Chapter 23 Vulnerable women

After reading this chapter, you will:

Introduction

Women who find themselves disadvantaged may have multiple social needs that affect their uptake and use of maternity services (DH 2007a). This chapter will provide an overview of the particular needs of these women and some introductory pointers to raise awareness and ensure that the most vulnerable women and those with chaotic lifestyles receive appropriate maternity care. The UK National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services, Standard 11 champions the importance of inclusive maternity services (DH 2004a).

Domestic abuse

Domestic abuse can be defined as:

‘Any incident of threatening behaviour, violence or abuse (psychological, physical, sexual, financial or emotional) between adults who are or have been intimate partners, or family members; regardless of gender, sexuality, disability, race or religion.’

(BMA 2007:1)

The term domestic abuse also includes a number of issues more prevalent in minority ethnic groups, such as forced marriage, female genital mutilation/cutting and ‘honour crimes’.

Key facts

Domestic abuse is underreported, mostly due to fear of reprisal, stigma and a continued relationship with the perpetrator, therefore any statistical data need to be interpreted with caution.

Domestic abuse is a major public health issue as during pregnancy it may result in direct harm to the pregnancy, such as preterm birth (Newberger et al 1992) antepartum haemorrhage and perinatal death (Janssen et al 2003), and also indirect harm through a woman’s inability to access antenatal care (NICE 2008). Domestic abuse has long-term consequences upon a woman’s mental health, with increased likelihood of the victim suffering from anxiety, depression and psychosomatic symptoms (BMA 2007).

A number of professional and governmental bodies, including the Royal College of Midwives (RCM 1999), the British Medical Association (BMA 2007), the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG 1997) and the Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCPsych 2002), advocate that all pregnant women should be asked about domestic abuse. This should form part of the needs, risk and choice assessment at the booking visit. Suggested questions include:

The process of routine enquiry for domestic abuse has been shown to be acceptable to women (Ramsay et al 2002). By asking all women and explaining it is a routine question, it helps to destigmatize domestic abuse and it also gives ‘permission’ for the woman to disclose at this time or at a later date.

All women, regardless of disclosure, should be provided with information and contact helplines for support and advice. Where a partner or other person is present, the question should be asked at a later date or an excuse found for the midwife to talk to the woman alone. In situations where a woman does not speak English, the question should be asked through an interpreter and not a family friend or relative. Where possible, the interpreter should be female and have received some instruction on domestic abuse.

A midwife’s role is to let the woman know that she can disclose if and when she is ready. The midwife should refer on and not act as a caseworker for the woman.

It is important that a woman reaches her own decision about what to do. It may be that the woman:

Midwives need to be vigilant and sensitive to possible indicators of domestic abuse, including:

Documentation of the issues or concerns is imperative, but this should not be in the handheld notes. Confidentiality is important, but, where there is multi-professional working, it is important that information is shared. There are limits to confidentiality. If there are reasons to suspect children are at risk, safeguarding and protection takes precedence. This needs to be explained to the woman.

The Home Office guidance (Taket 2004) recommends the following mnemonic to aid the approach:

Drug and alcohol misuse

The risks of physical, psychological and social harm for women who have significant problems related to alcohol and drug use during pregnancy are well documented (DH 2007b). It is also potentially harmful for the baby. Whilst the risks associated with smoking during pregnancy are also recognized, they are not covered in this chapter (see Chapter 19). There are a number of illicit substances used by women in pregnancy, including cocaine, heroin, cannabis and benzodiazepines. Poly-substance misuse – for example, opiates and alcohol – is not uncommon (Lewis 2007).

Substance misuse is often compounded by other factors, such as poverty, social exclusion and homelessness (Kaltenbach & Finnegan 1997). Pregnant drug-using women are therefore at increased risk of poorer general health and other health-related problems, including bloodborne viruses, such as hepatitis B and C. They should be cared for as part of a wider integrated multi-professional team which includes addiction, neonatal and social services.

Substance misuse during pregnancy increases the risk of poor pregnancy and newborn outcomes (DoH 2007b), including:

Midwives should be alert to the fact that substance misuse may be associated with past or current experiences of abuse and with psychiatric or psychological problems (Klee 1997).

Antenatal care

Substance misuse makes a significant contribution to maternal mortality, with 11% of all pregnant women who died between 2003 and 2005 having alcohol or drug problems (Lewis 2007). Women often book late. This may be owing to a number of issues, including chaotic lifestyles, poor service accessibility, fear of being judged, and avoidance of social services (Lewis 2007). The booking history should include sensitive routine enquiry about all substance misuse; this includes the use of alcohol, tobacco, prescribed or non-prescribed and legal and illegal drugs. However, for some women, pregnancy may act as a positive incentive to change substance-misusing behaviour.

If it emerges that a woman has a problem with drug or alcohol misuse, she should be encouraged to attend addiction services, or specialist maternity services where available. Antenatal services should arrange a multi-professional assessment of the extent of the woman’s substance use, including type of drugs, level, frequency, pattern, and method of administration, and consider any potential risks to her unborn child from current or previous drug use.

Intrapartum care

Routine care during labour should be provided, with careful observation of mother and fetus for signs of withdrawal. Commonly seen symptoms in the mother include restlessness, tremors, sweating, abdominal pain, cramps, anxiety and vomiting. In addition, the fetus is at increased risk of hypoxia and fetal distress, as the effects of drug misuse can cause placental insufficiency (DH 2007b).

Postnatal care

All mothers and babies should be transferred to the postnatal ward unless there is a medical reason for admission to the special care baby unit. Breastfeeding should be promoted where possible; however, this is contraindicated if the woman is:

Neonatal abstinence syndrome (withdrawal symptoms) occurs in 55–94% of neonates exposed to opiates in utero (American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs 1998). Commonly seen symptoms include sneezing, poor feeding, irritability, high-pitched cry and tremors (Shaw & McIvor 1995). Hyperphagia can also occur, usually associated with weight loss, but occasionally with excessive weight gain (Shephard et al 2002).

Close follow-up and multi-agency support to keep women in treatment programmes is essential; this is particularly significant if the baby is removed from the woman. Relapse can be a problem and the latest Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH) report highlighted that a majority of women who died with known alcohol or drug misuse problems did so after 42 days postnatally (Lewis 2007).

Safeguarding children

It is estimated that there are between 250,000 and 350,000 children of problem drug users in the UK (Home Office 2003), representing 2–3% of children under the age of 16 in England and Wales (Lewis 2007). Midwives and addiction services need to be aware of the laws and issues that relate to child protection. If they have any concerns, they must contact their designated named lead for child protection, supervisor of midwives or social services for advice.

Reflective activity 23.2

At the booking visit, a woman who works as a barrister tells the midwife that she used to smoke cannabis but stopped when she discovered she was pregnant. She subsequently misses two antenatal appointments. When you ring her to find out why, she states that she has been extremely busy at work. She is quite dominant in her personality and promises you that she will attend the next appointment. She doesn’t. What action would you take?

Teenage pregnancy

In June 1999 the Social Exclusion Unit produced a report on teenage pregnancy and parenthood (see Ch. 13). The report highlighted two main goals:

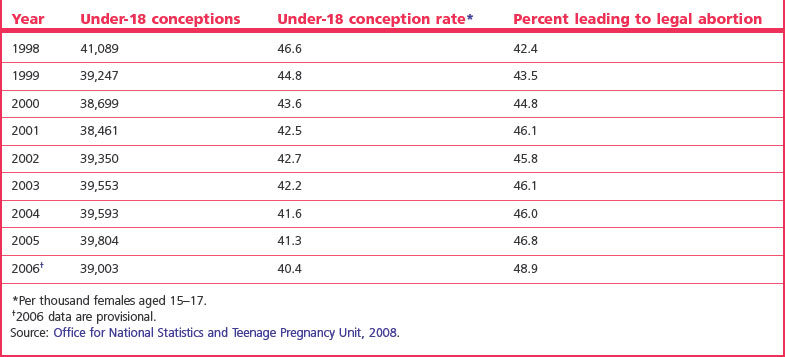

The provisional 2006 under-18 conception rate for England of 40.4 per 1000 girls aged 15–17 represents an overall decline of 13.3% since 1998, the baseline year for the Teenage Pregnancy Strategy (ONS 2008; see Table 23.1). The under-18 conception rate is now at its lowest level for over 20 years; however, it is still one of the highest in Western Europe, with approximately 90,000 teenagers becoming pregnant annually (DCSF 2008). Poorest areas of the country are most affected.

It is recognized that becoming a teenage mother can have negative consequences on a woman’s physical and mental health and limits social and educational opportunities, which may impact on future economic wellbeing (DfES 2006). Children born to teenagers are more likely to have poorer health and social outcomes in later life (Swann et al 2003) and daughters are more likely to become teenage mothers themselves (Berrington et al 2005).

Effects on child health

Effects on economic wellbeing

A number of key areas have been identified which can make a difference in reducing teenage pregnancy rates and therefore limit the negative health impact that is associated with it:

Black, minority and ethnic women

Population movements worldwide have resulted in changes to the profile of women using NHS maternity services. The number of people from black and minority ethnic (BME) communities in Great Britain is increasing (CHAI 2008).

There is a strong association between ethnicity, deprivation and poor outcomes in maternity care (Lewis 2007). There is a higher risk of infant death for babies born to mothers from East or West Africa and the Caribbean (London Health Observatory 2007). The Bangladeshi and Pakistani groups make up a four-times larger proportion of the population in the most deprived areas and for black Caribbean and black African groups the proportion is two-and-a-half times higher (DH 2007c).

The arrival of new communities, primarily from the enlarged European Union, has also increased demand on maternity services (Darzi 2007, 2008). These groups share some common characteristics:

Migrants are not a homogenous group and can be divided into the following:

Recently arrived asylum seekers and women with no recourse to public funds are likely to be more vulnerable than people who have come for employment (Taylor & Newall 2008).

Reflective activity 23.3

A 17-year-old Chinese woman, Chew Yeen, attends your booking clinic. She is an hour late for the appointment and tells you in broken English that she walked to the appointment but got lost. She is accompanied by a friend who only speaks Cantonese. From your assessment, you think she is about 28 weeks pregnant. She repeatedly tells you, ‘Everything is fine, no problem’. How would you meet the needs of this woman?

Asylum seekers and refugees

Background and definitions

The 1951 Refugee Convention (UNHCR 1951) defines a refugee as:

‘any person who … owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his (or her) nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself (or herself) of the protection of that country’.

An asylum seeker is defined as:

‘a person who has left their country of origin and has applied for refugee status in another country and is waiting for the decision’ (UNHCR 1951).

The term ‘failed’ asylum seeker is used to describe people who have had their asylum claims refused, who have lost their appeals and who have reached the end of the process (Bennett et al 2007).

Pregnant women who have been displaced from their country of origin may have a number of key issues in common:

Asylum seekers from some countries may have additional health needs; for example, women born in sub-Saharan Africa are disproportionately affected by HIV (Health Protection Agency 2008). Women from some countries, for example Somalia and Sudan, may have undergone female genital cutting (Powell et al 2002).

Although there are some examples of good practice in designing maternity services to meet asylum seekers’ needs, many asylum seekers find it difficult to access care (Gaudion & Allotey 2008; Harris et al 2006; Project London 2007, 2008). Access to services is made more difficult because of transience of residence, relative poverty and uncertainty within a complicated asylum process (see website for video: Florence … the experience of becoming a mother in exile).

Evidence in the latest CEMACH report demonstrates that the care provided for women who are seeking asylum in the UK does not always provide for their needs; for example, black African women, including asylum seekers and newly arrived refugees, have a mortality rate nearly six times higher than their white counterparts (Lewis 2007). The report highlights that this may reflect not only cultural factors implied in ethnicity but also social circumstance. Significantly, the report recognized that for this group of women there may be additional risk factors, including poor overall health status and underlying and possible unrecognized medical conditions, such as cardiac disease.

Teenagers who are seeking asylum are particularly vulnerable because of their situation; living in poverty with uncertainty and because of a lack of familial support and a lack of experience inherent in their youth (Gaudion & Allotey 2008).

Access to maternity services

Accessing services by women who are not well integrated into a community is challenging simply because of the principle ‘you do not know what you do not know’ (Gaudion et al 2007a; Homeyard & Gaudion 2008). There is little information in the public domain about how to access services (Fig. 23.1; Gaudion et al 2007b) (see website). Current and changing entitlement to NHS maternity care has led to another potential barrier to accessing antenatal care. The Department of Health guidance states that women should be given access to care (DH 2004a); however, the way this is implemented varies between hospitals. The request for payment for care from newly arrived migrants may not come as a surprise for them as they may have arrived from countries where antenatal and intrapartum care is routinely purchased.

Confusion over the 2004 regulations regarding entitlement to NHS care has impacted on access to care for some women (Kelly & Stevenson 2006). The guidelines for Entitlement to Health Care are under review but they currently state that maternity care is classed as immediately necessary care. This means that all antenatal, birth and postnatal care should be provided irrespective of ability to pay (DH 2004b).

Language

Caring for women whose main language is not English can present problems for staff (CHAI 2008). It is of particular concern as it may lead to women receiving suboptimal care because:

It is important to remember that women may have a basic working knowledge of the English language that enables them to go shopping or catch a bus but this does not mean that they will have the vocabulary to fully understand issues around antenatal screening or understand the relevance of their past medical and obstetric history on their current pregnancy. In the latest CEMACH report, 48 of the women who died spoke little or no English (Lewis 2007).

The National Service Framework stipulates that all NHS maternity providers should have an interpreting and advocacy service (DH 2004a). Additional solutions may include having staff who speak commonly used languages, access to a language line and translation of commonly used maternity information publications (CHAI 2008). A recent needs assessment conducted at Brunel University on asylum seekers in maternity services found:

Gypsy, Roma and Traveller women

Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities are the largest ethnic minority group in Europe. The Commission for Racial Equality (2006) estimated that there were approximately 200,000 to 300,000 people in the UK. They are also the most marginalized and comprise a number of different ethnic groups. Sensitive targeted outreach services to enable women to access and use maternity services is important. A study at Sheffield University found that these women have a higher rate of miscarriage, stillbirth and infant death (Parry et al 2004).

Travellers and Gypsy women may have difficulty accessing maternity services for a number of reasons:

Within the Traveller and Gypsy community, women marry young and having children is an important part of their cultural identity. ‘Mochadi’, a term used to describe cultural issues of cleanliness and modesty, are important. The functions of cleanliness include all activities from washing, food preparation, and relationships. Washing hands is particularly important, especially before handling food and in the morning after getting dressed.

Women’s issues are not discussed when men are present, including pregnancy. Although women should be offered the option of their husbands accompanying them at the birth, it should be recognized that this is not the norm for them. Childbirth is ‘understood’ as polluting and therefore best away from the home and in a hospital. This is a way of limiting the effects of the contamination of the process (Okley 1983). Privacy and modesty also affects uptake of breastfeeding, as women do not like to ‘expose’ their breasts in public or even on-site where their husbands or other men might see them. Some Traveller and Gypsy women may prefer not to be cared for by a male health professional.

Improving service provision for Gypsy, Roma and Traveller women needs to include designing a flexible service near the site, if not on-site; a system so that women can directly access a midwife and that when they move, the midwife can ring ahead and arrange ongoing care.

Poverty and destitution

Research has shown that as poverty increases there is a corresponding increase in infant deaths (DH 2007a). Reducing infant mortality and increasing life expectancy are a Government priority. The infant mortality part of the Public Service Agreement states that ‘starting with children under one year, by 2010 to reduce by at least 10% the gap in mortality between the routine and manual group and the population as a whole’ (DH 2007d).

The ‘routine and manual group’ includes people working in lower supervisory or technical jobs, semi-routine and routine occupations, for example, cleaners, bar staff/waitress, shop assistants, train or bus drivers, sewing machinists, plumbers and people working in call centres (DoH 2007d).

A third of all the women whose deaths were investigated in the last CEMACH report were either single or unemployed or in a relationship where both partners were not employed. In England, women who lived in the most deprived areas were five times more likely to die than women living in the least deprived areas (Lewis 2007).

In the UK there are a number of factors that can make a woman destitute, including:

Women who have no recourse to public funds are particularly vulnerable, not just in terms of healthcare but the whole remit of social provision for themselves and their children. They have limited options; although some basic support (Section 4 support) may be possible, it is often linked, for ‘failed’ asylum seekers, to being returned to their country of origin (Home Office 2007). Other options include voluntary return, support from local authorities under Section 21 of the National Assistance Act 1948, Section 17 of the Children Act 1989 or Section 117 of the Mental Health Act 1995 (Taylor & Newall 2008).

Conclusion

Meeting the challenges of maternity service provision for women who are, because of age, ethnicity, immigration status or social situation, more vulnerable, is not easy. None of the groups discussed are homogenous; every woman is an individual and may ‘fall’ into more than one of the above categories. Each individual woman presents from a different culture, ethnicity, religion, identity, family structure and educational background; each with unique life experiences that inform their interpretation of and uptake of maternity services. Their needs are correspondingly diverse.

The central most important issue is communication; no midwife or other health professional should work in a silo, and information sharing is crucial. It is not necessarily about specialist services but treating women as individuals and being able to signpost to services that are specialized in order to maximize outcomes for mother and baby. Good practice in maternity care can help build the necessary early links with women and families and ensure that agencies are in place so that they all work together to provide a coherent and responsive service. With complex cases, it is important to consult with the supervisor of midwives, who can offer advice and support.