Chapter 12 Psychological context

Introduction

Each woman reaches pregnancy by a different road. Some women will have chosen very carefully to have become a mother and be excited by the prospect. Others will have become pregnant earlier than they had wished, whilst some will be unhappy to be pregnant. This last-mentioned group may include those women who have become pregnant by violence or force. It is important therefore that midwives remember that each woman and her family will need care which is planned and organized to support in their individual journey to becoming a family. Midwives need to have great sensitivity and awareness of the processes and dynamics of communication. They may then address the anxieties, fears and worries, often not spoken about by women, but which still need to be made explicit so that appropriate care is offered to women in their individual family units.

In any work on psychological processes or communication, it is important to remember that before we begin to work with others we should examine ourselves, because how we behave and how and when we speak will impact on women, students and other healthcare practitioners with whom we work. In addition, the relationships we develop with a woman and her partner will influence the way a woman experiences her journey to motherhood, and the psychological aspects of her care.

Relationship

It has been recognized for many years that it is the depth and strength of the relationship between client and therapist that makes the difference (P Clarkson, personal communication, 2000) (see website for Case scenario 12.1). This bond or working alliance enables the client to explore their situation and change or remain the same, depending upon their decisions following explorations of their circumstances.

The concept of relationship is so obvious that it is often taken for granted; however, anecdotal evidence and research (Griffith 1990) suggests that it is frequently missing in general practice. Yet, this is an area where clients may have a lifelong provider of care. If this is true in general practice, it could be similar in midwifery.

Women are having fewer babies than formerly. Pregnancy is a time when women may feel vulnerable because so many changes are occurring at such a rapid pace. The meeting with the person who will provide care at this time is important. Some people really enjoy change, it is exciting; others dislike change, as it provokes anxiety, which they try to avoid because they wish for stability or for their life to remain the same.

For some women, the relationship between themselves and the midwives whom they meet may become very important. Women who are without an extended family network or friends are often socially isolated. It is common knowledge that such ordinary human relationships can have a psychotherapeutic value (Clarkson 1996). Women who have a poor relationship with their own mothers and few friends may experience difficulties in pregnancy, childbirth and the first year following the birth of their baby, if they do not receive adequate support from the midwife or a therapist (J Harman, unpublished PhD thesis, 2008). A sound relationship with the midwife will provide stability for the woman and reduce her experiences of anxiety or fear, enabling her to develop confidence in herself.

For a relationship to develop or establish, three components are required:

Trust

All adults realize that an individual can betray them; therefore, trust does not exist overnight in any relationship and has to be earned. It has long been recognized that if we have similar traits to another person then we are more likely to like that person, relax in their company and be influenced by them (Cialdini 2001). Women also expect a midwife to ‘look after them’ or act in their best interest, thus to advocate for them (Fraser 1999). Advocacy goes hand in hand with trust, and this means that midwives need to trust and believe in a woman’s ability to be pregnant and give birth so that the woman will believe in her own ability to be pregnant and give birth.

However, in today’s maternity services, risk management is an important aspect that influences the ways in which midwives practice. In a hospital setting, midwives respond to the influences of senior practitioners and will change their behaviour to obey or conform to their senior’s wishes (Hollins Martin & Bull 2008). If a woman sees this, she may feel differently about her midwife, perceiving that if the midwife conforms, the woman herself may consider the need to conform. If she conforms, she is seen as a ‘good’ patient. If she does not conform, she may be considered to be a ‘problem’ patient.

Women may prefer to be seen as the good patient, because the fantasy is that care will be kinder or better. However, the decision to change her behaviour and accept the care offered by a senior practitioner may result in the woman no longer feeling that she has choice, control or a voice to influence what happens to her during her pregnancy or labour. The trust she has in the midwife may be breached and may be irreparable. The woman may also feel angry with herself for not being stronger. She may consider herself weak and if she thinks this about herself, she may also think the same about the midwife.

A second aspect of trust is that if the midwife or student midwife is confident in her own ability to provide care to women and their partners, they, in turn, will have confidence in the midwife. The woman will feel safe. Often women are happy to be cared for by ‘brusque’ midwives because their behaviour displays confidence, whereas sometimes a very kind midwife can display behaviour which shows a lack of confidence, consequently the woman feels unsafe.

It is important for midwives to develop confidence and competence so that the care they offer to women provides feelings of safety to build trust. However, many students and midwives do not feel confident or competent at the point of registration (Donovan 2008). This perceived lack of confidence and competence will affect the woman/midwife relationship. During her student training, each midwife needs to be nurtured by a mentor who facilitates her practice, providing praise when it is due, encouraging the making of decisions when appropriate and discussing the decisions made (Currie 1999). Consequently, when students qualify and begin to work independently, they do not display or experience anxiety, thus women will feel safe in their care. As a result, an individual woman will be willing to tell the midwife her personal story, which will facilitate accurate history-taking and lead to the appropriate provision of care for the woman and her partner.

A third aspect of trust is compassion, which can also equate to un-possessive love. It is a challenge for midwives to remain compassionate when they are working under pressure. Midwives may work in a delivery ward where there are too few midwives to offer continuous support for women in labour. The pressures may lead to little or no time to comfort a midwife who has attended and been affected by a difficult birth. What happens is that the midwife becomes psychically numb. She switches off her empathy and compassion to protect herself and as a consequence she can be perceived and experienced by women as uncaring and unkind (Kings Fund 2008). The midwife no longer conveys the sense that she understands the experiences of the woman and wants to do something about it (Youngson 2008).

Respect

Respect for women is the foundation on which all meetings or interventions are built (Egan 2007). It is a way of seeing the woman as a unique individual and is based on maintaining a woman’s dignity. The midwife needs to convey in her way of being that she will not cause any harm and that she is skilled, competent and confident in her practice of midwifery. The midwife needs to convey to the woman that she is her advocate and will be with the woman on her journey. This does not mean though that the midwife would collude with the woman. If the woman is drinking more than the recommended amount of alcohol units per week, the midwife will point this out, because this behaviour needs to be challenged. The midwife works on an assumption that women wish to live healthily, so if the woman resists, she will also recognize and respect that it is her right so to do. It is important that midwives are able to suspend judgements; most people are their own worst critics, so women do not need other people to judge them as harshly as they may judge themselves. Respecting women is to keep them as the focus in order to provide woman-centred care.

Communication

This refers to proficient and appropriate use of specific skills. Many people believe that they are good communicators, yet when asked to identify which communication skills they are using, they are unable to do so. If an individual is unable to identify which skill they are using, they are often not using the skill most appropriate for the situation. Communication skills need to be practised and fine-tuned so that they are used every day. As midwives interact with women each one may require different skills in order for her to feel valued, listened to and understood.

When all three of the above aspects are present, a woman will experience a satisfying relationship that will enable her to cope with the changes which occur during pregnancy, labour and early motherhood.

The dynamics of communication processes

A simple explanation of communication is that one person speaks to another, who hears and understands what is said and responds to the speaker, as in Figure 12.1.

The diagram shown in Figure 12.1 is very simplistic and does not allow for the complexities surrounding human interaction. What are important to take into consideration are the factors that impede our ability to listen to ourself and others.

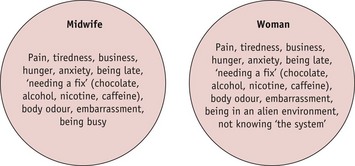

Figure 12.2 illustrates some of the factors that midwives, students and women may experience every day which will impede their ability to listen. The factors may be present in one or other or both parties.

Bearing this simple diagram in mind, it is important that each practitioner takes responsibility for themselves to minimize as much as possible the avoidable/preventable factors for both herself and the woman, so that when meeting a woman she can interact with confidence. All of the factors in Figure 12.2 will act as barriers to a relationship developing.

Specific communication skills

Communication via body movements and facial expressions take place rapidly and what a person sees may inform a decision-making process more than what is being said or heard. How much we communicate non-verbally continues to be debated. Hargie & Davidson (2004) suggest that what is said contributes a mere 7% of the overall message conveyed. If this is so, then it is important for midwives to become skilled in observing individual women. For example:

n.b. It is also crucial that the midwife is aware of her own body language, and verbal and non-verbal cues that she might emit, and how these might be translated and understood by the woman and her family.

Reflective activity 12.1

It is also useful for midwives to look at themselves in a long mirror and see what the women would see. Not, maybe, a 360-degree mirror, but one in which you see yourself as others might see you. Then ask yourself, do you like what you see? If you do not like what you see, what can you do so that you will like what you see?

This activity may be quite simple: smile so that the smile reaches your eyes; change your hairstyle/colour of your hair; or stand with your head up and your shoulders back, which will immediately make you look 10 lb lighter, and reduce back pain and headaches.

Non-verbal communication such as smiling, nodding your head and beckoning in a welcome expresses warmth and friendliness to the woman. When speaking to a woman it is important to use words that, to her, have a meaning to them and include, with explanation if necessary, professional midwifery terminology so that the midwife does not appear to be condescending. Should the woman see another healthcare practitioner who uses professional terminology, the woman will not feel confused or overwhelmed because she has heard the words previously.

It is important to demonstrate your attention. This is mainly conveyed through body language. Egan (2007) developed the acronym SOLER. Prior to meeting a woman for her appointment, it may be useful to repeat the acronym to prime yourself. It is a way of letting go of the previous interaction to focus on the next.

Once the woman is sure that she has your attention, it is then important to demonstrate that you are listening to her. At first, passive listening whereby you indicate by para-linguistics, the ‘Mm …’, ‘yes …’, ‘ok …’, ‘ahum …’, ‘right …’, using head nodding and eye contact indicates that you are listening. The same technique can be used whilst speaking to the woman on the telephone to indicate that you are listening and attentive. Be aware that if you are smiling as you talk, this may be transmitted.

What becomes more important is to actively listen, because this will demonstrate not only that you have been listening but also that you have understood. It is this which informs the woman that you do care and that she is an individual.

Active listening

This involves the use of reflection, paraphrasing, questions and demonstrating the traits of empathy, unconditional positive regard (warmth) and genuineness (see website for Case scenario 12.2).

Reflection is the skill whereby the midwife, having listened to the woman, will repeat one or two words back to her to encourage her to continue with what she is saying. If the midwife is not skilled in this, it can sound as if you are mimicking the woman, or just repeating what she has said (Egan 2007). The words are said in the same tone that the woman says them, rather like an echo, so that they resonate in her mind and act as a prompt to go on with what she has been saying.

Paraphrasing is the skill whereby the midwife has listened to the woman and then restates in the midwife’s own words what the woman has said, the core of the statement (Adler & Rodman 2000). The use of her own words demonstrates that she has absorbed the information, that she understands. Thus, the woman feels understood and supported. If the midwife has incorrectly understood, it gives the woman the opportunity to correct the misunderstanding.

Questions can be open, closed, directive and multiple. Many practitioners will ask closed questions, mistakenly thinking that they are open. Too many closed questions can cause women to feel that they have just been interrogated and leave them feeling exposed and vulnerable with, for some, a sense that, ‘I don’t want to go through that again’.

It is useful for students to practise with each other, taking full records at an initial visit. This can be followed by giving and receiving honest balanced feedback, remembering to give praise so that lessons are learnt. Audio taping or videoing such a session is even more useful because it is then possible to hear and/or see oneself. Many people do not like undertaking such exercises, because they are false; however, if the student performs well in the exercise, then it is likely that the real situation will be even better.

Empathy is the ability of the midwife to sense the woman’s inner world and communicate that back to the woman. This can be really important when the woman is from a different culture, because she will feel accepted by the midwife.

Genuineness is the ability of the midwife to be her real self when working with women and not hide behind a professional façade. Communication from the midwife to the woman should be clear and the midwife clearly hears what the woman has spoken (Egan 2007).

Unconditional positive regard is the ability of the midwife to see a woman as a unique person, who is important and whose contribution is valued. If the woman is a drug user, even though the midwife will challenge her in her use of drugs, the midwife still makes clear that she is valued and accepted as a person.

The above skills and traits, used well, will enhance the midwife/woman relationship and enable midwives to perform their functional role, that of midwife; and will assist in identifying whether the woman needs to be referred to a counsellor for ongoing support.

Therapeutic counselling

The midwife is not a therapeutic counsellor; she is a midwife and, as such, needs to learn when to refer women to therapists. Some NHS trusts have specially qualified midwives who can offer ongoing support for women and their partners. Sometimes a midwife may not be able to maintain an emotional distance from a woman and this means the midwife may over-identify with the woman. If this occurs and the NHS trust employs a midwife counsellor who works with women and their families, it would be useful for the midwife to speak to the counsellor to assist the midwife to regain her equilibrium.

Improving midwifery care

Substandard care caused by poor communication has resulted in the deaths of women (Lewis 2004). This means that every student and midwife must examine communication skills to identify where improvement is necessary. A skills audit and checklist (see website for Tables 12.1a and 12.1b) will assist midwives to identify their own communication skills.

Interpreters

When a woman is unable to speak English, it is important to offer her the use of an interpreter when she attends for care. However, it is important that interpreters have adequate training so that they ask the questions the healthcare professionals have asked. They need to report back to the midwife exactly what the woman or her partner has said.

It is important that trained or professional interpreters are used so that they do not make assumptions about the woman’s answer as this may affect the woman’s care adversely. The use of children and family members must be avoided because there may be a lack of understanding of the importance of the questions being asked, or the family member may be reticent to ask the questions owing to feelings of modesty or embarrassment (Bramwell et al 2000) (see Chapter 23). It is important to remember that it takes time to arrange a professional interpreter, which may be impossible during an emergency or during labour (Iqbal 2004). If at all possible, it is important to use the same interpreter at each visit. This will enable the midwife, interpreter and woman to build a trusting respectful tripartite relationship.

Psychological aspects of pregnancy

Each woman will react to the news of being pregnant in a manner relevant to her individual situation. Many changes take place in the childbearing year, physically, emotionally and socially. Physical changes occur whether the woman wants them to or not, although some women will fast to minimize the amount of weight they gain in pregnancy. Some women relish the new identity of mother and adapt without any difficulties; other women do not and find the change of identity difficult, particularly if there has been a difficult relationship with their own mothers, for example, over-controlling or distant. If the woman has many roles to fulfil, she may be torn between the roles she is comfortable with and those which she finds difficult. Equally, a woman’s expectations of pregnancy and childbirth will affect how she sees herself in each given situation; does she see herself in control, responding to the changes which happen day by day, or does she see herself out of control, fearful and/or angry? Asking women these questions, and discussing them, may help the midwife see whether a woman has a realistic view of pregnancy and childbirth.

Family relationships

The woman’s relationship with her partner may come under pressure, particularly if the partner feels left out. It is at this time that domestic abuse may present for the first time as the partner becomes insecure and feels jealous (see Chapters 19 and 23). The midwife needs to be observant for signs of such abuse. Finances may become strained as the woman leaves work, even if this is temporary, and this can affect their relationship.

Becoming a parent for the first time challenges a woman’s resources:

The midwife can help her make an assessment of the above with suggestions regarding how and where further resources may be found.

Adapting to pregnancy

For some women, this comes naturally; they seem to go with the flow, blooming with health and relishing their pregnancy, not getting upset. Raphael-Leff (1991) referred to these women as facilitators. Others find pregnancy more difficult: the woman feels irked by the fact she is pregnant; it is an inconvenience. These women are referred to as regulators, and may resist the loss of control which pregnancy brings.

Psychological health during pregnancy

During the first visit in pregnancy at which a history is taken, midwives should try to identify the woman’s perceptions of her mental health. It is also important to identify whether the woman has experienced any previous mental health issue (see Chapter 69). If the midwife has begun to develop a relationship or rapport with the woman, then it is easier to ask this question. If no rapport or relationship exists, then a woman may be loath to disclose this information for fear of stigma or rejection by the midwife.

In the last Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (Lewis 2007) the most common cause of indirect deaths and the largest cause of maternal deaths overall was psychiatric illness (for further details, see Chapter 69). It is therefore important to recognize when a woman is mentally ill.

When assessing a woman’s psychological health, it is important to establish the following:

If the woman answers yes to the last two points, it is important to refer her back to her general practitioner for further assessment and support, or to a midwife specialist who will be able to undertake more detailed assessment (see Chapter 69). The general practitioner must be kept informed of any care provided, and the care written in the woman’s notes.

Reflective activity 12.3

When next taking a history from a woman, reflect whether a comprehensive and detailed history of psychological health was taken, using the above text as a checklist.

Access to counselling in some NHS trusts can be limited. Referral needs to be fast-tracked; or if a woman’s mental illness is considered to be mild, such as a mild depression, she can be advised about self-help approaches such as relaxation techniques, or guided imagery to focus on the positive aspects of her life (see Chapter 69 for more serious situations).

Each NHS trust should have a clinical network which provides perinatal mental health services so that women receive the care most appropriate for them (NICE 2007) and midwives must be aware to whom they would refer a woman for the most appropriate care.

Psychological aspects of caesarean section

The caesarean section rate at an urban hospital known by the author in 1978 was 13%, spontaneous births 80% and instrumental births 7%. In London teaching hospitals at the same time the caesarean section rate was 20%. Birth was no more or no less dangerous than it is today; however, women’s belief in their ability to give birth has decreased and the request for elective caesarean sections has increased. Along with this self-doubt is the fear of the pain that is to be experienced or the damage that may be caused by a vaginal birth (see website for Case scenario 12.3).

Women who request birth by caesarean section may be:

It would be useful for both these women to be referred to a midwife who specializes in counselling and/or be offered psychotherapy with women or encouraged to meet and speak with those who are able to speak of enjoyable birth experiences (see website for Case scenario 12.3). In addition, women who have had a baby born by caesarean section often need the opportunity to reflect upon their labours. If a woman’s baby has been born by emergency caesarean section following a few hours in labour with analgesia, she may not be able to remember events clearly. This means she will feel confused and result in her feeling traumatized. She may not have been able to read the non-verbal communication because of her tiredness and the analgesia received; her hearing may have been affected and she may not be able to remember having been told certain information. If this has happened, she may feel very frightened because she felt so out of control and angry as it seemed that no-one spoke to her at the time.

Offering a woman the opportunity to see her notes and discuss this with the midwife who cared for her for the longest period of time so that she may go through the records of her labour will assist in making sense of what has happened. This may decrease her confusion and therefore her anger to help her become calm enough to sleep and also to care for her baby (Smith & Mitchell 1996).

When words such as ‘Caesarean section for failure to progress’ have been written in the notes (or spoken), a woman is left feeling a failure. She, therefore, begins her parenting/mothering career in a negative mood. This mood can be difficult to shift and self-doubt (which can be confused with depression) can set in, leading to increased anxiety. This will affect the flow of breast milk and thus her ability to feed her baby.

When working through the notes it is important to praise the woman so that she is able to see how well she did and that she did not fail in any way. We need to remember that people require five portions of praise to counterbalance one portion of criticism. This is important not only in our work with women but also with our colleagues. When giving feedback to our students or colleagues we need to remember to balance praise with criticism, because midwives can feel disappointed or a failure when births do not go as expected. Therefore, all women and midwives need appropriate support offered to them by their peers or by supervisors of midwives (Lewis 2004).

Post birth, the early days of motherhood

A woman’s first experience of contact with her baby will differ according to how she has experienced her pregnancy and her birth and her personal expectations. Some women experience relief, joy, with overwhelming love. Others will experience shock; as the baby will not match the fantasy picture created in their mind:

All of these experiences are normal, and the way the midwife interacts with the woman will enable expression of these thoughts and feelings so as to adjust to motherhood. It is when a woman is unable to express her thoughts and feelings that she remains anxious and therefore unsettled, unable to enjoy her baby and get to know him or her, and, most importantly, to sleep. Sleep is a great healer and enables the body and mind to recuperate and re-create itself. Sleep deprivation may lead to irritability, tearfulness, tension, anxiety and self-doubt.

At some point in the first 24 hours, the woman and her partner will explore the baby, looking for familial similarities. If a woman is frightened to do this, the midwife needs to assist her in this meeting with her baby. This is usually more successful when the baby is awake and alert, therefore responsive to the parents smiling and crooning. If possible, this meeting is best undertaken within a short period following the birth so that breastfeeding may be initiated. As the midwife is more likely to recognize a baby communicating the desire to feed, she needs, in a warm positive tone of voice, to point out the signs when the baby is looking for mummy to feed him or her, whatever method of feeding has been chosen. The woman can then recognize the signs in the future. In this way, the woman will not feel that she lacks experience. If the woman has chosen to breastfeed, explain to her before she offers the breast to the baby, that she needs to be physically comfortable. Also, demonstrate how to recognize when baby is in the correct feeding position. This will increase a woman’s confidence and her ability to breastfeed her baby successfully. Explain that baby will learn along with her, but that all babies have an instinct to suckle.

A quiet period following the birth allows the stress hormones activated in labour to recede and settle, enabling anxiety and fear to decrease so that a woman and her partner may celebrate their success together. This settling often enables the woman to look back on her birth experience with satisfaction as it enables her to regain her control. If this quiet period is missing after a birth, a woman’s agitation is likely to increase with the sense of being out of control. This will occur especially when a woman is hurried out of a birthing room because the delivery suite is busy and her bed is needed.

If this does happen, the midwife needs to ensure that wherever the mother is moved, she and her partner are able to have quiet time together. This often means protecting women from initial visits from relatives or friends. This may result in the midwife being unpopular, but the woman, partner and baby come first.

Baby in the neonatal unit

When a baby is ill and has been removed to a neonatal unit, the woman must be able to see photographs or a digital recording of her baby. A visit, as soon as possible, is also important, by the mother or by her partner, who will report back, or by both together, so that they may see, touch or even hold the baby; as this will reassure parents that the baby is alive and beginning to thrive, which assists in reducing the trauma of the separation (Robinson 2002).

The woman and her partner will need clear explanations of the care and any reasons for plans in caring for the baby. The explanations may have to be repeated or written down so that parents may grasp what has happened. Their anxiety may interfere with their ability to absorb information. If women are separated from their babies, regular updates need to be given for them to understand what is happening and have some control over the situation.

If a woman shows no interest in her baby, this needs to be noted, but not acted upon straight away. The midwife needs to continue offering support to the woman and speaking of the baby as she would with a woman who is besotted with her baby. Most women in this situation adjust and begin to show an interest within 24 to 48 hours of the birth. If the woman continues to express little or no interest in her baby after this period of time, it is important to liaise with the woman’s health visitor so that the woman receives extra support on her transfer home.

During the first few weeks following the birth the woman and her family will need to make adjustments to their relationships and the way they live. Most women are surprised by the amount of time it takes to care for a newborn baby. Women may express their dismay when their baby does not feed and sleep for 4 hours, thus allowing them to get on with household chores. The baby may not sleep throughout the night and women will have to get up and feed baby, often three or four times a night, thus they experience sleep deprivation. Resentment is often experienced towards the partner who may have persuaded the woman to artificially feed the baby because, ‘Then I will be able to feed baby during the night and take my turn.’ Whilst this is often a naïve belief, the partner may have been truthful when expressing this statement, but may not have had any previous experience of life with a baby. If the partner has to return to work immediately following the birth and is expected to be out of the house by early morning and does not return until late evening, it is unlikely that the partner will be able to assist with night feeds. The demands of the daily work routine combined with a disturbed sleep pattern may lead to sleep deprivation causing stress to both parents. It is important for midwives to explore the reality of new parenthood at some point with women and their partners.

Physiological event

Though promotion of birth as a normal physiological event is ideal, it is important to recognize it is a strenuous event. Women used to remain in hospital recuperating from the birth for a period of 10 days, but they now return home within 6 to 48 hours after birth. This is appropriate as the family can begin to make the adjustments required to accept the baby into the home.

Many women have support at home for a week whilst the partner has parental leave. Given that the woman has probably been in hospital for a very limited period of time or had her baby at home, she is likely to be tired from the birth.

In some cultures, women are supported by other female family members for up to 6 weeks. If an aunt or sister is able to move into the house to take over the household chores whilst the woman focuses on mothering her baby and greeting her partner at the end of the day, this is to be welcomed and celebrated. If this is not possible, then encourage the new family to ask friends and family for practical support such as some housework or a cooked meal. A midwife who explains carefully to the woman about increasing her activities slowly, is offering good advice; often women attempt to return to ‘normal’ too soon and end up being tired or developing mild postnatal depression because they cannot live up to their own high expectations.

Conclusion

The journey from conception through pregnancy, childbirth and early parenting is full of immense change in every aspect of a woman’s life. It is a time when a woman is at her most creative and during this creativity she has the right to have midwives who are able to support her to achieve a safe, normal pregnancy and labour that is as happy and enjoyable as possible. The midwife is the health professional who is able to support the woman on her journey and to offer holistic care which takes into account the psychological aspects of the childbearing journey.