Chapter 5 Evidence-based practice and research for practice

After reading this chapter and using the website, you will be:

Introduction

An essential skill for all professionals is using evidence in practice. Being able to determine the quality of research or information upon which evidence is based is a necessary skill for all midwives. Evidence-based healthcare should be the foundation for all policy decisions made within the health service and by midwives (DH 1997, 1999; 2008). Having the appropriate knowledge to evaluate research and evidence to assist in decision-making with women and families, appropriate to their individual needs, requires development of knowledge and skills with understanding of information, resources and women’s views.

Definition

At its most descriptive level, an evidence-based approach to healthcare involves basing decisions and actions on the best available evidence. Evidence-based healthcare (EBHC) can be viewed as a strategy, using a set of tools that enable practitioners to be aware of and locate the available evidence, judge its strength and soundness and be in a position to apply it in practice.

Central to the whole enterprise of EBHC is the concept of ‘evidence’; however, the term itself is confounded by complexity through different interpretations of its meaning.

What is evidence?

Evidence is a familiar concept within a legal context, where it has been defined as information which may be presented to a court of law, in order for a decision to be made about the probability that a claim is true. In other words, it is the information on the basis of which facts are proved or disproved (Keane 2008), where evidence is sought for the basis of clinical decision-making.

Judging what constitutes ‘sound evidence’ in healthcare can be problematic. Evidence can be drawn from a variety of sources:

While each of these may give rise to evidence which is adequate for making decisions in practice, they also have their limitations. Sources of evidence for practice are examined for their strengths and limitations.

Evidence used by a professional influences their decision-making in practice. The foundation for all decisions is the knowledge base of that professional. For forms of knowledge used in midwifery, see website. The knowledge base of a society is influenced by experts in the field (see website for expert opinions).

Research

All rigorous research is designed to produce evidence which gains strength because built into the research process are mechanisms that act as internal challenges to address some of the shortcomings identified above. This is true of both quantitative and qualitative research approaches, although they vary in the challenges they pose (Bryman 1992). The research process is systematic and logical with strategies to:

In designing and reporting research, it is essential to be clear in:

Quantitative studies will effectively:

Qualitative research must fulfil similar criteria, although the terminology used differs, arising from different assumptions about the nature of investigation that may arise from a problem or a research question (Denzin & Lincoln 2005). Researchers in this field will present support for:

Discussion of the above should be presented in the methodological descriptions in a research report that gives the research question, sampling strategy, data collection, tools, and analytical and ethical processes.

The research process is undertaken in a specific context and is shaped by the values and beliefs of those carrying out the study. Implicit judgements underpin all research activity. These include:

The decisions at each stage of the research process are generated within, and selected by, individuals whose worldview and values have been shaped within a particular social and professional context. Thus, knowledge is shaped by its social context (Davis-Floyd & Sargent 1997, Downe & McCourt 2008, Jordan 1993). In this sense, there can be no ‘absolute truth’. An awareness of this can be a fruitful basis for generating new questions which reflect and incorporate wider perspectives than just those of the medical or other professions.

However, even in its own terms, research cannot offer finality or certainty in its investigation of the world (Downe & McCourt 2008). Research studies can only present a partial perspective on the questions investigated:

All are subject to a variety of constraints, including the beliefs and values of the investigator. A study will be influenced by:

Even when these factors have been well considered and addressed within the research design and interpretation of findings, the applicability of results to wider spheres may be affected by small sample size, contextual factors or the acceptance of the study findings (see Downe & McCourt 2008) – for example, the series of studies carried out to investigate active management of the third stage of labour, in which selection of subjects, preparation of midwives and interpretation of data have all given rise to questions affecting the translation of research findings into practice.

Particular problems are encountered when a number of studies addressing the same issue present apparently conflicting results (see website for evidence dichotomies in interpretation of evidence in use for: steroids in preterm labour, the term breech trial and third stage management).

Limitations can be addressed in a number of ways. For a single research report, applying a strategy for rigorous critical appraisal (CASP 2010, Greenhalgh 2006) can enable the practitioner to distinguish between findings that are sound and those that are not.

Systematic review:

Techniques such as systematic review attempt to address the limitations of single studies and the ambiguity of study findings. This strategy involves systematically searching for a comprehensive sample of studies on a particular issue, including a wide range of publications and the so-called ‘grey literature’ of unpublished studies. It is an analytical tool to synthesize information (Brownson et al 2003).

Studies can then be selected for inclusion in the review, on the basis of explicit criteria applied to research method, and their evidence is evaluated.

A systematic review is a rigorous way of examining the methodology and findings of individual studies in order to overcome the limitations discussed above – for example, the problems of generalizing from small local samples or evaluating conflicting results. By validating study methodology and findings, the systematic review identifies those that can be confidently applied in guiding practice (Mulrow 1994).

Meta-analysis:

This further development of systematic review involves grouping similar studies and systematically applying particular research questions, as identified by a systematic review, and subjecting those data to further statistical analysis (see Enkin et al 2005, Olsen 1997, Olsen & Jewell 1998).

Whilst these strategies for comprehensive analysis can offer guidance for evidence, they are not without limitations (see Trinder & Reynolds 2000). It may be difficult to source the full range of information about a particular topic for study – for example, obtaining all sources, as a result of language differences, variations in the forms of study, or dissimilar inclusion and/or exclusion criteria. Furthermore, applying generalizable conclusions to a whole population may be neither individualized nor culturally or socially appropriate. However, the experience of dexamethasone demonstrates another obstacle to an evidence-based approach: ‘Despite repeated randomised trials in 1987 providing incontrovertible evidence in favour of antenatal corticosteroid therapy, obstetricians all over the world have been slow to adopt this treatment. The cause of this reluctance is unclear …’ (Crowley 2001) (see website for further debate).

Evidence derived from current literature, primary research studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses or in-depth literature reviews (Gray 2001, Hart 1998) are not the only form available to practitioners. Practice guidelines, issued by local NHS standard-setting committees, by the Royal Colleges with joint statements on best practice, government recommendations or WHO initiatives, when they are based on critically appraised evidence and referenced as such, present evidence in a form which is easily accessible and applicable to practitioners (see website for sources).

Hierarchy of evidence

The preceding section has considered the sources of evidence and knowledge forms (see website) used to inform clinical practice, indicating strengths and limitations of approaches.

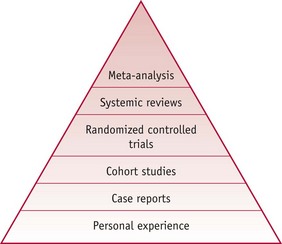

The literature promoting an evidence-based approach to healthcare (see Gray 2001, Greenhalgh 2006, Sackett et al 2000, amongst others) suggests a hierarchical order of value for different sources of evidence. This places a hierarchy in order of:

Methods at the ‘top end’ of the above hierarchy are valued more highly because they have mechanisms built into them which are intended to counter bias (Fig. 5.1).

However, it needs to be remembered that no one method is free from bias and therefore all evidence must be examined in a critical way before it can be used. Whilst personal experiences and knowledge are additional sources of evidence which should inform practice and research at every level, all evidence needs to be judicious in its use for each woman and baby and their individual context (Sackett et al 2000). Many issues requiring clinical decisions have not yet been studied in a systematic way and therefore personal experience and case reports remain important and essential in clinical decision-making (Walsh 2008).

What stimulates the search for evidence to use in practice?

The search for evidence may be generated when practitioners or service users try to challenge the perpetuation of traditional practices. Early research pioneers in midwifery used their findings to change practice and challenge traditions (Romney 1980, Romney & Gordon 1981, Sleep et al 1984). This may stem from the desire to confirm and disseminate personal approaches to clinical care (McCandlish et al 1998). Whilst it may arise from an interest in investigating the nature of midwifery practice, it may also be stimulated by the numerous debates that surround the provision of maternity care – such as antenatal care (Sikorski et al 1996), place of birth (Olsen 1997), nutrition in labour (Scrutton et al 1999), or midwifery-led care (Hatem et al 2008).

The two activities – conducting primary research to generate knowledge and critically appraising existing research findings – are closely linked. The further development of midwifery practice and care women receive depends on practitioners applying both of these activities in their professional lives with recurrent self-questioning of use of evidence to answer clinical questions.

Reflective activity 5.1

Reflect on your own experience and think of a question you may wish to ask yourself about current practice and whether this practice conflicts with evidence. Examples could be:

When you have decided your questions, use the guidelines below to find out the evidence.

Why search for evidence?

A midwife may begin a search for evidence to apply to practice for a number of reasons. The search may start with a question raised by:

It may be helpful to think about the process as consisting of a series of steps that can take the individual from a clinical question or problem, to finding, appraising and applying evidence that will help to answer it. The steps taken in developing the process of investigation for evidence are in Box 5.1 and will now be considered using a familiar clinical situation as a case study.

Resumé of case scenario

The case scenario concerns a midwife who is caring for a woman in normal labour in a hospital where there is a policy for limited eating and drinking in labour. (Full information may be found on the website.)

Framing an answerable question

The NHS Executive (1998,1999) commented that defining the question is the starting point of evidence-based practice, and that once healthcare practitioners are clear about the question, this will help in locating the evidence needed to discover answers to the problem. (For developing research questions, see website for Case scenario.) A guide for designing an evidence-based question is suggested by Sackett et al (2000) (Box 5.2).

Box 5.2

Elements in framing a question for a healthcare intervention

A question about a healthcare intervention contains four elements. These are:

This format would not be suitable for every question generated by clinical practice, and other formats should be considered when appropriate, such as where the questions relate to prognosis (Laupacis et al 1994), economic evaluation (Drummond et al 1997), and guideline evaluation (Oxman et al 2006).

Box 5.3 summarizes the elements recommended for constructing an answerable question and how they have been applied to the scenario.

Box 5.3

Elements recommended for constructing an answerable question (adapted from Sackett 2000) with examples relating to case scenario under discussion

Searching for the evidence

The process of tracking evidence in the databases is not as simple as it sounds on paper. It requires skills to navigate through the many different systems to find credible and trustworthy sources that have rigour. All healthcare professionals are now required to develop their Information Technology (IT) skills, to use the internal and external internet, databases and retrieve information. Computer literacy skills are necessary in all aspects of work (see website).

It is important to learn to navigate use of local guidelines and policies and ensure access to email so that you are kept up to date. Whilst there are a number of areas for which evidence exists to support sound decision-making, there are many clinical questions which still require evidence of good quality to be generated; this discovery in itself should be seen as a positive finding if it leads to further research. Clients, such as women and their families, may be more skilled at searching for information than are professionals but may not be able to discern the quality of research and evidence; therefore, sharing information with women is essential to assist them with participating in their care and decisions for their health and wellbeing. There is a case for involving women in developing the evidence and questions for practice (Soltani 2007).

The searching process

When undertaking a search, you will need to go through the steps in Box 5.4. (Refer to website for more detailed information and full explanations for Box 5.4.)

Some helpful hints in undertaking a search

If the search question relates to an intervention and its effects on outcomes, begin with a search of the Cochrane Database (see website). Cochrane will enable location of any relevant systematic reviews or references of trials relating to the question listed in the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register. It may be that the answer to the question is already available in the findings of a systematic review and further searching will not be necessary.

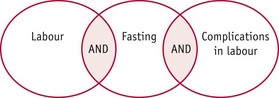

A search may work most efficiently if it is built up step by step, including new search terms one at a time (Fig. 5.2) (see website).

Judging the evidence

It may be tempting to look only at the findings of research studies or guideline recommendations relying on these to influence practice. However, it is necessary to exercise critical skills, even when the source of the evidence can be expected to have applied rigorous standards in its preparation.

Judgement can be exercised and developed by making use of the range of general and specific appraisal guides in order to validate the available research evidence, for example, Greenhalgh (2006) or Sackett et al (2000). A critical guide enables a systematic approach to appraisal, ensuring that attention is given to all elements of the research process, guarding against ‘snap’ decisions and ensuring that judgements are well grounded.

It is impossible to offer a comprehensive list of appraisal guides, as it is a rapidly developing area of literature (see website for references to guides). However, some resources that may be useful to develop a global way of appraising a research study include Rees (2003), Cluett and Bluff (2006), and Rudestam and Newton (2007), each of which provides a strategy for analysing and critiquing research reports. It is important, however, that you choose the appropriate guide for the question, topic and the form of report that you are appraising.

Some appraisal guides are developed specifically to examine clinical and related studies according to the specific research problem under investigation and/or the study design. Thus, there are guides specific to examining a clinical trial, a systematic review or a qualitative study of client experience. You will need a different set of criteria for qualitative and quantitative reports, as you will for appraising policy or other documents such as narrative enquiry.

Whatever the design of the study being appraised, it is helpful to use a tool specially designed for the purpose, which enables the important characteristics of the study to be examined.

Once the evidence is validated, the next issue to consider is how it is put into practice.

Contexts for implementing the evidence

The ‘practice’ of midwifery does not happen only when the midwife is ‘with woman’, and the application of evidence to midwifery can be regarded as happening at several levels of practice:

It is important for midwives to contribute to and engage in debates at all these levels in order to provide rational, justifiable, equitable and good-quality care for childbearing women.

Whilst at an individual level, it may seem relatively easy to implement change based on evidence – for example, individual midwives might examine and alter their usual practice – changing evidence-based practice is difficult when working in a context where practice is not consistently informed by good evidence. Thus, for example, many midwives face the difficulty of working in an environment where continuous electronic fetal monitoring is used in the care of most women, in spite of the absence of evidence to support this (Thacker et al 2001). This ‘evidence–practice gap’ is demonstrated in the case scenario about offering nutrition to women in normal labour (Scrutton et al 1999). So, consistent application of evidence to practice depends on more than the good intentions of individual practitioners.

Care for women and babies is delivered by many professional groups and individuals. In this respect, a ‘collective’ approach to evidence-based practice is essential. Implementation of evidence in practice is inextricably linked to the mechanisms for quality standards, risk management stategies and change within an organization. There are a variety of multidisciplinary activities, such as risk management groups, guideline and policy development initiatives, audit activities, and meetings looking at maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality, where midwives have to play a key role (see Ch. 7). Consultant midwives and practice development midwives make vital contributions in this sphere.

Midwives’ practice and use of evidence and research is shaped by influences beyond the local sphere and practice within a national professional framework (NMC 2004).

Supervision of midwives (NMC 2007) has a special and unique contribution to make in facilitating the development of an EBHC culture. An annual meeting with a supervisor (see Ch. 3) may assist in assessing the needs of a midwife’s development of knowledge and skills. Annual organizational audits for supervision of midwives may demonstrate practices that are poorly supported by evidence with action for change initiated.

A range of influences at the social level has relevance for creating a climate and context for evidence-based practice. In maternity care, multiprofessional critical appraisal of adverse events or client pressure, expressed through a range of user groups, has been pivotal in compelling professionals to re-examine the evidence base for practices. Such groups include the National Childbirth Trust (NCT), Association for Improvements in Maternity Services (AIMS), Active Birth Movement, Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Society (SANDS), and many others.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) was set up in April 1999 with the aim of providing ‘patients, health professionals and the public with authoritative, robust and reliable guidance on current “best practice”‘, underpinned by review of the available evidence. All midwives must be conversant with the publication of guidelines (see website). The NICE guidelines are based on a review panel of a multidisciplinary team, evidence-based and referenced with the aim to achieve consistency of practice nationally (NICE 2010). Midwives will also find helpful the RCOG Green-top guidelines that provide systematically developed practice recommendations (RCOG 2010).

Another initiative, which bridges the gap between service user and professional practice, is the DISCERN, a resource questionnaire that enables consumers to evaluate the quality of the information offered to them as part of their care (DISCERN 2010).

Evidence in practice for individual women

Publications by women’s organizations, such as the MIDIRS information leaflets (AIMS 2010, Birthchoice UK 2010, NCT 2010), all provide information for women. Furthermore, many women themselves have access to the internet and can manage to find their own information, though this may not always be based on evidence. Research reports are also published in the media and so keeping up to date with information in the public domain assists with discussing current anxieties that women may have. It is therefore essential that midwives fully discuss all evidence clearly so that women are fully informed to make choices and decisions with the midwife in their own best interest. The future will be to involve women in review of evidence for policy making (DH 2004).

Getting research into practice

The discussion of implementation of evidence-based practice can hardly be complete without considering the complexity of the process whereby evidence is translated into practice. Individual and organizational behaviours are important elements in the translation of research into practice. Two influences in a maternity setting are the commitment of all staff to policy and guidelines and the responses to the management of change (Bury & Mead 2000, Evans & Haines 2000, Haines & Donald 1998, Kanter et al 1992, NHS Scotland 2010, Sanders & Heller 2006). Without an active multiprofessional group to commit to revising guidelines and policies as new evidence becomes available, relevant to local needs and maternity philosophy, and reliable, there is little commitment to respond to change. It is suggested that it is essential to understand the characteristics of change and its impact on organizational activity, when embarking on implementation of evidence into practice (CASP 2010). Not to be forgotten is that evidence itself is subject to change. With further research and changing technology, the knowledge base for practice may alter very rapidly, so the search for evidence must be a continuing process.

A number of studies have examined the effectiveness of different strategies for disseminating and implementing research findings into practice. Bero et al (1998) conducted an overview of systematic reviews on interventions for the implementation of findings. Gawlinski and Rutledge (2008) suggest there is no one model for implementing research evidence in practice but offer a guide on a way to implement a change in practice. Kitson et al (1998) suggest the need to go beyond these linear representations of change, presenting a multidimensional model which takes into consideration three elements:

Each of these elements may be more or less favourable to the change process. Kitson et al (1998) propose that the model may be applied diagnostically to help in planning the implementation of change. The case studies they analyse suggest that facilitation of change is the key element to successful implementation. In the light of this suggestion, consultant or practice development midwives are strong candidates for initiating and sustaining research-based changes in practice.

Reflective activity 5.2

Rohini is 36 weeks’ pregnant. She has one son, Kishan. Kishan was born by emergency caesarean section for fetal distress at 38 weeks, 3 years ago. Rohini’s pregnancy has been uncomplicated. She is attending for her antenatal appointment today and asks you what her chances are of a vaginal birth this time around.

Consider what question you would ask prior to tracking the evidence for the above scenario.

Compare your question with our suggested one on the website.

Evaluating the implementation of evidence in practice

Like all change, the change process involved when evidence is translated into practice needs to be evaluated. A plan for evaluation may be part of the implementation process, or data may be collected through on-going audit activity (see Ch. 7), but there must be some thought given to measuring the impact of clinical change on client outcomes, organizational processes and staff activity.

Gray (2001) proposes an ‘evidence-driven audit cycle’. This is a useful model because of the way in which it integrates the search for evidence, translation of evidence into practice and measurement of its impact using audit tools. A question is generated within clinical practice, which stimulates the search for evidence. Changes in practice can be implemented on the basis of relevant evidence and the results of such changes monitored through audit activity. Evidence is made use of by being the basis for the audit standards against which practice is measured and a means by which further questions can be generated.

Conclusion

All midwives are required to use evidence-based practice (NMC 2008a and b). Whilst some midwives will apply bodies of evidence as interpreted in pre-appraised resources, such as The Cochrane Library and NICE, or in locally developed practice guidelines, others will take a more active part by contributing to the development of evidence-based guidelines. However, each professional is expected to use skills for searching and appraising current research evidence. Midwives may use research and appraisal strategies to challenge and change practice and some will engage directly in the research process: designing and conducting primary research, participating in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Whilst each of these activities requires different levels of expertise in the skills for EBHC, all of them require a basic knowledge of the research and appraisal process. The aim of using evidence-based practice in midwifery is to ensure women receive the care that offers the the best possible outcome for themselves and their babies.