Chapter 61 Procedures in obstetrics

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

Introduction

A baby may enter the world spontaneously through the mother’s vagina, with only the occasional need for guidance from attendants, by operative means with the use of forceps, vacuum extraction, or by caesarean section. Yet rates for normal birth have seemingly fallen over the previous two decades. The Healthcare Commission review of the maternity services (Healthcare Commission 2008) revealed normal birth rates in maternity units are as low as between 32% and 40%. Whilst there are some areas where home births are increasing and despite admirable drives by a small number of celebrities, many midwives and various pressure groups, instrumental delivery rates continue to increase annually along with caesarean sections. It might be considered that, soon, spontaneous vaginal delivery will no longer be the accepted normal route.

The following chapter explores some of the issues for midwives within the trends of increasing operative deliveries, including the impact that this can have on women’s and children’s health. The sections on instrumental and caesarean style deliveries will begin with the morbidity associated with them. Indications for each type of delivery will be listed, followed by a brief exploration of aspects of care given to the woman in labour that may have the potential to increase the need for an instrumental or an operative delivery. The midwife’s role in providing the most effective and appropriate care for any woman undergoing an instrumental or an operative delivery will be discussed.

Operative vaginal deliveries

Forceps and ventouse extraction have the potential to safely remove the infant and mother from a hazardous situation (Dennen & Hayashi 2005), and even to save lives. Taking this into consideration, however, the increase in their use has an impact on the health of women and their babies. Highest rates of trauma are consistently observed with operative procedures, with short-term and long-term morbidity.

Neonatal complications

After any instrumental vaginal delivery, the baby may suffer hypoxia, have lower Apgar scores and require appropriate resuscitation. Facial or scalp abrasions or bruising are common. A cephalhaematoma may develop because of friction between the fetal head and pelvis or forceps blade, as well as from the suction of the ventouse cup. There may be an increase in jaundice due to reabsorption of haemoglobin associated with this bruising (Dennen & Hayashi 2005). Facial palsy, which is usually temporary, may occur owing to the compression of the facial nerve which runs anteriorly to the ear, by the forceps blade. Intracranial trauma and haemorrhage is higher amongst infants delivered by vacuum extraction, forceps or caesarean section (Towner et al 1999). In more rare circumstances, tentorial tears and rupture of the great vein of Galen may occur, leading to bleeding and compression of the brainstem. Skull fractures are usually linear but occasionally a depressed fracture can result in a subarachnoid haemorrhage. Kielland’s forceps can cause unexplained convulsions. Retinal haemorrhages are more common in vacuum extraction deliveries (Vacca 1996). The most serious complication to occur is that of subgaleal haemorrhage.

Maternal complications

The most common injuries to the genital tract are cervical, vaginal and perineal tears, haematomas and rectal lacerations (see Ch. 40). Bladder or urethral injury may occur, causing urinary retention and even the formation of a fistula. Perineal pain due to bruising, oedema, trauma and episiotomy can impair sexual function and infant feeding. Pelvic floor disorders and long-term pelvic floor morbidity are strongly associated with instrumental delivery (Bahl et al 2005). There is an increased risk of haemorrhage (Walsh 2000). A rare complication is that the cervix and lower segment of the uterus may be damaged.

The psychological effects of instrumental delivery may include fear and anxiety in relation to subsequent pregnancy, and feelings of failure, inadequacy and disappointment. Both forceps and ventouse-assisted deliveries were found to be predictive factors of acute trauma symptoms and post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of women’s birth experiences (Creedy et al 2000). Jolly et al (1999) concluded that caesarean section and vaginal instrumental birth are associated with voluntary and involuntary infertility as many mothers may be left with fearful feelings about future childbirth: 13% more of women who had a caesarean section and 6% more of those who had instrumental births had not had a second child compared with those following normal birth.

Reflective activity 61.1

Owing to the maternal and neonatal morbidity associated with instrumental deliveries, it appears appropriate for all midwives to reflect in and on their own practice to ensure that aspects of care for women in normal labour are not increasing the possibility of operative deliveries. Take time to explore your beliefs regarding the points for midwifery practice below. Each time you care for a woman who requires an instrumental delivery or an emergency caesarean section, reflect upon the course of her labour to assess whether there were any aspects of her care that may have contributed to the outcome. Record your thoughts for future reference.

Key aspects of midwifery practice

Some critical consideration of aspects of care may enable the midwife to plan care to ensure the woman’s comfort and safety and also to reduce the need for intervention and augmentation. This has wide-ranging implications for the quality of care and for effective use of both human and other resources within the service. It is also crucial that the midwife work in partnership with the woman to ensure that she is informed and fully prepared for the labour and birth.

Policies

Blanket policies to treat prolonged labour and ‘failure to progress’ should be examined as there is much literature available to explore long-held beliefs of the definition of the duration and progress of labour. Even in 1973, when medicalization was really taking control of childbirth, Studd (1973) questioned the arbitrary application of time limits on labour considering the confusion over the diagnosis of the onset of active labour. Yet this confusion remains and time limits for stages of labour remain in place.

Position for labour and delivery

An upright position, preferably mobile, assists the woman to feel in control, can reduce her distress and help her to adopt comfortable positions more easily. During a review of trials for The Cochrane Library, Gupta & Nikoderm (2001) highlighted that adopting upright positions in labour appeared to reduce the number of assisted deliveries and fewer abnormal fetal heart rate patterns were noted (see Chs 36 and 37).

Diet, fasting and nutrition

Fasting women throughout a normal labour can add to exhaustion, as labour is a time of great energy demand and it is estimated that a labouring woman may require 800–1100 kcal/hour (Ludka & Roberts 1993). Whilst women adapt to a small rise of ketones in labour, blood pH can be reduced in starving women and result in ketoacidosis. Even as far back as the 1960s, Mark (1961) discovered that uterine activity was influenced by environmental pH and that myometrial cells spontaneously contract with increased alkalinity, preferably between 7.8 and 7.1. Ketones that build up may also cross the placenta, and if there is an accumulation in the fetus, this can affect fetal wellbeing and fetal activity (Swift 1991).

Supportive presence during labour

A Cochrane review highlights that the presence of an appropriate support person throughout labour is associated with a decreased incidence of epidural anaesthesia, dystocia and instrumental deliveries (Hodnett 2001).

Amniotomy and Syntocinon

Amniotomy can increase the requirement for instrumental delivery and caesarean section (Johnson et al 1997). It is recognized that amniotomy causes fetal heart abnormalities owing to cord and head compression, which then increases the risk of interventions. It can inhibit the rotation of some malpositions – for example, occipitoposterior positions – which may predispose to delay. There is an increase in pain during contractions, which may, in turn, increase the demand for epidural analgesia. Syntocinon reduces the oxygen supply to the baby’s brain. The fetus may then display signs of fetal distress, increasing the need to dramatically shorten the labour (O’Regan 1998).

Pain relief

Epidurals are associated with a substantially increased use of assisted vaginal delivery (Mander 1994). Epidurals increase the length of the first and second stages, often affecting the efficacy of contractions, increasing the need for Syntocinon (Page 2000).

Indications for the use of assisted vaginal delivery

The following short list is not absolute but meant to give a general idea of the most common indications for the use of forceps or vacuum extraction during the second stage of labour:

If an instrumental delivery is necessary

The woman and her companion are likely to be extremely apprehensive once the need for an instrumental delivery is recommended. When the midwife has summoned the appropriate personnel, who will preferably include a senior obstetrician, a paediatrician and another person who can assist with assembling equipment, there will be several strangers in the room. Midwives then have to prioritize the care they give and, where possible, involve other members of the team to assist the doctors rather than leave the woman’s side. Midwives must remember that they remain the woman’s advocate and must be present to explain all the procedures, support, encourage and ensure that there is a respectful environment within the delivery room. There should be little discussion in the room that does not include the woman.

Procedure

Prior to the delivery, the mother is helped into the lithotomy position. The midwife must ensure that the woman is covered with a sheet as much as possible and for as long as possible, to protect her dignity. Both legs are flexed simultaneously and gently onto the abdomen, and the feet moved to the outer sides of the supports and placed in the leg rests or stirrups together to avoid sacroiliac strain. To prevent obstruction of venous return and possible thrombosis by pressure, care is taken to ensure that the legs are fully abducted. Once the mother is correctly positioned, the foot part of the bed is lowered and the mother’s buttocks lifted to the edge of the bed. The operator can now proceed.

Ventouse vs forceps

Debate exists over the preferred instrument for vaginal delivery once it is believed to be necessary. There are two methods for instrumental delivery: forceps and vacuum (ventouse) extraction. A Cochrane systematic review of nine randomized controlled studies involving 2849 primiparous and multiparous women compared vacuum extractions with forceps. Ventouse appears to be significantly more likely to fail at achieving a vaginal delivery, but is less likely to produce maternal trauma and less likely to be associated with severe perineal pain. However, it does produce increased rates of cephalhaematoma, retinal haemorrhages and low Apgar scores at 5 minutes. There appeared no difference in long-term outcome between the two instruments (Johanson & Menon 2000).

Forceps

Forceps were first described in 400 BC by Hippocrates to extract dead fetuses. From a birthroom scene on a marble relief, it would appear that forceps were also used in Roman times, but in modern history the use of forceps as an aid to vaginal delivery has been known only since their invention by the Chamberlen family in the 1600s (Pearson 1981). The family tried to keep the nature of their instruments a secret, as these forceps offered a practical possibility of live births from obstructed labours and were a source of fame and money to those who used them.

Since the introduction of forceps, many attempts have been made to improve the efficacy and safety of the instrument for specific obstetrical situations and the shortcomings of current forceps design is acknowledged. In fact, the blades of some designs were designed for delivery of the long ovoid moulded head, which was a common shape adapted from prolonged labour. As a result of present-day care, this shape is less frequently seen and the head is less moulded and more spherical (Hibbard 1989).

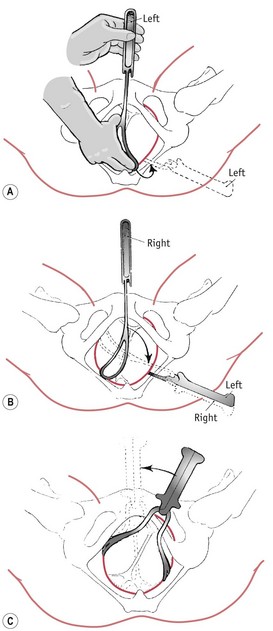

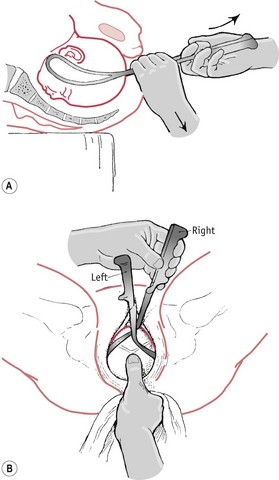

Forceps may be used in two ways: to exert traction without rotation; and to correct malposition, for example, occipitoposterior position, by rotation prior to traction. Rotation is rarely performed now owing to the trauma to the mother and the baby (Figs 61.1 and 61.2). There are definitive texts available (see website) which outline the procedures for forceps delivery, but here it would appear more pertinent to discuss certain principles for all types of the delivery.

Vacuum extraction

Vacuum extraction is a method of instrumental delivery which involves the use of a vacuum device as a traction instrument to assist delivery. The technique was developed from early work by Young, a Royal Navy surgeon in 1705, and Simpson in the 1840s (Chamberlain 1989). The modern version was developed by Malmstrom in the 1950s.

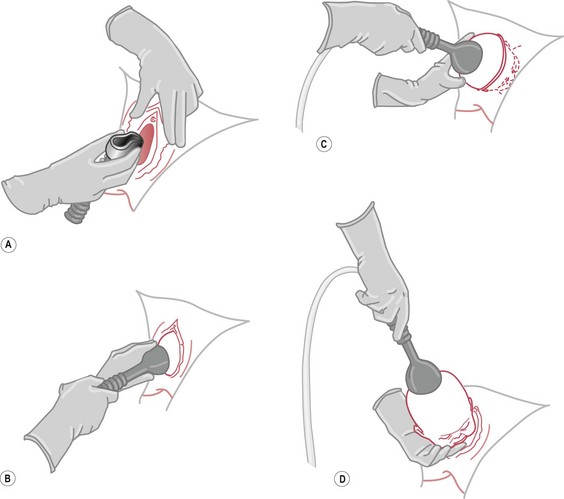

The vacuum extractor or ventouse consists of a cup made of metal or soft material, such as silicone rubber, a traction device and a vacuum system providing negative pressure, by which the cup is attached to the fetal scalp. For equipment and procedure, see Figure 61.3.

The cups were originally metal, but the softer caps which have been available since the early 1980s are proving more popular. Previously, the metal cup formed a ‘chignon’, but now the soft cup relies on covering a larger surface area in order to develop sufficient traction, and this has led to less scalp trauma.

Contraindications specific to ventouse and in addition to those listed above for all instrumental deliveries are:

Postnatal care

At delivery, if the baby’s condition permits, he or she should be given to the mother immediately. If resuscitation is required, then as soon as the condition is satisfactory, the baby should be given to the mother with relevant explanation for any necessary procedures that were undertaken. If the baby is transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit, then the parents must be kept informed of the baby’s condition and taken to visit as soon as possible. Once the doctors have left, the midwife should ensure that the parents have a quiet and protected time to recover and develop a relationship with their baby.

Postnatal observations will be as for any delivery, but particular attention should be paid to pain from perineal trauma, urinary output in case any damage has occurred to the bladder, and signs of postpartum haemorrhage due to uterine atony and trauma. Particular requirements may include analgesia and assistance with feeding owing to discomfort. It is also important to observe the neonate for any sign of trauma, and ensure that a thorough, careful examination is carried out, with appropriate referral should any deviations from the normal be noted. Owing to the possible link discussed earlier with acute trauma symptoms and post-traumatic stress disorder, there must be an opportunity for the midwife to review with the woman, her experience, and discuss any concerns regarding the intervention and the procedure with the parents. It is also an appropriate time to ensure that the woman is assured that she did not ‘fail’.

Caesarean section

Caesarean section is the delivery of the fetus, placenta and membranes through a surgical incision in the abdominal wall and uterus. There are two types of caesarean section:

The increasing caesarean section rate in the UK is attributed to a variety of causes in varying sources of literature. These include delivery of preterm infants now likely to survive with good neonatal care, avoidance of litigation, lack of staff on maternity units, maternal request, increased medicalization of childbirth, increased induction rate, and individual obstetrician’s preferences in their practice. The Sentinel study also illustrates that the caesarean rate is raised in older women, black African or Caribbean women, previous caesarean section, and breech presentation and multiple pregnancy (Thomas & Parenjothy 2001) (Table 61.1). It was suggested that in all of these categories, there may be an increased risk of complications requiring such intervention.

Table 61.1 Indications for caesarean section

| Indications | Caesarean section rate |

|---|---|

| Fetal distress/abnormal CTG | 22% |

| Failure to progress/induction | 20.4% |

| Previous caesarean section | 13.8% |

| Breech position | 10.8% |

| Maternal request | 7.3% |

| Malpresentations | 3.4% |

| Placenta praevia/bleeding | 2.2% |

| Pre-eclampsia/eclampsia/HELLP | 2.3% |

| Multiple pregnancy | 1.2% |

Caesarean section is a major surgical procedure and, in a small number of cases, it can save both neonatal and maternal lives, improve outcome for some babies who may have undergone extended labour, and reduce the potential risks of infection associated with some vaginal deliveries (Duff 2000). Nevertheless, though the caesarean section rates have significantly increased, maternal and neonatal mortality do not appear to be decreasing and, indeed, neonatal and maternal morbidity is increasing. Hillan (2000) realized from available figures that 9–15% of women delivered by caesarean section suffer serious maternal morbidity, whilst another 65% did not feel fully recovered until 3 months after caesarean section.

There is a plethora of literature highlighting the morbidity and the increased risk of mortality associated with caesarean section. Physical effects range from tiredness, backache, sleeping difficulties and depression, to wound and urinary tract infection (Hillan 2000). There is an increased risk of haemorrhage, thromboembolism, peripartum hysterectomy, future miscarriages, ectopic pregnancies, placenta abruptio and praevia, and reduced fertility (Wagner 2000). Some mothers experience a sense of loss or failure because they have been unable to deliver their baby vaginally. Psychological effects of caesarean section include extreme disappointment, intense anxiety, and a sense of inadequacy and failure, and may include acute trauma symptoms or post-traumatic stress disorder as previously associated with instrumental delivery (Creedy et al 2000). There appears little difference between emergency or elective surgery.

Risks of caesarean section to the fetus

Owing to maternal cardiovascular changes, especially with spinal anaesthesia, low Apgar scores and relative fetal acidosis may occur. Later, respiratory distress may develop, which is usually due to transient tachypnoea of the newborn (see Chs 41 and 45), the incidence being four times greater in babies delivered by elective caesarean section than in those who are delivered vaginally. This is thought to be due to the lack of catecholamines being produced by the mother, which would normally cross the placenta and ‘switch off’ the production of lung fluid by the fetal lung pneumocytes. It was thought that at birth there was an excess of up to 30 mL of fluid which may not have been absorbed by the lymphocytes, or by ‘vaginal squeezing’ as would happen during a vaginal birth, and therefore the neonate needs to cry lustily at birth to assist the absorption of this excess lung fluid (Strang 1991). However, it is now thought that there is only about 35% of this fluid at term, and that it is absorbed through the lymphatics and changes in the pulmonary blood flow (Blackburn 2007), and that the vaginal squeeze has a minor effect on fluid clearance.

Annibale et al (1995) concluded in their study that abdominal delivery following an uncomplicated pregnancy remains a risk factor for adverse neonatal outcome. During a conference in 1999 entitled The rising caesarean section rate: a public health issue, a neonatologist came to the conclusion that babies should only be born by caesarean section if they are very large, in a difficult position or known to have a mother with a serious viral condition such as HIV (Duff 2000).

Indications for caesarean section

Examples of some indications for caesarean section include the following:

Implications for midwifery practice

Whilst the majority of the list above appears appropriate for caesarean section, there is an increase of caesarean section due to ‘failure to progress’ and fetal distress. It would be advantageous now to revisit the areas discussed earlier in relation to instrumental delivery as they are also relevant to caesarean section. Additional points to be considered include:

Midwife’s role

Whether surgery is an emergency or elective procedure, the midwife should ensure that the woman understands the reasons for surgery and that a written consent form is obtained for the operation.

A sample of venous blood must be collected for full blood count, haemoglobin level and cross-matching. The woman should be dressed in a theatre gown and wearing identification labels. Antiembolic (TED) stockings should be applied. It is preferable that the woman is not wearing any make-up to ensure that the anaesthetist can observe her colour, that jewellery is taped or removed for safety reasons because of the use of diathermy during the procedure, and that her pubic area has been shaved, removing as little as absolutely necessary for the incision.

In theatre

Along with the usual theatre staff, a paediatrician will be present for each case and the midwife will usually assist at the resuscitaire after receiving the baby at delivery. It is preferable that the anaesthetist can meet, examine and discuss any procedures with the woman prior to the surgery, although this may not be possible in emergency circumstances. The anaesthetist will be fully involved with the woman once in theatre but the midwife should remain with her and her partner as support for both of them. Operating theatres can be quite frightening areas to be in. The fetal heart will still require frequent auscultation, and this must be recorded.

Anaesthesia

General anaesthesia in obstetric women is fraught with difficulties. One of the complications which may occur during anaesthesia is acid aspiration syndrome, which may be reduced through cricoid pressure during intubation (see website for more detailed information). The problems also include raised maternal intragastric pressure; acidity of gastric contents; aortocaval occlusion if the supine position is employed; the adverse effects on the fetus of the drugs used, or of maternal hypoxia or hypotension; placental insufficiency; and intrapartum fetal hypoxia. These problems are exacerbated in the case of preterm infants, or in the woman whose condition is poor, that is, if she is eclamptic.

Intubation in the pregnant woman may be difficult because of the posture of the neck in pregnancy or laryngeal oedema in cases of pregnancy-induced hypertension.

To minimize the risk of supine hypotensive syndrome, the operating table is tilted laterally, or the woman is wedged at a lateral tilt until the infant is delivered. A foot cushion is usually employed to elevate the legs from the table to avoid venous stasis in the calf muscles; other means, such as TED stockings, should be used to avoid the risk of venous thrombosis. The bladder will be emptied and a catheter inserted which will remain in place during the procedure. The fetal heart will be listened to prior to surgery.

Spinal (subarachnoid) and epidural anaesthesia

Many caesarean sections are now performed under epidural or spinal, rather than general, anaesthesia (see Ch. 38). This removes the risks associated with general anaesthesia and enables the mother to see and hold her baby at birth. It is reported that this method is superior in facilitating the mother–baby relationship. The partner may be present so that he can be supportive to the mother and share in the experience.

This text is inappropriate for discussion of either epidural or spinal anaesthesia in depth and the reader is recommended to visit anaesthesia textbooks to explore the technicalities further.

Immediate postoperative care

If the woman is awake, the midwife should ensure that the baby is shown to her as soon as possible. If the baby does not require resuscitation following delivery, opportunity for the mother to hold and touch her baby as soon as possible should be actively encouraged (see below).

In the immediate postoperative recovery period, regardless of the method of anaesthesia, pulse, blood pressure, respirations, colour, state of consciousness, vaginal loss, wound dressing, catheter and wound drainage are observed, as appropriate. If the woman has had a general anaesthetic, extubation is performed. This involves removal of the endotracheal tube once reflexes have returned, suction is carried out and the operating table is tilted head down. Vigilance at this stage is important as the woman may not be fully conscious and inhalation of gastric contents may still occur. The woman is placed on her side to maintain the airway, assist drainage of secretions and prevent airway obstruction by the tongue.

Infusion of intravenous fluids is monitored and recorded on the anaesthetic sheet. An analgesic may be administered for pain relief. When the woman’s postoperative condition is satisfactory, the anaesthetist will give permission for her to be discharged to the care of the ward staff. Instructions and details of the surgery and anaesthetic are recorded in the notes and given to the receiving midwife.

Maternal–infant attachment

The baby is received by the midwife and any resuscitative measures are carried out by a paediatrician, or by a midwife skilled in neonatal resuscitation. However, if the mother is conscious and the baby appears well at birth, the baby should be given to the mother immediately. There are many maternity units now that actively encourage breastfeeding in the theatre if the mother wishes it, and skin-to-skin contact if it is safe and convenient so to do. A preterm or ill baby will be admitted to the neonatal unit for special or intensive care. The parents will naturally be very anxious if their baby requires such care and should be encouraged to visit as soon as possible. The neonatal unit staff often take photographs of the baby to give to the parents when visiting is difficult.

Record keeping

Accurate and contemporaneous records are made of all observations and treatments. The midwife responsible for the care of mother and baby will give a detailed handover report to the ward midwife. This report will include the condition of the mother and the baby at birth, including the care and any treatment given before transfer to the ward or, in the case of a sick or preterm baby, to the neonatal unit. This information will enable all staff involved with the mother and baby during the early postnatal period to give appropriate care and support.

Postnatal observations

There is a high risk of postpartum haemorrhage, adding to the amount of blood lost during the operation. The uterus may not contract effectively and there is the very serious complication of the unsuspected continuation of intraperitoneal bleeding after the operation. The following observations and care routines are guidelines only, but denote safe and best practice:

Trial of scar – vaginal birth after caesarean section (VBAC)

There are many different rates of successful vaginal birth reported after caesarean section. Dickinson (2005) gave the results of two studies undertaken in the last decade: one, by Flamm, included 5022 women and revealed a 75% vaginal birth rate; the other was by Miller, who reviewed 12,707 trials of labour and reported an 82% successful vaginal birth rate. The indication for the previous caesarean section should, of course, come into consideration.

There is no evidence to support the policy of some hospitals that these women should have an intravenous cannula sited and continuous electronic fetal monitoring once labour has commenced. There is also debate regarding place of birth, some opting for home birth and others in hospital. This has to be considered individually with each woman. As in all labours, close observations of maternal and fetal condition are made, especially noting any tenderness or pain over the caesarean scar. The other signs that may occur include signs of abnormal uterine action, signs of maternal haemorrhage and acute fetal bradycardia. (For cervical cerclage, please see website.)

Conclusion

The number of normal physiological births appears to be decreasing in the UK, whilst figures for caesarean section and instrumental deliveries are rising, with increasing neonatal and maternal morbidity and static mortality (Thomas & Parenjothy 2001). This rise may cause an eroding of the midwife’s role, skills and knowledge, with an associated lack of confidence in the ability of midwives to care for physiological birth. In this climate, midwives should reflect upon their own practice and make continuous professional and practice development part of their work. Nevertheless, there are still a significant number of women who will require an operative-style delivery and they require the midwife’s unique skills and understanding in addition to ‘normal’ postnatal care. Midwives must ensure that they provide appropriate and relevant care tailored to each individual woman to minimize the associated morbidity.