Chapter 20 Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Understanding the Principles and Recognizing the Basics

How MRI Works

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) involves the use of a very strong magnetic field to manipulate the electromagnetic activity of atomic nuclei in a way that releases energy in the form of radiofrequency signals, which are recorded by the scanner’s receiving coils and then computer-processed to form an image.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) involves the use of a very strong magnetic field to manipulate the electromagnetic activity of atomic nuclei in a way that releases energy in the form of radiofrequency signals, which are recorded by the scanner’s receiving coils and then computer-processed to form an image.

Each proton has a positive electrical charge, and because protons also have a spin, this charge is constantly moving.

Each proton has a positive electrical charge, and because protons also have a spin, this charge is constantly moving.

When a patient enters an MRI scanner, though, the mini-magnet protons all align with the more powerful external magnetic field of the MRI magnet.

When a patient enters an MRI scanner, though, the mini-magnet protons all align with the more powerful external magnetic field of the MRI magnet.

Hardware that Makes Up an MRI Scanner

Main Magnet

Superconducting magnets contain a conducting coil that is cooled down to superconducting temperature in order to carry the current (4° K or −269° Celsius).

Superconducting magnets contain a conducting coil that is cooled down to superconducting temperature in order to carry the current (4° K or −269° Celsius).

![]() At temperatures that low (close to absolute zero), resistance to the flow of electricity in the conductor practically disappears.

At temperatures that low (close to absolute zero), resistance to the flow of electricity in the conductor practically disappears.

Therefore, an electric current sent once through this ultracold conducting material will continuously flow and create a permanent magnetic field. The magnet in an MRI scanner is always “on.”

Therefore, an electric current sent once through this ultracold conducting material will continuously flow and create a permanent magnetic field. The magnet in an MRI scanner is always “on.” If the temperature increases above these superconducting temperatures, a quench occurs, and there is suddenly resistance to flow of electricity. The energy stored in the magnetic coils then becomes converted to heat. A quench can be initiated manually if there is an emergent need to turn off the MRI magnet, but it is extremely expensive to turn the magnet back on after a quench.

If the temperature increases above these superconducting temperatures, a quench occurs, and there is suddenly resistance to flow of electricity. The energy stored in the magnetic coils then becomes converted to heat. A quench can be initiated manually if there is an emergent need to turn off the MRI magnet, but it is extremely expensive to turn the magnet back on after a quench. Most scanners today have a magnetic field strength between 0.5 and 3 Tesla.

Most scanners today have a magnetic field strength between 0.5 and 3 Tesla.

Coils

An important part of the MRI scanner are the coils placed within the magnet. These coils are responsible for either transmitting the radiofrequency (RF) pulses (transmitter coils) that excite the protons, or receiving the signal (or echo) given off by these excited protons (receiver coils).

An important part of the MRI scanner are the coils placed within the magnet. These coils are responsible for either transmitting the radiofrequency (RF) pulses (transmitter coils) that excite the protons, or receiving the signal (or echo) given off by these excited protons (receiver coils). Types of coils

Types of coils

![]() These coils generate additional linear, electromagnetic fields that vary the magnetic field and are important because they help relate the signal to an exact location and tissue, and make slice selection and spatial information possible. These coils are the source of the repetitive, machine-gunlike banging noise characteristic of MRI, and are essential for creating images.

These coils generate additional linear, electromagnetic fields that vary the magnetic field and are important because they help relate the signal to an exact location and tissue, and make slice selection and spatial information possible. These coils are the source of the repetitive, machine-gunlike banging noise characteristic of MRI, and are essential for creating images.

What Happens Once Scanning Begins

When the patient is placed in the scanner magnet, the transmitter coils send a short (measured in milliseconds) electromagnetic pulse called a radiofrequency (RF) pulse.

When the patient is placed in the scanner magnet, the transmitter coils send a short (measured in milliseconds) electromagnetic pulse called a radiofrequency (RF) pulse.

When the RF pulse is turned off, the displaced protons relax and realign with the main magnetic field, and energy subsequently released in the form of radiofrequency signals (the echo) is detected by the receiver coils.

When the RF pulse is turned off, the displaced protons relax and realign with the main magnetic field, and energy subsequently released in the form of radiofrequency signals (the echo) is detected by the receiver coils.

![]() The times it takes for this recovery and decay to occur and the echo to be generated are called T1 and T2.

The times it takes for this recovery and decay to occur and the echo to be generated are called T1 and T2.

T1 and T2 are both time constants, and it is the values of the T1 and T2 relaxation times that allow different tissues to be identified.

T1 and T2 are both time constants, and it is the values of the T1 and T2 relaxation times that allow different tissues to be identified.

T1 relaxation (or recovery) is the time it takes for the tissue to recover to its longitudinal state, the time before the RF pulse was administered.

T1 relaxation (or recovery) is the time it takes for the tissue to recover to its longitudinal state, the time before the RF pulse was administered.Pulse Sequences

Pulse sequences consist of a set of imaging parameters determined in advance by protocols for specific diseases and body parts and then preselected by the MRI technologist at the computer at the time of the study to send a set of instructions to the RF generator and gradient amplifiers.

Pulse sequences consist of a set of imaging parameters determined in advance by protocols for specific diseases and body parts and then preselected by the MRI technologist at the computer at the time of the study to send a set of instructions to the RF generator and gradient amplifiers.

How can You Identify a T1-Weighted or T2-Weighted Image?

Different tissues have different T1 and T2 values (relaxation and recovery time constants), which is why fat, muscle, and bone, for example, will appear differently not only from each other but also with different pulse sequences.

Different tissues have different T1 and T2 values (relaxation and recovery time constants), which is why fat, muscle, and bone, for example, will appear differently not only from each other but also with different pulse sequences.

“Bright” translates into “whiter” or having “increased signal intensity” on MRI scans. “Dark” translates into “blacker” or having “decreased signal intensity” on MRI.

“Bright” translates into “whiter” or having “increased signal intensity” on MRI scans. “Dark” translates into “blacker” or having “decreased signal intensity” on MRI. A key point is that water will be dark on T1-weighted images and bright on T2-weighted images. Water is T1-dark and T2-bright.

A key point is that water will be dark on T1-weighted images and bright on T2-weighted images. Water is T1-dark and T2-bright.

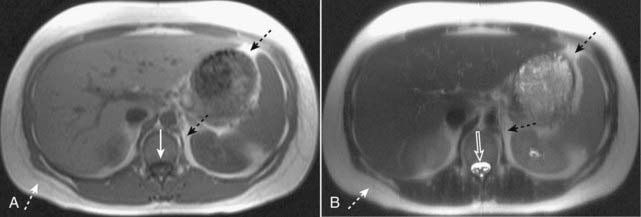

Figure 20-1 Normal T1-weighted and T2-weighted axial images of the abdomen.

Because cerebrospinal fluid is similar to water in density, it appears dark on the T1-weighted image (A) (solid white arrow), and bright on the T2-weighted image (B) (open white arrow). Subcutaneous fat (dotted white arrows) and intraabdominal fat (dotted black arrows) are bright on both T1-weighted and T2-weighted images.

![]() Certain tissues and structures are typically bright on T1-weighted images.

Certain tissues and structures are typically bright on T1-weighted images.

Certain tissues and structures are typically bright on T2-weighted images.

Certain tissues and structures are typically bright on T2-weighted images.

Suppression

Suppression

There are many other pulse sequences besides T1-weighted and T2-weighted images that typically comprise a particular MRI scan protocol, such as diffusion-weighted images (DWI), proton density-weighted images, and an entire alphabet soup of catchy acronyms like STIR andMRA/TOF.

There are many other pulse sequences besides T1-weighted and T2-weighted images that typically comprise a particular MRI scan protocol, such as diffusion-weighted images (DWI), proton density-weighted images, and an entire alphabet soup of catchy acronyms like STIR andMRA/TOF.

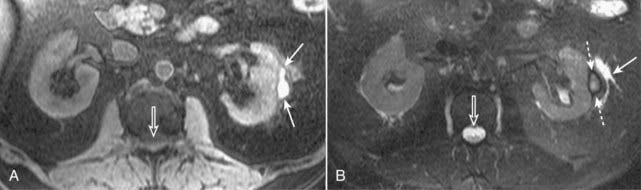

Figure 20-2 Subcapsular hematoma of the kidney.

A, Axial T1-weighted fat-suppressed image demonstrates a bright subcapsular hematoma (solid white arrows) involving the left kidney laterally. We can tell that this is a T1-weighted image because cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the spinal canal is dark (open white arrow). B, Axial T2-weighted, fat-suppressed image again demonstrates a slightly bright left subcapsular hematoma with a dark rim of hemosiderin (dotted white arrows) indicating surrounding older blood. There is a small amount of adjacent left perinephric fluid (solid white arrow). The bright signal of the CSF helps us to recognize this image as a T2-weighted image (open white arrow).

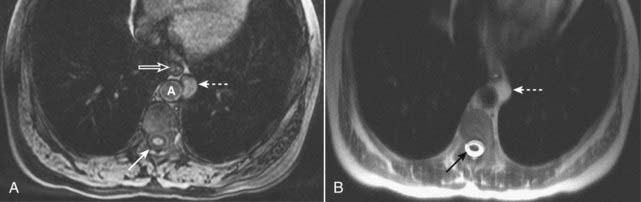

Figure 20-3 Proteinaceous enteric cyst.

A, Axial T1-weighted fat-suppressed image demonstrates a left-sided, mediastinal bright mass (dotted white arrow) adjacent to the esophagus (open white arrow) and aorta (A). Notice that this mass is brighter than the CSF in the spinal canal (solid white arrow). B, Axial T2-weighted image shows that the mass is T2 bright (dotted white arrow), but not as bright as the CSF in the spinal canal (solid black arrow). Contrast-enhanced images (not shown) demonstrated no enhancement. At surgery, this mass was found to represent a benign enteric cyst containing proteinaceous (as opposed to purely simple) fluid.

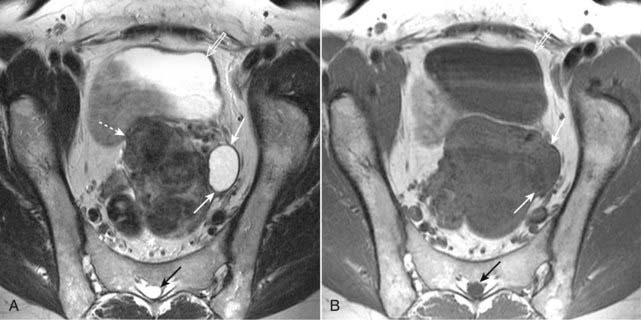

Figure 20-4 Simple left ovarian cyst.

A, Axial T2-weighted image demonstrates an ovoid, homogeneously bright lesion in the left ovary (solid white arrows) adjacent to a fibroid uterus (dotted white arrows). Note that urine in the bladder (open white arrow) and CSF in the spinal canal (solid black arrow) are both bright, which helps us identify this image as a T2-weighted image. B, Axial T1-weighted image shows that this left ovarian lesion is dark (solid white arrows) and therefore consistent with simple fluid. Urine in the bladder (open white arrow) and CSF in the spinal canal (closed black arrow) are also dark.

Figure 20-5 Metastatic melanoma.

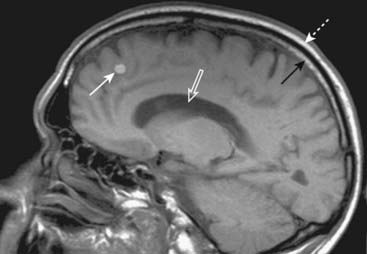

Sagittal T1-weighted image of the brain demonstrates a bright mass (solid white arrow) in the frontal lobe representing metastatic melanoma. Notice that both the yellow bone marrow within the skull (solid black arrow) and the overlying subcutaneous fat (dotted white arrow) are bright. We can tell that this is a T1-weighted image because the CSF in the lateral ventricles is dark (open white arrow).

Figure 20-6 Glioblastoma multiforme with surrounding edema.

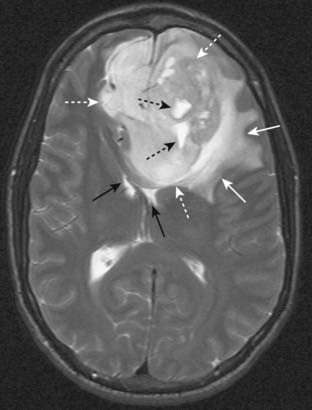

Axial T2-weighted image demonstrates bright vasogenic type edema (solid white arrows) surrounding a large, lobulated frontal lobe mass (dotted white arrows) representing glioblastoma multiforme, an aggressive brain tumor. There are a few bright areas of cystic degeneration (dotted black arrows) within this mass. The frontal horns of the lateral ventricles are compressed (solid black arrows).

Figure 20-7 Bone marrow edema due to transient lateral patellar dislocation.

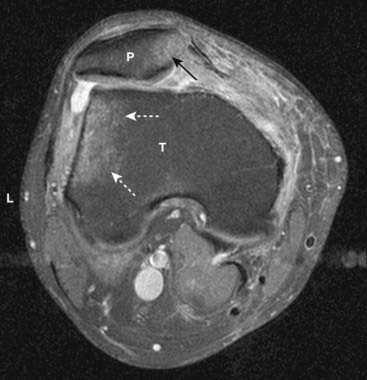

Axial proton-density, fat-saturated image (a T2-like sequence) demonstrates bright bone marrow edema involving the lateral (L) tibial (T) plateau (dotted white arrows) and medial aspect of the patella (P) (solid black arrow). This edema is due to recent lateral patellar dislocation with contusion of the patella as it struck the tibia.

Figure 20-8 Normal T2-weighted fat-suppressed axial image of the abdomen.

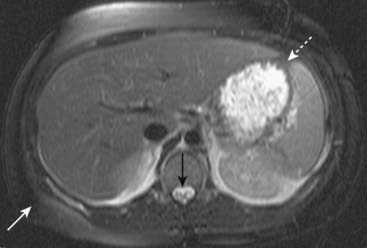

We can tell that this is a T2-weighted image because the CSF in the spinal canal is bright (solid black arrow). Also, it is a fat-suppressed image because the subcutaneous (solid white arrow) and intraabdominal (dotted white arrow) fat are dark. Fat is normally bright on a T2-weighted image without fat suppression.

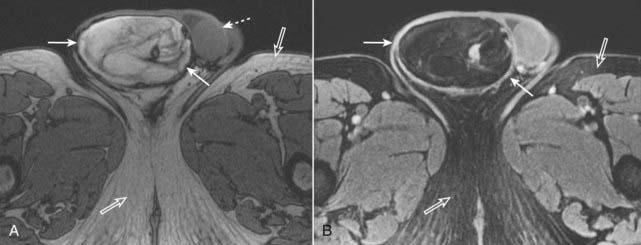

Figure 20-9 Fat in a liposarcoma of the right spermatic cord.

A, Axial T1-weighted image of the scrotum demonstrates a bright, heterogeneous right scrotal mass (solid white arrows). The left testis is unremarkable (dotted white arrow), and the right testis is not visualized. Note that subcutaneous fat is normally bright (open white arrows). B, Axial T1-weighted, fat-suppressed, gadolinium-enhanced image demonstrates that the bright signal in the right scrotal mass is now dark, consistent with fat (solid white arrows). The subcutaneous fat of the thighs is also dark (open white arrows). This was an unusual malignancy of the spermatic cord derived from fat cells.

MRI Contrast: General Considerations

Gadolinium-based contrast agents are used in the same fashion that iodinated contrast media is used in CT. They can be injected intravascularly or intraarticularly.

Gadolinium-based contrast agents are used in the same fashion that iodinated contrast media is used in CT. They can be injected intravascularly or intraarticularly. After intravenous injection, Gd-DTPA enters the blood pool, enhances organ parenchyma, and then is excreted by the kidneys via glomerular filtration.

After intravenous injection, Gd-DTPA enters the blood pool, enhances organ parenchyma, and then is excreted by the kidneys via glomerular filtration.

T1 shortening will cause a brighter signal on T1-weighted images, and it is for this reason that images obtained after gadolinium administration are usually T1-weighted to take advantage of this effect.

T1 shortening will cause a brighter signal on T1-weighted images, and it is for this reason that images obtained after gadolinium administration are usually T1-weighted to take advantage of this effect. Fat is bright on T1 even before the administration of gadolinium. In order to increase detection of contrast enhancement in fat, the precontrast and postcontrast images are typically fat-suppressed (meaning darkened) to enhance the effect of the gadolinium (Fig. 20-10).

Fat is bright on T1 even before the administration of gadolinium. In order to increase detection of contrast enhancement in fat, the precontrast and postcontrast images are typically fat-suppressed (meaning darkened) to enhance the effect of the gadolinium (Fig. 20-10). Structures that become bright on postgadolinium images are typically vascular (such as tumors) (Fig. 20-11) and inflammation (Fig. 20-12), and are described as enhancing.

Structures that become bright on postgadolinium images are typically vascular (such as tumors) (Fig. 20-11) and inflammation (Fig. 20-12), and are described as enhancing.

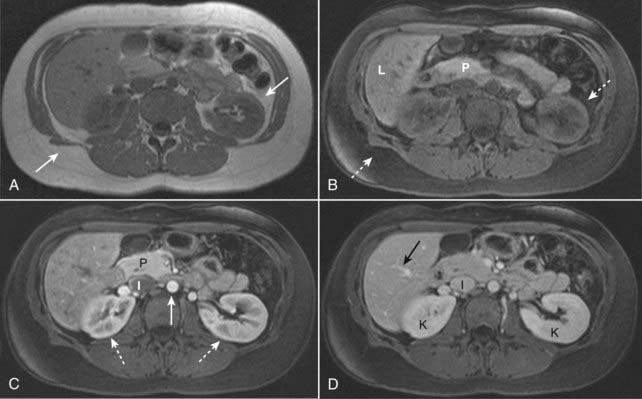

Figure 20-10 Fat suppression and normal enhancement of the abdomen following the administration of intravenous gadolinium.

A, T1-weighted image of a normal abdomen demonstrates normal bright subcutaneous and intraabdominal fat (solid white arrows). B, T1-weighted, fat-suppressed image shows that the signal from the fat has been suppressed (dotted white arrows) and is now dark. Intraabdominal organs such as the pancreas (P) and liver (L) now appear brighter relative to the adjacent suppressed fat. C, T1-weighted, fat-suppressed, early phase post-gadolinium image shows the normal enhancement of the aorta (solid white arrow) which enhances earlier than the inferior vena cava (I). The kidneys demonstrate normal corticomedullary phase enhancement (dotted white arrows), and the pancreas (P) enhances maximally during this phase. D, T1-weighted, fat-suppressed, later phase post-gadolinium image shows that the hepatic veins (solid black arrow) and inferior vena cava (I) are now well enhanced. The kidneys (K) now demonstrate normal homogeneous enhancement, the optimal phase to detect renal masses.

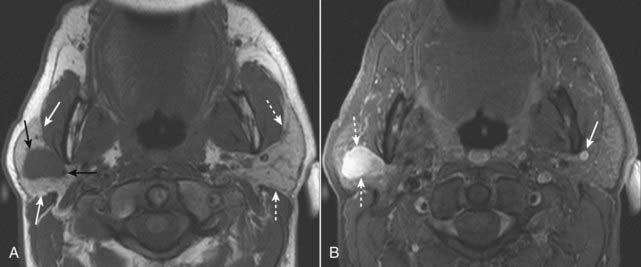

Figure 20-11 Right parotid pleomorphic adenoma.

A, Axial T1-weighted image of the neck demonstrates a dark, ovoid mass with a slightly lobular contour (solid black arrows) located within the right parotid gland (solid white arrows). The left parotid gland is unremarkable (dotted white arrows). B, Axial T1-weighted, fat-suppressed, post-gadolinium enhanced image demonstrates that the right parotid mass is very bright due to intense enhancement (dotted white arrows). Surgical resection of this mass yielded a pleomorphic adenoma, the most common benign tumor of the parotid gland. A clue that this image is a gadolinium-enhanced image is the presence of bright, enhancing vascular structures such as the left retromandibular vein (solid white arrow).

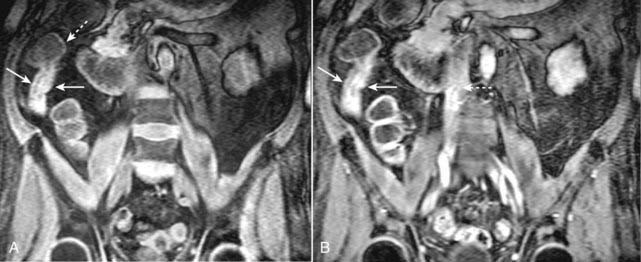

Figure 20-12 Active inflammation in Crohn disease.

A, Coronal T1-weighted fat-suppressed image from an MR enterography examination demonstrates thickening of the wall of the distal terminal ileum (solid white arrows). The adjacent cecum is normal (dotted white arrow). B, Coronal T1-weighted, fat-suppressed, gadolinium-enhanced image demonstrates marked enhancement of the wall of the terminal ileum (solid white arrows) indicating that this wall thickening represents active inflammatory narrowing of the lumen. Gadolinium is also seen within the inferior vena cava (dotted white arrow), a finding that helps us determine that this is an enhanced image.

MRI Safety Issues

Claustrophobia

Ferromagnetic Objects

Any ferromagnetic object inside the patient can be moved by the magnetic field of the MR scanner and could damage adjacent tissues. Such internal ferromagnetic objects also hold the potential to be heated and cause burns to surrounding tissues.

Any ferromagnetic object inside the patient can be moved by the magnetic field of the MR scanner and could damage adjacent tissues. Such internal ferromagnetic objects also hold the potential to be heated and cause burns to surrounding tissues.

![]() Ferromagnetic objects in a location where motion of the object may be harmful to the patient represent an absolute contraindication to MR imaging. These objects include medically inserted items such as cerebral aneurysm repair clips, vascular clips, and surgical staples. Many vascular clips and staples are now manufactured to be MRI-compatible.

Ferromagnetic objects in a location where motion of the object may be harmful to the patient represent an absolute contraindication to MR imaging. These objects include medically inserted items such as cerebral aneurysm repair clips, vascular clips, and surgical staples. Many vascular clips and staples are now manufactured to be MRI-compatible.

Some foreign bodies, such as bullets, shrapnel, and metal in the eyes (as can be seen in metal workers) can also be ferromagnetic.

Some foreign bodies, such as bullets, shrapnel, and metal in the eyes (as can be seen in metal workers) can also be ferromagnetic.

Ferromagnetic objects outside of the patient such as oxygen tanks, scissors, scalpels, and metallic tools, also pose a risk to the patient as they could become airborne once they enter the magnetic field and for this reason are strictly forbidden in the MRI scanning room. Nonferromagnetic equipment (“MR-safe equipment”) is now available, and is used for MRI-guided procedures such as biopsies.

Ferromagnetic objects outside of the patient such as oxygen tanks, scissors, scalpels, and metallic tools, also pose a risk to the patient as they could become airborne once they enter the magnetic field and for this reason are strictly forbidden in the MRI scanning room. Nonferromagnetic equipment (“MR-safe equipment”) is now available, and is used for MRI-guided procedures such as biopsies.Mechanical or Electrical Devices

![]() MRI cannot be performed in patients who have pacemakers, pain stimulator implants, insulin pumps, other implantable drug infusion pumps, and cochlear implants.

MRI cannot be performed in patients who have pacemakers, pain stimulator implants, insulin pumps, other implantable drug infusion pumps, and cochlear implants.

Pregnant Patients

Although there are no known biological risks associated with MR imaging in adults, the effects of MRI on the fetus are not definitely known (Fig. 20-13).

Although there are no known biological risks associated with MR imaging in adults, the effects of MRI on the fetus are not definitely known (Fig. 20-13).

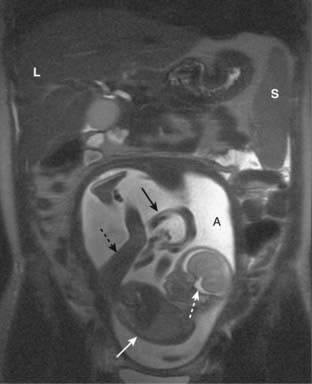

Figure 20-13 MRI in pregnancy.

Coronal T2-weighted image demonstrates an intrauterine pregnancy. The maternal liver (L) and spleen (S) are partially imaged. The bright amniotic fluid (A) and fetal CSF (dotted white arrow) help us to recognize this image as a T2-weighted image. The fetal body (solid white arrow) and leg (dotted black arrow) can be seen clearly. The umbilical cord (solid black arrow) is partially visualized.

![]() Because only limited data exists and because the fetus is more susceptible to injury in the first trimester of pregnancy, pregnancy is considered by some to be an absolute contraindication to MR imaging due to theoretical harmful effects to the fetus.

Because only limited data exists and because the fetus is more susceptible to injury in the first trimester of pregnancy, pregnancy is considered by some to be an absolute contraindication to MR imaging due to theoretical harmful effects to the fetus.

The American College of Radiology, however, states that pregnant patients can undergo MRI scans at any stage of pregnancy if it is decided that the risk-benefit ratio to the patient weighs in favor of performing the study.

The American College of Radiology, however, states that pregnant patients can undergo MRI scans at any stage of pregnancy if it is decided that the risk-benefit ratio to the patient weighs in favor of performing the study.Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis

In patients with renal insufficiency, gadolinium-based contrast agents have been associated with a rare, painful, debilitating, and sometimes fatal disease called nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF).

In patients with renal insufficiency, gadolinium-based contrast agents have been associated with a rare, painful, debilitating, and sometimes fatal disease called nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF).Diagnostic Applications of MRI

Some of the many clinical uses of MRI are outlined in Table 20-1. The chapters in which some of the diseases are discussed in greater detail are indicated.

Some of the many clinical uses of MRI are outlined in Table 20-1. The chapters in which some of the diseases are discussed in greater detail are indicated.| System | Organ | Diseases |

|---|---|---|

| Musculoskeletal | Evaluate bone marrow menisci, tendons, muscles | Meniscal tears; ligamentous and tendon injuries; contusions |

| Bones | Occult or stress fractures | |

| Osteomyelitis | High negative predictive value if normal | |

| Spine (Chapter 24) | Disk disease and marrow infiltration; differentiating scarring from prior surgery from new disease | |

| Neurologic | Brain (Chapter 25) | Ideal for studying brain, especially posterior fossa; tumor, infarction; multiple sclerosis |

| Peripheral nerves | Impingement; injury | |

| GI | Liver (Chapter 18) | Characterize liver lesions; detect small lesions; cysts, hemangiomas; hepatocellular carcinoma; focal nodular hyperplasia; hemochromatosis; fatty infiltration |

| Biliary system (Chapter 18) | Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography for strictures, ductal dilatation | |

| Small and large bowel | MR enterography; appendicitis in pregnant females | |

| Endocrine/reproductive | Adrenal glands | Adenomas; adrenal hemorrhage |

| Female pelvis | Anatomy of uterus and ovaries; leiomyomas; adenomyosis; ovarian dermoid cysts; endometriosis; hydrosalpinx | |

| Male pelvis | Staging of rectal, bladder, and prostate carcinoma | |

| GU | Kidneys | Renal masses; cysts versus masses |

Weblink

Weblink

Registered users may obtain more information on Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Understanding the Principles and Recognizing the Basics on StudentConsult.com.

![]() Take-Home Points

Take-Home Points

MRI: Understanding the Principles and Recognizing the Basics

MRI uses a very strong magnetic field to influence the electromagnetic activity of hydrogen nuclei, also called protons.

Protons each have a charge and possess a spin. The constant movement of protons generates a small magnetic field causing the proton to behave like a mini-magnet. When the protons are placed in the much more powerful magnetic field of the MRI scanner, they all align with this external magnetic field.

A radiofrequency (RF) pulse, transmitted by a transmitter coil, displaces the protons from their original alignment with the external magnetic field of the scanner.

When the RF pulse is turned off, the displaced protons relax and realign with the main magnetic field, producing a radiofrequency signal (the echo) as they do so. Receiver coils receive this signal (or echo) given off by the excited protons. A computer reconstructs the information from the echo to generate an image.

The main magnet in an MRI scanner is usually a superconducting magnet that is cooled to extremely low temperatures in order to carry the electrical current.

There are three major types of coils within the MRI scanner: volume, surface, and gradient coils.

Pulse sequences consist of a set of imaging parameters that determine the way a particular tissue will appear. The two main pulse sequences that all MRI pulse sequences are based on are called spin echo (SE) and gradient recalled echo (GRE).

T1 and T2 are both time constants. T1 is called the longitudinal relaxation time, and T2 is called the transversal relaxation time.

TR is the repetition time between two RF pulses. A short TR creates a T1-weighted image.

TE is the echo time between a pulse and its resultant echo. A long TE creates a T2-weighted image.

On T1-weighted images, fat, hemorrhage, proteinaceous fluid, melanin, and gadolinium are typically bright (white).

On T2-weighted images, fat, water, edema, inflammation, infection, cysts, and hemorrhage are typically bright.

In summary, fat is T1-bright and T2-bright. Water is T1-dark and T2-bright.

Suppression is a feature of MRI that will cancel out or eliminate signal from certain tissues and is most often used for fat. Although normally T1-bright, fat will be dark on T1-weighted fat suppressed images. Fat suppression is particularly useful for tissue characterization after administration of gadolinium.

Gadolinium is the most common intravenous contrast agent used in clinical MR imaging, and its effect is to shorten the T1 relaxation time of hydrogen nuclei yielding a brighter signal. Vascular structures such as tumors and areas of inflammation enhance after gadolinium administration and become more conspicuous.

Ferromagnetic objects must be kept outside of the MRI scanning room as they could become airborne when exposed to the magnetic field. Patients who may have metallic foreign bodies in their eyes must first have conventional orbital radiographs to see if metal is present.

In pregnancy, MRI is preferred in the second and third trimester, and gadolinium is contraindicated.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is a debilitating fibrotic disease that can occur in patients with renal insufficiency who receive intravenous gadolinium-based contrast agents. Therefore, gadolinium is typically avoided in patients with severe renal disease.