Chapter 7 Recognizing Pneumonia

General Considerations

Pneumonia can be defined as consolidation of lung produced by inflammatory exudate, usually as a result of an infectious agent.

Pneumonia can be defined as consolidation of lung produced by inflammatory exudate, usually as a result of an infectious agent. Other pneumonias demonstrate interstitial disease, and others produce findings in both the airspaces and the interstitium.

Other pneumonias demonstrate interstitial disease, and others produce findings in both the airspaces and the interstitium. Most microorganisms that produce pneumonia are spread to the lungs via the tracheobronchial tree, either through inhalation or aspiration of the organisms.

Most microorganisms that produce pneumonia are spread to the lungs via the tracheobronchial tree, either through inhalation or aspiration of the organisms. In some instances, microorganisms are spread via the bloodstream and in even fewer cases, by direct extension.

In some instances, microorganisms are spread via the bloodstream and in even fewer cases, by direct extension. Because many different microorganisms can produce similar imaging findings in the lungs, it is difficult to identify with certainty the causative organism from the radiographic presentation alone.

Because many different microorganisms can produce similar imaging findings in the lungs, it is difficult to identify with certainty the causative organism from the radiographic presentation alone.

TABLE 7-1 PATTERNS THAT MIGHT SUGGEST A CAUSATIVE ORGANISM

| Pattern of Disease | Likely Causative Organism |

|---|---|

| Upper lobe cavitary pneumonia with spread to the opposite lower lobe | Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) |

| Upper lobe lobar pneumonia with bulging interlobar fissure | Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| Lower lobe cavitary pneumonia | Pseudomonas aeruginosa or anaerobic organisms (Bacteroides) |

| Perihilar interstitial disease or perihilar airspace disease | Pneumocystis carinii (jiroveci) |

| Thin-walled upper lobe cavity | Coccidioides (Coccidiomycosis), TB |

| Airspace disease with effusion | Streptococci, staphylococci, TB |

| Diffuse nodules | Histoplasma, Coccidioides, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (histoplasmosis, coccidiomycosis, TB) |

| Soft-tissue, fingerlike shadows in upper lobes | Aspergillus (allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis) |

| Solitary pulmonary nodule | Cryptococcus (cryptococcosis) |

| Spherical soft-tissue mass in a thin-walled upper lobe cavity | Aspergillus (aspergilloma) |

General Characteristics of Pneumonia

Interstitial pneumonia, on the other hand, may produce prominence of the interstitial markings in the affected part of the lung or may spread to adjacent airways and resemble airspace disease.

Interstitial pneumonia, on the other hand, may produce prominence of the interstitial markings in the affected part of the lung or may spread to adjacent airways and resemble airspace disease. Except for the presence of air bronchograms, airspace pneumonia is usually homogeneous in density (Fig. 7-2).

Except for the presence of air bronchograms, airspace pneumonia is usually homogeneous in density (Fig. 7-2). In some types of pneumonia (i.e., bronchopneumonia), the bronchi, as well as the airspaces, contain inflammatory exudate. This can lead to atelectasis associated with the pneumonia.

In some types of pneumonia (i.e., bronchopneumonia), the bronchi, as well as the airspaces, contain inflammatory exudate. This can lead to atelectasis associated with the pneumonia.

Figure 7-1 Left upper lobe pneumonia.

Several black, branching structures are seen in this upper lobe pneumonia (solid white arrows) that represent typical air bronchograms seen centrally in airspace disease in this patient with pneumococcal pneumonia. The disease is homogeneous in density, except for the presence of the air bronchograms. Because this is airspace disease, its outer edges are poorly marginated and fluffy (dotted white arrow).

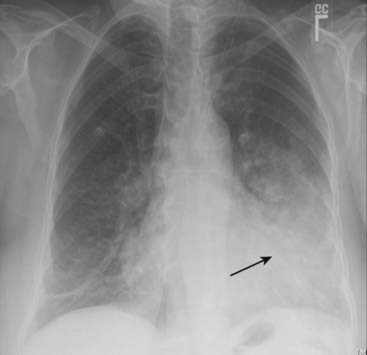

Figure 7-2 Lingular pneumonia.

Airspace disease is present in the lingular segments of the left upper lobe. The disease is of homogeneous density. The disease is in contact with the left lateral border of the heart, which is “silhouetted” by the fluid density of the consolidated upper lobe in contact with the soft tissue density of the heart (solid black arrow).

Box 7-1 Recognizing a Pneumonia—Key Signs

Patterns of Pneumonia

Pneumonias may be distributed in the lung in several patterns described as lobar, segmental, interstitial, round, and cavitary (Table 7-2).

Pneumonias may be distributed in the lung in several patterns described as lobar, segmental, interstitial, round, and cavitary (Table 7-2). Remember, these are terms that simply describe the distribution of the disease in the lungs; they aren’t diagnostic of pneumonia because many other diseases can produce the same patterns of disease distribution in the lung.

Remember, these are terms that simply describe the distribution of the disease in the lungs; they aren’t diagnostic of pneumonia because many other diseases can produce the same patterns of disease distribution in the lung.TABLE 7-2 PATTERNS OF APPEARANCE OF PNEUMONIAS

| Pattern | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Lobar | Homogeneous consolidation of affected lobe with air bronchogram |

| Segmental (bronchopneumonia) | Patchy airspace disease frequently involving several segments simultaneously; no air bronchogram; atelectasis may be associated |

| Interstitial | Reticular interstitial disease usually diffusely spread throughout the lungs early in the disease process; frequently progresses to airspace disease |

| Round | Spherically shaped pneumonia usually seen in the lower lobes of children that may resemble a mass |

| Cavitary | Produced by numerous microorganisms, chief among them being Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

Lobar Pneumonia

The prototypical lobar pneumonia is pneumococcal pneumonia caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae (Fig. 7-3).

The prototypical lobar pneumonia is pneumococcal pneumonia caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae (Fig. 7-3). Although we are calling it lobar pneumonia, the patient may present before the disease involves the entire lobe. In its most classic form, the disease fills most or all of a lobe of the lung.

Although we are calling it lobar pneumonia, the patient may present before the disease involves the entire lobe. In its most classic form, the disease fills most or all of a lobe of the lung. Because lobes are bound by interlobar fissures, one or more of the margins of a lobar pneumonia may be sharply marginated.

Because lobes are bound by interlobar fissures, one or more of the margins of a lobar pneumonia may be sharply marginated. Lobar pneumonias almost always produce a silhouette sign where they come in contact with the heart, aorta, or diaphragm, and they almost always contain air bronchograms if they involve the central portions of the lung.

Lobar pneumonias almost always produce a silhouette sign where they come in contact with the heart, aorta, or diaphragm, and they almost always contain air bronchograms if they involve the central portions of the lung.

Figure 7-3 Right upper lobe pneumococcal pneumonia.

Airspace disease is visible in the right upper lobe and occupies all of that lobe. Because lobes are bounded by interlobar fissures, in this case the minor or horizontal fissure (solid white arrow) produces a sharp margin on the inferior aspect of the pneumonia. Where the disease contacts the ascending aorta (solid black arrow), the border of the aorta is silhouetted by the fluid-density of the pneumonia.

Segmental Pneumonia (Bronchopneumonia)

The prototypical bronchopneumonia is caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Many gram-negative bacteria, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, can produce the same picture.

The prototypical bronchopneumonia is caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Many gram-negative bacteria, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, can produce the same picture. Brochopneumonias are spread centrifugally via the tracheobronchial tree to many foci in the lung at the same time. Therefore they frequently involve several segments of the lung simultaneously.

Brochopneumonias are spread centrifugally via the tracheobronchial tree to many foci in the lung at the same time. Therefore they frequently involve several segments of the lung simultaneously. Because lung segments are not bound by fissures, all of the margins of segmental pneumonias tend to be fluffy and indistinct (Fig. 7-4).

Because lung segments are not bound by fissures, all of the margins of segmental pneumonias tend to be fluffy and indistinct (Fig. 7-4).

Figure 7-4 Staphylococcal bronchopneumonia.

Multiple irregularly marginated patches of airspace disease are present in both lungs (solid white arrows). This is a characteristic distribution and appearance of bronchopneumonia. The disease is spread centrifugally via the tracheobronchial tree to many foci in the lung at the same time so it frequently involves several segments. Because lung segments are not bound by fissures, the margins of segmental pneumonias tend to be fluffy and indistinct. No air bronchograms are present because inflammatory exudate fills the bronchi as well as the airspaces around them.

Interstitial Pneumonia

The prototypes for interstitial pneumonia are viral pneumonia, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with AIDS.

The prototypes for interstitial pneumonia are viral pneumonia, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with AIDS. Interstitial pneumonias tend to involve the airway walls and alveolar septa and may produce, especially early in their course, a fine, reticular pattern in the lungs.

Interstitial pneumonias tend to involve the airway walls and alveolar septa and may produce, especially early in their course, a fine, reticular pattern in the lungs. Most interstitial pneumonias eventually spread to the adjacent alveoli and produce patchy or confluent airspace disease, making the original interstitial nature of the pneumonia impossible to recognize radiographically.

Most interstitial pneumonias eventually spread to the adjacent alveoli and produce patchy or confluent airspace disease, making the original interstitial nature of the pneumonia impossible to recognize radiographically.

![]() Pneumocystis carinii (jiroveci) pneumonia (PCP)

Pneumocystis carinii (jiroveci) pneumonia (PCP)

Figure 7-5 Pneumocystis carinii (jiroveci) pneumonia (PCP).

Diffuse interstitial lung disease is seen, which is primarily reticular in nature. Without the additional history that this patient had acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), this could be mistaken for pulmonary interstitial edema or a chronic, fibrotic process such as sarcoidosis. No pleural effusions are present, as might be expected with pulmonary interstitial edema, and there is no evidence of hilar adenopathy, as might occur in sarcoid.

Round Pneumonia

A round pneumonia could be confused with a tumor mass except that symptoms associated with infection usually accompany the pulmonary findings and tumors are uncommon in children (Fig. 7-6).

A round pneumonia could be confused with a tumor mass except that symptoms associated with infection usually accompany the pulmonary findings and tumors are uncommon in children (Fig. 7-6).

A soft tissue density that has a rounded appearance (solid white arrows) is seen in the right midlung field. The patient is a 10-month-old baby who had a cough and fever. This is a characteristic appearance of a round pneumonia, most common in children and frequently due to either Haemophilus, streptococcal, or pneumococcal infection.

Cavitary Pneumonia

![]() The prototypical organism producing cavitary pneumonia is Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

The prototypical organism producing cavitary pneumonia is Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Primary tuberculosis (primary TB)

Primary tuberculosis (primary TB)

Post-primary tuberculosis (reactivation tuberculosis)

Post-primary tuberculosis (reactivation tuberculosis)

Miliary tuberculosis

Miliary tuberculosis

Figure 7-7 Primary tuberculosis.

There is prominence of the left hilum that is caused by left hilar adenopathy (solid white arrows). Unilateral hilar adenopathy may be the only manifestation of primary infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, especially in children. When it produces pneumonia, primary TB affects the upper lobes slightly more than the lower. It produces airspace disease that may be associated with ipsilateral hilar adenopathy (especially in children) and large, often unilateral, pleural effusions (especially in adults).

Figure 7-8 Post-primary tuberculosis (reactivation tuberculosis).

A cavitary pneumonia is present in both upper lobes (solid white arrows). Numerous lucencies (cavities) are seen throughout the airspace disease in the right upper lobe (solid black arrows). A cavitary upper lobe pneumonia is presumptively TB, until proven otherwise. In addition, airspace disease is seen in the lingula (dashed white arrow), another finding suggestive of TB, a disease which can spread via a transbronchial route to the opposite lower lobe or another lobe in the lung.

Figure 7-9 Miliary tuberculosis.

Innumerable small round nodules are present in this close-up of the left lung in a patient with miliary tuberculosis (black circle). At the start of the disease, the nodules are so small they are frequently difficult to detect on conventional radiographs. When they reach about 1 mm or more in size, they begin to become visible. Miliary tuberculosis will clear relatively rapidly with appropriate treatment and does not heal with calcification.

Aspiration

There are many causes of aspiration of foreign material into the tracheobronchial tree, among them neurologic disorders (stroke, traumatic brain injury), altered mental status (anesthesia, drug overdose), gastroesophageal reflux, and postoperative changes from head and neck surgery.

There are many causes of aspiration of foreign material into the tracheobronchial tree, among them neurologic disorders (stroke, traumatic brain injury), altered mental status (anesthesia, drug overdose), gastroesophageal reflux, and postoperative changes from head and neck surgery. Aspiration almost always occurs in the most dependent portions of the lung.

Aspiration almost always occurs in the most dependent portions of the lung.

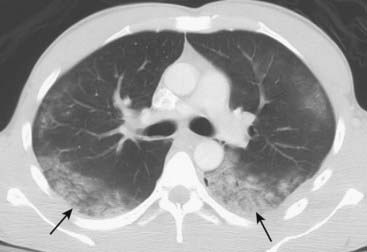

Figure 7-10 Aspiration, both lower lobes.

Single, axial CT image of the lungs demonstrates bilateral lower lobe airspace disease in a patient who had aspirated (solid black arrows). Aspiration usually affects the most dependent portions of the lung. In the upright position, the lower lobes are affected. In the recumbent position, the superior segments of the lower lobes and the posterior segments of the upper lobes are most involved. Aspiration of water or neutralized gastric acid will usually clear in 24-48 hours depending on the volume aspirated.

![]() Recognizing the different types of aspiration (Table 7-3)

Recognizing the different types of aspiration (Table 7-3)

The clinical and radiologic course of aspiration depends on what was aspirated.

The clinical and radiologic course of aspiration depends on what was aspirated.

TABLE 7-3 THREE PATTERNS OF ACUTE ASPIRATION

| Pattern | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Bland gastric acid or water | Rapidly appearing and rapidly clearing airspace disease in dependent lobe(s); not a pneumonia |

| Infected aspirate (aspiration pneumonia) | Usually lower lobes; frequently cavitates and may take months to clear |

| Unneutralized stomach acid (chemical pneumonitis) | Almost immediate appearance of dependent airspace disease that frequently becomes secondarily infected |

Localizing Pneumonia

An antibiotic will travel to every lobe of the lung without regard for which lobe actually harbors the pneumonia. But determining the location of a pneumonia may provide clues as to the causative organism (e.g., upper lobes, think of TB) and the presence of associated pathology (e.g., lower lobes, think of recurrent aspiration).

An antibiotic will travel to every lobe of the lung without regard for which lobe actually harbors the pneumonia. But determining the location of a pneumonia may provide clues as to the causative organism (e.g., upper lobes, think of TB) and the presence of associated pathology (e.g., lower lobes, think of recurrent aspiration). On conventional radiographs, it is always best to localize disease using two views taken at 90° to each other (orthogonal views) like a frontal and lateral chest radiograph. CT may further localize and characterize the disease as well as demonstrate associated pathology, such as pleural effusions or cavities too small to see on conventional radiographs.

On conventional radiographs, it is always best to localize disease using two views taken at 90° to each other (orthogonal views) like a frontal and lateral chest radiograph. CT may further localize and characterize the disease as well as demonstrate associated pathology, such as pleural effusions or cavities too small to see on conventional radiographs. Sometimes only a frontal radiograph may be available, as with critically ill or debilitated patients who require a portable bedside examination.

Sometimes only a frontal radiograph may be available, as with critically ill or debilitated patients who require a portable bedside examination. Nevertheless, it is still frequently possible to localize the pneumonia using only the frontal radiograph by analyzing which structure’s edges are obscured by the disease (i.e., the silhouette sign) (Table 7-4).

Nevertheless, it is still frequently possible to localize the pneumonia using only the frontal radiograph by analyzing which structure’s edges are obscured by the disease (i.e., the silhouette sign) (Table 7-4). Silhouette sign (see also Chapter 3 under “Characteristics of Airspace Disease”)

Silhouette sign (see also Chapter 3 under “Characteristics of Airspace Disease”)

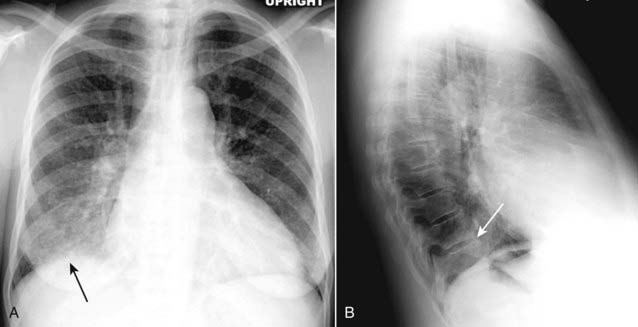

The spine sign (Fig. 7-11)

The spine sign (Fig. 7-11)

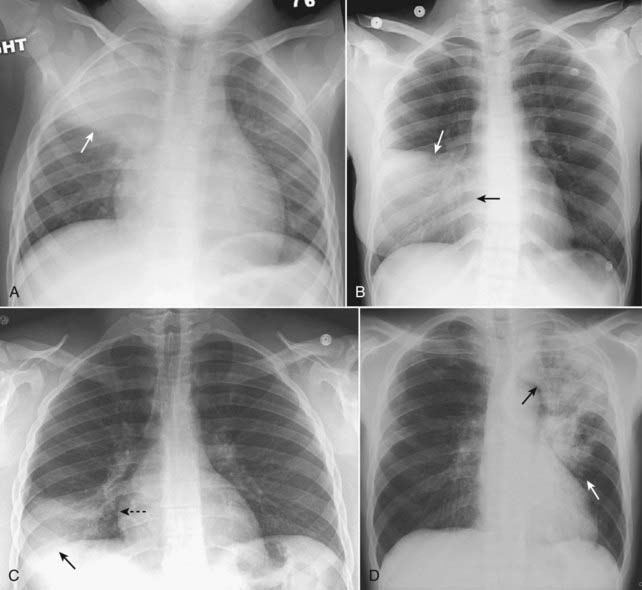

Figure 7-12 is a composite of the characteristic appearances of lobar pneumonia as seen on a frontal chest radiograph.

Figure 7-12 is a composite of the characteristic appearances of lobar pneumonia as seen on a frontal chest radiograph.TABLE 7-4 USING THE SILHOUETTE SIGN ON THE FRONTAL CHEST RADIOGRAPH

| Structure That Is No Longer Visible | Disease Location |

|---|---|

| Ascending aorta | Right upper lobe |

| Right heart border | Right middle lobe |

| Right hemidiaphragm | Right lower lobe |

| Descending aorta | Left upper or lower lobe |

| Left heart border | Lingula of left upper lobe |

| Left hemidiaphragm | Left lower lobe |

Frontal (A) and lateral (B) views of the chest demonstrate airspace disease on the lateral projection (B) in the right lower lobe that may not be immediately apparent on the frontal projection (you can see the pneumonia in the right lower lobe in (A) (solid black arrow). Normally, the thoracic spine appears to get “blacker” as you view it from the neck to the diaphragm because there is less tissue for the x-ray beam to traverse just above the diaphragm than in the region of the shoulder girdle (see also Fig. 2-3). In this case, a right lower lobe pneumonia superimposed on the lower spine in the lateral view (solid white arrow) makes the spine appear “whiter” (more dense) just above the diaphragm. This is called the spine sign.

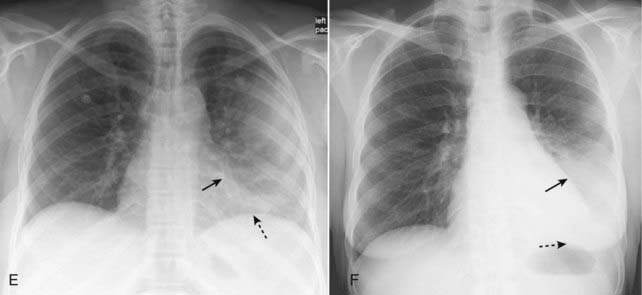

Figure 7-12 Composite appearances of lobar pneumonias.

A, Right upper lobe. The disease obscures (silhouettes) the ascending aorta. Where it abuts the minor fissure, it produces a sharp margin (white arrow). B, Right middle lobe. The disease silhouettes the right heart border (solid black arrow). Where it abuts the minor fissure, it produces a sharp margin (solid white arrow). C, Right lower lobe. The disease silhouettes the right hemidiaphragm (solid black arrow). It spares the right heart border (dotted black arrow). D, Left upper lobe. The disease is poorly marginated (solid white arrow) and obscures the aortic knob (solid black arrow). E, Lingula. The disease silhouettes the left heart border (solid black arrow) but spares the left hemidiaphragm (dotted black arrow). F, Left lower lobe. The disease obscures the left hemidiaphragm (dotted black arrow) but spares the left heart border (solid black arrow).

How Pneumonia Resolves

Pneumonia, especially pneumococcal pneumonia, can resolve in 2-3 days if the organism is sensitive to the antibiotic administered.

Pneumonia, especially pneumococcal pneumonia, can resolve in 2-3 days if the organism is sensitive to the antibiotic administered. Most pneumonias typically resolve from within (vacuolize), gradually disappearing in a patchy fashion over days or weeks (Fig. 7-13).

Most pneumonias typically resolve from within (vacuolize), gradually disappearing in a patchy fashion over days or weeks (Fig. 7-13). If a pneumonia does not resolve in several weeks, consider the presence of an underlying obstructing lesion, such as a neoplasm, that is preventing adequate drainage from that portion of the lung. A CT scan of the chest may help to demonstrate the obstructing lesion.

If a pneumonia does not resolve in several weeks, consider the presence of an underlying obstructing lesion, such as a neoplasm, that is preventing adequate drainage from that portion of the lung. A CT scan of the chest may help to demonstrate the obstructing lesion.

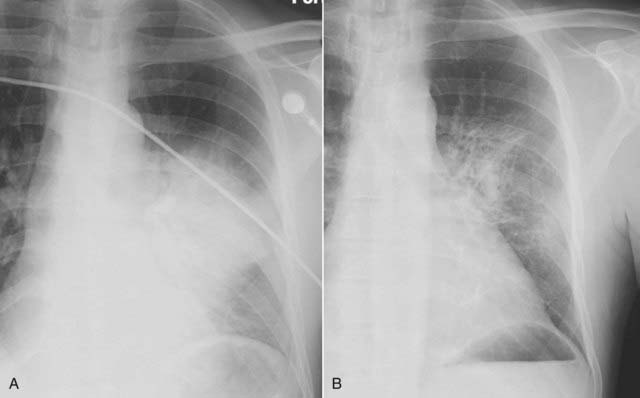

Figure 7-13 Resolving pneumonia.

Pneumonia, especially pneumococcal pneumonia, can resolve in 2-3 days if the organism is sensitive to the antibiotic administered. Most pneumonias, like that in the lingula in radiographs taken four days apart shown in (A) and (B), typically resolve from within (vacuolize), gradually disappearing in a patchy fashion over days or weeks. If a pneumonia does not resolve in weeks, you should consider the presence of an underlying obstructing lesion, such as a neoplasm, that is preventing adequate drainage from that portion of the lung.

Weblink

Weblink

Registered users may obtain more information on Recognizing Pneumonia on StudentConsult.com.

![]() Take-Home Points

Take-Home Points

Recognizing Pneumonia

Pneumonia is more opaque than the surrounding normal lung; its margins may be fluffy and indistinct except for where it abuts a pleural margin; it tends to be homogeneous in density; it may contain air bronchograms; it may be associated with atelectasis.

Although there is considerable overlap in the patterns of pneumonia that different organisms produce, some appearances are highly suggestive of particular etiologies.

Lobar pneumonia (prototype: pneumococcal pneumonia) tends to be homogeneous, occupies most or all of a lobe, has air bronchograms centrally and produces the silhouette sign.

Segmental pneumonia (prototype: staphylococcal pneumonia) tends to be multifocal, does not have air bronchograms, and can be associated with volume loss because the bronchi are also filled with inflammatory exudate.

Interstitial pneumonia (prototype: viral pneumonia or PCP) tends to involve the airway walls and alveolar septa and may produce, especially early in the course, a fine, reticular pattern in the lungs; later in the course, it produces airspace disease.

Round pneumonia (prototype: haemophilus) usually occurs in children in the lower lobes posteriorly and can resemble a mass, the clue being that masses in children are uncommon.

Cavitary pneumonia (prototype: tuberculosis) has lucent cavities produced by lung necrosis as its hallmark; post-primary tuberculosis usually involves the upper lobes; it can spread via a transbronchial route that can infect the opposite lower lobe or another lobe in the same lung.

Aspiration occurs in the most dependent portion of the lung at the time of the aspiration, usually the lower lobes or the posterior segments of the upper lobes; aspiration can be bland and clear quickly, can be infected and take months to clear, or may be from a chemical pneumonitis which can take weeks to clear.

Pneumonia can be localized by using the silhouette sign and the spine sign as aids.

Pneumonias frequently resolve by “breaking up” so that they contain patchy areas of newly aerated lung within the confines of the previous pneumonia (vacuolization).