CHAPTER 130 Liver Disease

CHAPTER 130 Liver Disease

CHOLESTASIS

Etiology and Epidemiology

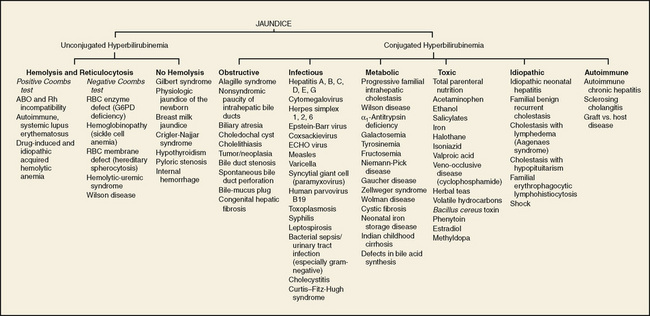

Cholestasis is defined as reduced bile flow and is characterized by elevation of the conjugated (direct) bilirubin fraction. This condition must be distinguished from ordinary neonatal jaundice, in which the direct bilirubin is never elevated (see Chapter 62). When direct bilirubin is elevated, many potentially serious disorders must be considered (Fig. 130-1). Emphasis must be placed on the rapid diagnosis of treatable disorders, especially biliary atresia and metabolic disorders such as galactosemia or tyrosinemia.

Clinical Manifestations

Cholestasis is caused by many different disorders, the common characteristic of which is cholestatic jaundice. Clinical features of several of the most common causes are given.

The jaundice of biliary atresia usually is not evident immediately at birth, but develops in the first 1 to 2 weeks of life. In this disorder, bile ducts are usually present at birth, but are then destroyed by an inflammatory process. Aside from jaundice, these infants do not initially appear ill. The liver injury progresses rapidly to cirrhosis; symptoms of portal hypertension with splenomegaly, ascites, muscle wasting, and poor weight gain are evident by a few months of age. If surgical drainage is not performed successfully early in the course (ideally by 2 months), progression to liver failure is inevitable.

Neonatal hepatitis is characterized by an ill-appearing infant with an enlarged liver and jaundice. There is no specific laboratory test, but if liver biopsy is performed, the presence of hepatocyte giant cells is characteristic. Hepatobiliary scintigraphy typically shows slow hepatic uptake with eventual excretion of isotope into the intestine. These infants have a good prognosis overall, with spontaneous resolution occurring in most.

α1-Antitrypsin deficiency presents with clinical findings indistinguishable from neonatal hepatitis. Only about 20% of all infants with the genetic defect exhibit neonatal cholestasis. Of these affected infants, about 30% go on to have severe chronic liver disease resulting in cirrhosis and liver failure. α1-Antitrypsin deficiency is the leading metabolic disorder requiring liver transplantation.

Alagille syndrome is characterized by chronic cholestasis with the unique liver biopsy finding of paucity of bile ducts in the portal triads. Associated abnormalities include peripheral pulmonary stenosis or other cardiac anomalies; hypertelorism; unusual facies with deep-set eyes, prominent forehead, and a pointed chin; butterfly vertebrae; and a defect of the ocular limbus (posterior embryotoxon). Cholestasis is variable but is usually lifelong and associated with hypercholesterolemia and severe pruritus. Progression to end-stage liver disease is uncommon.

Laboratory and Imaging Studies

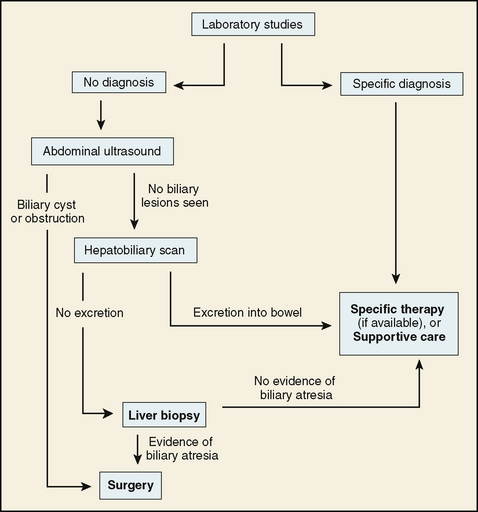

The laboratory approach to diagnosis of a neonate with cholestatic jaundice is presented in Table 130-1. Noninvasive studies are performed immediately. Imaging studies also are performed early to rule out biliary obstruction and other anatomic lesions that may be surgically treatable. When necessary to rule out biliary atresia or to obtain prognostic information, liver biopsy is a final option (Fig. 130-2).

TABLE 130-1 Laboratory and Imaging Evaluation of Neonatal Cholestasis

| Evaluation | Rationale |

|---|---|

| INITIAL TESTS | |

| Total and direct bilirubin | Elevated direct fraction confirms cholestasis |

| AST, ALT | Hepatocellular injury |

| GGT | Biliary obstruction/injury |

| RBC galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase | Galactosemia |

| α1-Antitrypsin level | α1-Antitrypsin deficiency |

| Urinalysis and urine culture | Urinary tract infection can cause cholestasis in neonates |

| Blood culture | Sepsis can cause cholestasis |

| Serum amino acids | Aminoacidopathies |

| Urine organic acids | Zellweger syndrome, lysosomal disorders |

| Sweat chloride or CF mutation analysis | Cystic fibrosis |

| Urine culture for cytomegalovirus | Congenital cytomegalovirus infection |

| INITIAL IMAGING STUDY | |

| Abdominal ultrasound | Choledochal cyst, gallstones, mass lesion, Caroli disease |

| SECONDARY IMAGING STUDY | |

| Hepatobiliary scintigraphy | Rule out biliary atresia |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CF, cystic fibrosis; GGT, γ-glutamyltransferase; RBC, red blood cell.

Treatment

Treatment of extrahepatic biliary atresia is the surgical Kasai procedure. The damaged bile duct remnant is removed and replaced with a roux-en-Y loop of jejunum. This operation must be performed before 2 to 3 months of age to have the best chance of success. Even so, the success rate is low; many children eventually require liver transplantation. Some metabolic causes of neonatal cholestasis are treatable by dietary manipulation (galactosemia) or medication (tyrosinemia); all affected patients require supportive care. This includes fat-soluble vitamin supplements (vitamins A, D, E, and K) and formula containing medium-chain triglycerides, which can be absorbed without bile salt–induced micelles. Choleretic agents, such as ursodeoxycholic acid and phenobarbital, may improve bile flow in some conditions.

FULMINANT LIVER FAILURE

Etiology and Epidemiology

Fulminant liver failure is defined as severe liver disease with onset of hepatic encephalopathy within 8 weeks after initial symptoms, in the absence of chronic liver disease. Etiology includes viral hepatitis, metabolic disorders, ischemia, neoplastic disease, and toxins (Table 130-2).

Clinical Manifestations

Liver failure is a multisystem disorder with complex interactions among the liver, kidneys, vascular structures, gut, central nervous system (CNS), and immune function. Hepatic encephalopathy is characterized by varying degrees of impairment (Table 130-3). Respiratory compromise occurs as severity of the failure increases and requires early institution of ventilatory support. Hypoglycemia resulting from impaired glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis must be prevented. Renal function is impaired, and frank renal failure, or hepatorenal syndrome, may occur. This syndrome is characterized by low urine output, azotemia, and low urine sodium content. Ascites develops secondary to hypoalbuminemia and disordered regulation of fluid and electrolyte homeostasis. Increased risk of infection occurs and may cause death. Portal hypertension causes an enlarged spleen with thrombocytopenia, aggravating the risk of hemorrhage from esophageal varices.

Laboratory and Imaging Studies

Laboratory studies are used to follow the severity of the liver injury and to monitor the response to therapy. Coagulation tests and serum albumin are used to monitor hepatic synthetic function but are confounded by administration of blood products and clotting factors. Vitamin K should be administered to maximize the liver’s ability to synthesize factors II, VII, IX, and X. In addition to monitoring prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time, many centers measure factor V serially as a sensitive index of synthetic function. Renal function tests, electrolytes, serum ammonia, blood counts, and urinalysis also should be followed. In the setting of acute liver failure, liver biopsy may be indicated to ascertain the nature and degree of injury and estimate the likelihood of recovery. In the presence of coagulopathy, biopsy must be done using a transjugular or surgical approach.

Treatment

Because of the life-threatening and complex nature of this condition, management must be carried out in an intensive care unit (ICU) at a liver transplant center. Treatment of acute liver failure is supportive; the definitive lifesaving therapy is liver transplantation. Supportive measures are listed in Table 130-4. Efforts are made to treat metabolic derangements, avoid hypoglycemia, support respiration, minimize hepatic encephalopathy, and support renal function.

TABLE 130-4 Treatment of Fulminant Liver Failure

| Problem | Management |

|---|---|

| Hepatic encephalopathy | |

| Coagulopathy | |

| Hypoglycemia | Intravenous glucose supplied with ≥10% dextrose solution, electrolytes as appropriate |

| Ascites | |

| Renal failure |

CHRONIC LIVER DISEASE

Etiology and Epidemiology

Chronic liver disease in childhood is characterized by the development of cirrhosis and its complications and by progressive hepatic failure. Causative conditions may be congenital or acquired. Major congenital disorders leading to chronic disease include biliary atresia, tyrosinemia, untreated galactosemia, and α1-antitrypsin deficiency. In older children, hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), autoimmune hepatitis, Wilson disease, primary sclerosing cholangitis, cystic fibrosis, and biliary obstruction secondary to choledochal cyst are leading causes.

Clinical Manifestations

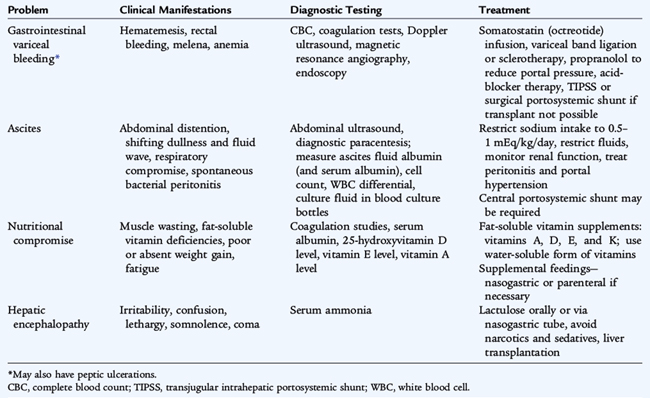

Chronic liver disease is characterized by the consequences of portal hypertension, impaired hepatocellular function, and cholestasis. Portal hypertension caused by cirrhosis results in risk of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, ascites, and reduced hepatic blood flow. Blood entering the portal vein from the splenic and mesenteric veins is diverted to collateral circulation that bypasses the liver, enlarging these previously tiny vessels in the esophagus, stomach, and abdomen. Esophageal varices are particularly prone to bleed, but bleeding also can occur from hemorrhoidal veins, congested gastric mucosa, and gastric varices. Ascites develops as a result of weeping from pressurized visceral veins and from excessive renal water and salt retention. Ascitic fluid often becomes quite massive, interfering with patient comfort and respiration, and is easily infected (spontaneous bacterial peritonitis). The spleen enlarges secondary to impaired splenic vein outflow, causing excessive scavenging of platelets and white blood cells (WBCs); decreased cell counts increase the patient’s susceptibility to bleeding and infection.

Impaired hepatocellular function is associated with coagulopathy unresponsive to vitamin K, low serum albumin, elevated ammonia, and hepatic encephalopathy. The diversion of portal blood away from the liver via collateral circulation worsens this process. Malaise develops and contributes to poor nutrition, leading to muscle wasting and other consequences.

Chronic cholestasis causes debilitating pruritus and deepening jaundice. The reduced excretion of bile acids impairs absorption of fat and fat-soluble vitamins. Deficiency of vitamin K impairs production of clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X and increases the risk of bleeding. Vitamin E deficiency leads to hematologic and neurologic consequences unless corrected.

Laboratory and Imaging Studies

Laboratory studies include specific tests for diagnosis of the underlying illness and testing to monitor the status of the patient. Children presenting for the first time with evidence of chronic liver disease should have a standard investigation (Table 130-5). Monitoring should include coagulation tests, electrolytes and renal function testing, complete blood count with platelet count, transaminases, alkaline phosphatase, and γ-glutamyltransferase at appropriate intervals. Frequency of testing should be tailored to the pace of the patient’s illness. Ascites fluid can be tested for infection by culture and cell count and generally is found to have an albumin concentration lower than that of serum, with a serum-ascites albumen gradient (SAAG) greater than 1.1 g/dL.

TABLE 130-5 Laboratory and Imaging Investigation of Chronic Liver Disease

METABOLIC TESTING

VIRAL HEPATITIS

AUTOIMMUNE HEPATITIS

TESTS TO EVALUATE LIVER FUNCTION AND INJURY

ANATOMIC EVALUATION

TESTS TO EVALUATE NUTRITIONAL STATUS

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CBC, complete blood count; CF, cystic fibrosis; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; GGT, γ-glutamyltransferase; HBeAg, hepatitis B early antigen; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen.

* Perform when indicated to obtain specific anatomic information.

Treatment

Treatment of chronic liver disease is complex. Supportive care for each of the many problems encountered in these patients is outlined in Table 130-6. Ultimately, survival depends on the availability of a donor liver and the patient’s candidacy for transplantation. When transplantation is not possible or is delayed, portal hypertension can be treated by a portosystemic shunt. The transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) consists of an expandable stent placed between the hepatic vein and a branch of the portal vein within the hepatic parenchyma. This procedure is performed using catheters inserted via the jugular vein and is entirely nonsurgical. All portosystemic shunts carry increased risk of hepatic encephalopathy.

SELECTED CHRONIC HEPATIC DISORDERS

Wilson Disease

Wilson disease is characterized by abnormal storage of copper in the liver, leading to hepatocellular injury, CNS dysfunction, and hemolytic anemia. It is an autosomal recessive trait caused by mutations in the ATP7B gene, which codes for an ATP-driven copper pump. The diagnosis is made by identifying depressed serum levels of ceruloplasmin, elevated 24-hour urine copper excretion, the presence of Kayser-Fleischer rings in the iris, evidence of hemolysis, and elevated hepatic copper content. In any single patient, one or more of these measures may be normal. Clinical presentation also varies, but seldom occurs before age 3 years. Neurologic abnormalities may predominate, including tremor, decline in school performance, worsening handwriting, and psychiatric disturbances. Anemia may be the first noted symptom. Hepatic presentations include appearance of jaundice, spider hemangiomas, portal hypertension, and fulminant hepatic failure. Treatment consists of administration of copper chelating drugs (penicillamine or trientine), monitoring of urine copper excretion at intervals. Zinc salts inhibit intestinal copper absorption and are increasingly being used, especially after initial chelation therapy has reduced the excessive body copper stores. Adequate therapy must be continued for life to prevent liver and CNS deterioration.

Autoimmune Hepatitis

Immune-mediated liver injury may be primary or occur in association with other autoimmune disorders, such as inflammatory bowel disease or systemic lupus erythematosus. Diagnosis is made on the basis of elevated serum total IgG and the presence of an autoantibody, most commonly antinuclear, anti–smooth muscle, or anti–liver-kidney microsomal antibody. Liver biopsy reveals a plasma cell–rich portal infiltrate with piecemeal necrosis. Treatment consists of corticosteroids initially, usually with the addition of an immunosuppressive drug after remission is achieved. Steroids are tapered gradually as tolerated to minimize glucocorticoid side effects. Many patients require lifelong immunosuppressive therapy, but some may be able to stop medications after several years under careful monitoring for recurrence.

Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis

Primary sclerosing cholangitis typically occurs in association with ulcerative colitis. It may be accompanied by evidence of autoimmune hepatitis; this is termed overlap syndrome. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (p-ANCA) is present in most cases. Diagnosis is by liver biopsy and cholangiography, generally performed as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or noninvasively by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Treatment consists of ursodiol administration, which seems to slow progression and improves indices of hepatic injury; dilation of major biliary strictures during ERCP; and liver transplantation for end-stage liver disease.

Steatohepatitis

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease or nonalcoholic fatty hepatitis is characterized by the presence of macrovesicular fatty change in hepatocytes on biopsy. Varying degrees of inflammation and portal fibrosis may be present. This disorder occurs in obese children, sometimes in association with insulin-resistant (type 2) diabetes and hyperlipidemia. Children with marked obesity, with or without type 2 diabetes, who have elevated liver enzymes and no other identifiable liver disease, are likely to have this condition. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease can progress to significant fibrosis. Treatment is with diet and exercise. Vitamin E may have some benefit. Efforts should be made to control blood glucose and hyperlipidemia and promote weight loss. In general, the rate of progression to end-stage liver disease is slow.