Chapter 58 Abnormalities of the genital tract

Introduction

The true incidence of reproductive tract anomalies is uncertain and their role in reproductive difficulties is unclear (Saravelos et al 2008, Shulman 2008). While structural abnormalities of the uterus are particularly likely to cause problems, pregnancy and labour may also be affected by other conditions such as fibroids or uterine displacements. Female genital mutilation (also known as female circumcision) presents clear health risks for mother and baby. The midwife must be able to give appropriate and safe care for any woman presenting with a genital tract anomaly.

Developmental anomalies

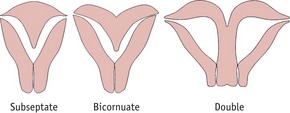

Most of the female genital tract arises from the müllerian ducts (see Ch. 29), which form during embryonic life and which fuse by the 12th week after fertilization. The median septum then breaks down, thus forming a single uterus (Laufer et al 2005). Should this process fail, abnormalities such as double uterus (with or without a double cervix and vagina), bicornuate uterus or subseptate uterus will occur (Fig. 58.1). As the müllerian ducts and wolffian ducts (see Ch. 29) develop close together, genital tract anomalies may be accompanied by malformations of the kidney and ureters. Care should include assessment of the urinary system (Laufer et al 2005).

Diethylstilbestrol (DES)

This synthetic non-steroidal oestrogen was used for approximately 30 years to treat conditions such as recurrent pregnancy loss and threatened abortion. It is still sometimes used as a form of postcoital contraception (Mackay Hart & Norman 2008). Girls who have been exposed to DES in utero have an unusually high incidence of uncommon anomalies. These include an increased incidence of:

Reproductive function is impaired. Conception may be difficult; ectopic pregnancy and preterm birth are commoner (RCOG 2002).

Unicornuate uterus

This uncommon abnormality arises from failure of development of one of the müllerian ducts. There is a higher rate of spontaneous abortion, breech presentation, fetal growth restriction and preterm labour, possibly due to the limited space in the uterine cavity (Akar et al 2005). Caesarean delivery is therefore more likely. If the pregnancy develops in a rudimentary horn, the outcome is usually spontaneous abortion or occasionally rupture of the rudimentary horn, as the myometrium becomes rapidly stretched.

Double uterus (uterus didelphys)

This may be accompanied by a double vagina or a longitudinal vaginal septum. As the pregnancy progresses, the midwife will notice that the fundus is abnormal in shape and may feel unusually wide. Breech presentation is common. As the pregnancy continues, the non-pregnant uterus will enlarge under the influence of the pregnancy hormones and may occupy space in the pelvis, thus obstructing labour. Twin pregnancy (one fetus in each horn) has been recorded (Ahmad et al 2000).

Subseptate and bicornuate uterus

This occurs when complete obliteration of the müllerian septum fails. A subseptate uterus is outwardly normal, but the midwife may recognize a bicornuate uterus, which has a wide, heart-shaped fundus. This can be detected on abdominal examination and may be visible under the abdominal wall in a slim woman, especially after the third stage of labour. These anomalies do not usually cause difficulties in conception or in early pregnancy. However, they are associated with transverse lie and breech presentation, as the abnormal uterine structure hinders the normal process of spontaneous version between 30 and 34 weeks’ gestation. Attempts at external cephalic version of the fetus will be unsuccessful.

The midwife should consider the possibility of structural abnormality of the uterus in any woman with a history of recurrent malpresentation. The progress of the first and second stage of labour is usually normal where there is a subseptate or bicornuate uterus. However, retained placenta may occur in the third stage.

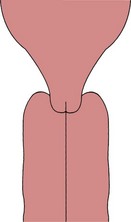

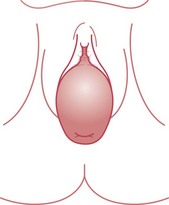

Vaginal septum

A vaginal septum (Fig. 58.2) may be longitudinal or transverse, complete or partial. It may be detected on vaginal examination, but, as the tissue is usually soft and is easily deflected by the examining fingers, the diagnosis is often overlooked. A vaginal septum may obstruct fetal descent during labour (Heinonen 2000).

Associated problems

The presence of a uterine malformation is associated with an increased risk of recurrent spontaneous miscarriage and preterm birth (Mackay Hart & Norman 2008, Woelfer et al 2001).

The midwife should refer the woman to an obstetrician so that appropriate care may be planned as there is a higher likelihood of the need for intervention during labour.

Displacements of the uterus

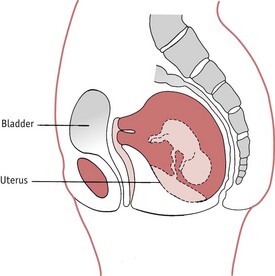

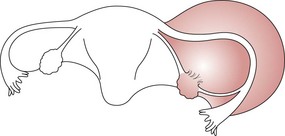

Retroversion of the gravid uterus

Retroversion of the uterus, where the pregnant uterus falls back into the hollow of the sacrum (Fig. 58.3), is normally of little clinical significance (Mackay Hart & Norman 2008). During pregnancy, the condition usually resolves spontaneously as the uterus grows and rises into the abdomen around the 12th week (Mukhopadhyay & Arulkumaran 2004).

However, rarely, the retroversion fails to resolve and the uterus becomes fixed or incarcerated in the pelvis. Between the 12th and 16th week of pregnancy the retroverted pregnant uterus fills the pelvis and the cervix is drawn up towards the pelvic brim. The anterior vaginal wall and the urethra become stretched, the urethra narrows and the mother is unable to pass urine.

Diagnosis

The woman will initially complain of pelvic pressure and difficulty in micturition and later of complete inability to pass urine. The bladder becomes more distended and, if unrelieved, overflow incontinence will occur.

The woman will experience severe abdominal pain. On abdominal examination there is a soft swelling (the bladder) above the pubes, which may extend to the umbilicus and may be mistaken for the uterus. The fundus is not palpable at the brim of the pelvis. A pelvic ultrasound scan will assist the diagnosis (Mukhopadhyay & Arulkumaran 2004).

Treatment

The bladder is emptied with an indwelling catheter and is then kept empty until bladder tone returns. Once the bladder is empty, the uterus usually corrects its malposition spontaneously. This may be assisted if the mother lies in the semi-prone or Sims position (see Ch. 61). The retroversion will not recur, since the uterus will, in a few days, be too big to fall back into the pelvis. Persistent retroversion has been reported but is rare (Hamoda et al 2002).

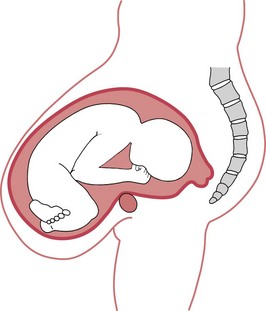

Anteversion of the gravid uterus (pendulous abdomen)

This rare condition (Fig. 58.4) may occur in multiparous women whose abdominal muscles have been weakened by repeated pregnancies or those who have a midline abdominal wall hernia, possibly associated with an old scar (Saha et al 2006). Separation of the rectus abdominis muscle allows the uterus to fall forward and in extreme cases the fundus may lie below the symphysis pubis. As the uterus becomes heavier, the woman experiences backache and abdominal pain. The presenting part will not engage and dystocia is likely because the long axis of the uterus is at an angle to the pelvic brim. An abdominal binder may bring relief (Saha et al 2006). This should be worn during labour to facilitate engagement and descent of the fetus. The ‘all-fours’ delivery position should be avoided.

Prolapse of the gravid uterus

Uterine prolapse is rare in pregnancy (Fig. 58.5). Laxness of the uterovaginal supports allows the uterus to descend so that the cervix is found at or just behind the vaginal introitus. The condition is most troublesome in the first trimester of pregnancy as the uterus increases in size and weight and the ligaments soften and relax. A ring pessary may relieve the prolapse. As the uterus grows into the abdomen, the condition improves, although it may recur in late pregnancy. Caesarean section may be recommended to prevent further damage to the uterovaginal supports (Mukhopadhyay & Arulkumaran 2004).

Pelvic masses

Fibromyomata (fibroids)

Fibroids are the commonest pelvic tumours, occurring in up to 30% of women of childbearing age (Cooper & Okolo 2005). They are commoner in older women and in young West Indian and West African women. The presence of fibroids (leiomyomas) increases the risk of complications such as threatened abortion, antepartum haemorrhage, breech presentation and caesarean birth (Mukhopadhyay & Arulkumaran 2004).

On uterine palpation, one or more swellings may be felt, continuous with the uterine wall (Fig. 58.6). A large fibroid may be mistaken for the fetal head. In pregnancy, hypertrophy of the myometrial fibres and increased vascularity and oedema cause the fibroid to enlarge and soften.

Red degeneration of a fibroid (see website) may cause acute pain and vomiting in pregnancy and torsion of a pedunculated fibroid (see website) may require myomectomy (Cunningham et al 2005). Most fibroids are found in the body of the uterus and do not affect the course of labour. Rarely, one may occur in the lower segment beneath the presenting part. This will prevent fetal descent into the pelvis and may obstruct labour. During the third stage of labour, postpartum haemorrhage may occur (Mukhopadhyay & Arulkumaran 2004).

Pregnancy complicated by fibroids is considered high risk and the labour and birth should take place in hospital in case difficulty should arise. During the puerperium, fibroids regress and become smaller as autolysis reduces the myometrial mass (Mukhopadhyay & Arulkumaran 2004).

The midwife should be aware of any woman who has a history of treatment for fibroids prior to pregnancy. Myomectomy involves incisions on the uterus and this may pose a risk of scar rupture in future pregnancy (Hockstein 2000). Selective embolization of fibroids is often the preferred treatment and the risks to future fertility are believed to be small (McLucas et al 2001).

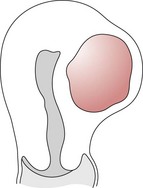

Ovarian cyst

Sonographically detectable adnexal masses occur in up to 6% of fertile women (Bayar et al 2005). Corpus luteum cysts are common in the first trimester and usually regress spontaneously. A 12-year retrospective study found a 13% malignancy rate in ovarian cysts (Sherard et al 2003).

The cyst may be in the abdomen or in the pelvis (Fig. 58.7). There is a risk of malignancy or torsion, the risk of malignancy rising with increasing age. Torsion is most likely during the second trimester or in the puerperium (Mukhopadhyay & Arulkumaran 2004). Simple non-malignant cysts can be successfully aspirated during pregnancy, although conservative management is also an option (Caspi et al 2000, Zanetta et al 2003).

Female genital mutilation (female genital cutting, female circumcision)

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is the removal of all or part of the external female genitalia for non-medical reasons (WHO 2008). The custom still persists among some groups, particularly those from Nigeria, Ethiopia, the Sudan and Egypt. It is a cultural requirement and may be a rite of passage into adult status within the community. It is usually performed before the age of 15 (WHO 2008).

The World Health Organization (2008) classifies FGM as follows:

Female genital mutilation is illegal in the UK and many other countries and is considered to be a violation of human rights (WHO 2008). It carries a significant immediate mortality from haemorrhage and sepsis. Lifelong morbidity from urinary infection, pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis and renal damage may follow.

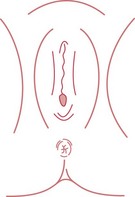

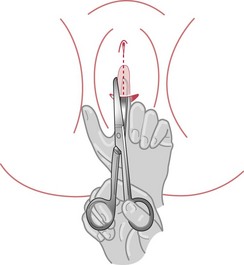

Infibulation presents particular problems in childbearing. In pregnancy, urinary tract infection is more likely. The rates of caesarean section, postpartum haemorrhage and perinatal death are increased in women who have undergone FGM (WHO 2006). When attending the woman in childbirth, the midwife must be prepared to perform an anterior episiotomy, separating the labial remnants (Fig. 58.10), and the perineum must be meticulously repaired. Repair of the labia in such a way as to restore the infibulated state is illegal (RCOG 2003).

If the infant is a girl, the midwife must be aware that the family may wish to have the child circumcised. Under the terms of the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2004 it is now illegal to have this carried out abroad under the principle of ‘extra-territoriality’ (see website) (Kwateng-Kluvitse 2005). Midwives should initiate their local Child Protection process if they feel that a female child is at risk.

At booking, the midwife should ascertain whether the woman has undergone genital mutilation. The words used should reflect the midwife’s attitude and approach, which must be well informed, non-judgmental and sensitive. Good communication is essential. If the woman and the midwife do not speak the same language, an interpreter must be found – this should not be a family member. A careful history must be taken; details of any previous births must be recorded, including any surgical interventions required, the condition of the infant and the woman’s health since the birth. A physical examination should be carried out, with consent. Minor degrees of genital mutilation will probably require no special attention, apart from ascertaining the woman’s wishes regarding her labour and delivery care.

Infibulation, however, may present problems. Detailed information about previous pregnancies and births will help to inform the current management. The woman’s beliefs and knowledge about the impact of her surgery on childbirth must be assessed. Her wishes for this pregnancy and birth should be discussed, but the midwife must make it clear that re-infibulation following the birth is not permitted by law. The possibility of the need for episiotomy should be raised. Advice regarding hygiene in pregnancy is essential, especially the need to reduce the risk of urinary tract infection.

De-infibulation services should be available to women who request it. Ideally, this procedure should be performed before pregnancy, or around 20 weeks’ gestation (RCOG 2003). The midwife should refer the woman to an obstetrician. In all her communication, the midwife must be aware of the social implications of her advice and actions.

The Foundation for Women’s Health, Research and Development (FORWARD) website contains information on FGM, including potential sequelae such as obstetric fistula formation.

Conclusion: implications of genital tract anomalies for midwifery practice

The true incidence of genital tract anomaly is unknown. The diagnosis may be made only following investigations for reproductive problems, such as recurrent pregnancy loss, pain or infertility.

A thorough but tactful history must be taken, with attention to privacy during the consultation. The midwife should assess the woman’s general health and enquire about the information and advice which may have been given by other health professionals. Lower abdominal or periumbilical scars suggest gynaecological surgery and the midwife should enquire about the procedure. If there is a history of reproductive problems or gynaecological surgery, the woman should be referred to an obstetrician for an opinion on management of the pregnancy and labour.

Psychological support is essential. The midwife must be sensitive in ascertaining the history and giving advice and care during pregnancy. Working in partnership with the woman may ameliorate some of the psychological impact by focusing on normality, as far as is compatible with safety. Anxiety may be reduced and feelings of control and satisfaction enhanced if the woman is an informed and equal partner.

The midwife may be the first healthcare practitioner that the woman comes into contact with, and may pave the way not just for this pregnancy, but for interactions with other practitioners within the health services. A sensitive, respectful and caring approach ensures that the woman’s experience of healthcare is positive, and will also contribute to the health of the woman, her baby and family.