Chapter 3 Recognizing Airspace Versus Interstitial Lung Disease

Classifying Parenchymal Lung Disease

Diseases that affect the lung can be arbitrarily divided into two main categories based in part on their pathology and in part on the pattern they typically produce on a chest imaging study.

Diseases that affect the lung can be arbitrarily divided into two main categories based in part on their pathology and in part on the pattern they typically produce on a chest imaging study.

Why learn the difference?

Why learn the difference?

Characteristics of Airspace Disease

![]() Airspace disease characteristically produces opacities in the lung that can be described as fluffy, cloudlike, or hazy.

Airspace disease characteristically produces opacities in the lung that can be described as fluffy, cloudlike, or hazy.

These fluffy opacities tend to be confluent, meaning they blend into one another with imperceptible margins.

These fluffy opacities tend to be confluent, meaning they blend into one another with imperceptible margins. The margins of airspace disease are indistinct, meaning it is frequently difficult to identify a clear demarcation point between the disease and the adjacent normal lung.

The margins of airspace disease are indistinct, meaning it is frequently difficult to identify a clear demarcation point between the disease and the adjacent normal lung. Airspace disease may be distributed throughout the lungs, as in pulmonary edema (Fig. 3-1), or it may appear to be more localized as in a segmental or lobar pneumonia (Fig. 3-2).

Airspace disease may be distributed throughout the lungs, as in pulmonary edema (Fig. 3-1), or it may appear to be more localized as in a segmental or lobar pneumonia (Fig. 3-2). Airspace disease may contain air bronchograms.

Airspace disease may contain air bronchograms.

Bronchi are normally not visible because their walls are very thin, they contain air, and they are surrounded by air. When something like fluid or soft tissue replaces the air normally surrounding the bronchus, then the air inside of the bronchus becomes visible as a series of black, branching tubular structures—this is the air bronchogram (Fig. 3-3).

Bronchi are normally not visible because their walls are very thin, they contain air, and they are surrounded by air. When something like fluid or soft tissue replaces the air normally surrounding the bronchus, then the air inside of the bronchus becomes visible as a series of black, branching tubular structures—this is the air bronchogram (Fig. 3-3). What can fill the airspaces besides air?

What can fill the airspaces besides air?

Figure 3-1 Diffuse airspace disease of pulmonary alveolar edema.

Opacities throughout both lungs primarily involve the upper lobes, which can be described as fluffy, hazy, or cloudlike and are confluent and poorly marginated, all pointing to airspace disease. This is a typical example of pulmonary alveolar edema (due to a heroin overdose in this patient).

Figure 3-2 Right lower lobe pneumonia.

An area of increased opacification is in the right midlung field (solid black arrow) that has indistinct margins (solid white arrow) characteristic of airspace disease. The minor fissure (dotted black arrow) appears to bisect the disease, locating this pneumonia in the superior segment of the right lower lobe. The right heart border and the right hemidiaphragm are still visible because the disease is not in anatomical contact with either of those structures.

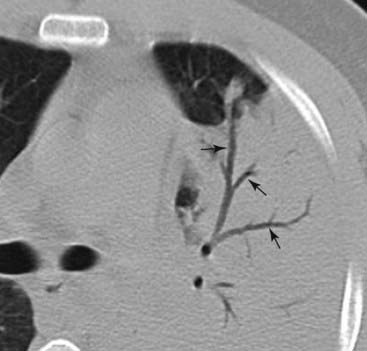

Figure 3-3 Air bronchograms demonstrated on CT scan.

Numerous black, branching structures (solid black arrows) represent air that is now visible inside the bronchi because the surrounding airspaces are filled with inflammatory exudate in this patient with an obstructive pneumonia from a bronchogenic carcinoma. Normally, on conventional radiographs, air inside bronchi is not visible because the bronchial walls are very thin, they contain air, and they are surrounded by air.

![]() Airspace disease may demonstrate the silhouette sign (Fig. 3-4).

Airspace disease may demonstrate the silhouette sign (Fig. 3-4).

The silhouette sign occurs when two objects of the same radiographic density (fat, water, etc.) touch each other so that the edge or margin between them disappears. It will be impossible to tell where one object begins and the other ends. The silhouette sign is valuable not only in the chest but as an aid in the analysis of imaging studies throughout the body.

The silhouette sign occurs when two objects of the same radiographic density (fat, water, etc.) touch each other so that the edge or margin between them disappears. It will be impossible to tell where one object begins and the other ends. The silhouette sign is valuable not only in the chest but as an aid in the analysis of imaging studies throughout the body.

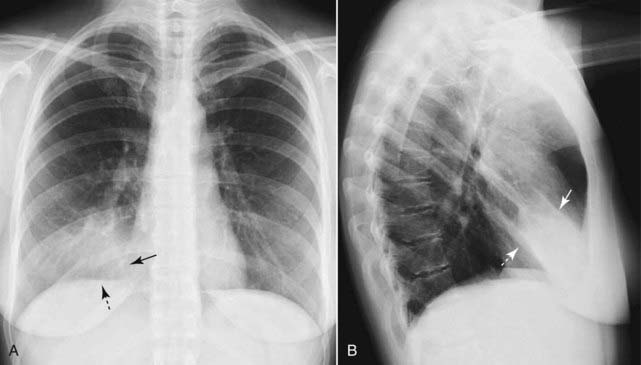

Figure 3-4 Silhouette sign, right middle lobe pneumonia.

A, Fluffy, indistinctly marginated airspace disease is seen to the right of the heart. It obscures the right heart border (solid black arrow) but not the right hemidiaphragm (dotted black arrow). This is called the silhouette sign and establishes that the disease (1) is in contact with the right heart border (which lies anteriorly in the chest) and (2) is the same radiographic density as the heart (fluid or soft tissue). Pneumonia fills the airspaces with an inflammatory exudate of fluid density. B, The area of the consolidation is indeed anterior, located in the right middle lobe, which is bound by the major fissure below (dotted white arrow) and the minor fissure above (solid white arrow).

Some Causes of Airspace Disease

Three of the many causes of airspace disease are highlighted here and will be described in greater detail later in the text.

Three of the many causes of airspace disease are highlighted here and will be described in greater detail later in the text. Pneumonia (see also Chapter 7)

Pneumonia (see also Chapter 7)

Pulmonary alveolar edema (see also Chapter 9)

Pulmonary alveolar edema (see also Chapter 9)

Aspiration (see also Chapter 7)

Aspiration (see also Chapter 7)

Figure 3-5 Right upper lobe pneumococcal pneumonia.

Close-up view of the right upper lobe demonstrates confluent airspace disease with air bronchograms (dotted white arrow). The inferior margin of the pneumonia is more sharply demarcated because it is in contact with the minor fissure (solid white arrow). This patient had Streptococcus pneumoniae cultured from the sputum.

Figure 3-6 Acute pulmonary alveolar edema.

Fluffy, bilateral, perihilar airspace disease with indistinct margins, sometimes described as having a bat-wing or angel-wing configuration, is present (solid white arrows). No air bronchograms are seen. The heart is enlarged. This represents pulmonary alveolar edema secondary to congestive heart failure.

Figure 3-7 Aspiration, right and left lower lobes.

An area of opacification in the right lower lobe is fluffy and confluent with indistinct margins characteristic of airspace disease (solid black arrow). To a much lesser extent, a similar density is seen in the left lower lobe (solid white arrow). The bibasilar distribution of this disease should raise the suspicion of aspiration as an etiology. This patient had a recent stroke and aspiration was demonstrated on a video swallowing study.

Characteristics of Interstitial Lung Disease

The lung’s interstitium consists of connective tissue, lymphatics, blood vessels, and bronchi. These are the structures that surround and support the airspaces.

The lung’s interstitium consists of connective tissue, lymphatics, blood vessels, and bronchi. These are the structures that surround and support the airspaces. Interstitial lung disease is sometimes referred to as infiltrative lung disease.

Interstitial lung disease is sometimes referred to as infiltrative lung disease.

![]() Interstitial lung disease produces what can be thought of as discrete “particles” of disease that develop in the abundant interstitial network of the lung (Fig. 3-8).

Interstitial lung disease produces what can be thought of as discrete “particles” of disease that develop in the abundant interstitial network of the lung (Fig. 3-8).

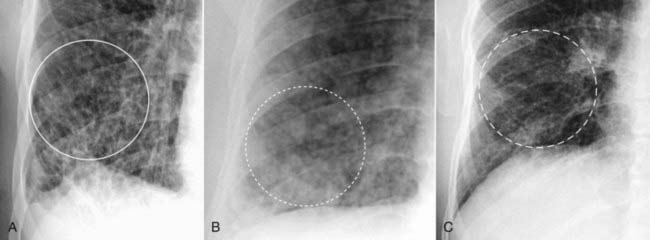

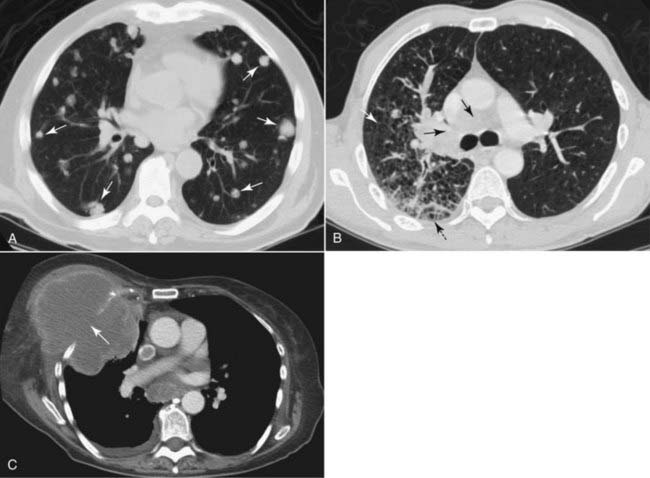

Figure 3-8 The patterns of interstitial lung disease.

A, The disease is primarily reticular in nature, consisting of crisscrossing lines (solid white circle). This patient had advanced sarcoidosis. B, The disease is predominantly nodular (dotted white circle). The patient was known to have thyroid carcinoma, and these nodules represent innumerable small metastatic foci in the lungs. C, Interstitial disease of the lung, reticulonodular. Most interstitial diseases of the lung have a mixture of both a reticular (lines) and nodular (dots) pattern, as does this case, which is a close-up view of the right lower lobe in another patient with sarcoidosis. The disease (dashed white circle) consists of both an intersecting, lacy network of lines and small nodules.

These “particles” or “packets” of interstitial disease tend to be inhomogeneous, separated from each other by visible areas of normally aerated lung.

These “particles” or “packets” of interstitial disease tend to be inhomogeneous, separated from each other by visible areas of normally aerated lung. The margins of “particles” of interstitial lung disease are sharper than the margins of airspace disease that tend to be indistinct.

The margins of “particles” of interstitial lung disease are sharper than the margins of airspace disease that tend to be indistinct. Interstitial lung disease can be focal (as in a solitary pulmonary nodule) or diffusely distributed in the lungs (Fig. 3-9).

Interstitial lung disease can be focal (as in a solitary pulmonary nodule) or diffusely distributed in the lungs (Fig. 3-9). Usually no air bronchograms are present, as there may be with airspace disease.

Usually no air bronchograms are present, as there may be with airspace disease.

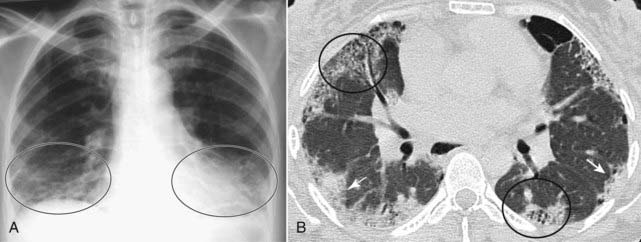

Figure 3-9 Varicella pneumonia.

Innumerable calcified granulomas occur in the lung interstitium, here seen as small, discrete nodules in the right lung (white circles). This patient had a history of varicella (chicken pox) pneumonia years earlier. Varicella pneumonia clears with multiple small calcified granulomas remaining.

![]() Pitfall: Sometimes, so much interstitial disease is present that the overlapping elements of disease may superimpose and mimic airspace disease on conventional chest radiographs. Remember that conventional radiographs are two-dimensional representations of three-dimensional objects (humans) so all of the densities in the lung, for example, are superimposed on themselves on any one projection. This may make the tiny packets of interstitial disease seem coalescent and more like airspace disease.

Pitfall: Sometimes, so much interstitial disease is present that the overlapping elements of disease may superimpose and mimic airspace disease on conventional chest radiographs. Remember that conventional radiographs are two-dimensional representations of three-dimensional objects (humans) so all of the densities in the lung, for example, are superimposed on themselves on any one projection. This may make the tiny packets of interstitial disease seem coalescent and more like airspace disease.

Figure 3-10 The edge of the lesion.

Notice how a portion of this disease appears confluent, like airspace disease (solid black arrow). Always look at the peripheral margins of parenchymal lung disease to best determine the nature of the “packets” of abnormality and to help in differentiating airspace disease from interstitial disease. At the periphery of this disease (black circle), this is more clearly seen to be reticular interstitial disease.

Some Causes of Interstitial Lung Disease

Just as with the airspace pattern, there are many diseases that produce an interstitial pattern in the lung. Several will be discussed briefly here. They are roughly divided into those diseases that are predominantly reticular and those that are predominantly nodular.

Just as with the airspace pattern, there are many diseases that produce an interstitial pattern in the lung. Several will be discussed briefly here. They are roughly divided into those diseases that are predominantly reticular and those that are predominantly nodular.

![]() Keep in mind that many diseases have patterns that overlap and many interstitial lung diseases have mixtures of both reticular and nodular changes (reticulonodular disease).

Keep in mind that many diseases have patterns that overlap and many interstitial lung diseases have mixtures of both reticular and nodular changes (reticulonodular disease).

Predominantly Reticular Interstitial Lung Diseases

Pulmonary interstitial edema

Pulmonary interstitial edema

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

Rheumatoid lung

Rheumatoid lung

Figure 3-11 Pulmonary interstitial edema secondary to congestive heart failure.

A close-up view of the right lung shows an accentuation of the pulmonary interstitial markings (black circle). Multiple Kerley B lines (white circle) represent fluid in thickened interlobular septa. Fluid is seen in the inferior accessory fissure (solid black arrow).

Figure 3-12 Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis probably represents a spectrum of disease that may begin as desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP) and lead to the findings here of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP). A, coarse reticular interstitial markings represent fibrosis, predominantly at the lung bases (black circles). B, A high-resolution CT scan of the chest shows abnormalities at the lung bases in a subpleural location, the typical distribution for UIP. There are small cystic spaces called honeycombing (black circles) with hazy densities called ground-glass opacities (solid white arrows).

Prominent markings at both lung bases have a predominantly reticular appearance (solid white arrows). Bibasilar interstitial disease can be found in numerous diseases including bronchiectasis, asbestosis, desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP), scleroderma, and sickle cell disease. This patient was known to have rheumatoid arthritis. Pleural effusion is the most common manifestation of rheumatoid lung disease, and pulmonary fibrosis, usually diffuse but more prominent at the bases, is second most common.

Predominantly Nodular Interstitial Diseases

Bronchogenic carcinoma (see Chapter 12)

Bronchogenic carcinoma (see Chapter 12)

Metastases to the lung

Metastases to the lung

Figure 3-14 Adenocarcinoma, right upper lobe.

A mass is seen in the right upper lobe (solid white arrow). Its margin is slightly indistinct along the superolateral border (solid black arrow). CT scan of the chest confirmed the presence of the mass and also demonstrated paratracheal and right hilar adenopathy. The mass was biopsied and was an adenocarcinoma, primary to the lung. Adenocarcinoma of the lung most commonly presents as a peripheral nodule.

Figure 3-15 Metastases to the lung, CT scans.

A, Multiple discrete nodules of varying size are present throughout both lungs (solid white arrows). The diagnosis of exclusion, whenever multiple nodules are found in the lungs, is metastatic disease. In this case, the metastases were from colon carcinoma. B, The interstitial markings in the right lung are prominent (solid white arrow), there are septal lines (dotted black arrow) and lymphadenopathy (solid black arrows) from lymphangitic spread of a bronchogenic carcinoma. C, In this case, the lung cancer has grown through the chest wall (solid white arrow) and invaded it by direct extension. The pleura usually serves as a strong barrier to the direct spread of tumor.

Mixed Reticular and Nodular Interstitial Disease (Reticulonodular Disease)

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis

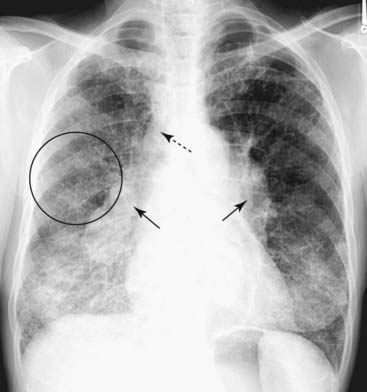

A frontal radiograph of the chest reveals bilateral hilar (solid black arrows) and right paratracheal adenopathy (dotted black arrow), a classical distribution for the adenopathy in sarcoidosis. In addition, the patient has diffuse, bilateral interstitial lung disease (black circle) that is reticulonodular in nature. In some patients with this stage of disease, the adenopathy regresses while the interstitial disease remains. In the overwhelming majority of patients with sarcoid, the disease completely resolves.

Weblink

Weblink

Registered users may obtain more information on Recognizing Airspace Versus Interstitial Lung Disease on StudentConsult.com.

![]() Take-Home Points

Take-Home Points

Recognizing Airspace Versus Interstitial Lung Disease

Parenchymal lung disease can be divided into airspace (alveolar) and interstitial (infiltrative) patterns.

Recognizing the pattern of disease can help in reaching the correct diagnosis.

Characteristics of airspace disease include fluffy, confluent densities that are indistinctly marginated and may demonstrate air bronchograms.

Characteristics of interstitial lung disease include discrete “particles” or “packets” of disease with distinct margins that tend to occur in a pattern of lines (reticular), dots (nodular), or very frequently a combination of lines and dots (reticulonodular).

Examples of airspace disease include pulmonary alveolar edema, pneumonia, and aspiration.

Examples of interstitial lung disease include pulmonary interstitial edema, pulmonary fibrosis, metastases to the lung, bronchogenic carcinoma, sarcoidosis, and rheumatoid lung.

An air bronchogram is typically a sign of airspace disease and occurs when something other than air (such as inflammatory exudate or blood) surrounds the bronchus, allowing the air inside the bronchus to become visible.

When two objects of the same radiographic density are in contact with each other, the normal edge or margin between them will disappear. The disappearance of the margin between these two structures is called the silhouette sign and is useful throughout radiology in identifying either the location or the density of the abnormality in question.