Chapter 63 Rhythmic variations of labour

Introduction

This chapter looks at prolonged labour and explores the issues that surround altered uterine action; prevention, diagnosis, management and associated problems. To maximize learning, it is anticipated that the reader has a working knowledge of the underlying physiology, care and management of normal labour (Chs 35–37).

In normal labour, the uterine contractions become progressively longer, stronger, and increase in frequency, causing the complete effacement and progressive dilatation of the os uteri in the first stage, steady delivery of the baby in the second stage, and expulsion of the placenta and membranes and the control of haemorrhage to complete the third stage of labour (Ch. 35).

Altered uterine action can occur at any stage of labour and is often attributed to an abnormal pattern of uterine contractility, resulting in slow or rapid progress. Vigilant observation and assessment of a woman in labour is therefore paramount in the prevention, detection and diagnosis of altered uterine action. Unfortunately, there is no way to predict the kind of labour progression (in terms of dilatation and descent) that a given contractile pattern will produce – that is, the quality of contractions can give little information about the course of labour. In this context, the value of antenatal education in preparing the woman and her partner for labour and the possibility of a non-perfect labour is important. Since abnormal uterine action may be inefficient or over-efficient, a useful tool to assess the progress of labour is the partogram.

The partogram

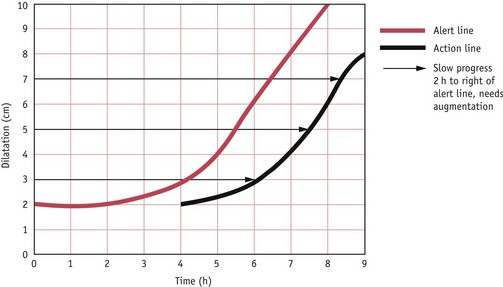

The partogram is an observation chart that may be used to facilitate assessment of the progress of labour, including maternal and fetal wellbeing (Ch. 37). Historically, progress is measured by linear progression along a prescribed time scale, whereby a curve of cervical dilatation is measured in centimetres plotted against time in hours (Friedman 1955), and descent of the head abdominally. Over the years, modifications to the partogram have occurred, resulting in the introduction of alert and action lines. Originally, the action line was 2 hours to the right of the alert line, and augmentation instituted at this time (Fig. 63.1). Once labour is confirmed as in the active phase, cervical dilatation is expected to progress at <2 cm dilatation in 4 hours (NICE 2008). Albers (2007) supports this as a realistic expectation; she goes on to say that for some women, progress may be as little as 0.3 cm per hour. Clearly this demonstrates that partograms are only a tool and the progress of labour should not be assessed upon cervical effacement and dilation alone, without the assessment of the descent of the presenting part abdominally. Behaviour is shown to be a key part in normal progression alongside one-to-one care by a midwife.

Figure 63.1 Normogram/partogram of the cervimetric progress commencing at 2 cm dilatation. ‘Alert’ line outlines normal progress. ‘Action’ line indicates when augmentation should be instituted.

(After Studd 1973)

To maximize use, NICE (2008) recommends that, if a partogram is used, it should record all of the following observations:

Further research and education is warranted to review the current mindset of women, midwives and obstetricians.

Reflective activity 63.1

Review your local trust partogram or labour assessment chart in relation to the NICE guidelines for intrapartum care (NICE 2008).

What supportive evidence is acknowledged to justify its use?

Prolonged labour

Prolonged labour is described as a clinical presentation of labour which has exceeded the expected time limits. This is owing to an alteration in uterine contractility that is considered to interfere with the normal progress of labour. Furthermore, it is viewed as a deviation in normal progress of labour indicated by cervical dilatation or in the descent of the presenting part.

The term ‘prolonged labour’ is difficult to define, since it is dependent upon the actual time at which labour is presumed to have begun; therefore, accurate history is essential. Enkin et al (2000) suggest that the most frequently used marker for the onset of labour for women choosing a hospital birth is the time of admission. Since this is an arbitrary measurement, it can lead to an inaccurate diagnosis of the onset of labour. The presumed failure of the cervix to dilate within a given time limit based on the inaccurate diagnosis of labour, may result in the use of inappropriate intervention, preventing the woman from following her own labour pattern.

The majority of women whose labours are prolonged are primigravidae, with inefficient uterine action being the most common cause (El-Hamamy & Arulkumaran 2005). The birth of the first child alters the birth canal and subsequent deliveries are usually easier, since the mother has the potential benefits of experience and belief in herself.

Causes of prolonged labour

Any one of these factors, or a combination of them, may cause prolonged labour, which remains a major cause of maternal death and infant morbidity in developing countries (Berhane & Hogberg 1999).

The provision of appropriate midwifery care is crucial to the early diagnosis of underlying problems, which, if undetected, may create potential hazards to the mother and fetus. Midwifery care should be focused on the following areas:

Dangers to the mother

Dangers to the fetus

Prolonged labour is associated with fetal acidosis and intrauterine hypoxia, which can result in meconium aspiration and may lead to perinatal dealth (MCHRC 2000).

Overview of midwifery management

If the principles in management of labour care are followed, it should alert the midwife to the development of a prolonged labour and, therefore, the subsequent action necessary. The following points are particularly relevant:

Principles of the active management of labour

The principles of the active management of labour centre on actions taken to promote the continuance of regular effective contractions resulting in a shorter labour. Since O’Driscoll implemented this approach in 1968 (O’Driscoll et al 2003), the policy of active management has been modified along the years to accommodate opposition to the management.

The focus should be placed on the following:

Active management of labour is not normally applied to women in labour with twins or malpresentations. Augmentation should be used with extreme caution in multigravidae and women with uterine scars, because of the risk of uterine rupture (Lewis 2007). To appreciate the implications of active management, an understanding of amniotomy and use of oxytocin is required.

Amniotomy

Amniotomy is a procedure in which the amniotic membranes are ruptured. Whilst amniotomy has been used as a means of accelerating labour in normal labour, a recently published Cochrane review of 14 studies calls into question the use of amniotomy for this purpose. Smyth et al (2007) conclude that the current evidence does not support the use of routine amniotomy in normally progressing labours or in labours which have become prolonged.

The underlying physiology that instigates contractions is the increase in prostaglandin release and the pressure from the fetal head upon the cervix, which is associated with the increase in pain and the use of epidural anaesthesia (Smyth et al 2007). The benefits of intact membranes are the maintenance of an even hydrostatic pressure to the whole fetal surface during labour and a reduced likelihood of infection. Fetal hypoxia is therefore less likely because retraction of the placental site, and thus impairment of the uteroplacental circulation, will not occur. Accurate assessment of established labour and justification of amniotomy must be carefully addressed. The woman needs to retain control and make informed choices even when deviation from normal progress occurs (DH 2007).

Augmentation with oxytocin

If augmentation with oxytocin is required, vigilant midwifery care is essential. The use of oxytocin in the active management of labour varies. Although it is rare for a primigravid uterus to rupture, in a multigravida, oxytocin should be used with extreme caution after obstructed labour has been excluded. In these situations, a multidisciplinary approach to care is required.

Use of oxytocin

Management of a prolonged second stage of labour

It is important to consider that prolonged labour can occur at any stage and the progress of the first stage may influence the management of the second and third stages. Historically, time limits have been imposed on the length of the second stage; however, it is now considered good practice to assess each woman on an individual basis, ensuring that maternal and fetal observations remain within normal limits.

The main causes of delay in the second stage of labour are inefficient uterine action, maternal obesity, full bladder or rectum, a rigid perineum, and, rarely, a contracted pelvic outlet.

Fetal causes include a persistent occipitoposterior position, deep transverse arrest, malpresentations, fetal macrosomia and fetal abnormality, such as hydrocephaly.

If progress is slow and the woman is able to and wishes to adopt an upright position, the midwife should support this, as it is believed that the direct pressure of the presenting part against the posterior wall of the vagina stimulates the release of oxytocin (Ferguson’s reflex; see Chs 35 and 37) and thereby enhances the urge to bear down. As in the first stage of labour, meticulous observations continue during the second stage. The obstetrician must be informed if there appears to be lack of progress or if fetal or maternal distress develops.

Midwifery management of the third stage of labour following a prolonged first and/or second stage

Invariably, if the first and second stages of labour have progressed normally, the third stage will too. However, the midwife must remain observant. If problems have occurred during the labour, active management will be the method of choice because of the associated risks. Women at greater risk of complications of prolonged third stage are those who have had inadequate contractions or have developed a constriction ring, a full bladder or morbidly adhered placenta.

In addition to active management of the third stage of labour with oxytocic drugs, the midwife should be vigilant, avoid ‘fiddling’ with the uterus and ensure that the bladder is empty. Alternative strategies may be used, which include the encouragement of skin-to-skin contact between mother and infant (Ashmore 2001), change of maternal position, and breastfeeding, which may stimulate the uterus to contract by the release of oxytocin. In some instances, oxytocin may have to be administered intravenously by infusion, if contractions are inadequate or absent or the above management has failed.

The psychological aspects of prolonged labour

The psychological needs of women who undergo a prolonged or augmented labour focus on the level of pain experienced resulting from increased intervention and the knowledge of an associated risk of an emergency caesarean section or instrumental delivery. In a recent study where women reported a negative birth experience following a prolonged labour, feelings of immense pain and deep negative emotions during labour were common (Nystedt et al 2005). Inadequate pain relief made women feel more anxious, out of control, and fearful. These feelings are associated with the risk of developing trauma symptoms following delivery. Women who negatively appraise their birth experience may be at risk of a difficult postnatal recovery, in which their transition to motherhood and their interaction with their babies may be interrupted (Fenwick et al 2003) (Ch. 69). In situations where women encounter a negative birth experience with their first child, Gottvall & Waldenstrom (2002), suggest that they are more likely to delay a second pregnancy and have fewer subsequent children.

Good communication is essential to allay unnecessary anxiety and to enable women and their partners to understand what is happening, to feel involved in all discussions and make decisions regarding their care. Maintaining control during a long and protracted labour can be facilitated by good midwifery support, in which the need for pain relief is regularly assessed with options discussed. After delivery, discussion between the woman and the midwife who cared for her in labour should take place at a suitable time. This can help the woman to come to terms with the events of her labour and raise her self-esteem.

Reflective activity 63.3

To complete this activity, you will need access to your local database.

What is the normal delivery rate in your unit?

How long is the average length of labour for primigravid and multigravid women?

How many women had their labours augmented with: (a) amniotomy; (b) amniotomy with intravenous oxytocin?

Of these, how many women had: (a) normal deliveries; (b) instrumental deliveries; (c) caesarean section?

Over-efficient uterine action (precipitate labour)

Labour is sometimes very rapid with intense frequent contractions, and delivery occurs within an hour (Stables 2010). This is more common in the multiparous woman and is usually caused by a minimal resistance of the maternal soft tissues. The first stage of labour may occur almost without pain and only when the head is about to be born does the woman become aware of it. The mother may sustain lacerations of the cervix and perineum and is at risk of postpartum haemorrhage. Fetal complications include hypoxia as a result of intense frequent contractions, and intracranial haemorrhage may occur as a result of rapid descent through the birth canal. Other dangers include injuries sustained as a result of being delivered in an unsuitable place or falling to the ground. If the woman has a history of precipitate births, it is advisable for her to have a delivery pack at home and for local midwives to be made aware of her history and address.

Tonic uterine action

Definition

This is a rare condition in which the uterus increases powerful contractions to overcome an obstruction; eventually, one long contraction is maintained. It is synonymous with severe acute pain accompanied by rapid deterioration in maternal condition and intrauterine death due to cessation of oxygen delivery to the fetus.

Midwifery management

The midwife’s role is to administer oxygen while summoning emergency medical and midwifery aid to resuscitate the mother, as immediate delivery is required to prevent a ruptured uterus. The management is usually by caesarean section. Caution must be taken not to confuse tonic uterine action with tetanic uterine action, which occurs as a result of uterine hyperstimulation, caused usually by injudicious use of oxytocics. If oxytocin is being administered intravenously, the infusion should be stopped. Encourage the woman to adopt the left lateral position to enhance uteroplacental blood flow, and inform the obstetrician.

Cervical dystocia

This is when the uterus contracts normally but the cervix fails to dilate. Its occurrence is rare but diagnosis is important to prevent maternal and fetal distress. The cervix might efface but fails to dilate; the woman may have a history of cervical surgery or congenital abnormality of the cervix. It is important that this condition is excluded prior to the use of oxytocin, because of the associated risk of uterine rupture. Vaginal delivery is therefore impossible and a caesarean section is performed.

Summary

Good midwifery care, including the accurate diagnosis of established labour, prevention of maternal dehydration, and good communication skills, may prevent the development of prolonged labour. However, if prolonged labour occurs, the midwife needs to remember the importance of vigilance and accurate record-keeping. Working in partnership with the woman and liaising with relevant healthcare professionals is essential.

Sensitive and empathetic midwifery care is also required to support women experiencing precipitate delivery, and in the careful planning of future births. In either situation, the midwife should recognize the potential need for an opportunity for the woman to discuss her labour experiences.

Key Points

Albers L. The evidence for physiologic management of the active phase of the first stage of labor. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2007;52(3):207-215.

Ashmore S. Implementing skin to skin contact in the immediate postnatal period. MIDIRS Midwifery Digest. 2001;11(2):247-250.

Berhane Y, Hogberg U. Prolonged labour in rural Ethiopia: a community based study. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 1999;3(2):33-39.

Champion P, McCormick C. Putting the evidence into practice. In: Champion P, McCormick C, editors. Eating and drinking in labour. Oxford: Books For Midwives; 2002:124-136.

Cluett ER, Pickering R, Getliffe K, et al. Randomised controlled trial of labouring in water compared with standard of augmentation for management of dystocia in first stage of labour. British Medical Journal. 2004;328(314):1-6.

Department of Health (DH). Maternity matters: choice, access and continuity of care in a safe service. London: DH; 2007.

El-Hamamy E, Arulkumaran S. Poor progress of labour. Current Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2005;15(1):1-8.

Enkin M, Keirse MJNC, Neilson J, et al. Prolonged labour. In: A guide to effective care in pregnancy and childbirth. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000:332-340.

Fenwick J, Gamble J, Mawson J. Women’s experiences of Caesarean section and vaginal birth after Caesarean: a Birthrites initiative. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2003;9(1):10-17.

Friedman EA. Primigravid labor – a graphicostatistical analysis. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1955;6:567-589.

Gottvall K, Waldenstrom U. Does a traumatic birth experience have an impact on future reproduction? British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2002;109(3):254-260.

Haddad PF, Morris NF, Spielberger CD. Anxiety in pregnancy and its relation to use of oxytocin and analgesia in labour. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1985;6(2):77-81.

. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and ChildHealth (CEMACH). Saving mothers’ lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer – 2003–2005. The Seventh Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. Lewis, G. London: CEMACH, 2007.

Maternal and Child Health Research Consortium (MCHRC). Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirths and Deaths in Infancy: 7th Annual Report. London: MCHRC; 2000.

Micklewright A, Champion P. Labouring over food: the dietician’s view. In: Champion P, McCormick C, editors. Eating and drinking in labour. Oxford: Books For Midwives; 2002:29-45.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Intrapartum care: care of healthy women and their babies during childbirth, CG 55. London: NICE; 2008.

Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC). Midwives rules and standards. London: NMC; 2004.

Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC). The code. Standards of conduct, performance and ethics for nurses and midwives. London: NMC; 2008.

Nystedt A, Hogberg U, Lundman B. The negative birth experience of prolonged labour: a case-referent study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2005;14(5):579-586.

O’Driscoll K, Meagher D, Robson M. Active management of labour, ed 4. London: Mosby; 2003.

Ramsey JE, Greer I, Sattar N. Obesity and reproduction. British Medical Journal. 2006;333(7579):1159-1162.

Smyth RMD, Alldred SK, Markham C: Amniotomy for shortening spontaneous labour, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD006167, 2007.

Stables D, Rankin J. Abnormalities of uterine action and onset of labour. Physiology in childbearing with anatomy and related biosciences, ed 3. London: Elsevier, 2010.

Studd J. Partograms and normograms of cervical dilatation in management of primigravid labour. British Medical Journal. 1973;4(5890):451-455.