Chapter 59 Multiple pregnancy

The Incidence of Multiple Births

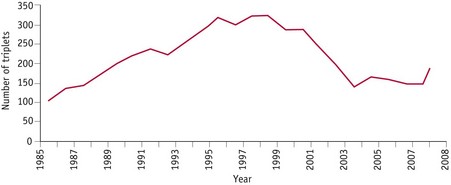

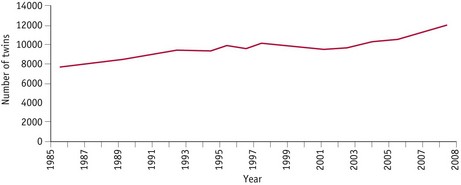

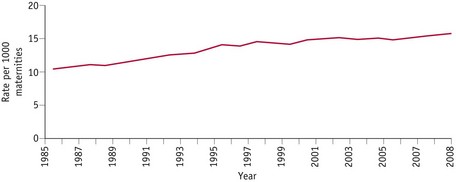

The incidence of multiple births continues to rise, mainly because of the increased availability of treatments for infertility (Kurinczuk 2006). A decline in the 1970s was followed by a rise from the early 1980s onwards (Fig. 59.1) (MacFarlane & Mugford 2000). In the UK, the multiple birth rate in 2008 was 15.48 per thousand maternities (Fig. 59.2). A total of 11,573 sets of twins and 149 sets of triplets were born (Fig. 59.3).

Figure 59.1 Twinning rate in UK 1985–2008.

(Source: ONS London, GRO Northern Ireland and GRO Scotland.)

Figure 59.2 Multiple births in England and Wales, 1985–2008.

(Source: ONS, Birth Statistics, Series FM1.)

Multiple pregnancies carry higher risks for the mothers and babies, and can impose a greater burden practically, financially and emotionally on the parents (Botting et al 1990) and also on neonatal services (Collins & Graves 2000).

The rate of conception of multiple pregnancies is almost certainly higher than the recorded data suggest. Early ultrasound scans have shown that although there may be two or more fetal sacs in the first few weeks, some fetuses may die during the first trimester. This is described as ‘the vanishing twin syndrome’ (Landy & Nies 1995). If a multiple birth occurs before 24 weeks’ gestation and includes both live births and dead fetuses, the fetal deaths are not registerable.

If a dead fetus is delivered with a live birth after 24 weeks’ gestation, it should be registered as a stillbirth even if death occurred much earlier in the pregnancy (MacFarlane & Mugford 2000).

Facts about multiples

How twins arise

There are two types of twins: monozygotic and dizygotic.

Causes of twinning

The cause of monozygotic twinning is unknown, but recent reports suggest that slightly more are born after the use of drugs to stimulate ovulation and assisted conception procedures. The incidence of MZ twins throughout the world was approximately 3.5–4 per 1000 until the recent slight rise which may be associated with fertility treatments (Derom et al 2001).

Dizygotic twinning is different as there are several known associated factors (Chitayat & Hall 2006): maternal age, parity, race, maternal height and weight, and infertility treatments.

Determination of zygosity

Zygosity determination means finding out whether or not twins, triplets or more are monozygotic (identical). Midwives should understand the importance of this for the clinical care of the mothers and babies, so that it is not incorrectly assumed that, if the babies are the same sex and dichoronic, they are necessarily dizygotic (non-identical) (see placentation above). Accurate information about zygosity and how it can be determined should be provided as soon as a multiple pregnancy is diagnosed.

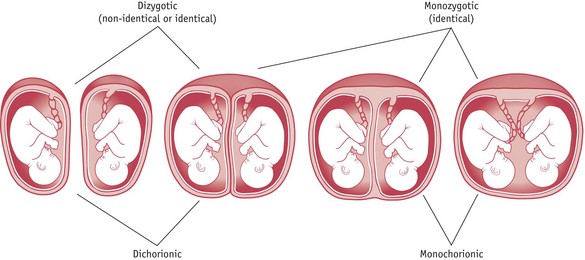

Placentation

There can be two separate placentas (dichorionic) or a single placenta (monochorionic), which can sometimes be fused (dichorionic) (Fig. 59.4). All dizygous twins have dichorionic (two chorions) and diamniotic (two amnions) placentas (DCDA).

About one-third of monozygous twins also have DCDA placentas; this arises if the embryo divides within the first 3 or 4 days after fertilization, before implanting in the uterus. In about two-thirds of cases, the division occurs between 4 and 8 days and this placenta will be monochorionic diamniotic (MCDA). Monoamniotic twins (MCMA) occur in about 1% of cases and arise when the embryo divides later, between 9 and 12 days.

Despite the now well-established facts about placentation and zygosity, many parents are still told incorrectly that if same-sex twins are dichorionic they must be non-identical.

Importance of chorionicity

When a twin pregnancy is diagnosed on ultrasound scan, an assessment of the chorionicity should be made (preferably during the first trimester) by measuring the thickness of the dividing membranes (Fisk & Bryan 1993). Nearly all monochorionic placentas have blood vessels linking the placenta together. As long as the bloodflow can pass in both directions, there will not be a problem; however, if anastomoses occur between an artery and a vein, causing the blood to flow in one direction only, twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome is likely to occur. This happens in approximately 15% of MCDA twins.

Zygosity determination after birth

DNA testing

The most accurate method of zygosity determination currently is to compare DNA (see The Multiple Births Foundation website: www.multiplebirths.org.uk).

Diagnosis of a multiple pregnancy

Ultrasound examination

Ultrasound screening may be carried out as early as 6 weeks into the pregnancy and most women are aware of the multiple conception by 20 weeks. When the diagnosis is made in the first trimester, the risk of the ‘vanishing twin syndrome’ should be explained (Landy & Nies 1995). Chorionicity should be determined in the first trimester.

Inspection

A midwife must always be alert to the possibility of twins if, on inspection, the uterus looks larger than expected for the gestation, especially after 20 weeks, and fetal movements are seen over a wide area, although the diagnosis need not always be of twins. A history of twins in the family should also be taken into account.

Palpation

On abdominal palpation, the fundal height may be greater than expected for the period of gestation.

If two fetal poles (head or breech) are felt in the fundus of the uterus and multiple fetal limbs are palpable, this may be indicative of a multiple pregnancy. A smaller-than-expected head for the size of the uterus may suggest that the fetus is small and there may be more than one present. Location of three poles is diagnostic of at least two fetuses.

Auscultation

Hearing two fetal heart rates is not diagnostic of a twin pregnancy, as one heart rate can be heard over a wide area. The use of ‘Sonicaid’ machines in monitoring fetal heartbeats has improved detection of more than one fetal heart rate, but heartbeats must be listened to simultaneously for at least 1 minute. If the two heartbeats have a variation of more than 10 beats per minute, almost certainly twin infants are present.

Antenatal screening

The UK National Screening Committee standard for screening in multiple pregnancy is by measurement of nuchal translucency (NT), preferably in combination with biochemistry. Biochemical screening alone should not be used.

Chorionic villus sampling (CVS) can be performed from the 11th week and has a 3–4% risk of miscarriage in a multiple pregnancy. Amniocentesis can also be performed in twin pregnancies, usually between 15 and 20 weeks. The risk of miscarriage is 2.5%. Both tests should be performed in a specialist fetal medicine centre.

Antenatal preparation

Early diagnosis of multiple pregnancy and chorionicity is extremely important so that parents have the additional specialist support and advice they need.

At whatever stage parents are told, it is essential that whoever shares the news is aware of the effect the revelation may have. Although some mothers and fathers are delighted to know that more than one baby is expected, in many cases there are reactions of shock and disbelief (Spillman 1986). It is important that an obstetrician or midwife is available to answer questions and give appropriate counselling at this time. It is helpful if the mother can be put in touch with other parents of twins who can understand and provide reassurance. Contact numbers for local twins groups and information about other relevant support organizations can be a great source of reassurance (see website).

Parent education

As soon as a multiple pregnancy is diagnosed, written information should be given containing contact numbers of the local twins club, the parent education department at the local hospital, and national twin organizations, such as The Multiple Births Foundation (MBF) and The Twins and Multiple Births Association (Tamba). The news that two babies are expected can come as a considerable shock to some families, and the midwife should give them every opportunity to discuss any concerns they have.

Routine parentcraft classes need to be booked as early as possible; ideally, the mother should commence these at 24 weeks’ gestation, which is earlier than for a singleton pregnancy, or specialist multiple pregnancy classes at 28 weeks (Davies 1995). When planning classes, contact with the local twins club can provide a very useful source of practical information. Mothers from twins clubs are usually delighted to participate and offer practical information, such as on equipment, clothes and breastfeeding (Denton & Bryan 1995).

The aim, as for all pregnant women, should be for continuity of care throughout the pregnancy. Multiples are considered high-risk pregnancies; if dedicated ‘twin clinics’ are held, these midwives specialize in the care of women expecting twins or more and offer the specific care, continuity and support needed.

Midwives must be aware of the enhanced role of fathers in the care of multiples and their cooperation in the mother’s care should be sought from the start.

Preparation for breastfeeding

Mothers expecting twins or triplets will inevitably give a lot of thought to how they are going to feed their babies, not only from the nutritional aspect but also from the practical one because feeding will take a large part of the first months. Mothers should be encouraged that breastfeeding not only is possible for two babies and in some cases three (Fuducia 1995), but can be a very rewarding experience for all. Breast milk is ideal for all babies and especially important because twins, and more so triplets, tend to be born prematurely and of low birthweight.

Early in the pregnancy the mother should be given as much information about breastfeeding as possible, with contact numbers of local breastfeeding organizations. Both parents should have the chance to talk through any issues; a good idea is to suggest they meet with another mother who is successfully breastfeeding twins (see Davies & Denton 1999).

Complications associated with a multiple pregnancy

When the pregnancy is multiple, minor disturbances are likely to be exaggerated. Morning sickness is often severe and prolonged. Heartburn can be persistent. Increased pressure may cause oedema of the ankles and varicose veins in the legs and vulva. As the pregnancy progresses, dyspnoea, backache and exhaustion are common.

More serious complications

Fetal abnormalities associated with monozygotic twins

Conjoined twins

This results from the incomplete monozygotic division of the fertilized ovum. It is extremely rare, occurring in approximately 1.3 per 100,000 births. Delivery has to be by caesarean section; separation of the babies is sometimes possible, depending on which internal organs are involved.

Acardiac twins (twin reversed arterial perfusion, TRAP)

In acardia, one twin presents without a well-defined cardiac structure and is only kept alive through placental anastomoses to the circulatory system of the healthy co-twin (Moore et al 1990).

Fetus-in-fetu (endoparasite)

In fetus-in-fetu, parts of a fetus become lodged within the other, usually healthy, twin. This can only happen in monozygotic twins and is seen equally in both sexes (Baldwin 1994).

Intrapartum care

It is advisable that all mothers expecting a multiple birth be booked for delivery in a consultant unit. Ideally, in the case of triplets and higher-order births, this should be a hospital that can offer intensive neonatal care facilities, such as a regional referral unit.

Complications

The risks during labour to mother and babies is much greater in a multiple pregnancy. As well as preterm delivery, other complications are more common.

Malpresentation

Although malpresentations can occur more frequently than with singleton births, in about half of twin pregnancies both babies are cephalic presentations and in three-quarters of cases the first baby presents by the vertex.

Cord prolapse

This is a particular risk in cases of premature rupture of the membranes, malpresentation, polyhydramnios and in the interval between the births of the first and second twin.

Prolonged labour

The length of the first stage of labour is usually similar to that of a singleton birth. However, because of the overdistension of the uterus and abdominal muscles, there may be uterine inertia in some mothers.

Monoamniotic twins

As monoamniotic twins share the same sac, there is the risk of cord entanglement. Delivery is recommended around 32–34 weeks’ gestation and by caesarean section (Pasquini et al 2006).

Deferred delivery of the second twin

In the last few years there have been cases reported where the first twin has been born, often very prematurely, and then labour has stopped. Labour in some instances has not recommenced again for a period of time; pregnancies have been recorded with a gap of 30 days or more. This can be beneficial to the second twin, as betamethasone can be administered to help mature the lungs. Throughout this period, the mother will need an enormous amount of support from midwives. She will be concerned about the twin who has been born as well as still being pregnant and concerned for that baby. She will need close monitoring for signs of infection.

Onset of labour

The average gestational duration of multiple pregnancies with two, three and four babies are as follows:

Approximately 30% of twins and 80–95% of triplets are born spontaneously before 37 weeks (Clarke & Roman 1994). If labour does begin prematurely when the chances of survival are not good, the mother may be given drugs to inhibit uterine activity. Intravenous salbutamol and sulindac tablets are the drugs most commonly used. The cause of the premature labour must be determined quickly, so that it can be treated if possible; for example, a urinary tract infection should be treated with antibiotics. Most twin pregnancies are induced by 38 weeks.

Care in labour

When a mother expecting a multiple birth is admitted in labour, the team who will be present at the delivery should be informed. As well as midwives and obstetric medical staff, an anaesthetist and paediatricians should be available (Bryan et al 1997). All those in attendance should be introduced to the parents, and their presence and role explained. If students and other observers are included, the mother’s permission must be sought; ideally this should be prior to labour commencement.

First stage

The first stage of labour is conducted as for a singleton labour, though a multiple pregnancy is considered high risk. Regular monitoring of each baby must be observed – two external transducers can achieve this, or once the membranes are ruptured, a scalp electrode on the presenting twin and the external monitor on the second twin. Uterine activity should also be monitored. Epidural anaesthesia is now the pain relief of choice offered to mothers giving birth to multiples. This form of pain relief has the added advantage that if manoeuvres, such as internal version, forceps delivery, ventouse extraction and emergency caesarean section, are needed, adequate pain relief is in situ. The use of analgesia, such as pethidine, is usually avoided as this may cause respiratory depression, particularly in the case of the second baby, who may already be experiencing reduced oxygen levels (Bryan et al 1997). It is widely accepted that the risk to the second-born infant is significantly higher (MacGillivray & Campbell 1988). Thompson et al (1983), in a Scottish study, report a death rate for first twins of 47.6 per 1000 compared with 64.6 for second twins.

If there are any signs of fetal distress at any time during the first stage of labour to either baby, then an emergency caesarean section must be performed.

Second stage

The obstetrician, anaesthetist and paediatrician should be present together with the midwife because of the risk of complications. Continuous monitoring of contractions and both infants’ heartbeats should be in progress.

The delivery room should be suitable for an emergency caesarean section or in close proximity to an operating theatre. Two sets of resuscitation equipment and incubators should be prepared. The delivery trolley should include the requirements for episiotomy, amniotomy, instrumental delivery and extra cord clamps. Equipment for local and general anaesthesia should be available if epidural anaesthetic is not already established and effective.

The second stage is conducted as usual for the birth of the first baby. When the labour is preterm, forceps may be used to protect the infant’s head during delivery. The cord should be firmly clamped in two places and cut between the clamps. Extra cord clamps may be needed if blood gases have to be taken; local unit policy should be followed for this. If the maternal side is not secure, the second baby, in the case of monochorionic twins, may suffer exsanguination. When the first twin is born, the time of delivery must be noted. The first infant and the cord should be clearly labelled ‘Twin 1’ or with the parents’ chosen name, if known. The baby should be shown to the mother if the condition is satisfactory, or the parents constantly informed of progress if resuscitation is required. When the condition is satisfactory, the suckling of the baby breastfeeding will stimulate uterine activity.

The lie, presentation and position of the second baby must be ascertained by abdominal palpation and confirmed by vaginal examination. If transverse or oblique, this must be corrected by external version to longitudinal. If this is not possible, an emergency caesarean section is performed. The fetal heart rate and the mother’s blood pressure and pulse rate must be checked after each procedure.

When it has been confirmed that there is no cord presentation, the second sac of membranes is ruptured and a scalp electrode applied. Once again, a check is made to make sure that the cord has not prolapsed. If contractions do not resume very soon after delivery of the first twin, then a Syntocinon infusion may be needed. The delivery is conducted in the normal way, taking care to note the time and label the baby ‘Twin 2’, and the same for the cord. The interval between the births varies considerably. It has been suggested that 30 minutes should be the maximum time (Barrett 2006). Depending upon gestation and individual circumstances, delayed delivery may be considered, but this is not usual practice.

If more than two babies are expected, the delivery is usually by caesarean section (see below).

Undiagnosed twins

It is unusual nowadays for a multiple pregnancy to remain undiagnosed at the time of delivery. However, where ultrasonography is not available or not used routinely for all expectant mothers, or in the case of an unbooked woman, this can still occur. In this situation, ergometrine or Syntometrine should not be administered until after the birth of the baby, so there is no risk to a possible twin of severe anoxia, which may lead to death, or precipitate delivery of a possibly brain-damaged infant. Rupture of the uterus is also a risk. If drugs have been administered, the second baby requires immediate delivery. A general anaesthetic may be required and a muscle relaxant given. Caesarean section may be indicated.

It should be appreciated that both parents in this situation are likely to be in a state of shock (Theroux 1989). Suddenly there are two babies to whom they must relate. They may already have formed a bond with the first infant and find it difficult to accept the unexpected baby (Bryan et al 1997). Midwives, if aware of the possible problem, can give extra support to allow expression of negative feelings and help acceptance of the new situation.

Third stage

Management may vary in different hospitals. It is usual to give an injection of ergometrine maleate 250–500 mcg intravenously or Syntometrine 1 ml intramuscularly with the birth of the anterior shoulder of the last baby. When the uterus is felt to contract, controlled cord traction is applied to both/all cords at the same time.

Following delivery, there is an increased risk of haemorrhage from the large placental site and overdistended uterine muscles, which may also contribute, as the abdominal muscles are more relaxed.

Examination of placenta and membranes

The midwife must make the usual examination to ensure completeness and detect any deviation from normal. If the babies are of different sex, then they must be dizygotic twins, with either two separate placentas or one that has fused together, but each will have its own set of membranes, that is, amnion and chorion. When the babies are of the same sex, they may be monozygotic or dizygotic. It used to be thought that there was only a single chorion in the case of all monozygotic twins. However, research has revealed that one-third of monozygotic twins have dichorionic placentas. DNA testing is advisable to confirm zygosity.

Delivery of triplets and higher-order births

The greatest problem for triplet and higher-order births is preterm delivery.

The recommended method of delivery is by caesarean section and in many series of data this rate is greater than 90% for triplets (Lipitz et al 1994). The higher the order, the more likely this becomes (Pons et al 1988).

The delivery of triplets or more is a major event for all staff as well as parents. As much information as possible should be given to the parents about the procedure, and the roles of the many personnel in the delivery room should be explained (Bryan et al 1997). It is crucial that the resuscitation teams are briefed well in advance of the delivery and that each baby has its own paediatric team.

However many infants are involved, the parents should be shown their babies as soon as possible after delivery.

If it is necessary to transfer some or all of the infants to the neonatal unit, photographs should be taken and brought to the mother as soon as possible. Ideally, the babies should be photographed together so that the realities of the multiple birth are established. However, if this is not possible, the pictures should be clearly labelled with the birth order of the babies.

Postnatal care

The immediate postnatal care for a mother who has given birth to twins or more is the same as for a singleton mother, but with special attention to her blood loss and the involution of the uterus. As the babies are likely to be smaller and preterm, it is more difficult for them to maintain their body temperature, so they must be kept warm.

Following delivery, the mother is likely to be very tired. She has probably suffered from a sleep deficit over several months, and a more complicated delivery or caesarean section may compound her exhaustion. The lochia in the first few days is often heavier than after a singleton delivery and the mother is more likely to complain of afterpains.

In addition, the mother has two or more babies for whom she must care and relate. Her anxieties may be increased if her babies are preterm. One, both, or, in the case of triplets or more, all, may be nursed in the neonatal unit. The mother will need additional support and help if she has one baby on the postnatal ward with her and one in the NICU. She may feel more inclined to stay with the healthy baby on the ward rather than the one in NICU, though if the long-term outcome is uncertain she should be encouraged to spend as much time as possible with the sick baby.

Some units have established transitional care wards where small, well babies can remain with their mothers with the aid of specially trained midwives or nurses who are available to support, assist and advise them on the care and specialized feeding the babies need.

Sadly, it is not uncommon for very sick babies to be transferred, sometimes without their mother, from the delivery hospital to a regional referral unit where intensive neonatal nursing care can be offered. The distances involved can be great and extremely costly to the parents and the neonatal services (Papiernik 1991). This situation is traumatic for all the family. Midwifery staff must strive to reunite the family as soon as the condition of the babies allows. Regular communication during the separation is vital. The splitting up of the family group is often avoided if the babies are transferred to the regional referral unit in utero. Bowman et al (1988) demonstrated that such babies had a better prognosis than those who needed to be transferred after birth.

Feeding multiples

During the first few weeks, the mother is going to need a lot of extra support and advice to help her establish breastfeeding. She should allow 4–6 weeks to get into a routine and achieve this. Twins can breastfeed separately or together; if fed together, the feeds will only take a little longer than with a single baby. The mother will have more quality time with her babies, as she has no bottles to sterilize or feeds to make up (see Ch. 43).

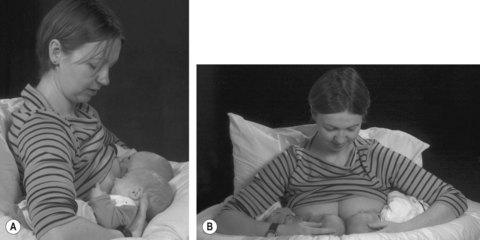

Whilst in hospital, help should be available at every feed until the mother feels confident. It is advisable in the first few days for her to feed her babies separately; this gives her a chance to get to know each baby as an individual and to feel confident handling and putting the baby to the breast. It can be overwhelming for the mother with a first baby to try to perfect feeding two babies together right from the start. Once breastfeeding is established, some mothers prefer to feed both infants together, thus saving time; others prefer to feed separately but wake the second to feed immediately after the first so the routine is maintained. There is no one right way (Davies & Denton 1999); it has to be the mother’s preference and what fits in with her family, developing the mother’s confidence and ability to cope. One of the main causes of nipple soreness and backache is incorrect positioning of both babies at the breast and the mother’s sitting position whilst feeding. It is very important for mothers to be taught right from the start to use plenty of pillows to support their backs and also to take the weight of the babies for feeding. The pillows should bring the babies up to nipple level so the mother can sit with her back straight and not lean forwards over the babies. As the weight of the babies is taken by the pillows, the mother’s hands are free to reposition a baby should either of them come off the breast and to lift one baby up for winding purposes. There are a variety of positions in which the mother can hold her babies for feeding. The most usual one for newborns is the underarm hold (Fig. 59.5).

Some mothers will choose to wholly or partially bottle feed their babies. Partners, family and friends are then able to share in feeding routines.

Whatever the mother’s choice of feeding method, the midwife should support her in that choice.

Coming home

If the babies have been born preterm, the mother may go home several days or weeks before her babies. It is unusual for babies to be discharged home at different times, but there are occasions when this happens. This will put added strain on the parents, who have to care for one baby at home whilst finding time to visit the sick one in hospital. Criticism of parents who do not visit frequently should be avoided. It may be necessary to arrange for a room on the NICU for the mother to room-in so she gains confidence in caring for the babies before discharge. This transition will be smoother if the mother has adequate help at home for the first few weeks after discharge.

Sources of help

There is no statutory help routinely available for mothers of twins, triplets or more in the UK. If there are concerns about the family circumstances and the parents’ ability to cope, then social services should be contacted before the babies are born. Further Education Colleges running the Diploma in Child Care and Education often welcome the opportunity to place their students with families for work experience. Home Start is another organization which may be able to assist (see website). Local Sure Start centres may have details of other help available.

Family relationships

A mother may find it more difficult to relate to both/all of her babies at the beginning. This is very common and she should be reassured that these feelings will pass and she will bond with all her babies.

A strong preference may develop for one of the babies in the early days. Research has shown that this is usually for the baby who was heavier at birth (Spillman 1984). The mother should be reassured that this is normal and in time her relationship with the other baby or babies will improve.

Becoming overtired and feeling overwhelmed with the immensity of their task is also a risk for both parents. There may also be problems with other children in the family, especially toddlers. It is hard enough for a 2-year-old child to accept one new baby. When two or more arrive simultaneously, there may be real difficulties. Single older children may see their parents as a pair and the twins as a pair and themselves on their own, so it is helpful for the parents to arrange for a special friend to spend time with the older child. It is usual for the new babies to give a present to their older sibling; it is a good idea for the older child to choose a small different gift for each twin. Cuddly toys are a good idea. Being the first gifts the twins receive can make the sibling feel very special.

Individuality and identity

Most parents of twins appreciate the importance of their children developing their own identities. This, ideally, should be discussed in the antenatal period. Parents of twins are encouraged to treat their children as individuals, giving them the same opportunities as a single-born child. Ways in which they can emphasize their individuality should be discussed in parent education classes. These include choosing names that do not sound the same or rhyme and commence with a different first letter, and dressing the children in different-coloured clothes (Bryan & Hallett 2001).

Postnatal depression

In view of all the possible complications, increased risk of surgical intervention and the other stresses involved in having a multiple birth, it is perhaps not surprising that there is an increased risk of depression (Spillman 1993, Thorpe et al 1991).

The health professionals caring for the mother should recognize the signs that depression is developing. It is helpful if there is continuity of care by a known midwife and a health visitor who has been introduced to the family before the babies are born. If the babies are still in hospital, it is still important for the mother to receive visits from her midwife and health visitor at home.

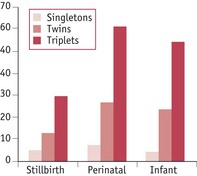

Bereavement

Mortality rates for multiple births have long been established as significantly higher than those of singletons, with twins about 5 times, and triplets about 10 times, more likely to die within the first year of life (MacFarlane & Mugford 2000) (Fig. 59.6).

Figure 59.6 Mortality in multiple births, England and Wales, 2005, per 1000 births

(Source: ONS London.)

The higher incidence of preterm delivery and the associated complications are the main reason for the increased death rates. The loss of all the babies in a multiple pregnancy is tragic and the grief of the parents is usually fully recognized, but the situation is more complex when one twin or triplet dies. Parents then have to cope with grieving for the dead baby (or babies if two triplets die) at the same time as caring for the survivor. Professionals, as well as family and friends, can fail to realize that the grief is just as great when one baby dies, and the joy of having a healthy child will not diminish the depth of the emotions or compensate for the loss. Parents may be regarded as ungrateful for the survivor, particularly if one twin dies during pregnancy or delivery or shortly after birth. They may need help to fully acknowledge their feelings and should be given information and support and offered counselling, which should be ongoing, as soon as the death is confirmed. The loss of status of being parents of twins, triplets or more must not be underestimated. They will continue to be parents of however many children are born and this should always be acknowledged (Bryan 1986).

Encouragement should be given to the parents to talk about the confusing, contradictory feelings they may have and to think and talk about their dead baby, as this will allow the mourning process to take place (Lewis 1979, Lewis & Bryan 1988).

If the babies are dichorionic, same-sex twins (triplets), the parents should be given the option for DNA testing so they will know the zygosity of their babies.

Each case must be treated individually, and the information and care required will vary in some ways, depending upon when the baby died. The different situations and recommendations for the care of these families is given in detail in the section on bereavement in the Multiple Births Foundation Guidelines for professionals (Bryan & Hallett 1997).

Disability

The risk of disability is greater with multiple births. The chance of a triplet pregnancy resulting in a baby with cerebral palsy is 47 times greater, and for a twin pregnancy 8 times greater, than that of a singleton pregnancy (Petterson et al 1990). Caring for one child with a disability and another who is healthy brings many challenges, especially with twins. Often, the healthy child has just as many problems and may imagine that he or she caused the problem or resent the attention paid to the other child. Many potential emotional and behavioural problems may be avoided if the family are supported and advised appropriately as early as possible.

Multifetal pregnancy reduction

Multifetal pregnancy reduction may be offered to parents who conceive triplets or more on the basis that reduction to two or even one fetus provides a better chance of the healthy survival of each baby. The procedure is usually carried out between the 10th and 12th weeks of pregnancy; the most common method is to inject potassium chloride into the fetal thorax. When parents are presented with this immensely difficult decision, they must be provided with information about the risks and consequences of the procedure and offered counselling so that they consider the implications fully before making a final choice (see Ch. 28).

Selective feticide

If one of the babies in a multiple pregnancy has a serious abnormality, the same clinical procedure as described for multifetal pregnancy reduction may be used. Again, the parents will need very detailed information about the risks and counselling before making their final decision. As the dead baby will remain in the uterus until the delivery, the midwife has an important role to play in acknowledging the bereavement and supporting the mother through this very emotional time before and after the birth.

Planning ahead

It is important that good family planning advice is offered to the parents following a multiple birth. Genetic counselling may be needed for those who have lost a baby. Follow-up of survivors should be arranged, especially when the infants are monozygous or have experienced neonatal complications.

Key Points

Baldwin VJ. Pathology of multiple pregnancy. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1994.

Barrett JFR. Management of labour in multiple pregnancies. In: Kilby M, Baker P, Critchley H, et al, editors. Multiple pregnancy. London: RCOG; 2006:223-233.

Botting B, Macfarlane AJ, Price FV. Three, four & more: a study of triplets and higher order births. London: HMSO; 1990.

Bowman E, Doyle LW, Murton LJ, et al. Increased mortality of preterm infants transferred between tertiary perinatal centres. British Medical Journal. 1988;297(6656):1098-1100.

Bryan EM. The death of a newborn twin. How can support for the parents be improved? Acta Geneticae Medicae et Gemellologiae. 1986;35(1–2):115-118.

Bryan EM, Hallett F. Guidelines for professionals: bereavement. London: The Multiple Births Foundation; 1997.

Bryan EM, Hallett F. Guidelines for professionals: twins and triplets: the first five years and beyond. London: The Multiple Births Foundation; 2001.

Bryan EM, Denton J, Hallett F. Guidelines for professionals: multiple pregnancy. London: The Multiple Births Foundation; 1997.

Carlin A, Neilson JP. Twin clinics: a model for antenatal care in multiple gestations. In: Kilby M, Baker P, Critchley H, et al, editors. Multiple pregnancy. London: RCOG; 2006:121-137.

Clarke JP, Roman JD. A review of 19 sets of triplets. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1994;134(1):50-53.

Chitayat D, Hall J. Genetic aspects of twinning. In: Kilby M, Baker P, Critchley H, et al, editors. Multiple pregnancy. London: RCOG; 2006:89-94.

Collins J, Graves G. The economic consequences of multiple gestation pregnancy in assisted conception cycles. Human Fertility. 2000;3(4):275-283.

Davies ME. Managing multiple births, supporting parents. Modern Midwife. 1995;5(11):10-14.

Davies ME, Denton J. Feeding twins, triplets and more. London: The Multiple Births Foundation; 1999.

Denton J, Bryan EM. Prenatal preparation for parenting twins, triplets or more: the social aspect. In: Whittle M, Ward RH, editors. Multiple pregnancy. London: RCOG; 1995:119-128.

Derom R, Derom C, Vlietnick R. The risk of monozygotic twinning. In: Blickstein I, Keith LG, editors. Iatrogenic multiple pregnancy, clinical implications. New York: Parthenon; 2001:9-19.

Fisk NM. The scientific basis of feto-fetal transfusion syndrome and its treatment. In: Humphrey WR, Whittle M, editors. Multiple pregnancy. London: RCOG; 1995:235-250.

Fisk NM, Bryan EM. Routine prenatal determination of chorionicity in multiple gestation: a plea to the obstetrician. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1993;100(11):975-977.

Fuducia A. Breastfeeding three babies at once. Twins, Triplets and More. 1995;6(3):10-11.

Khunda S. Locked twins. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1972;39(3):453-459.

Kurinczuk J. Epidemiology of multiple pregnancy: changing effects of assisted conception. In: Kilby M, Baker P, Critchley H, et al, editors. Multiple pregnancy. London: RCOG; 2006:121-137.

Landy HJ, Nies BM. The vanishing twin. In: Keith L, Papiernik E, Keith D, et al, editors. Multiple pregnancy, epidemiology, gestation, and perinatal outcome. New York: Parthenon; 1995:59.

Lewis E. Mourning by the family after a still birth or neonatal death. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1979;54(4):303-306.

Lewis E, Bryan EM. Management of perinatal loss of a twin. British Medical Journal. 1988;297(6659):1321-1323.

Lipitz S, Reichman B, Uval J. A prospective comparison of the outcome of triplet pregnancies managed expectantly or by multifetal reduction to twins. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1994;170(3):874-879.

MacFarlane AJ, Mugford M. Birth counts: statistics of pregnancy and childbirth. Norwich: The Stationery Office; 2000.

MacGillivray I, Campbell DM. Management of twin pregnancies. In: MacGillivray I, Campbell DM, Thompson B, editors. Twinning and twins. Chichester: John Wiley; 1988:111-139.

Moore TR, Gale S, Benirschke K. Perinatal outcome of forty nine pregnancies complicated by acardiac twinning. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1990;163(3):907-912.

Papiernik E. Costs of multiple pregnancies. In: Harvey D, Bryan EM, editors. The stress of multiple births. London: The Multiple Births Foundation; 1991:22-34.

Pasquini L, Wimalasundera RC, Fichera A, et al. High perinatal survival in monoamniotic twins by prophylactic sulindac, intensive ultrasound surveillance, and Cesarean delivery at 32 weeks. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2006;28(5):681-687.

Perlman EJ, Stetton G, Tuckmuller CM, et al. Sexual discordance in monozygotic twins. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1990;37(4):551-557.

Petterson B, Stanley F, Henderson D. Cerebral palsy in multiple births in Western Australia. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1990;37(3):346-351.

Pons JC, Mayenga JM, Plu G, et al. Management of triplet pregnancy. Acta Geneticae Medicae et Gemellologiae. 1988;37(1):99-103.

Salha O, Sharma V, Dada T, et al. The influence of donated gametes on the incidence of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Human Reproduction. 1999;14(9):2268-2273.

Spillman JR. The role of birthweight in maternal–twin relationships. MSc Thesis, Cranfield: Cranfield Institute of Technology; 1984.

Spillman JR. Expecting a multiple birth: some emotional aspects. British Journal for Nurses in Child Health. 1986;1(10):298-299.

Spillman JR. Perinatal loss in multiple pregnancy. Proceedings: 23rd International Congress of Midwives, 1993, 1776-1785.

Steinberg LH, Hurley VA, Desmedt E, et al. Acute polyhydramnios in twin pregnancies. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1990;30(3):196-200.

Theroux R. Multiple birth: a unique parenting experience. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing. 1989;3(1):35-45.

Thompson B, Pritchard C, Corney G: Perinatal mortality in twins by zygosity and placentation. Paper given at the 4th Congress of International Society of Twin Studies, London, 1983.

Thorpe K, Golding J, Macgillivray I, et al. Comparison of prevalence of depression in mothers of twins and mothers of singletons. British Medical Journal. 1991;302(6781):875-878.