Chapter 55 Medical disorders of pregnancy

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

Introduction

Midwives are mainly concerned with normal pregnancy; however, they must be aware of pre-existing conditions which make a woman unsuitable for booking in a low-risk environment and be able to recognize signs of deterioration in a woman’s condition, and know what action to take (Lewis 2007, NMC 2008). With modern treatment, many women with medical conditions who previously would not have reached childbearing age, now do so. Trends in childbearing also show that women are having children at a later age, by which time they may have developed medical conditions such as heart disease, hypertension and diabetes which are associated with unhealthy lifestyles and obesity (Lewis 2008). Lewis also suggests that while health professionals have given effective attention to the ‘big obstetric killers’ such as haemorrhage, sepsis and pre-eclampsia, more women now die from indirect causes relating to their medical conditions (Lewis 2008).

Women with pre-existing medical conditions have often received lifelong treatment and are experts in their own care and treatment. They will often be familiar with a medical team, and may have received pre-conception advice prior to planning the pregnancy. More rarely, they may have received advice against becoming pregnant and may be considering a termination, or have deliberately decided to embark on a pregnancy regardless of personal risk. Whether or not the pregnancy continues, women with complicated pregnancies report that they feel ‘out of control’ and experience high levels of anxiety. They feel the focus of pregnancy is on the fetus and once the baby is born, care is not so intense, so they feel isolated in the postnatal period (Spencer 2007, Thomas 1999).

An in-depth approach to all medical conditions is beyond the scope of this chapter; however, a range of medical conditions is considered, all of which, if disclosed at the antenatal booking interview, require a multidisciplinary approach (NICE 2008a). It cannot be overemphasized that some of the signs and symptoms associated with severe maternal illness, such as breathlessness and heartburn, are common towards term in a normal pregnancy, which is why they can be easily overlooked or disregarded (Lewis 2007).

Some conditions are discussed in further detail in the chapter, outlining the effects on mother and fetus/neonate, treatment, and specific midwifery care. Recommendations are given on the website for further reading, and include some of the excellent new publications, specifically written for midwives.

Anaemia

Anaemia is a deficiency in the quality or quantity of red blood cells, resulting in reduced oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood. In the UK, NICE guidelines for antenatal care indicate that routine iron supplementation during pregnancy is unnecessary, suggesting that investigations and/or supplementation are warranted only when haemoglobin levels are lower than 11 g/dL at first contact, and 10.5 g/dL at 28 weeks (NICE 2008a). However, Evans (2008) suggests that iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) has a profound impact on women’s lives throughout the lifespan, and that postnatal anaemia contributes to poor health and low mood which is frequently overlooked. Work from the World Health Organization (WHO) also highlights the risks of anaemia to pregnant and non-pregnant women (WHO 1992), and this was illustrated by data gathered by McLean et al (2007) which plotted the prevalence of anaemia in children and women of reproductive age throughout the world, indicating the highest rates in the African and Indian continents.

Iron deficiency anaemia

Iron deficiency is the commonest cause of anaemia in women. Anaemia may predate pregnancy, arising from poor diet, menorrhagia, or repeated pregnancies, especially if close together. Bleeding from haemorrhoids or antepartum haemorrhage may also cause anaemia, as may hookworm or parasitic infestation.

Investigations

After taking a detailed history about general health, diet, infection, blood loss and other relevant information, further investigations such as haemoglobin level, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), packed cell volume (PCV), total iron binding capacity, and serum ferritin will give a full picture (McKay 2000, NICE 2008a) (see Ch. 33).

Management

Where iron deficiency anaemia has been diagnosed, oral iron 120–140 mg daily may be given as:

Women need to know that iron absorption is enhanced by vitamin C and inhibited by tannin in tea, and that there might be some side-effects, such as blackness of stools, nausea, epigastric pain, diarrhoea and constipation. Side-effects may be reduced by taking the iron after meals, although this decreases iron absorption. It may be better tolerated at bedtime, and by leaving 6 to 8 hours between doses. However, the type and dose may need to be changed if symptoms persist (Jordan 2002). This is also a good opportunity for the midwife to provide dietary advice (see Ch. 17).

In more severe cases of anaemia, the woman may be given intramuscular injections of iron. Special precautions should be taken when administering this, to avoid permanent staining of the skin (Jordan 2002).

Folic acid deficiency anaemia

Folic acid is necessary for formation of nuclei in all body cells. In pregnancy, when there is proliferation of cells, a deficiency may occur unless the intake is increased.

Management

Dietary sources of folic acid are lightly cooked green leafy vegetables, such as broccoli and spinach (see Ch. 17). Following the demonstrated link between neural tube defects and intake of folic acid, all pregnant women, and those intending to become pregnant, are advised to take 0.4–4 mg folic acid daily (NICE 2006).

Haemoglobinopathies

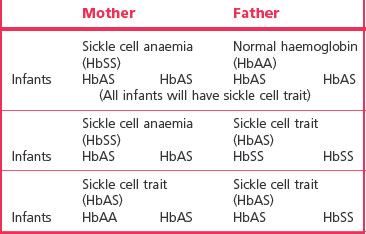

Haemoglobinopathies are inherited conditions in which one or more abnormal types wholly or partly replace normal adult haemoglobin, HbA. The main haemoglobinopathies which complicate pregnancy are sickle cell disease and thalassaemia. These conditions are genetically complex and are presented here in a simplified form, with patterns of inheritance illustrated in Tables 55.1. and 55.2.

Table 55.1 Haemoglobin combination in sickle cell disorders

| HbSS | Homozygous sickle cell disease (sickle cell anaemia) |

| HbSC | Heterozygous sickle cell disease (sickle cell C disease) |

| HbCC | Homozygous CC disease (not a sickling disorder) |

| HbS beta/thal | Sickle/beta thalassaemia |

| HbAS | Sickle cell trait |

Sickle cell trait and sickle cell disease

In sickle cell disease, erythrocytes containing HbS have a short lifespan of 5–10 days (rather than the normal span of 120 days). ‘Sickling’ occurs when cells become sickle shaped under conditions of low oxygen tension, including hypoxia, dehydration, infection, acidosis and cold (Dike 2007, Nelson-Piercy 2006). Cells are easily haemolysed and cause extremely painful vaso-occlusive symptoms in joints, in the abdomen and in the extremities during acute exacerbations, known as a crisis. This leads to chronic haemolytic anaemia, and an increase in the rate of haemoglobin synthesis in the bone marrow, which may lead to folic acid deficiency. Other complications are thromboembolic disorders, retinopathy, renal papillary necrosis, leg ulcers, and increased risk of infection because of disorders in the function of the spleen (Dike 2007, Nelson-Piercy 2006). Acute chest syndrome may occur, in which there is pyrexia, tachypnoea, leucocytosis and pleuritic chest pain.

Effect on pregnancy

The diagnosis is usually made in childhood, once most fetal haemoglobin (HbF) has been replaced, and all women at risk should be tested. Nelson-Piercy (2006) observes that 35% of pregnancies will be complicated by crises, and perinatal mortality is increased four- to sixfold. Pregnancy may be complicated by increased risk of miscarriage, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), preterm labour, and pre-eclampsia.

Management

Pregnancy

All women at risk, together with their partners, should be screened for haemoglobinopathies in early pregnancy. Iron therapy should be avoided but folic acid given routinely throughout pregnancy. Blood transfusions may be required to treat severe anaemia, and exchange transfusions carried out to remove abnormal HbS and replace it with normal HbA, although the advantages of this are debatable.

Women with sickle cell disease may have poor appetites and need to have regular small meals including meat, fish, eggs, cheese, fruit and wholemeal bread. They should be aware of the symptoms of infection, and who to contact if they feel unwell. In the case of a crisis, the woman will be admitted to hospital, where she should be kept warm, and given pain relief, usually morphine (Nelson-Piercy 2006). Oxygen levels are monitored by pulse oximetry or arterial blood gases.

Labour

Dehydration, acidosis and infection all lead to sickling, and must be avoided, whilst avoiding fluid overload. Unless there are obstetric indications, caesarean section is not indicated, and general anaesthesia should be avoided. Management must involve the haematology department, and colleagues knowledgeable in the care and management of women with sickle cell disease, and the woman should be encouraged to report any problems.

Thalassaemia

Thalassaemia is a condition in which there is an abnormal amount of HbA2. It is most common in people of Mediterranean and Asian origin. The condition arises from defects in the alpha or beta globin chains resulting in thin, shortly lived red cells, often misshapen and deficient in haemoglobin, causing profound anaemia. As with sickle cell trait, thalassaemia in its mild forms confers some protection against malaria.

Other causes of anaemia

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G-6-PD) deficiency

This rare, X-linked inherited enzyme deficiency typically affects people of African, Asian and Mediterranean origin. Haemolytic crises occur if the affected person takes certain drugs, including antimalarial preparations, sulphonamides and antibiotics (nitrofurantoin, nalidixic acid and possibly chloramphenicol) or eats broad (fava) beans. It may be implicated in cases of prolonged neonatal jaundice.

Heart disease

Heart disease is the leading non-obstetric cause of maternal death in the UK, with 48 maternal deaths reported in the triennium 2003–2005 (Lewis 2007). Myocardial infarction is the most common cardiac cause of maternal death. The total incidence of cardiac disease in pregnancy is 0.5–2% (McLean et al 2008).

Signs and symptoms of cardiac disease are:

During pregnancy, women with pre-existing heart disease may experience a worsening of symptoms, due to physiological changes of pregnancy (see Ch. 31). There is an increase in circulating blood volume, increased resting oxygen consumption, decreased peripheral vascular resistance, an increase in stroke volume and a slight increase in resting heart rate (Adamson et al 2007). These changes influence haemodynamics, increasing strain on the heart, which is further compromised during labour. A wide range of conditions affect the heart in a mild, moderate or severe way, and conditions may be congenital or acquired, as outlined below.

Congenital heart disease

Congenital defects relate to the structure of the heart, and the most common are atrial septal defects, patent ductus arteriosus, and ventricular septal defects. Other more serious lesions include Fallot’s tetralogy (ventricular septal defect, pulmonary stenosis, overriding aorta and right ventricular hypertrophy) and Eisenmenger’s syndrome (ventricular septal defect, overriding aorta and right ventricular hypertrophy). Most lesions are corrected by surgery in childhood. Marfan’s syndrome is a genetic condition in which cardiac anomalies occur. Pregnancy outcome is worst where there is pulmonary hypertension in Eisenmenger’s syndrome and in Marfan’s syndrome where there is aortic involvement (Adamson et al 2007). Many pre-existing cardiac disorders are complex, and pre-pregnancy counselling is essential, so that women know their own health status in relation to likely outcome. Some women, particularly those with cyanotic heart disease and pulmonary hypertension, may be advised to avoid pregnancy, or, if pregnant, may be advised to have termination of pregnancy (Adamson et al 2007). However, the woman’s choice must be respected.

Acquired heart disease

This usually involves damage to heart valves, such as stenosis, where the valve is constricted, or incompetence, where the valve fails to close completely. Valvular problems are often subsequent to infection or rheumatic heart disease, now rare in the UK but prevalent in developing countries, and a problem for immigrant mothers (Lewis 2007). Women who have had valve replacements will be on anticoagulant therapy, and choices need to be made to balance the need for anticoagulants against the risks they pose for the fetus. Warfarin is teratogenic in early pregnancy and may lead to fetal haemorrhage at any time. There is considerable debate about appropriate combinations of warfarin and heparin and whether fetal risks may be reduced by changing to self-administered subcutaneous or intravenous heparin, which does not cross the placenta, after the first trimester (Adamson et al 2007). The effects of heparin are reversed by protamine sulphate.

Peripartum cardiomyopathy is a rare, functional, cardiac complication, with sudden cardiac failure, arising in the last month of pregnancy or in the first 5 months postpartum, where there has been no evidence of heart disease pre-pregnancy. It is more common in women of black race, multiparity, and higher maternal age, and is a significant cause of maternal mortality (Adamson et al 2007, Lewis 2007, McLean et al 2008).

Antenatal care

Pre-pregnancy counselling and then care in a dedicated antenatal cardiac clinic are required, with input from obstetrician, cardiologist, anaesthetist and midwife (Adamson et al 2007).

Aims of antenatal care are to detect heart failure and disturbances of cardiac rhythm. Women and their partners need help and support during what may be a particularly anxious time. Practical help may be needed with housework, transport to clinics and childcare.

A high-protein, low-carbohydrate, low-salt diet is recommended. Weight control is important, as excessive weight gain places extra strain on the heart. Infection is treated with antibiotics to reduce the risk of bacterial endocarditis; dental work, which may be a potential source of infection, should be carried out early in pregnancy.

Major antenatal complications are acute pulmonary oedema and congestive cardiac failure. Women and partners should be aware of symptoms which indicate worsening of the condition, such as dyspnoea, cough or chest pain, which will need hospital admission immediately for stabilization.

Labour

Depending on the type of cardiac disorder and the progress of the pregnancy, labour may be spontaneous or induced or an elective caesarean section may be carried out. Prophylactic antibiotics may be given to reduce the risk of bacterial endocarditis (Adamson et al 2007). Epidural analgesia is recommended, but with caution in regard to hypotension, and it is contraindicated in women on anticoagulant therapy. The optimum position for the woman is the ‘cardiac position’ supported left lateral, or semi-upright, with the legs lower than the abdomen (Adamson et al 2007). In addition to usual midwifery observations in labour, the following are important:

In the absence of obstetric complications, vaginal delivery causes less haemodynamic fluctuation than caesarean section (Adamson et al 2007).

There is no reason for elective instrumental delivery if birth is proceeding well; however, excessive pushing should be avoided since it alters haemodynamics and may compromise cardiac activity. If the woman feels the urge to push, short pushes with the mouth open should be encouraged. Sudden strong uterine contraction in the third stage may direct so much of the uterine circulation of blood to the systemic circulation that the impaired heart may become seriously compromised, therefore ergometrine and syntometrine are not used. Syntocinon should be used with caution, and is contraindicated in cases of heart failure (Adamson et al 2007).

Postnatal care

Continuing close observation of vital signs is necessary as heart failure or peripartum cardiomyopathy may occur in the first few days postnatally. Women require rest, but not complete immobilization. Physiotherapy helps to reduce the risk of thromboembolic disorders. There is usually no contraindication to breastfeeding. The risk of congenital heart disease in the baby is increased and, therefore, careful examination of the baby is essential.

Careful plans should be made for transfer to the community. Women need practical help to enable them to rest, and cope with the demands of the baby. An appointment should be made with the cardiologist 4–6 weeks postnatally, to assess cardiac function. Advice should be given on appropriate contraception postnatally, and pre-conception counselling for future pregnancies.

Thyroid disorders

Physiological changes in pregnancy lead to alterations in thyroid function and iodine uptake, and can adversely affect women who have pre-existing thyroid disorders, as described below.

Thyrotoxicosis (hyperthyroidism, Graves’ disease)

Thyrotoxicosis occurs in about 1 : 500 pregnancies, with 95% of these associated with an autoimmune disorder in which thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor antibodies are produced. When untreated, the condition is associated with infertility, but conception occurs commonly in women who are treated. The condition does not appear to be made worse by pregnancy (Nelson-Piercy 2006).

Women with thyrotoxicosis experience sensitivity to heat, tachycardia, palpitations, vomiting, palmar erythema and emotional lability. Whilst all of these are also features of normal pregnancy, women with thyrotoxicosis also experience weight loss, tremor, persistent tachycardia, eyelid lag and prominent eyes. The disease usually predates pregnancy, but may arise for the first time in the first or early second trimester (Nelson-Piercy 2006) and may be mistaken for hyperemesis gravidarum.

If untreated, there is an increased risk of miscarriage, IUGR, preterm labour, and perinatal mortality. In women who are poorly controlled, there is a risk of a thyroid crisis, or ‘storm’, with hyperpyrexia, palpitations and tachycardia, which may lead to heart failure, especially in labour (Nelson-Piercy 2006).

Treatment

Treatment is by carbimazole or propylthiouracil (PTU), either for 12–18 months following diagnosis, or over a longer period. Both drugs cross the placenta (PTU less so) and may cause fetal hypothyroidism and/or goitre (Nelson-Piercy 2006), but they are unlikely to cause teratogenic problems at therapeutic levels. In the early management of the disease, beta-blockers may be given for the first month to control palpitations, tachycardia and tremor.

Fetal effects are unlikely with good control, but outcomes are unpredictable. There may be fetal tachycardia, IUGR, fetal goitre, and a 50% increase in mortality if the disease is untreated. After delivery, the baby may develop thyrotoxicosis, with weight loss, tachycardia, jitteriness, and poor feeding. Treatment is by antithyroid drugs. The neonatal condition will resolve once maternal thyroid-stimulating antibodies have cleared from the neonatal system.

During the antenatal period, assessment of maternal heart rate, weight gain, and experience of nausea and vomiting should be carried out. Clinical assessment of fetal condition includes monitoring for IUGR; listening to the fetal heart; and may include serial ultrasound scans to assess growth and to detect goitre. During labour, observation of temperature, heart rate and rhythm are necessary, in addition to usual midwifery care. Minimal amounts of antithyroid drugs are excreted in breast milk, so breastfeeding is not contraindicated (Nelson-Piercy 2006).

Hypothyroidism

This occurs in about 1% of pregnancies and there is usually a family history. It is characterized by weight gain, lethargy, hair loss, dry skin, constipation, fluid retention, carpal tunnel syndrome and possibly goitre. There is also intolerance of cold and a low pulse rate. Like hyperthyroidism, it is thought to be an autoimmune disorder.

Untreated, it may lead to infertility, increased risk of miscarriage and fetal loss. Treatment is by thyroxine supplementation, and when well controlled there are no adverse effects on pregnancy. Little thyroxine crosses the placenta, and neonatal hypothyroidism is very rare (Nelson-Piercy 2006).

Renal conditions

Three common forms of urinary tract infection occur during pregnancy: asymptomatic bacteriuria, cystitis and pyelonephritis. Infection may arise in pregnancy because of physiological changes, as the ureters and pelvis of the kidney become dilated and urinary stasis may occur. Dilatation of the ureters is further accentuated when the enlarging uterus presses on the ureters at the pelvic brim, particularly on the right side since the uterus inclines to the right. Other predisposing factors are vesicoureteric reflux of urine containing bacteria, urinary catheterization (even with impeccable technique), and abnormalities of the renal tract (Gilbert & Harmon 2002).

Causative organisms

The main causative organism is Escherichia coli, a normal inhabitant of the intestines, which may increase in virulence during pregnancy under the influence of oestrogen. Occasionally, other organisms, such as Proteus vulgaris, Streptococcus faecalis or Pseudomonas aeruginosa, are involved.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

Between 2% and 10% of all women have asymptomatic bacteriuria, that is, the presence of more than 100,000 colony-forming units of a single organism per millilitre of urine (Nelson-Piercy 2006). Untreated, it leads to urinary tract infection in 30–40% of women, in the form of cystitis and/or pyelonephritis. NICE guidelines recommend that women are offered screening for asymptomatic bacteruria (NICE 2008a).

Cystitis

Cystitis, or infection of the urinary bladder, occurs in up to 1.5% of pregnancies. Women may experience:

Diagnosis is by culture from a midstream specimen of urine, and treatment is by antibiotics, typically ampicillin. Follow-up testing of urine should be carried out as the condition may recur. Women should be advised to drink plenty of fluids, preferably not acidic or carbonated, to wipe the perineum from front to back, and to empty the bladder immediately before and following sexual intercourse. Cranberry juice or capsules may help in the treatment and prevention of urinary tract infection, particularly that associated with E. coli (Lavender 2000). It is thought that tannins in cranberries prevent P-fimbriated E. coli from attaching themselves to uroepithelial cells, thereby inhibiting infection. Low-sugar versions are suitable for women with diabetes.

Women also need to know the signs and symptoms of further infection and be encouraged to report these to the midwife or GP (Gilbert & Harmon 2002), as ascending infection may lead to the more serious condition of pyelonephritis.

Pyelonephritis

Pyelonephritis occurs in 1–2% of all pregnancies and is more common in women who exhibit bacteriuria (Nelson-Piercy 2006). Renal tubules become inflamed, and their ability to reabsorb sodium is adversely affected. Normally, sodium and water are excreted in the urine, but where reabsorption is affected, they remain in the body, causing oedema and increased pressure on the cardiovascular system. There is a consequent decrease in urine output. Additionally, buffer production of potassium and ammonia is affected, causing accumulation of free hydrogen ions and acidaemia.

When glomerular damage occurs, nitrogenous waste cannot be removed from the blood, causing an increase in serum creatinine, urea and uric acid, and a decrease in urinary creatinine, urea and uric acid. Glomerular damage also causes loss of plasma proteins into the urine, changing osmotic pressure and leading to further oedema (Marieb 2006).

Thus, infections need to be treated quickly and effectively, and the woman’s wellbeing and response to treatment carefully monitored.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is confirmed by microscopic examination of a midstream specimen of urine. This will reveal pus cells and more than 100,000 bacteria per millilitre. The urine is acid, smells offensive and contains red blood cells and protein. Blood cultures may also be taken.

Management

The woman may be admitted to hospital for rest, observation and treatment. A broad-spectrum antibiotic such as ampicillin (500 mg every 6–8 hours) is usually prescribed but may be changed once sensitivity of the causative organism is established. Initially, intravenous administration is more effective. The woman should drink plenty of fluids to avoid urinary stasis. Fluid balance is monitored.

Lying on the unaffected side will help to relieve the pain and assist drainage. Analgesics are prescribed as necessary. Temperature, pulse and respirations are recorded 4-hourly. Midstream specimens of urine are tested until urine is free of pus. The haemoglobin is checked due to risk of anaemia.

Recurrence of the infection may occur during pregnancy or postnatally, necessitating follow-up. Antibiotic therapy is continued for a month, and sometimes throughout pregnancy. Three months following delivery when the renal tract has returned to normal, further renal investigations may be carried out (Gilbert & Harmon 2002).

Effects on the fetus

Risk of miscarriage and preterm labour is increased, and maternal hyperpyrexia may result in intrauterine fetal death. Preterm labour may not be recognized if the woman is already in severe pain from the illness, and labour may only be detected by cardiotocography. Maternal plasma volume may be reduced, leading to poor placental perfusion. This can result in IUGR. There may also be fetal hypoxia. If the mother has a urinary tract infection at the time of delivery, the infant is at substantial risk of congenital infection.

Chronic renal disease

Chronic renal disease may arise as a result of any of the following:

The underlying pathophysiology described for pyelonephritis leads to the same maternal and fetal consequences in chronic renal disease. However, chronic renal disease is further complicated when damage to renal tissue results in reduced blood supply to the kidney. When this occurs, renin is produced to increase blood supply (see Ch. 56), with a consequent rise in blood pressure.

Chronic renal disease is usually classified as mild, moderate or severe, depending on levels of plasma creatinine (Nelson-Piercy 2006). Women with severe disease may be advised against pregnancy, since 85% of them are likely to experience problems.

The outcome of pregnancy depends on the nature and severity of the disease. Outcome is best where renal function is only moderately compromised, with little or no hypertension, and worse where renal function is less than 50% (Nelson-Piercy 2006). The woman is at risk of deterioration of renal function, proteinuria, and worsening of hypertension. There is also an increased risk of miscarriage, superimposed pre-eclampsia, IUGR, preterm delivery and fetal death.

The aim of care is to avoid further deterioration in renal function. More frequent antenatal visits are required for maternal and fetal monitoring by the multidisciplinary team. The woman may need extra rest and help with childcare and household work. She may need to be admitted to hospital for rest and observation. Labour and delivery may be spontaneous or induced, or elective caesarean section may be performed, depending on maternal and fetal condition.

Renal transplant

Following successful renal transplantation, pregnancy occurs in 1 in 20 female transplant patients of childbearing age (Robson 1999).

Pre-pregnancy counselling is essential for these women, and, generally, the following advice is given:

The woman should be cared for by a nephrologist and an obstetrician; however, she still requires midwifery care and support. Regular monitoring of blood pressure, renal function and fetal condition, including ultrasound assessment of growth and Doppler studies of umbilical and placental circulation, must be carried out.

Predisposition to urinary tract infection in pregnancy and immunosuppressive drugs taken by transplant patients make the woman prone to infection. Hypertension and anaemia can also occur.

Labour may occur spontaneously unless there is an obstetric indication for intervention. Steroid therapy is increased and antibiotics must be given prophylactically for any surgical intervention, including episiotomy (Nelson-Piercy 2006).

Neonatal problems include preterm delivery, IUGR, respiratory distress syndrome, adrenocortical insufficiency, thrombocytopenia, leucopenia, cytomegalovirus and other infections. Theoretically, breastfeeding is possible, but so many uncertainties surround the effects of some of the drugs used that it is not advised (Joint Formulary Committee 2008).

Acute renal failure

A fall in urinary output is the first sign of acute renal failure. An output of less than 500 mL in 24 hours is considered a sign of renal failure.

Causes

Acute renal failure in pregnancy is rare (0.005%), but mild to moderate renal impairment may occur (Billington & Heptinstall 2007). It may occur in association with severe haemorrhage, pre-eclampsia and eclampsia and infection, including septic abortion. It is rarely associated with pyelonephritis (Nelson-Piercy 2006). The kidneys are unable to excrete creatinine and urea, with rising serum levels leading to acidosis. Though rare, it is serious and its course is unpredictable. Women with renal failure should be transferred to a unit where renal dialysis is available.

Management

Management depends on the cause, which may be pre-renal (e.g. hypovolaemia) or renal (tubular or cortical necrosis). It is important to be aware that acute renal failure can occur and to prevent its onset by adequate fluid replacement, while avoiding fluid overload, which particularly in cases of pre-eclampsia, can lead to pulmonary oedema (Nelson-Piercy, 2006). Emphasis is on avoiding and/or treating uraemia, acidosis, hyperkalaemia and fluid overload. Renal dialysis may be needed.

Women and their families need support from the multidisciplinary team, since not only is the woman extremely ill but also she will be concerned for her baby. Postnatal care should include full information about the nature of her illness, effects on future pregnancies and information about appropriate contraception.

Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes is a disorder of the endocrine system that affects the metabolism of carbohydrates, fats and protein. Glucose is essential to cell function, and, in a complex metabolic process, insulin enables glucose to enter cells. It is important to remember that in diabetes there is no shortage of glucose, rather there is a lack of insulin. Diabetes affects many body systems, although the principal signs and symptoms of diabetes arise as the body tries to metabolize fat and protein to provide energy.

The main signs and symptoms are hyperglycaemia, thirst, polydipsia, fatigue and blurred vision. Some 2–4% of pregnancies involve women who have diabetes, and there are associated risks for the woman and her baby, with generally poorer outcomes than for women who do not have diabetes (NICE 2008b). Understanding of the condition and how it affects and is affected by pregnancy is, therefore, essential for midwives. Diabetes arises for a number of reasons and is classified as follows.

Type 1: insulin-dependent diabetes (IDD) mellitus

This is most common in young people and there is an almost complete lack of insulin, because of an absence of, or destruction of, beta cells in the pancreatic islets of Langerhans. This type of diabetes is insulin dependent. It is a genetically mediated autoimmune disorder involving human leucocyte antigens (HLA) on chromosome 6 (de Swiet 2001). Hyperglycaemia, polyuria and ketosis are present and there is usually significant weight loss. Untreated, or poorly controlled, this can lead to metabolic acidosis, coma and death. Type 1 diabetes causes multisystem, microvascular complications, relating to high levels of blood glucose. Complications include retinopathy, causing problems with vision; nephropathy, causing deterioration in renal function and associated hypertension; and neuropathy, mostly affecting the feet and legs which may lead to ulceration and gangrene. Those with type 1 diabetes are also more likely to develop cataracts.

Type 2: non-insulin-dependent diabetes (NIDD) mellitus

This condition can exist without any symptoms. There is resistance in the tissues to the action of insulin; it is often diagnosed later in life, and frequently affects those who are overweight. It is not dependent on insulin, and may be controlled by weight loss and diet, or by oral hypoglycaemic agents.

Gestational diabetes mellitus

The glucose tolerance test is normal except in times of stress, when there may be signs of diabetes. When this occurs in pregnancy, it is known as gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). NICE guidelines do not support routine screening for GDM (NICE 2008b), but deem it appropriate if the woman has any of the following risk markers at the first antenatal booking interview:

In these cases, screening should be offered. Where the woman has previously had GDM, she can monitor blood glucose herself in early pregnancy, or a 2-hour 75 g oral glucose tolerance test can be offered at 16–18 weeks. If abnormal, treatment would be started; if normal, it can be repeated at 28 weeks (NICE 2008b).

Midwives need to be aware that women with gestational diabetes and those with pre-existing diabetes mellitus require knowledgeable and skilled care with a recognition of them as women in their own right rather than a reflection of a medical condition.

Pregnancy and diabetes

A number of hormonal and metabolic changes occur naturally as a result of pregnancy, and these changes, together with their accepted physiological norms, have been well documented (see Ch. 17).

Type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus are complicated by the physiological changes which take place in glucose metabolism during pregnancy and, as previously stated, diabetes may develop during the pregnancy.

Care of women with diabetes

Pre-conception care

Although more complications occur in the pregnancies of diabetic mothers, the maternal mortality rate is no higher than 0.5% (Nelson-Piercy 2006). Good glycaemic control pre-pregnancy can help reduce the risks of miscarriage, congenital malformation, stillbirth and neonatal death, as can folic acid supplements (5 mg/day, taken pre-conception and up to 12 weeks’ gestation). Weight control is important and women with a BMI over 27 kg/m2 should be encouraged to lose weight. Retinal and renal assessment should be offered. Women should be advised about local and national support systems (NICE 2008b). Maternal and fetal risks and complications affecting women with pre-existing diabetes are:

Care during pregnancy

Care is from the multidisciplinary team, and women will need individualized care according to their own particular health needs. The place of birth should be discussed and should be in a hospital with advanced neonatal resuscitation facilities available 24 hours per day (NICE 2008b). In pregnancy, insulin requirements will be increased to cope with the relative fasting hypoglycaemia, and insulin requirements should be reviewed. Women with type 2 diabetes may also require insulin at this stage. Rapid-acting insulin (aspart and lispro) are considered safe in pregnancy, and of the long-acting insulins, isophane is recommended (NICE 2008b). Oral hypoglycaemics other than metformin are not considered safe in pregnancy. Women should perform their own blood glucose monitoring at home and aim for fasting blood glucose values between 3.5 and 5.9 mmol/L. They should aim to keep 1-hour postprandial (after food) levels below 7.8 mmol/L. Some women find an insulin pump gives better control than multiple injections (NICE 2008b). They should also have ketone testing strips for urinalysis because of the risk of ketoacidosis.

If not already carried out, renal and retinal assessment should be offered. Retinal assessment can be offered again at 28 weeks, or earlier if there are signs of retinopathy. Renal assessment can be followed up by referral to a nephrologist if serum creatinine is raised (120 micromol/L or more), or there is proteinuria >5 g/day (NICE 2008b).

Diet

The carbohydrate energy content of the diet should be related to the energy requirements of the individual. In most cases it does not exceed 40%, but it can be higher without adverse effects. Fat intake should be restricted because of the increased risk of arterial disease in diabetics. A high fibre intake is recommended because the slower gastric emptying delays the absorption of sugar into the bloodstream. Hypoglycaemia may exacerbate the effects of morning sickness; glucose and sugary foods should be avoided, and hypoglycaemia prevented by taking milk and a light snack. Concentrated oral glucose should be available for all women taking insulin, and glucagon for women with type 1 diabetes, in case of hypoglycaemia. Family members should also know when and how to give it.

Diabetes is particularly common in British women of Asian origin. Dietary considerations for such women should avoid sweets, such as gulab juman, halwa and jelabi, and, where the woman is also overweight, foods fried in ghee or oil should be avoided.

Glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1C)

Glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1C) can also be measured every 2–4 weeks, and helps to assess diabetic control. It is a type of adult haemoglobin where one part of the beta chain has been combined with glucose. HbA1C has been found to increase in diabetes, especially when the blood glucose control is poor, although its levels are not indicators of present diabetic status but of blood glucose levels during the preceding 1–3 months. Levels of 10% or lower are considered a sign of good control, while levels of more than 10% indicate poor control (Nelson-Piercy 2006). Women should be offered monthly estimations of HbA1c (NICE 2008b).

Fetal wellbeing

Women should be offered cardiac screening for the fetus at 18–20 weeks, as well as all other usual antenatal screening tests that would be offered at that time. At 28, 32 and 36 weeks, further scans for fetal growth assessment and amniotic fluid volume should be offered (NICE 2008b).

Care during labour

The midwife cares for the woman in conjunction with medical and obstetric colleagues; labour onset may be spontaneous or induced, or delivery may be by elective caesarean section if there are obstetric indications.

In addition to usual care in labour, blood glucose is checked hourly, and the aim is to keep blood glucose levels between 4 and 7 mmol/L. Where this is not possible, or in cases of type 1 diabetes, dextrose/insulin regimens may be used (NICE 2008b).

Electronic fetal monitoring should be continuous because of the increased risks of fetal hypoxia during labour.

Postnatal care

Maternal insulin requirements fall sharply after the birth of the baby and placenta, so frequent blood glucose estimations are made to detect hypoglycaemia. The insulin dosage is reduced and the woman is gradually restabilized.

Breastfeeding should be encouraged, and women may need additional carbohydrate to facilitate this. They may be advised to have a snack before and during feeding, in case they become hypoglycaemic. Infection is an increased risk, so education about good hygiene is important. When women are transferred into the community, they should resume attendance at their regular specialist clinic with routine diabetes care.

Women with type 2 diabetes can resume oral hypoglycaemics, but only metformin and glibenclamide, if they are breastfeeding.

Women with gestational diabetes should stop medication after the birth, and receive information about weight control, exercise, diet, and how to recognize hyperglycaemia. They may also be offered a blood glucose test before transfer into the community, and offered a fasting plasma glucose test at 6 weeks, and then yearly.

Care of the baby

Mother and baby should not be separated unless the baby is ill, and babies should not go home until they are 24 hours old, feeding well, and have stable blood glucose levels (NICE 2008b). These babies are particularly prone to respiratory distress syndrome and hypoglycaemia, so require close observation. In intrauterine life, the hypertrophic islets of Langerhans produce more insulin in response to the high maternal blood sugar levels. After birth, the pancreas continues to produce excess insulin initially, so the baby becomes hypoglycaemic. To prevent this, early feeding within 30 minutes of birth, then 2 to 3 hourly, is essential and the baby’s blood glucose levels are measured 2–4 hours after birth, or earlier if there are signs of hypoglycaemia (NICE 2008b).

Other neonatal complications include skin infections, hyperbilirubinaemia and bleeding from a very thick cord, and the incidence of congenital malformations is increased.

Respiratory problems

Tuberculosis

Pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) is responsible for 6% of all deaths worldwide, and up to half the world’s population is infected with the disease in its latent or active form (Mays 1993, Nelson-Piercy 2006). In the UK, TB is becoming more prevalent, particularly among the homeless, where there is overcrowding, and exposure through contact with people from countries where the disease is widespread. All new UK entrant pregnant women and children younger than 11 years should have a Mantoux test (NICE 2006). Women may become pregnant whilst being treated for TB, or may develop the disease during pregnancy.

Classic symptoms are chronic cough and blood-streaked sputum, with fever, weight loss and night sweats occurring late in the disease. The onset is insidious and there is also a feeling of general malaise.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made when the causative organism (Mycobacterium tuberculosis or the tubercle bacillus) is found in sputum and by chest X-ray.

Pregnancy care

Care in pregnancy should include input by an obstetrician, respiratory physician, GP and midwife, and possibly a social worker if social and economic factors are involved. Help is needed with housework and childcare during and after pregnancy, since the woman will be tired. Liaison with other healthcare workers may be necessary, since family members may need to be screened and educated as to the nature of the disease and the steps needed to prevent its spread.

Infection is spread by airborne transmission of droplet nuclei from a person with active TB, so if the woman is infectious, she needs a single room in hospital.

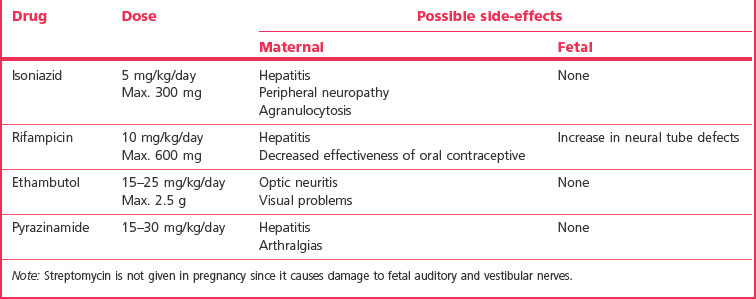

Drugs used to treat TB have side-effects for both mother and fetus; however, treatment in pregancy is safe (Robson & Waugh 2008) (see Table 55.3). Courses of treatment are long – 6 to 9 months or longer – but the symptoms of the disease resolve after only 3 weeks, and the woman will be non-infectious after 2 (Nelson-Piercy 2006). Women must be encouraged to continue treatment, otherwise drug-resistant strains of TB may develop.

In the absence of obstetric indications, labour onset is spontaneous and care is as for normal labour. After birth, the woman should continue treatment. There are no contraindications to breastfeeding. The baby should have BCG vaccination and may have syrup of isoniazid prophylactically. There should be a paediatric review before discharge (NICE 2006). Unless the disease is active, the mother and baby are not separated (Nelson-Piercy 2006).

Advice about family-spacing methods will be needed, as women with active TB should avoid pregnancy until there are no further signs of the disease, usually for a period of 2 years.

Asthma

Asthma is an obstructive disease of the respiratory system characterized by episodic breathlessness, wheezing, cough, thick sputum and feelings of tightness in the chest. It affects 5–10% of the general population and 3–12% of pregnant women (Rey & Boulet 2007). Acute attacks are caused by inflammation, narrowing of the airways, and contraction of the smooth muscle of the airway walls, and are characterized by any one of the following:

An acute attack can be life-threatening, leading to bradycardia, dysryhthmia or hypotension, with exhaustion, confusion, coma and death (BTS/SIGN 2008).

Known factors in asthma attacks are:

There is a complex link between pregnancy and asthma. Some pregnant women experience fewer asthmatic attacks, possibly owing to the increased production of corticosteroids in pregnancy, some may stay the same, but a few may have more, particularly those who have severe asthma. Links have been shown between asthma and poor pregnancy outcomes, including pre-eclampsia, placenta praevia, miscarriage, haemorrhage, and poor placental function, leading to low birthweight. Studies suggest that female gender of the fetus causes a worsening of symptoms in the mother. Causes are unknown but the conditions are less likely to arise where asthma is controlled well (Nelson-Piercy 2006, Rey & Boulet 2007) so it is important to encourage women to maintain their drug therapy.

Drug therapy is often by inhaled anti-inflammatory agents, beta-agonists or steroids. These are safe during pregnancy and midwives should assure women of this. As Nelson-Piercy (2006) points out, poorly controlled asthma carries greater risks for the fetus than do the drugs used to treat it. Women should be advised to use spacers when inhaling steroids to avoid oral thrush, and if they smoke, should be offered help in stopping.

Oral steroids such as prednisolone may be used to control exacerbations; however, these are diabetogenic and women will therefore need regular estimation of blood glucose. Women on oral steroids will need hydrocortisone during labour (Nelson-Piercy 2006). Entonox, epidural and other forms of pain relief can be used in labour; however, opiates are respiratory depressants, and would not be used if the woman had an attack during labour. Epidural anaesthesia is safer for caesarean section, as it avoids the problems of chest infection and atelectasis associated with general anaesthesia.

Breastfeeding is not contraindicated, and may protect the baby from developing atopic asthma (BTS/SIGN 2008, Nelson-Piercy 2006).

Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a condition of abnormal cerebral function causing convulsive seizures. One in 200 people are affected, with an incidence in pregnancy of 0.6–1% (Nelson-Piercy 2006). Seizures may be partial, arising in the frontal or temporal lobe of the brain, or generalized (petit mal and grand mal). Petit mal or ‘absence’ seizures are short (< 20 seconds), while grand mal seizures typically follow a pattern with four phases:

Risks during a seizure are trauma, including biting of the tongue, inhalation of mucus or blood, and cerebral hypoxia. In pregnancy, the fetus is also subject to hypoxia and there may be IUGR. A phenomenon known as sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) can also occur, but may be unrelated to a seizure. In many cases the cause is unknown (idiopathic), but it may follow cerebral trauma, congenital abnormality, space-occupying lesions in the brain, vascular disorders, degenerative disorders, infection, metabolic disorders such as hypoglycaemia, or withdrawal from drugs or alcohol. Seizures may be triggered when women are stressed, tired, in pain, or in hot and steamy environments, and women should be advised about this (Billington & Stevenson 2007).

Status epilepticus is a rare but serious condition in which myoclonic seizures occur in rapid succession. It is controlled by increasing antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), administering diazepam and by intravenous dextrose to prevent hypoglycaemia. CEMACH (Lewis 2007) records 11 deaths related to epilepsy in the 2003–2005 triennium. Six of these deaths were sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). Previous deaths have been due to acccident, drowning in the bath, and aspiration of vomit during seizures. A list of safety measures which may help avoid such accidents is given at the end of this section.

Epilepsy may be controlled, but not cured, by antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), such as phenytoin sodium, phenobarbital, carbamezapine and sodium valproate. All cross the placenta and are teratogenic, and may lead to some major congenital malformations, including neural tube and cardiac defects, with sodium valproate carrying the greatest risk and carbamezapine the least. Abnormalities occur more often in women who receive combinations of AEDs (polytherapy), so, during pregnancy, monotherapy is recommended. However, about 96% of women will have a normal baby (Morrow et al 2006). Pregnancy has a variable effect on seizures: some women will have fewer seizures and about a third will have more (Epilepsy Action 2006). The aim is to be as seizure-free as possible. Physiological changes in pregnancy result in lower concentrations of AEDs, which may need to be increased. These drugs alter the absorption of folic acid and 5 mg/day should be given as a prophylactic precaution pre-conception and during the first trimester, and throughout pregnancy for women taking sodium valproate. For the same reason, clotting factors may be inhibited in both mother and baby. Women may be given 10–20 mg/day vitamin K orally for 4 weeks from 36 weeks, and babies should receive 1 mg vitamin K intramuscularly post delivery (Epilepsy Action 2006, Nelson-Piercy 2006).

In the absence of obstetric complications, labour and delivery will be spontaneous, and midwifery care as for any woman in labour. Pain relief can include TENS, Entonox or epidural, and overbreathing should be avoided as this can trigger seizures, as can pethidine. It is important to make sure women continue to take their AEDs.

All AEDs are secreted in breast milk, but there is no contraindication to breastfeeding.

Individualized parenting programmes can help women and their families keep healthy and safe during pregnancy and after the birth. Advice for the woman may include the following:

More information can be found on the Epilepsy Action website (www.epilepsy.org.uk).

Obstetric cholestasis

Obstetric cholestasis (formerly known as intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy) is a disease arising in the third trimester which is characterized by intense pruritus (itching) without a rash, abnormal liver function tests (LFTs), dark-coloured urine, anorexia, malabsorption of fat and elevated maternal bile acid levels. It is thought to arise from a genetic hypersensitivity to oestrogen and is associated with increased rates of fetal mortality and morbidity, and with maternal coagulation defects, due to inability to absorb vitamin K, which is fat-soluble (Nelson-Piercy 2006). It occurs in 0.7% of pregnancies in multi-ethnic populations, with a higher incidence (1.2–1.5%) in women of Indian-Asian or Pakistani-Asian origin (RCOG 2006). The condition was once thought to be benign, but it is now recognized that it may be a factor in ‘unexplained’ fetal deaths, some of which are sudden, and are almost impossible to predict. It is thought that bile acids cause placental vasoconstriction, resulting in fetal hypoxia. In up to 40% of pregnancies complicated by obstetric cholestasis, there will be meconium in the amniotic fluid, with the risk of meconium aspiration (Redfearn & Chambers 1996).

Any woman complaining of severe itching, which often begins on the palms of the hands, should be referred for liver function tests. If obstetric cholestasis is diagnosed, careful monitoring is required to detect and prevent coagulation defects by giving vitamin K. Fetal wellbeing is monitored, checking growth, liquor volume and blood flow, using Doppler studies. Early delivery has not been shown to decrease the risk of perinatal mortality (RCOG 2006).

The most distressing aspect of the condition for women is the interruption of sleep because of itching. Antihistamines such as promethazine (Phenergan) may be given to alleviate itching, and women should be encouraged to wear loose cotton clothing. Topical applications of calamine lotion or aqueous cream may also help.

Although symptoms will disappear following delivery, the risk of recurrence in subsequent pregnancies is as high as 50%. Since the condition is related to oestrogen, women should avoid oral contraceptives containing oestrogen (Nelson-Piercy 2006).

Conclusion

This chapter has reviewed some of the medical disorders midwives may encounter when working with pregnant women. Whilst pathophysiology and practical care are important, emphasis must also be placed on the need to treat women as individuals, and not merely a reflection of their condition. The midwife has an important role in identifying women with pre-existing medical conditions, and women who may be at risk of developing such conditions, and in monitoring the wellbeing of the woman and her baby throughout. The need to educate and support women and involve them in planning and participating in their care will ensure that even should intervention be required, complications and problems should be minimized and the women will feel empowered during the process.