Chapter 22 Recognizing Fractures and Dislocations

Recognizing an Acute Fracture

Everyone, it seems, is fascinated by a broken bone or two. Fractures are a favorite among those learning radiology, perhaps because of how common they are. Fractures due to moderate trauma are much more common than those due to severe trauma or pathologic fractures.

Everyone, it seems, is fascinated by a broken bone or two. Fractures are a favorite among those learning radiology, perhaps because of how common they are. Fractures due to moderate trauma are much more common than those due to severe trauma or pathologic fractures. A fracture is described as a disruption in the continuity of all or part of the cortex of a bone.

A fracture is described as a disruption in the continuity of all or part of the cortex of a bone.

Figure 22-1 Greenstick and torus fractures.

Incomplete fractures are those that involve only a portion of the cortex. They tend to occur in bones that are “softer” than normal, such as those in children or in adults with bone-softening diseases, such as osteomalacia or Paget disease. There is a greenstick fracture of the distal radius (A), which involves only one part of (dotted white arrow), but not the entire, cortex (solid white arrow). B, In this torus fracture (buckle fracture) of the distal radius, buckling of the cortex is seen (solid black arrows).

![]() Radiologic features of acute fractures (Box 22-1)

Radiologic features of acute fractures (Box 22-1)

Figure 22-2 Nutrient canal versus fracture.

Fracture lines, when viewed in the correct orientation, tend to be “blacker” (more lucent) than other lines normally found in bones, such as nutrient canals. This is a nutrient canal (A) (solid white arrows) while a true fracture is seen in another patient in (B) (dotted black arrows). Notice how the nutrient canal has a sclerotic (whiter) margin, which is not the case with fracture lines. The edges of a fracture tend to be jagged and rough.

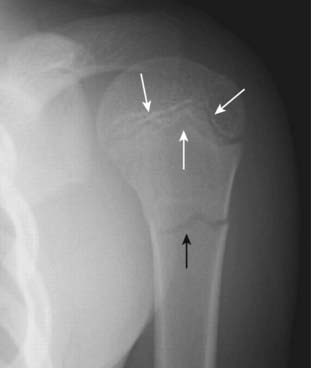

Figure 22-3 Fracture versus epiphyseal plate.

Fracture lines (solid black arrow) tend to be straighter in their course and more acute in their angulation than any naturally occurring lines, such as the epiphyseal plate in the proximal humerus (solid white arrows). Because the top of the metaphysis has irregular hills and valleys, the epiphyseal plate has an undulating course that will allow you to see it in tangent both on the anterior and posterior margins of the humeral head. This gives the mistaken appearance that there is more than one epiphyseal plate.

![]() Pitfalls: sesamoids, accessory ossicles, and unhealed fractures (Table 22-1)

Pitfalls: sesamoids, accessory ossicles, and unhealed fractures (Table 22-1)

TABLE 22-1 DIFFERENTIATING FRACTURES, OSSICLES, AND SESAMOIDS

| Finding | Acute Fracture | Sesamoids and Accessory Ossicles* |

|---|---|---|

| Abrupt disruption of cortex | Yes | No |

| Bilaterally symmetrical | Almost never | Almost always |

| “Fracture line” | Unsharp, jagged | Smooth |

| Bony fragment has a cortex completely around it | No | Yes |

* Old, unhealed fractures will not be bilaterally symmetrical.

Figure 22-4 Pitfalls in fracture diagnosis.

A, Old, unhealed fracture fragments (solid white arrow). B, Sesamoids are bones that form in a tendon as it passes over a joint (solid white arrows). C, Accessory ossicles are accessory epiphyseal or apophyseal ossification centers that do not fuse with the parent bone, (like this os trigonum, open white arrow). Unlike fractures, these small bones are corticated (i.e., there is a white line that completely surrounds the bony fragment) and their edges are usually smooth. Sesamoids and accessory ossicles are usually bilaterally symmetrical.

Recognizing Dislocations and Subluxations

In a dislocation, the bones that originally formed the two components of a joint are no longer in apposition to each other. Dislocations occur only at joints (Fig. 22-5A).

In a dislocation, the bones that originally formed the two components of a joint are no longer in apposition to each other. Dislocations occur only at joints (Fig. 22-5A). In a subluxation, the bones that originally formed the two components of a joint are in partial contact with each other. Subluxations also occur only at joints (Fig. 22-5B).

In a subluxation, the bones that originally formed the two components of a joint are in partial contact with each other. Subluxations also occur only at joints (Fig. 22-5B).

Figure 22-5 Dislocation and subluxation.

A, In a dislocation, the bones that originally formed the two components of a joint are no longer in apposition to each other (solid white arrows). The terminal phalanx is dislocated lateral compared to the middle phalanx. B, In a subluxation, the bones that originally formed the two components of a joint are in partial contact with each other. The humeral head (H) is subluxed inferiorly (solid white arrow) in the glenoid (G) because of large hematoma in the joint secondary to a fracture of the humeral neck (solid black arrow). The hematoma itself is not visible by conventional radiography.

TABLE 22-2 DISLOCATIONS OF THE SHOULDER AND HIP

| Shoulder | Hip |

|---|---|

| Anterior, subcoracoid most common | Posterior and superior more common |

| Caused by a combination of abduction, external rotation, and extension | Frequently caused by knee striking dashboard transmitting force to hip |

| Associated with fractures of humeral head (Hill-Sachs lesion) and glenoid (Bankart lesion) | Associated with fractures of posterior rim of the acetabulum |

Describing Fractures

There is a common lexicon used in describing fractures to facilitate a reproducible description and to assure reliable and accurate communication.

There is a common lexicon used in describing fractures to facilitate a reproducible description and to assure reliable and accurate communication.TABLE 22-3 HOW FRACTURES ARE DESCRIBED

| Parameter | Terms Used |

|---|---|

| Number of fracture fragments | Simple or comminuted |

| Direction of fracture line | Transverse, oblique (diagonal), spiral |

| Relationship of one fragment to another | Displacement, angulation, shortening, and rotation |

| Open to the atmosphere (outside) | Closed or open (compound) |

How Fractures are Described: by the Number of Fracture Fragments

If the fracture produces more than two fragments, it is called a comminuted fracture. Some comminuted fractures have special names.

If the fracture produces more than two fragments, it is called a comminuted fracture. Some comminuted fractures have special names.

Figure 22-6 Segmental fracture and butterfly fractures.

These are two comminuted fractures. A, This is a segmental fracture in which a portion of the shaft exists as an isolated fragment. Notice how the fibula has a center segment (S) and two additional fragments, one on either side (solid white arrows). B, A butterfly fragment is a comminuted fracture in which the central fragment has a triangular shape (dotted white arrow).

How Fractures are Described: by the Direction of the Fracture Line (Table 22-4)

In a transverse fracture, the fracture line is perpendicular to the long axis of the bone. Transverse fractures are caused by a force directed perpendicular to shaft (Fig. 22-7A).

In a transverse fracture, the fracture line is perpendicular to the long axis of the bone. Transverse fractures are caused by a force directed perpendicular to shaft (Fig. 22-7A). In a diagonal or oblique fracture, the fracture line is diagonal in orientation relative to the long axis of the bone. Diagonal or oblique fractures are caused by a force usually applied along the same direction as the long axis of the affected bone (Fig. 22-7B).

In a diagonal or oblique fracture, the fracture line is diagonal in orientation relative to the long axis of the bone. Diagonal or oblique fractures are caused by a force usually applied along the same direction as the long axis of the affected bone (Fig. 22-7B). With a spiral fracture, a twisting force or torque produces a fracture like those that might be caused by planting the foot in a hole while running. Spiral fractures are usually unstable and often associated with soft tissue injuries such as tears in ligaments or tendons (Fig. 22-7C).

With a spiral fracture, a twisting force or torque produces a fracture like those that might be caused by planting the foot in a hole while running. Spiral fractures are usually unstable and often associated with soft tissue injuries such as tears in ligaments or tendons (Fig. 22-7C).TABLE 22-4 DIRECTION OF FRACTURE LINE AND MECHANISM OF INJURY

| Direction of Fracture Line | Mechanism |

|---|---|

| Transverse | Force applied perpendicular to long axis of bone; fracture occurs at point of impact |

| Diagonal (also known as oblique) | Force applied along the long axis of bone; fracture occurs somewhere along shaft |

| Spiral | Twisting or torque injury |

Figure 22-7 Transverse, diagonal, and spiral fracture lines.

A, In a transverse fracture (solid white arrow), the fracture line is perpendicular to the long axis of the bone. B, Diagonal or oblique fractures (solid black arrow) are diagonal in orientation relative to the normal axis of the bone. C, Spiral fractures (solid white arrows) are usually caused by twisting or torque injuries.

How Fractures are Described: by the Relationship of One Fracture Fragment to Another

![]() By convention, abnormalities of the position of bone fragments secondary to fractures describe the relationship of the distal fracture fragment relative to the proximal fragment. These descriptions are based on the position the distal fragment would have normally assumed had the bone not been fractured.

By convention, abnormalities of the position of bone fragments secondary to fractures describe the relationship of the distal fracture fragment relative to the proximal fragment. These descriptions are based on the position the distal fragment would have normally assumed had the bone not been fractured.

There are four major parameters most commonly used to describe the relationship of fracture fragments. Most fractures display more than one of these abnormalities of position. The four parameters are:

There are four major parameters most commonly used to describe the relationship of fracture fragments. Most fractures display more than one of these abnormalities of position. The four parameters are:

Displacement describes the amount by which the distal fragment is offset, front to back and side to side, from the proximal fragment. Displacement is most often described either in terms of percent (the distal fragment is displaced by 50% of the width of the shaft) or by fractions (the distal fragment is displaced half the width of the shaft of the proximal fragment) (Fig. 22-8A).

Displacement describes the amount by which the distal fragment is offset, front to back and side to side, from the proximal fragment. Displacement is most often described either in terms of percent (the distal fragment is displaced by 50% of the width of the shaft) or by fractions (the distal fragment is displaced half the width of the shaft of the proximal fragment) (Fig. 22-8A). Angulation describes the angle between the distal and proximal fragments as a function of the degree to which the distal fragment is deviated from the position it would have assumed were it in its normal position. Angulation is described in degrees and by position (the distal fragment is angulated 15° anteriorly relative to the proximal fragment) (Fig. 22-8B).

Angulation describes the angle between the distal and proximal fragments as a function of the degree to which the distal fragment is deviated from the position it would have assumed were it in its normal position. Angulation is described in degrees and by position (the distal fragment is angulated 15° anteriorly relative to the proximal fragment) (Fig. 22-8B). Shortening describes how much, if any, overlap there is of the ends of the fracture fragments, which translates into how much shorter the fractured bone is than it would be had it not been fractured (Fig. 22-8C).

Shortening describes how much, if any, overlap there is of the ends of the fracture fragments, which translates into how much shorter the fractured bone is than it would be had it not been fractured (Fig. 22-8C).

Rotation is an unusual abnormality in fracture positioning almost always involving the long bones, such as the femur or humerus. Rotation describes the orientation of the joint at one end of the fractured bone relative to the orientation of the joint at the other end of the same bone.

Rotation is an unusual abnormality in fracture positioning almost always involving the long bones, such as the femur or humerus. Rotation describes the orientation of the joint at one end of the fractured bone relative to the orientation of the joint at the other end of the same bone.

Figure 22-8 Fracture parameters.

The orientation of fracture fragments is described by using these four parameters. A, Displacement describes the amount by which the distal fragment (solid white arrow) is offset, front to back and side to side, from the proximal fragment (solid black arrow). B, Angulation describes the angle between the distal and proximal fragments (dotted black line) as a function of the degree to which the distal fragment is deviated from its normal position (solid white line). C, Shortening describes how much, if any, overlap occurs at the ends of the fracture fragments (solid white and black arrows). D, The term that is opposite from shortening is distraction, which refers to the distance the bone fragments are separated from each other (two white arrows show pull of tendons on fracture fragments of patella, black arrow points to distraction of fracture).

An unusual abnormality in fracture positioning, almost always involving the long bones, which describes the orientation of the joint at one end of the fractured bone relative to the orientation of the joint at the other end of the fractured bone. To appreciate rotation, both the joint above and the joint below a fracture must be included, preferably on the same radiograph. In this patient, the proximal tibia (solid black arrow) is oriented in the frontal projection while the distal tibia and ankle (solid white arrow) are rotated and oriented laterally.

How Fractures are Described: by the Relationship of the Fracture to the Atmosphere

A closed fracture is the more common type of fracture in which there is no communication between the fracture fragments and the outside atmosphere.

A closed fracture is the more common type of fracture in which there is no communication between the fracture fragments and the outside atmosphere. In an open or compound fracture, there is communication between the fracture and the outside atmosphere, i.e., a fracture fragment penetrates the skin (Fig. 22-10). Compound fractures have implications regarding the way in which they are treated in order to avoid the complication of osteomyelitis. Whether a fracture is open or not is best diagnosed clinically.

In an open or compound fracture, there is communication between the fracture and the outside atmosphere, i.e., a fracture fragment penetrates the skin (Fig. 22-10). Compound fractures have implications regarding the way in which they are treated in order to avoid the complication of osteomyelitis. Whether a fracture is open or not is best diagnosed clinically.

Figure 22-10 Open (compound) fracture, 5th metacarpal.

Most fractures are closed, meaning there is no communication between the fracture fragments and the outside atmosphere. Open or compound fractures (solid black arrows) have communication between the fracture and the outside (solid white arrow). Whether a fracture is open or not is best evaluated clinically. Treatment of a compound fracture must consider the higher incidence of infection that can occur in these injuries.

Avulsion Fractures

Avulsion is a common mechanism of fracture production in which the fracture fragment (avulsed fragment) is pulled from its parent bone by contraction of a tendon or ligament.

Avulsion is a common mechanism of fracture production in which the fracture fragment (avulsed fragment) is pulled from its parent bone by contraction of a tendon or ligament. Although avulsion fractures can and do occur at any age, they are particularly common in younger individuals engaging in athletic endeavors—in fact, they derive many of their names from the type of athletic activity that produces them, e.g., dancer’s fracture, skier’s fracture, and sprinter’s fracture.

Although avulsion fractures can and do occur at any age, they are particularly common in younger individuals engaging in athletic endeavors—in fact, they derive many of their names from the type of athletic activity that produces them, e.g., dancer’s fracture, skier’s fracture, and sprinter’s fracture. They occur in anatomically predictable locations because tendons insert on bones in a known location (Table 22-5) and the avulsed fragment is typically small (Fig. 22-11).

They occur in anatomically predictable locations because tendons insert on bones in a known location (Table 22-5) and the avulsed fragment is typically small (Fig. 22-11). They sometimes heal with such exuberant callus formation that they can be mistaken for a bone tumor (Fig. 22-12).

They sometimes heal with such exuberant callus formation that they can be mistaken for a bone tumor (Fig. 22-12).TABLE 22-5 AVULSION FRACTURES AROUND THE PELVIS

| Avulsed Fragment | Muscle that Inserts on that Fragment |

|---|---|

| Anterior, superior iliac spine | Sartorius muscle |

| Anterior, inferior iliac spine | Rectus femoris muscle |

| Ischial tuberosity | Hamstring muscles |

| Lesser trochanter of femur | Iliopsoas muscle |

Figure 22-11 Avulsion fractures, ASIS and lesser trochanter.

Avulsion fractures are common fractures in which the avulsed fragment is pulled from its parent bone by contraction of a tendon or ligament. Although avulsion fractures can occur at any age, they are particularly common in younger individuals who engage in athletic endeavors. There is an avulsion of the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) (solid white arrow), which is the site of the insertion of the sartorius muscle. There is also an avulsion of a portion of the lesser trochanter, on which the iliopsoas muscle inserts (dotted white arrow). The patient had participated in track and field events a week prior to this radiograph.

Figure 22-12 Healing avulsion fracture of ischial tuberosity.

Avulsion fractures of the pelvis occur in anatomically predictable locations (tendons insert on bones in known locations) and they are typically small fragments. Sometimes they heal with such exuberant callus formation that they can be mistaken for a bone tumor. This is a healing fracture (solid black arrows) of the ischial tuberosity originally caused by contraction of the hamstring muscles. There is a great deal of external callus present (solid white arrow).

Salter-Harris Fractures: Epiphyseal Plate Fractures in Children

In growing bone, the hypertrophic zone in the growth plate (epiphyseal plate or physis) is most vulnerable to shearing injuries. Epiphyseal plate fractures are common and account for as many as 30% of childhood fractures. By definition, since these are all fractures through an open epiphyseal plate, they can only occur in children.

In growing bone, the hypertrophic zone in the growth plate (epiphyseal plate or physis) is most vulnerable to shearing injuries. Epiphyseal plate fractures are common and account for as many as 30% of childhood fractures. By definition, since these are all fractures through an open epiphyseal plate, they can only occur in children. The Salter-Harris classification of epiphyseal plate injuries is a commonly used method of describing such injuries that helps identify the type of treatment required and predicts the likelihood of complications based on the type of fracture (Fig. 22-13; Table 22-6).

The Salter-Harris classification of epiphyseal plate injuries is a commonly used method of describing such injuries that helps identify the type of treatment required and predicts the likelihood of complications based on the type of fracture (Fig. 22-13; Table 22-6).

Figure 22-13 The Salter-Harris classification of epiphyseal plate fractures helps in recognizing the likelihood of complications based on the type of fracture.

All of these fractures involve the epiphyseal plate (growth plate). Type I are fractures of the epiphyseal plate alone. Type II fractures, the most common of the epiphyseal plate fractures, involve the epiphyseal plate and metaphysis. These first two types have a favorable prognosis. Type III are fractures of the epiphyseal plate and the epiphysis and have a less favorable prognosis. Type IV is a fracture of the epiphyseal plate, epiphysis, and metaphysis. It has an even less favorable prognosis. Type V is a crush injury of the epiphyseal plate. It has the worst prognosis.

(Adapted from Robertson J, Shilkofski N, editors: The Johns Hopkins Hospital: The Harriet Lane Handbook, ed 17, Philadelphia, 2005, Mosby.)

TABLE 22-6 SALTER-HARRIS CLASSIFICATION OF EPIPHYSEAL PLATE FRACTURES

| Type | What’s Fractured | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| I | Epiphyseal plate | Seen in phalanges, distal radius, SCFE; good prognosis |

| II | Epiphyseal plate and metaphysis | Most common of all Salter-Harris fractures; frequently distal radius; displays corner sign; good prognosis |

| III | Epiphyseal plate and epiphysis | Intraarticular fracture; frequently distal tibia; prognosis is less favorable |

| IV | Epiphyseal plate, epiphysis, and metaphysis | Seen in distal humerus and distal tibia; poor prognosis |

| V | Crush injury of epiphyseal plate | Worst prognosis; difficult to diagnose until healing begins |

Type I: Fractures of the epiphyseal plate alone

Type I: Fractures of the epiphyseal plate alone

Type II: Fracture of the epiphyseal plate and fracture of the metaphysis

Type II: Fracture of the epiphyseal plate and fracture of the metaphysis

Type III: Fracture of the epiphyseal plate and the epiphysis

Type III: Fracture of the epiphyseal plate and the epiphysis

Type IV: Fracture of the epiphyseal plate, metaphysis, and epiphysis

Type IV: Fracture of the epiphyseal plate, metaphysis, and epiphysis

Type V: Crush fracture of epiphyseal plate

Type V: Crush fracture of epiphyseal plate

Figure 22-14 Slipped capital femoral epiphysis.

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) is a manifestation of a Salter-Harris type I injury. It occurs more often in taller and heavier teenage boys and produces inferior, medial, and posterior slippage of the proximal femoral epiphysis (solid black arrow) relative to the neck of the femur. A line drawn parallel to the neck of the femur (solid white lines) should intersect a portion of the head. It does so on the normal left side, but does not on the right side because the epiphysis has slipped.

Figure 22-15 Salter-Harris II fracture.

In type II fractures, there is a fracture of the epiphyseal plate and a fracture of the metaphysis. This is the most common type of Salter-Harris fracture. The small metaphyseal fracture fragment (solid white arrow) produces the so-called corner sign.

Figure 22-16 Salter-Harris III fracture.

With type III fractures, a fracture of the epiphyseal plate as well as a longitudinal fracture through the epiphysis itself is seen (solid white arrow), which means the fracture invariably enters the joint space and fractures the articular cartilage. This can have long-term implications for the development of secondary osteoarthritis and can result in asymmetric and premature fusion of the growth plate with subsequent deformity of the bone.

Figure 22-17 Salter-Harris IV fracture.

In type IV fractures, a fracture of the epiphyseal plate, metaphysis (solid white arrow), and the epiphysis (solid black arrow) is present. These have a poorer prognosis than other Salter-Harris fractures because of increased likelihood of premature and possibly asymmetric closure of the epiphyseal plate. Salter-Harris IV fractures are most often seen in the distal humerus and distal tibia.

Figure 22-18 Salter-Harris V fracture.

Type V fractures are crush fractures of the epiphyseal plate. They are frequently not diagnosed until after they produce their growth impairment through early focal fusion of the growth plate leading to angular deformity. In this child, the medial portion of the distal radial epiphyseal plate has fused (solid black arrow) while the lateral portion remains open (dotted black arrow). This premature fusion of the medial growth plate has resulted in an angular deformity of the distal radius (black line).

Child Abuse

Salter-Harris fractures are examples of accidental injuries in children. Certain kinds of fractures at other sites or of other types can be highly suggestive for nonaccidental injuries produced by abuse. Radiologic evaluations are key in diagnosing child abuse.

Salter-Harris fractures are examples of accidental injuries in children. Certain kinds of fractures at other sites or of other types can be highly suggestive for nonaccidental injuries produced by abuse. Radiologic evaluations are key in diagnosing child abuse.

![]() There are several fracture sites and characteristics that should raise the suspicion for child abuse (Table 22-7).

There are several fracture sites and characteristics that should raise the suspicion for child abuse (Table 22-7).

TABLE 22-7 SKELETAL TRAUMA SUSPICIOUS FOR CHILD ABUSE

| Site(s) | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Distal femur, distal humerus, wrist, ankle | Metaphyseal corner fractures |

| Multiple | Fractures in different stages of healing |

| Femur, humerus, tibia | Spiral fractures <1 year of age |

| Posterior ribs, avulsed spinous processes | Unusual “naturally occurring” fractures <5 years of age |

| Multiple skull fractures | Multiple fractures of occipital bone should suggest child abuse |

| Fractures with abundant callous formation | Implies repeated trauma and no immobilization |

| Metacarpal and metatarsal fractures | Unusual “naturally occurring” fractures <5 years of age |

| Sternal and scapular fractures | |

| Vertebral body fractures and subluxations |

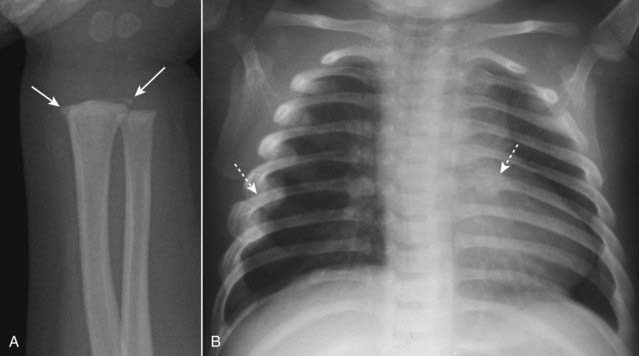

A, There are metaphyseal corner fractures (solid white arrows), small avulsion-type fractures of the distal radius, a finding characteristic of child abuse. B, There are several healing rib fractures (dotted white arrows), including one involving the left 6th posterior rib. Fractures of the posterior ribs are unusual, even in accidental trauma, and should raise suspicion for child abuse.

Stress Fractures

Stress fractures occur as a result of numerous microfractures in which bone is subjected to repeated stretching and compressive forces.

Stress fractures occur as a result of numerous microfractures in which bone is subjected to repeated stretching and compressive forces.

![]() Although conventional radiographs are usually the study first obtained, they may initially appear normal in as many as 85% of cases, so it is common for a patient to complain of pain yet have a normal-appearing radiograph at first.

Although conventional radiographs are usually the study first obtained, they may initially appear normal in as many as 85% of cases, so it is common for a patient to complain of pain yet have a normal-appearing radiograph at first.

The fracture may not be diagnosable until after periosteal new bone formation occurs or, in the case of a healing stress fracture of cancellous bone, the appearance of a thin, dense zone of sclerosis across the medullary cavity (Fig. 22-20).

The fracture may not be diagnosable until after periosteal new bone formation occurs or, in the case of a healing stress fracture of cancellous bone, the appearance of a thin, dense zone of sclerosis across the medullary cavity (Fig. 22-20). Radionuclide bone scans will usually be positive much earlier than conventional radiographs: within 6 to 72 hours after the injury.

Radionuclide bone scans will usually be positive much earlier than conventional radiographs: within 6 to 72 hours after the injury. Some common locations for stress fractures are the shafts of long bones such as the proximal femur or proximal tibia, as well as the calcaneous and the 2nd and 3rd metatarsals (march fractures).

Some common locations for stress fractures are the shafts of long bones such as the proximal femur or proximal tibia, as well as the calcaneous and the 2nd and 3rd metatarsals (march fractures).

Figure 22-20 Stress fracture, two frontal views taken three weeks apart.

A, Although conventional radiographs are the study of first choice, they may initially appear normal in as many as 85% of cases, so it is common for a patient to complain of pain yet have a normal-appearing radiograph, as occurs here one day after pain began. Radionuclide bone scan will usually be positive much earlier than conventional radiographs: within 6 to 72 hours after the injury. B, The fracture may not be diagnosable until after periosteal new bone formation forms (solid white arrow) or, in the case of a healing stress fracture of cancellous bone, the appearance of a thin, dense zone of sclerosis across the medullary cavity (solid black arrow). This radiograph was taken 3 weeks after the first.

Common Fracture Eponyms

There are almost as many fracture eponyms as there are types of fractures. We will concentrate on five of the most commonly used eponyms.

There are almost as many fracture eponyms as there are types of fractures. We will concentrate on five of the most commonly used eponyms. Colles’ fracture is a fracture of the distal radius with dorsal angulation of the distal radial fracture fragment caused by a fall on the outstretched hand (sometimes abbreviated as FOOSH). There is frequently an associated fracture of the ulnar styloid (Fig. 22-21).

Colles’ fracture is a fracture of the distal radius with dorsal angulation of the distal radial fracture fragment caused by a fall on the outstretched hand (sometimes abbreviated as FOOSH). There is frequently an associated fracture of the ulnar styloid (Fig. 22-21). Smith’s fracture is a fracture of the distal radius with palmar angulation of the distal radial fracture fragment (a reverse Colles fracture). It is caused by a fall on the back of the flexed hand (Fig. 22-22).

Smith’s fracture is a fracture of the distal radius with palmar angulation of the distal radial fracture fragment (a reverse Colles fracture). It is caused by a fall on the back of the flexed hand (Fig. 22-22). Jones fracture is a transverse fracture of the 5th metatarsal about 1 to 2 cm from its base caused by plantar flexion of the foot and inversion of the ankle. A Jones fracture may take longer to heal than the more common avulsion fracture of the base of the 5th metatarsal (Fig. 22-23).

Jones fracture is a transverse fracture of the 5th metatarsal about 1 to 2 cm from its base caused by plantar flexion of the foot and inversion of the ankle. A Jones fracture may take longer to heal than the more common avulsion fracture of the base of the 5th metatarsal (Fig. 22-23). Boxer’s fracture is a fracture of the head of the 5th metacarpal (little finger) with palmar angulation of the distal fracture fragment. It is most often the result of punching a person or wall (Fig. 22-24).

Boxer’s fracture is a fracture of the head of the 5th metacarpal (little finger) with palmar angulation of the distal fracture fragment. It is most often the result of punching a person or wall (Fig. 22-24). March fracture is a type of stress fracture caused by repeated microfractures to the foot from trauma (such as marching), most often affecting the shafts of the 2nd and 3rd metatarsals (see Fig. 22-20).

March fracture is a type of stress fracture caused by repeated microfractures to the foot from trauma (such as marching), most often affecting the shafts of the 2nd and 3rd metatarsals (see Fig. 22-20).

Figure 22-21 Colles’ fracture, frontal (A) and lateral (B) views.

Colles’ fractures are fractures of the distal radius (solid white arrows) with dorsal angulation of the distal radial fracture fragments (solid black arrow) caused by a fall on the outstretched hand (sometimes abbreviated as FOOSH). There is frequently an associated fracture of the ulnar styloid (dotted white arrow).

Figure 22-22 Smith’s fracture.

A Smith fracture is a fracture of the distal radius (solid white arrow) with palmar angulation of the distal radial fracture fragment (solid black arrow), the reverse of a Colles fracture. It is caused by a fall on the back of the flexed hand.

Figure 22-23 Jones fracture, base of 5th metatarsal.

A Jones fracture is a transverse fracture of the base 5th metatarsal (dotted white arrow). It occurs about 1 to 2 cm from the tuberosity of the 5th metatarsal (solid white arrow) and frequently takes longer to heal than an avulsion fracture of the tuberosity. It is caused by plantar flexion of the foot and inversion of the ankle.

Some Easily Missed Fractures or Dislocations

Look at these areas carefully when evaluating for a possible fracture; then look a second and third time.

Look at these areas carefully when evaluating for a possible fracture; then look a second and third time. Scaphoid fractures (common)

Scaphoid fractures (common)

Buckle fractures of radius and ulna in children (common)

Buckle fractures of radius and ulna in children (common)

Radial head fracture (common)

Radial head fracture (common)

Supracondylar fracture of the distal humerus in children (common)

Supracondylar fracture of the distal humerus in children (common)

Posterior dislocation of the shoulder (uncommon)

Posterior dislocation of the shoulder (uncommon)

Hip fractures in the elderly (common)

Hip fractures in the elderly (common)

Look for indirect signs indicating the possibility of an underlying fracture (Table 22-8, Fig. 22-31).

Look for indirect signs indicating the possibility of an underlying fracture (Table 22-8, Fig. 22-31).

Figure 22-25 Scaphoid fracture.

Scaphoid fractures are common. They are suspected clinically if there is tenderness in the anatomic snuff box after a fall on an outstretched hand. Look for linear fracture lines on special angled views of the scaphoid (solid white arrow). Fractures across the waist of the scaphoid can lead to avascular necrosis of proximal pole of that bone.

Figure 22-26 Avascular necrosis of the proximal pole of the scaphoid.

A close-up frontal view of the wrist demonstrates that the proximal pole of the scaphoid (solid black arrow) is denser than the distal pole (solid white arrow). There is a fracture through the waist of the scaphoid (dotted white arrow). Because of the peculiar blood supply of the scaphoid (from distal to proximal), fractures through the waist may interrupt the proximal blood supply while the other bones of the wrist, having normal blood supply, become demineralized. This makes the proximal pole of the scaphoid appear denser relative to the other bones of the wrist.

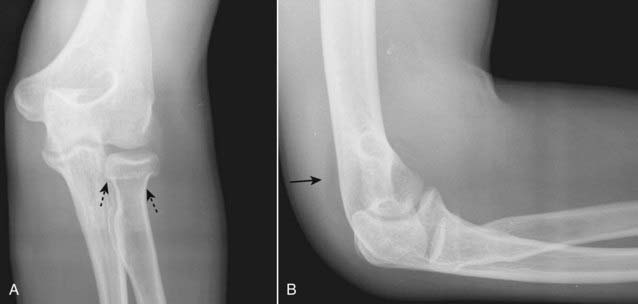

Figure 22-27 Fracture of radial head with joint effusion, frontal (A) and lateral (B) views.

Radial head fractures (dotted black arrows) are the most common fractures of the elbow in an adult. Look for fat appearing as a crescentic lucency along the dorsal aspect of the distal humerus (solid black arrow) caused by intracapsular, extrasynovial fat that is lifted away from the bone by swelling of the joint capsule due to a traumatic hemarthrosis—the positive posterior fat-pad sign. Virtually all studies of bones will include at least two views at 90° angles to each other called orthogonal views. Many protocols call for two additional oblique views which enable you to visualize more of the cortex in profile.

Figure 22-28 Supracondylar fracture.

A supracondylar fracture of the distal humerus is a common fracture in children, and its findings may be subtle. Most of these fractures produce posterior displacement of the capitellum of the distal humerus. On a true lateral film, the anterior humeral line (a line drawn tangential to the anterior humeral cortex and shown here in black) should bisect the middle portion of the capitellum (solid white arrow). When there is a supracondylar fracture, this line will pass more anteriorly, as it does here. There is a positive posterior fat pad sign present (solid black arrow).

Figure 22-29 Posterior dislocation of the shoulder.

Posterior dislocations of the shoulder are much less common than anterior dislocations but more difficult to diagnose. A, On the frontal view, look for the humeral head (H) to be persistently fixed in internal rotation and resemble a “lightbulb” no matter how the patient turns the forearm. There is also an increased distance between the head and the glenoid (solid black arrow). B, On the “Y” view, the head (H) will lie under the acromion (A), a posterior structure of the scapula. The coracoid process (C) is anterior. Normally, the head is centered between the coracoid and the acromion in the glenoid fossa (G).

Figure 22-30 Impacted subcapital hip fracture.

Hip fractures are relatively common fractures in the elderly and are frequently related to osteoporosis. Look for angulation of the cortex (solid white arrow) and zones of increased density (solid black arrows) indicating impaction. Conventional radiographs of the femoral neck should be obtained with the patient’s leg in internal rotation (as shown here) so as to display the neck in profile. Hip fractures can be very subtle and sometimes require additional imaging such as MRI or bone scan for their diagnosis.

TABLE 22-8 INDIRECT SIGNS OF POSSIBLE FRACTURE

| Sign | Remarks |

|---|---|

| Soft tissue swelling | Frequently accompanies a fracture but does not necessarily mean that a fracture is present |

| Disappearance of normal fat stripes | The pronator quadratus fat stripe on the volar aspect of the wrist, for example, may be displaced with a fracture of the distal radius (see Fig. 22-31). |

| Joint effusion | The positive posterior fat pad sign seen on the dorsal aspect of the distal humerus from a traumatic joint effusion is an example (see Fig. 22-27B). |

| Periosteal reaction | Sometimes the healing of a fracture will be the first manifestation that a fracture was present, especially with stress fractures of the foot. |

Figure 22-31 Normal and abnormal pronator quadratus fat plane.

Soft tissue abnormalities can provide clues to the presence of subtle fractures or help confirm the significance of a questionable finding. Here is an example of a normal fascial plane (A) produced by the pronator quadratus (solid white arrow points to lucency) on the volar aspect of the wrist compared to the bulging fascial plane (dotted white arrow), which has occurred because of soft tissue swelling accompanying a fracture of the distal radius (solid black arrow) in (B).

Fracture Healing

Fracture healing is determined by many factors including the age of the patient, the fracture site, the position of the fracture fragments, the degree of immobilization, and the blood supply to the fracture site (Table 22-9).

Fracture healing is determined by many factors including the age of the patient, the fracture site, the position of the fracture fragments, the degree of immobilization, and the blood supply to the fracture site (Table 22-9). Over the next several weeks, osteoclasts act to remove the diseased bone. The fracture line may actually minimally widen at this time.

Over the next several weeks, osteoclasts act to remove the diseased bone. The fracture line may actually minimally widen at this time. Then, over the course of several more weeks, new bone (callus) begins to bridge the fracture gap (Fig. 22-32).

Then, over the course of several more weeks, new bone (callus) begins to bridge the fracture gap (Fig. 22-32).

Remodeling of bone begins at about 8 to 12 weeks postfracture as mechanical forces, in part, begin to adjust the bone to its original shape.

Remodeling of bone begins at about 8 to 12 weeks postfracture as mechanical forces, in part, begin to adjust the bone to its original shape.

Complications of the healing process

Complications of the healing process

TABLE 22-9 FACTORS THAT AFFECT FRACTURE HEALING

| Accelerate Fracture Healing | Delay Fracture Healing |

|---|---|

| Youth | Old age |

| Early immobilization | Delayed immobilization |

| Adequate duration of immobilization | Too short a duration of immobilization |

| Good blood supply | Poor blood supply |

| Physical activity after adequate immobilization | Steroids |

| Adequate mineralization | Osteoporosis, osteomalacia |

Figure 22-32 Healing humeral fracture.

Immediately following a fracture, there is hemorrhage into the fracture site. Over the next several weeks, new bone (callus) begins to bridge the fracture gap. Internal endosteal healing is manifest by indistinctness of the fracture line (solid black arrow) eventually leading to obliteration of the fracture line. External, periosteal healing is manifest by external callus formation (solid white arrows) leading to bridging of the fracture site.

Figure 22-33 Nonunion of clavicular fracture.

Nonunion is a radiologic diagnosis that implies fracture healing is not likely to occur because the processes leading to the repair of bone have ceased. It is characterized by smooth and sclerotic fracture margins with distraction of the fracture fragments (solid white arrows). A pseudarthrosis, complete with a synovial lining, may form at the fracture site.

Weblink

Weblink

Registered users may obtain more information on Recognizing Fractures and Dislocations on StudentConsult.com.

![]() Take-Home Points

Take-Home Points

Recognizing Fractures and Dislocations

A fracture is described as a disruption in the continuity of all or part of the cortex of a bone.

Complete fractures involve the entire cortex, are more common, and typically occur in adults; incomplete fractures involve only a part of the cortex and typically occur in bones that are softer, such as those of children; torus and greenstick fractures are incomplete fractures.

Fracture lines tend to be blacker, more sharply angled, and more jagged than other lucencies in bones such as nutrient canals or epiphyseal plates.

Sesamoids, accessory ossicles, and unhealed fractures may mimic acute fractures but all will have smooth and corticated margins.

Dislocation is present when two bones that originally formed a joint are no longer in contact with each other; subluxation is present when two bones that originally formed a joint are in partial contact with each other.

Fractures are described in many ways including the number of fracture fragments, direction of the fracture line, relationship of the fragments to each other, and whether or not they communicate with the outside atmosphere.

Simple fractures have two fragments; comminuted fractures have more than two fragments; segmental and butterfly fractures describe two types of comminuted fracture.

The direction of fracture lines is described as transverse, diagonal, or spiral.

The relationships of the fragments of a fracture are described by four parameters: displacement, angulation, shortening, and rotation.

Closed fractures are those in which there is no communication between the fracture and the outside atmosphere; they are much more common than open or compound fractures in which there is communication with the outside atmosphere.

Avulsion fractures are produced by the forceful contraction of a tendon or ligament; they can occur at any age but are particularly common in younger, athletic individuals.

The Salter-Harris classification categorizes fractures through the epiphyseal plate that are graded by severity and prognosis, the more severe having an increased risk of resulting in angular deformities or shortening of the affected bone.

Child abuse should be suspected when there are multiple fractures in various stages of healing, metaphyseal corner fractures, rib fractures, and skull fractures, especially if multiple.

Stress fractures, such as march fractures in the metatarsals, occur as a result of numerous microfractures and frequently are not visible on conventional radiographs taken when the pain first begins; after some time, bony callus formation or a dense zone of sclerosis becomes visible.

Some common named fractures are Colles’ fracture (of the radius), Smith’s fracture (of the radius), Jones fracture (of the base of the 5th metatarsal), boxer’s fracture (of the head of the 5th metacarpal), and march fracture (in the foot).

Some fractures are more difficult to detect than others; the easily missed fractures (and how common they are) include scaphoid fractures (common), buckle fractures of the radius and ulna (common), radial head fractures (common), supracondylar fractures (common), posterior dislocations of the shoulder (uncommon), and hip fractures (common).

Soft tissue swelling, the disappearance of normal fat stripes and fascial planes, joint effusions, and periosteal reaction are indirect signs that should alert you to the possibility of an underlying fracture.

Fractures heal with a combination of endosteal callus, recognized by a progressive indistinctness of the fracture line, and external callus that bridges the fracture site; many factors affect fracture healing, including the age of the patient, the degree of mobility of the fracture, and its blood supply.

Delayed union refers to a fracture that is taking longer to heal than is usually required for that site; malunion means the fracture is healing but in a mechanically or cosmetically unacceptable way; nonunion is a radiologic diagnosis that implies there is little if any likelihood the fracture will heal.