CHAPTER 96 Fever without a Focus

CHAPTER 96 Fever without a Focus

Core body temperature is normally maintained within 1° C to 1.5° C in a range of 37° C to 38° C. Normal body temperature is generally considered to be 37° C (98.6° F; range, 97° F to 99.6° F). There is a normal diurnal variation, with maximum temperature in the late afternoon. Rectal temperatures higher than 38° C (>100.4° F) generally are considered abnormal, especially if associated with symptoms.

Normal body temperature is maintained by a complex regulatory system in the anterior hypothalamus. Development of fever begins with release of endogenous pyrogens into the circulation as the result of infection, inflammatory processes, or malignancy. Microbes and microbial toxins act as exogenous pyrogens by stimulating release of endogenous pyrogens, including cytokines such as interleukin-1, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor, and interferons. These cytokines reach the anterior hypothalamus, liberating arachidonic acid, which is metabolized to prostaglandin E2. Elevation of the hypothalamic thermostat occurs via a complex interaction of complement and prostaglandin-E2 production. Antipyretics (acetaminophen, ibuprofen, aspirin) inhibit hypothalamic cyclooxygenase, decreasing production of prostaglandin E2. Aspirin is associated with Reye syndrome in children and is not recommended as an antipyretic. The response to antipyretics does not distinguish bacterial from viral infections.

The pattern of fever in children may vary depending on the age of the child and the nature of the illness. Neonates may not have a febrile response and may be hypothermic despite significant infection, whereas older infants and children younger than 5 years of age may have an exaggerated febrile response with temperatures of up to 105° F (40.6° C) in response to either a serious bacterial infection or an otherwise benign viral infection. Fever to this degree is unusual in older children and adolescents and suggests a serious process. The fever pattern does not reliably distinguish fever caused by bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic organisms from that resulting from malignancy, autoimmune diseases, or drugs.

Children with fever without a focus present a diagnostic challenge that includes identifying bacteremia and sepsis. Bacteremia, a positive blood culture, may be primary or secondary to a focal infection. Sepsis is the systemic response to infection that is manifested by hyperthermia or hypothermia, tachycardia, tachypnea, and shock (see Chapter 40). Children with septicemia and signs of central nervous system dysfunction (irritability, lethargy), cardiovascular impairment (cyanosis, poor perfusion), and disseminated intravascular coagulation (petechiae, ecchymosis) are readily recognized as toxic appearing or septic. Most febrile illness in children may be categorized as follows:

FEVER IN INFANTS YOUNGER THAN 3 MONTHS OF AGE

Fever or temperature instability in infants younger than 3 months of age is associated with a higher risk of serious bacterial infections than in older infants. These younger infants usually exhibit only fever and poor feeding, without localizing signs of infection. Most febrile illnesses in this age group are caused by common viral pathogens, but serious bacterial infections include bacteremia (caused by group B streptococcus, Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes in neonates; and Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, nontyphoidal Salmonella, Neisseria meningitidis in 1 to 3-month-old infants), urinary tract infection (UTI) (E. coli), pneumonia (Staphylococcus aureus, S. pneumoniae, or group B streptococcus), meningitis (S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae type b, group B streptococcus, meningococcus, herpes simplex virus, enteroviruses), bacterial diarrhea (Salmonella, Shigella, E. coli), and osteomyelitis or suppurative arthritis (septic arthritis) (S. aureus or group B streptococcus).

Differentiation between viral and bacterial infections in young infants is difficult. Febrile infants younger than 3 months of age who appear ill, especially if follow-up is uncertain, and all febrile infants younger than 4 weeks of age should be admitted to the hospital for empirical antibiotics pending culture results. After blood, urine, and cerebrospinal cultures are obtained, broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics (cefotaxime and ampicillin or ampicillin and gentamicin) are administered. The choice of antibiotics depends on the pathogens suggested by localizing findings. Well-appearing febrile infants 4 weeks of age and older without an identifiable focus and with certainty of follow-up are at a low risk of developing a serious bacterial infection (0.8% develop bacteremia, and 2% develop a serious localized bacterial infection). Specific criteria identifying these low-risk infants include age older than 1 month, well-appearing without a focus of infection, no history of prematurity or prior antimicrobial therapy, a white blood cell (WBC) count of 5000 to 15,000/μL, urine with less than 10 WBCs/high-power field, stool with less than 5 WBCs/high-power field (obtained for infants with diarrhea), and normal chest x-ray (obtained for infants with respiratory signs). These infants may be followed as outpatients without empirical antibiotic treatment, or, alternatively, may be treated with intramuscular ceftriaxone. Regardless of antibiotic treatment, close follow-up for at least 72 hours, including re-evaluation in 24 hours or immediately with any clinical change, is essential.

FEVER IN CHILDREN 3 MONTHS TO 3 YEARS OF AGE

A common problem is the evaluation of a febrile but well-appearing child younger than 3 years of age without localizing signs of infection. Although most of these children have self-limited viral infections, some have occult bacteremia (bacteremia without identifiable focus) or UTIs, and a few have severe and potentially life-threatening illnesses. It is difficult, even for experienced clinicians, to differentiate patients with bacteremia from those with benign illnesses.

Observational assessment is a key part of the evaluation. Descriptions of normal appearance and alertness include child looking at the observer and looking around the room, with eyes that are shiny or bright. Descriptions that indicate severe impairment include glassy and stares vacantly into space. Observations such as sitting, moving arms and legs on table or lap, and sits without support reflect normal motor ability, whereas no movement in mother’s arms and lies limply on table indicate severe impairment. Normal behaviors, such as vocalizing spontaneously, playing with objects, reaching for objects, smiling, and crying with noxious stimuli, reflect playfulness; abnormal behaviors reflect irritability. A normal response of the behavior consolability of the crying child is stops crying when held by the parent, whereas severe impairment is indicated by continual cry despite being held and comforted.

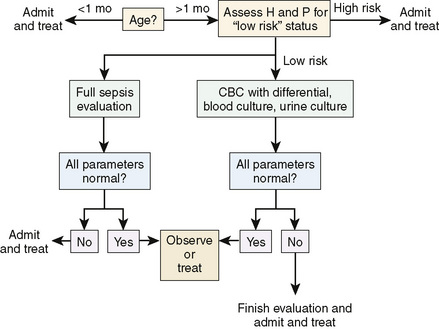

Children between 2 months and 3 years of age are at increased risk for infection with organisms with polysaccharide capsules, including S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, N. meningitidis, and nontyphoidal Salmonella. Effective phagocytosis of these organisms requires opsonic antibody. Transplacental maternal IgG initially provides immunity to these organisms, but as the IgG gradually dissipates, risk of infection increases. In the United States, use of conjugate H. influenzae type b and S. pneumoniae vaccines has dramatically reduced the incidence of these infections. Determining the immunization status of the child is essential to evaluate risk of these infections. An approach to evaluation of these children is outlined in Figure 96-1.

Figure 96-1 Approach to a child younger than 36 months of age with fever without localizing signs. The specific management varies depending on the age and clinical status of the child.

Most episodes of fever in children younger than 3 years of age have a demonstrable source of infection that is elicited by history, physical examination, or a simple laboratory test. In this age group, the most commonly identified serious bacterial infection is a UTI. A blood culture to evaluate for occult bacteremia and urinalysis and urine culture to evaluate for a UTI should be performed for all children younger than 3 years of age with fever without localizing signs. Patients with diarrhea should have a stool evaluation for leukocytes. Ill-appearing children should be admitted to the hospital and treated with antibiotics.

Approximately 0.2% of well-appearing febrile children 3 to 36 months of age without localizing signs, who have been vaccinated against S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae, have occult bacteremia. Risk factors for occult bacteremia include temperature of 102.2° F (39° C) or greater, WBC count of 15,000/mm3 or more, and elevated absolute neutrophil count, band count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or C-reactive protein. No combination of demographic (socioeconomic status, race, gender, and age), clinical parameters, or laboratory tests in these children reliably predicts occult bacteremia. Occult bacteremia in otherwise healthy children is usually transient and self-limited but may progress to serious localizing infections. Well-appearing children usually are followed as outpatients without empirical antibiotic treatment or, alternatively, treated with intramuscular ceftriaxone. Regardless of antibiotic treatment, close follow-up for at least 72 hours, including re-evaluation in 24 hours or immediately with any clinical change, is essential. Children with a positive blood culture require immediate re-evaluation, repeat blood culture, consideration for lumbar puncture, and empirical antibiotic treatment.

Children with sickle cell disease have impaired splenic function and properdin-dependent opsonization that places them at increased risk for bacteremia, especially during the first 5 years of life. Children with sickle cell disease and fever who appear seriously ill, have a temperature of 104° F (40° C) or greater, or WBC count less than 5000/mm3 or greater than 30,000/mm3 should be hospitalized and treated empirically with antibiotics. Other children with sickle cell disease and fever should have blood culture, empirical treatment with ceftriaxone, and close outpatient follow-up. Osteomyelitis resulting from Salmonella or S. aureus is more common in children with sickle cell disease; the blood culture is not always positive in the presence of osteomyelitis.

FEVER OF UNKNOWN ORIGIN

FUO is defined as temperature greater than 100.4° F (38° C) lasting for more than 14 days without an obvious cause despite a complete history, physical examination, and routine screening laboratory evaluation. Imaging and special diagnostic techniques, including imaging-guided biopsy, have decreased greatly the number of patients with FUO. It is important to distinguish persistent fever from recurrent fever, which usually represents serial acute illnesses.

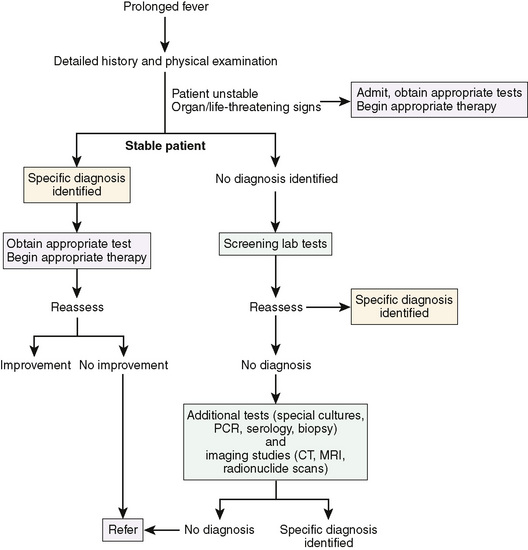

The initial evaluation of FUO requires a thorough history and physical examination supplemented with a few screening laboratory tests (Fig. 96-2). Additional laboratory and imaging tests are determined by abnormalities on initial evaluation. Important elements of the history include the impact the fever has had on the child’s health and activity; weight loss; the use of drugs, medications, or immunosuppressive therapy; history of unusual, severe, or chronic infection suggesting immunodeficiency (see Chapter 72); immunizations; exposure to unprocessed or raw foods; history of pica and exposure to soil-borne or waterborne organisms; exposure to industrial or hobby-related chemicals; blood transfusions; domestic or foreign travel; exposure to animals; exposure to ticks or mosquitoes; ethnic background; recent surgical procedures or dental work; tattooing and body piercing; and sexual activity.

Figure 96-2 Approach to the evaluation of fever of unknown origin (FUO) in children. Screening laboratory tests include a complete blood count (CBC) and differential white blood cell (WBC) count, platelet count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, hepatic transaminase levels, urinalysis, bacterial cultures of urine and blood, chest radiograph, and evaluation for rheumatic disease with antinuclear antibody (ANA), rheumatoid factor, and serum complement (C3, C4, CH50).

The etiology of most occult infections causing FUO is an unusual presentation of a common disease. Sinusitis, endocarditis, intra-abdominal abscesses (perinephric, intrahepatic, subdiaphragmatic), and central nervous system lesions (tuberculoma, cysticercosis, abscess, toxoplasmosis) may be relatively asymptomatic. Infections are the most common cause of FUO in children, followed by inflammatory diseases, malignancy, and other etiologies (Table 96-1). Inflammatory diseases account for approximately 20% of episodes. Malignancies are a less common cause of FUO in children than in adults, accounting for about 10% of all episodes. Approximately 15% of children with FUO have no diagnosis. Fever eventually resolves in many of these cases, usually without sequelae, although some may develop definable signs of rheumatic disease over time.

TABLE 96-1 Causes of Fever of Unknown Origin in Children

INFECTIONS

Localized infections

Bacterial Diseases

Viral Diseases

Chlamydial Diseases

Rickettsial Diseases

Fungal Diseases

Parasitic Diseases

INFLAMMATORY DISEASES

MALIGNANCIES

MISCELLANEOUS

Modified from Powell KR: Fever without a focus. In Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, et al: Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 18th ed, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders.

FUO also may be the presentation of an immunodeficiency disease. A history of unusual, severe, or chronic infections suggests immunodeficiency (see Chapter 72) and requires an aggressive evaluation to identify occult infections. Common infections causing FUO in these patients include viral hepatitis, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, Bartonella henselae, ehrlichiosis, Salmonella, and tuberculosis.

Factitious fever or fever produced or feigned intentionally by the patient (Munchausen syndrome) or the parent of a child (Munchausen syndrome by proxy) is an important consideration, particularly if family members are familiar with health care practices (see Chapter 22). Fever should be recorded in the hospital by a reliable individual who remains with the patient when the temperature is taken. Continuous observation over a long period and repetitive evaluation are essential.

Screening tests for FUO include complete blood count with WBC and differential count, platelet count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, hepatic transaminase levels, urinalysis, cultures of urine and blood, chest radiograph, and evaluation for rheumatic disease with antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, and serum complement (C3, C4, CH50). Additional tests for FUO that may include throat culture, stool culture, tuberculin skin test with controls, HIV antibody, Epstein-Barr virus antibody profile, and B. henselae antibody. Consultation with infectious disease, immunology, rheumatic disease, or oncology specialists should be considered. Further tests may include lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid analysis and culture; computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the chest, abdomen, and head; radionuclide scans; and bone marrow biopsy for cytology and culture.