CHAPTER 67 Overview and Assessment of Adolescents

CHAPTER 67 Overview and Assessment of Adolescents

The leading causes of mortality (Table 67-1) and morbidity (Table 67-2) in adolescents in the United States are behaviorally mediated. Motor vehicle injuries and other injuries account for more than 75% of all deaths. Unhealthy dietary behaviors and inadequate physical activity result in adolescent obesity with associated health complications (e.g., diabetes, hypertension).

TABLE 67-1 Leading Causes of Death in Adolescents

| Rank | Cause | Rate (per 100,000) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unintentional injuries | 35.0 |

| 2 | Assault (homicide) | 9.3 |

| 3 | Suicide | 7.4 |

| 4 | Malignant neoplasms | 3.5 |

| 5 | Diseases of the heart | 2.0 |

| 6 | Congenital anomalies | 1.2 |

| 7 | Chronic respiratory disease | 0.5 |

| All others | Pulmonary disease, pneumonia, cerebrovascular disease | 8.9 |

From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics: Nat Vital Stat Rep 53(17), 2005.

TABLE 67-2 Prevalence of Common Chronic Illnesses of Children and Adolescents

| Illness | Prevalence |

|---|---|

| PULMONARY | |

| Asthma | 8%–12 % |

| Cystic fibrosis | 1:2500 white, 1:17,000 black |

| NEUROMUSCULAR | |

| Cerebral palsy | 2–3:1000 |

| Mental retardation | 1%–2% |

| Seizure disorder | 3.5:1000 |

| Any seizure | 3%–5% |

| Auditory-visual defects | 2%–3% |

| Traumatic paralysis | 2:1000 |

| Scoliosis | 3% males, 5% females |

| Migraine | 6%–27% (↑ with increasing age) |

| ENDOCRINE/NUTRITION | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.8:1000 |

| Obesity | 25%–30% |

| Anorexia nervosa | 0.5%–1% |

| Bulimia | 1% (young adolescence), 5%–10% (19–20 yr) |

| Dysmenorrhea | 20% |

| Acne | 65% |

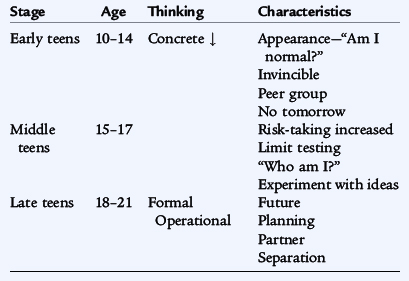

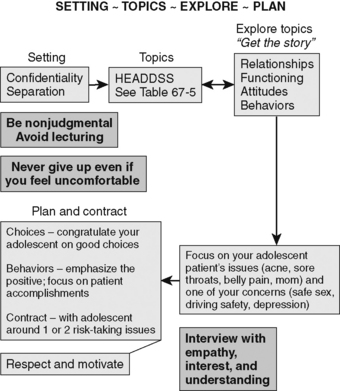

It is the physician’s responsibility to use every opportunity to inquire about risk-taking behaviors (Fig. 67-1), even when adolescents present to physicians with unrelated acute medical illnesses (e.g., sprained ankle, sore throat.) Physical symptoms in adolescents are often related to psychosocial problems.

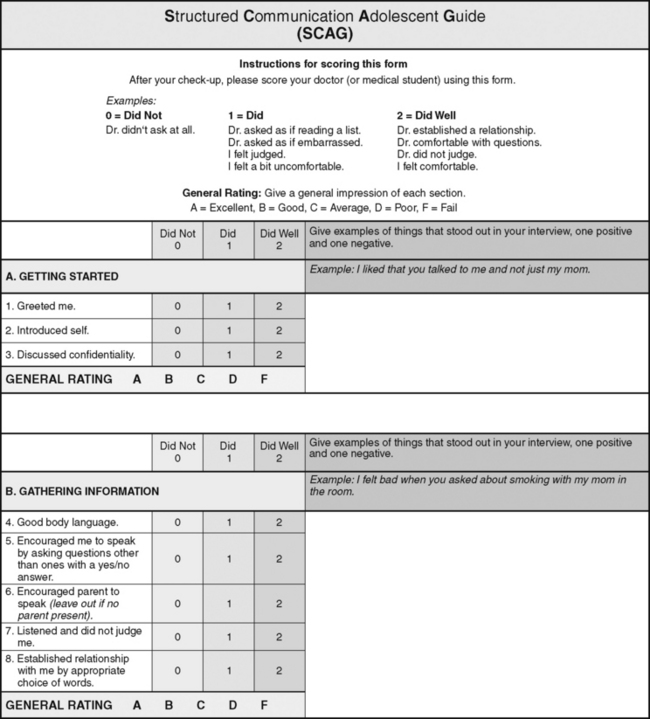

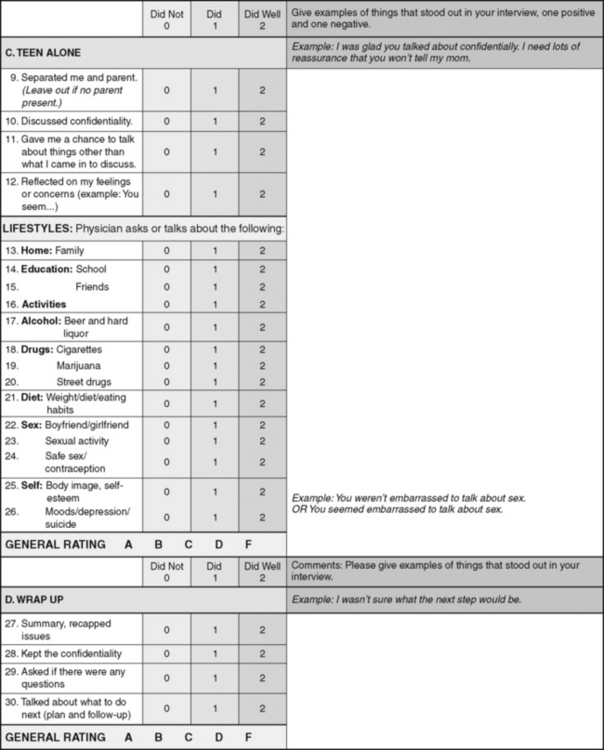

Figure 67-1 The Structured Communication Adolescent Guide (SCAG). The SCAG is an interviewing tool developed for learners to use with real or standardized adolescent patients. It incorporates the four major interview components: confidentiality, separation of the adolescent from the adult, psychosocial data gathering (using the HEADDSS mnemonic), and a nonjudgmental approach. The SCAG is at a grade 5 reading level and has demonstrated reliability and validity. A printable version is available through MedEdPORTAL.

INTERVIEWING ADOLESCENTS

The adolescent interview differs through a shift of information gathering from the parent to the adolescent. Interviewing an adolescent alone and discussing confidentiality are the cornerstones of obtaining information regarding adolescent risk-taking behaviors and anticipatory guidance (see Chapters 7 and 9).

The interview should take into account the developmental age of the adolescent (Table 67-3). However, conversations about sports, friends, movies, and activities outside school can be useful for all ages and help develop a rapport (Fig. 67-2).

Confidentiality is a key element when interviewing an adolescent (Table 67-4). It is vital to engage the adolescent in an open discussion about risk-taking behavior, and this is more likely to happen when the adolescent is alone. Some issues cannot be kept confidential, such as suicidal intent, a positive human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test (a duty to warn third parties), and disclosure of sexual or physical abuse. If there is an ambiguous situation, it is wise to obtain legal, ethical, or social worker consultation. When caring for a young adolescent, the health care provider should encourage open discussions with a parent, guardian, or other adult. Adolescents seek health care intermittently, and therefore it is important to take these opportunities to interview adolescents alone and discuss risk-taking issues (Table 67-5).

TABLE 67-4 Guidelines for Confidentiality

Prepare the preadolescent and parent for confidentiality and being interviewed alone.

Discuss confidentiality at start of the interview.

Conversations with parents/guardians/adolescent are confidential (with exceptions*).

Reaffirm confidentiality when alone with your adolescent patient.

* Exceptions to confidentiality include major or impending harm to any person (i.e., abuse, suicide, homicide).

TABLE 67-5 Interviewing the Adolescent Alone: Discussion of HEADDSS Topics*

| HOME/friends | Family, relationships, and activities. “What do you do for fun?” |

| EDUCATION | “What do you like best at school?” “How’s school going?” |

| ALCOHOL | “Are any of your friends drinking?” “Are you drinking?” |

| DRUGS | Cigarettes, marijuana, street drugs. “Have you ever smoked?” “Many adolescents experiment with different drugs and substances…. have you tried anything?” |

| DIET* | Weight, diet/eating habits. “Many adolescents worry about their weight and try dieting. Have you ever done this?” |

| SEX | Sexual activity, contraception. “Are you going out with anybody?” “Have you dated in the past?” |

| SUICIDE/DEPRESSION | Mood swings, depression, suicide attempts or thoughts, self-image. “Feeling down or depressed is common for everyone. Have you ever felt so bad that you wanted to harm yourself?” |

* The acronym HEADDSS can represent other terms, i.e., A = Activities, D = Depression. Also see Figure 67-1.

The law confers certain rights on adolescents, depending on their health condition and personal characteristics, allowing them to receive health services without parental permission (Table 67-6). Usually adolescents can seek health care without parental consent for reproductive, mental, and emergency health services. Emancipated adolescents and mature minors may be treated without parental consent; such status should be documented in the record. The key characteristics of mature minors are their competence and capacity to understand, not their chronologic age. There must be a reasonable judgment that the health intervention is in the best interests of the minor.

TABLE 67-6 Legal Rights of Minors

Age of majority (≥18 years of age in most states)

Exceptions in which health care services can be provided to a minor*

Emergency care (e.g., life-threatening condition or condition in which a delay in treatment would increase significantly the likelihood of morbidity)

Diagnosis and treatment of sexuality-related health care

Diagnosis and treatment of drug-related health care

Emancipated minors (physically and financially independent of family; Armed Forces; married; childbirth)

Mature minors (able to comprehend the risks and benefits of evaluation and treatment)

All exceptions should be documented clearly in the patient’s health record.

During the physical examination, a choice between the parent or a chaperone being present needs to be offered.

PHYSICAL GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT OF ADOLESCENTS

Girls

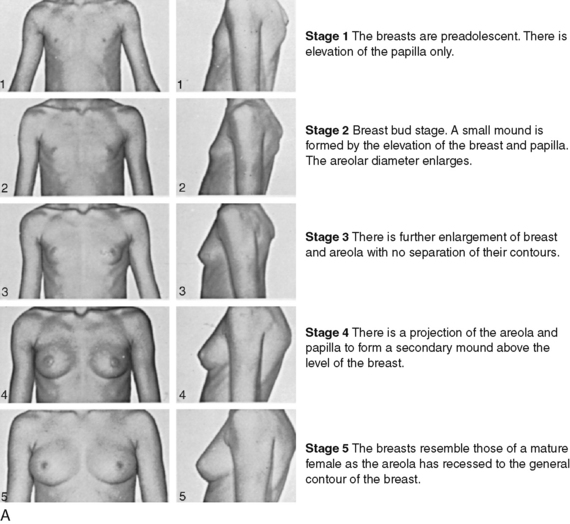

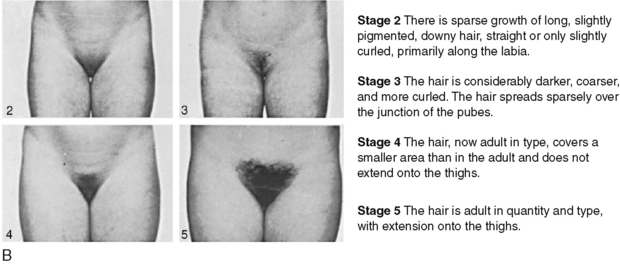

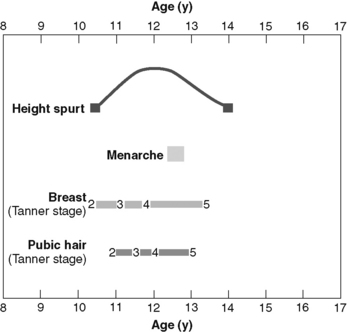

Breast budding under the areola (thelarche) and pubertal fine straight pubic hair over the mons pubis (adrenarche or pubarche) are early pubertal changes occurring around 11 years of age (range, 8 to 13 years) (see Chapter 174). These changes mark the sexual maturity rating, or Tanner stage, II of pubertal development (Figs. 67-3 and 67-4). Completion of the Tanner stages should take 4 to 5 years. The peak growth spurt usually occurs approximately 1 year after thelarche at sexual maturity rating stage III to IV breast development and before the onset of menstruation (menarche). Menarche is a relatively late pubertal event. Females grow only 2 to 5 cm in height before menarche (see Chapter 174).

Figure 67-3 Typical progression of female pubertal development, stages 1 to 5. A, Pubertal development in size of female breasts. B, Pubertal development of female pubic hair. Note that in stage 1 (not shown) there is no pubic hair.

(Courtesy of J.M. Tanner, MD, Institute of Child Health, Department of Growth and Development, University of London, London, England.)

Figure 67-4 Sequence of pubertal events in the average American female. More recent studies suggest that onset of breast development may be 9 years of age for African-American girls and 10 years of age for white girls.

(Adapted from Brookman RR, Rauh JL, Morrison JA, et al: The Princeton maturation study. 1976, unpublished data for adolescents in Cincinnati, Ohio. Reprinted from Assessment of Pubertal Development. Columbus, Ohio, Ross Laboratories, 1986.)

The mean ages of thelarche and adrenarche are approximately 9 and 10 years for African-American and white girls, respectively. The mean ages of menarche are 12.2 and 12.9 years for African-American and white girls, respectively. The interval from the initiation of thelarche to the onset of menses (menarche) is 2.3 ± 1 years. Pubertal changes before 6 years of age in African-American and 7 years of age in white girls is considered precocious.

Boys

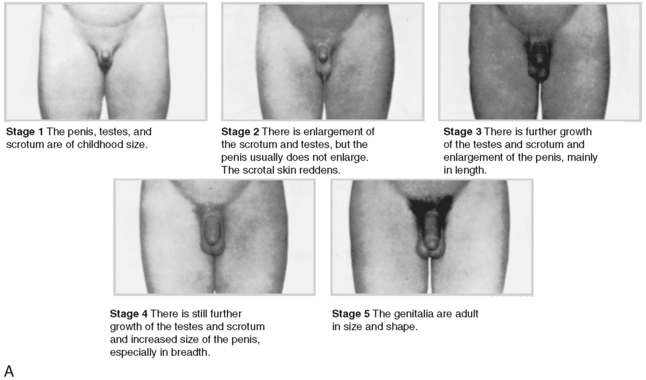

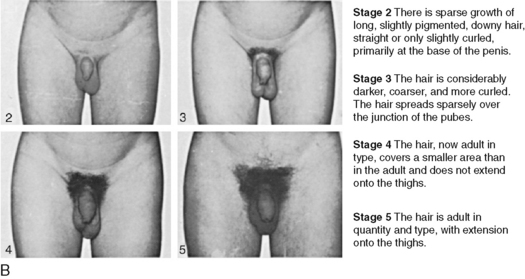

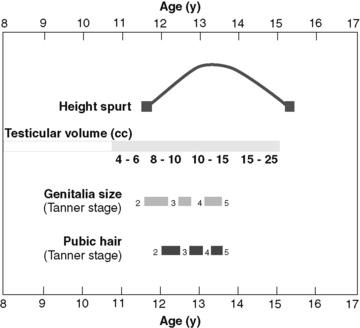

Testicular enlargement (≥2.5 cm) corresponds to sexual maturity rating, or Tanner, stage I to II (Figs. 67-5 and 67-6). Testicular enlargement is followed by pubic hair development at the base of the penis (adrenarche) and then axillary hair within the year. The growth spurt is a relatively late event; it can occur from 10.5 years of age to 16 years of age. Deepening of the voice, facial hair, and acne indicate the early stages of puberty. See Chapter 174 for discussion of disorders of puberty.

Figure 67-5 Typical progression of male pubertal development. A, Pubertal development in size of male genitalia. B, Pubertal development of male pubic hair. Note that in stage 1 there is no pubic hair.

(Courtesy of J.M. Tanner, MD, Institute of Child Health, Department of Growth and Development, University of London, London, England.)

Figure 67-6 Sequence of pubertal events in the average American male. Testicular volume less than 4 mL using orchidometer (Prader Beads) represents prepubertal stage.

(Adapted from Brookman RR, Rauh JL, Morrison JA, et al: The Princeton maturation study. 1976, unpublished data for adolescents in Cincinnati, Ohio. Reprinted from Assessment of Pubertal Development. Columbus, Ohio, Ross Laboratories, 1986.)

Changes Associated with Physical Maturation

Tanner stages mark biologic maturation that can be related to specific laboratory value changes and certain physical conditions. The higher hematocrit values in adolescent boys than in adolescent girls are the result of greater androgenic stimulation of the bone marrow and not loss through menstruation. Alkaline phosphatase levels in boys and girls increase during puberty because of rapid bone turnover, especially during the growth spurt. Worsening of mild scoliosis is common in adolescents during their growth spurt.

SEE

SEE