CHAPTER 9 Evaluation of the Well Child

CHAPTER 9 Evaluation of the Well Child

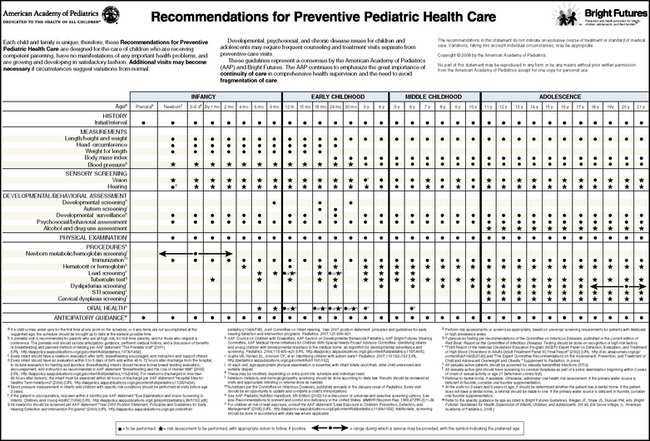

Health maintenance or supervision visits should consist of a comprehensive assessment of the child’s health and of the parent’s/guardian’s role in providing an environment for optimal growth, development, and health. Bright Futures standardizes each of the health maintenance visits and provides resources for working with the children and families of different ages (http://brightfutures.aap.org). Elements of each visit include evaluation and management of parental concerns; inquiry about any interval illness since the last physical, growth, development, and nutrition; anticipatory guidance (including safety information and counseling); physical examination; screening tests; and immunizations (Table 9-1). Figure 9-1 indicates the ages that specific prevention measures should be undertaken (by testing, such as vision and hearing; by physician history and physical examination; or by laboratory screening, such as the neonatal metabolic screening test or lead screening).

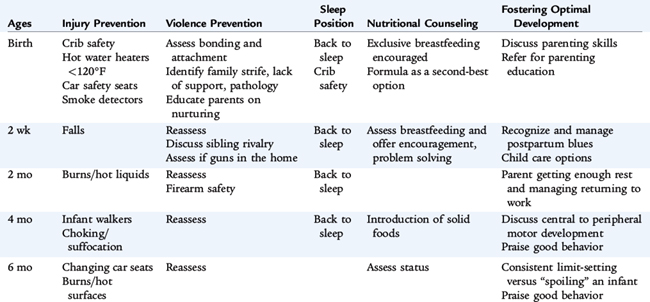

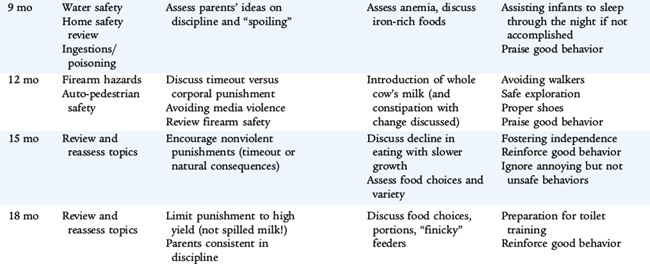

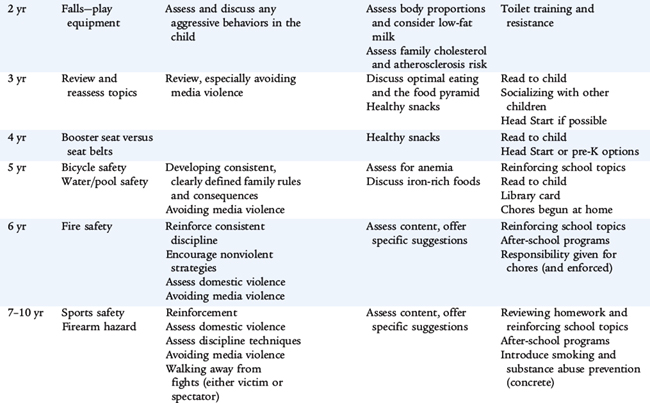

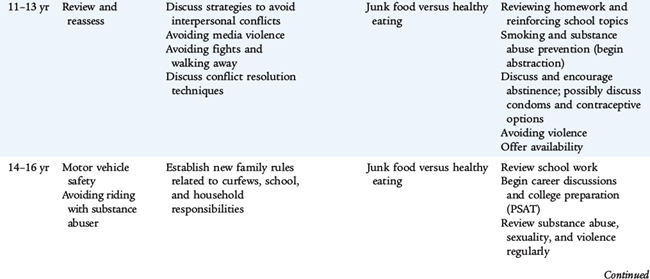

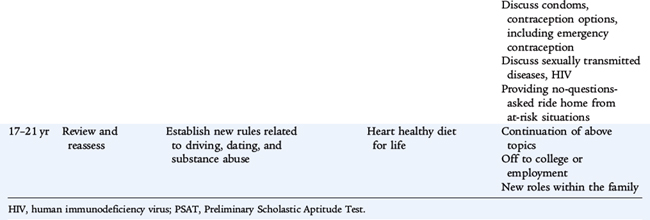

TABLE 9-1 Topics for Health Supervision Visits

FOCUS ON THE CHILD

FOCUS ON THE CHILD’S ENVIRONMENT

Family

Community

Physical Environment

Figure 9-1 Recommendations for preventive pediatric health care.

(From the Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine: Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care, Pediatrics 120(6): 1376, 2007.)

SCREENING TESTS

Children usually are quite healthy, especially after 1 year of age, and only the following screening tests are recommended: newborn metabolic screening with hemoglobin electrophoresis, hearing and vision evaluation, anemia and lead screening, and tuberculosis testing. Children born to families with dyslipidemias or early heart disease also may be screened for lipid disorders. (Items marked by a star in Figure 9-1 should be performed if a risk factor is found.) Sexually experienced adolescents should be screened for sexually transmissible infections. When an infant or child begins care after the newborn period, the pediatric provider should perform any missing screening tests and immunizations.

Newborn Screening

Metabolic Screening

Every state in the United States mandates newborn metabolic screening. Phenylketonuria (PKU) is the prototypic illness to be screened for and prevented. However, if PKU is detected early, a modified diet (a highly specialized phenylalanine-free formula) can be provided, and the disease-related developmental and growth problems can be prevented. Each state determines its own priorities and procedures, but the following diseases are usually included in metabolic screening: PKU, galactosemia, congenital hypothyroidism, and maple sugar urine disease (see Section 10). Many states have instituted screening programs for cystic fibrosis using a screening test of immunoreactive trypsinogen (IRT). If that test is positive, then DNA analysis for cystic fibrosis mutations is performed.

Hemoglobin Electrophoresis

Children with hemoglobinopathies are at higher risk for infection and complications from anemia. Early detection may prevent or ameliorate these complications. Infants with sickle cell disease are begun on oral penicillin prophylaxis to prevent sepsis, the major cause of mortality in these infants (see Chapter 150).

Hearing Evaluation

Because speech and language are central to a child’s cognitive development, hearing screening is performed before discharge from the newborn nursery. An infant’s hearing is tested by placing headphones over the infant’s ears and electrodes on the head. Standard sounds are played, and the transmission of the impulse to the brain is documented. If this screening test is abnormal, a further evaluation is indicated, using evoked response technology of sound transmission, similar to an electroencephalogram.

Hearing and Vision Screening of Older Children

Infants and Toddlers

Inferences about hearing are drawn from asking parents about responses to sound and speech and by examining speech and language development closely. Inferences about vision may be made by examining gross motor milestones (children with vision problems may have a delay) and by physical examination of the eye. Parents should be queried as to any concerns about vision until the child is 3 years of age and about hearing until the child is 4 years of age. If there are concerns, definitive testing should be arranged. Hearing can be screened by auditory evoked responses as mentioned for infants. For toddlers and older children who cannot cooperate with formal audiologic testing with headphones, behavioral audiology may be used. Sounds of a specific frequency or intensity are provided in a standard environment within a soundproof room, and responses are assessed by a trained audiologist. Vision may be assessed by referral to a pediatric ophthalmologist and by visual evoked responses.

Children 3 Years of Age and Older

At various ages, hearing and vision should be screened objectively using standard techniques. In Figure 9-1, any age marked O requires objective screening and S denotes that a subjective assessment is adequate at that age. Asking the family and child about any concerns or consequences of poor hearing or vision accomplishes subjective evaluation. At 3 years of age, children are screened for vision for the first time if they are developmentally able to be tested. Many children at this age do not have the interactive language or interpersonal skills to perform a vision screen; these children should be re-examined at a 3- to 6-month interval to ensure that vision is normal. Because most of these children do not identify letters yet, using a Snellen eye chart with standard shapes is recommended. When a child is able to identify letters, the more accurate letter-based chart should be used. Audiologic testing of sounds with headphones and children identifying sounds heard should be begun on the fourth birthday (although Head Start requires that pediatricians attempt hearing screening at 3 years of age). Any suspected audiologic problem should be evaluated by a careful history and physical examination, and the child should be referred for comprehensive testing. Children who have a documented vision problem, failed screening, or parental concern should be referred, preferably to a pediatric ophthalmologist. However, many communities do not have access, so a general ophthalmologist is consulted.

Anemia Screening

After the newborn period, when hemoglobin electrophoresis is used to detect inherited abnormalities, children are screened for anemia at ages when there is a higher incidence of iron deficiency anemia. Anemic infants do not perform as well on standard developmental testing. Infants are screened at birth and again at 4 months if there is a documented risk, such as low birth weight or prematurity. Healthy term infants usually are screened at 12 months of age because this is when a high incidence of iron deficiency is noted. Children are assessed at other visits for risks or concerns related to anemia (denoted by a star in Fig. 9-1). Any abnormalities detected should be evaluated for etiology. When iron deficiency is strongly suspected, a therapeutic trial of iron may be used (see Chapter 150).

Lead Screening

Lead intoxication may cause developmental and behavioral abnormalities that are not reversible even if the hematologic and other metabolic complications are treated. Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends environmental investigation at blood lead levels of 20 μg/dL on a single visit or persistent 15 μg/dL over a 3-month period, levels of 5 to 10 μg/dL may cause learning problems. Risk factors for lead intoxication include living in older homes with cracked or peeling lead-based paint, industrial exposure, use of foreign remedies (e.g., a diarrhea remedy from Mexico), and use of pottery with lead paint glaze. Because of the significant association of lead intoxication with poverty and the numerous children living in poverty, the CDC recommends blood lead screening at 12 and 24 months. In addition, standardized screening questions for risk of lead intoxication should be asked for all children between 6 months and 6 years of age (Table 9-2). Any positive or suspect response is an indication for obtaining a blood lead level. Because capillary blood sampling may produce false-positive results, a venous blood sample should be obtained. County health departments and private companies provide lead inspection and detection services to determine the source of the lead. Standard decontamination techniques should be used to remove the lead while avoiding aerosolizing the toxic metal that a child might breathe or creating dust that a child might ingest (see Chapters 149 and 150).

TABLE 9-2 Lead Poisoning Risk Assessment Questions to Be Asked Between 6 Months and 6 Years

Tuberculosis Testing

The prevalence of tuberculosis is increasing, largely as a result of the adult human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic, and children often present with serious and multisystem disease (miliary tuberculosis). All children should be assessed for tuberculosis at health maintenance visits, especially after 1 year of age. The high-risk groups, as defined by the CDC, are listed in Table 9-3. In general, the standardized purified protein derivative (PPD) intradermal test is used. Because parents may misinterpret the test, a health care provider must evaluate the test 48 to 72 hours after injection. The size of induration, not the color of any mark, denotes a positive test. For most patients, 10 mm of induration is a positive test. For HIV-positive patients, those with recent tuberculosis contacts, patients with evidence of old healed tuberculosis on chest film, or immunosuppressed patients, 5 mm is a positive test (see Chapter 124). The CDC has approved (in adults) the QuantiFERON-TB Gold Test, which has the advantage of needing only one office visit.

TABLE 9-3 Groups at High Risk for Tuberculosis

Cholesterol

Children and adolescents who have a family history of cardiovascular disease or have at least one parent with a high blood cholesterol level are at increased risk of having high blood cholesterol levels as adults and increased risk of coronary heart disease. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends dyslipidemia screening in the context of regular health care for at-risk populations (Table 9-4) by a fasting lipid profile. The recommended screening levels are the same for all children 2 to 18 years. Total cholesterol of less than 170 mg/dL is normal, 170 to 199 mg/dL is borderline, greater than 200 mg/dL is elevated.

Sexually Transmitted Infection Testing

Annual office visits are recommended for adolescents, at least in ones older than 12 years of age. A full adolescent psychosocial history should be obtained in confidential fashion, with the parent excused from the examination room and confidential matters discussed. Part of this evaluation is a comprehensive sexual history. Often adolescents must be questioned creatively to elicit information on sexual activity. Not all adolescents identify oral sex as sex, and some adolescents misinterpret the term sexually active to mean that one has many sexual partners or is very vigorous during intercourse. The questions “Are you having sex?” and “Have you ever had sex?” should be asked. Any child or adolescent who has had any form of sexual intercourse should have at least an annual evaluation (more often if there is a history of high-risk sex) for sexually transmitted diseases by physical examination (genital warts, genital herpes, and pediculosis) and laboratory testing (chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and HIV) (see Chapter 116). Adolescent girls should be assessed for human papillomavirus and precancerous lesions by Papanicolaou smear 3 years after beginning vaginal intercourse or at 21 years of age.

IMMUNIZATIONS

Immunization records should be checked at each office visit, regardless of the reason. Appropriate vaccinations should be administered (see Chapter 94).

DENTAL CARE

Many families in the United States, particularly poor families and ethnic minorities, underuse dental health care. Pediatricians may identify gross abnormalities, such as large caries, gingival inflammation, or significant malocclusion. All children should have a dental examination by a dentist at least annually and a dental cleaning by a dentist or hygienist every 6 months. Dental health care visits should include instruction about preventive care practiced at home (brushing and flossing). Other prophylactic methods shown to be effective at preventing caries are fluoride topical treatments and acrylic sealants on the molars provided by dentists. Pediatric dentists recommend beginning visits at age 1 year to educate families and to screen for milk bottle caries. Some recommend that pediatricians apply dental varnish to the children’s teeth, especially in communities that do not have pediatric dentists. Fluoridation of water or fluoride supplements in communities that do not have fluoridation is important in prevention of cavities (see Chapter 127).

NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT

Plotting a child’s growth on the standard charts is a vital component of the nutritional assessment. A dietary history should be obtained because the content of the diet may suggest a risk of nutritional deficiency (see Chapters 27 and 28).

ANTICIPATORY GUIDANCE

Anticipatory guidance is information conveyed to parents verbally or in written materials (or even directing parents to certain websites on the Internet) that is meant to assist them in facilitating optimal growth and development for their children. Figure 9-1 calls for discussions in four areas: injury prevention, violence prevention, sleep position counseling (until 6 months of age), and nutrition counseling. Table 9-5 summarizes representative issues that might be discussed within the four areas and a fifth area, fostering optimal development and behavior. It is important to review briefly the safety topics previously discussed at other visits for reinforcement. Age-appropriate discussions should occur at each visit. Bright Futures is an AAP project to standardize and improve issues in anticipatory guidance for pediatricians and other health care providers (see http://brightfutures.aap.org).

Safety Issues

The most common cause of death for infants 1 month to 1 year of age is motor vehicle crashes. No newborn should be discharged from a nursery unless the parents have a functioning and properly installed car seat. Many automobile dealerships offer services to parents to ensure that safety seats are installed properly in their specific model. Most states have laws that mandate safety seats until the child reaches 4 years of age or 40 pounds in weight or even heavier. Repeat offenses may lead to suspension of driving privileges. The following are age-appropriate recommendations for car safety.

The Back to Sleep initiative has reduced the incidence of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Before the initiative, infants routinely were placed prone to sleep. Since 1992, when the AAP recommended this program, the annual SIDS rate has decreased by more than 50%. Another initiative is aimed at day care providers, because 20% of SIDS deaths occur in day care settings.

Fostering Optimal Development

See Figure 9-1 and Table 9-5 for presentation of age-appropriate activities that the pediatrician may advocate for families.

Discipline means to teach, not merely to punish. The ultimate goal is the child’s self-control. Overbearing punishment to control a child’s behavior interferes with the learning process and focuses on external control at the expense of the development of self-control. Parents who set too few reasonable limits may be frustrated by children who cannot control their own behavior. Discipline should teach a child exactly what is expected by supporting positive behaviors and responding appropriately to negative behaviors with proper limits. It is more important to reinforce good behavior than to punish bad behavior.

Commonly used techniques to control undesirable behaviors in children include scolding, physical punishment, and threats. These techniques have potential adverse effects on children’s sense of security and self-esteem. The effectiveness of scolding diminishes the more it is used. Scolding should not be allowed to expand from an expression of displeasure about a specific event to derogatory statements about the child. Scolding also may escalate to the level of psychological abuse. It is important to educate parents that they have a good child who does bad things from time to time, so parents do not think and tell the child that he or she is “bad.”

Frequent mild physical punishment (corporal punishment) may become less effective over time and tempt the parent to escalate the physical punishment, increasing the risk of child abuse. Corporal punishment teaches a child that in certain situations it is proper to strike another person. Commonly, in households that use spanking, older children who have been raised with this technique are seen responding to younger sibling behavioral problems by hitting their siblings.

Threats by parents to leave or to give up the child are perhaps the most psychologically damaging ways to control a child’s behavior. Children of any age may remain fearful and anxious about loss of the parent long after the threat is made; however, many children are able to see through empty threats. Threatening a mild loss of privileges (no video games for 1 week or grounding a teenager) may be appropriate, but the consequence must be enforced if there is a violation.

Parenting involves a dynamic balance between setting limits on the one hand and allowing and encouraging freedom of expression and exploration on the other. A child whose behavior is out of control improves when clear limits on their behavior are set and enforced. Children find comfort and security in clear limits. However, parents must agree on where the limit will be set and how it will be enforced. The limit and the consequence of breaking the limit must be clearly presented to the child. Enforcement of the limit should be consistent and firm. Too many limits are difficult to learn and may thwart the normal development of autonomy. The limit must be reasonable in terms of the child’s age, temperament, and developmental level. To be effective, both parents (and other adults in the home) must enforce limits. Otherwise, children may effectively split the parents and seek to test the limits with the more indulgent parent. In all situations, to be effective, punishment must be brief and linked directly to a behavior. More effective behavioral change occurs when punishment also is linked to praise of the intended behavior.

Extinction is an effective and systematic way to eliminate a frequent, annoying, and relatively harmless behavior by ignoring it. First, parents should note the frequency of the behavior to appreciate realistically the magnitude of the problem and to evaluate progress. It also is important to help parents determine what reinforces the child’s behavior and what needs to be consistently eliminated. An appropriate behavior is identified to give the child a positive alternative that the parents can reinforce. Parents should be warned that the annoying behavior usually increases in frequency and intensity (and may last for weeks) before it decreases when the parent ignores it (removes the reinforcement). A child who has an attention-seeking temper tantrum should be ignored or placed in a secure environment. This action may anger the child more, and the behavior may get louder and angrier. Eventually, as the child realizes that there is no audience for the tantrum, the tantrums decrease in intensity and frequency. In each specific instance, when the child has begun to play with a favorite toy in a quiet and appropriate fashion, he or she should be praised, and extra attention should be given. This is an effective technique for early toddlers, before their capacity to understand and adhere to a timeout.

The timeout consists of a short period of isolation immediately after a problem behavior is observed. Timeout interrupts the behavior and immediately links it to an unpleasant consequence. This method requires considerable effort by the parents because the child does not wish to be isolated. A parent may need to hold the child physically in timeout. In this situation, the parent should become part of the furniture and should not respond to the child until the timeout period is over. When established, a simple isolation technique, such as making a child stand in the corner or sending a child to his or her room, may be effective. If such a technique is not helpful, a more systematic procedure may be needed. One effective protocol for the timeout procedure involves interrupting the child’s play when the behavior occurs and having the child sit in a dull, isolated place for a brief period, measured by a portable kitchen timer (kitchen timers are valuable because the clicking noises document that time is passing and the bell alarm at the end signals the end of the punishment; this obviates responding to the inevitable question, “Is time up yet?”) Timeout is simply punishment and is not a time for a young child to think about the behavior (because these children do not possess the capacity for abstract thinking) or a time to de-escalate the behavior. The amount of timeout should be appropriate to the child’s short attention span. One minute per year of a child’s age is recommended. This inescapable and unpleasant consequence of the undesired behavior motivates the child to learn to avoid the behavior.