CHAPTER 70 Eating Disorders

CHAPTER 70 Eating Disorders

Eating disorders are common chronic diseases in adolescents, especially in females. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV), classifies these psychiatric illnesses as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder (compulsive eating), and eating disorder not otherwise specified. The diagnosis in young adolescents (pre–growth spurt, premenstrual) may not follow the classic DSM IV–diagnostic criteria. The normal developmental milestones of adolescence may be triggers for eating disorders (Table 70-1).

TABLE 70-1 Normal Adolescent Milestones

| Psychological Stages | Issues That Can Trigger Eating Disorders |

|---|---|

| Early adolescence—increased body awareness | Fear of growing up |

| Middle adolescence—increased self-awareness | Rebelliousness |

| Competition and achievement | |

| Late adolescence—identity | Anxiety and worry for the future |

| Need for control |

ANOREXIA NERVOSA

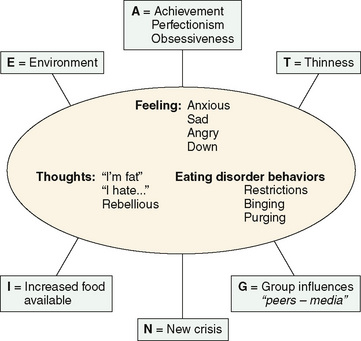

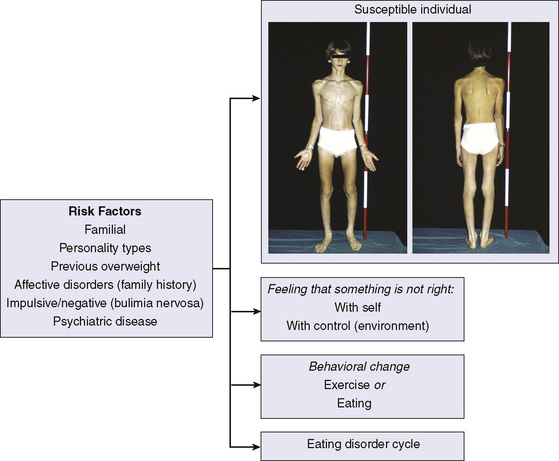

The prevalence of anorexia nervosa is 1.5% in teenage girls. The female-to-male ratio is approximately 20:1, and the condition shows a familial pattern. The cause of anorexia nervosa is unknown, but it involves a complex interaction between social, environmental, psychological, and biologic events (Fig. 70-1). Risk factors have been identified (Fig. 70-2).

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

It is important to screen early for eating disorders. Screening is best done as a part of the larger psychosocial screen for risk-taking factors (see Fig. 67-1). It is recommended that the adolescent be interviewed alone. An adolescent with an eating disorder may minimize the problem. So interviewing the parent(s) alone is also important, the first event that a patient with anorexia or bulimia usually describes is a behavioral change in eating or exercise (food obsession, food-related ruminations, mood changes). The patient has an unrealistic body image and feels too fat despite appearing excessively thin. Parents’ response to this situation can be anger, self-blame, focusing attention on the child, ignoring the disorder, or approving of the behavior.

The physician should be nonjudgmental, collect information, and work on a differential diagnosis. The differential diagnosis of weight loss includes gastroesophageal reflux, peptic ulcer, malignancy, chronic diarrhea, malabsorption, inflammatory bowel disease, increased energy demands, hypothalamic lesions, hyperthyroidism, diabetes mellitus, and Addison disease. Psychiatric disorders also need to be considered (drug abuse, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorders).

The clinical features of anorexia include the patient wearing oversized layered clothing to hide appearance, fine hair on the face and trunk (lanugo-like hair), rough and scaly skin, bradycardia, hypothermia, decreased body mass index, erosion of enamel of teeth (acid from emesis), and acrocyanosis of hands and feet. Signs of hyperthyroidism should not be present (see Chapter 175). The diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa are listed in Table 70-2.

TABLE 70-2 Diagnostic Criteria for Anorexia Nervosa

Refusal to maintain body weight at or above a minimally normal weight for age and height (e.g., weight loss leading to body weight <85% of ideal)*

Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, even though underweight

Denial of the seriousness of the low body weight—a disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced

Amenorrhea in postmenarche females*

* The diagnostic criteria may be difficult to meet in a young adolescent. Allow for a wide spectrum of clinical features.

Treatment and Prognosis

Treatment requires a multidisciplinary approach consisting of a feeding program as well as individual and family therapy. Feeding is accomplished through voluntary intake of regular foods or of a nutritional formula orally or by nasogastric tube. When vital signs are stable, discussion and negotiation of a detailed treatment contract with the patient and the parents are essential. The first step is to restore body weight. Hospitalization may be necessary (Table 70-3). When 80% of normal weight is achieved, the patient is given freedom to gain weight at a personal pace. The prognosis includes a 3% to 5% mortality (suicide, malnutrition) rate, the development of bulimic symptoms (30% of individuals), and persistent anorexia nervosa syndrome (20% of individuals).

TABLE 70-3 When to Hospitalize an Anorexic Patient

Weight loss >25% ideal body weight*

Risk of suicide

Bradycardia, hypothermia

Dehydration, hypokalemia, dysrhythmias

Outpatient treatment fails

BULIMIA NERVOSA

Table 70-4 presents the diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa. The prevalence of bulimia nervosa is 5% in female college students. The female-to-male ratio is 10:1. Binge-eating episodes consist of large quantities of often forbidden foods or leftovers or both, consumed rapidly, followed by vomiting. Metabolic abnormalities result from the excessive vomiting or laxative and diuretic intake. Binge-eating episodes and the loss of control over eating often occur in young women who are slightly overweight with a history of dieting.

TABLE 70-4 Diagnostic Criteria for Bulimia Nervosa

Nutritional, educational, and self-monitoring techniques are used to increase awareness of the maladaptive behavior, following which efforts are made to change the eating behavior. Patients with bulimia nervosa may respond to antidepressant therapy because they often have personality disturbances, impulse control difficulties, and family histories of affective disorders. Patients feel embarrassed, guilty, and ashamed of their actions. Attempted suicide and completed suicide (5%) are an important concern.