CHAPTER 113 Viral Hepatitis

CHAPTER 113 Viral Hepatitis

ETIOLOGY

There are six primary hepatotropic viruses:

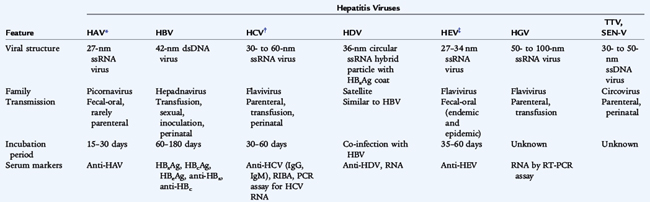

They differ in their virologic characteristics, transmission, severity, likelihood of persistence, and subsequent risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (Table 113-1). HDV, also known as the delta agent, is a defective virus that requires HBV for spread and causes either coinfection with HBV or superinfection in chronic HBsAg (hepatitis B surface antigen) carriers. HBV, HCV, and HDV infections can result in chronic hepatitis, or a chronic carrier state, which facilitates spread. The causes of 10% to 15% of cases of acute hepatitis are unknown.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

HAV causes approximately half of all cases of viral hepatitis in the United States. Among U.S. children, approximately 70% to 80% of all new cases of viral hepatitis are caused by HAV, 5% to 30% by HBV, and 5% to 15% by HCV. The major risk factors for HBV and HCV are injectable drug use, frequent exposure to blood products, and maternal infection. HEV occurs following travel to endemic areas outside the United States. HGV is prevalent in HIV-infected persons. HBV and HCV cause chronic infection, which may lead to cirrhosis and is a significant risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma and represents a persistent risk of transmission.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

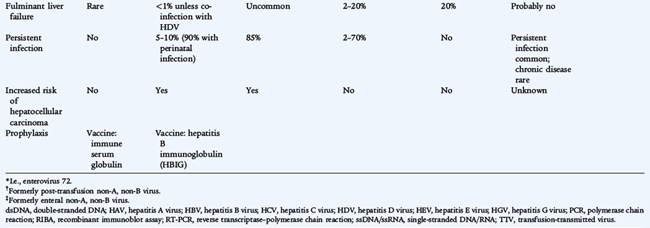

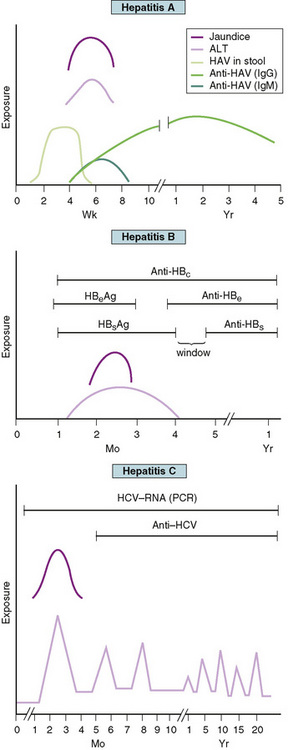

There is considerable overlap in the characteristic clinical courses of HAV, HBV, and HCV (Fig. 113-1). The preicteric phase, which lasts approximately 1 week, is characterized by headache, anorexia, malaise, abdominal discomfort, nausea, and vomiting and usually precedes the onset of clinically detectable disease. Infants with perinatal HBV may have immune complexes accompanied by urticaria and arthritis before the onset of icterus. Jaundice and tender hepatomegaly are the most common physical findings and are characteristic of the icteric phase. Prodromal symptoms, particularly in children, may abate during the icteric phase. Asymptomatic or mild, nonspecific illness without icterus is common with HAV, HBV, and HCV, especially in young children. Hepatitic enzymes may increase 15- to 20-fold. Resolution of the hyperbilirubinemia and normalization of the transaminases may take 6 to 8 weeks.

FIGURE 113-1 Clinical course and laboratory findings associated with hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HAV, hepatitis A virus; anti-HBc, antibody to hepatitis B core antigen; HBeAg, hepatitis B early antigen; anti-HBe, antibody to hepatitis B early antigen; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; anti-HBs, antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen; HCV, hepatitis C virus; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

LABORATORY AND IMAGING STUDIES

Alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase levels are elevated and generally reflect the degree of parenchymal inflammation. Alkaline phosphatase, 5α-nucleotidase, and total and direct (conjugated) bilirubin levels indicate the degree of cholestasis, which results from hepatocellular and bile duct damage. The prothrombin time is a good predictor of severe hepatocellular injury and progression to fulminant hepatic failure (see Chapter 130).

The diagnosis of viral hepatitis is confirmed by serologic testing (see Table 113-1 and Fig. 113-1). The presence of IgM-specific antibody to HAV with low or absent IgG antibody to HAV is presumptive evidence of HAV. There is no chronic carrier state of HAV. The presence of HBsAg signifies acute or chronic infection with HBV. Antigenemia appears early in the illness and is usually transient, but is characteristic of chronic infection. Maternal HBsAg status always should be determined when HBV infection is diagnosed in children younger than 1 year of age because of the likelihood of vertical transmission. Hepatitis B early antigen (HBeAg) appears in the serum with acute HBV. The continued presence of HBsAg and HBeAg in the absence of antibody to e antigen (anti-HBe) indicates high risk of transmissibility that is associated with ongoing viral replication. Clearance of HBsAg from the serum precedes a variable window period followed by the emergence of the antibody to surface antigen (anti-HBs), which indicates development of lifelong immunity and is also a marker of immunization. Antibody to core antigen (anti-HBc) is a useful marker for recognizing HBV infection during the window phase (when HBsAg has disappeared, but before the appearance of anti-HBs). Anti-HBe is useful in predicting a low degree of infectivity during the carrier state. Seroconversion after HCV infection may occur 6 months after infection. A positive result of HCV enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) should be confirmed with the more specific recombinant immunoblot assay, which detects antibodies to multiple HCV antigens. Detection of HCV RNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a sensitive marker for active infection, and results of this test may be positive 3 days after inoculation.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Many other viruses may cause hepatitis as part of systemic infection including Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), varicella zoster virus (VZV) (chickenpox), herpes simplex virus, and adenoviruses. Bacterial infections that may cause hepatitis include Escherichia coli sepsis and leptospirosis. Patients with cholecystitis, cholangitis, and choledocholithiasis may present with acute symptoms and jaundice. Other causes of acute liver disease in childhood include drugs (isoniazid, phenytoin, valproic acid, carbamazepine, oral contraceptives, acetaminophen), toxins (ethanol, poisonous mushroom), Wilson disease, metabolic disease (galactosemia, tyrosinemia), α1-antitrypsin deficiency, tumor, shock, anoxia, and graft-versus-host disease (see Chapter 130).

TREATMENT

The treatment of acute hepatitis is largely supportive and involves rest, hydration, and adequate dietary intake. Hospitalization is indicated for persons with severe vomiting and dehydration, a prolonged prothrombin time, or signs of hepatic encephalopathy. When the diagnosis of viral hepatitis is established, attention should be directed toward preventing its spread to close contacts. For HAV, hygienic measures include hand washing and careful disposal of excreta, contaminated diapers or clothing, needles, and other blood-contaminated items.

Chronic HBV infection may be treated with interferon alfa-2b or lamivudine, and HCV may be treated with interferon alfa alone or usually in combination with oral ribavirin. Most experience with these treatment regimens is in adults. The decision to treat is based on the patient’s current age, age at HBV acquisition, development of viral mutations during therapy, and stage of viral infection. Transmission of HBV by vertical transmission or infection early in life often results in chronic HBV infection in an immune tolerant phase, in which interferon usually is not effective.

COMPLICATIONS AND PROGNOSIS

A protracted or relapsing course may develop in 10% to 15% of cases of HAV in adults, lasting up to 6 months with an undulating course before eventual clinical resolution. Fulminant hepatitis with encephalopathy, gastrointestinal bleeding from esophageal varices or coagulopathy, and profound jaundice is uncommon, but is associated with a high mortality rate.

Most cases of acute viral hepatitis resolve without specific therapy, with less than 0.1% of cases progressing to fulminant hepatic necrosis. HAV and HEV cause only acute infection. HBV, HCV, and HDV may persist as chronic infection with chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and cirrhosis and the associated risk of hepatocellular carcinoma.

From 5% to 10% of adults with HBV develop persistent infection, defined by persistence of HBsAg in the blood for more than 6 months, compared with 90% of children who acquire HBV by perinatal transmission. Chronic HBsAg carriers are usually HBeAg-negative and have no clinical, biochemical, or serologic evidence of active hepatitis, unless there is superinfection with HDV. Approximately 10% to 15% of HBsAg carriers eventually clear HBsAg.

Approximately 85% of persons infected with HCV remain chronically infected, which is characterized by fluctuating transaminase levels (see Fig. 113-1). There is poor correlation of symptoms with ongoing liver damage. Approximately 20% of persons with chronic infection develop cirrhosis, and approximately 25% of those develop hepatocellular carcinoma. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and ethanol use increase the risk of HCV progression.

PREVENTION

Good hygienic practices significantly reduce the risk of fecal-oral transmission of HAV. Screening blood donors for evidence of hepatitis significantly reduces the risk of blood-borne transmission. Specific postexposure measures are recommended to prevent secondary cases in susceptible persons.

HAV vaccine is recommended for routine immunization of all children beginning at 12 months, and for unvaccinated older children in areas with targeted vaccination programs. Unvaccinated household and sexual contacts of persons with HAV should receive postexposure prophylaxis as soon as possible and within 2 weeks of the last exposure. A single dose of HAV vaccine at the age-appropriate dose is preferred for persons 12 months to 40 years of age. Immunoglobulin (0.02 mL/kg) given intramuscularly is preferred for children under 12 months of age, persons over 40 years of age, and immunocompromised persons. Unvaccinated travelers to endemic regions should receive a single dose of HAV vaccine administered at any time before departure.

HBV vaccine is recommended for routine immunization of all infants beginning at birth and for all children and adolescents through 18 years of age who have not been immunized previously (see Fig. 94-1). It also is recommended as a pre-exposure vaccination for older children and adults at increased risk of exposure to HBV including persons undergoing hemodialysis, recipients of clotting factor concentrates, residents and staff of institutions for developmentally disabled persons, men who have sex with men, injectable drug users, inmates of juvenile detention and other correctional facilities, and health care workers. HBV vaccine already has shown effectiveness in reducing the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in high-risk populations. Routine prenatal screening for HBsAg is recommended for all pregnant women in the United States. Infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers should receive HBV vaccine and hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) (0.5 mL) within 12 hours of birth, with subsequent vaccine doses at 1 month and 6 months of age followed by testing for HBsAg and anti-HBs at 9 to 15 months of age. Infants born to mothers whose HBsAg status is unknown should receive vaccine within 12 hours of birth. If maternal testing is positive for HBsAg, the infant should receive HBIG as soon as possible (no later than 1 week of age). The combination of HBIG and vaccination is 99% effective in preventing vertical transmission of HBV. Vaccination alone without HBIG may prevent 75% of cases of perinatal HBV transmission and approximately 95% of cases of symptomatic childhood HBV infection.

Postexposure prophylaxis of unvaccinated persons using HBIG and vaccine is recommended following needle stick injuries with blood from an HBsAg-positive patient and for household members with intimate contact, including sex partners.