Splinting on Older Adults

1 Describe special considerations for splinting older adults in different treatment settings.

2 Identify age-related changes and medical conditions that may affect splint provision.

3 Explain how medication side effects may affect splint design and care instructions for older adults.

4 Recognize how an older adult’s occupational performance may influence splint use and design based on the following client factors:

• Neuro-musculoskeletal functions:

• Cardiovascular and hematological functions

• Digestive, metabolic, and endocrine functions

5 Be familiar with a variety of prefabricated splint options and materials available to custom design splints.

6 Describe factors that influence methods of instruction for an older adult and caregiver.

The age of 65 has been used as the marker in establishing policies for the older adult [Chop and Robnett 1999]. According to the Administration on Aging, by 2030 (when the baby boomer generation reaches 65) the older adult population will double and represent 20% of the total population [DHHS 2003]. Although most older adults live independently, approximately 4.5% reside in nursing home facilities (with the percentage increasing with time).

Regardless of health status, 27.3% of community dwelling older adults and 93.3% of institutionalized Medicare beneficiaries have some limitation in function that prevents them from being fully independent in activities of daily living (ADL) [DHHS 2003]. Thus, approximately 7.2 million individuals aged 65 and older have chronic illnesses and disabilities that require supportive care for ADL [Binstock 2001]. Therapists often provide therapeutic interventions for older adults to improve functional status. Interventions include the design and fabrication of splints. Aging may affect hand dexterity [Lewis 2003], and older adults may benefit from splinting to improve occupational performance.

Note: This chapter includes content from previous contributions from Serena M. Berger, MA, OTR; Maureen T. Cavanaugh, MS, OTR; and Brenda M. Coppard, PhD, OTR/L.

Fundamental principles of evaluation, design, and fabrication of splints do not change as people age. Therapists do, however, need to be aware of special considerations necessary to accommodate unique needs of the older adult. When designing a splint for an older adult, the therapist should consider the special needs of the older adult, the goal of the splint, and the splinting supplies available. A splint for an older adult should (1) prevent undesirable motion while permitting normal motion, (2) provide adequate stability, (3) decrease energy expenditure when worn, (4) provide safe distribution of force, (5) be comfortable, (6) be applied and removed easily, (7) be economical, (8) be durable, (9) be easily modified [Good and Supan 1992], and (10) be easily cleaned.

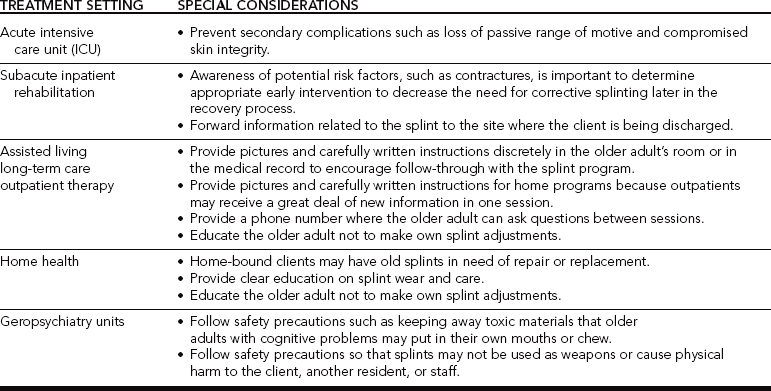

Influence of Different Treatment Settings on Splint Design

The older adult’s environment is also an important consideration for clinical decision making. Therapists treat older adults in multiple settings.Box 15-1 provides a summary of considerations for the design of splints for individuals in any treatment setting.Table 15-1 presents specific considerations for different settings. The older adult’s living situation (e.g., independence in a community versus dependence in a long-term care setting) is important when the therapist determines the most appropriate splint. For example, an 80-year-old woman with osteoarthritis who performs her own self-care and requires the use of her hands throughout the day may benefit from a thumb carpometacarpal (CMC) immobilization splint to improve her daily function.

In contrast, a long-term care resident who has had multiple cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs) may require splints to maintain sufficient range of motion (ROM) to be dressed and bathed. Hand ROM is necessary to prevent skin maceration in the palm caused by sustained full-finger flexion. Therapists who treat older adults during the acute stage of an illness must be aware of risk factors toward preventing secondary complications such as loss of passive ROM, edema, and skin breakdown.

Age-Related Changes, Medical Conditions, and Splint Provision

Older adults’ body systems are vulnerable to chronic medical conditions. For instance, someone who has been referred for a hand splint following a CVA may have other conditions prevalent with aging, such as diabetes and osteoarthritis. In addition to obtaining a thorough medical history to determine the appropriate goals for a splint, the therapist needs to be familiar with how different medical conditions concurrently affect hand function.

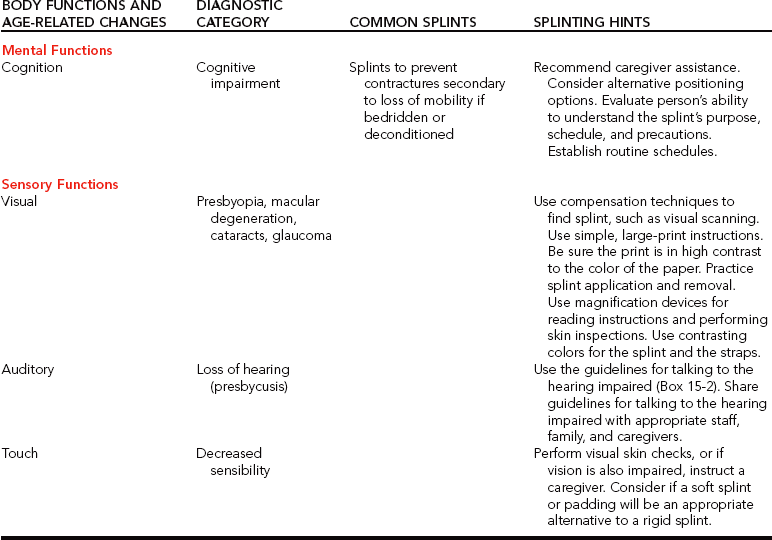

Table 15-2 provides a summary of age-related changes and medical conditions that affect the design and approach to splinting. The following client factors [AOTA 2002] are based on selected classifications from the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [WHO 2001] as they relate to considerations for splinting older adults.

Table 15-2

Summary of Age-related Changes and Medical Conditions Impacting Splint Design or Provision

Mental Functions (Cognition)

The therapist assesses the cognitive status to determine the older adult’s ability to follow a splint-wearing schedule and to be aware of splint problems. Working memory impairment may prevent the older adult from recalling the splint’s storage location or application procedure. Sometimes a therapist can ascertain memory problems by noting how an older adult follows directions during splint fabrication. If memory is a problem, the therapist establishes a routine schedule for splint wear and care, fabricates a simple splint, and labels the splint for easy application.

If the older adult has significant cognitive impairments, the therapist recommends assistance. The therapist must educate any new caregiver about the splint’s purpose, wearing schedule, care, correct application, and possible problems. Individuals with later-stage dementias often posture in flexed positions and thus the caregiver may require recommendations to maintain skin integrity. If there are cognitive impairments, or if a caregiver is involved, the risks versus the benefits of a splint must be carefully weighed against alternative positioning (such as the use of pillows or dense foam wedges). In addition, the therapist may consider using D-ring straps for a person with dementia who is constantly trying to remove the splint.

Sensory Functions

Of people over age 65, researchers found that 17.2% have some type of visual impairment related to developing functional limitations [Dunlop et al. 2002]. Decreased vision can also play a role in noncompliance of splint wear. For example, some older adults may be unable to apply their splints because of poor figure/ground discrimination. Older adults may also have difficulty seeing straps and Velcro as well as inspecting their skin. Using colored thermoplastic splinting material and contrasting colored straps may assist the older adult who has poor visual discrimination. Bright colors may prevent the splint from being easily lost or mistakenly sent to the laundry.

When receiving splint instructions by demonstration, older adults who have correctable vision should wear their glasses. The older adult demonstrates to the therapist proper splint application and removal. The therapist provides simple large-print instructions. A high contrast of the ink and paper is helpful. The use of magnification devices can also help with reading instructions and with performing skin inspection.

For older adults who have macular degeneration (e.g., blurred or loss of central vision), the therapist encourages the use of compensatory techniques during application and removal of the splint and during skin inspections. Compensatory techniques include eye scanning, head turning, and placement of the splint or hand into the field of vision.

Auditory System

Approximately 25% of older adults between 65 and 74 years of age, 50% of older adults age 75 or older, and 65% of those age 85 and older describe difficulty with hearing [American Federation for Aging Research 2004]. Hearing impairment influences verbal explanations and statements. Sometimes hearing problems can be detected during the initial interview or during splint fabrication. Therapists should not rely solely on printed information to relay instructions because some older adults may be unable to read or have visual impairments that make reading difficult or impossible. The therapist may need to use more tactile cues when positioning the person for splinting. When talking to a person who is hearing impaired, the therapist should use the guidelines outlined inBox 15-2.

Touch

Somatosensory research has demonstrated a decline in two-point discrimination with age [Stevens and Patterson 1995]. Because the decline is gradual over the life span, older adults may not be aware of their diminished sensibility. Because vision is the primary sense used to compensate for decreased tactile sensation, when both sensory functions have declined the older adult is at greater risk for compromised skin integrity.

Tactile sensation may become impaired secondary to poor positioning of older adults with limited mobility. Decreased sensation may contribute to compression neuropathies of the median or ulnar nerves. Cubital tunnel syndrome, a compression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow level, may result from constant pressure on flexed elbows while sitting in a wheelchair or from prolonged bed confinement. A well-padded elbow splint with the elbow flexed 30 to 60 degrees prevents further pressure to the nerve [Clark et al. 1998, Blackmore 2002].

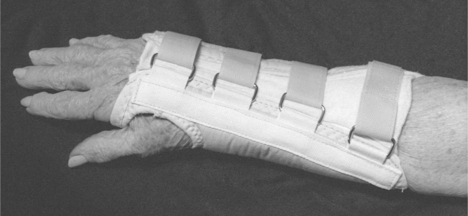

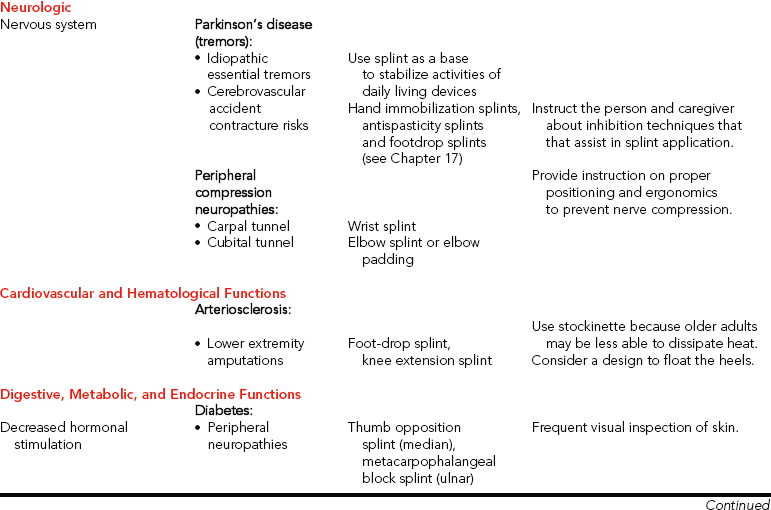

Prefabricated soft elbow pads are another option. Compression of the median nerve at the wrist may be due to prolonged wrist flexion posturing or secondary to an associated medical condition, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or diabetes. A prefabricated wrist splint with D-ring straps is easier to don and can be used to prevent nerve compression (Figure 15-1; and see Chapter 13 for further discussion of these conditions).

Neuro-musculoskeletal Functions

One of the most impacted body systems affected by age is the skeletal system. Osteoporosis and osteoarthritis (OA) are common diagnoses that often require splinting as part of the intervention process. Osteoporosis is a gradual loss of bone density that begins as young as age 35 [Boughton 1999]. After menopause, the rate of bone loss for women increases [Barzel 2001], and the distal radius is especially vulnerable to fractures [Bostrom 2001]. A common fracture of the distal radius is called a Colles’ fracture, which often occurs because of accidental falls [Nordell et al. 2003].

Although wrist fractures are usually treated in an outpatient setting, older individuals may at the same time fall and sustain a hip fracture, which initially requires inpatient therapy. Sustaining a Colles’ fracture can be associated with functional declines in physical performance in hand strength and walking speed [Nordell et al. 2003]. A volar wrist splint is generally indicated after removal of an arm cast or external fixator for immobilization (see Chapter 7). As the fracture heals, the splint goal may change to one of mobilization (which can be achieved by serial adjustments to improve wrist extension). It is also important to determine if there are other etiologies causing upper extremity impairments. For example, a thorough evaluation for a client referred with a wrist injury may reveal preexisting sensory loss in the digits due to compression of cervical nerve roots caused by OA. The sensory loss might otherwise have only been associated with the wrist fracture.

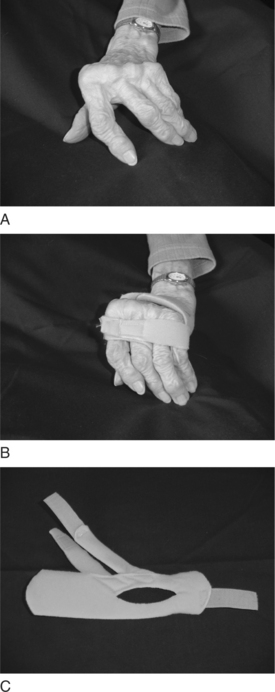

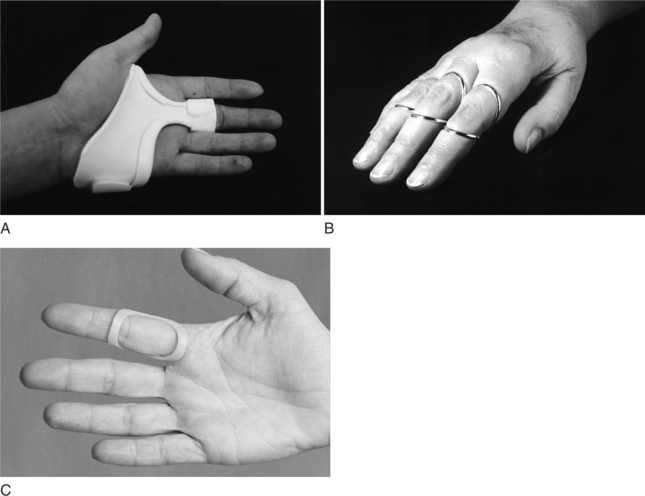

Another condition that affects the skeletal system is OA. Women are more frequently affected, and the initial onset typically occurs between ages 50 and 60 [Melvin 1989, Rozmaryn 1993, Hellman and Stone 2004]. Primary OA results from idiopathic or known causes. Secondary OA results from congenital joint abnormalities; genetics; infections; and metabolic, endocrine, or neurological disorders [Beers and Berkow 1999]. Most older adults have evidence of some cartilage damage [Bland et al. 2000]. Hand joints are more frequently affected by primary OA [Rozmaryn 1993, Bozentka 2002], which is characterized by enlarged distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints (Heberden’s nodes) and enlarged proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints (Bouchard’s nodes). The nodes typically cause more discomfort in the index finger because of the demands placed on the joints during activities that require pinch. An immobilization splint for the DIP joint is a conservative measure to decrease pain (Figure 15-2). Surgical fusion may be warranted for more advanced cases.

Figure 15-2 Enlarged DIP joints from osteoarthritis may become painful and benefit from immobilization to decrease pain.

OA of the thumb at the CMC joint is another common reason for a splint referral. Initial conservative management usually requires a hand-based thumb immobilization splint (see Chapter 8). Individuals with this condition must be educated in joint protection techniques and instructed with methods to balance activities throughout the day to break the pain cycle. As discussed in Chapter 8, there are different approaches to splinting arthritic hands. The most prevalent approach is to fabricate a removable hand-based splint to immobilize only the CMC joint.

Researchers evaluated the effectiveness of a short opponens splint (only the CMC is immobilized) compared to a long opponens splint (the wrist, CMC, and thumb metacarpophalangeal (MP) are immobilized). Researchers found that 42% of the subjects who wore the short opponens splint reported performance of ADL to be easier. Fifty-one percent of the subjects reported performance of ADL to be the same when wearing the short opponens splint. Some subjects (7%) found ADL performance more difficult while using the short opponens splint. Only 16% of subjects who wore the long splint found activities easier to perform [Weiss et al. 2000]. The researchers concluded that splinting is effective for pain reduction and helps to reduce subluxation in the early stages of OA.

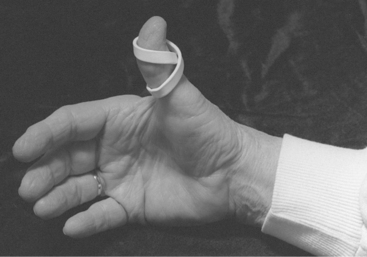

Chronic flexion of the thumb MP joint, or an adduction contracture, can lead to a hyperextended interphalangeal (IP) joint. This can be conservatively treated with a figure-of-eight splint to improve stability and function of the thumb (Figure 15-3). If the older adult needs to use a walker and has thumb pain or a weak grip, a prefabricated walker splint can be used to decrease stress to the thumb (Figure 15-4).

Figure 15-3 A tri-point figure-of-eight design can stabilize the thumb IP joint to prevent hyperextension during pinch.

Figure 15-4 Walker splint: a functional splint for persons with limited or painful grasp. (Original design by Beth Beach, OTR.) [From Sammons-Preston Rolyan (2004). Professional Rehab Catalog. Bolingbrook, IL.]

Sammons-Preston RolyanOA may also affect the cervical spine and result in sensorimotor deficits in the hand. The therapist checks the older adult’s medical history for cervical involvement in order to distinguish peripheral nerve from cervical nerve root compression. In older adults who have multiple medical conditions, the source of decreased sensorimotor function in the hand requires careful medical evaluation.

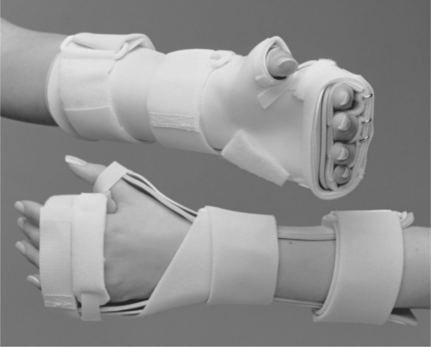

Deformities that result from RA may be seen in older adults. However, the most common onset of this systemic condition is in women typically between the ages of 40 and 50 [Pincus 1996]. Mitt splints lined with Plastazote can be helpful for older adults who have residual painful deformities and fragile skin (Figure 15-5). Additional examples of splints for RA are included in the chapters on wrist, hand immobilization, thumb, and mobilization splints.

General Mobility

Many older people become sedentary, which decreases aerobic capacity, muscle strength, ROM, and coordination [Lavizzo-Mourey et al. 1989, Evans 1999]. The therapist should be cautious that splints do not result in unnecessary immobility or loss of engagement in activity. Among persons over age 65 living in the community, 30% fall each year [Gillespie et al. 2004]. Associated injuries include lacerations and bruising; scalds and burns; arm, wrist, hand, and hip fractures; and concussions [Lavizzo-Mourey et al. 1989, Daleiden 1990, Potempa et al. 1990, Carter et al. 2000].

The percentage of falls in institutions is even higher [Gillespie et al. 2004]. The risk for falls increases with age, with one out of two older adults over age 80 experiencing a fall every year [Crane 2002]. If a splint is out of reach, the older adult may not be able to reapply it because of difficulty with ambulation and reach. Maintaining a consistent storage location within reach and easy walking distance is important.

The splint design should be simple. The older adult may be unable to manipulate multiple straps to apply a splint by using one hand. Riveting one end of the strap to the splint or using adhesive straps prevents their removal and loss. Attached straps reduce the risk of the older adult falling while attempting to retrieve a dropped strap.

Neurologic System

Progression of cardiovascular disorders may lead to a CVA resulting in abnormal tone on one side of the body. When making a splint for an older adult with abnormal tone, it may be important to also consider principles involved with splint design related to a coexisting condition such as OA of the thumb CMC joint. In addition, orthokinetic properties of materials should be cautiously selected because they may affect tone (see Chapter 14).

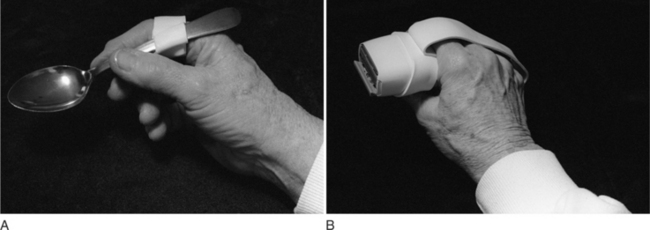

Some neurologic conditions cause tremors. Tremors may be associated with Parkinson’s disease, idiopathic essential tremors, or tremors secondary to medication side effects. Splints may be used as a base to hold assistive devices to improve self-care function in the presence of tremors. An adaptation may be made to a splint that is required for a coexisting diagnosis. A splint may be made solely to position a self-care utensil, such as a spoon, or to stabilize a pen to write (Figure 15-6).

Cardiovascular and Hematologic Functions

Many older adults who receive therapy have cardiovascular disease, which may be the primary or secondary reason for referral. For someone who has cardiovascular disease, the therapist should educate the older adult to store the splint in close proximity in order to conserve energy. When fitting someone with a lower extremity splint, precautions for peripheral vascular disease should be observed. Another age-related change is a decreased small vessel supply [Saxon and Etten 1994, Bottomley and Lewis 2003].

The temperature of the splint material should be carefully checked, and a double layer of stockinette should be considered instead of applying warm splint material directly to the skin. Older adults who have less ability to dissipate heat are vulnerable to burn or torn skin. If older adults have decreased cognition and thin skin, they may not be aware of the potential for burns. Poor circulation also results in delayed wound healing after skin breakdown.

Digestive, Metabolic, and Endocrine Functions

Dehydration, alcohol abuse, chronic disease, or poor diet in older adults may cause nutritional deficiencies. Sensory testing is carefully completed with individuals who have digestive disorders and nutritional deficiencies, including pernicious anemia, because they may also present with impaired nerve function. Poor wound healing may be the result of a poor nutritional status. The condition of the skin and nails is observed to determine appropriate materials and splint care.

Endocrine System

Diabetes mellitus (DM), a disorder of the endocrine system, is a common secondary diagnosis affecting up to 15.1% of older adults [DHHS 2003]. There are two types of diabetes. Type 1 is insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), with onset before age 30. Type 2 is non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM), with onset more typically after age 30 [Beers and Berkow 1999]. Individuals with long-standing diabetes have an increased incidence of other conditions that must be considered before a splint is made.

A careful sensory evaluation will help determine whether there are peripheral neuropathies in the fingers or toes. If sensation is diminished, pressure caused by a splint may not be perceived by the older adult and may lead to skin breakdown. Straps must never cause constriction, especially if there is associated peripheral vascular disease. These considerations are particularly important when someone with diabetes is referred for a foot-drop splint, a knee extension splint after a below-the-knee amputation, or a finger flexion contracture secondary to a CVA.

Individuals with diabetes are at greater risk of associated conditions [Cagliero et al. 2002] that may require splints for the upper extremity [Chammas et al. 1995]. There is an increased incidence of carpal tunnel syndrome in persons who are diabetic. Conservative management includes a wrist immobilization splint with the wrist positioned in neutral. This splint is worn at night. Stenosing tenosynovitis may occur at the first dorsal extensor compartment on the radial aspect of the wrist. This is called de Quervain’s tenosynovitis, which is managed with a thumb immobilization splint on the wrist and thumb (see Chapter 8).

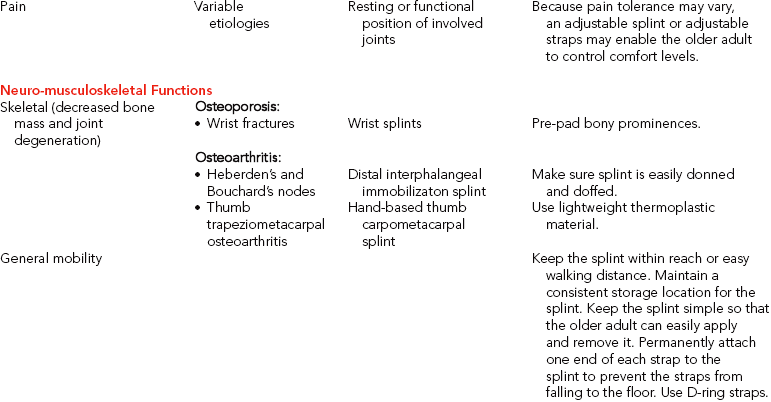

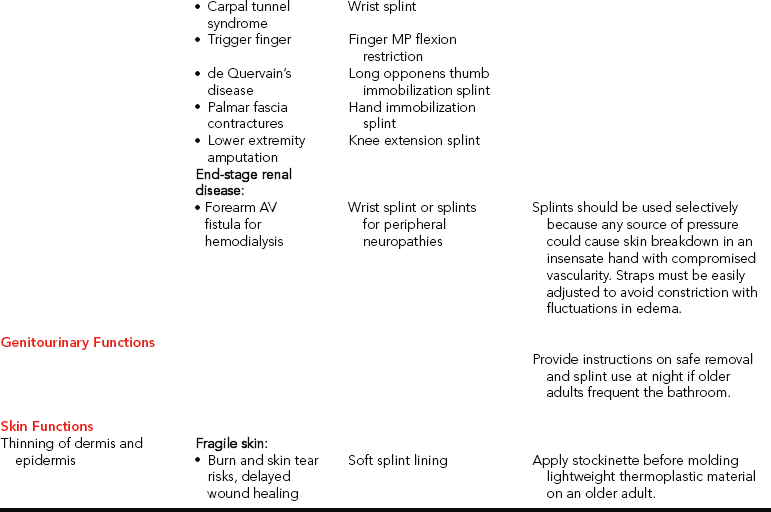

Trigger finger is another form of stenosing tenosynovitis that occurs during middle age and that has an increased incidence associated with diabetes. Conservative management may include a splint to restrict MP flexion [Fess et al. 2005] to decrease inflammation in the distal region of the palm near the involved digit. The therapist may decide to (1) custom fabricate a splint (Figure 15-7A), (2) take measurements for the purchase of a custom-manufactured silver ring splint (Figure 15-7B), or (3) order a prefabricated splint (Figure 15-7C). Considerations for this decision include the availability of materials, reimbursement source, and client input.

Figure 15-7 (A) A splint to restrict MP flexion for trigger finger. [From Fess EE, Gettle K, Philips CA, Janson JR (2005). Hand and Upper Extremity Splinting: Principles and Methods, Third Edition. St. Louis: Elsevie/Mosby.] (B) Siris™ Trigger Splint. [Courtesy Silver Ring Splint Company.] (C) Oval-8™ for trigger finger. [Courtesy 3-Point Products, Stevensville, Maryland]

A flexion contracture of the palmar fascia may resemble Dupuytren’s disease and is another example of a soft-tissue condition associated with diabetes [Cagliero et al. 2002]. Idiopathic Dupuytren’s disease is most common in Caucasian men about 50 years of age with Northern European heritage [McFarlane and MacDermid 2002]. These individuals have limited extension of their fingers or thumbs, with nodules at the palmar base of the involved digits. A splint is not effective in preventing contractures because the contracted tissue of Dupuytren’s disease does not respond to low-load prolonged stress. Splinting with a hand immobilization splint to regain extension of the digits is appropriate only after a surgical release of the fascia (see Chapter 9).

Kidneys are part of the urinary system but have an endocrine function. When treating individuals with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), it is important to carefully determine the location of the subcutaneous arteriovenous (AV) fistula (typically on the forearm) used for vascular access for hemodialysis. As a result of the radial artery anastomosis with the cephalic vein [Beers and Berkow 1999], vascularity distal to the AV is compromised and can result in edema and peripheral neuropathies that affect sensorimotor hand function [Liu et al. 2002]. Splints should be used selectively because any source of pressure could cause skin breakdown in an insensate hand with compromised vascularity.

Genitourinary Functions

If an older adult needs to wear a splint during sleep periods, the history should include urinary function. Older individuals often go to the bathroom two to three times per night due to medications such as diuretics, changes in sphincter function in females, or prostate conditions in men. With splint wear during sleep, it is especially important that the splint is easy to don and doff for bathroom hygiene.

Skin Functions

Aging of the integumentary system includes thinning of the epidermis and dermis. Older adults with little subcutaneous fat may be more susceptible to pressure sores. Fragile older adults are more likely to have skin tears. A soft splint or padding to line the splint should be considered.

Medications and Side Effects

Many older adults take medications that cause side effects [Skidmore-Roth 1997] that may affect splint provision. Corticosteroids are commonly prescribed for chronic conditions such as RA and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Long-term steroid use can lead to ecchymosis (bruising), osteoporosis, and thin skin that is vulnerable to skin tears. Long-term steroid use can also lead to delayed wound healing. Anticoagulants, such as heparin, are prescribed for collagen vascular disorders. Their side effects include increased risk of ecchymosis and edema from minor soft-tissue trauma.

Antihistamines for respiratory conditions and psychotrophic medications for depression can cause tremors. When designing a splint for older adults who take these medications, the additional risks of fragile skin, osteoporosis, bruising, edema, or tremors need to be factored into the splint design. In older adults, sleep medications may affect splint wear. For example, the person may not notice problems if the splint becomes uncomfortable during the night, thus increasing the possibility of skin breakdown. In addition, the older adult may be noncompliant with the wearing schedule and wear the splint too long [Knauf 1999].

Purposes of Splints for Older Adults

The splints prescribed for the discussed medical conditions are not unique to older adults. In the older population, however, there is an increase in the effects of chronic health problems. Neurologic and orthopedic problems are also more common in this group [Lewis 2003]. Therapists should obtain client input in order for the splint to maximize desired outcomes, including satisfaction and occupational performance [McKee and Rivard 2004]. The purposes of splinting an older adult may include, but are not limited to, the following:

Range of Motion

The design of a splint should always allow full ROM of noninvolved joints. Serial mobilization splinting is generally the preferred method to improve decreased ROM for an older adult. A splint that is serially adjusted to improve ROM is easier to manage because the therapist has better control over the amount of force applied. For example, a volar wrist extension mobilization splint after a distal radius fracture may require several progressive adjustments to improve wrist extension [Laseter 2002] (see Chapter 7).

Pain Reduction

With acute and chronic conditions, one goal of splinting is to reduce pain by providing support and rest to the involved joints. For example, for an older adult who has RA the purpose of the splint is primarily to reduce pain by stabilizing the involved joints [Merritt 1987, Ouellette 1991]. The therapist uses different splint designs according to the stage of the arthritis and the joints involved. However, “the use of splints to rest the hands during periods of pain and inflammation is controversial” [Ouellette 1991, p. 68].

Intermittent periods of rest (i.e., three weeks or fewer) appear to be beneficial, but prolonged immobilization for longer periods may cause loss of ROM [Ouellette 1991]. In addition to the design of the splint to rest specific joints, the wearing schedule can provide the appropriate balance between rest and activity. The hand-based thumb immobilization splint worn for CMC osteoarthritis is an example of a splint removed periodically for ROM and reapplied during activities that otherwise cause pain and stress to the joint.

Improvement of Occupational Performance

A splint may improve or maintain an older adult’s function. When possible it is preferable to adapt the environment rather than restrict ROM in a hand splint. For example, a figure-of-eight finger splint on a pen allows the older adult to continue writing. Rather than making a wrist splint for use during shaving, the therapist makes adaptations from thermoplastic material on an electric razor to allow an older adult to remain independent (Figure 15-6B). Using hand splints during ADL is extremely awkward when sensory input is impeded [Redford 1986].

Specially adapted splints that help promote function are available. Older adults who have RA may benefit from hand splints that immobilize joints rather than mobilize them. If the wrist is weak, a wrist immobilization splint provides external stability to improve distal finger function. If the functional deficit is due to tremors, as with Parkinson’s disease or as a side effect of medications, the elbow can be stabilized on a table surface. Modification of an ADL device to decrease dexterity requirements can be used in addition to elbow stabilization to improve function.

Contracture Management

Loss of mobility and neurologic conditions place an older adult at increased risk of developing contractures [Portnoi and Ramzel 2001]. Changes in the older adult’s connective tissue and cartilage increase the risk of contractures, especially during inactivity [Portnoi and Ramzel 2001]. Goals may be to prevent further contracture, decrease pain, or enable better skin care. It is important to weigh the risks of a splint that causes additional complications, such as contributing to skin breakdown.

If the splint is applied while passive ROM is still within normal limits, it may be possible to prevent a contracture. If the loss of passive ROM is recent, mobilization splinting may improve ROM and correct the contracture. An example is a foot-drop splint to gradually position the ankle at 90 degrees after a loss of active ankle dorsiflexion. In addition, therapists commonly use hand immobilization splints to prevent further deformity when there is a loss of active hand or wrist ROM.

Edema Management

When there is loss of active ROM combined with diminished circulation, edema can lead to secondary shortening of soft tissue. It is important to prevent edema when possible through such techniques as elevation and active ROM. The edematous hand is positioned in a splint to counteract adaptive tissue shortening and residual contractures. The position of deformity caused by edema results in thumb adduction, MP extension, and IP flexion. To prevent this deformity, the wrist is positioned in an intrinsic plus position.

The intrinsic plus position consists of 20 to 30 degrees of extension, the thumb in palmar abduction, and the fingers in MCP flexion with the PIP and DIP joints in extension [Strickland 2005]. Additional adjunctive techniques will be necessary to treat the edema unless active ROM returns. Wearing a pressure garment, such as an Isotoner glove, at the same time as the splint may assist in controlling edema. If the noninvolved side of an older adult also appears edematous, a systemic cause—such as congestive heart failure (CHF)—should be considered, in which case a physician may prescribe diuretic medications to decrease fluid retention.

Protection of Skin Integrity

The combination of impaired cardiovascular function and changes associated with aging, such as diminished sensation and thinning of the dermis and epidermis, creates the risk for loss of skin integrity. The heel is the most vulnerable area for skin breakdown in the lower extremity. Use of a foam positioning splint or foot-drop splint with the heel elevated from the splint surface may prevent pressure sores from developing on the heel. Older adults who hold their hands in a fist position or continually flex their elbows, knees, and hips also create an environment conducive to skin breakdown.

The accumulation of perspiration within the skin folds allows bacteria to grow [Redford 2000]. This constant posturing and the resulting bacteria growth may cause joint contractures, skin maceration, and possible infection. A splint made of molded thermoplastic, a hand roll, or a palm protector positions the involved joints in submaximum extension (allowing adequate hygiene of the hand). To accomplish any of these goals, the therapist obeys the following rules:

• A splint should not impede function unnecessarily. For example, the splint should not prevent an older adult from safely grasping an ambulation device or interfere with wheelchair propulsion.

• A splint should not exacerbate a preexisting condition. For example, an older adult who demonstrates a flexor-synergy pattern may wear a functional position splint at night for pain and contracture management. The older adult may also have CMC OA in the thumb. The functional position splint should therefore place the thumb MP and IP joints in extension and the CMC joint in 45 degrees of abduction, midway between radial and palmar abduction. This thumb position differs from that of functional position splints in which the thumb is placed in palmar abduction and opposition to the pads of the index and middle fingers. This midway position may provide more comfort to the thumb CMC joint than palmar abduction [Mallick 1985].

• A splint should not limit the use of uninvolved joints. An example is the arthritis mitt (seeFigure 15-5) splint, which immobilizes the wrist in 20 degrees of extension and the MCP joints in 45 degrees of flexion but allows movement at the PIP joints. When wearing these bilateral splints, older adults are able to complete tasks such as pulling up blankets, ringing doorbells, and holding glasses of water.

Substitution for Loss of Sensorimotor Function

When there is a nerve compression severe enough to cause loss of motor function, a splint may substitute for the lost function. In the case of median nerve compression, a splint may need to position the thumb in opposition to the index finger. If the ulnar nerve is affected, the fourth and fifth MCP joints need to be blocked in slight flexion to prevent a claw deformity with MCP hyperextension and IP flexion of the fourth and fifth digits [Fess et al. 2005]. (See Chapter 13 for more information on splinting for nerve conditions.) In the case of damage to the peroneal nerve, an ankle-foot orthosis can substitute for the loss of ankle dorsiflexion. (See Chapter 17 for more information on lower extremity splinting.)

Splinting Process for an Older Adult

As with any person, the therapist completes a comprehensive rehabilitative assessment to determine whether splinting is indicated. All components of a therapy evaluation are essential for determining an effective treatment plan. (See Chapter 5 for a discussion of a hand examination.) The therapist pays special attention to the cognitive, sensory, physical, and ADL status of the older adult to determine the usefulness of splinting as part of the treatment plan. The results of the evaluation are used to develop a list of problems to be addressed by the treatment plan. Typical goals include those listed in the section “Purposes of Splints for Older Adults.” The therapist documents functional goals in the treatment plan. Additional problems associated with aging (such as decreased visual discrimination, decreased cognition, and hearing impairments) are considered when providing splint instructions for the older adult or caregiver.

During the initial evaluation, the therapist notes any current use of adaptive devices and techniques. For example, an older adult may already have a splint for a chronic condition such as RA. The therapist evaluates the splint for its functional purpose, proper fit, and wearing schedule.

Observation during the assessment is vital to determine the purpose and to select the design of the splint. It is important to observe and assess movement of the extremities in relation to the trunk. For example, an older adult who has hemiplegia with a spastic upper extremity may be wearing a hand splint that is resting on the chest and causing pressure.

Material Selection, Instruction, and Follow-up Care

The choice of thermoplastic splinting material, straps, and padding varies and is based on the older adult’s needs. For instruction and follow-up care, many factors influence the older adult’s needs, including the following:

• Home, long-term care, hospital settings, assisted-living facilities, subacute, hospice, or adult day care

• Severity of contractures: mild, moderate, or severe

• Skin integrity: fragile skin, open wounds, or pressure areas

• Level of care: home health aid assistance, full- or part-time family or caregiver assistance, or independent functioning

Environment

Older adults may reside in a variety of settings, including homes, condominiums, apartments, independent-living facilities, or assisted-living facilities. Other older adults may live permanently or temporarily in hospitals or in assisted-living or other long-term care facilities. The older adult’s environment affects the selection of strapping and thermoplastic splinting material properties and follow-through. For example, persons responsible for their own splint follow-through receive complete instructions. For older adults in institutional settings, the therapist provides instructions to all caregivers responsible for the older adult’s care.

Contracture Risk

The level of joint contracture risk affects the splint-wearing schedule. For example, an older adult with spasticity has a high risk of joint contractures and may frequently wear a splint. Older adults who have a low contracture risk with increasing active ROM may decrease wearing time, thus allowing the affected hand to engage in activities. The therapist uses clinical judgment to determine wearing schedules and completes frequent monitors to adjust wearing schedules according to the older adult’s needs.

Skin Integrity

Skin integrity can influence the choice of splint materials. For example, the therapist uses soft, longer, and wider strapping for an older adult who experiences edema fluctuations. The therapist uses a splint made of soft material for a person who has fragile skin. In addition, the therapist may apply polypropylene stockinette under a splint to absorb perspiration because this type of stockinette material is more effective than cotton at wicking the moisture away from the skin.

Level of Care and Impairments

Anticipated older adult and caregiver compliance affects material choice and splint design. For example, the therapist uses a simple splint design for an older adult receiving care from various health care providers in a long-term care facility. The therapist uses a brightly colored thermoplastic material that has contrasting colored straps for an older adult who has difficulty with figure/ground discrimination. Older adults who have hearing loss need written directions. These approaches increase compliance with and tolerance of the splint-wearing schedule.

Selection of Splinting Materials

Depending on client considerations and the goal(s) of the splint, the optimal material may be rigid thermoplastic, lightweight, multiperforated, less rigid thermoplastic, or soft fabrics and foams. Selection of a low-temperature thermoplastic splinting material is determined by the following: (1) the extent to which an older adult’s joint can assume and maintain a gravity-assisted position, (2) the size of the splint, (3) the performance requirements of the splint, (4) the padding requirements, (5) the weight of the splinting material, and (6) the therapist’s skill level.

If the older adult is physically and cognitively able to hold the limb in the desired splinting position, the therapist uses a splinting material with high drapability and moldability to ensure an intimate fit. The therapist positions the older adult’s extremity to ensure that gravity assists in the draping of the material over the extremity. Splinting material with a high degree of conformability allows detailed molding for a precise fit, thus increasing comfort and decreasing the risk of splint migration and friction over bony prominences.

Some older adults cannot assume positions that allow gravity to assist in the molding of splints. Older adults may be anxious and may respond to the stretch applied during splinting by exhibiting increased tone. In such situations, or during the fabrication of large splints, material with resistance to drape and memory is helpful. A material that lightly sticks to stockinette placed on the older adult facilitates antigravity splinting (see Chapter 3). Preshaping techniques are also helpful when splinting an older adult with diminished cognition or abnormal tone.

Thinner thermoplastic materials (e.g., 3/32-inch, 1/16-inch) are less rigid. The therapist should select the thinnest material that can perform effectively. Minimizing the weight of a splint increases comfort and enhances compliance (Figure 15-8). The more contoured the splint is to the underlying shape the greater the strength. Older adults usually appreciate lightweight splints. These splints may be perceived to be more comfortable.

Another option is to custom fabricate or purchase a prefabricated soft splint. Prefabricated splints may be made of soft material or foams such as Plastzote. An older adult’s hand may be adequately positioned by sewing a soft splint with materials such as neoprene or Velfoam (Figure 15-9).

Strapping Material

Wide, soft, foam-like strapping material distributes pressure over more surface area than thin, firm straps. The softer strapping accommodates slight fluctuations of edema. In addition, fragile skin tolerates soft straps well. Neoprene or Velfoam materials are good choices for straps. Neoprene and Velfoam straps can be easily cut to the desired width. They can also be fringed to decrease pressure against skin. In order to prolong the durability of soft strapping material, it is beneficial to sew standard Velcro loop over the area where Velcro hook will attach. For older adults who have fragile skin, the therapist designs the Velcro loop strap to completely cover the Velcro hook on the splint surface. This prevents abrading the older adult’s skin or catching the splint on clothing and blankets. The use of pre-sewn self-adhesive Velcro straps reduces the loss of the strap.

There are advantages and disadvantages of using D-ring straps. An advantage is that D-ring straps provide mechanical leverage to effectively tighten the strap. Using D-ring strapping may also be an advantage for an older adult who has dementia and does not understand the splint’s purpose, and for similar situations in which the older adult has greater difficulty spontaneously removing the splint. A disadvantage of using these straps is that an older adult who has diminished dexterity may have difficulty threading the strap through the D-ring. However, if the ends of the straps are doubled over or looped the strap will not de-thread through the D-ring.

Padding Selection

The two basic types of padding are open-cell foam (which is absorbent) and closed-cell foam, which is nonabsorbent. Open-cell padding absorbs moisture, is more difficult to keep clean, and can become a breeding ground for bacteria. Before molding, the therapist may apply padding to the thermoplastic splinting material. This ensures a proper fit to accommodate the thickness of the padding.

If the therapist adds padding after the molding process, splint modifications must account for the thickness of the padding. The fabrication of a splint with the addition of 1/16-inch padding results in a splint that is 1/16 inches too tight. Open-cell padding should not be immersed in hot water. When using an open-cell padding (or when using a low-temperature thermoplastic that is pre-padded), the materials can be placed in a resealable plastic bag to keep the padding dry [Sammons-Preston Rolyan 2004].

Closed-cell padding does not hold moisture and is easily washed and towel dried. Plastazote is an example of a foam material available in various thicknesses. The thinner widths can be used to pad a splint, and the thicker widths can be used to fabricate an entire soft splint. Other materials (such as Gel shell pads) can be used if more pressure relief is needed.

Padding may also be required on the outside of a splint. The therapist provides cushioning to the outside of a splint if the splinted extremity rests against another body part. For example, an older adult who has hemiplegia and a flexed upper extremity may rest the splint against the rib cage, or a right ankle splint may press against the left leg when the older adult is side lying.

Choosing the correct thermoplastic, strapping, and padding material is important. Clinical judgment and the ability to make adaptations are important during the splinting of older adults because these clients are most prone to contractures and pressure sores with illness [Bliss and Bennett 2003]. The splint should fit well, achieve the clinical goal, and be acceptable to the older adult and the caregiver.

Technical Tips

Therapists acquire technical skills through practice. During the splinting of an older adult, one or more of the following technical tips may be helpful to the therapist.

• Choose a splinting material that has a slightly longer working time. For example, when fabricating a hand immobilization splint (see Chapter 9), partially pre-shape the hand portion of the resting pan before applying it to the older adult. Complete the pre-shaping on a hand of similar size.

• During the molding process, use Theraband or an elastic bandage to temporarily secure the forearm trough. This activity allows attention to be focused on the contouring of the hand and wrist parts of the splint.

• Pre-pad bony prominences by using circular pieces of adhesive-backed foam or gel padding. Mold the splint over the padding. When molding the splint, place the foam or gel pad inside the splint to ensure intimate congruous contact.

• Use tubular stockinette under the splint to maintain skin hygiene and prevent pressure areas. Loss of skin elasticity and adipose tissue make older persons prone to skin breakdown.

• Use uncoated and self-bonding material for splints if darts or tucks are necessary. Therapists often use this type of design for ankle, knee, and elbow splints.

• Use a coated material for thumb immobilization splints. Often the thumb IP joint is enlarged or deformed, thus making application and removal of a closed circumferential splint difficult or impossible. Use of a coated material allows circumferential wrapping around the proximal phalanx of the thumb. After hardening, the overlap on the proximal phalanx pops open. If self-bonding materials are preferred, use a wet paper towel between the overlapping surfaces to prevent bonding.

• During planning of serial repositioning, select a splint material that has memory.

• For an extremely deformed extremity, make the splint pattern on the opposite extremity and reverse it. If the older adult is unable to cooperate, draw the pattern while he or she is sleeping.

• To ease the splint fabrication process when working among multiple settings, therapists should carry splint boxes with all necessary supplies in them [Swedberg 1997].

Older Adult and Caregiver Instructions and Follow-through

Clear client and caregiver instructions and consistent follow-through are of paramount importance in successful splinting. Many factors influence compliance with a splint-wearing schedule. The person responsible for the splint’s wearing schedule and care is the older adult or the caregiver. SeeBox 15-3 for more information on caregiver and client compliance.

Instructions to Caregivers

Older adults unable to care for themselves need caregiver assistance. Caregivers are family members or staff members from an agency or facility. When fitting a splint to an older adult, the therapist must provide thorough instructions to the caregiver. Instructions should include information regarding (1) the splint’s purpose, (2) the wearing schedule, (3) the splint’s care, and (4) splint precautions. The therapist should inform caregivers about whom to contact if a splint problem occurs. For example, for a client who has fluctuating edema, tone, and passive ROM, the caregiver would be instructed how to adjust the Comfy Wrist/Hand/Finger splint (Figure 15-10).

Figure 15-10 Comfy Wrist/Hand/Finger Orthosis is an example of an adjustable prefabricated splint. [Courtesy Sammons Preston Rolyan.]

The therapist gives oral and written instructions to the caregiver and demonstrates any procedure the caregiver is to perform. The therapist asks the caregiver to demonstrate the application of the splint, corrects mistakes the caregiver makes, and asks the caregiver to repeat the demonstration until it is mastered.

The therapist labels parts of the splint for easier application (e.g., right/left, thumb/wrist/forearm). When possible, photographs of proper splint position, a written wearing schedule, a list of precautions, and a splint maintenance sheet should be readily available and consistently updated.

When splinting an older adult in a long-term care facility, the therapist includes instructions in the chart to ensure staff follow-through. In addition, the therapist speaks with the immediate caregivers to determine a realistic splinting program. If an older adult is to wear a splint for a portion of the day, evening, or night shift, all staff members involved with that older adult’s care must receive instructions about the splint-wearing schedule and precautions. The splint-wearing schedule may require modification to match the staff schedule.

When appropriate, the therapist instructs caregivers about the use of inhibition techniques to facilitate proper splint application. The therapist also teaches the older adult and caregivers about the importance of intermittent passive ROM and active-assisted ROM to the immobilized joints [Dittmer et al. 1993].

Skin Care

Maintenance of skin integrity is important for older adults who need long-term splinting. The splint must be clean for application. A good cleaning method involves the use of isopropyl alcohol. Chlorine is appropriate for removal of stains. An autoclave cannot be used, and a machine is not appropriate for washing the splint. After removal of the splint, the hand requires thorough washing and drying. Stockinette worn under the splint absorbs perspiration, and powder may be helpful with moisture management.

Wearing Schedule

To determine a splint-wearing schedule, the therapist considers the goals of the splint. The purpose of the splint may be pain reduction during activity, maintenance of functional activities, prevention of skin ulceration, or prevention of a joint contracture. The goal determines whether a daytime, nighttime, or intermittent splint-wearing schedule is most beneficial. For example, an intermittent wearing schedule helps the palm or skin to dry and prevents potential skin maceration. A nighttime-wearing schedule is most appropriate if the older adult uses the extremity for functional assistance during the day.

1. What are the accommodations a therapist can make for each of the following problems: edema, ecchymosis, fragile skin, contracture, ulceration, diminished cognition, sensory loss, and motivation?

2. What are four possible goals of splinting an older adult?

3. Why are older adults prone to develop contractures?

4. What are five medical conditions more prevalent in older adults? Describe implications for splinting.

5. What are common medication side effects for three medications commonly prescribed to older adults? Describe how they could affect splinting.

6. How do instructions and selection of splint materials vary with an individual living independently in the community versus an individual in an institution?

7. What are three specific splint adaptations for older adults who have impaired cognition, sensory function, and compliance?

References

Abrams, WB, Beers, MH, Berkow, R. The Merck Manual of Geriatrics, Second Edition. West Point, PA: Merck & Co, 1995.

American Federation for Aging Research (AFAR). Prevalence of hearing loss. URL: http://www.infoaging.org/l-hear-01-loss.html 2004.

American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2002;56:609–639.

Barzel, US. Osteoporosis. In: Maddox GL, ed. The Encyclopedia of Aging. Third Edition. New York: Springer; 2001:778–780.

Beers, MH, Berkow, R. The Merck Manuel of Diagnosis and Therapy, Seventeenth Edition. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co, 1999.

Binstock, RH. Bonder BR, Wagner MB, eds. Functional Performance in Older Adults, Second Edition, Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 2001.

Blackmore, SM. Therapist’s management of ulnar nerve neuropathy at the elbow. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman AL, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:679–689.

Bland, JH, Melvin, JL, Hasson, S. Osteoarthritis. In: Melvin JL, Ferrell KM, eds. Rheumatologic Rehabilitation Series: Adult Rheumatic Diseases. Bethesda, MD: AOTA, 2000.

Bliss, MR, Bennett, GJ. Pressure sores. In: Tallis RC, Fillit HM, eds. Brocklehurst’s Textbook of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. Sixth Edition. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2003:1347–1366.

Bostrom, M. Fractures. In: Mezey MD, ed. The Encyclopedia of Older Adult Care: The Comprehensive Resource on Geriatric and Social Care. New York: Springer; 2001:272–276.

Bottomley, JM, Lewis, CB. Geriatric Rehabilitation: A Clinical Approach, Second Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2003.

Boughton, B. Osteoporosis. In: Olendorf D, Jeryan C, Boyden K, eds. The Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Research; 1999:2116–2120.

Bozentka, DJ. Pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman AL, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:1637–1645.

Cagliero, E, Apruzzese, W, Perlmutter, GS, Nathan, DM. Musculoskeletal disorders of the hand and shoulder in clients with diabetes mellitus. American Journal of Medicine. 2002;112:487–490.

Carter, SE, Campbell, EM, Sanson-Fisher, RW, Gillespie, WJ. Accidents in older people living at home: A community-based study assessing prevalence, type, location and injuries. Australian New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2000;24(6):633–636.

Chammas, M, Bousquet, P, Renard, E, Poirier, JL, Jaffiol, C, Allieu, Y. Dupuytren’s disease, carpal tunnel syndrome, trigger finger, and diabetes mellitus. The Journal of Hand Surgery (Am). 1995;20(1):109–114.

Chop, WC, Robnett, RH. Gerontology for the Health Care Professional. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1999.

Clark, CL, Wilgis, EF, Aiello, B, Eckhaus, D, Eddington, LV. Hand Rehabilitation: A Practical Guide, 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1998.

Crane, M. Preventing falls: New strategies for helping all of us stay on our feet as we age. URL: http://www.infoaging.org/feat19.html 2002.

Daleiden, S. Prevention of falling: Rehabilitative or compensatory interventions? Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation. 1990;5:44–53.

Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Profile of Older Americans. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Aging; 2003. http://www.aoa.gov/prof/Statistics/profile/2003/2003profile.pdf.

Dittmer, DK, MacArthur-Turner, DE, Jones, IC. Orthotics in stroke. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation State of the Art Review. 1993;7(1):171.

Dunlop, DD, Manheim, LM, Sohn, MW, Liu, X, Chang, RW. Incidence of functional limitation in older adults: The impact of gender, race, and chronic conditions. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2002;83:964–971.

Evans, WJ. Exercise, nutrition and healthy aging: Establishing community-based exercise programs. In: Dychtwald K, ed. Healthy Aging: Challenges and Solutions. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen; 1999:347–360.

Fess, EE, Gettle, K, Philips, CA, Janson, JR. Hand and Upper Extremity Splinting: Principles and Methods, Third Edition. St. Louis: Elsevier/Mosby, 2005.

Gillespie, LD, Gillespie, WJ, Robertson, MC, Lamb, SE, Cumming, RG, Rowe, BH. Interventions for preventing falls in older adult people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2004. [CD000342].

Good, DC, Supan, TJ. Basic principles of orthotics in neurologic disorders. In: Aisen M, ed. Orthotics in Neurological Rehabilitation. New York: Demos; 1992:1–23.

Hellmann, DB, Stone, JH. Arhritis and musculoskeletal disorders. In: Tierney LM, Jr., McPhee SJ, Papadakis MA, eds. Current Medical Diagnosis and Treatment, Forty-third Edition. New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill; 2004:778–832.

Knauf, JJ. Drugs commonly encountered in hand therapy. In: Falkenstein N, Weiss-Lessard S, eds. Hand Rehabilitation: A Quick Reference Guide and Review. St. Louis: Mosby, 1999.

Laseter, GF. Therapist’s management of distal radius fractures. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman AL, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:1136–1155.

Lavizzo-Mourey, R, Day, SC, Diserens, D, Grisso, JA. Practicing Prevention for the Elderly. St. Louis: Hanley & Belfus/Mosby, 1989.

Lewis, SC. Older Adult Care in Occupational Therapy, Second Edition. Thorofare, NJ: Slack, 2003.

Liu, W, Lipsitz, LA, Montero-Odasso, M, Bean, J, Kerrigan, DC, Collins, JJ. Noise-enhanced vibrotactile sensitivity in older adults, clients with stroke, and clients with diabetic neuropathy. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2002;83:171–176.

McFarlane, RM, MacDermid, JC. Dupuytren’s disease. In: Mackin EJ, Callahan AD, Skirven TM, Schneider LH, Osterman AL, eds. Rehabilitation of the Hand and Upper Extremity. Fifth Edition. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:971–988.

McKee, P, Rivard, A. Orthoses as enablers of occupation: Client-centered splinting for better outcomes. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2004;71:306–314.

Melvin, JL. Rheumatic Disease in the Adult and Child: Occupational Therapy and Rehabilitation, Third Edition. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis, 1989.

Merritt, JL. Advances in orthotics for the client with rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Rheumatology. 1987;14(15):62–67.

Nordell, E, Jarnlo, G, Thorngren, K. Decrease in physical function after fall-related distal forearm fracture in elderly women. Advances in Physiotherapy. 2003;5(4):146–154.

Ouellette, EA. The rheumatoid hand: Orthotics as preventative. Seminar in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1991;21:65–71.

Portnoi, V, Ramzel, P. Contractures. In: Mezey MD, ed. The Encyclopedia of Older Adult Care: The Comprehensive Resource on Geriatric and Social Care. New York: Springer; 2001:161–163.

Pincus, T. Rheumatoid arthritis. In: Wegener ST, Belza BL, Gall EP, eds. Clinical Care in the Rheumatic Diseases. Atlanta: American College of Rheumatology, 1996.

Potempa, K, Carvalho, A, Hahn, J, LeSage, J. Containing the cost of older adult falls: A risk management model. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation. 1990;6:69–78.

Redford, JB. Orthotics Etcetera, Third Edition. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1986.

Redford, JB. Orthotics and orthotic devices: General principles. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: State of the Art Reviews. 2000;14(3):381–394.

Rozmaryn, LM. The aging wrist: An orthopedic perspective. In: Lewis CB, Knortz KA, eds. Orthopedic Assessment and Treatment of the Geriatric Client. St. Louis: Mosby, 1993.

Sammons Preston Rolyan (2004) Professional Rehab Catalog. Bolingbrook, IL.

Saxon, SV, Etten, MJ. Physical Change and Aging: A Guide for the Helping Professions, Third Edition. New York: The Tiresias Press, 1994.

Skidmore-Roth, L. Mosby’s Nursing Drug Reference. St. Louis: Mosby, 1997.

Stevens, JC, Patterson, MQ. Dimensions of spatial acuity in the touch sense: Changes over the lifespan. Somatosensory and Motor Research. 1995;12(1):29–47.

Strickland, JW. Biologic basis for hand and upper extremity splinting. In Fess EE, Gettle K, Philips CA, Janson JR, eds.: Hand and Upper Extremity Splinting: Principles and Methods, Third Edition, St. Louis: Elsevier/Mosby, 2005.

Swedberg, L. Splinting the difficult hand. WFOT-Bulletin. 1997;35:15–20.

Weiss, S, LaStayo, P, Mills, A, Bramlet, D. Prospective analysis of splinting the first carpometacarpal joint: An objective, subjective, and radiographic assessment. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2000;13(3):218–226.

World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2001.