Chapter 14 Recognizing Bowel Obstruction and Ileus

In this chapter, you’ll learn how to recognize and categorize the four most common abnormal bowel gas patterns and their causes. These abnormal bowel gas patterns will appear the same whether imaged initially by conventional radiography or by CT scanning. CT is superior in revealing the location, degree, and cause of an obstruction and in demonstrating any signs of reduced bowel viability.

In this chapter, you’ll learn how to recognize and categorize the four most common abnormal bowel gas patterns and their causes. These abnormal bowel gas patterns will appear the same whether imaged initially by conventional radiography or by CT scanning. CT is superior in revealing the location, degree, and cause of an obstruction and in demonstrating any signs of reduced bowel viability.Abnormal Gas Patterns

Abnormal intestinal gas patterns can be divided into two main categories, each of which can be subdivided into two subcategories (Box 14-1).

Abnormal intestinal gas patterns can be divided into two main categories, each of which can be subdivided into two subcategories (Box 14-1). Functional ileus is one main category in which it is presumed that one or more loops of bowel lose their ability to propagate the peristaltic waves of the bowel, usually due to some local irritation or inflammation, and hence cause a functional type of “obstruction” proximal to the affected loop(s).

Functional ileus is one main category in which it is presumed that one or more loops of bowel lose their ability to propagate the peristaltic waves of the bowel, usually due to some local irritation or inflammation, and hence cause a functional type of “obstruction” proximal to the affected loop(s). There are two kinds of functional ileus.

There are two kinds of functional ileus.

Mechanical obstruction is the other main category of abnormal bowel gas pattern. With mechanical obstruction, a physical, organic, obstructing lesion prevents the passage of intestinal content past the point of either the small or large bowel blockage.

Mechanical obstruction is the other main category of abnormal bowel gas pattern. With mechanical obstruction, a physical, organic, obstructing lesion prevents the passage of intestinal content past the point of either the small or large bowel blockage.Laws Of The Gut

Peristalsis will continue (except in the loops of bowel involved in a functional ileus) in an attempt to propel intestinal contents through the bowel.

Peristalsis will continue (except in the loops of bowel involved in a functional ileus) in an attempt to propel intestinal contents through the bowel. Loops distal to an obstruction will eventually become decompressed or airless, as their contents are evacuated.

Loops distal to an obstruction will eventually become decompressed or airless, as their contents are evacuated. In a mechanical obstruction, the loop(s) that will become the most dilated will either be the loop of bowel with the largest resting diameter before the onset of the obstruction (e.g., the cecum in the large bowel), or the loop(s) of bowel just proximal to the obstruction.

In a mechanical obstruction, the loop(s) that will become the most dilated will either be the loop of bowel with the largest resting diameter before the onset of the obstruction (e.g., the cecum in the large bowel), or the loop(s) of bowel just proximal to the obstruction. Most patients with a mechanical obstruction will present with some form of abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and constipation.

Most patients with a mechanical obstruction will present with some form of abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and constipation.

Prolonged obstruction with persistently elevated intraluminal pressures can lead to vascular compromise, necrosis and perforation in the affected loop of bowel.

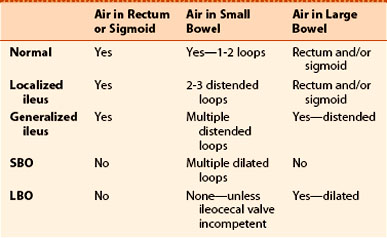

Prolonged obstruction with persistently elevated intraluminal pressures can lead to vascular compromise, necrosis and perforation in the affected loop of bowel. Let’s look at each of the four abnormal bowel gas patterns in detail (Table 14-1). For each of the four abnormalities, we’ll look at their pathophysiology, causes, key imaging features, and diagnostic pitfalls.

Let’s look at each of the four abnormal bowel gas patterns in detail (Table 14-1). For each of the four abnormalities, we’ll look at their pathophysiology, causes, key imaging features, and diagnostic pitfalls.Functional Ileus, Localized: Sentinel Loops

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

Causes of a localized ileus

Causes of a localized ileus

Key imaging features of a localized ileus

Key imaging features of a localized ileus

TABLE 14-2 CAUSES OF A LOCALIZED ILEUS

| Site of Dilated Loops | Cause(s) |

|---|---|

| Right upper quadrant | Cholecystitis |

| Left upper quadrant | Pancreatitis |

| Right lower quadrant | Appendicitis |

| Left lower quadrant | Diverticulitis |

| Midabdomen | Ulcer or kidney/ureteral calculus |

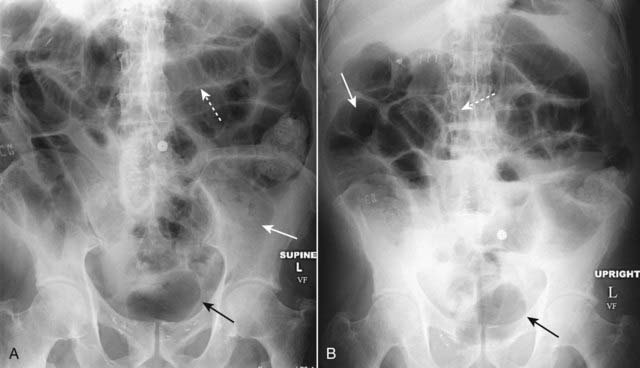

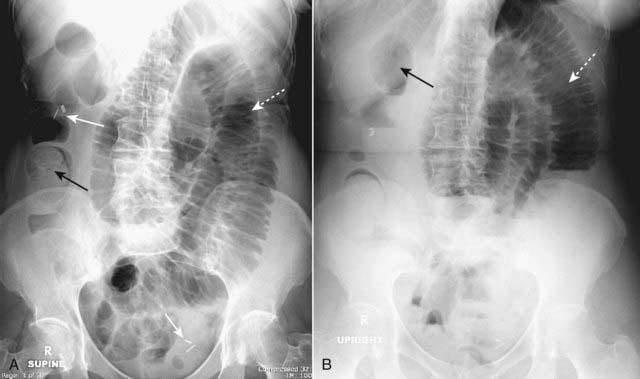

Figure 14-1 Sentinel loops from pancreatitis.

A single, persistently dilated loop of small bowel is seen in the left upper quadrant (solid white arrows) on both the supine (A) and prone (B) radiographs of the abdomen. A sentinel loop or localized ileus often signals the presence of an adjacent irritative or inflammatory process. This patient had acute pancreatitis.

![]() Pitfalls: Differentiating a localized ileus from an early SBO

Pitfalls: Differentiating a localized ileus from an early SBO

![]() Solution. A combination of the clinical and laboratory findings and CT scanning of the abdomen that demonstrates the underlying pathology should differentiate localized ileus from small bowel obstruction.

Solution. A combination of the clinical and laboratory findings and CT scanning of the abdomen that demonstrates the underlying pathology should differentiate localized ileus from small bowel obstruction.

Functional Ileus, Generalized: Adynamic Ileus

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

Key imaging features of a generalized adynamic ileus

Key imaging features of a generalized adynamic ileus

TABLE 14-3 CAUSES OF A GENERALIZED ADYNAMIC ILEUS

| Cause | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Postoperative | Usually abdominal surgery |

| Electrolyte imbalance | Especially diabetics in ketoacidosis |

Mechanical Obstruction: Small Bowel Obstruction (Sbo)

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

Key imaging features of mechanical small bowel obstruction

Key imaging features of mechanical small bowel obstruction

TABLE 14-4 CAUSES OF A MECHANICAL SMALL BOWEL OBSTRUCTION

| Cause | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Postsurgical adhesions | Most common cause of a small bowel obstruction; most frequently following appendectomy, colorectal surgery and pelvic surgery; transition point on small bowel CT without other identifying cause most likely represents adhesions |

| Malignancy | Primary malignancies of the small bowel are rare; secondary tumors such as gastric and colonic carcinomas and ovarian cancers may compromise the lumen of small bowel |

| Hernia | An inguinal hernia may be visible on conventional radiographs if air-containing loops of bowel are seen over the obturator foramen; easily seen on CT (see Fig. 14-3). |

| Gallstone ileus | May be visible on conventional radiographs or CT if air is seen in the biliary tree and (rarely) a gallstone is present in RLQ (see Chapter 15) |

| Intussusception | Ileocolic intussusception is the most common form and produces SBO |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Thickening of the bowel wall may occur with compromise of the lumen in patients with Crohn disease; this is most likely to occur in the terminal ileum |

Figure 14-3 Small bowel obstruction from inguinal hernia.

A, The scout image from a CT scan of the abdomen reveals dilated loops of small bowel (solid black arrow) caused by a left inguinal hernia (white circle). Loops of bowel should normally not be present in the scrotum. B, Coronal-reformatted CT scan on another patient shows multiple fluid-filled and dilated loops of small bowel (solid white arrows) from a right inguinal hernia (white circle) containing another dilated loop of small bowel (dotted white arrow).

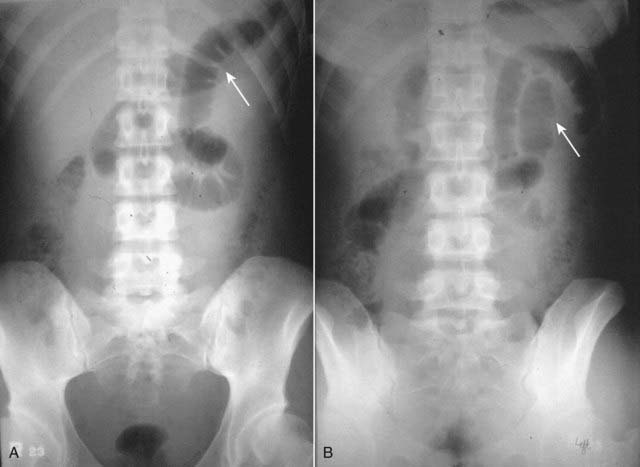

Figure 14-4 Step-ladder appearance of obstructed small bowel.

As they begin to dilate, small bowel loops stack up, forming a step-ladder appearance usually beginning in the left upper quadrant and proceeding, depending on how distal the small bowel obstruction is, to the right lower quadrant (solid black arrows). The more proximal the small bowel obstruction (e.g., proximal jejunum), the fewer the dilated loops there will be; the more distal the obstruction (e.g., at the ileocecal valve), the greater the number of dilated small bowel loops. This was a distal small bowel obstruction caused by a carcinoma of the colon which obstructed the ileocecal valve.

![]() In a mechanical small bowel obstruction, there should always be a disproportionate dilatation of small bowel compared to the collapsed large bowel (Fig. 14-5).

In a mechanical small bowel obstruction, there should always be a disproportionate dilatation of small bowel compared to the collapsed large bowel (Fig. 14-5).

Figure 14-5 Mechanical small bowel obstruction.

Even though there is still a small amount of air visible in the right colon (solid white arrow), the overall bowel gas pattern is one of disproportionate dilation of multiple loops of small bowel (solid black arrows) consistent with a mechanical small bowel obstruction. The obstruction was presumably secondary to adhesions.

![]() Pitfalls: Differentiating a partial SBO from a functional (localized) adynamic ileus

Pitfalls: Differentiating a partial SBO from a functional (localized) adynamic ileus

CT is the most sensitive study for diagnosing the site and cause of a mechanical small bowel obstruction.

CT is the most sensitive study for diagnosing the site and cause of a mechanical small bowel obstruction.

The CT findings of a small bowel obstruction:

The CT findings of a small bowel obstruction:

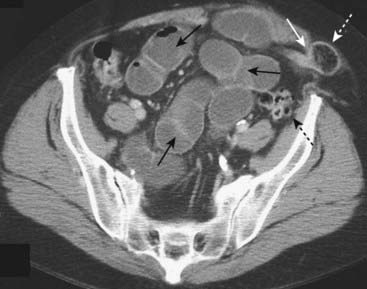

Figure 14-6 Partial small bowel obstruction, supine (A) and upright (B).

A partial or incomplete mechanical small bowel obstruction allows some gas to pass the point of obstruction, possibly on an intermittent basis. This can lead to a confusing picture because gas may pass into the colon (solid black arrows) and be visible long after the large bowel would be expected to be devoid of gas. The important observation is that the small bowel is disproportionately dilated (dotted white arrows) compared to the large bowel, a finding suggestive of small bowel obstruction. Partial or incomplete small bowel obstructions occur more often in patients in whom adhesions are the etiology. Notice the clips (solid white arrows) attesting to prior surgery.

Figure 14-7 Partial small bowel obstruction.

Coronal-reformatted CT scan with oral contrast shows dilated and contrast-containing loops of small bowel (solid white arrows). Although there is still air present in the collapsed colon (dotted white arrows), the disproportionate dilatation of small bowel identifies this as a small bowel obstruction.

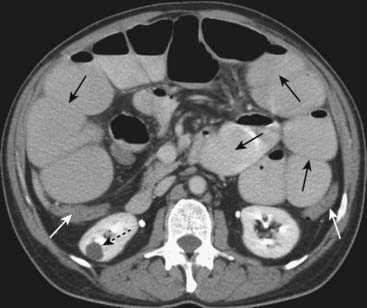

Figure 14-8 Small bowel obstruction due to Spigelian hernia.

A Spigelian hernia occurs at the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis muscle at the semilunar line. This patient has a transition point (solid white arrow) as the small bowel enters the hernia (dotted white arrow). More proximally, there are multiple dilated loops of small bowel (solid black arrows) that indicate obstruction. The colon is beyond the point of obstruction and is collapsed (dotted black arrow).

Figure 14-9 Small bowel obstruction, CT with oral and IV contrast.

There are multiple fluid- and contrast-filled, dilated loops of small bowel demonstrated (solid black arrows), while the colon is collapsed (solid white arrows), indicating a small bowel obstruction. Bowel wall enhancement or lack thereof may be obscured by oral contrast, a drawback to the use of oral contrast. Incidentally noted is a right renal cyst (dotted black arrow).

Figure 14-10 Small bowel feces sign.

There is air mixed with debris and old oral contrast in a dilated loop of small bowel (solid white arrows). There are proximal fluid-containing, dilated loops of small bowel (dotted white arrows). The patient had a CT scan with oral contrast several days earlier for abdominal pain and returned for this noncontrast scan when symptoms persisted. Intestinal debris and fluid may accumulate in the loop usually just proximal to a small bowel obstruction and produce this finding which resembles fecal material in the colon.

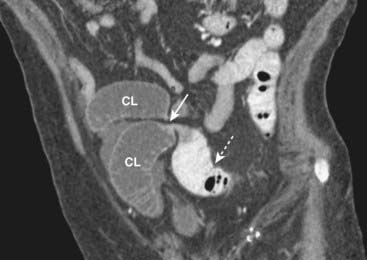

Figure 14-11 Closed-loop obstruction, CT.

A loop of small bowel (CL) is obstructed twice at the same point of twist (solid white arrow) producing a closed loop. No oral contrast enters the closed loop but is present in a more proximal loop of small bowel (dotted white arrow). Closed-loop obstructions are important because of their higher incidence of necrosis from strangulation of the bowel.

Figure 14-12 Bowel necrosis, contrast-enhanced CT.

A dilated loop of small bowel demonstrates normal enhancement of the wall (solid white arrow) on this coronal reformat of a contrast-enhanced CT, while more distal, dilated loops of small bowel show no wall enhancement (black circle). This is an indication of vascular compromise of the distal loops with bowel necrosis.

Mechanical Obstruction: Large Bowel Obstruction (Lbo)

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

Causes of a mechanical large bowel obstruction are summarized in Table 14-5.

Causes of a mechanical large bowel obstruction are summarized in Table 14-5.

TABLE 14-5 CAUSES OF A MECHANICAL LARGE BOWEL OBSTRUCTION

| Cause | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Tumor (carcinoma) | Most common cause of LBO; more frequently obstructs when it involves the left colon |

| Hernia | May be visible on conventional radiographs if air is seen over the obturator foramen |

| Volvulus | Either the sigmoid (more common) or cecum may twist on its axis and obstruct the colon and small bowel (Box 14-2) |

| Diverticulitis | Uncommon cause of colonic obstruction |

| Intussusception | Colocolic intussusception usually occurs because of a tumor acting as a lead point |

![]() Key imaging features of a mechanical large bowel obstruction

Key imaging features of a mechanical large bowel obstruction

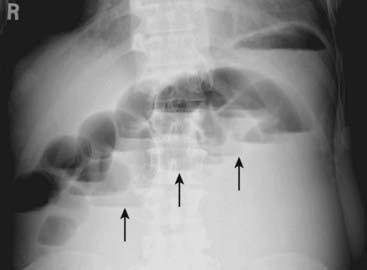

Figure 14-13 Mechanical large bowel obstruction.

The entire colon is dilated (dotted white arrows) to a cut-off point in the distal descending colon (solid white arrow), the site of this patient’s obstructing carcinoma of the colon. Some gas has passed backwards through an incompetent ileocecal valve and outlines a dilated ileum (solid black arrow). Notice that the large bowel is disproportionately dilated compared to the small bowel, a finding of large bowel obstruction.

So long as the ileocecal valve prevents gas from reentering the small bowel in a retrograde direction (such an ileocecal valve is called competent), the colon will continue to dilate between the ileocecal valve and the point of colonic obstruction. The small bowel is not dilated.

So long as the ileocecal valve prevents gas from reentering the small bowel in a retrograde direction (such an ileocecal valve is called competent), the colon will continue to dilate between the ileocecal valve and the point of colonic obstruction. The small bowel is not dilated.

Recognizing a large bowel obstruction on CT

Recognizing a large bowel obstruction on CT

Figure 14-14 Large bowel obstruction masquerading as a small bowel obstruction.

There are air-filled and dilated loops of small bowel (solid white arrows) seen in this patient who had a mechanical large bowel obstruction from a carcinoma of the middescending colon. The pressure in the colon was sufficient to open the ileocecal valve, which then allowed much of the gas in the colon to decompress backward into the small bowel. The cecum still contains air (dotted white arrow) and is dilated, a clue that this is really a large bowel obstruction. Abdominal CT can resolve the question of whether the large or small bowel is obstructed.

Figure 14-15 Large bowel obstruction from carcinoma of the colon.

This coronal reformatted CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis shows dilated cecum (dotted white arrow) and large bowel (LB) to the level of the distal descending colon where a large soft tissue mass is identified (solid white arrow). This mass was surgically removed and was an adenocarcinoma of the colon.

Volvulus Of The Colon

Volvulus of the colon is a particular kind of large bowel obstruction that produces a striking and characteristic picture that is summarized in Box 14-2 (Fig. 14-16).

Volvulus of the colon is a particular kind of large bowel obstruction that produces a striking and characteristic picture that is summarized in Box 14-2 (Fig. 14-16).Box 14-2 Volvulus

A Cause of Mechanical Large Bowel Obstruction

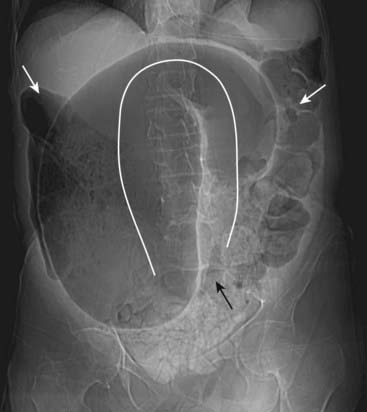

Figure 14-16 Sigmoid volvulus, supine abdomen.

There is a massively dilated sigmoid colon (solid white line) twisted upon itself in the pelvis (solid black arrow). The dilated sigmoid has a coffee-bean shape. Since the point of obstruction is in the distal colon, there are air and stool present in the more proximal portion of the colon (solid white arrows). Volvulus can produce massively dilated loops of sigmoid colon.

Intestinal Pseudo-Obstruction (Ogilvie Syndrome)

Ogilvie syndrome (acute intestinal pseudo-obstruction) may occur in elderly individuals who are usually already hospitalized or at chronic bed rest.

Ogilvie syndrome (acute intestinal pseudo-obstruction) may occur in elderly individuals who are usually already hospitalized or at chronic bed rest.

The syndrome is characterized by a loss of peristalsis, resulting in sometimes massive dilatation of the entire colon resembling a large bowel obstruction (Fig. 14-17).

The syndrome is characterized by a loss of peristalsis, resulting in sometimes massive dilatation of the entire colon resembling a large bowel obstruction (Fig. 14-17).

Management is pharmacologic stimulation of colonic contractions, usually with drugs such as neostigmine.

Management is pharmacologic stimulation of colonic contractions, usually with drugs such as neostigmine.

Figure 14-17 Ogilvie syndrome.

Ogilvie syndrome (acute intestinal pseudo-obstruction) may occur in elderly individuals who are usually already hospitalized or at chronic bed rest. Drugs with anticholinergic effects may cause or exacerbate the condition. The syndrome is characterized by a loss of peristalsis, resulting in sometimes massive dilatation of the entire colon resembling a large bowel obstruction, as in this patient. Treatment is pharmacologic stimulation of the bowel.

Weblink

Weblink

Registered users may obtain more information on Recognizing Bowel Obstruction and Ileus on StudentConsult.com.

![]() Take-Home Points

Take-Home Points

Recognizing Bowel Obstruction and Ileus

Abnormal bowel gas patterns can be divided into two main groups: functional ileus and mechanical obstruction.

There are two varieties of functional ileus: localized ileus (sentinel loops) and generalized adynamic ileus. There are two varieties of mechanical obstruction: small bowel obstruction (SBO) and large bowel obstruction (LBO).

In mechanical obstruction, the gut reacts in predictable ways: loops proximal to the obstruction become dilated, peristalsis attempts to propel intestinal contents through the bowel and loops distal to the obstruction eventually are evacuated; the loop(s) that become the most dilated will either be the loop of bowel with the largest resting diameter or the loop(s) of bowel just proximal to the obstruction.

The key findings in a localized ileus (sentinel loops) are 2-3 dilated loops of small bowel with air in the rectosigmoid and an underlying irritative process that frequently is adjacent to the dilated loops.

Some causes of sentinel loops include pancreatitis (LUQ), cholecystitis (RUQ), diverticulitis (LLQ) and appendicitis (RLQ). All can be readily identified using ultrasound or CT.

The key findings in a generalized adynamic ileus are dilated loops of large and small bowel with gas in the rectosigmoid and long, air-fluid levels. Post-operative patients develop generalized adynamic ileus.

The key imaging findings in a mechanical small bowel obstruction are disproportionately dilated and fluid-filled loops of small bowel with little or no gas in the recto-sigmoid. CT is best at identifying the cause and site of obstruction or its complications.

The most common cause of a SBO is adhesions; other causes include hernias, intussusception, gallstone ileus, malignancy, and inflammatory bowel disease, such as Crohn disease.

A closed-loop obstruction is one in which two points of the bowel are obstructed in the same location producing the “closed-loop.” In the small bowel, a closed-loop obstruction carries a higher risk of strangulation of the bowel. In the large bowel, a closed-loop obstruction is called a volvulus.

The key imaging findings in mechanical LBO include dilatation of the colon to the point of the obstruction and absence of gas in the rectum with no dilatation of the small bowel as long as the ileocecal valve remains competent. CT will often demonstrate the cause of the obstruction.

Causes of mechanical LBO include malignancy, hernia, diverticulitis, and intussusception.

Ogilvie syndrome is characterized by a loss of peristalsis, resulting in sometimes massive dilatation of the entire colon resembling a large bowel obstruction but without a demonstrable point of obstruction; it can sometimes be confused for a generalized adynamic ileus.