Chapter 37 Care in the second stage of labour

Introduction

The anatomical second stage of labour has been traditionally defined as the period from full dilatation of the os uteri to the birth of the baby. However, women do not experience labour and birth by its anatomical divisions, or by the dilatation of the cervix (Gross et al 2006), and labours do not usually progress at a uniform rate.

The distinctive physiological changes that occur just before or around the time the cervical os is fully dilated are traditionally defined as ‘transition’. There is a paucity of formal evidence about the nature of transition, although some observational studies have been undertaken (Crawford 1983, Roberts & Hanson 2007). During or following this phase, the woman begins to feel a variable urge to bear down. Anecdotal evidence indicates that it is not uncommon for midwives to offer women pharmacological pain relief if the urge to bear down occurs when vaginal examination indicates that the anatomical second stage is still some way off. If she then progresses more quickly than expected, such pain relief may inhibit the natural urge to bear down actively. It is thus essential that midwives know how to recognize the transitional phase of labour, and how to support women effectively at this time.

Signs of progress

Transition

Transition occurs at variable times between the late first stage and early second stage of labour. It is recognizable by a change in the behaviour of the woman, and, sometimes, by a change in the nature of the contractions she is experiencing. Any or all of the following may be noted:

If a vaginal examination is undertaken, the mother’s cervical os will typically be found to be between 7 and 9 cm dilated, though smaller dilations have been reported (Downe et al 2008). There have been occasional reports of transition (evidenced by an early pushing urge) occurring when the cervical os is less than 7 cm dilated (Roberts et al 1987).

Reflective activity 37.1

Next time you are with a woman in transition and/or the expulsive phase of labour, ask yourself the following questions. If the answers conflict with local guidelines, or with the usual actions midwives are expected to take locally, consider how these guidelines or informal expectations can be examined by you and your colleagues, with a view to revision.

Expulsive phase

Initially, the strength and consistency of the pushing urge usually varies in intensity, becoming more consistent over time. The woman usually makes a characteristic grunting noise at the height of the contraction. She may feel that her bowels are emptying, which may be very embarrassing for her. The perineum bulges and is stretched thin as it is distended by the descending fetus. The anus initially pouts and then dilates with contractions. The vagina begins to gape, and finally the presenting part is visible.

Some midwives have noted the appearance of a rounded area at the level of the lower back, the so-called rhombus of Michaelis (Sutton & Scott 1996). Sutton & Scott note that it is caused by ‘the pressure of the fetal head [which] … lifts the sacrum and the coccyx out of the way’. They also observe that the woman’s instinctive reaction to the descent of the fetus is to arch her back, push her buttocks out (or off the bed if she is semi-recumbent) and throw her arms back to grasp onto any fixed object behind her. They hypothesize that this is a physiological response, since it causes a lengthening and straightening of the curve of Carus, optimizing the fetal passage through the birth canal.

Others have noted anecdotally that women who have an epidural in situ may experience discomfort under the ribs at around about the time of full cervical dilatation. This may be a function of fetal re-alignment as the fetal head descends, causing a sensation of pressure above the level of the epidural block. The efficacy of these observations in predicting the onset of the second stage of labour for individual women remains to be researched.

If necessary, the midwife can carry out a vaginal examination to confirm full dilatation of the os uteri. If no cervix is felt, there is positive confirmation of the onset of the anatomical second stage of labour.

Physiology of the second stage of labour

Contractions

On average, at this stage, studies have indicated that contractions have an amplitude of 60–80 mmHg, occur every 2–3 minutes and last for 60–70 seconds, although other patterns of second stage contractions can be effective. Marked retraction of the uterus further aids the descent of the fetus through the birth canal. There is no appreciable fall in the height of the fundus, however, because the fetal back tends to uncurl from its flexed attitude and the lower uterine segment stretches. The force of the uterine contractions and secondary powers is transmitted down the fetal spine to its head. This is fetal axis pressure and helps the descent of the fetus through the birth canal.

Secondary powers

The expulsion of the fetus is further aided by the voluntary muscles of the diaphragm and abdominal wall. As the presenting part descends to approximately 1 cm above the level of the ischial spines, pressure from the fetal presentation stimulates nerve receptors in the pelvic floor, and the woman experiences the desire to bear down. This is termed the ‘Ferguson reflex’ (Ferguson 1941). This sensation may occur prior to the end of the anatomical first stage of labour, or at cervical full dilatation. The voluntary muscles of the chest and abdominal wall act reflexively in concert with the uterine contractions to overcome the resistance of the vagina, pelvic floor muscles, and external parts. During this process, the diaphragm is lowered and the abdominal muscles contract.

The pelvic floor

The advancing fetus gradually stretches the vagina and displaces the pelvic floor. Anteriorly, the pelvic floor is pushed up and the bladder is drawn up into the abdomen, where it is less likely to be damaged. Posteriorly, the pelvic floor is pushed down in front of the presenting part. The rectum is compressed; thus any faecal contents will be expelled. The perineal body becomes elongated and paper-thin as it is flattened by the advancing fetus.

Mechanism of labour

As labour progresses, the fetus is moved through the birth canal and induced to make various twists and turns due to the forces which occur, causing it to respond to the contours and planes of the maternal pelvis. These movements are called, collectively, the mechanism of labour. An understanding of this mechanism enables assessment of progress in labour, and recognition of when physiological support may be required, or if a call for assistance should be made.

There is a mechanism for every fetal presentation and position. The widest diameter of the brim of the pelvis is transverse, whereas the widest diameter of the outlet is anteroposterior. To make the best use of available space, the widest presenting diameter of the fetal head usually enters the pelvis in the transverse diameter. As it descends, the fetal head and then the shoulders rotate to emerge in the anteroposterior diameter. The mechanism for the most common presentation is as follows, although it should be noted that the specific physiology of individual women and fetal pairs can alter this mechanism.

The lie is longitudinal, the presentation is cephalic and the presenting part is the area of the vertex. The attitude is one of flexion and therefore the denominator is the occiput. The engaging diameter is the suboccipitobregmatic (on average, approximately 9.5 cm). The position may be either right or left occipitoanterior.

Descent

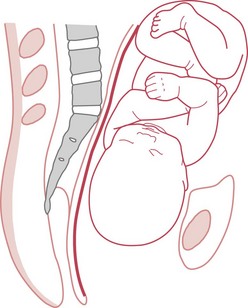

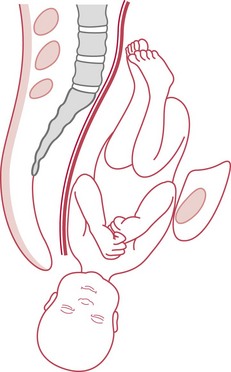

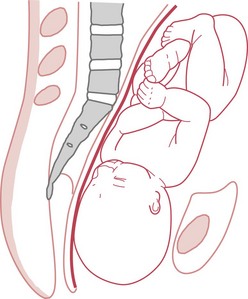

Descent is the process whereby the fetal head moves into the pelvis (Fig. 37.1). Engagement occurs when the widest diameter of the presenting part enters the pelvis. This is more likely to occur prior to the onset of labour in nulliparous women.

Flexion

At the beginning of labour the fetal head is usually in an attitude of natural flexion. As labour progresses, the head meets the resistance of the pelvic floor muscles, and flexion increases. Fetal axis pressure is then transmitted through the occiput, which is pushed down lower as a consequence. The forehead is pushed upwards by the resistance of the soft parts, and so complete flexion is obtained.

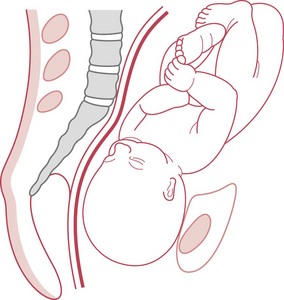

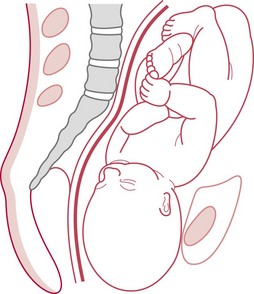

Internal rotation

When the occiput meets the resistance of the pelvic floor, it rotates forward 45° (Fig. 37.2). The slope of the pelvic floor aids this internal rotation forwards, allowing the head to emerge in the longest diameter of the pelvic outlet; that is, the anteroposterior diameter (Figs 37.3 and 37.4). The occiput then escapes under the pubic arch and the head is crowned.

Figure 37.2 Internal rotation occurs. The sagittal suture is in the oblique diameter of the pelvis. (Mother in upright position.)

Crowning of the head

The head is crowned when it has emerged under the pubic arch and no longer recedes between contractions. The widest transverse diameter of the head (the biparietal diameter) is born (Fig. 37.5).

Extension

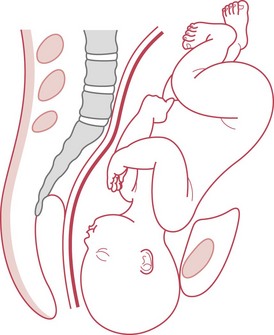

Once the head is crowned, extension takes place to allow the bregma, forehead, face and chin to pass over the perineum.

Restitution

When the head is born, it rights itself with the shoulders (Fig. 37.6). During the movement of internal rotation, the head is slightly twisted because the shoulders do not rotate at that time. The baby’s neck is untwisted by restitution.

Internal rotation of the shoulders

The shoulders undergo an internal rotation similar to that of the head and then lie in the anteroposterior diameter of the outlet. The head, being free outside the birth canal, moves 45° at the same time, so internal rotation of the shoulders is accompanied by external rotation of the head. Rotation follows the direction of restitution; thus the occiput turns to the same side of the maternal pelvis as it was at the beginning of labour (Fig. 37.7).

Lateral flexion

In most supine or semi-recumbent maternal birthing positions, the anterior shoulder is born under the pubic arch first, then the posterior shoulder passes over the perineum. If the woman is in a position in which she is leaning forwards, the posterior shoulder may be born first because of the action of gravity and the effect of the curve of the birth canal (known as the curve of Carus). This curve causes the trunk of the baby to flex sideways as it is born.

Duration of the second stage of labour

The midwife should be aware of the rapidity with which the second stage can progress, especially for multiparous women, since their second stage sometimes lasts only a few minutes. The woman should not be left alone after the late first stage has commenced.

In the presence of effective uterine activity, where there is progressive descent of the presenting part, and the condition of the mother and fetus does not give rise for concern, time alone does not provide sufficient grounds for curtailment of the second stage. Studies in this area demonstrate increased intervention and morbidity over time, but it is not clear if this is due to actual or anticipated pathology (Altman & Lydon-Rochelle 2006). Intervention should be based on the rate of progress and the condition of the mother and baby rather than on the time which has elapsed since full dilatation of the cervix.

Many midwives take note of the pattern of progress in previous labours if the woman is multigravid; or that of labour in the sisters and mother of the labouring woman. This has not yet been tested in formal research studies.

Factors that may slow the progress of the active second stage but which can be corrected by time or by technique include a malpositioned or deflexed fetus (see website for Case scenario 37.1), and use of pain relief (particularly pethidine or epidural analgesia). Corrective techniques for the former include the use of optimal fetal positioning (Sutton & Scott 1996). The effect of pethidine will ameliorate with time. The use of oxytocin routinely in the second stage of labour where an epidural is in situ is not recommended (NICE 2007:122). These NICE guidelines go on to recommend that women with regional analgesia should be enabled to move around and adopt upright positions where possible; that analgesia should be continued through the second stage and until after perineal repair where this is necessary; that pushing be delayed for at least 1 hour to allow for descent and rotation of the fetal head, if all other parameters are normal; and that the second stage should ideally be completed within 4 hours in these circumstances.

Positions in the second stage of labour

If left to their own devices, most women will move around during their labour and birth, as they instinctively adapt to the position of the baby and the progress of the labour. The effect of different positions on the length and outcome of labour has been the subject of much interest and investigation in recent years. Based on the latest Cochrane review in this area at the time they were developed (Gupta et al 2005), current NICE intrapartum guidelines recommend that women avoid the use of supine positions in labour (NICE 2007). The most recent Cochrane review on upright positions in labour reaches a similar conclusion (Lawrence et al 2009).

A woman who does adopt a semi-recumbent position for whatever reason should be well supported by pillows and perhaps a wedge to prevent her from sliding down and eventually adopting the dorsal position. Should this happen, the heavy gravid uterus is likely to compress the vena cava, causing subsequent hypotension, reduced placental perfusion and fetal hypoxia (Humphrey et al 1974, Johnstone et al 1987).

Whatever position the woman chooses, the midwife should be able to adapt the principles of care in labour and management of birth appropriately.

Midwifery care

During this period of maximum exertion, the woman should be praised for her efforts and both she and her partner should be kept fully informed of progress made. Information should be given between contractions, when the woman can relax and attend to what is being said. The midwife can help to promote confidence and allay anxiety by adopting a quiet, calm manner, and through tone of voice, tactile gestures and other non-verbal means of communication. Privacy is essential. It may help to have a ‘do not disturb’ sign on the door. Casual conversation between staff over the woman is never acceptable, and is particularly disrespectful at this time.

Hygiene and comfort measures

The extreme exertion of the woman during the second stage of labour is likely to make her feel hot and sticky. She may appreciate having her face and hands sponged frequently. However, some women find this distracting as it breaks their concentration: it is very much a matter of personal choice. The woman may find drinks of iced water welcome and refreshing. If oral fluids are contraindicated, mouthwashes should be offered.

If leg cramps are experienced, these may be relieved by massage and by extending the leg and dorsiflexing the foot; that is, bending it upwards.

A full bladder may delay progressive descent of the fetus and the bladder may also be damaged by pressure as the fetus advances. Occasionally, if the fetal head has descended deeply into the pelvis and has caused upward displacement of the maternal urinary bladder, the woman may be unable to pass urine and the midwife may also find the passage of a catheter difficult. For this reason it is advisable to encourage regular micturition throughout labour, especially once the midwife recognizes that the expulsive stage of labour is imminent.

Support during transition

This phase of labour can be difficult for the woman and for those attending and supporting her. The midwife needs to be a calm and reassuring presence, and must assess each woman carefully, since individuals react in extremely diverse ways at this time. It is important that the midwife responds to the transitional phase appropriately in each individual case. The aim is to enable the woman to regain her capacity to cope and to trust in her own ability to birth her baby, so that she can take a positive approach to the active second stage of labour. The midwife should also pay attention to the woman’s other birth companions, to ensure that they are reassured that this is a normal part of labour and an indication that the birth of the baby is not far away.

Support during the expulsive phase of labour

Early bearing-down efforts

Traditionally, midwives in the UK have discouraged women from bearing down until the cervical os is known to be completely dilated, particularly in the case of the primigravid woman. This has usually been advised on the assumption that active pushing prior to full cervical dilatation may cause oedema of the os uteri, which will impede or prevent the vaginal birth of the baby (Downe et al 2008). However, a few small-scale observational studies and one US survey (Bergstrom et al 1997, Petersen & Besuner 1997, Roberts et al 1987) have led to suggestions that, where the fetal head is well positioned, and the cervix is more than 8 cm dilated, spontaneous pushing may be physiological (Roberts & Hanson 2007). Given the small size and localized context of these studies to date, best practice in this area remains uncertain.

Techniques for helping women to minimize the bearing-down urge include the use of Entonox; adoption of the left lateral position; controlled breathing techniques; or, at the extremes, the administration of pain relief, including the siting of an epidural. The impact of these techniques on labour progress in this situation has not been subject to formal research.

Delayed bearing-down efforts

Some women may feel little or no desire to bear down when the cervix is fully dilated, probably because the fetal head has not yet descended to compress the tissues of the pelvic floor, and therefore to stimulate muscular contractions, as in the ‘Ferguson reflex’ (Ferguson 1941). The role of the midwife in this situation is to ensure that the woman is well hydrated and not ketotic, and to ensure that maternal and fetal wellbeing are maintained. Assuming all is well, a watch and wait policy can be adopted until the woman begins to experience the bearing-down sensation. For some women, this can be optimized by a change to a more upright position, to encourage descent and the activation of the reflex.

Pushing technique

Organized sustained pushing with contractions, involving breath-holding (closed glottis pushing, known as the Valsalva manoeuvre), is still practised by some midwives in the belief that it reduces the duration of the second stage of labour and therefore the period of highest risk to the fetus. This practice has been challenged intermittently since the late 1950s (Beynon 1957). The most recent authoritative statement on the subject (NICE 2007:164), based on a synthesis of the evidence to date (Bloom et al 2006, Schaffer et al 2005), concludes that women should be informed that in the second stage they should be guided by their own urge to push. If pushing is ineffective or if requested by the woman, strategies to assist birth can be used, such as support, change of position, emptying of the bladder and encouragement.

The observation that the woman tends to push her pelvis forward and arch herself backwards during the second stage of labour throws into question the common practice in many consultant maternity units of encouraging women who use the semi-recumbent position to abduct their legs by bending them and pushing them towards their hips, and to lean forwards as they push. This practice, and the alternatives, require more examination.

There is, as yet, no good evidence on the optimum advice for women who have an epidural in situ during the second stage of labour. However, in the absence of maternal sensation, some degree of direction from the midwife is probably necessary.

Perineal practices

A number of practices are used by midwives in the second stage of labour in an effort to minimize trauma to the perineum. These include the use of hot or cold compresses; perineal massage as the fetal head advances; and guarding with a gentle, or, in some cases, firm pressure, to maintain fetal flexion, and to support the perineal tissues as they stretch. There is very little evidence for the benefits or risks of hot compresses or perineal massage, or for the various oils and techniques used. One large trial of the use of perineal massage found no significant differences on all parameters tested, though for the particular group studied, third degree tears were reduced (Stamp et al 2001).

One large trial assessing the effect of guarding the perineum found a small increase in mild pain at 10 days postpartum in the control group, where guarding was not employed (McCandlish et al 1998). It is not clear whether the techniques used in the study would benefit women using upright positions in labour.

Assessing the need for episiotomy

An episiotomy is a surgical incision of the perineum to enlarge the vulval orifice. The midwife should be aware that pelvic floor and perineal trauma may have long-term implications for the woman and her partner and should not be performed as a routine, even where women have had previous third and fourth degree perineal tears (Carroli et al 2004, Hartmann et al 2005). The possibility of perineal trauma should be discussed with the woman prior to the labour. Her informed choices for this element of labour should be recorded. If an episiotomy becomes necessary, she should be informed, and the midwife must only proceed with her consent. (See Chapter 40 for more details.)

Other midwifery techniques

Optimal fetal positioning

In recent years, the technique of optimal fetal positioning has become increasingly popular (Sutton & Scott 1996). Techniques are proposed for shifting a baby which is malpositioned or asynclitic in labour, including raising one hip, or rotating the hips, to change the angles of inclination of the pelvis. Sutton & Scott also propose that a woman’s instinct to throw her hips forward and her arms back during active pushing should be respected, since this straightens the curve of Carus and optimizes maternal effort. All these observations and techniques have empirical credibility, but remain to be tested formally for their efficacy.

Waterbirth

Therapeutic use of water in childbirth has grown in popularity. Some women may wish to spend most of their labour and birth in the water pool, others choose to spend short periods, and some women may wish to leave the water for the actual birth of the baby and birth of the placenta.

Systematic review evidence indicates that there are a number of benefits to labouring in water (Cluett et al 2004). As there is limited research evidence to guide the midwife in most aspects of waterbirth management, it is necessary to determine the benefits and risks for each woman and baby by a careful individual assessment and attention to official guidance (NICE 2007, RCOG/RCM 2006).

The essential issues to consider are as follows:

Temperature of the water

Too high a temperature will be uncomfortable for the woman and may cause fetal tachycardia (NICE 2007). Cooler temperatures may induce respiration before the baby has been brought to the surface. Temperatures that are comfortable for the woman are recommended (Geissbuehler et al 2002).

Time of entry to water

Immersion in water in the early stages of labour may inhibit uterine activity. Therefore, unless the contractions are particularly strong or painful, some midwives recommend that the woman should refrain from entering the water before the cervical os is 4–5 cm dilated. There is as yet little research to support or refute this practice.

Infection of mother or baby

Infection risk appears to be very low, and can be minimized by using disposable bath linings, where possible, and by thorough cleaning and drying of the bath after use in accordance with current methods of prevention of cross-infection.

Water embolism

In theory, water embolism may occur when maternal placental bed sinuses are torn in the third stage of labour. Water may then enter the circulation. For this reason it is deemed advisable for the third stage of labour to be conducted out of the water. Any oxytocic preparation, if used, should be given when the woman has left the water.

Perineal trauma

The possibility of perineal trauma must be borne in mind. The midwife should provide verbal support to enable the woman to control her birth, allowing the head and shoulders to emerge slowly.

Monitoring maternal and fetal health

The fetal heart can be auscultated using an underwater ultrasonic monitor, wireless electronic fetal monitoring, or Pinard’s stethoscope. If pain relief is required, inhalational analgesia (Entonox) is suitable. The woman must not be left unattended while using inhalational analgesia during a waterbirth. If narcotic analgesia is required, the woman should be asked to leave the water as the drowsiness induced by the drugs compromises safety.

The baby

The baby should be brought to the surface immediately after birth. The umbilical cord should not be clamped and cut while the baby is still under water because the sudden reduction in placental-fetal blood flow may initiate respiration, and thus water inhalation. If the umbilical cord needs to be cut prior to the birth of the baby, the woman should be asked to stand with the baby’s head clear of the water so that the cord may be clamped and cut before the birth of the shoulders.

Preparation for the birth

This is a time of great anticipation and it is now that the true value of the midwife–woman relationship, the strength of the mother, and the skills of the midwife are demonstrated. If the midwife has established a good relationship with the woman and her partner, has enabled the woman to work through her labour with confidence, and has kept the woman and her supporting companions informed of progress and what to expect in the second stage, then the woman and her companions can approach the actual birth with confidence. The atmosphere in the birth room should be calm and unhurried, so that the woman can emerge from the experience with positive memories and intact self-respect. Privacy for the mother must be ensured because it is embarrassing and stressful for her if people repeatedly enter her room.

The midwife should prepare for birth as soon as she suspects that the second stage is imminent. This is especially the case for multigravid women, who can progress very quickly, but some primigravid woman also have very short pushing phases of labour. It is essential to include the women’s vocalizations and behaviour in the judgement of progress, and not to rely simply on the findings of a vaginal examination, or on stereotypes of ‘typical’ patterns of progress.

The room should be clean and warm for the birth of the baby. A warm cot is prepared and resuscitation equipment is checked.

The activities of the midwife during the birth

The actual methods of supporting women during birth can be learned only by experience. However, the principles remain the same and can be applied to whatever position the woman adopts for birth. She must be kept informed at all times, and her wishes must be respected.

A clean area is prepared, including a clean gown or apron and gloves for the midwife. To minimize the risk of contamination from blood or liquor splashes, and of infection with diseases such as HIV, the midwife should also wear unobtrusive eye protection, such as plain spectacles. Any other person likely to come into contact with blood or other body fluids should be similarly protected.

Local anaesthetic and syringe are made available for perineal infiltration prior to an episiotomy, should it be necessary. If the mother has consented to active management of the third stage of labour, a suitable oxytocic drug, such as, Syntometrine® 1 mL or Syntocinon 5–10 units, is checked and drawn up in readiness for use. Discussion should have taken place previously regarding active and expectant management (see Ch. 39).

If the woman is recumbent, the vulva is usually washed with warm solution, the birth area draped with clean or sterile towels, and a clean pad placed over the anus to minimize faecal contamination. Although these activities are common practice, there is no evidence that infection rates are increased if plain water is used, and the practice of draping has not been evaluated in terms of infection rates (Keane & Thornton 1998).

If the woman does not have an epidural in situ, and if the labour has progressed normally to this point, her spontaneous pushing efforts will usually be effective. The midwife will need to provide support and encouragement. If the woman is not in an upright position, and if rapid progress seems to be threatening the integrity of the perineum, the hand can be cupped over the head and the perineum to provide gentle counterpressure, or flexion maintained by placing the palm of the hand lightly on the head with fingers pointing to the sinciput. However, the head must not be held back by excessive pressure, since this risks overstretching and tearing of the deeper structures of the pelvic floor. When women are in more upright positions, a ‘hands off’ approach is usually adopted.

Until the head crowns, it will recede between contractions. It crowns when the widest transverse diameter, the biparietal diameter, distends the vulva, and then no longer recedes. During the birth of the head, the mother is usually asked to breathe steadily in and out to prevent the birth taking place too quickly. Inhalational analgesia can help at this point. Once crowned, the remainder of the head is born by extension. The midwife may change hand position to grasp the parietal eminences to assist in extending the head, if necessary.

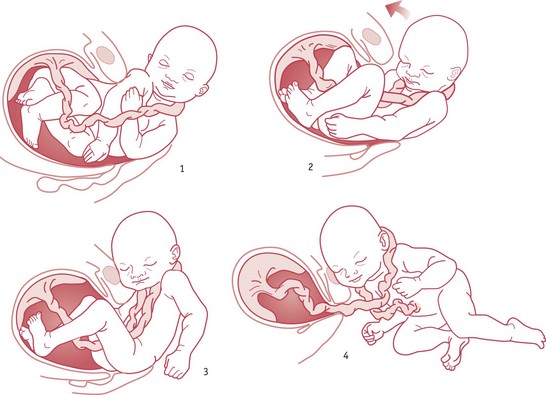

When the child’s head is born, most midwives will check to see if the cord is round the baby’s neck. If so, it is normal practice to free the cord, or to make a loop large enough for the shoulders to pass through. A technique called the ‘somersault manoeuvre’ (Schorn & Blanco 1991) is widely practised in the USA (see Fig. 37.8) and has been adopted by some midwives in the UK. There is, however, no evidence that unlooping the cord as opposed to leaving it in situ improves fetal oxygenation, and some midwives report that they will not check for the cord unless the birth seems to be impeded. Rarely, if it is so tightly round the neck or shoulders as to prevent the birth of the baby, two pairs of artery forceps must be applied 2–5 cm apart, and the cord cut between them and unwound. However, this procedure should only be performed when absolutely necessary, since, once the cord is severed, the baby is no longer oxygenated, and the loss of placental blood flow may further compromise the baby if there is any subsequent delay with the shoulders.

Figure 37.8 Somersault manoeuvre: the head is delivered normally but, as the body is being born, the head is raised towards the symphysis pubis and the body is moved away from the perineum. This allows for minimum tension on the cord; the midwife can more easily unwrap it and allow the infant to reperfuse.

(From Mercer J, Skovgaard R, Peareara-Eaves J, Bowman T. Nuchal cord management and nurse-midwifery practice. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health, September/October 2005. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier.)

If necessary, such as in the presence of meconium or maternal faecal matter, the baby’s nose and mouth can be gently suctioned, and the eyes swabbed, from within outwards, using one swab for each eye. If the woman is in an upright position, any mucus will usually drain spontaneously as the head rests prior to internal rotation of the shoulders. At this stage, some mothers like to be helped into a position to see their baby’s head and watch, or perhaps assist with, the birth of the trunk.

Following restitution and external rotation of the head, the shoulders will normally be in the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvis, although some babies are born with the shoulders in the oblique. If the mother is in the semi-recumbent position, and if the midwife is sure that internal rotation of the shoulders has occurred, the birth can be assisted by placing one hand each side of the baby’s head. With the next contraction, gentle downward traction may be applied to the baby’s head. The anterior shoulder will then come down below the symphysis pubis.

If the mother has consented to active management of the third stage of labour, an oxytocic is given as the anterior shoulder is born. The posterior shoulder is then born by guiding the head in an upward direction and the baby’s trunk is carried towards the mother’s abdomen, being born by lateral flexion. The baby can then be placed on the mother’s abdomen, or in her arms, where she can immediately see and touch it. The time of birth is noted.

If the mother is in an upright forward-leaning position, the posterior shoulder will normally be born first, following the curve of Carus. In this circumstance, the midwife usually only needs to be in a position to receive the baby to ensure that it is brought safely to the ground, or into its mother’s arms.

For most babies, nasopharyngeal suctioning is unnecessary; however, in the presence of meconium or of excessive mucus, it may be required.

Newly emerging evidence suggests that there might be benefits to delaying umbilical cord clamping for a few minutes, or until the cord has stopped pulsating (McDonald & Middleton 2008), particularly for pre-term infants. Whenever the cord is cut, prior to division, the cord is first clamped with two artery forceps, cut between the forceps with blunt-ended scissors, and then sealed close to the umbilicus, usually with a plastic clamp. It is important to ensure that the baby is thoroughly and gently dried and covered warmly to prevent excessive heat loss, while maintaining the skin-to-skin contact with its mother which appears to be an important component of early breastfeeding success (Moore et al 2007). This is an ecstatic moment for the parents and the midwife is privileged to share their joy in the birth of their baby.

Observations and recordings

Transition and the second stage of labour are very demanding for both woman and fetus. It is a time when the capacity of the woman to birth her baby is most tested. It is also a time when the possibility of fetal hypoxia in a previously compromised baby increases as the alteration in uterine activity reduces placental-fetal oxygenation (Katz et al 1987). It is therefore important to continually assess the wellbeing of mother and fetus.

Recordings should include any discussions with the mother, and any decisions she has taken about the way the labour is conducted. The decisions and actions of the midwife must also be recorded. The woman’s general condition and state of mind are noted. Her pulse is taken regularly to rule out rare acute problems, such as intrauterine infection, or a concealed intrapartum haemorrhage. Provided that the blood pressure and temperature have been within normal limits, and there is no history of hypertension or pyrexia, these measures do not need to be recorded more often than hourly. The frequency, strength and duration of uterine contractions are observed, as well as the relaxation of the uterus between contractions. Any sustained loss of uterine activity will result in delayed progress. The midwife will need to reassess the situation to establish the likely cause, and either remedy the situation or seek assistance if necessary.

NICE guidelines recommend that, in the second stage of labour, the fetal heart should be auscultated at the end of a contraction for at least 1 minute every 5 minutes (NICE 2007:161). If continuous electronic fetal heart monitoring is in progress, the cardiotocograph trace should be analysed and assessed for normality.

The amniotic fluid is observed for meconium staining. In a breech presentation, thick fresh meconium is commonly passed at this stage owing to the immense pressure exerted on the breech. While all authorities agree that thick fresh meconium in a cephalic presentation is a serious sign of fetal hypoxia, and that it poses a major risk of meconium aspiration syndrome for the neonate, the significance of thin, old meconium is subject to more controversy. Current NICE guidelines (NICE 2007) recommend continuous electronic fetal monitoring (and transfer for women who are out of hospital) for women with significant meconium-stained liquor, which is defined as either dark green or black amniotic fluid that is thick or tenacious, or any meconium-stained amniotic fluid containing lumps of meconium. NICE recommends that this approach is also considered for women with light meconium staining if a risk assessment that includes stage of labour, volume of liquor, parity, and the fetal heart rate suggests that this might be advisable (NICE 2007).

All observations, including the timing of the various stages and phases of the labour, must be recorded in locally approved labour records. Independent midwives are advised to agree their records in collaboration with their local supervisor of midwives. All actions taken by the midwife must be noted. Each entry must be dated, timed, and signed legibly. Entries made by students must always be countersigned by the attending midwife.

Future research in this area

Over the last few years there has been an increase in interest in the nature of normal birth and its consequences. Some of the gaps in the evidence in this area have been identified above. Examples of the areas of research relevant to midwifery that are likely to grow over the next few years include:

Conclusion

For many years it has been assumed that the second stage of labour can be strictly delimited and predicted. Increasing attention to women’s actual experiences has led to more formal recognition of the fluidity of the phases of labour, and to an acknowledgement of the nature of transition. Whatever the eventual findings of future research in this area, transition and the expulsive stage of labour remain times of intense hard work, profound psychological impression, and great exhilaration for the mother, her partner, and possibly her baby. The empathetic and skilled midwife is an essential companion on the journey to motherhood that is represented by this stage of labour.