Chapter 16 Recognizing Abnormal Calcifications and Their Causes

Soft tissue calcifications lend themselves to an intuitive approach that ties together a diverse group of diseases. While this chapter focuses primarily on abdominal calcifications, the same principles and approach apply to dystrophic calcifications found anywhere in the body.

Soft tissue calcifications lend themselves to an intuitive approach that ties together a diverse group of diseases. While this chapter focuses primarily on abdominal calcifications, the same principles and approach apply to dystrophic calcifications found anywhere in the body. Dystrophic calcification is soft tissue calcification that occurs in tissue that is already abnormal. (Metastatic calcification, by contrast, is calcification in otherwise normal soft tissues due to disturbances in calcium/phosphorus metabolism.)

Dystrophic calcification is soft tissue calcification that occurs in tissue that is already abnormal. (Metastatic calcification, by contrast, is calcification in otherwise normal soft tissues due to disturbances in calcium/phosphorus metabolism.) On conventional radiographs, the nature of most calcifications can be determined by examining their pattern of calcification and their anatomic location.

On conventional radiographs, the nature of most calcifications can be determined by examining their pattern of calcification and their anatomic location. The same principles hold true for CT evaluation of calcifications except that the anatomic location is usually easier to determine on CT.

The same principles hold true for CT evaluation of calcifications except that the anatomic location is usually easier to determine on CT.Rimlike Calcification

Examples of structures that manifest rimlike calcifications:

Examples of structures that manifest rimlike calcifications:

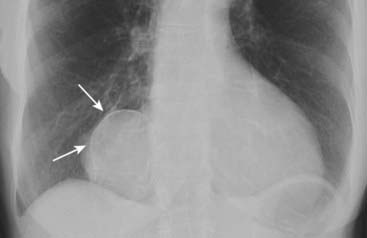

Figure 16-1 Calcified pericardial cyst.

There is a rimlike calcification (solid white arrows) that identifies the structure containing the calcification as cystic or saccular. The calcification is in the right cardiophrenic angle, an ideal location for pericardial cysts. Pericardial cysts are usually asymptomatic and discovered when a chest radiograph is obtained for another reason.

Figure 16-2 Calcified aortic aneurysm.

Calcification in the wall of the abdominal aorta is a common finding in atherosclerosis, especially in those with diabetes mellitus. In this patient, the aorta is enlarged and demonstrates a rimlike calcification (solid white arrows). The opposing wall is also calcified, but overlaps the spine. An aneurysm is present when the diameter of the abdominal aorta exceeds its normal diameter by more than 50%.

Figure 16-3 Calcified gallbladder wall.

The rimlike calcification (solid white arrow) identifies this as occurring in the wall of a cyst or saccular organ. The calcification is in the right upper quadrant, the location of the gallbladder. This is a porcelain gallbladder, an uncommon entity (named after the gross appearance of the gallbladder which resembles porcelain) that occurs with chronic inflammation and stasis and is associated with gallstones and an increased incidence of carcinoma of the gallbladder.

TABLE 16-1 RIMLIKE CALCIFICATIONS

| Organ of Origin | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Renal cyst | Thick and irregular calcifications, though uncommon, may indicate the presence of renal cell carcinoma. |

| Splenic cysts | May be a manifestation of hydatid cyst, old trauma, or prior infection. |

| Aortic aneurysms | Occurs more often in diabetics with advanced atherosclerosis. |

| Gallbladder | Associated with chronic stasis; called porcelain gallbladder for its gross appearance; higher incidence of carcinoma of the gallbladder. |

Linear Or Tracklike Calcification

Linear or tracklike calcifications imply calcification that has occurred in the walls of tubular structures (Fig. 16-4).

Linear or tracklike calcifications imply calcification that has occurred in the walls of tubular structures (Fig. 16-4). Examples include calcifications in the walls of:

Examples include calcifications in the walls of:

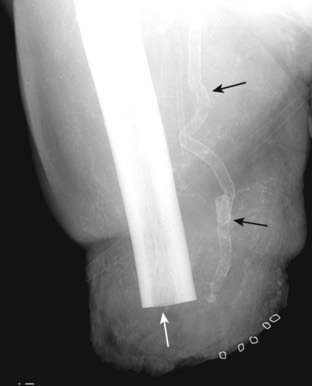

Figure 16-4 Calcified arterial wall.

There is linear or tracklike calcification present (solid black arrows), which implies calcification that has occurred in the walls of tubular structures. In the leg, this is calcification in the femoral artery. Such wall calcification occurs in arteries, not veins, and is usually secondary to atherosclerosis, frequently associated with diabetes, or in patients with chronic renal disease. This patient obviously suffered one of the complications of diabetes and has had an above-the-knee amputation (solid white arrow) of a formerly gangrenous leg.

Figure 16-5 Calcification of the vas deferens.

This patient manifests two tracklike calcifications (solid black arrows) symmetrically on each side of the urinary bladder that end in the urethra in this man who also has an enlarged prostate which is elevating the base of the bladder. This type of calcification identifies it as occurring in the wall of a tubular structure. The location identifies it as calcification in the walls of the vas deferens, which occurs more commonly and earlier in diabetics than as a natural degenerative process.

TABLE 16-2 LINEAR OR TRACKLIKE CALCIFICATIONS

| Organ of Origin | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Walls of smaller arteries | Mostly seen in atherosclerosis accelerated by diabetes and renal disease |

| Fallopian tubes or vas deferens | Usually accelerated by diabetes |

| Ureters | Uncommon occurrence described with schistosomiasis and rarely TB |

Lamellar Or Laminar Calcification

Lamellar (or laminar) calcifications imply calcification that forms around a nidus inside a hollow lumen (Fig. 16-6).

Lamellar (or laminar) calcifications imply calcification that forms around a nidus inside a hollow lumen (Fig. 16-6).

Lamellar or laminated calcifications are usually called stones or calculi (singular: calculus) and include renal and ureteral calculi.

Lamellar or laminated calcifications are usually called stones or calculi (singular: calculus) and include renal and ureteral calculi.

Recognizing a calculus on a stone search study (all signs discussed are on the symptomatic side):

Recognizing a calculus on a stone search study (all signs discussed are on the symptomatic side):

Gallstones. Ultrasound is the study of choice (see Chapter 19). Only about 10% to 15% of gallstones contain enough calcification to be visible on conventional radiographs (Fig. 16-9).

Gallstones. Ultrasound is the study of choice (see Chapter 19). Only about 10% to 15% of gallstones contain enough calcification to be visible on conventional radiographs (Fig. 16-9). Bladder stones usually develop secondary to chronic bladder outlet obstruction. They are very prone to develop lamination (Fig. 16-10).

Bladder stones usually develop secondary to chronic bladder outlet obstruction. They are very prone to develop lamination (Fig. 16-10).

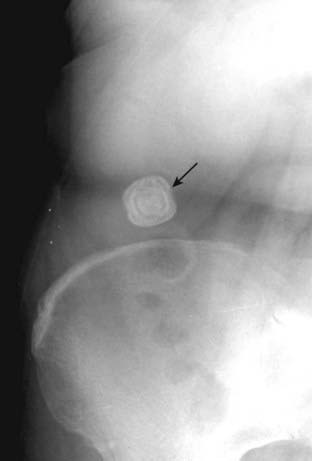

Figure 16-6 Calcified gallstone.

There is a lamellated calcification present in the right upper quadrant (solid black arrow). The lamination identifies it as a calculus that has formed in a hollow viscus. The anatomic location places it in the gallbladder. Notice the alternating rings of calcified and noncalcified material that form as the stone moves about in the gallbladder lumen.

There is a small calcification (solid black arrow) that overlies the shadow of the left kidney (solid white arrow) on this close-up of a conventional abdominal radiograph. Although the stone is too small to recognize lamination, its location suggests a renal calculus. Because of its greater sensitivity, a CT stone search has essentially replaced conventional radiography for the identification of renal and ureteral calculi.

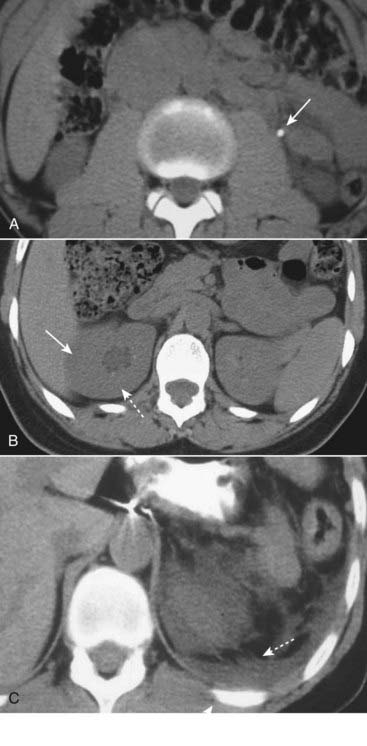

Figure 16-8 Imaging findings of ureteral calculi, three different patients.

A, A calcified stone is seen in the left ureter (solid white arrow). B, Hydronephrosis is present on the right (dotted white arrow) with overall enlargement of the right kidney (solid white arrow). C, There is considerable perinephric stranding (dotted white arrows) and fluid that has leaked from the kidney (solid white arrow), most likely from a rupture of one of the renal fornices.

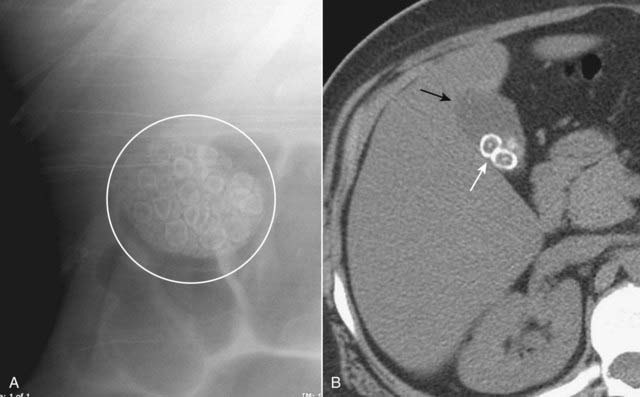

Figure 16-9 Gallstones, conventional radiograph (A) and axial CT scan (B).

A, There are multiple laminated calcifications (white circle) that have interlocking edges, suggesting that they all formed in a hollow viscus in proximity to each other. These are called faceted stones for their characteristic shapes. B, A close-up view of an unenhanced axial CT scan of the right upper quadrant shows several gallstones (solid white arrow), two of which clearly have a central nidus surrounded by laminated, concentric rings of noncalcified and calcified material. The gallbladder (solid black arrow) contains bile fats and is less dense than the liver.

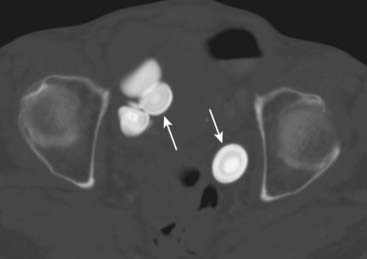

Figure 16-10 Urinary bladder stones.

There are laminated calcifications (solid white arrows) seen on this axial CT scan through the level of the pelvis and windowed to show the laminations better. The laminations imply that these calcifications have formed inside of a hollow viscus. The anatomic location of these calculi places them in the urinary bladder.

TABLE 16-3 LAMINAR OR LAMELLATED CALCIFICATIONS

| Organ of Origin | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Kidney | Most calcified renal stones are composed of calcium oxalate crystals; mostly form due to stasis or infection. |

| Gallbladder | Most calcified gallstones are calcium bilirubinate; they form due to chronic infection and stasis. |

| Urinary bladder | Most bladder calculi contain urate crystals; they form most often from outlet obstruction. |

Cloudlike, Amorphous, Or Popcorn Calcification

Cloudlike, amorphous, or popcorn calcification is calcification that has formed inside of a solid organ or tumor. Examples include:

Cloudlike, amorphous, or popcorn calcification is calcification that has formed inside of a solid organ or tumor. Examples include:

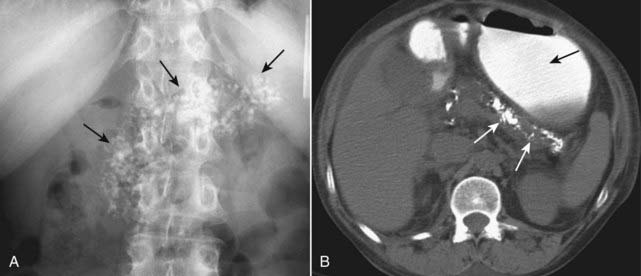

Figure 16-11 Chronic calcific pancreatitis, conventional radiograph (A) and axial CT scan (B).

A, A close-up view of the left upper quadrant of a conventional radiograph of the abdomen shows amorphous calcifications (solid black arrows) implying calcification in a solid organ or tumor. The anatomic distribution of the calcification corresponds to the pancreas. B, In another patient, a nonenhanced image of the upper abdomen shows calcifications distributed along the course of the body and tail of the pancreas (solid white arrows). There is oral contrast seen in the stomach (solid black arrow). These calcifications are pathognomonic of chronic pancreatitis, a chronic and irreversible disease that leads to atrophy of the gland and diabetes, occurring mostly secondary to alcoholism.

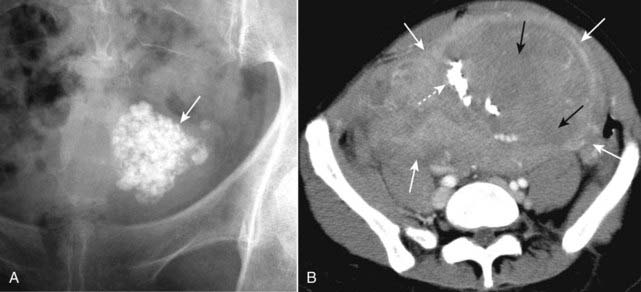

Figure 16-12 Calcified uterine leiomyoma (fibroid) on conventional radiograph (A) and CT (B).

A, There is an amorphous (or popcorn, if you’re hungry) calcification (solid white arrow) visible in the pelvis of this 48-year-old female. The type of calcification suggests formation in a solid organ or tumor. This is the anatomic location and the classical appearance of calcified uterine leiomyomas (fibroids). B, Another patient has large uterine fibroids (solid white arrows), portions of which have necrosed (solid black arrows) and calcified (dotted white arrow). Ultrasound is the study of choice in diagnosing uterine fibroids.

![]() Pitfall: Solid masses that have rimlike calcification

Pitfall: Solid masses that have rimlike calcification

Table 16-5 summarizes the key findings of the four patterns of abnormal calcification.

Table 16-5 summarizes the key findings of the four patterns of abnormal calcification.

Figure 16-13 Calcified rim in uterine leiomyoma.

This is a rimlike calcification in the pelvis of a female patient (solid black arrows), so that it would be appropriate to consider that this calcification formed in the wall of a hollow viscus or saccular structure. In fact, this is a characteristic pattern of calcification in the outer wall of a degenerated uterine leiomyoma (fibroid). Cystic lesions of the ovary might produce this appearance, and ultrasound of the pelvis would be the study of choice to identify the organ of origin.

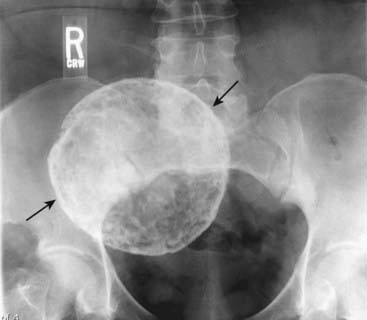

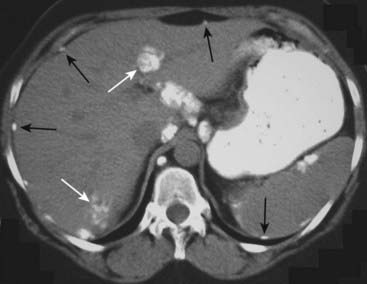

Figure 16-14 Calcified ovarian metastases.

An unenhanced axial CT scan of the upper abdomen shows multiple amorphous calcifications, some within the liver (solid white arrows) and others that stud the peritoneal surface of the abdomen (solid black arrows). This patient had a mucin-producing adenocarcinoma of the ovary that metastasized to the peritoneum and liver. Mucin-producing tumors of the stomach and colon can also produce calcified metastases, but ovarian malignancy would be the most common to metastasize to the peritoneum.

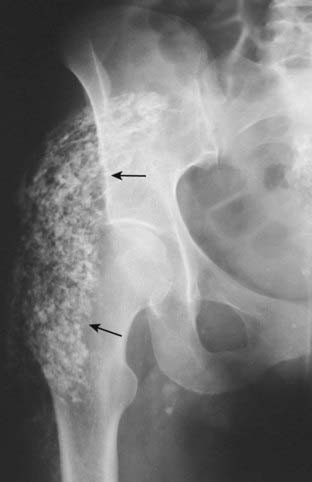

Figure 16-15 Dystrophic calcification in a calcified hematoma.

There are amorphous calcifications demonstrated in the soft tissues overlying the right hip (solid black arrows) suggesting these calcifications have formed within a solid structure. The patient had a history of prior trauma to this region. Heterotopic ossification, which would have a similar appearance, also can form in soft tissues following trauma but it usually is more organized with distinct cortices and trabeculae.

TABLE 16-4 AMORPHOUS, CLOUDLIKE, OR POPCORN CALCIFICATIONS

| Organ of Origin | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Pancreas | Chronic pancreatitis, frequently secondary to alcoholism |

| Uterine fibroids (leiomyomas) | Degenerating fibroids calcify |

| Mucin-producing tumors | Mucin-producing tumors of the ovary, stomach, or colon may calcify as can their metastases |

| Meningioma | Benign, extraaxial brain tumor of older individuals that calcifies about 20% of the time |

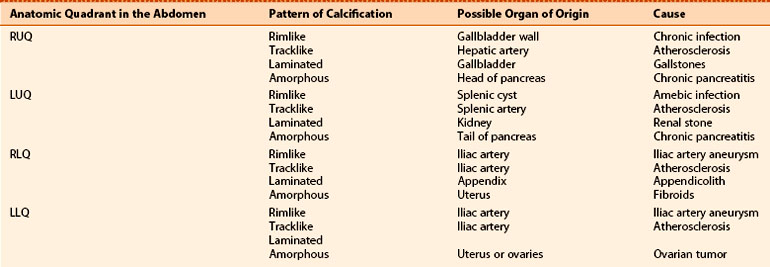

TABLE 16-5 IDENTIFYING THE FOUR TYPES OF ABNORMAL CALCIFICATIONS

| Type of Calcification | Implies | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Rimlike | Formed in wall of hollow viscus | Cysts, aneurysms, gallbladder |

| Linear or tracklike | Formed in walls of tubular structures | Ureters, arteries |

| Lamellar or laminar | Formed in stones | Renal, gallbladder, and bladder calculi |

| Amorphous, cloudlike, popcorn | Forms in a solid organ or tumor | Uterine fibroids, some mucin-producing tumors |

![]() No matter what its cause, the presence of calcification implies a process that is subacute or chronic.

No matter what its cause, the presence of calcification implies a process that is subacute or chronic.

Location Of Calcification

Identifying the pattern of calcification helps in identifying the type of structure in which it has formed.

Identifying the pattern of calcification helps in identifying the type of structure in which it has formed. Weblink

Weblink

Registered users may obtain more information on Recognizing Abnormal Calcifications and Their Causes on StudentConsult.com.

![]() Take-Home Points

Take-Home Points

Recognizing Abnormal Calcifications and Their Causes

Calcifications can be characterized by the pattern of their calcification and their anatomic location.

Four distinct patterns of calcifications are rimlike, linear or tracklike, lamellar (or laminar), and cloudlike (amorphous or popcorn).

Rimlike calcifications imply calcification that has occurred in the wall of a hollow viscus.

Examples of rimlike calcifications include cysts, aneurysms, or saccular organs such as the gallbladder.

Linear or tracklike calcifications imply calcification that has occurred in the walls of tubular structures.

Examples of tracklike calcifications include the walls of arteries and tubular structures such as the ureters, Fallopian tubes, and vas deferens.

Lamellar (or laminar) calcifications imply calcification that forms around a nidus inside a hollow lumen.

Examples of lamellar calcifications include renal calculi, gallstones, and bladder stones.

Cloudlike, amorphous, or popcorn calcification is calcification that has formed inside of a solid organ or tumor.

Examples of amorphous or popcorn calcifications include calcifications in the pancreas, leiomyomas of the uterus, lymph nodes, mucin-producing adenocarcinomas, and dystrophic, soft-tissue calcifications.

Combining the type of calcification with its anatomic location should provide the key to the etiology of most pathologic calcifications. CT scans are especially useful in identifying the type and location of abnormal calcifications.