Chapter 19 Health promotion and education

Introduction

The importance of the health promotion role of the midwife within the context of health and healthcare provision in the 21st century is crucial in enhancing the health and wellbeing of women and their families. There is potential for developing health gain through utilizing midwifery skills in practice. The notion of health promotion is explored, enabling readers to develop firm foundations for effectively progressing their work in midwifery and their wider public health role.

The meaning of health

Health is a state of being to which most people aspire, yet a concept difficult to define, as personal meanings are enshrined in social structure, culture and belief systems. In 1946, the World Health Organization (WHO) described health as a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing, not merely the absence of disease or infirmity (WHO 1946). Health is thus seen as an ideal state of being which may be impossible to achieve. In an attempt to clarify the meaning of health, Seedhouse (1997) suggests that health is determined by the individual’s socioeconomic and cultural position, the context of which is determined by biological or chosen health potentials that provide an opportunity for the individual to aspire to achieve good health within the context of that health potential.

Reflective activity 19.1

What does being healthy mean to you? Jot down your personal definition of ‘being healthy’.

Lifestyle behaviours, personal habits and personal constructs of the health of individuals are major contributors to health and illness. These may be affected by the individual’s attitudes and beliefs, culture, ethnicity, social class, religion, gender and economic status. It is crucial, therefore, that health professionals are aware of their own attitudes, beliefs and personal constructs of health prior to promoting the health of others.

Health is to be viewed holistically, involving dimensions of health that are inextricably linked and include physical, mental, emotional, societal, sexual and spiritual health. If one dimension is negatively affected, this will have an impact on other dimensions (Ewles & Simnett 2003).

Models of health

Health models have been developed to try to explain why some individuals indulge in healthy behaviours and others do not. Well-known models include the Health Belief Model, formulated by Rosenstock in the 1960s and developed by Becker in the 1970s (Becker et al 1977), which was specifically designed to explain and predict preventive health behaviours. The Health Locus of Control, proposed by Rotter (1966), refers to the personal control over events that people believe they possess and is commonly used to explore how people’s beliefs about health and illness affect their behaviour. More information is available in the references and the website.

Reducing inequalities in health

Understanding the social, cultural and economic context of health and illness increases the opportunity for health promotion to be meaningful and effective. Poverty and deprivation are linked to poor health outcomes (Lewis 2007). In the UK, the National Health Service (NHS) was set up in 1948 to provide free medical care to the whole population and thereby achieve equality of access to health services for those in need. The hope was this would eliminate or greatly reduce inequalities in health. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this single approach to improving the health of those worst off in society did not succeed. The provision of health services cannot singularly solve inequality in health without addressing factors that influence ill health. Even when health improvements are made for all, inequalities continue to persist. Health inequalities are linked to wider determinants including income, housing, education and other opportunities which must be tackled so that health interventions can be effective (Office for National Statistics 2007).

A commitment to improve healthcare for all

Over the last three decades, a plethora of policy documents and guidance regarding health inequalities with ways of reducing these in tandem with healthcare provision have been published. The following documents present a useful insight into policy and guidance:

Some, such as the Black Report, demonstrate substantial differences in mortality and morbidity rates between social class groups and made recommendations to address this (Black et al 1982) though these were not endorsed.

What is health promotion?

WHO defines health promotion as the process of enabling people to increase control over their health, and improve it. Integral to this definition is the notion of empowerment (WHO 1984). An example of empowerment in midwifery practice is the process by which the health professional uses strategies to enable the woman and her partner to lead and take control over their childbirth experience, resulting in development of personal empowerment, skills and control in everyday life.

The midwife’s role encompasses a wide range of health promotion initiatives that may not influence immediate behaviour change, including advice and guidance about baby care and parenting. Decision-making, empowerment, debriefing and health education are important for health promotion in midwifery and should be provided throughout the antenatal, labour and postnatal period, as a coherent whole, rather than an activity placed within an antenatal education class.

Health develops by an ongoing relationship between the individual and their environment (Bauer et al 2006). The ultimate aim of health promotion is to provide opportunities for people to move within the context of their biological, intellectual and/or emotional potential (Seedhouse 1997). The momentum of movement, or indeed its maintenance, is likely to be successful only if the most appropriate avenue has been chosen to promote health, that is particular to or within the context of an individual’s life. A realistic approach to health promotion would include assessing the context of the woman’s living experience and identifying with the woman obstacles that inhibit the fulfilment of health potentials (see website for Case scenario 19.1).

Mental health promotion

Impaired mental health has a negative impact on emotional and physical health and reduces the individual’s capacity to cope with everyday life activities. The process and impact of postnatal depression is one example of how physical, spiritual, emotional and mental health are affected (see Chapter 69).

Sexual health promotion

Addressing sexual health issues may contribute to the overall wellbeing of the woman and family, therefore the midwife has an important role to play in this area of public health (see Chapter 57).

Sexuality and pregnancy

Sexuality is influenced by health, personal circumstances, self-image and self-esteem. Physical, mental and emotional health influence how individuals view their own sexuality. Pregnancy, childbirth and motherhood challenge personal concepts of sexuality and sexual expression, though the impact of physiological and psychological changes that occur during pregnancy is generally beyond personal control. For example, physiological effects of pregnancy, including pelvic vasocongestion resulting from increasing levels of the hormones oestrogen and progesterone; changes in body image; or ‘minor disorders’, such as vulval varicosities and haemorrhoids, may change a woman’s sexual experiences.

Sexuality in pregnancy is an important aspect of health that is not always addressed appropriately. Some women may feel embarrassed broaching this topic and some midwives, fearing intrusion of privacy, may also be reticent about discussing the issue. There may be religious, cultural and social taboos about having sexual intercourse during pregnancy, but some couples may have anxieties that could be relieved through frank discussion (see Chapter 13).

A health promotion model

A model may be described as a conceptual framework for organizing and integrating information offering causal links among a set of concepts believed to be related to a particular problem (Seedhouse 1997). There are several health promotion models that assist the practitioner in undertaking health promotion work. Here, only one model will be presented and explored in detail.

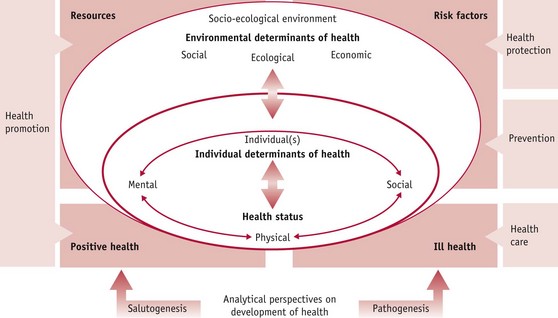

The health development model (Bauer et al 2006) in Figure 19.1 shows that health development is an ongoing process and health promotion intentional and planned. The model identifies three dimensions of health: physical, mental and social, and shows the interrelationship between health promotion and public health. The arrows pointing between these dimensions show that they are interdependent and interrelated. For example, exercising during pregnancy positively influences mental health and enables interaction and communication with others, thereby supporting social health.

This model shows the central role of salutogenesis and pathogenesis, which is integral within health and the health promotion process, illustrating that health development is an ongoing process, and health promotion is an intentional and planned approach aiming to sustain change within the health development process.

When using the model it is useful to note that the health of an individual is not created and lived in isolation but results from a dynamic ongoing relationship with the relevant socio-ecological environment, including the cultural dimension (Bauer et al 2006). The health promotion approach taken must therefore reflect this. The model also identifies that an individual’s health status determines future health, and can be used as a predictor of health; however, a targeted health promotion approach can improve the health potential of that individual. For example, a mother who smokes may be helped to stop smoking during pregnancy and therefore enhance her life potential and that of her baby.

The majority of studies that set out to establish the determinants of health and ill health are set within the pathogenic paradigm (Tones & Green 2004). Pathogenesis analyses how risk factors of individuals and their environment lead to ill health. Antonovsky (1996) proposed that an additional perspective should be adopted by health promotion practitioners, that of salutogenesis, which examines how resources in human life support development towards positive health. Bauer et al (2006) suggest that in real life, salutogenesis and pathogenesis are simultaneous, complementary and interacting real-life processes.

Health promotion approaches

A health promotion approach can be described as the vehicle used to achieve the desired aim. An example would be the aim of raising awareness about the efficacy of vitamin K. The ultimate objective may be to enable the woman and her partner to make an informed choice about its use, but the health promotion approach may vary according to the woman, practitioner and context.

Ewles & Simnett (2003) identify five health promotion approaches:

Box 19.1

Health promotion in practice

Medical approach

Seeks to prevent and/or cure illness through medical intervention.

Example: the midwife may offer the woman who is non-immune to rubella the vaccination in the postnatal period and contraceptive advice for a period of 3 months. Education and discussion should form part of this process. Didactic instruction should be avoided.

Behavioural change approach

Primary focus is on encouraging people to change their behaviour.

Example: dietary adjustment to include more fruit and vegetables. This may involve raising awareness through education, empowerment and decision-making. Client-centred work should form part of this strategy to ensure success.

Educational approach

Provision of information, tailored to meet the individual needs of the client.

Example: this approach is generally a precursor for other approaches. Methods that will enhance the educational approach include group work, discussion methods and problem-solving.

Client-centred approach

This places the client at the centre of an interaction that is based on an equal partnership between the client and the professional. Empowerment is integral to this approach where individuals are encouraged to utilize personal strength toward health gain.

Example: making an informed decision about the uptake of antenatal screening tests, and behaviour change including stopping smoking.

Societal change approach

Health promotion initiatives are focused on societal health and involve, for example, policy planning and political action (Dunkley 2000).

Example: political and community action toward the prohibition of smoking in enclosed public spaces and workplaces.

Health promotion – community action

Health enhancement through community initiatives is well supported (DH 2008b). Health promotion has the potential to influence the health of present and future generations, with scope for a profound impact on reducing inequalities in health. Antenatal and postnatal care is predominantly provided in the community (historically recognized as a key arena to address these issues) where care is accessible with opportunity for flexibility at the point of delivery. Sure Start Children’s Centres provide a multi-agency, multidisciplinary focus to healthcare provision, located in the heart of the community, focusing services toward vulnerable women and their families.

The aim of Children’s Centres is to improve the health and wellbeing of children and their families through achieving health and reducing inequalities.

They bring together childcare, health, family support and early education to improve access to services. It is commonplace to have midwives based in Children’s Centres providing maternity care within a multi-agency family-focused setting. With additional support from maternity services, midwives have the potential to develop services in areas where they have the greatest reach, including supermarkets, community centres and mobile bus services. Healthcare provision in an environment outside of the hospital setting increases opportunities for developing equal partnerships between midwives and women – reducing the potential for medical dominance and power.

Although traditionally midwives have provided postnatal care up until 28 days postpartum, the National Childbirth Trust found that women reported they had insufficient help and information between 11 to 30 days after birth, compared with the first 10 days (DH 2004). The National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services, Standard 11 (DH 2004) suggests that midwifery-led services should be provided for the mother and her baby for at least a month after birth or discharge from hospital, and up to three months or longer depending on individual need.

This is a time when most families may be more receptive to health promotion, particularly with a new baby at home. The Royal College of Midwives (RCM) emphasizes the strength of midwifery within the community setting, encouraging the development of the midwife’s public health role (RCM 2000, 2001).

Provision of maternity care to members of the travelling community and immigrant families presents challenges to the midwife’s role in relation to equality and access to healthcare provision and services. Eviction orders, commonly associated with the travelling community owing to unlawful caravan parking, cause disruption in midwifery care provision. Local authorities proceeding with eviction orders are required to liaise with the relevant statutory agencies, to enable practitioners to fulfil statutory obligations, particularly where pregnant women and neonates are involved.

In 2007, asylum seeker applications in the UK totalled 23,430 (including dependants) (Home Office 2007). The Reproductive Health for Refugees Consortium made recommendations which included the need for culturally sensitive reproductive health, and appropriate referral systems, should obstetric emergencies arise. The health of pregnant asylum seekers is frequently compromised by lack of antenatal care, stressful, tortuous journeys from countries of origin, turmoil caused by war, oppression and poor nutrition. Their health disadvantage increases the risk of perinatal mortality and morbidity (Lewis 2007) and renders them ill-prepared for childbirth and parenting, particularly if antenatal care has been sparse (see Chapter 23).

It is for this reason that all pregnant mothers from countries where women may experience poorer overall general health, and who have not previously had a full medical examination in the UK, should have a medical history taken and clinical assessment made of their overall health by their obstetrician or GP (Lewis 2007). In particular, female asylum seekers arriving in the UK from certain countries in Africa and the Middle East may have undergone female genital mutilation (FGM) and as such require sensitive history-taking to ensure that an appropriate care plan is developed for pregnancy, labour and the postnatal period (see Chapter 58).

Preconception care

Preconception care is described as the ‘passport’ to positive health during pregnancy. The aim of care is to optimize the chances of conception, ensure maintenance of a healthy pregnancy, and promote a healthy outcome for mother and baby (see Chapter 20).

Health promotion in midwifery

Diet and nutrition

The midwife can provide effective health education in the area of diet and nutrition and may contribute to long-term healthy lifestyle changes (see Chapter 17). The health promotion approach chosen must be client-centred and include health education and empowerment. Behaviour change may also be necessary to promote immediate and long-term health. In an ever-changing healthcare climate where facts and knowledge change as new research emerges, the midwife must maintain current knowledge regarding diet and nutrition as the woman and her family naturally look to the midwife for advice.

New recommendations issued by the Food Standards Agency (FSA) on caffeine, for example, call for a reduction in caffeine consumption during pregnancy from no more than 300 mg to less than 200 mg (FSA 2008). This recommendation is based on two linked studies which showed that babies of pregnant women who consumed between 200 and 299 mg of caffeine per day were at an increased risk of fetal growth restriction which could result in low birthweight and/or miscarriage (CARE Study Group 2008).

Exercise during pregnancy

Most people are well aware of the benefits of exercise and sport, and many women are fitness conscious. Knowledge and understanding regarding exercise during pregnancy will assist the midwife in supporting women who wish to exercise during pregnancy (see Chapter 22).

Exercise has many positive benefits for the individual, including:

It is important to adhere to safety principles during exercise, to enable physiological adjustment to take place, and midwives can use these to advise women (see website for Web Box 19.1). Women should avoid strenuous exercise to exhaustion (may cause blood flow diversion from the uterus, with resultant acute fetal hypoxia) (RCOG 2006a) and ‘jumpy jerky’ movements (NICE 2008).

Just as the maternal system copes with gradual respiratory and cardiac adjustment during pregnancy, the body also adjusts during exercise in a pregnancy identified as low risk. The woman who leads a sedentary lifestyle before pregnancy should be encouraged to undertake gentle exercise during pregnancy (NICE 2010); for example, aquanatal exercise may be a preferred option because of the benefits of non-weight-bearing activity, hydrostatic pressure, buoyancy and upthrust. Additionally, the increased mobility experienced reduces strain on joints and may relieve backache (Dunkley 2000). Walking and swimming may also be useful.

Smoking in pregnancy

Smoking is the largest single preventable cause of mortality and is responsible for reducing the female advantage in life expectancy (ASH 2008). It is a major cause of coronary heart disease, stroke, chronic bronchitis, and lung and other cancers, and is also associated with reduced fertility and early menopause in women (BMA 2004). In pregnancy, smoking is related to spontaneous abortion, placenta praevia, placental abruption, low birthweight and preterm labour (Dewan et al 2003, George et al 2006, Kyrklund-Blomberg et al 2005). Other reports show an association between maternal smoking and wheeze during early childhood (Lux et al 2000).

Women from lower socioeconomic groups are more likely to smoke during pregnancy, which significantly increases the risk of perinatal and infant mortality. Children who are exposed in the home to cigarette smoke are more likely to develop otitis media and asthma and have higher hospitalization rates for severe respiratory illness. Smoking kills (Secretary of State for Health 1998) detailed the Government’s commitment towards helping people quit smoking and reducing the prevalence of those who start. The report identified the provision of funding toward delivering expert help to those most in need and the phasing out of tobacco advertising by 2006. The smoke-free legislation in the UK in 2007 (2004 in Ireland) saw the prohibition of smoking in enclosed public places and workplaces from 1 July 2007 in England.

A report published by ASH (2008) presented a review of progress since 1998 and an agenda for a comprehensive tobacco control strategy. Nationally, smoking in pregnancy fell from 23% in 1995 to 19% in 2000 and then to 17% in 2005, indicating that the Smoking kills target for 2005 was met and the 2010 target is achievable. As there is significant underreporting of smoking during pregnancy, however, the current data are unreliable (ASH 2008).

Smoking cessation: the midwife’s role

The midwife’s role facilitates women’s reception of the support, guidance and advice that is offered, which is generally well received and acted upon (Lumley et al 2004). This unique relationship provides a window of opportunity for health education, which, if delivered appropriately, will not negatively alter the dynamics of the midwife–woman relationship but form an integral part of clinical practice. A client-centred approach and empowerment are more likely to secure and strengthen the midwife’s relationship with the woman and ultimately achieve the health promotion goal than are persuasion, cajoling and scaremongering.

At the first antenatal visit, the midwife establishes the smoking status of the woman, her partner and other members of her household. Specialist smoking cessation counselling should be offered to all pregnant women who smoke (ASH 2008). Midwives may also choose to identify the woman’s readiness to change her smoking behaviour and include her partner, if present, in the discussion. Prochaska et al (1993) developed the behaviour change cycle to assist health professionals in identifying the readiness of clients to change their smoking behaviour (see Box 19.2).

Box 19.2

The model of behaviour change in practice

Contemplator

Is thinking about stopping, may have been thinking about stopping for several years

Ready for action

Ready to stop – may need help and support in doing so

What can I do?

Relapse

Stopped smoking but has restarted

What can I do?

NB: Strategies must be client led and not prescribed by the midwife, whose role is primarily facilitating the discussion and offering support and guidance.

The midwife must increase her understanding of the complex nature of nicotine addiction experienced by smokers and view the process of cessation as more than cutting down or stopping. Women who are highly dependent on tobacco may feel guilty and inadequate at not being able to give it up. The midwife must be encouraging and supportive and ready to offer help to women who express the desire to stop smoking, particularly if they are reluctant to attend smoking cessation counselling. Ten minutes of counselling interaction may be sufficient as an effective intervention for smoking cessation (Lancaster et al 2000).

Reducing the number of cigarettes smoked should generally be discouraged, but praised if this action is taken prior to contact with the midwife. Whilst cutting down, people tend to drag on the cigarette more frequently than usual, inhale more deeply and smoke the cigarette as far to the end as is physically possible (Dunkley 2000). The amount of noxious chemicals inhaled may therefore be the same as the dose inhaled prior to cutting down, when the nature of the smoking behaviour was casual.

Together with current knowledge of specialist support services available in the local area, the midwife can also offer health education leaflets, ‘quit line’ numbers and information about self-help groups, but leaflets should not be used as a replacement for discussion, personal support, sign-posting to other services and advice. Nicotine replacement therapy is considered an option for some women and may be prescribed by their GP after consultation and counselling (NICE 2008).

Damage limitation

Overwhelming evidence shows the association between secondhand smoke and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) – 86% of cot deaths occur in families where the mother smokes (ASH 2008). Further evidence points toward the long-term effects of postnatal neonatal exposure, with associations made between secondhand smoke and heart disease, and increased risk of asthma attacks among those already affected. An association has also been made between secondhand smoke breathed by the pregnant non-smoker and increased maternal circulating absolute nucleated red blood cell counts, which suggests there may be subtle negative effects on fetal oxygenation (Dollberg et al 2000).

The midwife has a responsibility to provide health information and education to women and their families to reduce the damage to the fetus/infant, without making the parents feel guilty. Through two-way communication with the woman and her partner, the midwife should establish the nature of the smoking behaviour and establish their readiness to change. If the woman is ready to stop smoking, the midwife should refer her for specialist support. However, if the woman is not ready to stop, damage limitation advice should be offered. This can involve exploring strategies for reducing the tobacco exposure to the neonate by suggesting that a smoke-free environment is created for the baby; that parents use another room to smoke – outside or near a window. Parents must be actively encouraged to explore strategies that best work for them rather than those prescribed by the midwife. This encourages ownership of plans made and ultimately ensures effectiveness.

Alcohol intake during pregnancy

Alcohol ingestion is a socially accepted behaviour that forms part of everyday social interaction in the western world. Over the past 30 years, the number of women drinkers has increased more than that of men. Excessive alcohol intake is potentially lethal, affecting virtually every organ and system in the body, including the liver, gastrointestinal tract, and cardiovascular and neurological systems. It affects nutrition by suppressing the appetite and by altering the metabolism, mobilization and storage of nutrients (Wardlow 2000). Excessive or chronic alcohol abuse is associated with several vitamin and mineral deficiencies, including folic acid, vitamin B, magnesium and iron. Learning difficulties, loss of memory and other mental problems are associated with infants born to parents who have abused alcohol (Chang et al 1998). Women’s tolerance of alcohol is lower than that of men because of differences in body size, absorption and metabolism. They have a higher proportion of fat to water; therefore alcohol becomes more concentrated in body fluids and damaging effects such as gastritis, pancreatitis, peptic ulcers and malnutrition are more likely to develop.

Drinking alcohol during pregnancy is both teratogenic and fetotoxic (NICE 2008) and excessive intake during pregnancy is associated with fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (see Chapter 48).

Safe measures of alcohol during pregnancy

Despite numerous research studies, to date there is no universally acceptable safe measure of alcohol consumption during pregnancy. In the USA, alcohol consumption of any amount during pregnancy or for women considering a pregnancy is not recommended – advice consistently given since 1981 by the US Surgeon General’s Office. Alcohol-containing products also carry a health warning.

In the UK this advice is not endorsed and a range of options are available that allow some drinking during pregnancy. For example, the Department of Health report Sensible drinking (DH 1995) initially suggested that to minimize the risk to the developing fetus or women trying to get pregnant, no more than one or two units of alcohol per week should be ingested, and this slightly altered on the DH website in 2008 to they ‘should not drink more than 1–2 units of alcohol once or twice a week and should not get drunk’. This view was endorsed by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) antenatal care guidelines stating that women should avoid alcohol during the first trimester and then limit their intake to one to two units once or twice a week for the remainder of their pregnancy (NICE 2008). Whilst there is no evidence of harm from low levels of alcohol intake, there is uncertainty regarding a safe level of alcohol consumption during pregnancy and, as such, complete abstinence of alcohol ingestion during pregnancy should be considered in line with the US Surgeon General’s advice (Mukherjee et al 2005).

Antenatal screening

During the antenatal period, starting at the booking visit, questions relating to alcohol intake should be specific and focused enough to identify women who have a drinking problem. At the first antenatal visit, the midwife should ask the woman if she drinks alcohol. Common responses include, ‘no’, ‘yes’, ‘not really’, or ‘just socially’. Further enquiry must follow to establish clear meaning and specific information to ensure the appropriate health promotion approach is taken. There is a general trend toward underreporting, which will inhibit the identification of high-risk drinkers (RCOG 2006b, Stoler & Holmes 1999). Heavy drinkers may book late for maternity care and require intensive counselling with referral to specialist agencies to help them reduce alcohol consumption. Highlighting teratogenic effects on the fetus forms part of health education, but midwives should be sensitive in ensuring that the information they provide is balanced and informed, and does not result in fear or guilt, as this may impede the woman’s ability to reduce drinking levels.

A useful way of taking a drinking history is to ask specifically about the preceding 7 days. If alcohol has been consumed, the amount in units should be recorded. If intake is higher than RCOG guidelines, the midwife should discuss this with the woman and explore ways of reducing the amount and nature of alcohol intake. While ingesting two units of alcohol over a week may be considered safe (RCOG 2006b), this amount in one evening may not be. A screening tool to detect alcohol abuse recommended by the RCOG is the T-ACE questionnaire (Sokol et al 1989) (see website).

Drugs in pregnancy

Pregnant women should be advised to take only those drugs that are prescribed by a doctor. The British National Formulary (BMA & RPSGB 2008), also available online, offers an excellent guide on drugs contraindicated in pregnancy (see Chapters 10 and 23 and the recommended reading list for further information about drugs in pregnancy and drug misuse).

Domestic violence

Domestic violence (formerly referred to as domestic abuse) poses a serious threat to women’s health and may be emotional, sexual, physical or financial abuse and can result in homicide. It is well established that violence towards women increases during pregnancy (DH 2007, Mezey 1997). The perpetrator is usually the male partner or ex-partner but domestic violence may occur in same-sex relationships, or from other family members.

Abused women and abusers come from all cultural, educational, racial, religious and socioeconomic backgrounds. Midwives must be able to recognize women at risk of violence and provide information and support, acting as a conduit to local resources, support networks and services available (Box 19.3).

Box 19.3

(Lewis 2007:173)

Domestic abuse

New and existing recommendations

Prevalence

Research indicates that domestic violence is widespread in the UK, but it is difficult to obtain reliable statistics as it is generally underreported and therefore a hidden crime. It occurs in all parts of society and is reported to account for 25% of violent crime in the UK (DH 2007). One in three women will experience domestic violence at some time in their lives. It is estimated that 30% of domestic violence starts in pregnancy (Home Office 2004). Reasons for this are numerous and may include feelings of overpossessiveness, jealousy and denial of the women having any other role than spouse. The perpetrator may feel jealous of the woman’s ability to produce a child, or see the fetus as an intruder. He may also become violent because of strained finances or reduced sexual activity (DH 2005).

Risk to the woman and fetus

Domestic violence during pregnancy has been associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, including low birthweight (Kaye et al 2006). The physical and psychological risks to the woman and fetus are overwhelmingly high, and the fetus may be injured or may die during the pregnancy. During 2003–05, the deaths of 19 pregnant or recently delivered women who were murdered were reported to the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the UK (Lewis 2007). The ages of these women ranged from 16 to 45. Five could not speak English and, alarmingly, in all cases the husbands acted as interpreters. It is suggested that many more such deaths are unreported and that this number of 19 should be treated as a minimum. Seventy women reported to the enquiry had features of domestic violence. Most women proactively self-reported domestic abuse to a health professional before or during pregnancy (Lewis 2007). All women were reported to have at least two identifiable risk factors of domestic violence detailed in Box 19.4. None were referred for help or advice. It is important to note that more than 80% of women who died from direct or indirect causes of domestic violence booked late for maternity care (after 24 weeks) or received minimal or no antenatal care (Lewis 2007).

Box 19.4

(DH 2005:48)

Possible signs of domestic abuse in women

None of the above signs automatically indicates domestic abuse. But they should raise suspicion and prompt you to make every attempt to see the woman alone and in private to ask her if she is being abused. Even if she chooses not to disclose at this time, she will know you are aware of the issues, and she might choose to approach you at a later time. If you are going to ask a woman about domestic violence, always follow your Trust’s or Health Authority’s guidance. Or follow the guidance in Section 3.3 of the Responding to Domestic Abuse handbook.

Risks to other family members

In households where there is domestic violence, the children within that household may be affected. They may observe the abuse or be injured directly or indirectly as a result of the abuse (Home Office 2004). The fear experienced and the psychological consequences are immeasurable and may well influence the child’s emotional development. The child may also try to protect younger siblings or take on the role of prime carer. It is reported that 52% of child protection cases involve domestic abuse (Home Office 2004).

The midwife’s role

Due to the number of domestic violence cases that commence in pregnancy, the Department of Health set up the Domestic Abuse and Pregnancy Advisory Group in 2005. This group recommends how health services can meet the needs of pregnant women who are experiencing abuse. It contributed to the development of a handbook for health professionals offering a practical guide on domestic abuse, routine enquiry and training (DH 2005). Routine enquiry for domestic violence during pregnancy has been found to increase the rate of detection, enabling women who disclose domestic violence to seek help early (Bacchus et al 2004).

Routine enquiry about domestic violence should only be carried out if appropriate education and training has been provided, guidelines developed to support staff, and support/referral systems are current and reliable.

When violence is suspected, the best way to confirm suspicion is by direct questioning, which may include the following questions:

The woman may choose to deny being abused, but awareness that help is available is useful. For some women, however, pregnancy provides a unique opportunity for change and disclosure of violence may therefore be likely (Bacchus et al 2004). Routine enquiry of all women antenatally reduces the chances of targeting certain female and male groups that conform to personal stereotypes of those who are likely to be abused and those who may be abusers. Common difficulties for routine enquiry include:

In anticipation of some of these difficulties, several maternity services inform the woman via the booking appointment letter that she will be required to see the midwife alone on at least one occasion during the pregnancy.

Fostering a safe, nurturing and private environment during antenatal visits, with the midwife expressing genuineness, positive regard, empathy and honesty, may provide the woman with an opportunity to seek help should she feel the need. Survivors of domestic violence often feel ashamed about being abused by their partner, have low self-esteem and have conflicting feelings about disclosure, including the repercussions of their actions. Very often, leaving the abuser is not considered a favourable option. Some women are financially and emotionally dependent on their abusers, who often have control over all domestic arrangements. Religious and cultural influences often encourage people to stay in abusive marriages where separation or divorce is considered unacceptable.

The midwife should understand the nature of domestic violence, be sensitive to clues that may suggest abuse (see Box 19.4) and be aware of the impact of abuse on everyday life. When the woman and the midwife are not in the company of the partner – for example, when showing the woman where the toilet is – this may provide an opportunity for the woman to disclose something about how she is feeling that may be indirectly related to the abuse.

Although considered a viable approach, direct questioning is not the only option for obtaining information. Some midwives may be reluctant to acknowledge domestic violence or ask questions about it because of:

Staff should be trained in conflict avoidance to ameliorate the course of violence (DH 2005) and this often increases their confidence.

Each maternity unit and midwifery group practice should have current details about domestic violence units and the Women’s Aid Federation, who provide a safe refuge for those who need it (see details on the website). The Samaritans, Relate and Victim Support all offer support services to survivors of domestic violence. The midwife should be able to supply the woman with relevant local telephone numbers and addresses.

Teenage pregnancy

A teenager is described in different contexts to be a young person under the age of 18, 19 or 20 years of age. The Teenage Pregnancy Strategy considers the key teenage pregnancy group to be those who are under 18 years of age (Department for Children, Schools and Families [DCSF) et al 2008); the Every Child Matters programme (The Treasury 2003) focuses on those between birth and 19 years of age; and the Infant Feeding Survey define their youngest group to be the under-20s for the measurement of national breastfeeding and smoking rates (refer to the website and see Chapters 16 and 23).

Employment and health

For the majority of women, work during pregnancy does not pose a threat to their health or that of their babies (NICE 2008). For some, it may be necessary to modify working practices to promote safety and comfort.

The pregnant woman should avoid heavy lifting. Seating for sedentary workers should be supportive to the back because of increased lumbar lordosis. Standing for long periods should be avoided and rest periods instituted because of the risk of development of varicosities. Smoky environments should be avoided because of the risks associated with passive smoking.

Some occupations may be hazardous to the health of the fetus and expectant mother, including exposure to toxic chemicals (such as lead, pesticides, anaesthetic gases and radiation). Utilization of protective clothing in the home and the workplace, where appropriate, and adhering to safety parameters and work codes will minimize exposure to teratogenic hazards. This makes it important for the midwife to establish the woman’s normal working environment, identify any potential hazards, and provide a conduit for further information should this be required (see website).

Travel

The midwife has a responsibility to raise awareness about travel and health. The most basic but essential information can reduce the risk of harm to the woman, fetus and infant. The UK Government made a commitment to reducing the number of road traffic accidents by one-tenth by 2010 among children and young people in England. Health education during the antenatal period should include issues relating to car seats and the correct application of seatbelts during pregnancy. Pregnant women must be informed about the correct use of seatbelts, including the correct positioning of the seatbelt above and below the uterus (NICE 2008).

Other travel advice given to pregnant women may need to include information about airline travel, particularly ‘long haul’ flights, when the risk of venous thrombosis is increased. Most airlines will not carry pregnant women after 32 weeks’ gestation.

Evaluation

Evaluation is the process by which criteria to determine the value of an idea or method are formulated. The aim of this is to demonstrate the success of the method based on designated aims and learning outcomes.

Without the use of appropriate evaluation tools, the potential to challenge the efficacy of midwifery health promotion is reduced. Evaluation is a worthwhile process and should be used to demonstrate the impact and outcome of interventions deemed to enhance health. Knowledge about the most suitable methods of evaluation is essential not only to highlight the most effective health interventions but also to demonstrate their efficacy to key stakeholders who influence resource allocation. Midwives may use qualitative or quantitative methods of data collection to formulate evaluation results (see Chapters 5 and 7).

Health promotion evaluation can be extremely difficult for the midwife, particularly when assessing long-term success of a health intervention or behaviour change. Other areas that present challenges in terms of evaluation include awareness raising and empowerment.

Reflective activity 19.3

Consider the content of this chapter, and draw up a list of referral agencies for the issues mentioned: Women’s Refuge; alcohol support; local exercise classes; and contacts such as local nutritionist, social worker and health visitors. You can add to this list as you seek out more information for women and families in your area, and you can use this as a reference resource.

Conclusion

Health promotion is an integral part of the midwife’s role, with many potential health-gain benefits for the childbearing population. Understanding the context of health and illness is a key factor in promoting health, and choosing the appropriate health promotion approach to achieve the desired aim is essential if the health promotion approach is to be effective. The midwife’s scope of practice provides room for the public health role to be enhanced and community initiatives to be embraced. The midwife is a vital resource in terms of advice and information on diet, smoking and exercise, and may be a useful means of promoting a healthy lifestyle. The woman may look at her midwife as a role model, and her attitudes and activities may carry as much weight as her words.

The current UK political health agenda recognizes the valuable contribution midwives make to the health of the nation. Rigorous robust evaluation of all health promotion activities will provide evidence of the impact of the midwife’s work in terms of health gain.