Chapter 7 Governance in midwifery

Introduction

This chapter will initially focus on systems of governance within the NHS, primarily in England though the importance of governance in healthcare systems is highlighted in the World Health Organization (WHO) and European Health Observatory (for example, WHO 1997). This chapter intentionally provides a broad perspective on governance, because to improve midwifery care, midwives need to be politically astute and be aware of quality improvement practices both within and outside midwifery. For the purposes of this chapter, integrated governance, which encompasses both financial and clinical governance, is defined as:

’systems, processes and behaviours by which trusts lead, direct and control their functions in order to achieve organisational objectives, safety and quality of service and in which they relate to patients and carers, the wider community and partner organisations’

(DH 2006:11).

Good governance in healthcare is considered essential by the Council of Europe, which sets standards for health policy and considers the inclusion of ethics and human rights as essential within the framework of good governance (Council of Europe 2009).

NHS governance systems

The governance of maternity care is measured by outcomes for mothers and babies, particularly in relation to morbidity and mortality and, importantly, the satisfaction for women and their families with the service (see Ch. 16). Whilst governance encompasses quality, overall governance is reflected in the outcomes of providing a service that meets the needs of the population it serves and achieved within budgetary systems. Governance includes planning, strategic development, policy and guidance for practice with standards, audit and measurement linked to governmental strategic goals of the healthcare service and for maternity care, being mindful of the ethical nature of care. This includes clinical governance (see website).

The NHS

The NHS management and governance

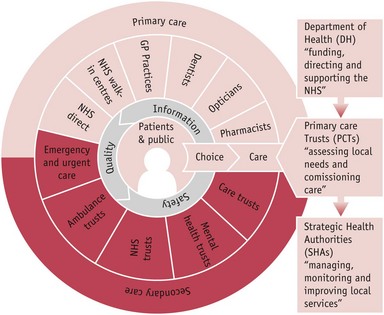

The UK Health Departments are accountable to Parliament for the management of the public money invested in health and social care (DH 2008a) (see website for further information) and the work includes setting national standards, shaping the direction of the NHS and social care services, and promoting healthier living. Figure 7.1 provides an outline of the different levels and networks of the NHS structure, some of which are referred to in this chapter and website.

Figure 7.1 NHS structure. (NHS structures are due to change in 2012/3.)

(Courtesy of NHS Choice website: www.nhs.uk/aboutnhs/howthenhsworks/pages/nhsstructure.aspx. Reproduced with permission.)

The Department of Health outlines the Government’s national priorities for the NHS and social care services through the annual publication of an ‘Operating framework’ (DH 2008b) (see Box 7.1). Each of these components of quality is expanded into activities, for example the NICE guidelines (NICE 2004, 2008), and includes the collaboration of other agencies in the quality of healthcare discussed later in this chapter.

Maternity care is one of the priority areas for the NHS, with an emphasis on normal birth (DH 2010a), particularly in relation to the reduction of health inequalities. Midwives need to be aware of the midwifery-related NHS priorities or Public Service Agreements (PSA), for example ‘reduce health inequalities by 10 per cent by 2010’, and their relevant measurements, such as ‘infant mortality and life expectancy at birth’ (DH 2008c:24) as money follows them. Funding and economic management are central to the governance of an institution (see website for Payment by results [PBr] and Ch. 14).

Strategic health authorities (see website)

The Government’s commitment to de-centralize its control of the NHS led to the establishment of the 28 strategic health authorities (SHAs) in 2002. SHAs have acted as the regional headquarters on behalf of the Secretary of State and their number was reduced to 10 in 2006 to deliver stronger commissioning functions. SHAs will be abolished in 2012/3 but in the meantime will lead and provide transition advice (DH 2010d). Key functions of the SHAs were strategic leadership, and organizational and workforce development, ensuring that local health and social care systems operate effectively and deliver improved performance.

Multi-agency bodies

Multi-agency bodies (MABs) are also termed ‘arms’ length bodies’ (ALBs). These regulate the health and social care system and establish national standards to protect patients and the public and provide central services to the NHS (see website). These are stand-alone bodies that support the Department of Health in its function. These may be classified into the following: Regulatory ALBs, Standard ALBs, Public Welfare ALBs, and Central services to the NHS. The bodies within these MABs/ALBs are given as examples (see website, also for other countries). MAB/ALB-style agencies are an important feature of other major health systems around the world, particularly in relation to regulation for health, such as hospitals and pharmacology. In the UK, MABs operate in three key areas:

They should also contribute and influence their work to enhance care and services for mothers and babies. Therefore, midwives should be aware of these bodies. By being aware of current evidence, research and women’s views, midwives can contribute towards policies that affect their practice.

NHS and quality

The Department of Health has set out its framework for quality in its ‘operating framework’ (DH 2010a) (see Box 7.2).

Box 7.2

Source: DH 2008b:16

A maternity-related priority within the NHS Operating Framework for 2007–08 (DH 2008b)

Primary Care Trusts do the preparatory work to support the achievement of the Government’s commitment that by the end of 2009 there will be a choice for:

The National Health Service is divided into different areas for care, with the woman and family being central to the services provided. Figure 7.1 reflects the range of services involved that need to work collaboratively with each other and with the woman and her family. Whilst services in midwifery are integrated between primary and secondary care, in other areas of the health service there are two different arrangements for governance of the primary and secondary healthcare services (see website).

Other types of NHS trusts are Acute trusts that may offer tertiary care, which manage hospitals, Ambulance trusts, Care trusts and Mental health trusts (see website). The majority of midwives are employed by either foundation or acute hospital trusts and are bound by their governance systems.

Additionally, the first-ever NHS Constitution has been published, with quality as a central tenet (Boxes 7.3 and 7.4) (DH 2009a, 2010c). The ethos of the NHS Constitution is respect, dignity and compassion, quality care, improving lives, with everyone being valued and working together for patients. The NHS Constitution makes national and local accountability clear by publishing what individuals can expect from the NHS, who is responsible for what, and how decisions about the NHS will be made. The Constitution applies to all those employed within the NHS, but regardless of employment within an organization or being self-employed, all midwives are governed by the rules, standards and codes of the UK regulatory body for nurses and midwives, the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC 2008).

Box 7.3

Source: DH 2010c:2,3

The National Health Service Constitution

seven key principles

Seven key principles guide the NHS in all it does:

Box 7.4

Source: DH 2009a

Rights and pledges for patients covering the seven key areas of the NHS Constitution

Reflective activity 7.1

How are respect, dignity and the compassion of care provided to women and their families in your maternity services measured, reported and acted upon?

Sixty years after the NHS was established, the full national Quality Framework will be in place (DH 2009a). The drive for quality healthcare was a founding principle of the NHS. Within the document High care quality for all, produced by the Department of Health (2008a), quality was defined as safety, effectiveness and patient experience. From April 2010, NHS care providers will produce annual ‘Quality accounts’ to provide the public with information on the quality of care they provide (DH 2008a). Along with a statement on the quality of care offered by the provider organization and a description of the priorities for quality improvement, Quality accounts report on locally selected indicators that will cover patient safety, clinical effectiveness and patient experience (DH 2009b). Some indicators for quality improvement (IQI) are published by the NHS Information Centre (2010) and others are being developed under the headings of effectiveness, patient experience and safety. Though there are limited maternity-related indicators to date, they will increase each year and currently include:

A limited range of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) have been introduced from April 2009 to measure outcomes as assessed by patients themselves (DH 2009c). Whilst not yet applying to midwifery care, PROMs are measures – typically short, self-completed questionnaires – which assess the patients’ health status or health-related quality of life at a single point in time, that is, effectiveness of care from the patient’s perspective (DH 2009c).

Now for the first time, a National Commissioning Board has been established to bring together all those with an interest in improving quality to align and agree what the quality goals of the NHS should be, whilst respecting the independent status of participating organizations. It will have responsibility for commissioning maternity services (DH 2010d).

Developing a vision and strategy

In 2008, the strategic health authorities published their 10-year ‘visions’ for the delivery of regional services within eight care pathways, one of which was for maternity and the newborn. Local NHS organizations are supported by SHAs to implement these ‘visions’ and midwives and supervisors of midwives will be instrumental in embedding the ‘visions’ in practice to ensure optimal midwifery care for mothers and babies. The final report of the Next Stage Review (DH 2008a) collated the visions of the 10 SHAs and provided the national picture of quality healthcare services fit for the future (DH 2008a).

The four themes underpinning the vision for the healthcare system are that it is:

Midwives need to influence the development of a vision for their own service and the measurement methods of the standards that will apply to midwifery care.

Quality in maternity care

Quality may be considered in terms of effectiveness, patient focus, timeliness, efficiency and equity. Poor quality, at times, may still be considered safe, but unsafe care can never be considered of good quality (Kings Fund 2008). High-quality care is delivered through clinical effectiveness, risk management, research, effective communication, lifelong learning, supervision and effective leadership, strategic planning and the efficient use of resources. Bevan (2008) supports this integrated approach and, additionally, purports that leadership and human dynamics are the key determinants to successful governance (see Chs 3 and 6). More national tools now focus on improving quality in maternity care. Some are included in Table 7.1 below.

Table 7.1 National tools to aid quality improvement in maternity services

| Focusing on normal birth and reducing LSCS rates tool (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement) http://www.institute.nhs.uk/quality_and_value/high_volume_care/focus_on:_caesarean_section.html |

| Implementation of the Productive Ward for maternity (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement) http://www.institute.nhs.uk/quality_and_value/productive_ward.html |

| UNICEF’s Baby Friendly Initiative (BFI) http://www.babyfriendly.org.uk/ |

| NPSA’s Intrapartum Scorecard http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/?EntryId45=66358 |

| RCOG’s Maternity Dashboard http://www.rcog.org.uk/womens-health/clinical-guidance/maternity-dashboard-clinical-performance-and-governance-score-card |

| Heath Innovation and Education Clusters (HIEC) High Impact Actions: Promoting normality (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement) http://www.institute.nhs.uk/building_capability/hia_supporting_info/promoting_normal_birth.html |

Clinical governance

Over the last decade, a raft of piecemeal complex governance systems, procedures, reporting frameworks, standards and inspection requirements have been implemented to provide reassurance on financial, safety and service quality (DH 2006). Since the 1999 Act (DH 2006) the corporate responsibility for quality and the first use of the term ‘clinical governance’, the aim of integrated governance has evolved to mainstream clinical governance as an internal planning, decision-making and monitoring activity for Health Boards on a par with money, probity and meeting national targets, with an increased priority on patient safety (DH 2006). Clinical governance is an umbrella under which come evidence-based practice, clinical audit, risk management, education, clinical or statutory supervision of midwives, research and partnership with users working together to continuously improve care. As part of implementing clinical governance, two government-appointed bodies were established to produce standards and guidelines to provide a national framework for standardizing and improving clinical practice – the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) and National Commissioning Board, a peer and lay body for assessing quality. At the local level, the essence of clinical governance is a partnership between women and professionals. Maternity networks provide an excellent forum for service users; that is, women and their partners to work with healthcare providers and commissioners to enhance multi-professional working, communication and collaboration for a united approach to clinical governance and practice, that are framed by the local guidelines, policies and standards. Although providing guidance, their importance is at the interface of the service between professional groups and women and their families. The responsibility is for midwives, medical staff and other professionals to collaborate to provide a service in which the same standard is met by all professionals caring for women.

Joint statements by professional bodies are aimed to assist professionals to work and collaborate in providing safe and effective care (RCOG RCM 2006, RCM RCOG RCP 2006, RCM RCOG NCT 2007) (see website for examples). Good practice requires that these statements are used by groups of professionals in maternity units to discuss and see where local developments and changes need to be made when determining local policy (see RCM RCOG 2007).

Policies, guidelines and standards

Each healthcare provider, and therefore every maternity unit, is required to have guidelines, policies and standards for the safe, effective delivery of care (see website). While National Service Frameworks (NSF) (DH 2004) are being implemented to introduce national standards for specific services or care groups, such as women, their partners and babies, clinical practice guidelines underpin the national standards. Both must be interpreted locally to provide quality to meet the needs of the geographic and demographic populations: an ideal forum being the maternity networks.

NICE provides patients, health professionals and the public with authoritative, robust and reliable guidance on current best practice. For example, it has produced guidelines such as NICE 2004, 2006a&b, 2007a&b, 2008. The Royal College of Obstetricians’ evidence-based guidelines, for example RCOG 2008, are also useful. All guidelines and associated standards of practice are required to be based on best evidence. An example of use of evidence and research is given on the website (and see Ch. 5).

Midwives must ensure that they articulate the benefits of the current research and evidence when discussing midwifery care and when services are commissioned; for example, a recently published Cochrane review concluding that evidence of improved outcomes, with no adverse outcomes, indicates that all women should be offered midwife-led models of care, as opposed to medical or shared-care models of care (Hatem et al 2008) (see website).

Guidelines and standards act as performance indicators against which progress is measured within an agreed timescale. Standards are objective assessments against which measurements of effectiveness may be made through the processes of audit.

Audit

Audit in maternity care has many forms (see website). Audits are undertaken clinically to measure standards of practice against national benchmarks, for example in perinatal and maternal morbidity and mortality statistics (see Ch. 16). Surveys take place to audit patient satisfaction (see website for the national study by Green et al 2003). Each maternity unit should undertake regular satisfaction surveys of all areas of midwifery care to assess women’s view of the care they receive and if these achieve the expected standards. These audits will also demonstrate areas for improvement.

Each maternity unit will publish its local statistics and monitor, through the local NHS trust, generic indicators of effectiveness and efficiency of the health service, such as measurements of infection rates, health and safety issues, sickness and absence rates. Maternity indicators of health, such as rates of breastfeeding, midwife-led care, normal births, one-to-one care in labour, reducing anaemia and smoking in pregnancy, provide an indication of the quality of care in a maternity unit. Audit extends to reviews of both qualitative and quantitative measurements. Both measurements can be advised to demonstrate quality of care. Audit of risk factors over a shift and over monthly time-spans are utilised in the NPSA Intrapartum Scorecard and the RCOG Maternity Dashboard. These nationally recommended tools benchmark the acuity and outcomes of maternity units to present contemporary data to act as ‘flags’ to Trust Boards to ensure that resources provided to maternity units are sufficient to enhance good outcomes.

Management of risk

Managing risk is a fundamental element of clinical governance. Risk is where there is perceived harm or injury that may occur as a result of care. Managing risk is aimed at preventing and reducing risk that may occur as a result of care which is below an acceptable standard.

Risk management aims to improve the quality of care, prevent occurrences which may harm clients or staff, reduce the risks of adverse events and reduce costs to healthcare providers. The aim of managing risk is to minimize adverse outcomes. This process begins by identifying and assessing risks, such as poor outcomes and ‘near-misses’, through critical incident reporting which is followed by prompt, open investigation. Why something went (or nearly went) wrong is established, not to apportion blame, but so that processes can be put into place to prevent recurrence. Poor performance is addressed and other lessons learned, with the overall aim of improving care and reducing complaints and litigation.

Whilst the aim is to improve maternal and perinatal outcomes, it is important that the processes do not ignore the individual choices and preferences for care that women may make. The midwife must be clear of her role and accountability in supporting women. In this a midwife needs to keep herself infomed of current developments and evidence and ensure her own education (see Ch. 4).

When standards are not met – learning from failures …

In recent years, concerns have been expressed about the quality and safety of some services, including maternity (Healthcare Commission 2008a, Kings Fund 2008). Also, concerns about individual practitioners and institutional management (see website) have led to a review of medicines laws, the White Paper on the self-regulation of healthcare professionals (DH 2007, 2008d), and organizations such as the National Patient Safety Agency, a body with a remit focused primarily on safety.

Poor leadership has been implicated in a number of Healthcare Commission investigations into poor-quality services, including maternity services. The Care Quality Commission is the independent single regulator for health and social care (CQC 2010). It provides validation of provider and commissioner performance, using indicators of quality agreed nationally with the Department of Health. It publishes an assessment of their comparative performance in the annual healthcheck and has made commitments in a 5-year plan to focus more improvement and monitoring work on maternity services (CQC 2010) (see website).

Box 7.5 indicates common themes that occur within the investigatory work of the Healthcare Commission (Healthcare Commission 2008b). The failings reiterate everyone’s roles and responsibilities in relation to integrated governance, from individual clinicians, to managers, Trust Boards, commissioners, regulators, and strategic health authorities (DH 2009a).

Box 7.5

Source: Healthcare Commission 2008b

Common themes within the investigatory work of the Healthcare Commission

Additionally, it is important to recognize that NHS staff who ‘whistle-blow’ on aspects of safety, have full protection under the Public Interest Disclosure Act. Employers have a duty to support staff in doing so and midwives have the accountability to do so within their Code (NMC 2010a&b).

Within a maternity unit, failures are identified through the incident review and management procedures, with regular reports and analysis of incidents and near-misses. It is good practice to review regularly good and problem case scenarios in an environment that is without blame, bringing together all multi-professional groups. This should be an educative process, sensitively managed by each profession involved, to ensure that no individual is targeted for fault but rather the systems, and areas for improvement and lessons to be learned to improve collaborative practice are identified.

Defective practice, lack of knowledge and poor communication are commonly found to be causes of avoidable maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity. Whilst these problems may never be completely eliminated, much can be done to improve care by evidence-based practice which is regularly and rigorously audited and acted upon by addressing deficiencies and ‘near-misses’ through management or statutory supervision of midwives.

The role of supervision of midwives

The Kings Fund acknowledge that maternity services have:

‘a strong tradition of championing safety, of pioneering quality initiatives (such as the drives for woman- or family-centred and evidence-based care) and of using women’s views to inform service planning’

(Kings Fund 2008:14)

The Kings Fund also recognize that supervisors of midwives have a key leadership role in the safety of maternity services and that whilst safe healthcare is often linked with quality, the relationship between safety and quality do get confused. They outline that quality of care critically encompasses safety.

All practising midwives have a named supervisor of midwives to support them in their practice. Midwives would risk breaching their accountability by not upholding their Code if they were complacent within an organization whose governance was not optimal, or if their own practice was not of a high standard (Box 7.6). Statutory supervision of midwives supports midwives in practice to protect mothers and babies. Established as an inspectorial function to lower maternal mortality rates, it has evolved to:

Box 7.6

Source: NMC 2008

Principles of the Nursing and Midwifery Council Code (2008)

The people in your care must be able to trust you with their health and wellbeing. To justify that trust, you must:

’support protection of the public by promoting best practice, preventing poor practice and intervening in unacceptable practice’

(NMC 2007)

The roles and responsibilities of supervisors are, amongst others, to monitor standards of midwifery practice, contribute towards risk management and clinical audit, investigate critical incidents, and provide leadership which supports and empowers good practice through women-centred evidence-based decision-making (NMC 2007). Working effectively, statutory supervision of midwives contributes significantly towards clinical governance in producing first-class maternity services.

Future quality issues

Two reports commissioned by the Department of Health explored the future funding issues faced by the NHS (Wanless 2002, 2004). The reports articulate resources required for the NHS to cope with increasing expectations, an ageing population, a rise in lifestyle disease, and the cost of new treatments and technologies (DH 2008a). The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), an independent non-profit organization working to improve healthcare throughout the world, argues that 21st century healthcare should adopt new ‘rules’ (Table 7.2). Its ethos of ‘all teach, all learn’ brings together committed individuals and organizations, recognizing that more healthcare improvements can be achieved collectively than individually (IHI 2008).

Table 7.2 The Institute for Health Care Improvement (IHI ) ten rules

| The old rules | The new rules |

|---|---|

| Care is based on visits | Care is based on continuous healing relationships |

| Professional autonomy drives variability | Care is customized according to patient needs and values |

| Professionals control care | The patient is the source of control |

| Information is a record | Knowledge is shared and information flows freely |

| Decision-making is based on training and experience | Decision-making is evidence-based |

| Do no harm is an individual responsibility | Safety is a system property |

| Secrecy is necessary | Transparency is necessary |

| The system reacts to needs | Needs are anticipated |

| Cost reduction is sought | Waste is continuously decreased |

| Preference is given to professional roles over the system | Cooperation among clinicians is a priority |

Source: IHI 2008

The latest Operating Framework (DH 2010a) makes moral and financial arguments for optimizing the health of newborn babies to reduce the demand for neonatal care, thereby realizing health, wellbeing and cost benefits in the future. It recommends tools now available to support the NHS in improving maternity and neonatal services (see website). This will be even more challenging as the transition towards structural reforms occurs which highlights the important roles of midwives in driving the quality within maternity services (DH 2010e, DH 2010f).

What governance means for midwives

Midwives need to be innovative, to build on existing structures and processes and develop new ones in order to embed excellent practice. It is vital to have midwifery representation in the decision-making processes involving procurement of systems and to ensure that systems are flexible enough to introduce developments which can improve care and be audited easily (preferably by a clinician) to monitor standards of care. Midwives also need to be aware of and act upon the views of women and families regarding the maternity services. Midwives need to be knowledgeable and adapt their care for and argue on behalf of women for the care required within the local community.

Computers are increasingly being used to store clinical data, replacing paper-based records and documentation. Electronic materials such as antenatal bookings can be utlized for clinical audit and financial purposes – for example, data for Payment by Results processes. Midwives need to seize opportunities to use these systems to improve care. Flexible clinical computer systems lend themselves extremely well to incorporating prompts and audit tools which appear on screen under specific conditions, taking little time to complete and, with appropriate software, being easy to audit. Successful innovations in this and other areas should be shared through publication, conferences, and other local and national forums.

In all areas of governance, ethical considerations are paramount, as maternity care involves people (women, babies and families) and harm may arise when any system of governance changes unless consideration is given to the outcomes of this change (Walsh 2003). Ethical issues will continue to challenge midwives as economic constraints change the way we practise and new developments, such as advanced and comprehensive screening tests, become ever-more sophisticated.

Whilst midwives will focus on the care of women, this should not be only on the narrow issues of providing individualized, quality care to women, babies and their families. Midwives do not practise in a vacuum but in a local context, with their peers, obstetricians, paediatricians, anaesthetists, GPs and paramedical staff. They need to be aware of their contribution to wider public health issues that impinge upon maternity care, such as mental health, social inequality, or disability care. Over the last few years, midwives have at times retreated into their world of midwifery and have sometimes minimized or even dismissed the contribution of their professional colleagues. Midwives need to contribute meaningfully to multidisciplinary policies, protocols and guidelines in order to improve standards of care and universalize good practice, whilst retaining their unique and distinctive role.

Midwives have an important part to play and their impact should not be underestimated. Reducing smoking in pregnancy, cot death, teenage conceptions; promoting breastfeeding, healthy diet, parentcraft education; and meeting the needs of socially deprived women are just some of the issues on which midwives can and do have enormous influence, not only on women, but also on their partners, families and beyond. Auditing and monitoring these areas may contribute to wider public health knowledge. Nationally, midwives need to be at the forefront of policy-making processes around maternity care, such as contributing to Midwifery 2020 (NHS et al 2009). At a national level, midwives should grasp opportunities to work more closely on policy.

Conclusion

Quality of care in midwifery is that which demonstrates competent caring, tailored to individual women. It aims to involve the woman and her family so that she experiences as positive and safe and normal a pregnancy, delivery and puerperium as possible. The midwife whose practice is woman centred and evidence based, working cooperatively with her peers in her local situation and being aware of her unique role and contribution in the wider context of society, is ideally placed to have an impact on both the short-term and long-term health and wellbeing of mothers, babies and their families.