Chapter 7 Podiatry in the management of leprosy and tropical diseases

INTRODUCTION

The use of podiatric skills in the management of foot and lower limb conditions has continued to widen and it is now seen as essential to use podiatric interventions in a range of situations where the underlying pathology is not common in temperate climates. The value of such intervention, particularly in the case of leprosy, has been shown to be capable of giving significant improvement to the life of the sufferer. The present-day podiatrist now needs to be aware of an ever-widening range of conditions that present clinically, particularly as international air travel makes it possible for conditions that were previously seen solely in the tropics to be a not too uncommon occurrence in temperate zones.

LEPROSY

Hansen’s disease (HD), or hanseniasis, are preferred terms for leprosy as they do not evoke the connotations that leprosy does. Once an individual has been diagnosed as having leprosy, his or her role in society will lead to an inevitable social death. The patient’s experience of the disease is profoundly affected by the social beliefs and expectations of the society of which the individual is a part. Leprosy is not simply a dysfunction of physiological order, it also has psychosocial manifestations that profoundly affect the patient’s family and community.

Ironically, the tragedy of leprosy has little to do with the bacillus that causes the disease. The general perception of leprosy within a community is confined to conditions associated with the characteristic secondary deformities. Thus it is possible that, long after Hansen’s disease has been cured, the sequelae of the disease, unless controlled, may continue to deform and disable the patient. It is such patients who will then continue to be perceived as having leprosy. Impairment control is a practicable objective, but it demands life-long vigilance. The podiatrist has a specialised approach to chronic pedal disorders. Podiatric training is, therefore, particularly appropriate for the implicit needs of impairment control. The podiatrist is trained to accept the challenge posed by incurable conditions and is uniquely facilitated to develop a provider–receiver relationship that can protect the patient physically and rehabilitate him or her socially.

Epidemiology

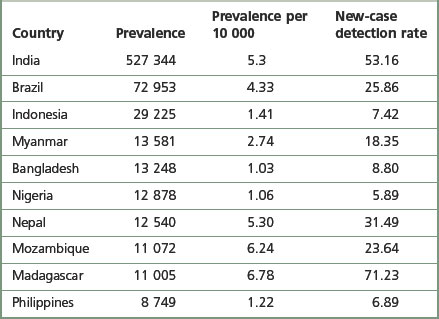

Hansen’s disease is essentially a problem in developing countries. Findings published by the World Health Organization in 1998 showed that, globally, there were 804 436 registered cases (WHO 1999). The Indian subcontinent remains the region with the highest prevalence; however, in 1998 prevalence was declining in India, whereas it was increasing in Brazil. Countries with the highest prevalence rates are shown in Table 7.1. There have been problems with the interpretation of the data because case definitions vary between countries.

Table 7.1 Countries with the highest prevalence rates of Hansen’s disease in 1998 (WHO 1999)

The prevalence figures only suggest the number of people registered for treatment, and do not give any indication of those who are ‘cured’ but remain permanently impaired. Figures for the total number of leprosy-affected people are not available, but they could number millions.

After diabetes mellitus, Hansen’s disease is the most common cause of sensory neuropathy globally, and is probably the major cause of neuropathy in Asia and Africa, where it affects predominantly the lower socio-economic groups.

The mode of transmission remains a topic of investigation, and the three possible routes are the respiratory tract, the skin and the gastrointestinal tract. Direct skin-to-skin contact is no longer considered the most likely form of transmission, as it appears that Mycobacterium leprae is not capable of penetrating the papillary zone of the dermis. However, transmission through skin abrasions has not been excluded (Jopling & McDougal 1988).

Aerosol contamination remains the most likely form of transmission, and there is evidence that demonstrates that infected droplets can be expelled during sneezing, coughing and even talking. Droplets may also be absorbed by dust, and viable M. leprae has been identified in desiccated secretions a week after expectorating. The principal theory of transmission is that contaminated droplets are inspired, M. leprae enters the capillaries around the alveoli and then continues to target cells via a haematological route. It has also been suggested that damage to the nasal mucosa provides an accessible portal of infection from the same source. The most significant target cell is the Schwann cell, but M. leprae is also found in significant numbers in macrophages, endothelium, chondrocytes and melanocytes.

The bacillus is not virulent; infected subjects can host vast numbers without feeling any ill effect, and chemotherapy rapidly compromises the viability of the bacillus. It is therefore from undiagnosed, multibacillary hosts that the threat of infection is greatest.

Classification

Host resistance to the bacillus will determine the classification of the disease type. The Ridley–Jopling classification is the most widely respected, but more simple classification systems are now used in most field programmes. The Ridley–Jopling classification describes the spectrum of disease from tuberculoid (TT), which demonstrates vigorous resistance and low infection (paucibacillary (PB)), to lepromatous (LL), which demonstrates severely compromised resistance and massive infection (multibacillary (MB)). Borderline (BB) describes resistance that lies between the two polar responses. Further subdivisions are made that represent responses that lie between the principal responses (Jopling & McDougal 1988).

Neuropathy in tuberculoid leprosy

The most significant changes in tuberculoid leprosy involve the cutaneous and subcutaneous nerves. Nerve damage is an inherent effect of host response and is not related to massive proliferation of bacilli. Infected nerves are invaded and destroyed beyond recognition by epithelioid granulomae. An intense response to infection may lead to necrosis and the development of nerve abscesses. Where a nerve trunk is affected, the sensorimotor deficit will be superimposed, giving rise to the localised mixture of neurological defects characteristic of tuberculoid leprosy. The destruction of dermal nerves explains the localised anaesthetic patches, sometimes the only indication of polar tuberculoid leprosy. Autonomic loss is a feature of tuberculoid lesions, where axon reflex and sweating are found to be absent. Involvement of nerve trunks, being in proximity to skin lesions, is probably secondary to cutaneous nerve involvement. The most frequently affected nerves in the lower limb are the common peroneal and the posterior tibial nerves. The saphenous and the sural nerves are less commonly affected.

Neuropathy in lepromatous leprosy

Due to depressed cell-mediated immunity in lepromatous leprosy, the haematogenous spread of the bacilli allows the unchecked proliferation of bacilli. Nerve damage is slower to become apparent than in other forms of leprosy. While bacilli continue to multiply within Schwann cells and perineurium, others are dispersed with the destruction of the same. Liberated bacilli are engulfed by histiocytes in which they are not destroyed, and the histiocyte becomes a vehicle that transports multiplying bacilli to other regions of the nerve or other tissues. It is these cells that are known as lepra cells, carrying masses of bacilli collectively called globi.

Symmetrical and bilateral sensory loss of lepromatous leprosy is explained by the massive and widespread distribution of bacilli. The sites of nerve lesions appear to be related to body temperature. Sabin and Swift (1984) presented repeated patterns of surface temperature obtained by thermographic scanning of normal subjects. By comparing gradients between different body temperatures and the evolution of neurological deficit, a clear relationship between the usual distribution of surface temperatures and sensory loss was demonstrated.

Neuropathy in borderline (dimorphous) leprosy

While nerve damage in borderline leprosy is essentially limited to the same sites as those common in lepromatous leprosy, the potential for uncharacteristic neurological defects is greater. Cases of borderline leprosy demonstrate the greatest potential for catastrophic peripheral nerve damage. This is explained by a dual effect. An inadequate host response ensures that an initial haematogenous spread of disease is not prevented. However, unlike lepromatous leprosy, there is a degree of resistance, resulting in a prompt and radical response when bacilli are detected. As a result, widespread, tuberculoid-type nerve damage is demonstrated early in the disease.

Where a borderline case demonstrates a tendency to fall closer to the tuberculoid pole (BT), paralysis and sensory loss are always asymmetrical. Where borderline cases lie at the midpoint of the spectrum (BB), involvement is asymmetrical and indicates intracutaneous nerve dysfunction because the borders of insensitivity do not conform to dermatomes. In a low-resistance borderline case (BL) there will be numerous lesions, symmetrically distributed. Areas of insensitivity may exceed the borders of lesions, and temperature-linked patterns of sensory loss become apparent. However, the spread of involvement is less diffuse than in lepromatous leprosy and is not as symmetrical (Sabin & Swift 1984).

The lower limb in Hansen’s disease

Anaesthesia

The integrity of the foot is dependent on safety information relating to current conditions of the substratum. The high density of Vater–Pacini corpuscles in the subcutaneous fat chambers provides an acute sense of deep pressure and vibration. These modalities are associated with high-frequency shock and tissue displacement, whereas it is postulated that the Meissener’s corpuscles register low-frequency shock. The dual effect of these modalities is that the foot’s movement against the ground and the character of the weight-bearing surface may be perceived. The ability to register pressure coupled with withdrawal and postural reflexes is essential for self-protection (Jorgensen & Bosjen-Moller 1991). The major factor compromising the foot in Hansen’s disease is anaesthesia. Denied the benefits of sensory feedback, the undesirable effects of pathomechanical forces are undetected. Tissue may be strained by mechanical stress beyond its threshold of competence, in which case it breaks down.

Factors associated with plantar ulceration

Motor paralysis

It has been suggested that only 6% of ulcerated feet display anaesthesia alone; when the foot was further compromised by intrinsic muscular paralysis, this figure was increased ten-fold (Brand 1991). It is probable that paralysis of the intrinsic muscles increases the vulnerability of the foot by creating instability during propulsion. The extent to which pre-existing functional abnormalities could exacerbate this condition has not been widely considered.

Claw toes

Claw toe deformity is a common feature of the neuropathic foot in Hansen’s disease and is generally considered to indicate intrinsic muscle paralysis. (The development of the deformity should not be taken as a qualification for muscle paralysis per se, as muscle imbalance due to other mechanical factors is also a cause of claw toe deformity (Root et al 1977).) The extension of the proximal phalanges results in the plantar flexion of the metatarsal heads and anterior drifting of the fibrofatty pad. Compromised by the loss of digital stabilisation, the metatarsal heads are exposed to abnormally directed, excessive forces, focused on a reduced area of loading. Extreme peak pressure readings have been reported under the ulcerated metatarsal heads of leprosy-impaired subjects (Bauman et al 1963).

Extrinsic muscle paralysis

M. leprae appears to have a predilection for cooler sites, such as the peroneal nerve as it winds around the fibular neck. This site is particularly vulnerable to infiltration. Peroneal and anterior compartment paralysis is not uncommon. The resulting foot drop deformity can severely compromise an affected person. Excessive lateral and forefoot loading predisposes the patient to ulceration, particularly under the fifth metatarsal head. The plantar flexors and posterior tibialis have not been found to be affected by neuropathy in Hansen’s disease.

Pre-existing pathomechanical foot function

Factors of a congenital and/or developmental origin affecting foot function are probably implicated in the development of plantar ulceration. It has been reported that 85% of plantar ulcers occur in the forefoot, with the remaining 15% occurring in the heel (10%) and lateral border (5%) (Brand 1991). The predilection for forefoot ulceration suggests that standing pressure and injury are less likely to be causative factors than is walking.

Of initial ulcers that occur on the forefoot, the most common sites are:

The frequency of occurrence at these sites suggests an association with excessive or abnormal loading, which is generally associated with compensatory subtalar pronation for rearfoot or extrinsic abnormalities.

Tarsal disintegration

In late lepromatous leprosy, a complication may be the massive infiltration of bacilli into the bones of the foot. Such infiltration may cause rarefaction of cancellous bone and some loss of trabeculae. Mechanical stress, during phases of acute infiltration, can result in fracture and disintegration of tarsal bones. In most cases of this nature, the acute phase is followed by a period of recalcification. During this period, the skeleton either returns to normal, if undamaged, or is reorganised following disintegration or fracture. Tarsal disintegration as a direct consequence of infiltration is unusual (about 1% of all cases of leprosy).

A more common cause of disintegration and absorption is a periosteal osteoclastic action, which occurs as a consequence of hyperaemia following ulceration (Kulkarni & Mehta 1983). It is, however, the combination of neuropathy and pathomechanical foot function that most disadvantages the patient with Hansen’s disease. Talonavicular and calcaneocuboid instabilities have been implicated as major compromising features, as tarsal disintegration most commonly begins from either of these joints. Excessive calcaneal eversion, with subtalar pronation, may result in the impingement of the lateral process of the talus into the crucial angle of the calcaneus. A splitting of the calcaneus at this location is also a common early feature of tarsal disintegration.

Absorption and pathological fractures

Brand (1991) recorded that just over 33.3% of patients with Hansen’s disease show distinct radiological changes in the bones and joints of the feet. These changes are caused either by infiltration of M. leprae (4%) or by secondary changes, including periostitis, osteoporosis, and sequestration with associated pathological fractures and disintegration of bone. M. leprae has been described as a specific pathogen with a predilection for infecting bone (in multibacillary disease). However, the more common invasive and destructive nature of non-specific osteomyelitis is attributed to secondary infection. Active secondary infection of ulceration may lead to periostitis and osteomyelitis, which commonly leads to sequestration.

Hyperaemia, associated with chronic plantar ulceration, and active infection of bone can also cause osteoporosis. The osteoporotic state of bone predisposes it to pathological fractures, particularly when pain sensation in the joints is lost. Fracture and infection may lead to absorption of bone, giving rise to short foot or tarsal disintegration. The gross organisation of such feet predisposes them to further ulceration due to the vulnerability of the tissue beneath bony prominences.

Autonomic impairment

The impairment of dermal sympathetic nerve function may result in the loss of sweat and axon reflexes. Dehydration of the epidermis results in the loss of keratin flexibility and elasticity. The integrity of the skin is therefore compromised and tensile stress causes fatigue and breakdown. Apart from being a contributory factor affecting ulceration, anhidrosis very commonly causes fissures, which are a potentially serious complication for patients as they provide a portal for infection (Fig. 7.1).

Social and behavioural variables

Hansen’s disease is predominantly a problem among lower socio-economic groups. Patients are constrained to continue working to avoid dependence on family members and loss of dignity. Very often the employment opportunities available to sufferers are limited to manual labour and agricultural occupations, where patients are compelled to submit their feet to excessive demands and are unable to rest (Fig. 7.2). Poverty dictates that such patients are unable to purchase suitable footwear, if indeed they can purchase any at all. Podiatry has mainly focused therapeutic developments around the interaction between the foot and footwear. Treating underprivileged, unshod populations is a daunting challenge.

Complications of ulceration

Secondary infection

Common causative organisms implicated are Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus haemolyticus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus mirabilis and Escherichia coli. Aggravated by continuous mechanical forces in the absence of pain, infection spreads rapidly along tendon sheaths and into synovial joint spaces. Infective arthritis and osteomyelitis are common sequelae found in a ‘complicated ulcer’.

Squamous-cell carcinoma

The chronic irritation of regenerating epithelium around an ulcer and osteomyelitis with chronic discharging sinuses are two of the predisposing factors thought to influence the development of squamous-cell carcinoma. Hyperplasia, influenced by chronic irritation, initiates the regeneration of cells, which manifest as papillomatoses adapted to irritation. Continued irritation leads to dysplasia with decreasing cell differentiation and, ultimately, carcinoma (Sane & Mehta 1988).

Treatment of pedal pathologies

When treating Hansen’s-disease-related foot problems in developing countries, the availability of materials and medications will dictate management options. A sound understanding of therapeutic principles, a pragmatic philosophy and imaginative resourcefulness will be the key attributes of the successful clinician in such circumstances.

Ulceration

The treatment of neuropathic ulceration should aim to enhance the normal response to trauma. The physiological response to wound healing follows a recognised sequential pattern. The biochemical and cellular responses, demonstrated as inflammation, proliferation and maturation, demonstrate a continuous process that aims to restore continuity and tissue strength. Where the overlapping phases of inflammation, epithelialisation, contraction and connective tissue formation are continuously disrupted, the process of resolution or organisation is confounded by the effects of chronic inflammation. Chronic inflammation is perpetuated by foreign-body irritation and repeated microtrauma. A prolonged inflammatory response is associated with a delay in tissue regeneration and consequent retarded development of tissue tensile strength.

The normal physiological response to ulceration demonstrates three phases:

The active phase of ulceration

The leucocytic migration to a traumatised location results in the active debridement and solubilisation of devitalised tissue. Complementing phagocytic activity is the monocytic production of collagenase and proteoglycan-degrading enzymes. Associated with the increased migration of macrophages and plasma proteins is the accumulation of transudate. The normally clear, straw-coloured serous exudate displays discoloration and odour, reflecting its altered status as a cellular aggregate. The viscous and purulent aggregate of cells and debris that drains from an opened wound is a sterile exudation. Within a week, the cells and plasma constituents of the exudate cease to function and become incorporated into a necrotic coagulum. Necrotic tissue (slough) may remain relatively fluid or dehydrates to become a hardened eschar. In the active phase of ulceration, discharge is copious. The volume of exudate inhibits the consolidation of materials to form an eschar. Oedema and infection can contribute considerably to the amount of exudate expressed.

Unresolved disruptive forces perpetuate haemostatic mechanisms. The occlusion of microcirculation serves to exacerbate the anoxic necrosis of tissue. Where pressure is implicated as a precipitating factor, endothelial cells lining the microcirculation become separated. The resultant separation of junctional complexes allows contact between procoagulants of the blood and subendothelial tissues, notably collagen, causing an aggregation of platelets. Platelet aggregation leads to vascular occlusion and further tissue necrosis (Barton 1976, Cruickshank 1976).

The pathological process during the destructive phase of ulceration causes the lesion to spread inwards, thereby destroying subcutaneous tissue faster than the overlying skin. The undermined edges of active ulcers are a characteristic feature (Fig. 7.3). Recently formed and active ulcers have been described as exhibiting a mobile relationship with deeper tissues. The organisation of fibrous tissue associated with chronicity results in the lesion being tied to deeper structures, thereby reducing its mobility. The indurated and punched-out edges of chronic ulceration are the manifestation of the accumulation of collagen (Kloth & Miller 1990).

The proliferative phase of ulceration

Granulation. A primary indication of ulcer resolution is the appearance of granulation tissue at the base of an ulcer. Granulation tissue is a vascular and lymphatic system in a gel-like matrix, contained within a fibrous collagen network. The matrix is composed of hyaluronic acid and fibronectin, with other salts and colloidal materials. The vascular network carries nutrients to macrophages and fibroblasts, while the lymphatics prevent oedema. Granulation tissue is produced until the wound cavity is filled, reducing the depth of the ulcer almost to the level of the surrounding skin (Thomas 1990).

Re-epithelialisation. The spread of granulation to the level of the skin stimulates the activation of the epithelium, which begins to proliferate over the wound (Thomas 1990). It has been suggested that wounded tissue does not produce chalones, and therefore that the separated surfaces at a free edge would not be subject to the inhibitory effect of chalone on biological events. This hypothesis may explain the common occurrence of hyperkeratinisation around the periphery of ulcers (Daly 1990).

Factors influencing healing during the active and proliferative phases. Vitamin C and oxygen are fundamental factors influencing the hydroxylation of proline and lysine. When there is a deficit of these factors there follows an inhibition of collagen synthesis. Vitamin A deficiency has been recorded as delaying re-epithelialisation. Protein deficiency results in an amino acid deficit, causing a consequent lack of availability of material to structure granulation tissue. Protein deficiency may have an inhibiting effect on host defence against infection. Deficiency of trace elements, particularly zinc and copper, has been implicated as a cause of delayed healing (Daly 1990, Westaby 1982, Zederfeldt et al 1986).

Other factors recorded as inhibiting wound healing include systemic and topical steroids, antineoplastic drugs, haemostatic agents, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, nicotine and many systemic antibiotics. Local conditions may be compromised by the effects of antimicrobial toxicity, while dressings may adversely affect healing by creating an unsuitable environment for this process (Daly 1990, Westaby 1982).

The maturation or remodelling phase of ulceration

An outline of events characterising this phase includes the decline in concentration of fibroblasts and the complex reorientation of collagen fibres. The result is eventual consolidation of scar tissue, which displays a maximum strength of 20% less than that of intact skin. The realignment of collagen fibres is thought to be a response to pressure. When pressure is applied, collagen releases piezoelectric substances. It is postulated that these stress-generated voltages are responsible for the realignment and general maintenance of collagen (Price 1990).

Mal perforans

Complicated ulcers (Fig. 7.4) extend to involve tendons, synovial sheaths, joint capsules and bone. Pyogenic infection of bone may result from the localisation of infection via a haematogenous route or from abscesses. Infection may lead to chronic osteomyelitis with multiple sinus formation. A more common causative factor contributing to involvement of deeper tissue is secondary infection of an uncomplicated ulcer. Sequestration, remodelling of bone and copious periosteal reaction are associated with pyogenic infection. In such cases, restoration of tissue stability is dependent on overcoming infection and the removal of necrotic bone and soft tissue. In the absence of compromising factors, complicated ulcers proceed to heal by secondary intention.

Enhancing the healing process

Factors that should be taken into account include:

Infection control

Hansen’s disease is not associated with generally compromised immunological defences. Where other variables are addressed, healing is usually faster than diabetic ulceration, because Hansen’s disease is not complicated by vascular disease. The immune system may, however, be suppressed by systemic and topical steroid therapy, malnutrition and nicotine. These factors should be considered when planning infection control. The choice of antiseptic medicaments should be balanced between the perceived threat of infection and the cytotoxicity of available medicaments.

Maintaining an optimal wound environment

The general principles of ulcer management are that the lesion should be kept clean and clear of slough, avascular or necrotic soft tissue (see Ch. 10). Overlying callus and epidermis should be excised to reduce stress and encourage healing by secondary intention. Excessively discharging complicated lesions or hypergranulating lesions indicate investigation for sequestrae or other foreign bodies, which must be removed.

The lesion should be kept moist at all times. During the active phase, dressings capable of absorbing exudate are indicated. During the proliferative and remodelling phases there is greater danger from the wound becoming too dry; the choice of dressings should be considered accordingly.

An ideal wound environment can be maintained where the following are ensured:

Rest

Wherever possible, patients with acute ulceration should be treated with bed rest and medication. Where this is possible, after a week the oedema and discharge will have diminished and a walking plaster can be applied. Plaster casting is contraindicated for profusely discharging ulcers. If, after a week, the ulcer continues to discharge copiously, involvement of bony tissue should be considered. Swelling subsides rapidly when the foot is immobilised, and unless the plaster is removed after the first week, the cast may become loose and problematic. Further plaster casts can be applied and changed depending on the rate of discharge from the ulcer, looseness of cast and the extent of wear. Although ulcers have been known to heal within 3 weeks, the patient should be advised not to expect healing before 6 weeks. Attention to plaster-casting technique cannot be overemphasised. Well-applied plaster, appropriately placed padding, and either a rubber heel or wooden rocker will immobilise the foot and distribute forces over the foot and up the leg.

Debate continues about the efficacy of window casting. The advantage is that direct access is given to the ulcer for dressing and assessment. The major disadvantage is that oedema can result in the protrusion of the ulcer into the window. In such cases healing is delayed and the ulcer is vulnerable to further trauma.

Orthotic options

Simple ulcers of 1 cm diameter have been shown to heal using appropriate appliance therapy (Cross et al 1995, 1996). Appliance therapy is also particularly useful for the preservation of the foot after healing by plaster casting. The recurrence of ulceration after cast removal is a common problem.

Resource availability will dictate orthotic prescription and manufacture. There is no substitute for a thorough grounding in functional anatomy, biomechanics and the therapeutic rationale supporting appliance therapy.

Note. Functional orthoses should not be supplied unless the patient can be monitored diligently.

Orthotic prescription is based on:

Detailed screening and examination may indicate patients at risk of ulceration or tarsal disintegration. Timely orthotic intervention may be a valuable adjunct to other disability-prevention measures (ILEP Medical Commission 1993, Watson 1986).

Case studies

The context. Case studies 7.1 and 7.2 were recorded at the Lalgadh Leprosy Services Centre, Nepal. The centre serves a rural community in an area of high endemicity for leprosy (18 per 10 000). The region in which the hospital is situated is underdeveloped, and as a consequence the catchment area is extensive. People may walk for 2 days to avail themselves of services; however, for most a visit to the Outpatient Department constitutes a full day away from home and employment. Cultural factors dictate that women (apart from the destitute) may not travel unaccompanied. Very few people are able to visit more frequently than once a month, and for many even this is not an option due to economic pressures.

CASE STUDY 7.1 IMPAIRMENT CONTROL

History. A 14-year-old boy presented at the Outpatient Department. The patient’s father had become suspicious of the hypopigmented patches on the boy’s face and legs and had brought his son for further investigations. Neither the patient or his father were certain of the time since the appearance of the patches. However, it was approximately a year since the patient’s peers had noticed the patches and had begun to persecute him.

There was no previous history of Hansen’s disease in the family.

ON EXAMINATION

Skin examination. The anaesthetic macules demonstrated a morphology typical of borderline tuberculoid leprosy.

Nerve function assessment. Sensory testing was conducted using Semmes–Weinstein monofilaments (Brandsma 1994) and the boy was found to present with sensory loss affecting the plantar aspects of both feet. The development of anhidrotic fissures was evidence of possible autonomic palsy. There was no loss of muscle function affecting the lower limb, but a weakness of fifth finger function (right hand) suggested impairment of the ulnar nerve. Following careful questioning it was ascertained that the posterior tibial nerve function impairment was of approximately 4 months duration and that the ulnar nerve impairment was of approximately 2 months duration.

Biomechanical assessment. On weight-bearing examination the boy presented with excessively pronated subtalar joints in the relaxed calcaneal stance position. This was considered to be a compensation for marked genu varum. The neutral calcaneal stance position demonstrated that when the subtalar joint was neutral the calcaneums were aligned at 10° inversion.

On non-weight-bearing examination of the feet no forefoot abnormalities were found.

Gait analysis revealed that aphasic subtalar pronation extended throughout the gait cycle.

TREATMENT

The boy and his father were counselled carefully to enable them to accept that the boy did have Hansen’s disease and that he required treatment with multidrug therapy for 1 year.

He was supplied with abendazole for the treatment of intestinal infestation prior to receiving an initial supply of steroids. A course of prednisolone, tapering after 2 weeks from an initial dose of 45 mg, was prescribed for the restoration of nerve function. (Steroid therapy is indicated where nerve function impairment is of less than 6 months duration.)

He was supplied with sandals supporting microcellular rubber soles. The sandals incorporated appliances, which have become known among leprosy organisations of the Indian subcontinent as ‘hatti pads’. The function of the appliance is essentially to limit the extent of pronation and to support the arch to facilitate better first-ray function. The hatti pad incorporates a heel meniscus where the medial aspect is broader than the lateral aspect and is angled to limit the extent to which the heel may otherwise evert. It extends to include an arch support. The arch support is carefully designed and manufactured to give maximum support beneath the navicular. It slopes anteriorly to end immediately proximal to all the metatarsal heads (except the fifth) and laterally to the lateral tread line. It thus conforms closely to the architecture of the arch.

The boy and his father were offered places in the Self-care Training Centre to assist the boy in his orientation to the disease and its treatment. The Self-care Training Centre offers a 14-day programme that aims to enable people affected by leprosy to learn how to adopt safe practices for the prevention of further impairment and possible disability. A further objective is that on completion of the course people affected by leprosy will be better able to cope with possible psychosocial effects of the disease.

FOLLOW-UP

The boy returned monthly for monitoring and supply of drugs, footwear and foot appliances. He did recover function in the ulnar nerve but sensory function was not restored to the plantar surfaces of his feet. Up to the time of reporting this study he has avoided plantar ulceration and has managed to maintain his plantar skin in reasonably good order. He has adjusted well to the disease and receives strong family and community support.

CASE STUDY 7.2 IMPAIRMENT MANAGEMENT, DISABILITY LIMITATION AND SOCIAL EMPOWERMENT

HISTORY

A woman of uncertain age (between 25 and 35 years) presented at the Outpatient Department with a foul-smelling plantar ulcer on her left foot.

The patient’s file catalogued a complex history over the previous 6 years. Four years earlier she had completed treatment for lepromatous leprosy, complicated by recurrent episodes of type 2 reaction and iritis. Since cure from the disease she had presented on numerous occasions and had been treated for ulceration of her hands and feet.

The patient had extensive impairments, including an anaesthetic clawed right hand, an anaesthetic left hand with loss of index and ring fingers and clawing and shortening of other fingers. Both feet were anaesthetic. The patient’s right foot had undergone extensive damage, resulting in short foot deformity, while her left foot had lost all toes. The patient’s nasal septum had collapsed.

The records related that the patient had lost two children and that her husband had evicted her from their home. Until recently, she had been living in a neighbour’s buffalo shed where her husband and others had from time to time sent her food.

ON EXAMINATION

An ulcer issuing copious foul-smelling exudate was found beneath the first metatarsal head. The distal aspect of the lower left leg was hot, and on palpation the left groin lymph node was found to be swollen and very tender.

Further examination using a probe revealed that the metatarsal head was fragmenting. Some maggots were extricated from recesses in the wound.

The patient was found to be detached and unresponsive to questioning.

DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s primary presenting problem was an acute infected complicated ulcer with osteomyelitis of the first metatarsal head. Secondary effects were cellulitis and lymphadenectasis.

TREATMENT

The patient was admitted for treatment of an acute septic condition.

As an inpatient, immediate bed rest with elevation of the limb was ordered. Following consultation, the physician prescribed amoxicillin, gentamicin and intravenous infusion of Ringer’s lactate.

Necrotic soft tissue was excised, sequestrae were removed and the distal end of the metatarsal shaft was resurfaced. Further examination revealed that the infection had begun to track along the sheath of flexor hallucis longus. An incision was made proximally to expose the tendon and 2 cm of infected tendon was excised. Betadine packing with a secondary gauze dressing was applied and the wound was bandaged. Following examination the next day secondary sutures were applied.

Betadine dressings were applied until the removal of sutures. Following the removal of sutures saline dressings were applied for a further week, after which a walking plaster was applied for 4 weeks. On removal of the plaster the wound had resolved to the extent that it had become a simple ulcer. At this stage the patient began self-care of the ulcer.

During conversations with the patient it became apparent that she was unable to wear protective footwear in her village due to the censure of the community. Simple self-care procedures (soaking and oiling of plantar and palmar skin) also drew strong negative reactions. It was also apparent that the attitude of the community had seriously eroded the patient’s self-esteem, making it unlikely that she would be motivated to take any appropriate precautionary measures. A further stage of the treatment, therefore, was to address the social pathology. A visit was made to the village where discussion with village leaders and the patient’s neighbours gave an opportunity to educate the community concerning the true nature of the problem. Having the benefit of understanding, the community agreed to take positive action to help the patient. It was also agreed that Lalgadh Leprosy Services would establish means by which she would become less dependent on the community for economic assistance (in this instance breeding goats were supplied for the patient).

During the remainder of her period of admission a biomechanical assessment was undertaken. The patient’s right foot had been reduced to little more than an apropulsive prop. It was essential, therefore, to locate areas that would be vulnerable to the effects of high pressure and to manufacture an appropriate ‘moulded’ insole to palliate the foot.

The patient’s left foot presented with a pronated subtalar joint during weight bearing. On non-weight-bearing examination the loss of the first metatarsal head resulted in a superior displacement of the medial aspect of the forefoot. The potential for high shearing stress injury resulting from late and excessive subtalar pronation to compensate for the iatrogenic forefoot varus was considered a high risk. The medial aspect of the foot was also extremely vulnerable due to the recent episode of ulceration. For this foot a tarsal cradle constructed from microcellular rubber was prescribed.

Both appliances were manufactured and placed into custom-made microcellular rubber sandals. These were supplied with Velcro fittings for ease of wear with deformed hands.

FOLLOW-UP

The patient continued to return on an occasional basis for repeat footwear/appliance supply. The patient’s social conditions had improved, as had her attitude. However, she did continue to present with simple ulcers on the plantar aspect of her right ‘short foot’. The episodes were much less frequent and the injuries very much less severe on presentation.

TROPICAL DISEASES

Skin infection and tropical diseases presenting on the foot may represent a primary condition or a secondary manifestation of illness elsewhere in the body. Cutaneous larva migrans, madura foot and localised cutaneous simple leishmaniasis are examples of the former, whereas the latter can be exemplified by systemic conditions such as leprosy, disseminated leishmaniasis and coccidioidomycosis.

When approaching a patient with a tropical skin disease on the feet the podiatrist should carry out a thorough exercise in history taking. This must include detailed information on previous skin disease, travel history, occupation, duration of signs and symptoms, evolution of clinical signs, and a fast practical assessment of the patient’s immune status. The identification of extracutaneous signs such as fever, enlarged lymph nodes and general malaise indicate systemic illness, and these findings should prompt immediate action for an appropriate referral. Particular epidemiological settings determine exposure and attack rates of specific diseases, and hence an understanding of the global geographical pathology and living conditions of the overseas population is required.

The prevalence of skin diseases in the tropics is similar to that found in developed countries. The main differences found in tropical settings are a higher incidence of endemic infectious diseases, a lower frequency of skin malignancy, and a lack of or decreased availability of podiatric and dermatological services. Moreover, poor living conditions, overcrowding and malnutrition account for a variety of cutaneous signs and symptoms related to poverty. A vast number of tropical diseases manifest on one or both feet, and this chapter contains up-to-date information on this field of podiatry. The following sections are organised to present the most relevant conditions grouped by aetiological agents, and the main emphasis is on clinical findings and diagnosis as a practical guide to everyday work in podiatry. Pathogenesis of disease and management of conditions are also included.

Bacterial infections

Pyogenic infections

Aetiology and pathogenesis

Common bacterial infections of the skin are caused by Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species. These infectious agents are ubiquitous in both urban and rural environments, and are capable of causing disease in individuals of all age groups. Healthy and immunocompromised hosts develop pyogenic infections of the foot following direct inoculation of bacteria. Less often, haematogenous dissemination to the lower limb, and even a septicaemic state, may develop as a result of a minor injury on the foot. The port of entry for these pathogenic organisms is often unnoticed by both the patient and doctor, but minor injuries, insect bites, friction blisters or superficial fungal infection are the commonest means of entry found in clinical practice. Other clinical circumstances, such as burns, use of indwelling catheters in children and surgical procedures, also play a role as risk factors for these infections.

Pyogenic bacteria cause damage in the infected tissue by the pathogenic action of proteases, haemolysins, lipoteichoic acid and coagulases. Erythrogenic toxins are responsible for the erythema commonly observed on feet infected by Streptococcus species (Bisno & Stevens 1996).

Clinical findings and diagnosis

The clinical spectrum of pyogenic infections of the foot includes folliculitis, furuncle and carbuncle formation on areas with hair follicles. Plaques of impetigo and infiltrated thickened dermis can affect any region of the foot, and are caused by Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species, respectively. Abscess formation, cellulitis, and necrotic ulceration represent the more severe end of the spectrum.

The perimalleolar regions are far more commonly affected than other areas of the foot, as they are exposed to mechanical trauma. The dorsum, toes and heels follow in frequency.

Common clinical signs of pyogenic infections include a variety of manifestations such as erythema, inflammation, pus discharge, abscess formation, ulceration, blistering, necrotising lesions and gangrene (Figs 7.5-7.8). Most pyogenic skin infections are painful.

The diagnosis of pyogenic infection of the foot is based on the clinical history and findings. Bacteriological investigations and sensitivity profile to antibiotics must be carried out if possible. Disseminated, chronic or severe infections require an immediate referral to a dermatologist or an infectious disease specialist.

Management and treatment

Mild infections are successfully treated by bathing or soaking the affected foot in potassium permanganate solution (1 : 10 000 dilution in water) for 15 minutes daily. Other mild superficial infections, such as isolated plaques of impetigo or impetiginised eczema, respond well to antiseptic or antimicrobial creams and ointments containing cetrimide, chlorhexidine, fucidic acid or mupirocin. Acute or chronic foot eczema requires treatment with potent topical steroids in order to eliminate risk factors for infection. Infections with multiple lesions, or those involving larger areas of the foot, require a complete course of systemic β-lactam or macrolide antibiotics in addition to the above topical treatments. Recurrent episodes of cellulitis require longer courses of these antibiotics, and hospitalisation followed by surgical debridement is mandatory in necrotic lesions, gangrenous plaques and deeper infections with severe fasciitis. Superficial infections of the foot skin complicated by deeper involvement with necrosis of soft tissues carry a high mortality rate (up to 25%) (Elliot et al 1996).

Treponemal infections

Cosmopolitan treponemal diseases such as secondary syphilis present with an asymptomatic, symmetrical papular eruption and scaling of plantar regions (Fig. 7.8). Other clinical features, such as concurrent palmar involvement, the history of a primary chancre and the characteristic trunkal rash, confirm the clinical suspicion. A definitive diagnosis can be established by specific tests such as a positive dark-field microscopy from early skin lesions, as well as from highly sensitive treponemal serology (Young 1992). Despite the fact that syphilis is not strictly a tropical disease, it represents a significant problem for the returning traveller involved in high-risk sexual activities while in the tropics (WHO 1986). The treatment of choice is penicillin, but allergic individuals respond to erythromycin or tetracyclines.

Yaws is a treponemal tropical disease manifesting on the feet and periorificial skin on the face. This condition affects mainly the male rural population in South America, Sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia. This disease is associated with poverty in the humid tropics (Sehgal et al 1994) and one of the characteristic clinical presentations is that of plantar hyperkeratosis. Late tertiary infection results in asymptomatic palmoplantar keratoderma that develops nodular hyperkeratotic lesions leading to painful disability; hence the characteristic walk known as ‘crab yaws’. The clinical picture can be difficult to differentiate from that of other types of infectious and non-infectious plantar keratodermas. Tests for diagnosis include dark-field microscopy of early lesions and treponemal serology. The treatment of choice is penicillin but Treponema pallidum pertenue also responds to tetracyclines and macrolides.

Other bacterial infections manifesting on the foot

Tropical seaborne infections by halophilic Vibrio vulnificus can produce localised or systemic disease manifested by acute and painful erythema, purpura, oedema and necrosis on one or both feet. The infection is acquired by direct traumatic inoculation in estuaries and seawater, or by ingestion of raw seafood, particularly oysters. Male individuals with a history of liver disease and iron-overload states are the group at highest risk of this infection (Serrano-Jaen & Vega-López 2000). Severe cases require immediate referral to a specialist hospital physician, as intravenous antibiotics and early surgical debridement represent the treatment of choice.

Exfoliation of the plantar skin is part of the complex and severe picture in cosmopolitan cases with staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) (Cribier et al 1994), whereas necrotic ulceration of the foot can result from tropical cutaneous diphtheria caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae (Belsey & LeBlanc 1975). Cutaneous diphtheria commonly manifests as a non-healing single ulcerated lesion on the toe or toe cleft lasting between 4 and 12 weeks.

Mycobacterial infections

Aetiology and pathogenesis

Several mycobacterial species can cause primary or secondary infection of the foot. The ‘swimming’ or ‘fish-tank granuloma’ is an infection caused by Mycobacterium marinum. Other common chronic mycobacterial tropical infections include leprosy, tuberculosis and Buruli ulcer. These are caused by Mycobacterium leprae, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium ulcerans, respectively. Mycobacterial skin diseases can be acquired by direct skin contact with a patient, by direct accidental or occupational inoculation, and by inhalation of the infective organisms. Particular clinical forms of cutaneous tuberculosis result following haematogenous dissemination from a primary infection elsewhere. The respiratory route is particularly important for leprosy and diverse forms of pulmonary tuberculosis. In the case of Buruli ulcer it has recently been suggested that contact with infected water in rural areas of Africa may represent the main source of infection. A toxin called mycolactone seems to be responsible for the severe tissue destruction and ulceration seen in patients with Buruli ulcer (Thangaraj et al 1999). In general, however, it is accepted that agents causing mycobacterial skin diseases have a low pathogenic potential, as most infected individuals in endemic regions do not develop clinical mycobacterial diseases.

Mycobacteria are very complex organisms; most of them are ubiquitous in nature as saprophytes, but a number of species cause disease in other animals. A very thick wall surrounds the cytoplasmic membrane of mycobacteria and contains virulence factors such as proteins and glycolipids. Mycobacteria can inhibit an efficient phagocytosis and intracellular killing by macrophages and can also interact with the host’s immune cells. This interaction results in chronic inflammation, tissue damage, and immunopathology, all of which account for the signs and symptoms observed in the wide range of mycobacterial diseases.

Clinical findings and diagnosis

Fish-tank granuloma

This affects more commonly the fingers or hand dorsum but it has also been described on the foot. M. marinum frequently infects freshwater fish, and hence individuals handling fish tanks represent the main population at risk (Gray et al 1990). Direct inoculation into the foot presents with similar clinical findings to those found in infections of the upper limb. The disease manifests as a localised progressing swelling with variable pain, and the appearance, within a few weeks, of nodular or verrucous skin lesions on the affected area. These lesions can show ulceration and bleeding from the disease process itself but also from mechanical trauma. The nodular lesions, measuring from a few millimetres up to 2–3 cm, may resolve spontaneously after a few months, but they can also disseminate proximally by haematogenous or lymphatic spread. The dorsal aspects of the foot and the malleolar regions are exposed to trauma, and therefore direct inoculation commonly takes place on these regions. Once the condition is suspected, microbiological and histopathological investigations represent the most sensitive tests to confirm the clinical diagnosis.

Leprosy

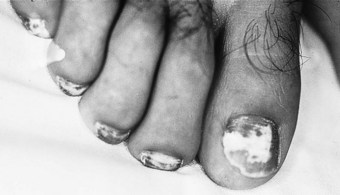

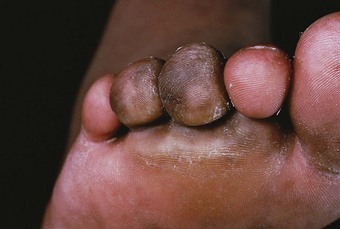

Advanced disease manifests with skin atrophy, pigmentary changes and, in severe cases, chronic ulceration leading to disability (Fig. 7.9). Mutilating lesions of the toes result from bone resorption, mechanical trauma, and secondary bacterial infection.

The clinical diagnosis of leprosy can be easily established in most cases that occur in endemic regions of the world (Bryceson & Pfaltzgraff 1990). Epidemiological, clinical, histopathological, bacteriological and immunological criteria have been used for many years to diagnose and classify the cases of leprosy within a disease spectrum. This spectrum considers two polar groups or forms, called tuberculoid and lepromatous, as well as intermediate forms of the disease defined as borderline. Early disease may not present characteristics of any of the above groups and such cases are called indeterminate. Patients with early disease, and particularly those presenting to the podiatrist in countries non-endemic for leprosy, often pose diagnostic difficulties. The delay in establishing an accurate diagnosis and treatment inevitably results in irreversible nerve damage and chronic complications with variable degrees of disability.

Skin tuberculosis

This affects individuals of all ages and both sexes, who present with a wide variety of clinical pictures that frequently affect the lower limbs and particularly one or both feet (Chopra & Vega-López 1999). However, lupus vulgaris and papulonecrotic tuberculide are more common in females, whereas tuberculosis verrucosa cutis is rare in children. By far the main clinical presentation of cutaneous tuberculosis affecting the adult foot is called tuberculosis verrucosa cutis. The tuberculous bacilli cause disease following direct inoculation into the skin but clinical disease can also result from haematogenous dissemination. Unilateral involvement is the rule in almost all cases. Commonly observed asymptomatic lesions include dry patches of atrophic skin, pigmentary changes, nodules and plaques of verrucous lesions. The total plaque of tuberculosis can measure 2–12 cm in diameter, but chronic and larger lesions can involve most of the foot dorsum and lateral aspects. The course of cutaneous tuberculosis is indolent and chronic, but determines skin atrophy and variable degrees of scarring with a consequent degree of local skin insufficiency. The clinical diagnosis can be confirmed by histopathology, bacteriology and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) investigations.

Buruli ulcer

This affects mainly young individuals in rural Africa – and particularly in West Africa where an increase in incidence has been reported (Thangaraj et al 1999). More than two-thirds of the cases present in children below the age of 15 years. The initial lesions present as papules or small nodules that slowly increase in size to the point of causing an area of inflammation and subsequently ulceration of the skin. The ulcer characteristically presents with undermined edges and manifests active indolent phagedenism, often involving large areas of the affected limb. A single ulcer, or smaller coalescing ulcers, present more frequently on the lower leg above the ankles, but other regions of the foot can be involved as well. Oedematous forms may progress rapidly and cause a panniculitis with destruction of underlying tissues such as fascia and bone. In cases where a large ulceration is followed by healing, contractures of the affected limb result from scarring. Severe scarring and contractures have been identified as a high morbidity factor for disability and up to 10% require amputation of the deformed limb (Josse et al 1994).

Management and treatment of mycobacterial infections

All mycobacterial diseases require highly specialised diagnostic investigations that, in many cases, can be carried out only in a tertiary hospital setting. Most mycobacterial diseases affecting the skin represent public health priorities, not only in the endemic countries where they occur but also at an international level as established by the WHO. Following the diagnosis of individual cases, a long-term multidrug therapeutic regimen can be prescribed only by specialised physicians. Mycobacteria are known to develop resistance to antibiotics, and it is imperative that all cases be treated with combinations of at least two drugs. The main drugs with antimycobacterial activity are rifampin, ethambutol, pirazinamide, clofazimine, sulfone, isoniazide, macrolide antibiotics, tetracyclines and quinolones. The management of all mycobacterial diseases must consider not only the medical treatment but also a full range of educational initiatives aimed at the patient, the community and the health personnel. Early lesions of fish-tank granuloma, skin tuberculosis, and particularly those caused by Buruli ulcer require surgical excision.

Bacterial mycetoma

Aetiology and pathogenesis

Nocardia, Actinomadura and Streptomyces species are the common aetiological agents of ‘madura foot’ or actinomycetoma. This form of bacterial mycetoma occurs in tropical countries, and the main case series have been reported from Sudan, Senegal, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, India and Mexico. The infection is acquired by direct inoculation of bacteria into the skin. Young male individuals living in endemic regions and dedicated to agricultural activities have been reported to have the highest incidence of actinomycetoma (López-Martínez et al 1992). Bacteria causing actinomycetoma have a thick wall surrounding the cytoplasmic membrane that is rich in lipid and carbohydrate compounds. Some of these compounds, such as lipoarabinomannan and mycolic acids, have been identified as virulence factors. These bacteria are capable of blocking the adequate killing mechanisms by the cells of the infected host; however, it is considered that they have a low pathogenic potential and most of them live as saprophytes in the soil.

Clinical findings and diagnosis

The clinical disease is characterised by a chronic course, with inflammation, formation of sinus tracts discharging ‘grains’ and progressive deformity of the affected foot (Fig. 7.10). Healing of discharging sinus tracts over the years determines scarring, with atrophic skin plaques and secondary pigmentary changes. Asymptomatic nodular or verrucous lesions can also be found, and in a few cases a variable range of symptoms is present. These include pain that often results from superimposed pyogenic infection, acute inflammation and bone involvement. The chronic infection with deformity of the foot determines periosteal involvement and subsequently osteomyelitis. Variable but often severe degrees of disability complete the chronic course of actinomycetoma.

The clinical picture manifested on one foot is highly suggestive of the diagnosis. The main differential diagnosis includes mycetoma caused by fungi (see the section on eumycetoma, below) but other forms of ‘cold’ abscess formation, histoplasmosis, chromoblastomycosis, cutaneous tuberculosis and sarcoidosis are the other main conditions to consider. Direct microscopy to disclose the ‘grains’ discharged from sinus tracts confirms the diagnosis, and the culture of this material also provides a definite diagnosis of actinomycetoma.

Management and treatment

Effective drugs against the agents of bacterial mycetoma include streptomycin, dapsone and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxasol (Welsh 1991). Recently, a report revealed efficacy with a combination of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxasol, amikacin and immunomodulators (Serrano-Jaén, personal communication, 1999). The treatment has to be administered for several months and the therapeutic response is variable. Early cases of mycetoma presenting with small lesions can be cured by surgical excision. In contrast, advanced cases with periosteal involvement and those with osteomyelitis do not respond to medical treatment, and radical surgery of the foot represents the only therapeutic option.

Parasitic diseases, ectoparasite infestations and bites

Cutaneous larva migrans

Aetiology and pathogenesis

This dermatosis results from the accidental penetration of the human skin by parasitic larvae from domestic canine and feline hosts. Cats and dogs pass ova of these helminths within the stools and larval stages develop in the soil or beach sand. Close contact with human skin allows the infective larvae to burrow into the epidermis and cause clinical disease. The main aetiological agents are Ancylostoma brasiliensae, A. caninum, A. ceylanicum and A. stenocephalae but other species affecting ruminants and pigs can also cause human disease. Following penetration into the skin, the larvae are incapable of crossing the human epidermodermal barrier, and stay in the epidermis creeping across spongiotic vesicles until they die a few days or weeks later. Multiple infections can, however, last for several months.

Clinical findings and diagnosis

The plantar regions of one or both feet represent the main anatomical site affected by cutaneous larva migrans, but any part of the body in contact with infested soil or sand can be involved. Individuals of all age groups and both sexes can be affected, and the disease is a common problem for tourists on beach holidays where they walk bare foot or lie on the infested sand. A report of 50 cases presenting in returning travellers attending a specialised clinic in London revealed that 70% of the lesions were located on one foot (Blackwell & Vega-López 2000). The initial lesion is a pruriginous papule at the site of penetration that appears within a day following the infestation. An erythematous, raised, larval track measuring 1–3 mm in width and height starts progressing in a curved or looped fashion (Fig. 7.11). New segments of larval track reveal that the organism can advance at a speed of 2–5 cm/day. Commonly, the larval track measures between a few millimetres up to several centimetres in the region adjacent to the penetration site, but uncommon cases may present long larval tracks surrounding large areas of the foot with a well-defined perimalleolar distribution. Localised clinical presentations on the toes may present with only papular lesions, but other presentations include blisters and urticarial wheals. Secondary complications to the presence of the parasite in the epidermis include an inflammatory reaction, eczematisation, impetiginised tracks or papules, and even deeper pyogenic infections. Variable in severity, but most commonly intense, pruritus and burning sensation are the main symptoms.

The diagnosis is based on the clinical history and physical findings on the affected skin. The histopathological investigation has little, if any, value in the diagnosis of cutaneous larva migrans. The study of 332 cases in central Mexico over 10 years in the 1980s (Orozco, personal communication, 1993) revealed that haematoxylin–eosin (HE) preparations of affected skin show a spongiotic acute or subacute dermatitis with a variable presence of larval structures. A mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate was frequently observed in the dermis, and a low proportion of cases may develop peripheral eosinophilia, but this is not a constant finding.

Management and treatment

The treatment of choice is the systemic administration of albendazol for 3 days. Topical options include a 10% thiabendazol cream applied several times daily for 10 days, and one or more sessions of cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen. Resistant cases may respond to a single dose of systemic ivermectin (Caumes et al 1992).

Leishmaniasis

Aetiology and pathogenesis

Leishmania species parasites are protozoan organisms transmitted to humans and other vertebrates by the bite of female sandflies of the genera Phlebotomus or Lutzomya. Most Leishmania species can cause skin or mucocutaneous disease, but a few of them affect internal organs as well. It is estimated that 15 million individuals are infected by Leishmania in 88 countries. The main endemic foci are found in Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Southern Europe and Latin America. Hot and humid environments such as those found in rain forest jungles provide adequate habitats for the vectors in Latin America. In contrast, desert conditions favour breeding sites for the vectors in the Middle Eastern and North African endemic regions (WHO 1990).

Following the bite from a Leishmania-infected sandfly, humans can either heal spontaneously or develop localised or disseminated skin disease. Sandfly and Leishmania species causing skin disease in humans have been classified in geographical terms as Old World and New World cutaneous leishmaniasis. Both can affect the skin of one foot, but multiple infective bites or disseminated forms may present with lesions on both feet. The bite of the sandfly commonly targets exposed areas such as the external ankles during walking or the medial regions of the foot when the host is at rest. Depending on the area left uncovered by light footwear, the foot dorsum, heel, toes, lateral aspect and plantar region can also be affected by bites.

Leishmania parasites can resist phagocytosis and damage by complement proteins from the host by the action of lipophosphoglycan and glycoprotein antigens. Following phagocytosis, the intracellular forms of Leishmania parasites induce a delayed-type hypersensitive granulomatous reaction, which adds to the tissue damage.

Clinical findings and diagnosis

The clinical picture of cutaneous leishmaniasis was recently reviewed by Chopra and Vega-López (1999). The bite of a sandfly may induce an inflammatory papular or nodular lesion of prurigo, but in some cases it may go unnoticed for several weeks. The incubation period can be as short as 15 days but commonly it is estimated at about 4–6 weeks. Certain forms may take longer to develop clinically. A non-healing papule with surrounding erythema and pain may also indicate superimposed bacterial infection that subsequently develops ulceration (Fig. 7.12). On average, 6–8 weeks after the sandfly bite a violaceous nodule, with or without nodular borders, starts to enlarge and ulcerate. The ulcer is partially or completely covered by a thick crust (Fig. 7.13) that, following curettage, reveals a haemorrhagic and vegetating bed. Cutaneous leishmaniasis on the foot can manifest clinically as nodules covered with crust, ulceration with a raised inflamed solid border, tissue necrosis and lymphangitic forms. Advanced late forms present with scarring, skin atrophy and pigmentary changes. The plantar regions may be affected by pigmented and hyperkeratotic lesions in a clinical form called ‘post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis’, which presents after an episode of visceral leishmaniasis.

The clinical picture of leishmaniasis on the foot and the history of exposure in an endemic region of the world strongly suggest the diagnosis. Complementary tests include histology of a skin specimen, slit skin smears stained with Giemsa for direct microscopy, and tissue samples for culture and for genetic analysis by PCR techniques.

Management and treatment

The general public and health personnel easily establish the diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis in endemic areas of the world. Following referral to a physician, one or more treatment options are available. However, in non-endemic regions, and particularly in non-tropical countries, the patient requires attention by a doctor experienced in tropical medicine, infectious diseases or dermatology. Several drugs are effective against Leishmania parasites and these include pentavalent antimonials, amphotericin B, triazole and alylamine antifungal compounds. However, the only treatment of choice for a number of species is the intravenous administration of antimonials carefully monitored in hospital and administered only by experienced personnel. A number of patients require long-term follow-up as leishmaniasis may relapse in some cases.

Gnathostomiasis

Aetiology and pathogenesis

A number of Gnathostoma species live as adult worms in the intestine of domestic cats. Humans can acquire the disease by eating contaminated fish that have ingested small crustaceans acting as intermediary hosts in this condition. The larval stages do not reach maturation in the human body and can cause disease in several internal organs as well as in the skin. The disease is prevalent in South East Asia, China, Japan, Indonesia and Mexico.

Clinical findings and diagnosis

Episodes of migrating, intermittent, subcutaneous oedema with pruritus constitute the main clinical picture, and cases can adopt a chronic protracted course for years. The episodes of oedema can be quite inflammatory and painful, and the larvae can erupt out from the affected skin. The feet are not commonly affected.

Management and treatment

The surgical extraction of the larva from the skin represents the curative therapeutic approach (Taniguchi et al 1992).

Tungiasis

Aetiology and pathogenesis

Tungiasis is a localised skin disease commonly affecting one foot and caused by the burrowing flea Tunga penetrans. This is also known as chigoe infestation, jigger, sandflea, chigoe and puce chique (in France). It has been reported that this flea originated in Central and South America (Ibanez-Bernal & Velasco-Castrejón 1996) and was subsequently distributed in Africa, Madagascar, India and Pakistan. It is a very small organism (~1 mm long) that lives in the soil near pigsties and cattle sheds. Fecundated females require blood, and their head and mouthparts penetrate the epidermis to reach the blood and other nutrients from the superficial dermis. After nourishment over several days, eggs are laid to the exterior and the flea dies.

Clinical findings and diagnosis

These fleas commonly affect one foot, penetrating the soft skin on the toe web spaces, but other areas of the toes and the plantar aspects of the foot can be affected (Douglas-Jones et al 1995). The initial burrow and the flea body can be evident in early lesions, but within 3–4 weeks a crateriform single nodule develops with a central haemorrhagic point. Superimposed bacterial infections may be responsible for impetigo, ecthyma, cellulitis and gangrenous lesions.

The diagnosis is clinical, but skin specimens for direct microscopy and histopathology with HE stain reveal structures of the flea and eggs.

Management and treatment

Curettage, cryotherapy, surgical excision or other careful removal of the flea and eggs are the curative therapeutic choices. Early treatment and avoidance of secondary infection are of the utmost importance in all infested hosts, and particularly in individuals with diabetes mellitus, leprosy or other debilitating conditions of the feet. A haemorrhagic nodule due to Tunga penetrans may be difficult to discern from an inflamed common wart or a malignant melanoma, but the short duration of the lesion and the history of exposure indicate the acute nature of this parasitic disease.

Myasis

Aetiology and pathogenesis

A number of diptera species in larval stages (maggots) may colonise the human skin. The infestation mechanisms include direct deposition of eggs, contamination by soil or dirty clothes, other insects acting as vectors, or actual penetration into the skin by larvae. Species of Dermatobia and Cordylobia are the commonest found in the tropics, in the Americas and Africa, respectively, whereas European cases originate from Hypoderma species (Lui & Buck 1992). A local inflammatory reaction to the larvae with secondary infection is responsible for the signs and symptoms of disease.

Clinical findings and diagnosis

Elderly and debilitated individuals of both sexes with exposed chronic wounds or ulcers are at a higher risk of suffering from this infestation. Furunculoid and subcutaneous forms may affect any part of the body, but in children the scalp is a commonly affected site. Chronic ulcers of the lower legs and feet represent a predisposing factor, and myasis often complicates severe infections by bacteria or fungi (see e.g. Fig. 7.18). Larvae feed on tissue debris and may not cause discomfort or any symptoms at all. Cases are observed throughout the year in tropical regions where the standards of hygiene, nutrition and general health are poor. The diagnosis is based on clinical suspicion and physical findings.

Management and treatment

The treatment of choice is the mechanical removal or surgical excision of the larvae (Lui & Buck 1992). Single furunculoid lesions can be covered by thick Vaseline or paste to suffocate the larvae that, following death, can be subsequently extracted. Superficial infestations respond to repeated topical soaks or baths in potassium permanganate solution over a few days.

Scabies

Aetiology and pathogenesis

Scabies is a cosmopolitan problem, but individuals in poor tropical countries with low standards of hygiene and, particularly, overcrowding suffer from cyclical outbreaks of severe and chronic forms. The human scabies mite Sarcoptes scabiei commonly affects the skin of both feet of infants and children. Adults rarely manifest scabies on the lower limbs below the knees (Hebra lines), but exceptional cases of crusted or Norwegian scabies may present with lesions on both feet. The scabies mite burrows a tunnel of up to 4 mm into the superficial layer of the epidermis, where eggs are laid. The eggs hatch and reach the stage of nymph, and subsequently become an adult male or female mite. Female individuals live for up to 6 weeks and lay up to 50 eggs. A new generation of fecundated females penetrates the skin in regions adjacent to the nesting burrow, but the mite infestation can also be perpetuated by clothes, or by reinfestation from another host in the family.

Clinical findings and diagnosis

Papules, with or without excoriation, and S-shaped burrows are the elementary classic lesions of scabies. Infants and young children present with papular, vesicular and/or nodular lesions on both plantar regions, but other parts of the feet can be affected. Children rarely have access to a consultation with a podiatrist, but adults with chronic crusted scabies may present with eczematisation, impetiginised plaques and hyperkeratosis similar to those observed in the paediatric case shown in Figure 7.14. Large crusts covering inflammatory papular lesions contain a high number of parasites, and careful examination is required to prevent the health personnel from acquiring the infestation.

The clinical findings and intense pruritus support the diagnosis. Confirmation is obtained by direct microscopy of skin scrapings from a burrow revealing the structures of the mite.

Management and treatment

Topical treatment overnight with benzyl benzoate, malathion, lindane or permethrine, lotion or cream, is usually effective. A second course is recommended 10 days after the original application, and all the affected members of a household require treatment at the same time to prevent cyclical reinfestations. Severe cases, or individuals in particular community settings such as those living in homes for the elderly, orphans, prisons or psychiatric wards, require oral treatment with a single dose of ivermectin as originally described by Macotela in 1991 (personal communication). This drug can be prescribed only by a qualified physician. Other therapeutic measures are directed at controlling the symptoms, inflammation and infection. Clothes and bed linen require washing at high temperature to kill all young fecundated females, but a number of authors have demonstrated that this is not necessary. In the right epidemiological context scabies may represent a venereal disease. Pruritus may last for several weeks after cure.

Ticks

Aetiology and pathogenesis

Ticks are cosmopolitan ectoparasites capable of transmitting severe viral, rickettsial, bacterial and parasitic diseases. The transmission of infectious agents takes place at the time of taking a blood meal from a human host that becomes infested accidentally. Soft ticks of the Argasidae family are more prevalent in the tropics and subtropical regions of the world and transmit agents of tick-borne relapsing fever.

Clinical findings and diagnosis

The bite of a tick is painful and the patient is aware of this episode. The bite produces a local inflammatory reaction, suggesting initially an ordinary papular insect bite, that subsequently causes localised superficial vascular damage with necrosis. The characteristic clinical picture manifests as an eschar that can be easily recognised on careful physical examination (Fig. 7.15). An area of circular scaling of the skin surrounding the original haemorrhagic bite can be seen after 7–10 days. Residual chronic lesions may leave hyperpigmented patches with a central induration.

Management and treatment

Careful removal of the tick can be carried out by applying a tight dressing or cloth impregnated with chloroform, petrol or ether on the tick body. The organism is carefully removed a few minutes later, avoiding the rupture of head and mouth parts, which can be left behind in the skin. A careful follow-up and self-surveillance is indicated as systemic illness may start a few days or weeks following the tick bite. Symptoms such as fever, skin rash, lymph node enlargement, fatigue and night sweats indicate systemic disease, and the patient requires referral to a hospital physician or a specialist in tropical medicine.

Fleas

Aetiology and pathogenesis

The common human flea Pulex irritans is cosmopolitan but a number of other species, such as the tropical rat flea Xenopsylla cheopis, show preference for tropical climates. Fleas bite humans in order to get a blood meal, and in so doing produce a localised inflammatory reaction. History of exposure can reveal that an individual host or family member recently moved house or acquired a second-hand piece of wooden furniture, where fleas can live for months without taking blood meals.

Clinical findings and diagnosis

A clinical picture of prurigo with papules, vesicles or small nodules on both feet and lower legs is characteristic, and the lesions are often found in clusters (Fig. 7.16). The papular discrete lesions may reveal a central haemorrhagic punctum, and the lesions in clusters often show a remarkable asymmetry. Modification of the initial pruriginous lesions may result from intense scratching and superimposed secondary bacterial infection.

Management and treatment

Fumigation can be successfully achieved by using common insecticide products approved for domestic use. Severe reactions of prurigo require a topical steroid cream, and impetiginised cases require topical or systemic antibiotics. Antihistamine lotions or tablets may provide symptomatic relief. Severe cases are treated with a single dose or short course of systemic corticosteroids.

Fungal conditions

Eumycetoma

Aetiology and pathogenesis