CHAPTER 11 Crying and Colic

CHAPTER 11 Crying and Colic

Crying can be a sign of pain, distress, hunger, or tiredness. Humans interpret their infants’ cries according to the context of the crying. The cry of a newborn at the time of delivery heralds the health and vigor of the infant. The screams of the same infant at 6 weeks of age after feeding, changing, and soothing may be interpreted as a sign of illness, difficult temperament, or poor parenting. Crying is a manifestation of infant arousal influenced by the environment and interpreted through the lens of the family, social, and cultural context.

NORMAL DEVELOPMENT

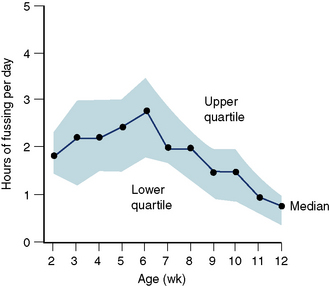

Understanding crying includes attention to the characteristics of timing, duration, frequency, intensity, and modifiability of the cry (Fig. 11-1). Most infants cry little during the first 2 weeks of life. Between 2 and 6 weeks, total daily crying duration increases from an average of 2 hours per day to 3 hours per day. By 12 weeks of age, the average daily duration of crying is 1 hour.

FIGURE 11-1 Distribution of total crying time among 80 infants studied from 2 to 12 weeks of age. Data derived from daily crying diaries recorded by mothers.

(From Brazelton TB: Crying in infancy, Pediatrics 29:582, 1962.)

Cry duration differs by culture and infant care practices; the duration of crying is 50% lower in the !Kung San hunter gatherers, who continuously carry their infants and feed them four times per hour, compared with infants in the United States. Crying may also relate to health status. Premature infants cry little before 40 weeks gestational age and tend to cry more than term infants at 6 weeks’ corrected age. Crying behavior in former premature infants also may be influenced by ongoing medical conditions, such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia, visual impairments, and feeding disorders. The duration of crying is modifiable by caregiving strategies.

Frequency of crying has less variability than duration of crying. At 6 weeks of age, the mean frequency of combined crying and fussing is 10 episodes in 24 hours (assessed by parental diary and voice-activated radiotelemetric tape recordings). Diurnal variation in crying is the norm, with crying concentrated in the late afternoon and evening.

The intensity of infant crying varies, with descriptions ranging from fussing to screaming. An intense infant cry (pitch and loudness) is more likely to elicit concern or even alarm from parents and caregivers than an infant who frets more quietly. Pain cries of newborns are remarkably loud: 80 dB at a distance of 30.5 cm from the infant’s mouth. Although pain cries have a higher frequency than hunger cries, when not attended to for a protracted period, hunger cries become acoustically similar to pain cries. Fortunately, most infant crying is of a lesser intensity, consistent with fussing.

COLIC

Colic often is diagnosed using the rule of threes—crying for more than 3 hours per day, for more than 3 days per week, for more than 3 weeks. The limitations of this definition include the lack of definition of crying (does this include fussing?) and the necessity to wait 3 weeks to make a diagnosis in an infant who has excessive crying. The crying of colic is often described as paroxysmal and may be characterized by facial grimacing, drawing up of the legs, and passing flatus.

Etiology

Fewer than 5% of infants evaluated for excessive crying have an organic etiology. Because the etiology of colic is unknown, this syndrome may represent the extreme of the normal phenomenon of infant crying. Nonetheless, evaluation of infants with excessive crying is warranted.

Epidemiology

Cumulative incidence rates of colic vary from 5% to 19% in different studies. Girls and boys are affected equally. Studies vary by how colic is defined and by data collection methodology, such as maintaining a cry diary or actual recording of infant vocalizations. Concern about infant crying also varies by culture, and this may influence what is recorded as crying or fussing.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinician who evaluates a crying infant must differentiate serious disease from colic, which has no identifiable etiology. The history includes a description of the crying, including duration, frequency, intensity, and modifiability. Does the infant have associated symptoms, such as pulling up of the legs, facial grimacing, vomiting, or back arching? When did the crying first begin? Has the crying changed? Does anything relieve or exacerbate the crying? Is there a diurnal pattern to the crying? A review of systems is essential because crying in an infant is a systemic symptom that can herald serious illness. Past medical history also is important, because infants with perinatal problems are at increased risk for neurologic causes of crying. Attention to the feeding history is crucial because some causes of crying are related to feeding problems, including hunger, air swallowing (worsened by crying), gastroesophageal reflux, and food intolerance. Questions concerning the family’s ability to handle the stress of the infant’s crying and their knowledge of infant soothing strategies assist the clinician in assessing risk for parental mental health comorbidities and developing an intervention plan suitable for the family.

The physical examination is an essential component of the evaluation of an infant with colic. The diagnosis of colic is made only when the physical examination reveals no organic cause for the infant’s excessive crying. The examination begins with vital signs, weight, length, and head circumference, looking for effects of systemic illness on growth, such as occur with infection or malnutrition. A thorough inspection of the infant is important to identify possible sources of pain, including skin lesions, corneal abrasions, hair tourniquets, skeletal infections, or signs of child abuse such as fractures (see Chapters 22 and 198). Infants with common conditions such as otitis media, urinary tract infections, mouth ulcerations, and insect bites may present with crying. A neurologic examination may reveal previously undiagnosed neurologic conditions, such as perinatal brain injuries, as the cause of irritability and crying. Observation of the infant during a crying episode is invaluable to assess the infant’s potential for calming and the parents’ skills in soothing the infant.

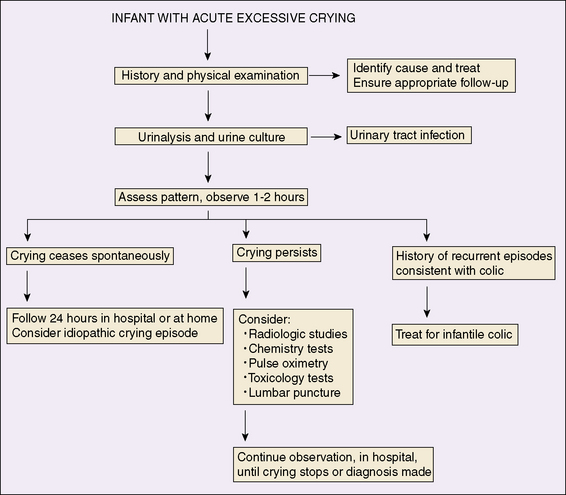

Laboratory and imaging studies are reserved for infants in whom there are history or physical examination findings suggesting an organic cause for excessive crying. An algorithm for the medical evaluation of an infant with excessive crying inconsistent with colic is presented in Figure 11-2.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for colic is broad and includes any condition that can cause pain or discomfort in the infant and conditions associated with nonpainful distress, such as fatigue or sensory overload (Table 11-1). Cow’s milk protein intolerance, maternal drug effects (including fluoxetine hydrochloride via breastfeeding), and anomalous left coronary artery all have been reported as causes of persistent crying. In addition, situations associated with poor infant regulation, including fatigue, hunger, parental anxiety, and chaotic environmental conditions, may increase the risk of excessive crying. In most cases, the cause of crying in infants is unexplained. If the condition began before 3 weeks’ corrected age, the crying has a diurnal pattern consistent with colic (afternoon and evening clustering), the infant is otherwise developing and thriving, and no organic cause is found, a diagnosis of colic is indicated.

TABLE 11-1 Diagnoses in 56 Infants Presenting to the Denver Children’s Hospital Emergency Department with an Episode of Unexplained, Excessive Crying

| Diagnosis | No. with Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Idiopathic | 10 |

| INFECTIOUS | |

| Otitis media* | 10 |

| Viral illness with anorexia, dehydration* | 2 |

| Urinary tract infection* | 1 |

| Mild prodrome of gastroenteritis | 1 |

| Herpangina* | 1 |

| Herpes stomatitis* | 1 |

| TRAUMA | |

| Corneal abrasion* | 3 |

| Foreign body in eye* | 1 |

| Foreign body in oropharynx* | 1 |

| Tibial fracture (from child abuse)* | 1 |

| Clavicular fracture (accidental)* | 1 |

| Brown recluse spider bite* | 1 |

| Hair tourniquet syndrome (hair wrapped tightly around digit) | 1 |

| GASTROINTESTINAL | |

| Constipation | 3 |

| Intussusception* | 1 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux* | 1 |

| CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM | |

| Subdural hematoma (bleeding around the brain from child abuse)* | 1 |

| Encephalitis* | 1 |

| Pseudotumor cerebri* | 1 |

| DRUG REACTION/OVERDOSE | |

| DTP reaction† | 1 |

| Inadvertent pseudoephedrine (cold medication) overdose | 1 |

| BEHAVIORAL | |

| Night terrors | 1 |

| Overstimulation | 1 |

| CARDIOVASCULAR | |

| Supraventricular tachycardia* | 2 |

| METABOLIC | |

| Glutaric aciduria type 1* | 1 |

| Total | 56 |

* Indicates conditions considered serious.

† From diphtheria/tetanus/pertussis (DTP) vaccine.

From Barr RG, et al: Crying complaints in the emergency department. In Crying as a Sign, a Symptom, and a Signal, London, 2000, MacKeith Press; with permission.

Treatment

The management of colic begins with education and demystification. When the family and the physician are reassured that the infant is healthy, and no infection, trauma, or underlying disease is present, education about the normal pattern of infant crying is appropriate. Learning about the temporal pattern of colic can be reassuring; the mean crying duration begins to decrease at 6 weeks of age and decreases by half by 12 weeks of age. Parents should not be told that colic resolves by 3 months of age; at that point the mean duration of crying is 1 hour per day. Approximately 15% of infants with colic continue to have excessive crying after 3 months of age.

Helping families develop caregiving schedules that accommodate the infant’s fussy period is useful. Techniques for calming infants include soothing vocalizations or singing, swaddling, slow rhythmic rocking, walking, white noise, and gentle vibration (e.g., a ride in a car). Giving caretakers permission to allow the infant to rest when soothing strategies are not working may alleviate overstimulation in some infants; this also relieves families of guilt and allows them a wider range of responses to infant crying. Avoidance of dangerous soothing techniques, such as shaking the infant or placing the infant on a vibrating clothes dryer (which has resulted in injury from falls), should be stressed.

Medications, including phenobarbital, diphenhydramine, alcohol, simethicone, dicyclomine, and lactase, are of no benefit in reducing colic and should be avoided. Parents, especially from Mexico and Eastern Europe, often use chamomile, fennel, vervain, licorice, and balm-mint teas. These teas have not been studied scientifically as remedies for colic. Families should be counseled to limit the volume of tea given because it displaces milk from the infant’s diet and may limit caloric intake.

Dietary changes should be considered in certain specific circumstances. There is rationale for change to a non–cow’s milk formula if the infant has signs of cow’s milk protein colitis. If the infant is breastfeeding, the mother can eliminate dairy products from her diet. In most circumstances, dietary changes are not effective in reducing colic, but they may appear to help because their use coincides with the natural reduction in crying between 6 and 12 weeks of age.

Prognosis

Infants with colic have not been shown to have adverse long-term outcomes in health or temperament after the neonatal period. Similarly, infantile colic does not have untoward long-term effects on maternal mental health. When colic subsides, the maternal distress resolves. Rarely, cases of child abuse have been associated with inconsolable infant crying.

Prevention

Much can be done to prevent colic, beginning with education of all prospective parents about the normal pattern of infant crying. Prospective parents often imagine that their infant will cry only briefly for hunger, not realizing that this may be beyond their control. Increased contact and carrying of the infant in the weeks before the onset of colic may decrease the duration of crying episodes. Similarly, other soothing strategies may be more effective if the infant has experienced them before the onset of excessive crying. Infants who have been tightly swaddled for sleep and rest during the first weeks of life often calm to swaddling during a crying episode; this is not true for infants who have not experienced swaddling before a crying episode. Parents also can be coached to learn to read their infant’s cues and ask themselves if the infant is hungry, uncomfortable, bored, or overstimulated. Parents also should be counseled that there are times when the infant’s cry is not interpretable, and caregivers can only do their best.