprene poses two dermatological risks: allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) and miliaria rubra (i.e., prickly heat).” Although neoprene hypersensitivity is rare, the authors recommend that therapists screen patients for a history of dermatologic reactions; instruct clients to discontinue use and inform the therapist if a rash, itching, or skin eruptions occur; and report cases of adverse skin reactions to the manufacturer of the neoprene material. They also recommend that therapists limit their own exposure to neoprene and neoprene glue because of the exposure to thiourea compounds that are thought to contribute to allergic reactions.

Thermoplastic materials range in conformability (and in stretch, thickness, and rigidity) and are described in Chapter 3. Generally, thermoplastic materials with a high plastic content have more conformability—whereas materials with a high rubber content have less stretch but are less likely to be indented with fingerprints during fabrication or stretch out of shape. When making a splint that counteracts the forces of spasticity, it is especially important to select a thermoplastic material that resists stretch (i.e., one with a high rubber content) because it is necessary for the therapist to apply considerable pressure to obtain the desired position of the wrist, thumb, and fingers [Armstrong 2005].

There are also products that combine the properties of plastic and rubber. Usually the rubberlike (or combination) thermoplastic material is necessary when one is splinting against spasticity, even though it is less rigid than the plastic type. If necessary, a reinforcement component can be added to the splint. Selecting a material with a high degree of memory is helpful when one is working with a child whose movements may be unpredictable and require the therapist to start over (sometimes more than once!). These plastics are elastic-like and self-adhere easily. This latter characteristic can also be problematic.

One way to reduce the stickiness is to add a tablespoon of liquid soap or shampoo to the hot water [Hogan and Uditsky 1998]. When splinting a neonate or young infant, the standard  -inch material may be too thick and heavy. Rather, the therapist should use material that is 1/16-inch or 3/32-inch in thickness. The therapist’s experience and preferences also affect the choice of thermoplastic material. (See Chapter 3 for a review of splinting material.)

-inch material may be too thick and heavy. Rather, the therapist should use material that is 1/16-inch or 3/32-inch in thickness. The therapist’s experience and preferences also affect the choice of thermoplastic material. (See Chapter 3 for a review of splinting material.)

Patterns

Patterns are made for each splint on each child, depending on the therapeutic goal of the splint and the child’s characteristics. A pattern is essential. It not only determines the correct size and fit but allows the therapist to conceptualize the entire splinting process. The pattern can be revised through trial and error until the desired result is achieved. Patterns can be made from paper, such as paper towels, or from aluminum foil. Masking tape can be used to repair tears or reinforce contours. Many children with abnormal tone may be unable to lay their hands on a table surface for tracing. In this case, the pattern must be held under the extremity in whatever position is least stressful. The therapist may also consider using an uninvolved contralateral side to start a pattern, given there is some symmetry of anatomy.

It may be helpful to plan on extending the splint material a little beyond that of the finished product in order to give the therapist leverage to help hold joints in position. The extra can be cut away when the essential part of the splint is finished and hardened [Granhaug 2006].

Heating the Thermoplastic Material

The therapist should heat the water to the temperature range recommended by the manufacturer. After cutting out the splint, it may be necessary to reheat the plastic to obtain the desired degree of pliability before the molding process. Before placing the plastic on a child’s extremity, the therapist should dry off the hot water and make sure the plastic is not too hot. Checking the thermoplastic material’s temperature can be done by placing it against the therapist’s face or anterior portion of the forearm. This is especially important when spot heating with a heat gun because this method tends to result in higher surface temperatures.

Some children may be hyperreactive to temperature and react negatively, even though the temperature does not feel hot to the therapist. Because many children cannot communicate that the plastic feels too hot, the therapist should watch the child’s facial expressions and listen for vocalizations that indicate discomfort. The child’s arm and hand can be moistened with cold water just before molding, or the therapist can wait longer for the plastic to cool. Some therapists use stockinette to protect the extremity. However, care must be taken that it does not wrinkle under the plastic during fabrication.

Hastening the Splinting Process

Time is of the essence when one is splinting a moving target, a rebellious little one, or a difficult-to-position extremity. Rubber-based plastics, which are necessary to resist stretch, are somewhat slower to harden. Once the plastic is in place on the extremity, an ice pack can be rubbed on the splint to hasten the setting process. A rubber glove filled with ice chips can easily serve the purpose. After partially hardened, the splint can be carefully removed and put into a pan of ice water or placed under a faucet of cold running water to finish hardening.

A spray coolant may be used, but only with great care to spray after the splint is off the child and with the spray directed away from the child. The use of coolant spray should be avoided with children who are unable to keep their heads turned away from the direction of the spray and those who have frequent respiratory problems.

A Theraband roll that has been cooled in a freezer can help form the splint, especially for the forearm. This will accelerate the cooling process at the same time. If not available, an Ace wrap can be useful to hold the forearm trough in place while the therapist works on the hand portion of the splint—although this maintains heat and may increase setting time. In either case, the therapist should not apply the wrap or Theraband too tightly and should flare the edges of the forearm trough away from the skin after formation of the splint.

Padding

Padding, or some form of pressure relief, may be necessary over bony areas to prevent skin problems. Padding does not compensate for pressure resulting from a poorly made splint. Padding takes up space, a factor the therapist must take into account before formation of the splint. Otherwise, the amount of pressure against the skin may increase. A variety of paddings exist, including closed- and open-cell foam and gel products. Pressure-relief padding with a gel center is useful in protecting bony areas for children with little subcutaneous fat.

To ensure a proper fit, the therapist should lay the padding on the child’s extremity before molding the plastic or place it on the thermoplastic material before molding the splint. When molding with padding, the stretch of the thermoplastic material and the contourability may be compromised. Therefore, the therapist should add padding only if absolutely necessary. In addition, padding becomes soiled and needs to be replaced. For more information on padding, see Chapter 3.

Another way to create pressure relief around a bony prominence without using padding is to cover the prominence with a small amount of a firm therapy putty before forming the splint. The putty creates a built-in bubble and is removed from the splint after cooling [Hogan and Uditsky 1998]. Thin forms of padding may also be useful to create friction and reduce migration or shifting of splints, or for covering edges. Microfoam tape is useful for this purpose, especially on small splints.

Strapping

A variety of strap materials are available. The therapist should consider strength, durability, elasticity, and texture when the strap is against the skin. Strapping with sharp edges should be avoided with younger children and those with sensitive skin. The wider the strap the more force is dispersed, as long as the entire strap width is in full contact with the skin. Strap material may have to be cut narrower, especially around the wrist and fingers, to be proportionate to the size of the child’s hand.

Straps can be secured at each end with hook Velcro, which is attached to the splint. This allows them to be easily replaced when they become soiled, which is important if the child drools on the splint or mouths it. However, loose straps easily become lost and many times are not placed on the splint at the correct angle or location. An alternative is to adhere the strap at one end with a rivet or strong contact adhesive. When soiled, straps must be removed by the therapist and a new strap reattached. See Chapter 3 for more detailed information about attaching straps.

Increasing the likelihood that the child will not remove straps and the splint requires knowledge of child development and creativity. Children at certain ages (such as 2- and 3-year-olds) are in the developmental stage of asserting their autonomy and may resist the parent’s choice of clothing or food or splint application. In this case, using principles of behavior analysis (such as shaping or rewarding successive approximations, finding times during the day when the child is most likely to be compliant, and contingent use of praise and attention) may be helpful. Actively involving the child in the choice of colors and decorations may increase the child’s willingness to wear the splint. Strap Critter patterns are provided by Armstrong [2005], along with suggestions for using decorative ribbon, fabric paints, or shoelace charms. She also suggested describing the splint as something cool to wear and providing the child with language to use to explain to peers, such as this is my Batman or scuba diver’s glove.

If positive methods to prevent splint removal have not worked, therapists can use their creativity to keep the little “Houdinis” in their splints, especially young children who do not understand cause and effect. Some kid-proof methods include using shoelaces, buttons, or socks/stockinette/puppets. Lacing can be done by punching holes along the lateral edges of the splint and lacing with wide decorative shoelaces. The therapist should place padding under the laces against the skin. To secure the laces, the therapist can use a “bow biter” (a plastic device available in children’s shoe departments) to hold the laces in place [Collins 1996]. Depending on the function of the splint, a sock puppet worn over the splint may be used as camouflage (Figure 16-1). Care must be taken not to provide any attachment the child could bite off and swallow.

Providing Instruction for Splint Application

Those responsible for applying the child’s splint should have been part of the assessment process and should have already provided input on the splint design and have agreed with the need for the splint. They must understand the splint’s purpose, the rationale for using the splint, precautions, and risks of incorrect usage. Although the correct application of the splint may seem obvious to the therapist, it may not be obvious to many teachers, nursing staff, or parents unfamiliar with splints.

The more complex the splint the more detailed and explicit the instructions should be. This is especially true when there are multiple care providers. The therapist should provide written instructions, along with a phone number and/or e-mail to contact with questions or concerns. A demonstration of the steps involved in putting the splint on correctly should be provided, followed by an opportunity for the caretaker to practice applying the splint under supervision. A photograph of the child’s forearm and hand, showing the splint on the child in the correct position, is often an effective teaching tool if it does not conflict with policies regarding confidentiality.

Correct placement of straps can be facilitated by writing a number or placing a small design on the strap end and a corresponding number or design on the splint. The therapist should do everything possible to take the guesswork out of putting on the splint. It is also wise to instruct the caregivers to inspect the skin every time the splint is removed to assess the splint for signs of excessive pressure.

Wearing Schedules

Wearing schedules vary according to the purpose of the splint, the child’s tolerance for the splint, the child’s musculoskeletal status, and the child’s occupations and daily routines. Splints may be worn for long or short intervals during the day, at night, during functional activities, or a combination of these. It is necessary to gradually increase the wearing time initially to build up the child’s tolerance for the splint and to make any modifications that become apparent with use.

When the purpose of the splint is to increase functional use of the hands, wearing the splint should occur during times when the child is engaged in occupations. If the purpose is tone reduction, the splint should be worn just prior to activities or occupations. When the purpose of the splint is to prevent a contracture, the splint should be worn when the child is not engaged in occupations. Finally, if the splint is used to treat an existing contracture it is necessary for it to be worn for prolonged periods of time.

The total time spent wearing the splint during a 24-hour period appears to be more important than whether it is worn continuously or intermittently [Hogan and Uditsky 1998]. The length of time a splint can be worn is also affected by how much force is being applied to achieve the splinted position, which causes stress on the joints, muscles, and skin. Ultimately, wearing schedule decisions are based on developing and maintaining clinical competence, clinical reasoning, and collaborating with the child and/or family members or care providers.

The wearing schedule will work only if the splint is placed on the child during the times recommended. Incorporating the splint schedule into the child’s regular routine may increase compliance because it becomes less of a special chore for the parent, teacher, caregiver, or nursing staff. The therapist should document the agreed-upon wearing schedule (along with instructions for putting on the splint) and provide written copies to parents, caregivers, teachers, nurses, and child care providers. As the child’s developmental or ROM status changes, the therapist must evaluate the wearing schedule and possibly the splint design to make necessary modifications.

Precautions

The skin should be inspected frequently during the initial wearing phase. A distinct red area or generalized redness that does not disappear within 15 to 20 minutes after splint removal indicates excessive pressure and the need for revisions [Hill 1988, Hogan and Uditsky 1998]. During periods of monitoring, the therapist should be aware of any problems associated with joint compression, pressure on nerves, compromised circulation, and dermatologic reactions. Children’s growth spurts often come without obvious signals and during times of growth therapists and caregivers should be extra vigilant.

Evaluation of the Splint

A plan should be made for the therapist to reassess the splint on a regular basis to ensure proper fit and function. The therapist should consider having the care provider put the splint on an hour before the reassessment. This allows the therapist to observe how the splint is put on and whether the splint migrates out of position after initial donning. A poorly fitting splint can do more harm than good.

This overview applies to all pediatric splints. The following section provides information specific to several common splint designs used with children who have a developmental disability or congenital anomaly.

Resting Hand Splint

The purpose of a resting hand splint is to prevent a contracture or deformity, to prevent an existing deformity from becoming worse, or to gradually improve or reduce a deformity (deformity-reduction splint). Children who are at the greatest risk of developing a contracture are those with moderately to severely increased tone or those with severely decreased tone who have no active movement. For children with severely increased muscle tone and tightly fisted hands, an additional purpose may be maintenance of skin hygiene.

Features

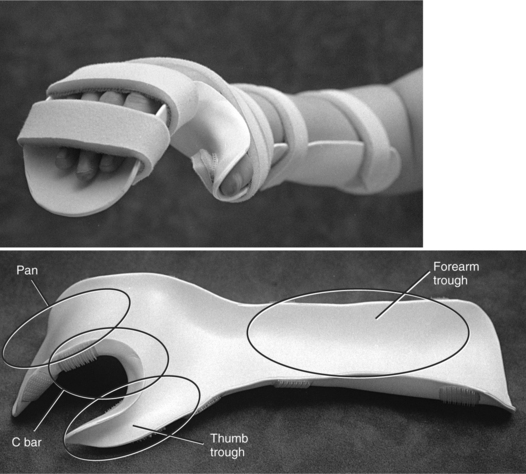

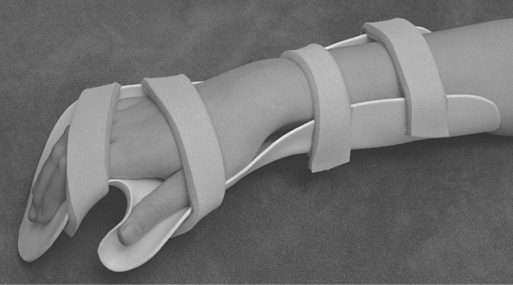

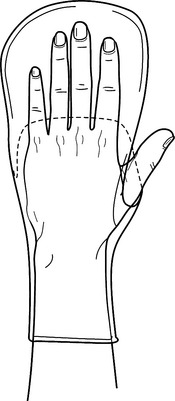

The components of a resting hand splint for a child are the same as those described in Chapter 9, except for the shape of the thumb trough and C bar. Components include a forearm trough, a pan for the fingers, a thumb trough, and a C bar (Figure 16-2). If spasticity is present in the thenar muscles, the thumb should be positioned in partial radial abduction in order to elongate the opponens muscle. Sustained stretch of tight thenar muscles may also inhibit tone in the hand [McKie 1998].

For children with moderately to severely increased tone, the ideal position of the wrist, fingers, and thumb may not be possible. Because its purpose is to prevent or reduce joint deformity, the splint should provide as much elongation of the tight muscles as possible without causing excessive stress. The child should also be able to tolerate wearing the splint for several hours at a time to obtain the maximum benefit.

If the splint places the hand into the maximum range of passive motion, the forces generated may compromise circulation, cause skin breakdown, elicit pain, or reduce the length of time the child can tolerate wearing the splint. Therefore, the splint should place the wrist joint in submaximum range [Exner 2005, Hill 1988]—a position especially important at the wrist to allow for extension of the fingers. Low-load prolonged stretch provided by casts or splints is the best conservative way of increasing passive ROM [Duff and Charles 2004]. When flexor spasticity is severe, serial splinting may be necessary [Duff and Charles 2004, Exner 2005].

The therapist can usually determine the best splinting position by handling the child’s extremity and feeling the amount of passive resistance. After achieving the desired position manually, the therapist should note the angles of the joints involved and where pressure is being applied to obtain this position. Handling the joints and feeling the resistance from muscles helps the therapist determine the most therapeutic position and the location of force application during splint fabrication and strap application.

Process to Fabricate a Resting Hand Splint

Thermoplastic Material Selection

When making a splint that counteracts the forces of spasticity, the therapist should select a low-temperature thermoplastic that resists stretch. A considerable amount of pressure is applied against the splinting material while the therapist obtains the desired position of the wrist, thumb, and fingers. This pressure can indent and inadvertently stretch materials that have conformability. Usually a thermoplastic material containing a higher rubber content will have the desired working characteristics. (See “Overview of the Splinting Process.”)

Pattern

The pattern should include the measurements and markings of landmarks (see Chapter 9). Because the thumb position of this splint is different from the traditional resting hand splint, the thumb trough and C bar are shaped differently (Figure 16-3). After the pattern is drawn and cut out, the therapist fits it to the child and makes further modifications as necessary. While making the pattern and molding the splint, the therapist should position the child to minimize the effects of abnormal tone and postural reflexes on the body and the extremities.

Padding

Before forming the splint, the therapist should consider the need for padding to allow the additional space necessary. Because padding places some restrictions on forming the splint and keeping it clean, it should not be used unless the assessment shows the child to be at risk of skin problems. Creating bubbled-out areas over bony areas may be sufficient to avoid skin problems. If used, follow guidelines described in the section headed “Overview of the Splinting Process.”

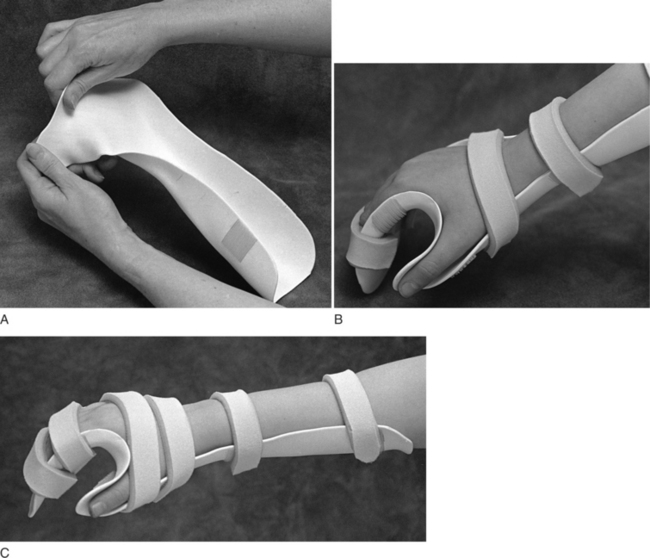

Forming the Splint

Before placing the plastic on the child’s extremity, the therapist should prestretch the edge of the splint that forms the C bar (Figure 16-4A). The therapist should then place the soft plastic on the child’s upper extremity so that it conforms to the web space of the thumb (Figure 16-4B). If available, an assistant stands beside the child and secures the forearm trough. The therapist should form the splint into the palmar arches and around the wrist and thumb. To obtain the desired contour and fit, the therapist may need to be aggressive when molding into the palm and around the thenar eminence—especially if working against spasticity.

Figure 16-4 (A) Prestretching of the C bar. (B) The fit of the C bar into the web space. (C) The contour of the C bar.

The therapist must form the splint so that the bulk of pressure positioning the thumb is directed below the thumb metacarpal phalangeal (MP) joint and distributed along the thenar eminence. This formation is necessary to avoid hyperextension and possibly dislocation of the thumb MP joint [Exner 2005]. The thumb trough should cradle the thumb and extend about ½inch beyond the end of the thumb. The interphalangeal (IP) joint of the thumb should be slightly flexed, and the C bar should fit snugly into the web space and contour against the radial side of the index finger (Figure 16-4C).

Forearm Trough

After completing the wrist, palm, and thumb portion, the therapist can finish forming the forearm trough. (See Chapter 9 for guidelines on securing the forearm in the trough and avoiding pressure points.) If the edges of the trough are too high, the straps will bridge (i.e., the straps are raised from the skin’s surface and do not follow the contour of the forearm, thus losing skin surface contact). To keep the forearm securely in place, the straps should have maximum surface contact. If not secure, the forearm may rotate in the trough or the splint may shift distally and the position of the wrist, fingers, and thumb will be compromised.

Pan

Finally, the therapist forms the finger pan to position the fingers. The pan may require reheating because controlling all joints at the same time is often difficult. (See Chapter 9 for the correct width and height of the pan.) In addition, the distal portion of the pan should extend about ½ inch beyond the fingertips to allow for growth. When forming the curve of the pan, the therapist should follow the proximal and distal transverse arches.

Straps

The correct placement of straps is as important as correct formation of the splint, especially when the splint is holding against increased muscle tone. The straps and splint must work together to create the necessary leverage and to distribute pressure. If the forearm, palm, fingers, and thumb do not stay in the correct position in the splint, the benefit of the splint is greatly reduced. The optimum location and angle of each strap should be determined in relation to the forces being applied by abnormal muscle tone.

The forearm trough requires two straps for an older child. However, for a smaller child or an infant one wide strap across the forearm may be sufficient. Stability should be provided at the proximal and distal areas of the forearm. If considerable wrist flexion is present, two straps will be necessary to provide three points of pressure to secure the wrist.

One strap should extend directly across the wrist just distal to the ulnar styloid, and a second strap should be angled from the thumb web space across the dorsum of the hand and secured proximal to the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints on the ulnar side. Otherwise, one strap across the dorsum of the hand may be sufficient. If there is considerable finger flexion, straps may be needed across each of the three phalanges. Finally, the therapist should add a strap between the MP and IP joints of the thumb. When making a small splint for a young child, the therapist should make the straps narrower. (SeeFigure 16-5 for an illustration of strap placements, although not all of these may be necessary on every splint.)

Adaptations

The resting hand splint provides a basic form for positioning the child in good alignment and may serve as an inhibitor of hypertonicity. However, often the therapist must deviate from the basic form to truly meet the needs of the child. One way the splint can be adapted is by the addition of finger separators (also described in Chapter 9) to abduct the fingers and assist in tone reduction. This can be done by bubbling the material between digits or by simply attaching a roll of thermoplastic material between the digits. Finger separators can also be made from thermoplastic pellets or elastomer.

With pellets, the therapist softens them in hot water and kneads them together to the shape and size required. The pellets have 100% memory and are attached in the same way as any other thermoplastic material. Because of the puttylike consistency, these pellets work well when the therapist needs to make individualized finger separators—such as for children who have arthrogryposis and different deformities in each finger [Hogan and Uditsky 1998].

Elastomer is a silicone-based putty that can be used in pediatric splinting for thumb positioning or finger spacers. Pellets and elastomers are available from many splinting product catalogs. The putty types of elastomers “with a gel catalyst or the 50/50 mix are probably the easiest to work with because they can be mixed in the hand and varied in stiffness by adding more or less catalyst” [Armstrong 2005, p. 485]. Another option for modeling is Permagum, a silicone rubber dental-impression material [Bell and Graham 1995]. Elastomers and pellets may also be used to maintain the palmer arches or as a base for a small hand splint [Granhaug 2006].

The therapist may choose to use a dorsal-based resting splint [Armstrong 2005, Snook 1979] as an alternative to the palmar-based splint already described. This design is illustrated in Chapter 9. The dorsal-based splint will avoid sensory input to the forearm flexors, although it is somewhat more difficult to fabricate. For a child with very tight wrist flexors, donning the dorsal-based resting splint may be easier than the palmar-based splint. The child’s fingers can be placed into the finger slot (with the fingers sufficiently through the slot to support the MP joints), pressure can be placed across the wrist flexors, and slowly the forearm trough can be levered down onto the dorsum of the forearm. Armstrong [2005] is a good source of information on fabricating this splint for children.

Infants with congenital finger contractures often need resting hand splints. However, when all digits are not affected the splint may be altered to free nonaffected digits to engage in movement and sensory experiences. Resting hand splints may be made with alternative materials, especially for infants. The therapist may select a semirigid pliable material when splinting neonates, as it is less likely to cause abrasions. Bell and Graham [1995] describe the use of Permagum, a silicone rubber dental impression material, to mold into shape for neonatal splints. Several layers of adhesive cloth tape may also be an effective semirigid support.

Precautions

When splinting against increased muscle tone, the therapist must consider biomechanical principles of force distribution. The therapist should monitor for any undesired lateral forces on the fingers or wrist that may result in poor anatomic alignment or dislocation or deformity. In addition, the therapist should be aware of any circulation compromise or pressure on nerves. The therapist must make astute observations and elicit important information from the child, parent, or caregiver—especially when assessing very young children or those with communication dysfunction.

Precautions for this splint are the same as those for any splint. (See Chapter 6 for guidance in determining problems with skin, bone, or muscles.) When applying these precautions to a child who has increased tone, the therapist should shorten the initial wearing time to 15- to 20-minute intervals on the first day. The therapist should then carefully inspect the skin. A distinct red area or generalized redness on the skin that does not disappear within 15 to 20 minutes after splint removal indicates excessive pressure and the need for revisions [Hill 1988, Hogan and Uditsky 1998]. If no pressure areas are present, the therapist may increase the wearing time to 30-minute intervals. The therapist may then increase the wearing time by adding 15 to 30 minutes of wearing time until the maximum wearing period for the child is reached.

An additional precaution to consider when making a resting hand splint for a child who has moderately to severely increased tone is maintaining the integrity of the MP joint of the thumb. The therapist must direct pressure below the MP joint of the thumb. Exner [2005] cautions that distal force to the spastic thumb can result in hyperextension and dislocation of the MP joint.

Wearing Schedule

The wearing schedule is determined on an individual basis, as are all other aspects of the treatment plan. In general, the more serious the threat of deformity the longer the splint is worn each 24 hours. If tone continues to be increased at night, this may be a good time for extended wearing unless it interferes with the child’s sleep or presses against another part of the child’s body. During the day, the splint is removed for periods of passive ranging, active movement, and opportunities for sensory experiences.

McClure et al. [1994] provide a flow chart or algorithm for making clinical decisions regarding wearing schedules for splints. They describe the biologic basis for limitations in joint ROM and increasing ROM. This information is especially helpful in cases in which contractures already exist. According to these authors, “the primary basis for using splints to increase ROM is that by holding the joint at or near its end-range over time, therapeutic tensile stress is applied to the restricted periarticular connective tissues (PCTs) and muscles. This tensile stress induces remodeling of these tissues to a new, longer length, which allows increased ROM” [McClure et al. 1994, p. 1103]. McClure et al. [1994, p. 1102] define remodeling as “a biological phenomenon that occurs over long periods of time rather than a mechanically induced change that occurs within minutes.”

It is also beneficial for the child to participate in occupations immediately after removal of the resting hand splint to capitalize on increased hand expansion and elongation of tight muscles. If developing or improving functional hand skills is a primary goal, the splint should be removed more frequently or for longer periods of time.

Providing Instruction for Splint Application

It is imperative that those individuals responsible for applying the child’s splint know how to do so correctly. In addition, caregivers should understand the purpose of the splint, precautions, risks of incorrect usage, and how to reach the therapist with questions or concerns. See “Overview of the Splinting Process” for a description of instructing others in splint application and uses.

Evaluation of the Splint

The self-evaluation described in Chapter 9 can be used to evaluate the finished splint. In addition to evaluating the splint after fabrication, the fit of the splint should be reviewed at regular intervals. The splint’s effectiveness in accomplishing stated goals and outcomes should be reevaluated on an ongoing basis.

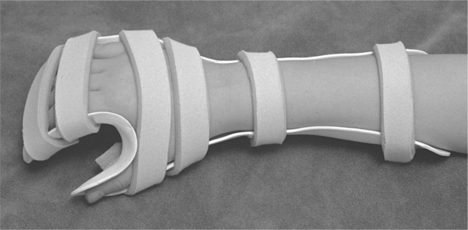

Weight-Bearing Splint

The weight-bearing splint (Figure 16-6) positions the hand in the most effective position for weight-bearing activities [Kinghorn and Roberts 1996, Lindholm 1986]. The splint requires significant wrist extension for effective use. The weight-bearing splint is used as a therapeutic tool, generally with children who have mild to moderate spasticity in their upper extremities. It is worn only during intervention. According to Lindholm [1986], the splint positions the wrist in extension to counteract the usual position of wrist flexion resulting from spasticity.

This position allows weight bearing through the heel of the hand. The splint positions the hand to allow normal weight bearing through the lateral borders of the hand and the fingertips. An effectively positioned hand allows the child to work on more proximal control. The splint serves as an assist for positioning the hand while the child is performing weight-bearing activities. During therapy, the splint allows the therapist to focus less on the hand and fingers and more on facilitation or inhibition techniques of the upper extremity.

Features

The weight-bearing splint was originally designed as a hand-based splint. However, more stability is provided when the splint is fabricated with a forearm trough. The weight-bearing splint is similar in design to the aforementioned resting hand splint. However, there is more extension at the wrist and the thumb is in more radial abduction.

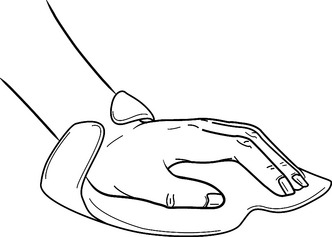

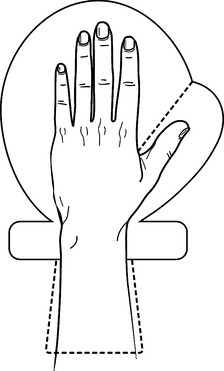

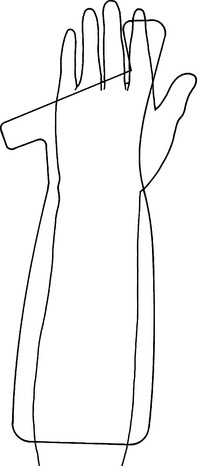

Pattern

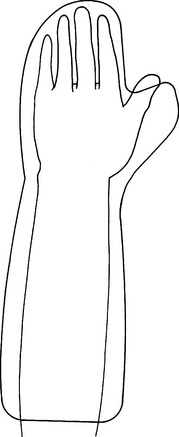

The pattern for the weight-bearing splint (Figure 16-7) is similar to that for the resting hand pattern. However, extra space is provided when tracing around the fingers and thumb. The web space is not tapered. The pattern should look like a mitt for the hand. If a forearm trough is added to the splint design, it should extend two-thirds the length and half the circumference of the forearm.

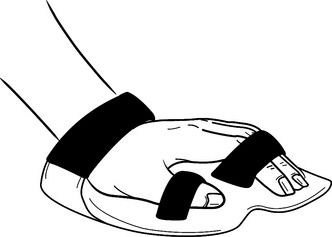

Forming the Weight-Bearing Splint

Mold the splint on the volar surface of the hand. The proximal interphalangeal joints and distal interphalangeal joints should be in slight flexion and the thumb in radial abduction (Figure 16-8). The wrist should be in 45 to 50 degrees of extension. Much attention should be given to the palmar arches by positioning the hand in a cupped position. A small ball that fits comfortably in the child’s hand can be used to reinforce the arches. A wide strap over the IPs will aid in keeping the fingers on the mitt. A diagonal strap over the wrist reinforces the wrist position. Straps should be placed proximally and distally on the forearm trough.

Precautions

This splint requires adequate wrist extension. ROM must be obtained before it is fabricated. When the wrist is in extension, the fingers often attempt to curl into flexion. Attention should be given to stabilizing the fingers in slight abduction.

Adaptations to the Weight-bearing Splint

To maintain stability of the fingers, slits may be made in the hand portion of the splint. This is accomplished by threading the strapping material through the slit and looping it over each joint (seeFigure 16-8). To ensure stability at the hand, a dorsal hood may be fabricated by draping thermoplastic material over the dorsum of the hand. If additional concerns exist with respect to stabilizing the wrist and dorsum of the hand, the wrist and the forearm may be covered with thermoplastic material. This will create a clam shell type of splint (Figure 16-9). Because considerable pressure may be present, the dorsal piece of the splint may require padding.

Wrist Splints

A therapist usually selects a wrist splint to improve functional use of the hand rather than to prevent or manage a deformity. Providing proximal stability at the wrist, the splint allows for improved control of distal finger movement for grasp and release. When a therapist uses a wrist splint for a child who has tightness of the long finger flexors, the splint may have to position the wrist in slight flexion. Otherwise, the child may be unable to actively extend the fingers—thus restricting participation in occupations.

Because of the tenodesis effect, the wrist splint may not be appropriate if the finger flexors have severe tightness causing a fisted hand posture. If the child has only mildly increased tone or is hypotonic, a soft wrist splint with a reinforcement component under the wrist may be preferable. If tightness is also present in the opponens muscle, a splint that includes a thumb trough may be indicated.

The thermoplastic wrist splint can be either volarly or dorsally based. The volar design is more effective if wrist flexion is difficult to control. However, it covers the palm of the hand—thus reducing sensory input and creating more bulk in the hand. The dorsal design allows more sensory input to the palm but may be more difficult to construct when the child has wrist and finger flexor spasticity. If the palmar bar is too narrow, it can be dangerous and painful. It is also more difficult to add attachments, such as a pointer, to the dorsal wrist splint. This chapter describes the process for the volar design. See Chapter 7 for a description of the dorsal design.

The wrist splint may be used alone or alternately with a resting hand splint. This combination would be appropriate for a child who has some functional use of the hand but is at risk of developing contractures.

Process to Fabricate a Volar Wrist Splint

The selection of tools and materials is essentially the same as that described previously for the resting hand splint. A thermoplastic material that resists stretch is frequently desirable when the therapist positions the wrist of a child with spasticity. However, when the purpose of a wrist splint is to serve as a base for attaching pointers or holders the thermoplastic material’s surface must be properly prepared for self-bonding. It is preferable to select a thermoplastic that has a high degree of self-adherence (see Chapter 3).

Pattern

After tracing the child’s extremity, the therapist makes the splint pattern. Use the guidelines presented in Chapter 7 to locate landmarks and determine how the splint should fit in the palm. (SeeFigure 16-10 for a sample pattern.)

Forming a Wrist Splint

The fabrication process is essentially the same as described in Chapter 7. The splint should follow the contour of the palmar arches as they are configured during grasp [Hill 1988]. The splint should not interfere with MCP flexion or thumb opposition. The therapist rolls the edges around the thenar eminence and MP bar. Occasionally, rolling an edge can cause the splint to become too bulky. Minimally, the edges should be contoured to prevent pressure areas from the edges. The ulnar side of the splint may require a bubble to accommodate the ulnar styloid.

Straps

The needs of the child determine the number and angles of straps. Usually two straps secure the forearm trough (although in some cases this can be accomplished with one wide strap) and one strap secures the hand. The hand strap is angled from the ulnar side of the metacarpal bar to the hypothenar bar. The therapist may have to cut the strap material narrower for small children.

Precautions

The precautions for the application of the wrist splint to children are essentially the same as those for the adult (see Chapter 7). The splint should distribute pressure to avoid skin irritation. In addition, the splint must stabilize the forearm so that the splint does not shift during use. The splint should not interfere with thumb opposition or MCP flexion of the fingers.

Wearing Schedule

The therapist should consider the child’s therapeutic goals, occupations, and the extent of functional hand skills with and without the splint. In general, the child wears the splint during activities that require grasp and release that can be accomplished more easily while wearing the splint.

Evaluation of the Splint

The therapist can use a self-evaluation form to determine whether the fabrication of the splint is correct (see Chapter 7). The therapist should also perform frequent, ongoing reevaluation of the splint’s effectiveness and the child’s functional hand skills.

Adaptations to the Splint

Adaptations to the wrist splint include the attachment of pointers, crayon holders, or other assistive devices (Figure 16-11). When designing a pointer, the therapist should angle it so that the pointer is within the child’s visual field. When possible, the therapist makes a finger trough to position the index finger for pointing—thus allowing sensory feedback to the tip of the index finger after contact is made with the target.

A spiral finger trough allows for more sensory input. Some children may benefit from the addition of a spiral strap to facilitate partial supination while wearing the wrist splint. This can be accomplished by attaching a strap to the palm of the hand and wrapping it radially across the dorsum of the hand over the wrist and forearm and attaching it to itself just proximal to the elbow.

Thumb Splints

Increased muscle tone frequently pulls the thumb into palmar adduction. The purpose of a thumb splint is to improve functional use of the hand by stabilizing the thumb in a functional position of opposition. The therapist uses this splint for a child who has some active wrist and finger extension but has difficulty actively moving the thumb out of the palm because of increased tone. If tone is moderate to severe, a splint made out of thermoplastic material may be more effective.

If tone is mild to moderate, a splint made from a more pliable material such as neoprene is recommended. Thumb splints can be hand or forearm based. This section describes hand-based thermoplastic splints and neoprene thumb splints that are hand and forearm based. Fortunately, prefabricated thumb splints for children have become much more common in recent years. They are discussed in the material following.

Thermoplastic Thumb Splint

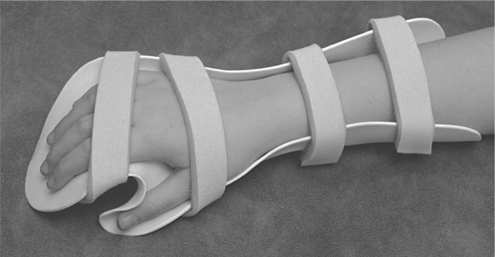

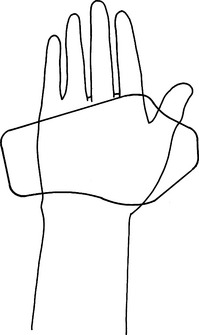

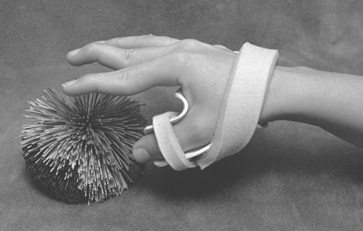

The hand-based thumb splint can be of a palmar or dorsal design. The dorsal design results in less bulk in the palm, but the splint may not apply adequate pressure against spastic thenar muscles and can be difficult to don. The palmar design includes a metacarpal bar, a thumb trough with a C bar, and a hypothenar bar (Figure 16-12).

Process to Fabricate a Thermoplastic Thumb Splint

The selection of tools and materials is essentially the same as previously described for the resting hand splint.

Forming the Splint

After cutting out the splint and reheating the material, the therapist places the material on the child’s hand and carefully molds the C bar to the thumb web space. The hypothenar bar wraps around the ulnar border of the hand far enough to secure the hand, and the metacarpal bar is rolled proximal to the distal creases to allow finger flexion. The body of the splint should conform to the palmar arches as they occur during grasp and should extend proximally far enough to adequately position the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb but not so far that it interferes with wrist flexion. The therapist should ensure that the splint does not position the wrist in radial or extreme ulnar deviation.

The therapist forms the thumb trough by positioning the thumb in palmar abduction and stretching the plastic to form the C bar. The therapist should distribute pressure along the thenar eminence, thus providing optimal positioning of the thumb and avoiding hyperextension of the MP joint. The thumb trough should extend just past the IP joint of the thumb but should leave the tip of the thumb free for sensory contact during grasp (Figure 16-14). The finished splint should allow the index and middle fingers to contact the tip of the thumb. The therapist should place a strap across the dorsum of the hand. If necessary, the therapist should also place a strap across the thumb trough.

Figure 16-14 The thermoplastic thumb splint should allow the index and middle fingers to contact the tip of the thumb during grasp.

Sometimes during fabrication it is necessary to modify a small area. This can be especially challenging when one is working on a small curved splint. If the therapist wants to use hot water but does not want to risk losing the overall shape, a kitchen baster or eye dropper can be used to draw up hot water and place it repeatedly over the target area [Hogan and Uditsky 1998]. A device called the Ultratorch (available through UE TECH) is a fine spot heater that allows pinpoint modifications, even with 1/16-inch material [Armstrong 2005].

Precautions

The pressure to position the thumb should be directed below the MP of the thumb to prevent stress and possible dislocation of this joint. The splint should also fit snugly into the thumb web space. The therapist must watch for signs of skin irritation and pressure, a problem that is most likely to occur in the thumb web space or at the MCP joints of the fingers. In addition, the therapist should monitor the child for circulation and nerve compression problems caused by an ill-fitting splint.

Wearing Schedule

The child should wear the thumb splint while participating in occupations and activities that require grasp, manipulation, and release. Although it is primarily a functional splint, the thumb splint can also be worn during the day to prevent the opponens muscle from remaining in a fully shortened position. If contractures are a concern, the child may also need to wear a resting hand splint to provide further stretch of the thenar muscles.

The therapist should give the child opportunities to use the thumb actively, especially just after the splint is removed to take advantage of the elongation of the thenar muscles. As the child gains active control of thumb abduction, the therapist should reduce wearing time of the splint so that the child’s own muscle strength increases. Activities should be planned while the splint is off that will provide opportunities to practice active thumb movements so that motor learning can occur.

Soft Thumb Splints

The soft thumb splint allows more movement of the intrinsic muscles of the hand and active movement of the thumb. The soft thumb splint restricts palmar adduction of the thumb but does not prevent it. The therapist can fabricate the splint from neoprene or purchase a prefabricated neoprene splint available in sizes ranging from infancy to youth (Figure 16-15). A thumb splint made of neoprene has the advantage of providing neutral warmth, which may have an inhibitory influence on hypertonicity.

Figure 16-15 Neoprene thumb splints. (One supplier of such splints is the Benik Corporation, 11871 Silverdale Way Northwest, Suite 107, Silverdale, WA 98383 [1-800-442-8910].)

If purchasing a neoprene thumb splint, the therapist should consider whether the splint has a Velcro closure. A thumb splint that slides over the fingers and thumb may be more difficult to apply. The tone and positioning splint (www.sammonspreston.com) is made of neoprene for thumb positioning and forearm supination. It provides constant low-level stretch to the forearm pronators.

Adaptations

Some children have difficulty maintaining an open thumb web space with a neoprene splint because of moderate to severe hypertonicity. The therapist can make a web space opener out of elastomer, thermoplastic pellets, or Permagum that is worn under the neoprene splint. Elastomer, thermoplastic pellets, and Permagum are described under the “Adaptations” section earlier in this chapter. Hogan and Uditsky [1998] provide a detailed description of the application of elastomer.

Another adaptation is the attachment of a crayon or marker to the neoprene thumb splint. The marker should be positioned so that the tip will contact the paper while the forearm is in neutral or slight supination (not pronated). A Velcro strap can secure the marker, and Sticky Tac (for mounting pictures on walls) or rubber bands above and below the attachment can keep the marker from sliding. A separate holder could also be made of thermoplastic material if necessary. One such adaptation to a Benik glove is described by Thompson [1999].

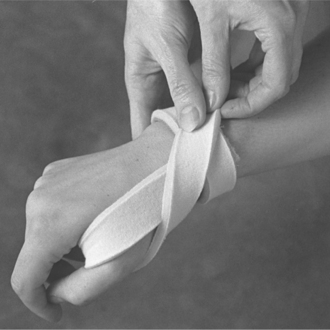

Process to Fabricate a Soft Thumb Splint with Thumb Loop

The therapist makes the wrist band and thumb loop from neoprene (Figure 16-16). The strap that forms the thumb loop should be wide enough to support the thumb but not so wide that it buckles or wrinkles in the thumb web space. The strap that forms the wrist band should be wide enough to secure the thumb loop, remain in place on the wrist, and distribute pressure. This strap should be long enough to form an adequate overlap to secure the Velcro. The therapist can determine the specific dimensions by placing strap material on the child’s arm and hand to measure lengths and widths and determine the desired angle of pull.

Pattern

The therapist should make the wrist band to overlap on the volar side of the wrist. The length of the thumb loop should be the distance from the proximal edge of the wrist band, around the thumb, and back around to the point of origin.

Forming the Splint

Neoprene heat-sensitive tape can be used to bond the pieces because it is very difficult to sew. (With the proper needle, thread, and variable-tension sewing machine, sewing neoprene can be done.) First, the therapist should attach hook-and-loop Velcro to each end of the wrist band that is designed to overlap on the volar side of the forearm. To form the thumb loop, the therapist should attach one end of the thumb loop to the dorsal portion of the wrist band. The therapist then attaches loop Velcro to the free end of the thumb loop and hook Velcro to the dorsal portion of the wrist band (partially covering the origin of the thumb loop).