Chapter 4 The midwife as a lifelong learner

After reading this chapter, you will:

Introduction

One of the strengths of UK midwifery has been that midwives have had control of their education. This chapter includes an overview of the recent history of midwifery education, in the context of some of the policy and practice issues which have shaped and influenced the provision of pre- and post-registration education in the UK. To understand midwifery education in the UK now, and to think about the future direction it will take, it is helpful to appreciate some of the influencing factors and history of midwifery. Education and learning will also be explored in a broader sense, and how both may be utilized by midwives in their present and future practice.

Lifelong learning

Lifelong learning is about holding a view that the pre-registration education is a springboard for future practice with the clinical area a place of learning and development (see website). This approach encourages a dynamic and enriching process, for midwives to think and reflect on their practice, to learn from each experience, refining and improving their knowledge and skills and imparting this philosophy to their clients and students. This creative and positive approach, where the health service is a learning organization, able to learn and develop from positive events and mistakes, can provide a high quality of service to women and their babies.

In reality, this must be more than ‘paying lip service’. The pace of change and of the development of knowledge means that midwives must continually be updating their knowledge and skills in order to provide a safe and effective level of care.

Midwifery education

Midwifery traditionally emerged from an apprenticeship model of education (Leap & Hunter 1993). Generally, women had personal experience of pregnancy and childbirth and would literally ‘learn by Nellie’ by accompanying a midwife in her daily work. The ‘education’ of midwives was, therefore, variable as regards the quality of experience to which a learner midwife could be exposed, and limited by the difficulty of accessing scientific information which would have been available to their male counterparts (Donnison 1988 and Ch. 2). Education and practice reflected the society of the time, often guided by superstition, custom and practice.

Many years of campaigning by the Midwives Institute (later to become the Royal College of Midwives) and its redoubtable members, including Rosalind Paget and Louisa Hubbard, supported by a small number of powerful politicians, achieved the Midwives Act of 1902. The primary purpose of the legislation was to safeguard the public from the practices of uneducated and untrained women, who assisted those who were too poor to pay for medical care during childbirth. Midwives were amongst the first to achieve professional regulation and were set on the pathway to standardized education, training and practice. Other parts of the UK attained registration of midwifery practice at a later date: Scotland in 1915 and Ireland in 1918. The Nurses Registration Act (1919), set up the General Nursing Council, brought nursing training and standards along similar lines to those of midwives.

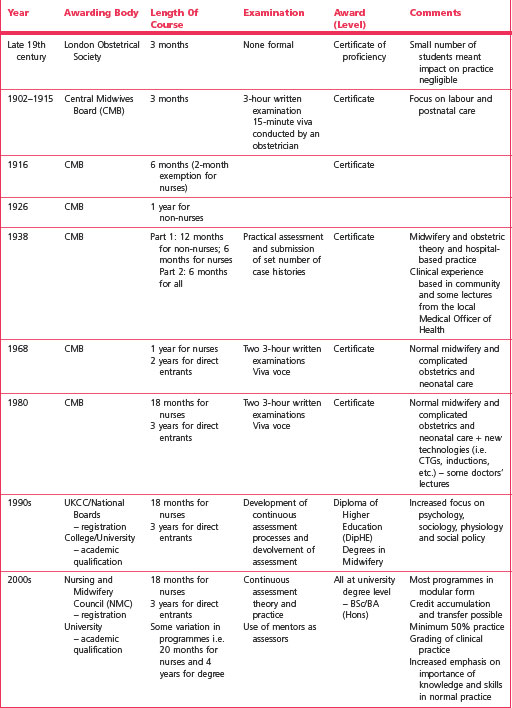

The Central Midwives’ Board (CMB), established by the 1902 Act, was charged by Government with responsibility for training midwives and conducting their examinations. The educational programmes developed accordingly, as shown in Table 4.1 and Figure 4.1.

By the late 1980s, there was increasing concern within the profession about both the direction midwifery education was taking and reduced recruitment into the profession. By 1988, only one school in England provided a ‘direct entry’ programme, though it was believed that this route could be more cost-effective and a more health-focused way of training midwives.

Acting on the findings of an ENB/DH-funded study (Radford & Thompson 1988), the Department of Health supported seven pilot schools to develop direct entry programmes, generally at DipHE level, linked to higher education institutions (HEIs). The success of these programmes was such that by 2000, three-quarters of midwives qualifying had been trained through the direct entry route (UKCC 1999). Though there is some debate about whether the shortened course for nurses should be retained, this route is still supported by midwives, and its retention recommended by the UKCC Commission for Education (1999) and currently by commissioners (see website).

Moving into higher education

The last 30 years have been a time of tremendous change, from a scenario where midwifery education was provided locally, managed by the head of midwifery in the hospital, funded from the maternity care budget, to being absorbed into schools of nursing and midwifery, then colleges of health and/or nursing, and the final move into universities, with more complex funding streams controlled through strategic health authorities.

Project 2000 (UKCC 1986) recommended that nursing and midwifery education have an 18-month shared core, followed by an 18-month ‘branch’ in midwifery, children’s nursing, mental health, acute care or learning disabilities; that students be supernumerary, and courses be offered in higher education (HE) at diploma or degree level. Midwives overwhelmingly rejected this model for midwifery education, choosing to retain the direct entry route or 18-month programme, generally keeping control over their curriculum, though midwifery education moved, like nursing, into higher education. It is possible that this rejection avoided some of the problems experienced in nursing as described in the Peach Report (UKCC Commission for Education 1999).

It has been suggested that the move into higher education, which coincided with Project 2000 development, impacted on the student experience and the development of clinical expertise and confidence. Contributory factors were larger class sizes and geographical move from hospitals and clinical areas (Bower 2002). Though some midwives worked closely with their nursing colleagues to the extent of sharing elements of their programmes, others retained their midwifery identity, preferring to develop shared learning between the direct entry and 18-month route (Eraut et al 1995).

The RCM Education Strategy (RCM 2003) highlighted actions to redress the balance and align education more closely with clinical practice. Some recommendations, such as the development of a national midwifery curriculum, are straightforward, especially given the development of a national curriculum in children’s education. Others, including the recommendation that students undertake at least five home births, two births within a birth centre setting, complete at least two experiences of physiological third stage, and have experience in a variety of settings, are more challenging. Utilizing the strategy could assist students and midwives to move clinical practice towards normality and community settings.

This strategy also recommends that educationalists spend a minimum of 20% of their time within the clinical area; that clinical managers seek to find a space for educators, and work to mitigate negative effects of geographical separation. Presently, the MINT project is exploring the clinical role of the midwife teacher (see website).

There may be midwives who seek the academic ivory towers, but there are also a significant number of midwives locked in the turret!

(RCM 2003:9)

Regional shortages of midwives mirror a corresponding shortage of educationalists. The proliferation of different roles, such as practice facilitator, clinical facilitator and practice development midwives, may, in part, replace the traditional role of the midwife teacher, but removes a potentially valuable resource from students and qualified staff. Midwifery teachers are usually highly experienced in clinical practice and thoroughly grounded in the theory of advanced midwifery, enhanced by a knowledge of the principles and practice of the education of adults. This level of knowledge and skills is a significant investment, and makes the educationalist a useful member of the maternity services, if fully involved and utilized.

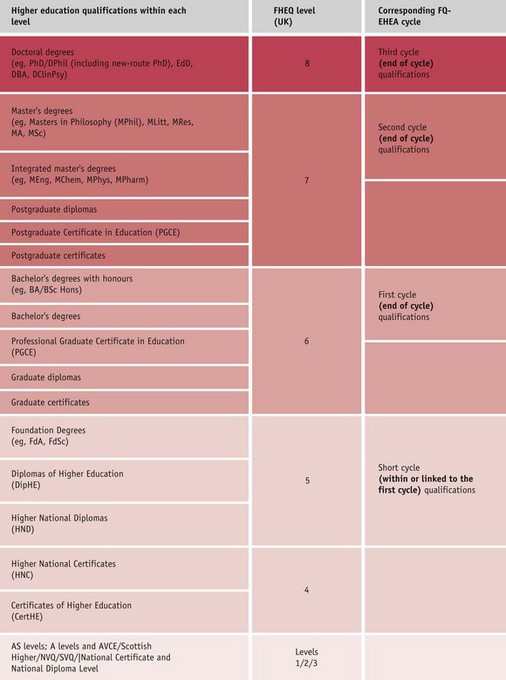

Diplomas, degrees and scholarship

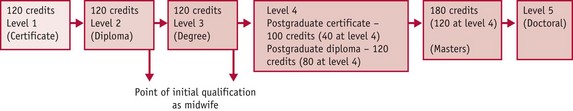

Two programmes are available to the person wishing to enter midwifery in the UK: either a 3-year direct entry programme, or an 18-month shortened programme for those who have completed nursing. Both are at degree level. Figure 4.2 illustrates the educational system in the UK.

Figure 4.2 Typical higher education qualifications at each level of the frameworks for higher education qualifications (FHEQ) and the corresponding cycle of the Framework for Qualifications of the European Higher Education Area (FQ-EHEA). For more information, see website.

(Adapted from The framework for higher education qualifications in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, August 2008. © The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education, 2008. www.qaa.ac.uk. Reproduced with permission.)

Courses are designed around the key competencies and clinical experience as laid down by the EC Midwives Directives (EC 1983, 2005) and Nursing and Midwifery proficiencies (NMC 2009). Clinical practice is a crucial part of the programme, and includes students working a variety of shifts (including weekends). Courses include ‘self-directed study time’, and a variety of different learning and teaching methods to enhance learning. Students are often mature people, sometimes on their second or third career, and possibly the family breadwinner; with different stressors from those of traditional university students.

There is a debate about whether qualifications make the practitioner a better midwife (Bower 2002). Research into nursing graduate practitioners demonstrated that 6 months after qualification, given appropriate support, practitioners had reached a similar point to those who had followed a less academic path. Graduate practitioners tend to remain in practice (Bircumshaw & Chapman 1988); demonstrate the ability to problem-solve and have a similar level of competence to their diplomate colleagues (Bartlett et al 2000, While et al 1998); and are more likely to be motivated to undertake continuing professional education (CPE) than are diplomates (Dolphin 1983).

As a graduate profession, practitioners should be equipped with analytical thinking and reflective skills, supporting practical skills. Though the academic requirements may discourage some people from pursuing midwifery, strategies are in place to provide additional academic and pastoral support for people with non traditional qualifications.

Practitioners who have completed midwifery programmes in the past, or who have completed a diploma, can apply to ‘top up’ to BSc (Hons) level. Most universities stipulate a total of 360 credits to gain an honours degree – usually consisting of 120 credits at each of levels 1, 2 and 3 (Fig. 4.3).

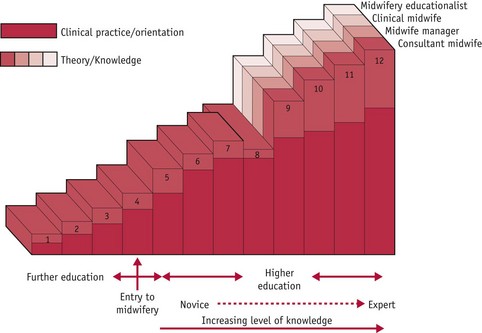

The RCM strategy (2003) proposed a continuum of midwifery, from a ‘pre-midwifery’ programme, through pre-registration training, to the different pathways of consultant midwife, educationalist or manager, always with a firm foundation of clinical practice. The process of moving along the continuum of midwifery illustrates that practitioners often start at different points and have enormous potential for professional and personal growth, and reiterates the commitment to continuing professional education (see Fig. 4.4).

Continuing professional development/education (CPD/E) forms a crucial and enduring part of the midwife’s role, and has been part of midwifery practice since the 1936 Midwives Act, requiring midwives to undertake periodic refreshment in order to be able to continue practising. The Post-Registration Education and Practice (PREP) Project (UKCC 1990) brought these principles to nursing and health visiting, requiring practitioners to complete 5 days every 3 years with a professional portfolio illustrating self-assessment, development plan and reflective activities.

The PREP standard presently requires that practitioners complete a minimum of 450 hours of practice and 35 hours of study during the 3 years prior to renewal of registration, and those holding dual qualifications must demonstrate 900 hours of practice in nursing and midwifery (NMC 2008).

‘PREP’, portfolios and practice

Nurses and midwives are required as part of their PREP requirements to maintain a personal profile. The purpose of this is to record their learning activity for re-registration purposes. A profile is a personal document. It does not belong to the NMC or to the nurse or midwife’s employer (NMC 2008).

The PREP (NMC 2008) requirement to keep a professional ‘profile’ (or portfolio) has resulted in structured approaches to recording learning and development. It is important to consider the ‘shape’ of the portfolio – moving from a view of a portfolio as a collection of certificates from different study days to a more dynamic tool allowing the practitioner to record activities, reflect on practice, and consider learning and development in the past, present and future, as a development plan. The latter approach includes a curriculum vitae (CV), and, indeed, one way of seeing the portfolio is to think of it as a dynamic CV.

There are several guidance publications available to guide portfolio development (NMC 2008, RCM 2000). The practitioner can choose to use a commercially produced portfolio, loose-leaf binder, computer, or even a personal digital assistant (PDA) unit to record learning and experience (Fig. 4.5) (see website).

Updating can include study days, conferences, working in different practice areas, or private study, such as undertaking a literature review. The important element is identifying the learning resulting from the activity, maximizing its effect.

If a literature search or reading activity is used as an updating activity, rigour needs to be used to ensure that the work is focused and applied to the individual’s practice. This makes active reading critical (see website).

Reflective activity 4.1

After your next study day, spend some time afterwards thinking about it. What were the key elements of the day? Were there any keynote speakers who had an impact on you? Did you learn anything new? If not, why not? Write this down – perhaps using the framework in Box 4.1. Record at least one thing that you learned that you could bring into practice.

Future developments: degrees, masters and PhDs/APEL/APL

A plethora of choice exists for midwives wishing to develop their knowledge and skills. A decade ago, diplomas were the highest qualification available for the majority of practitioners, and a midwife wanting a Masters degree had to settle for a Masters in Social Science, Psychology, Nursing or Education. Now, most universities offer degree studies from Bachelors to Masters level studies in Midwifery Studies or Science.

A growing number of midwives are undertaking doctoral studies (PhD) and/or clinical doctorates (DClinPrac). Figure 4.2 illustrates the academic hierarchy, with the Master in Philosophy (MPhil) and PhD considered the pinnacle of study, requiring the practitioner to learn the knowledge and skills of research, and then apply them to a research project. As the number of midwives holding these higher degrees grows, the status of, and internal belief in, midwifery will increase, though it will be important to ensure that at the heart of what is studied is knowledge pertinent and applicable to midwives, midwifery, and, above all, to women and their babies.

Work-based learning (WBL) may include elements of accreditation of prior learning (APL) or accreditation of prior experiential learning (APEL). This can involve guided study within the clinical area, practical sessions or activity. Some programmes include work-based learning to denote the practical part of the course, either self-assessed or under the supervision of the course tutor or suitably qualified colleagues. Students are provided with a workbook or logbook, and this forms part of the reflection and recording necessary for demonstrating their progress.

WBL is sometimes viewed as a way of providing practitioners with learning experience, without ‘losing them’ while they go elsewhere for study. It enables learning to be applied and placed firmly within the practitioner’s own workplace, and can contribute to the concept of the learning organization (ENB 1995). A learning organization is a dynamic one that can adapt and change as required, and which enables its workers to participate at all levels in the organization (ENB 1995, Jarvis 1992, Marsick 1987) (see website). This requires a cultural and psychological shift in ensuring that there are appropriate opportunities for utilizing the principles of experiential learning, and providing adequate opportunities for review and reflection.

APEL and APL present exciting possibilities for midwives, and are increasingly being used as a means to validate and add value to clinical practice. It is necessary to enrol in a university or further education college, and formally apply to have academic credit applied to clinical practice and learning in that practice. Time must be spent in preparing a professional portfolio documenting clinical activities, including evidence of critical reflection and a ‘claim’ for the academic credits appropriate to the clinical learning and development achieved.

Computers, e-learning and the Net

The development of computer-assisted learning and the growth of the Internet have revolutionized learning and information retrieval, and shortened the 5-year ‘sell-by date’ of knowledge. Midwives need to become comfortable using computers, and retrieving information through varied databases (see Ch. 5). Courses and programmes such as the European Computer Driving Licence (ECDL) can direct learning a variety of computer skills, including word processing and spreadsheet utilization (Jacob 1999).

Increasingly, modules and programmes of learning are available in electronic form (Jordan 1999, RCM 2010) (see website) and WebCT (web course tools) are being developed to support different facets of learning, offering notice boards, chat rooms and a range of guided learning facilities. Research suggests that students like the variety this offers, though the development of electronic packages is time hungry (Wilson & Mires 1998), and that students need different skills to work with e-learning (Valaitis et al 2005). The way in which learning takes place using e-learning and internet tools is different – even verging on the chaotic as the learner ‘surfs’ into different sites (Savin–Baden & Wilkie 2006) sometimes at considerable speed.

The Internet also offers other activities such as social networking possibilities, including ‘Facebook’ and ‘YouTube,’ which provide links with others, and access to PowerPoint presentations and video clips that can assist understanding of theory such as physiology (see website)

The NHS has provided information and resources to practitioners within the workplace. Initiatives include the National Knowledge Service (NKS) (NHS 2010), which covers clinical practice, healthcare, social care, and public health; providing a website of portals into databases and evidence-based resources, and can be utilized by patients and the public, clinicians, managers, and public health professionals. The aim of the NKS is to facilitate co-coordinating of a range of publicly funded activities that generate, procure, organize, mobilize, localize or promote the use of knowledge. NKS projects are currently being conducted for tuberculosis, oral health, diabetes, breast cancer and congestive heart failure. Other useful sources include the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Group (SIGN) (see website).

New approaches in education

Midwifery education links with other professions in interprofessional education, which can aid interprofessional working and understanding. Examples of this include the Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics (ALSO) and Neonatal Life Support (NLS) courses. Some pre-registration courses include interprofessional components in an effort to improve learning and working. Problem- and inquiry-based learning also provides an approach which is congruent with adult learning philosophy, enabling students to develop higher-level problem-solving and critical skills (McCourt & Thomas 2001, McNiven et al 2002, Savin–Baden & Wilkie 2006).

Learning and development

By the time students and qualified midwives have begun studying, they have gone through positive and negative experiences of educational activities. These include experiences of rote learning, tests and examinations, and inevitably some failures. Often, early negative experiences can colour people’s approach to learning and to their self-image.

There are many different models and theories around learning styles, and several questionnaires and quizzes which can be used to identify a person’s learning style. One is that proposed by Honey and Mumford (1992), based on work by Kolb, which suggested that people fit into one of four main groups:

One study identified that teaching reflection included a model incorporating surface, impersonal to deep personal, then surface personal and deep personal approaches (Miller et al 1994) (see website for more information).

Learning

The complex nature of learning has been explored extensively (Bloom 1956, Boud et al 1988, Bruner 1977, Freire 1972, Jarvis 1983, Mezirow 1981). The sheer breadth and depth of previous work within this area precludes more than an overview within this chapter.

There are many approaches: behaviourist, humanistic, the cultural environs, cognitive, through the spectrum to radical and emancipatory learning and education. Most of the earlier experiments and research into learning in humans were based on experiments with animals – even birds. Only during the development of ‘progressive’ education did research into human learning begin to be carried out. When looking at children’s and adult education broadly, there is evidence of a complex interplay of many of these different theories and approaches, and, indeed, in most situations, experience and how learning is approached are similarly complex.

Some learning theories, such as, conditioning, can be applied to simple learning, and applies in many situations – for example, in how individuals learn fear and develop phobias, as in Box 4.2, and how these might be diminished.

Box 4.2

Learning fear – applied to midwifery

Vaginal examination (VE) during labour – woman anxious, midwife perhaps does not realize the woman’s anxiety:

This example illustrates that it is possible to develop fear and anxiety from one or two negative experiences, leading to anxiety and panic at the thought of the examination, or even the sight of the midwife preparing the pack. This theory was reinforced by work by Dick-Read (1986), who advocated that those supporting women in childbirth needed to address the fear–tension–pain cycle, and this knowledge should inform the midwife’s support and education approach. This means providing a safe environment for the woman, sensitively identifying her previous experiences, fears and anxieties, and then planning how best to aid understanding and learning.

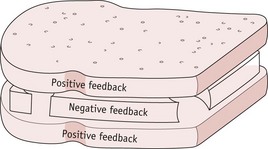

Behaviourist learning translates to providing feedback to the person learning – which might be yourself, the student you are working with, or the woman and family. Praise and criticism are substituted for food or electric shocks as used in behaviourist experiments, remembering that positive rewards are more effective than negative reactions (see Fig. 4.6).

Positive feedback is provided first: ‘You did x really well …’; followed by the negative criticism: ‘This needed to be done differently … because …’; and the feedback is completed with another positive comment: ‘This was really an excellent approach.’ The person is then left with a clear idea of what needs to be improved, but is not swamped by thinking that nothing that was done was right or good.

Trial and error learning can be understood by knowing that the theory suggests that the individual may try out different approaches to solve a problem, and then use that solution when faced with the same or a similar problem in the future (see website).

Cognitive Gestalt theory: Gestalt means pattern, shape or form, and describes the individual’s need to make sense of what is being seen and learned and put this into a ‘whole’. This problem-solving aptitude helps the individual gain insight into learning – the ‘Aha’ experience. Gestalt includes concepts such as insightful learning, the nature versus nurture debate, and field theory.

The individual’s natural tendency to seek understanding needs to be supported, though some gaps in knowledge may act as an impetus for learning. In teaching, this can be used to help make sense of what is being learned – perhaps planning a learning activity in which some information is provided and some not, so that the learner is encouraged to develop closure in composing the whole problem, and gets the experience of elements of discovery learning. Gestalt provided the tools for discovery learning and for the spiral curriculum which was taken forward by Gagne, in which new learning is linked with existing information.

This was developed in Bloom’s taxonomy of learning, which included three domains or categories of educational activities: cognitive (mental skill), affective (growth in feelings), and psychomotor (practical and physical skills). These domains are still used to set learning objectives, and in assessment (see Table 4.2). The taxonomy did not include the psychomotor domain; and therefore the experience of working with practical skills was limited (Bloom 1956), which echoes the difficulty experienced in healthcare settings of appropriately identifying and assessing practical skills and abilities.

Table 4.2 Taxonomy of educational objectives within the cognitive domain.

| Competence | Skills | Descriptive terms used |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge: |

List, define, tell, describe, identify, show, label, collect, examine, tabulate, quote, name, who, when, where, etc. Example: The student will list the major landmarks of the pelvis and fetal skull |

|

| Comprehension: |

Summarize, describe, interpret, contrast, predict, associate, distinguish, estimate, differentiate, discuss, extend Example: The student will describe the significance of the major landmarks of the pelvis and fetal skull |

|

| Application | Apply, demonstrate, calculate, complete, illustrate, show, solve, examine, modify, relate, change, classify, experiment, discover Example: The student will demonstrate the mechanism of labour describing the interaction of the fetal skull with the pelvis, and is able to teach students and women the basic principles |

|

| Analysis Of: |

Analyse, separate, order, explain, connect, classify, arrange, divide, compare, select, explain, infer Example: The student will be able to discuss the greater significance of different variations of shapes and sizes of pelves, and the effect on the mechanism of labour and outcomes. She may question the sources of this knowledge |

|

| Synthesis Production of a |

Combine, integrate, modify, rearrange, substitute, plan, create, design, invent, what if?, compose, formulate, prepare, generalize, rewrite Example: The student will be able to assess pelvic capacity and identify women who may have assisted labour difficulties. She may consider the effect of posture, mobilization and link research to this aspect of midwifery |

|

| Evaluation: |

Assess, decide, rank, grade, test, measure, recommend, convince, select, judge, explain, discriminate, support, conclude, compare, summarize Example: The student is able to merge her knowledge of the anatomy and physiology, with the research from major studies, and also the evidence of her own practice to provide the woman with unbiased choices, and aid her own process of problem solving and decision making |

Adapted from Bloom (1956) and Bloom et al (1964)

The spiral curriculum, used extensively in education, is a way of increasing depth of learning, built upon the importance of structure; readiness for learning; intuition as a productive but neglected area; and the importance of climate and teacher. The words: ‘teaching is a superb way of learning’ (Bruner 1977:88), and ‘[the] teacher is not only a communicator but a model’ (Eraut 1994:90), are useful things for midwives to think in their day-to-day life, in their own learning, and in teaching women and students.

The humanist theorists Carl Rogers and Malcolm Knowles are probably the most influential adult education theorists in relation to midwifery. Rogers proposed that students be given intellectual freedom, allowing them to direct their own studies (Rogers 1969, Rogers & Freiberg 1994). This manifested on midwifery education as the inclusion of self-directed sessions and negotiated programmes. The freedom concept cannot be wholly subscribed to, given the limited training time in which to learn and to be assessed as competent in certain skills in order to be deemed safe to practise (EC 1980, 2005, NMC 2008).

Knowles believed that the education of adults required a different approach to that of children, suggesting that pedagogy – the science of teaching – was no longer appropriate. He analysed this concept, which he initially viewed as appropriate only for children, and presented a new word – andragogy – the art and science of helping adults learn (Knowles 1973, 1980) (see Table 4.3).

Table 4.3 Comparisons of pedagogy and andragogy

| Pedagogy | Andragogy | |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Educating children in a didactic fashion – to lead | The art and science of helping adults learn |

| Learner | Dependent | Deep need to be self-directing Occasionally dependent |

| Learner’s previous experience | Limited Of little worth |

Rich reservoir of experience – resource for learning |

| Learner’s readiness to learn | When society says | When the individual feels ready – ‘need to know’ |

| Learner’s orientation to learning | Subject-orientated | Problem-solving Developing full potential |

| Teacher | Holds the knowledge In control of what and how learning takes place |

Is a co-learner Facilitator of learning experiences rather than teacher |

| Practical implications | Fixed set of knowledge to be learned, though with time and societal changes this alters | Need self-directed opportunities Problem-based enquiry Need to review previous experience (may prevent further learning) Need to explicitly value previous experience |

Andragogy was seen as a polar opposite to pedagogy, and it was presumed that it was inappropriate to use pedagogy for a group of adult learners (Knowles 1973). Later, he suggested that andragogy and pedagogy could be viewed as two ‘extremes on a spectrum’, used according to the needs of the student group of the time (Knowles 1980). This theory has been criticized for its assumption that adults are more self-directing than children (Tennant 1986), that adults differ from children in their ‘reservoir’ of experience (Jarvis 1983) and the different motivation and readiness to learn of the two groups (Tennant 1986).

Andragogy has been adopted almost completely by midwifery, as well as by nursing and other streams of education involving adults, though some aspects do conflict with the current directive to be cost-effective, reduce teacher–student contact time, and increase the student–teacher ratio. As well as philosophical differences, andragogical approaches require different classroom settings – desks and chairs arranged in semicircles or circles; more experiential learning; negotiated sessions where students set the agenda; and an increase in self-directed provision.

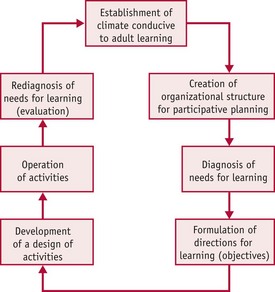

Teachers (or facilitators) used Knowles’ assumptions and processes in the delivery of sessions, and in designing programmes of learning which incorporated a process model (as in Fig. 4.7), in which the starting point is an environment which is conducive to learning, and the end point is an evaluation of the learning that has taken place, and identification of the next step required.

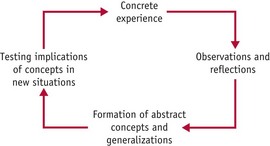

From andragogy to reflection

Another influential stream of theory emerged from Kolb (1984) developing experiential learning, which included reflection as the crucial link between experience and learning (Fig. 4.8). This was also incorporated into midwifery education – through increased use of experiential learning and reflection – and reflective practice has become an important component of the midwife’s daily work (Box 4.3).

Box 4.3

Practical illustration of reflective cycle

Normally, the cycle starts with the experience (at a concrete level) as something tangible to the senses of the individual. This might be the experience of a practical event such as witnessing a normal delivery. It might be that this delivery is a student’s first experience of witnessing a birth, and the woman in labour may react as some labouring women do, by being quite noisy, but as she enters transition becomes centred on herself. The baby is delivered, and it is a huge emotional experience. The student notes that the baby looks pink, but has blue extremities. She observes and reflects as she is part of this experience. The result is a sorting out in her own mind of the practical experience and her previous knowledge plus her ‘classroom knowledge’, and she begins to add to her personal knowledge bank. Each component of the experience may be processed separately according to her knowledge. If we look at one aspect, say the colour of the baby, she may make sense of it by thinking that this is the way babies are, and initially this simple acceptance might serve as a temporary working knowledge. Taking this to the next step of the cycle, she will then perhaps be expecting a pink baby with blue extremities at the next birth.

However, as she becomes more experienced and, hopefully, begins to learn more about neonatal physiology, she will appreciate that this is a visual illustration of the transitional effects of birth. She will also begin to understand the individuality of the experience, for the mother, midwife and indeed the baby.

Kolb’s work proposed that people fit into one of four main groups having a matching learning style, linked closely with the experiential learning cycle. The preference an individual has is congruent with their personalities, educational preparation, chosen career, or role function of the time (Kolb 1984) (see website).

Kolb viewed learning as a dynamic and fluid process, in which the experience and outcome are different for each person, and emphasized that, rather than being an empty vessel to be filled, the student enters learning with a range of learning and experience, and needs to ‘relearn’ rather than learn ‘from scratch’. The teacher therefore assists individuals to modify or dispose of old ideas and change their belief system (see website).

Experiential learning is an important tool in developing learning, in which more effective interaction with the concepts being taught is achieved, as the person is encouraged in a lesser or greater degree to actually sense what the concept would feel like. An example in midwifery would be students learning how to give ‘bad news’ to women and their families. This could be achieved by practising in a classroom setting what it feels like from the perspective of both the mother and midwife, and what words, body language or strategies are most caring and effective. A crucial part of this exercise is the debriefing and reflective phase that follows, during which all participants can present their perspective, and explore events and strategies together.

This type of learning is not always as easy as it might appear. To tell individuals just ‘to act it out’ does not provide enough guidance, and may result in limited learning or, in the worst case scenario, entering uncharted and unsupported territory.

If the midwife uses role play, either with student midwives or with women (such as during antenatal education), it is important to have a structure for the session (see website).

Reflection and reflective practice

The Reflective Practitioner (Schon 1983) described the crisis of the professions, popularizing reflection. Reflection was discussed by Aristotle, and later by Dewey (1933). Schon brought it to the attention of professions such as nursing, midwifery and social work. This book valued intuition and a more qualitative approach to problem-solving in practice, providing a means of understanding how practitioners make sense of and add to their repertoire of knowledge. Becoming a reflective practitioner has since become an ideal to which many practitioners aspire (Brockbank & McGill 1998, Driscoll 1994). Schon’s work describes a practitioner who chooses to utilize a technical rationality model and work logically to address the problems of the ‘high, hard ground where practitioners can make effective use of research-based theory and technique’, or alternatively take a more intuitive path through the ‘swampy lowland where situations are confused “messes” incapable of technical solutions’ (Schon 1983:42). Schon suggested that clients were more likely to have the sort of problems which required the more creative and holistic approach, and, in a period of time when nursing and midwifery in common with other emerging professions wished to develop their professional standing, this supported the more feminine, tacit nature of clinical practice.

Certainly, clients often present with a combination of risk factors, clinical and psychosocial problems, presenting a profile more akin to the swampy lowlands than those high hard grounds, and therefore this viewpoint is seductive. Though Schon described several ‘exemplars’ of teachers working with students to develop reflective practice, there was not really a clear tool available to assist a practitioner in developing the skills. Since that time, however, several other writers have published tools and frameworks to guide reflection.

It is often helpful to try out some of the many reflective tools to explore whether they can assist in making sense of experiences, and develop learning (see Box 4.4). This triggers questions to facilitate thinking about an experience or an area of practice, and develop it into learning (Atkins & Murphy 1993, Benner 1984, Driscoll 1994, Johns 1995). This includes critical incident analysis (see website), a term for an incident during which something went wrong, a crisis or a situation recorded for risk-management purposes, and also used in research and increasingly in the field of reflective practice to denote a variety of situations.

Box 4.4

A reflective model

The incident/experience

Plan of action

If truly subscribed to, reflective practice can be a potent model for the practitioner to audit day-to-day practice, and continue learning and development from the complex digestion and assimilation of theory and practice (James 2009). It is not without problems and requires significant time and energy investment, plus support (Macdonald 2002). It is seldom highlighted that reflection can be difficult, which means that many people will avoid thinking beyond the most obvious. It may also be uncomfortable as areas of practice are revisited – some long forgotten and some more enduring. Reflection needs therefore to carry something of a ‘health warning’, and an understanding that it is not always possible to reflect on all areas of practice all of the time (see website).

There is some evidence that just thinking about the individual’s philosophy generates some reflection (Kottkamp 1990) (see website for reflective activity). This is a useful means of articulating what is personally believed in as a midwife, and sharing this with colleagues. It is important to acknowledge at this point that reflection is an individual activity, and it is not possible to reflect for another person.

Reflective activity 4.2

Use the tool in Box 4.4 to reflect on an aspect of your practice – perhaps how you conduct a ‘booking interview’. You may wish to do this with a peer, or write it down as a reflective piece for your professional portfolio.

Reflection for you … and others

Others in the maternity service will be learners, who will need to be assisted through the reflective cycle, in order to make sense of their experiences. Student midwives usually have a clinical record and a clinical assessment tool in which they may be required to illustrate some critical reflection on their practice. They will, therefore, value working with midwives who are familiar with the terminology, and will also find it helpful to have a chance to reflect on different experiences and issues in practice. Sharing reflective incident analysis can be interesting and bring different perspectives, serving as an illustration to the student of how practitioners utilize reflection in day-to-day practice.

Perhaps most fundamentally, women themselves need to reflect. It is clearly not practical to ask women to complete pages of reflective accounts of their experiences, though some women may find this beneficial. It is good practice to review aspects of the woman’s experience with her, at a point where she has had time to consider events, and has begun to question what happened and why. The midwife can give the woman a unique opportunity for reflection on the whole continuum of pregnancy and childbirth. In reflecting with women, it is important to remember that, as in all reflections, she has to reflect on her own experience. Some trigger questions (Box 4.5) and a focus on her as the key player can be helpful, just providing information and clarification when asked to do so. Counselling skills (i.e. learning not to be quick to give a neatly packaged answer) are really helpful at this stage.

Box 4.5

Trigger questions for assisting the woman to reflect

Issues around debriefing may need more skilled support, and it is not unusual during the ‘routine’ reflections to identify a woman who may require additional counselling support.

Mentorship and the midwife as a role model

An important part of developing learning and practice is through interaction with others, and a powerful way in which humans learn physical, communication and caring skills is through the medium of role modelling. This allows absorption of the culture of the service (Hindley 1999), which may be negative as well as positive learning (Kirkham 1999), and even different parts of the service may have a different approach to mentoring (Kroll et al 2009). It may also lead to tensions for students when mentors are not practising in an evidence-based way, or contradicting what students are being taught in university (Armstrong 2010).

As a practitioner, it is important to be aware that actions, attitudes and demeanour may be perceived in different ways by students, other practitioners, women and their families and friends. Students, especially, are observant of their mentors, and may emulate their attitudes, though they tend to prefer the woman-centred and flexible rather than prescriptive approach (Bluff 2002). It is crucial to share the way decisions and judgements are made with junior colleagues – demonstrating how the very complex process that takes place during the woman’s care in the context of the service can be learned (see Box 4.6).

Box 4.6

The student learns …

Midwife X sees Mrs Brown, who is 32 weeks’ pregnant, with student midwife A. On examining Mrs Brown, the midwife feels that the fetus is not growing perhaps as fast as she would expect. She asks Mrs Brown about her nutrition patterns, and whether she smokes, drinks alcohol, etc. She provides the appropriate advice, but decides to ask Mrs Brown to attend antenatal clinic the following week. She therefore makes the appointment and records this in the notes.

Student A works in the clinic a couple of weeks later, and is encouraged by midwife Y to undertake the examination and the ‘talking’ under her supervision. Mrs Clarke is 32 weeks’ pregnant, and her observations are all within normal parameters – her fetus is growing well. Student midwife A makes an appointment for the following week.

Midwife Y is completely confused … surely this is not what they teach in the university these days! She challenges the student, and is actually a little sharp with her.

Not to share this process robs the student and practitioner of a valuable learning experience. This process of talking through what is being done and why – almost reflecting ‘on your feet’, which Loughran describes – can help students understand the thought processes an experienced practitioner has, and illustrates the complexities of those processes (Loughran 1996, 2000).

Students learn theory (and some practice) in the university setting, and the real world practice is learned from their mentors in practice (see website).

Conclusion

In considering aspects of learning and education, midwives must be aware of their own learning patterns, and be willing to review their own learning history. This will assist in planning education and development activities, and, more importantly, will assist them in analysing the learning and development needs of the women with whom they are working, and the students for whom they are responsible. The good teacher should be able to plan and assess learning, and this includes an analysis – even unlearning – of things that have been learned before; or unpicking and addressing assumptions that others may have about learning, or about the whole experience of pregnancy, childbirth and motherhood.

An important part of practice is to have a framework and tools which can assist in critically reflecting and assessing the effects of that practice. However, this requires the skills described many years ago of open-mindedness, wholeheartedness and responsibility (Dewey 1933). This does carry a health warning, in that truly reflecting on practice brings new challenges and perspectives which may not always be comfortable.

This chapter has reviewed the multifaceted nature of learning, education and development. As midwifery faces new challenges and different ways of working, it is paramount that midwives continue to learn and develop. To do so well will certainly benefit the profession and the individual midwife both professionally and personally. Most importantly of all it will benefit the care provided to women, their babies and families, and thus society as a whole.