Chapter 16 Epidemiology

After reading this chapter, you will:

Introduction

Epidemiology is the study of factors affecting the health and illness of populations, and serves as the foundation and logic for interventions made in the interest of public health and preventive medicine. The constantly changing patterns of fertility and childbearing in England and Wales are monitored by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). Information on maternal, neonatal and infant mortality and morbidity is collected and published nationally by the Centre for Maternal and Child Health Enquiries (CMACE) and regionally by regional perinatal health units within the UK. This information plays an important part in future planning for health, education, social welfare and the maternity service needs within the UK.

It is from these data that trends and patterns may be identified and services planned accordingly to meet the needs of current and emerging populations. It is essential that midwives recognize processes for gathering information and utilize these data to inform their day-to-day practice.

Notification and registration of births

Under the National Health Service Act 1977, all births must be notified within 36 hours to the Director of Public Health in the area where the birth occurred. This must be carried out by the midwife or doctor in attendance at the birth, using the local notification process that may differ from area to area. Each month a list of births occurring in sub-districts is supplied to the registrar, in order to check whether every birth has been registered.

After the arrival of a new baby, it is a legal requirement to register the birth within 42 days. Registration is the responsibility of the child’s parents. If the parents fail to register the birth, the duty falls on the occupier of the premises in which the birth took place, usually the midwife or another person of authority, such as a social worker. All midwives must be fully conversant with the legal registration requirements (DPW 2008) (see website).

Facts and figures surrounding fertility and birth rates

General fertility rate

The general fertility rate (GFR) is described as the number of live births per 1000 women aged 15–44. In England and Wales, the GFR for 2007 was 62.0, an increase compared with 2006, when the GFR was 60.2 (ONS 2008a).

In 2007, there were increases in fertility rates for all age groups, except for women aged under 20, where the fertility rate fell compared with 2006. The highest percentage increase (6.0%) was observed for women aged 40 and over. For this age group, the fertility rate has risen steadily from 7.3 live births per 1000 women aged 40 and over in 1997 to 12.1 live births per 1000 in 2007. Hence, in the last decade, the number of live births to mothers aged 40 and over has nearly doubled from 12,914 in 1997 to 25,350 in 2007 (ONS 2008a).

Total fertility rate

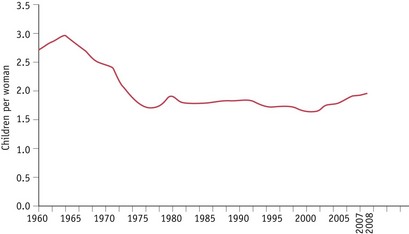

The total fertility rate (TFR) is the average number of children a group of women would have if they experienced the age-specific fertility rates of the calendar year in question throughout their childbearing lifespan. The TFR in the UK reached 1.95 children per woman in 2008 (ONS 2008b) (Fig. 16.1). UK fertility has not been this high since 1980.

The UK TFR has increased each year since 2001, when it had dropped to a record low of 1.63. The current level of fertility is relatively high compared with that seen during the 1980s and 1990s. However, the TFR was considerably higher in the 1960s, peaking at 2.95 children per woman in 1964, the height of the ‘baby boom’ (ONS 2008c). Whereas two children remains the most common family size in England and Wales, an increase in childlessness among women of childbearing age has also been noted in recent years.

Birth rate

The birth rate is the number of registered live births per 1000 population, and following a decline in the 1990s is now increasing steadily from the rate in 2002 of 11.3 to a rate of 12.8 in 2007 (ONS 2008a).

Because fertility is currently rising faster among women over 30, the average age of childbearing has continued to increase slowly. The mean age for giving birth in the UK was 29.3 years in 2007, compared with 28.6 years in 2001 (ONS 2008a). This could explain, in part, the increasing number of women seeking treatment for infertility, as general fertility decreases with age. Women of 35 are known to be on average half as fertile as those of 31 (Challoner 1999).

Teenage pregnancy rate

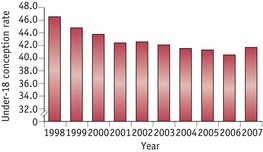

Teenage pregnancy is defined as pregnancy experienced up to and including the age of 19 years, and is frequently further divided into pregnancies up to 15 years of age, and from 15 to 19 years. In 1998, England and Wales were reported to have the highest teenage birth rate in Europe when the birth rate of women aged 15 to 19 years was 30.6 per 1000 women in that age group (UNICEF 2001). Among the developed nations, only the United States had a higher teenage birth rate of 52.1 births per 1000. In response, the British Government introduced a range of measures including the Teenage Pregnancy Strategy in 2000, with the aim of reducing the teenage pregnancy rate by half by 2010, and producing a firm downward trend in the conception rate in the under-16 years age group. Perinatal mortality and morbidity in young mothers is higher than average, so concerted attempts by Government to improve sex education and make family planning services more accessible to young people have been included in measures to attempt to reduce the teenage conception rate.

Following the introduction of these measures, the ONS figures show teenage pregnancy rates continuing to fall (Fig. 16.2) with a reduction in both the under-18 and the under-16 rates during 2006:

Fetal and infant deaths

Fetal and infant deaths are divided into defined categories. Whilst there may be similarities between these groups, it is important to look at them individually in order to identify areas for future research, and potential improvement in outcome.

Stillbirths

A baby delivered with no signs of life known to have died at 24 completed weeks of pregnancy onwards (CEMACH 2009).

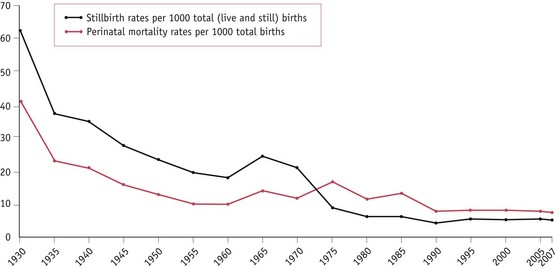

The stillbirth rate is the number of stillbirths registered during the year per 1000 registered total (live and still) births. In contrast to neonatal mortality, there has been no significant decline in the stillbirth rate since 2000. The stillbirth rate was 5.4 per 1000 total births in 2000 and 5.2 per 1000 in 2007 (Fig. 16.3). The findings from the latest CEMACH report in 2009 suggest that demographic factors known to be associated with stillbirths, such as, obesity, ethnicity, deprivation and maternal age, may be contributing to this lack of progress. In addition, over one-third (40%) of unexplained stillbirths had a birth weight below the 10th centile for gestation and a quarter (26%) of these were below the 3rd centile. This suggests that being small for gestational age may be an important contributor.

Perinatal deaths

The perinatal mortality rate comprises all stillbirths and deaths in the first week of life per 1000 registered total births. The group includes all babies who have died ‘around’ the time of birth.

The perinatal mortality rate in England and Wales fell from 19.3 per 1000 in 1975 to 7.7 in 2007 (CEMACH 2009) (Fig. 16.3). As with stillbirth, maternal age, obesity, social deprivation and ethnicity remain important risk factors for perinatal mortality.

Neonatal deaths

The neonatal mortality rate is the number of deaths of babies within 4 weeks of birth per 1000 registered live births.

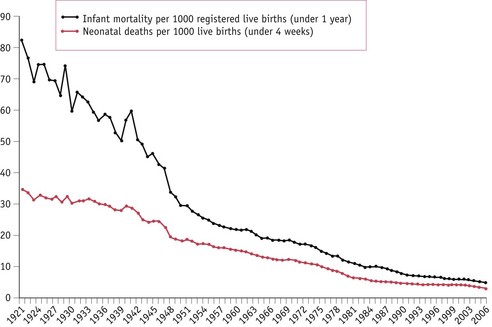

The neonatal mortality rate, like the other mortality rates, is declining in England and Wales and fell from 11.0 per 1000 livebirths in 1975 to 3.3 in 2007 (Fig. 16.4). The majority of neonatal deaths occur in the first day or two after birth, which closely relates the death of the baby to gestational age, labour and delivery.

The causes of perinatal and neonatal deaths occurring in the first week of life are obviously related and may also be responsible for later neonatal deaths; however, other factors, such as infection, may be more strongly implicated in later deaths. The reasons for reduction in the neonatal mortality rate are similar to those responsible for the decline in perinatal mortality (CEMACH 2009).

Infant mortality

The infant mortality rate is the number of deaths of infants during the first year of life (including those occurring during the first 4 weeks) per 1000 registered live births in the year.

There has been a remarkable decline in infant deaths in England and Wales, from 140 per 1000 live births in 1900 to 5.0 per 1000 in 2006 (ONS 2008d) (Fig. 16.4).

The main causes of later infant deaths include:

Reflective activity 16.1

Review your unit’s birth register and other sources of statistical information (as in the reference list).

Note the actual local rate of the following:

Have these rates changed during the last few years? If so, why do you think this has happened? How has this information been used to design services?

Predisposing causes and risk factors for fetal, perinatal and infant death

Social factors

Mortality rates for all categories of death are higher in socioeconomic groups IV and V and the gap between the social classes is widening rather than decreasing (WHO 2005). CEMACH (2009) reported that just over one-third of all stillbirths and neonatal deaths were born to mothers in the most deprived quintiles (compared with the expected 20%). Stillbirth and neonatal mortality rates for mothers resident in the most deprived areas were 1.8 times higher than for those in the least deprived area. Social class differences in access to social and medical care also continue, with women from lower socioeconomic and ethnic minority groups not fully utilizing the services available. This may partly account for the reasons why, when compared with women of white ethnicity, the ethnic-specific mortality rates showed significantly higher stillbirth, perinatal and neonatal death rates for women of black ethnicity (2.7, 2.5 and 2.2 times higher respectively) and Asian ethnicity (2.0, 2.0 and 2.0 times higher respectively) (CEMACH 2009). Low birthweight remains more prevalent in lower socioeconomic and certain ethnic groups. Even if a low birthweight baby survives the perinatal period, recent studies indicate that those who are small or disproportionate at birth, or who have altered placental growth. are at an increased risk of developing coronary heart disease, hypertension and diabetes during adult life (Godrey & Barker 1995). The perinatal mortality rate for babies of unsupported mothers is nearly double that of women who are in a supported relationship.

Biological and lifestyle factors

Characteristics such as short stature, obesity and maternal age all increase risk. CEMACH (2009) reported that mothers aged less than 20 and above 40 had the highest rates of stillbirth (5.6 and 7.7 per 1000 total births respectively), the highest rates of perinatal deaths (8.9 and 10.3 per 1000 total births respectively) and the highest rates of neonatal deaths (4.4 and 3.4 per 1000 live births respectively).

The impact of obesity on pregnancy outcomes is a growing concern internationally. CEMACH (2009) reported that of the women who had a stillbirth and a recorded body mass index (BMI), 26% (761/2924) were obese (BMI >30), and for neonatal deaths, 22% (356/1609) were obese. Unfortunately, there are no national denominator data available for obese pregnant women in the UK that would provide an estimation of this increased risk.

CEMACH reported that work has commenced on a UK project on obesity in pregnancy which will provide demographic and clinical information on a sample of women with obesity in pregnancy (CEMACH 2008).

The following are all associated with an increase in the overall risk of fetal or maternal mortality.

Teratogenic factors

Some drugs are known to have a teratogenic effect on the developing fetus, and women should be advised to inform the doctor or pharmacist of their pregnancy. Growing evidence indicates that maternal and passive smoking during pregnancy can have a direct influence on the child in utero, and it has been positively linked with prematurity, low birthweight and stillbirth. The harmful effects remain after birth and links between tobacco exposure and a subsequent increased risk of sudden infant death syndrome, and an increased tendency towards respiratory and infective illness in the child, have been reported. Regular or ‘binge’ intake of alcohol has been linked to increased risk of miscarriage, growth restriction and fetal alcohol syndrome. Drug abuse is linked to fetal abnormality, growth restriction and an increased risk of sudden infant death (see Chs 23 and 50).

Dietary deficiencies

Folic acid deficiency preconceptually and in early pregnancy has been shown to be a cause of neural tube defects (MRC Vitamin Study Research Group 1991, Smithels et al 1980, Wald & Bower 1995). Periconceptual vitamin supplementation is therefore advised, especially when there is a history of these malformations. Poor intrauterine nutrition may also affect the long-term health of the individual into adult life (Godrey & Barker 1995).

Maternal Deaths

The International Classification of Diseases, Injuries and Causes of Death (ICD9/10) defines a maternal death as:

the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and the site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from accidental or incidental causes.

The maternal mortality rate (MMR) for any year is expressed as the number of deaths attributed to pregnancy and childbearing per 1000 registered total births, or more commonly as the number of deaths per 100,000 maternities. Maternal deaths occurring more than 42 days after pregnancy or childbirth are no longer included in the figures, in line with the international definition of maternal deaths.

The World Health Organization (WHO) Safe Motherhood Initiative was launched in 1987 and maintains its aim to reduce mortality and morbidity significantly among mothers and infants. Most of the annual total of more than 500,000 maternal deaths occur in developing countries, but women still die, albeit in small numbers, in the more affluent nations of the world. There is now a global commitment to find ways to reduce the devastating numbers of maternal deaths. The United Nations Millenium Development Goal 5, Improve maternal health, has two targets – to reduce by three-quarters between 1990 and 2015 the maternal mortality ratio, and to achieve universal access to reproductive health by 2015 (UN 2008) (see Ch. 1).

In many countries of the world the maternal mortality rate is difficult to measure owing to the lack of death certificate data (should it exist at all) as well as a lack of basic denominator data, as baseline vital statistics are also not available or unreliable. The recent WHO publication Beyond the numbers; reviewing maternal deaths and disabilities to make pregnancy safer (WHO 2004) contains a more detailed examination and evaluation of the problems in both determining a baseline MMR and interpreting what it actually means in helping to address the problems facing pregnant women in most developing countries.

During the triennium 2003–05 there were 295 maternal deaths in the UK, a maternal mortality rate of 13.95 per 100,000 births (Lewis 2007). The slight increase from the maternal mortality rate of 13.07 in the previous triennia is not statistically significant. The UK maternal mortality rate showed steady decline until the mid-1980s but has since remained reasonably static. The maternal mortality rate throughout the world in 2005 is reported as 400 per 100,000 births, which ranges from 8 per 100,000 births in some developed countries to 1400 deaths per 100,000 births in Africa (UNFPA 2007) (Table 16.1).

Table 16.1 Women’s estimated lifetime risk of dying from pregnancy and childbirth

| Region | Risk of dying |

|---|---|

| Developing countries | 1 in 75 |

| Developed countries | 1 in 7300 |

| Afghanistan | 1 in 7 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 1 in 22 |

| Europe | 1 in 1400 |

| UK | 1 in 5100 |

| All world | 1 in 92 |

| Country-level differences are even more dramatic. | |

Sources: UNICEF 1996, UNFPA 2007

Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths

In the UK, a Confidential Enquiry is undertaken into every maternal death to examine factors which may have influenced the outcome, in an attempt to make recommendations and guide future practice. A Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in England and Wales report was published for each successive 3-year period from the 1952–54 report until the 1982–84 report, and since 1985, reports have included all four countries of the UK. Ascertainment has improved over the last decade as better computer software at ONS is assisting in the recognition of maternal deaths. Reporting has improved owing to the introduction of standards surrounding maternal deaths by local supervising authority (LSA) officers, so what could appear to be an increase in deaths is attributed to improved ascertainment (Lewis 2007).

Information surrounding the care of the woman is gathered by a regional coordinating body, which is then sent to obstetric and, where appropriate, midwifery and/or anaesthetic regional assessors for comment. The assessors send a completed assessment form to the Chief Medical Officer at the Department of Health. In Scotland and Northern Ireland, the system of enquiry is similar but one panel of assessors deals with all cases.

At the Department of Health, only advisors in obstetrics, gynaecology, midwifery and anaesthetics see the forms. An analysis of the cases is undertaken and recommendations are made, highlighting areas of concern and ways of seeking to ensure improvements in future years. The top ten recommendations of the 2003–05 report, which are additional to recommendations made in previous reports, are summarized in Table 16.2.

Table 16.2 Top ten recommendations – Saving Women’s Lives report 2003–05 (Lewis 2007)

| 1. Pre-conception care | Pre-conception counselling and support for women of childbearing age with pre-existing serious medical or mental health conditions which could be aggravated by pregnancy. This includes obesity. Especially relevant prior to assisted reproduction |

| 2. Access to care | Maternity services should be accessible and welcoming to all to promote easier and earlier booking. First appointment should be completed and handheld record given before 12 weeks |

| 3. Access to care | Pregnant women already 12 weeks at referral should be seen within 2 weeks |

| 4. Migrant women | Pregnant women from countries where general health may be poorer need full medical assessment and history at booking or as soon as possible. If women are from countries where genital mutilation or cutting is prevalent, this should be sensitively discussed and birth management plans agreed during pregnancy |

| 5. Systolic hypertension requires treatment | BP 160 mmHg requires antihypertensives. Consider treating at lower recordings if overall clinical picture suggests rapid deterioration is likely |

| 6. Caesarean section | For some women and babies, caesarean birth is the safest option, but women should be advised that this is not a risk-free procedure and can cause problems in current and future pregnancies. Pregnant women who have previously had caesarean birth must have placental localization in pregnancy to exclude placenta praevia/accreta |

| 7. Clinical skills | All clinical staff caring for pregnant women must be notified of and have opportunities to learn from critical events and serious untoward incidents in their area of practice |

| 8. Continuing skills training | |

| 9. Early warning scoring system | Development and routine use of national obstetric early warning chart for all obstetric women to help with timely recognition of developing critical illness |

| 10. National guidelines |

In the seventh report, Saving mothers’ lives, for the 3-year period 2003–05, maternal deaths are divided into direct deaths, which result from obstetric complications of pregnancy, labour and the puerperium, and indirect deaths, which are caused by previously existing diseases or disease that develops during or is worsened by pregnancy (Lewis 2007). Of the 295 maternal deaths assessed for this enquiry, 132 were direct deaths (a rate of 6.24 per 100,000 births) and 163 were indirect deaths (7.71 per 100,000 births). Additionally, there were 55 coincidental deaths (which are the result of causes not at all related to pregnancy, for example, road traffic accidents) and 82 late deaths in the first year after childbirth (Table 16.3).

Table 16.3 Main causes of maternal death in the UK 2003–2005 (Lewis 2007)

| Cause | No. of early deaths* | No. of late deaths** |

|---|---|---|

| Direct | ||

| Thrombosis and thromboembolism | 41 | 3 |

| Eclampsia and pre-eclampsia | 18 | 0 |

| Early pregnancy deaths (including abortions) | 14 | 0 |

| Haemorrhage (including genital tract trauma) | 17 | 0 |

| Amniotic fluid embolism | 17 | 2 |

| Genital tract sepsis (excluding abortions) | 18 | 3 |

| Anaesthesia | 6 | 0 |

| Other direct causes | 1 | 3 |

| Total Direct causes | 132 | 11 |

| Indirect | ||

| Cardiac disease | 48 | 20 |

| Psychiatric, including suicide | 18 | 18 |

| Malignancies | 10 | 27 |

| Other indirect causes | 87 | 6 |

| Total Indirect causes | 163 | 71 |

* Deaths during pregnancy and up to 42 days after end of pregnancy.

** Deaths from 42 days after end of pregnancy, up to 1 year.

In keeping with international convention, coincidental and late deaths are not included in maternal mortality statistics, but are examined in the Confidential Enquiry in case recommendations can be made for service providers.

Thrombosis and thromboembolism

This remains the commonest cause of direct maternal deaths in the UK, with 41 deaths reported in 2003–05. There were 33 deaths attributed to pulmonary embolism and the remaining 8 were caused by cerebral vein thrombosis. Additionally, three late deaths were due to pulmonary embolism (Table 16.3).

Key recommendations from the Confidential Enquiry report (Lewis 2007) were:

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists has produced guidelines for thromboprophylaxis in pregnancy and the puerperium (RCOG 2004) but the report suggests that further guidelines are needed for women with a BMI greater than 40. There is a need to raise awareness for detection of classic symptoms, especially in women perceived to be at low risk. Deaths occurred where the diagnosis had been delayed or missed, particularly within primary care or accident and emergency settings. There were also a number of women with recognized risk factors who were not offered thromboprophylaxis, emphasizing the continuing need for widespread education in this area.

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

This remains a major cause of maternal death (see Ch. 56), with 18 deaths attributed to this condition during 2003–05; the total number of deaths and mortality rate similar to the previous two triennia. Cerebral complications, mainly intracerebral haemorrhage, were the commonest cause of death. Despite recommendations made in previous reports, there were still substandard aspects of care associated with these deaths. Criticisms were made by panels of failure to react quickly enough to impending signs of eclampsia and lack of seniority and experience within teams caring for these women. There were also examples where healthcare professionals misdiagnosed and failed to make standard routine measurements of blood pressure and urinalysis. Midwives must be vigilant in their approach to early detection and management of any women presenting with risk factors and ensure appropriate management and referral.

The key recommendations (Lewis 2007) for the management of pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) include:

Haemorrhage (Chs 54 & 68)

Table 16.3 lists 14 direct deaths due to haemorrhage in 2003–05; in addition, a further 3 deaths from uterine rupture and genital tract trauma are included, which in previous triennia were reported in a separate section (Lewis 2007). The maternal mortality rate remains similar to that for 2000–02 in the UK. Haemorrhage followed caesarean section in 11 of the 14 maternal deaths. Haemorrhage remains a major cause of maternal death throughout the world, and it is estimated that a quarter of all maternal deaths are due to haemorrhage (WHO 2005).

The midwife is often the first person to see the woman who may present with acute pain or bleeding. The midwife should always refer a woman who complains of abdominal pain in early pregnancy to a doctor. Similarly, a woman presenting with pain and tender abdomen may have a concealed haemorrhage.

Postpartum haemorrhage will always remain a risk, and midwives must be trained appropriately to manage the situation whilst awaiting medical aid. The woman’s haemodynamic status should be checked in pregnancy and when anaemia is detected it should be appropriately treated. Midwives caring for women at home or in birth centres should have access to immediate resuscitation facilities until additional medical assistance can be provided.

The key recommendations made by the CEMACH report 2003–05 encompass many of these points and can be summarized as:

Genital tract sepsis (Ch. 52)

The most recent Confidential Enquiry (Lewis 2007) found there were 18 deaths in 2003–05 attributed directly to genital tract sepsis, and a further 4 deaths in which infection may have played a significant part. This represents an increase from 13 direct deaths in the 2000–02 report. Midwives must be vigilant in the detection and management of any signs of infection. The growing trend towards early discharge from hospital, especially following operative delivery, and reduced postnatal visiting may adversely influence puerperal sepsis rates. The spread of disease can be rapid and devastating; therefore, early detection and treatment are essential. Whilst numbers are small, cases of substandard care are identified throughout the last report, highlighting that care fell short of generally accepted standards.

Amniotic fluid embolism

There were 19 deaths, including two late deaths, from amniotic embolism in 2003–05 (Lewis 2007), which appears to be an increase from the two previous triennia, but this may be due to increasing efforts in the UK to correctly ascertain this difficult-to-diagnose event. The care of women suffering from this condition is the same as for any maternal collapse before, during or after labour. About 35% of the cases assessed were considered to have received suboptimal obstetric/midwifery care, but this condition carries a high mortality despite prompt treatment and good intensive care. Risk factors include higher maternal age, and, as the average age of childbearing is increasing, this may influence future statistics. Sudden collapse in labour is a common feature in this condition, which should be suspected in any woman regardless of type of labour or delivery. There is little evidence guiding practice towards prevention or treatment and further research would increase understanding and provide information on best practice in its management. A large nationwide prospective study by the United Kingdom Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS) to discern the actual incidence of amniotic fluid embolism is currently in progress.

Indirect causes of maternal death

In 2003–05, the rate for mothers’ deaths from indirect causes, such as from pre-existing or new medical or mental conditions aggravated by pregnancy (Chs 55 and 69), such as heart disease or puerperal psychosis, had not changed significantly since the previous report (Lewis 2007). Indirect causes outnumber direct causes of death in the UK, whereas worldwide they account for about 20% of maternal deaths (WHO 2005). The commonest cause of maternal death in the 2003–05 triennium was cardiac disease, with 48 deaths attributed to this cause, which has risen clearly since the late 1980s. Although these deaths are classified as indirect maternal deaths, this may change in future reports because lifestyle changes, such as the rising maternal age and obesity in the population, are increasing the incidence of cardiac complaints in the childbearing population generally.

The number of deaths from suicide (Ch. 69), the most common single cause of maternal death in the 2000–02 report (58 deaths), decreased to 37 in 2003–05. This decrease probably indicates that previous recommendations to identify women at risk and offer specialized support services in the antenatal period have been heeded. Most suicides were late deaths, occurring more than 42 days but less than one completed year after the end of the pregnancy.

It has been recognized for some time that the underlying root causes of maternal mortality are often social or other non-medical reasons. As with previous UK Confidential Enquiry reports, analysis of the data for 2003–05 reveals that women were more likely to die during pregnancy or childbirth if they were from the most disadvantaged groups in society – socially excluded, lower socioeconomic groups, the very young, and women from certain ethnic communities. It is also clear that vulnerable women with complex social requirements most need care in pregnancy but are least likely to access and maintain contact with maternity services.

Midwives should ensure that services are planned to meet the needs of the most vulnerable women in our society. There should be safeguards built into monitoring systems to ensure that women shown to be at higher risk do not ‘slip through the net’ (DH 2007).

Midwives should be aware of their professional accountability when caring for women with psychiatric and psychological problems during pregnancy and the puerperium. They should be vigilant in identifying women at risk, and have access to appropriate sources of referral should problems arise. Working within the remit of their professional boundaries, it is essential for midwives to have access to appropriate mental health practitioners at all times.

Statistics influencing change: reducing maternal, fetal and perinatal mortality

There are marked geographical differences in mortality rates. Improvements will occur when efforts to improve the whole aspect of the nation’s health, through changes in healthcare provision, housing, education, employment prospects and general social welfare, are effective. The detrimental effects of socioeconomic deprivation are recognized universally (DH 2005). Midwives need to influence policy at local, regional and national levels to encourage investment in maternal and child health services.

One of the major influences in the reduction of infant mortality in the last decade has been the reduction in deaths attributed to sudden infant death syndrome (Ch. 50). The ‘reducing the risk’ information leaflet (DH 2001) is widely distributed to all expectant and new mothers. The Care of the Next Infant (CONI) scheme provides support and resources to families where there is an increased risk of cot death.

Midwives must be aware of their responsibilities in child protection issues, and appropriate training in managing these issues should be widely encouraged. Many families are living in extremely difficult conditions and stress levels are high. There is a growing awareness of the condition ‘shaken baby syndrome’, illustrated by highly publicized cases where babies, originally thought to have died from cot death syndrome, have been rediagnosed as having been victims of child abuse. Scarce resources should be appropriately targeted to ensure that those families in need of extra support are detected and receive the help that they need. This includes referral to voluntary sector services and agencies, such as the NSPCC, which provide positive parenting support. Parenting skills are highlighted as an important theme within education. Midwives can support this initiative and local schemes by visiting the schools and contributing to the programme. The detrimental effect of domestic violence within families on maternal and infant welfare is also well known. Services must be designed to recognize and support women who are victims of domestic violence (DH 2000, Lewis 2007, RCM 1997).

Reflective activity 16.2

What measures are being taken in your area to address the effects of social exclusion and poverty, to ensure that all women have equitable access to care in pregnancy?

There is a growing concern not only about mortality, but also about the quality of life of the survivors. Some babies who survive perinatal complications may be left with a permanent handicap, therefore there is emphasis to measure morbidity, with many regions producing data that relate to outcomes of all babies born below a certain birthweight. The EPICURE study (Wood et al 2000) focuses particularly on the mortality and morbidity of babies born between 24 and 26 weeks’ gestation and will provide important information to those planning ongoing services for these children.

Collection of statistics is meaningless unless the information gathered is put to good use.

Being aware of how local, regional and national statistics can be used in the provision and development of services, midwives may contribute to ways of improving clinical practice. They may also contribute to bids for service innovations in all areas, particularly those aimed at reducing inequalities.

Key Points

Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). Perinatal mortality 2006: England, Wales and Northern Ireland. London: CEMACH; 2008.

Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). Perinatal mortality 2007: United Kingdom. London: CEMACH; 2009.

Challoner J. The baby makers: the history of artificial conception. London: Macmillan; 1999.

Department of Children, Schools and Families (DCSF). Every child matters: teenage pregnancy (website). www.everychildmatters.gov.uk/teenagepregnancy, 2009. Accessed March 2009

Department of Health (DH). Domestic violence: a resource manual for health care professionals. London: DH; 2000.

Department of Health (DH). Reduce the risk of cot death: an easy guide. London: DH; 2001.

Department of Health (DH). Tackling health inequalities: status report on the programme for action (website). www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4117696, 2005. Accessed September 2008

Department of Health (DH). Maternity matters: choice, access and continuity of care in a safe service (website). www.dh.gov.uk, 2007. Accessed December 2008

Department for Work and Pensions (DPW). Joint birth registration recording responsibility (website). www.dwp.gov.uk/publications/dwp/2008/birth_registration_ia.pdf, 2008. Accessed September 2008

Godrey KM, Barker DJP. Maternal nutrition in relation to fetal and placental growth. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 1995;61(1):15-22.

Lewis G, editor. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). Saving mothers’ lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer – 2003–2005. The seventh report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. London: CEMACH, 2007.

MRC Vitamin Study Research Group. Prevention of neural tube defects: results of the Medical Research Council Vitamin Study. Lancet. 1991;338(8760):132-137.

Office for National Statistics (ONS). Birth statistics: births and patterns of family building England and Wales (FMI) No. 36 – 2007 (website). www.statistics.gov.uk/downloads/theme_population/FM1_36/FM1-No36.pdf, 2008. Accessed July 2009

Office for National Statistics (ONS). Births and deaths in England and Wales 2008 (website). www.statistics.gov.uk/pdfdir/bdths0509.pdf, 2008. Accessed August 2009

Office for National Statistics (ONS). Key population and vital statistics 2006. Series VS No 33 PPI No 29. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Office for National Statistics (ONS). Mortality statistics: childhood, infant and perinatal: review of the National Statistician on deaths in England and Wales, 2006, Series DH3 No 39 (website). www.statistics.gov.uk/downloads/theme_health/DH3_39_2006/, 2008. Accessed March 2009

Royal College of Midwives (RCM). Domestic abuse in pregnancy. Position Paper 19. London: RCM, 1997.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG). Thromboprophylaxis during pregnancy, labour and after normal vaginal delivery. Guideline No 37 (website). www.rcog.org.uk, 2004. Accessed November 2008

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG). Registration of stillbirths and certification for pregnancy loss before 24 weeks of gestation (Good Practice No 4). RCOG London: RCOG; 2005.

Smithels RW, Sheppard S, Schorah LJ, et al. Possible prevention of neural tube defects by periconceptual vitamin supplementation. The Lancet. 1980;1(8164):339-340.

UN. United Nations Millennium Development Goals (website). www.un.org/millenniumgoals/, 2008. Accessed January 2009

UNFPA. Maternal mortality in 2005. A joint report by UNFPA, WHO, UNICEF and The World Bank (website). www.unfpa.org/mothers/statistics.htm, 2007. Accessed November 2008

UNICEF. Estimates of maternal mortality (website). www.unicef.org/pon97/p48b.htm, 1996. Accessed November 2008

UNICEF. A league table of teenage births in rich nations (website). www.unicef-irc.org, 2001. Accessed October 2008

Wald NJ, Bower C. Folic acid and the prevention of neural tube defects. British Medical Journal. 1995;310(6986):1019-1020.

World Health Organization (WHO). Beyond the numbers. Reviewing maternal deaths and complications to make pregnancy safer (website). www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/btn/text.pdf, 2004. Accessed March 6, 2009

World Health Organization (WHO). The World Health report: make every mother and child count. Geneva: WHO; 2005.

Wood NS, Marlow N, Costeloe K, et al. Neurologic and developmental disability after extremely preterm birth. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;343(6):378-384.